Introduction

The inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) is among the most frequently used regional anesthetic techniques in dental practice. This technique is routinely performed to achieve mandibular anesthesia for various surgical and restorative procedures. This technique involves the targeted deposition of a local anesthetic solution in the vicinity of the mandibular foramen, where the inferior alveolar nerve enters the mandibular canal.[1] Effective administration depends greatly on accurate localization of anatomical landmarks to ensure effective nerve blockade.

A critical anatomical consideration in this region is the pterygoid venous plexus, located posterior and superior to the mandibular foramen, which must be avoided to reduce the risk of hematoma or inadvertent vascular injection. Despite its frequent use, the IANB has a relatively high failure rate—estimated at 15% to 20%—primarily due to inaccurate identification of anatomical landmarks rather than anatomical anomalies.[2] Nevertheless, the procedure is generally well tolerated, with major complications being rare.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Branches of the Mandibular Nerve

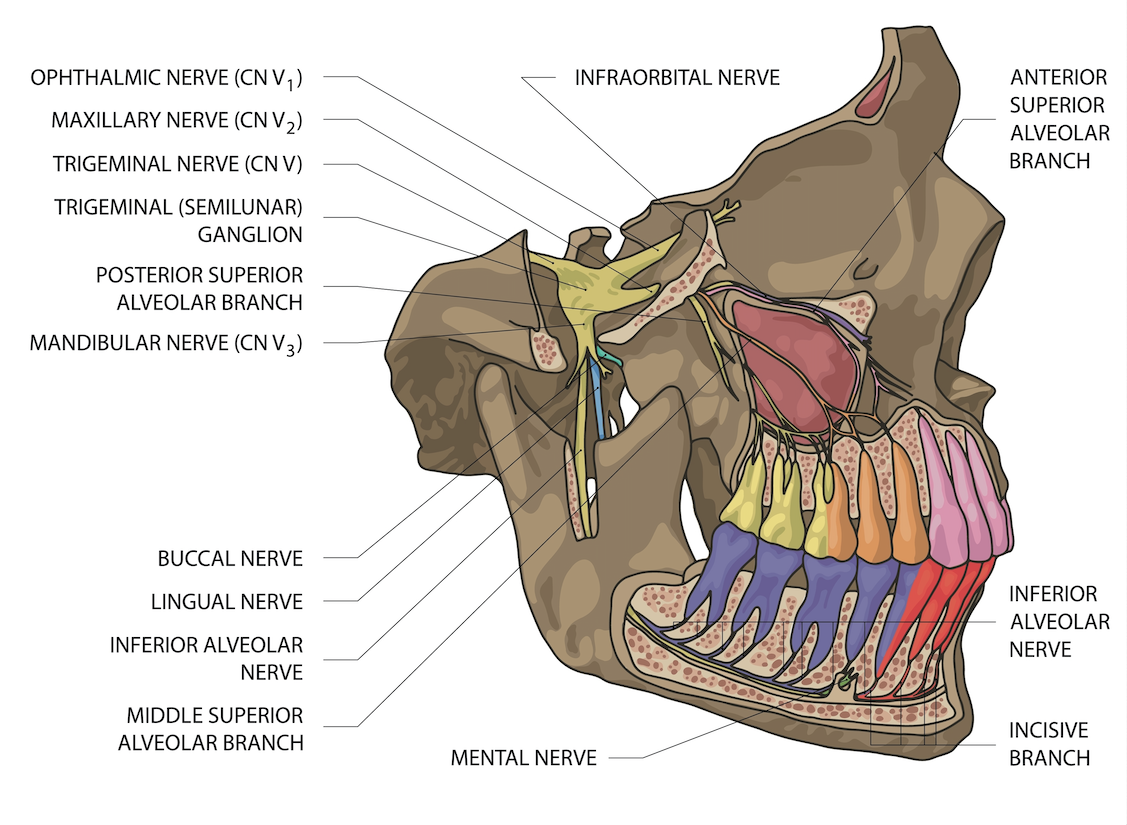

The mandibular nerve is the third division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V, division V3). The mandibular nerve exits the skull via the foramen ovale at the base of the cranium and then divides into anterior and posterior branches (see Image. Innervation of the Dentition by Maxillary and Mandibular Nerves). The main trunk of the mandibular nerve gives off a branch that innervates the medial pterygoid muscle and a meningeal branch known as nervus spinosus.

The anterior division of the mandibular nerve primarily consists of motor fibers that innervate the temporalis, lateral pterygoid, and masseter muscles. A sensory branch, the long buccal nerve, also arises from the anterior division. The posterior division is primarily sensory, giving rise to the auriculotemporal, lingual, and inferior alveolar nerves. Before entering the mandibular foramen, the inferior alveolar nerve gives off a branch to the mylohyoid muscle. The nerve then enters the inferior alveolar canal and terminates into 2 branches—the incisive and mental nerves.[1]

Location of Mandibular Foramen

For an effective IANB, the local anesthetic solution must be deposited near the nerve before it enters the mandibular foramen. Several studies have indicated that depositing the local anesthetic molecules into the pterygomandibular space can achieve the desired anesthesia.[3]

Literature indicates that the position of the mandibular foramen can vary, and it is not always located midway along the anteroposterior dimension of the mandibular ramus. On average, the foramen lies approximately 2.75 mm posterior to the midpoint of the mandibular ramus. The distance between the mandibular foramen and the coronoid notch is estimated to be about 19 mm. The foramen may be positioned either at the level of or below the occlusal plane. The location of the mandibular foramen is relative to the occlusal plane, and it also varies with age. The mandibular foramen is located below the occlusal plane level in adults, whereas it is found at or below the occlusal plane level in children.[4]

Indications

The IANB is indicated for procedures requiring profound anesthesia of the mandibular teeth and associated soft tissues. IANB is routinely used in various surgical and restorative interventions involving the mandible, including, but not limited to, dental extractions, periodontal surgeries, implant placement, endodontic treatment, management of trauma and fractures, and complex restorative procedures.[5]

Beyond its role in conventional dentistry, the IANB is also utilized in maxillofacial surgical settings, particularly when regional anesthesia is preferred over general anesthesia. The block provides sensory anesthesia to the ipsilateral mandibular teeth, the body of the mandible, the lower lip, and part of the buccal and lingual soft tissues. The extent of anesthesia may vary depending on whether supplementary nerve blocks, such as the long buccal or lingual nerve blocks, are administered concurrently.

Proper patient selection and a thorough understanding of anatomical and procedural considerations are essential for achieving optimal outcomes and minimizing the risk of complications. Indications should be carefully assessed in the context of patient-specific anatomy, medical history, and procedural requirements.

Contraindications

Although the IANB is a widely utilized and generally safe anesthetic technique, certain contraindications must be considered to ensure patient safety and procedural success. These may be classified as absolute or relative.

Absolute Contraindications

-

Documented allergy to local anesthetic agents: Hypersensitivity to amide- or ester-type anesthetics contraindicates the use of standard formulations unless suitable alternatives are available and medically approved.

-

Infection or inflammation at the injection site: The presence of localized infection, cellulitis, or abscess in the pterygomandibular space increases the risk of spreading infection and may reduce anesthetic efficacy due to altered tissue pH.[6]

Relative Contraindications

-

Bleeding disorders or anticoagulant therapy: Although not an absolute contraindication, patients with coagulopathies or those receiving anticoagulant medications have an increased risk of hematoma formation, particularly due to the proximity of the pterygoid venous plexus.

-

Severe trismus or limited mandibular opening: Restricted access to the injection site may hinder accurate needle placement, increasing the risk of technical failure or iatrogenic injury.

-

Psychological or behavioral conditions (eg, severe dental anxiety and uncooperative pediatric patients): Such cases may require alternative approaches, including sedation or general anesthesia, to ensure patient safety and cooperation during the procedure.

-

Neurological disorders involving the mandibular nerve: Preexisting conditions such as trigeminal neuralgia or prior nerve injury require careful risk-benefit evaluation and consideration of alternative anesthetic strategies when appropriate.

A comprehensive medical and dental history, along with a thorough intraoral and extraoral examination, is essential for identifying potential contraindications and appropriately adjusting the anesthetic plan.

Equipment

Effective and safe administration of the IANB requires using standardized, sterile, and ergonomically appropriate equipment. Proper selection of materials enhances both anesthetic efficacy and patient comfort.

Syringe

-

A standard metal aspirating dental syringe is recommended, as it allows for controlled delivery of the anesthetic and enables both positive and negative aspiration, reducing the risk of inadvertent intravascular injection.

-

Self-aspirating syringes may also improve ease of use and reduce operator fatigue.

Needle

-

A long needle, typically 25- or 27-gauge and approximately 32 mm long, is preferred for reaching the target depth near the mandibular foramen.

-

A 25-gauge needle is often favored for its improved rigidity and reduced risk of deflection, which enhances precision during deep tissue penetration.

- In patients with smaller mandibular anatomy or in pediatric cases, a 27-gauge long needle may be preferable to accommodate anatomical constraints while still providing sufficient length to reach the target site near the mandibular foramen.

-

Single-use, presterilized needles should be used to prevent cross-contamination.

Local Anesthetic Cartridge

-

Standard 1.8 mL dental cartridges containing an amide-type local anesthetic (eg, 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine) are commonly used.

-

The choice of anesthetic agent and vasoconstrictor concentration depends on the procedure’s duration, the patient’s medical history, and specific surgical requirements.

Topical Anesthetic

-

A topical anesthetic gel or spray (commonly 20% benzocaine) is applied to the mucosal insertion site 1 to 2 minutes before needle penetration to minimize discomfort and facilitate smooth needle entry.

Protective and Ancillary Materials

-

Cotton gauze is used to dry the mucosa before applying the topical anesthetic.

-

Disposable gloves, masks, and eye protection are worn to ensure adherence to infection control protocols.

-

A mirror and explorer can assist with tissue retraction and identification of anatomical landmarks.

-

A sharps container is required to safely dispose of used needles and cartridges after injection.

Proper equipment inspection before use ensures functionality, sterility, and safety. Additionally, all materials must be prepared using aseptic techniques to prevent contamination and iatrogenic infection.

Personnel

The successful administration of an IANB requires the involvement of trained dental professionals who possess comprehensive knowledge of regional anatomy, anesthetic pharmacology, and procedural techniques. The roles and qualifications of personnel may vary based on the clinical setting and regional regulatory frameworks, but typically include:

Dentist or Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon

-

The primary operator should be a licensed dental practitioner with formal training in local anesthesia techniques, including general dentists, pediatric dentists, and oral and maxillofacial surgeons.

-

Competency must extend beyond the technical execution of the IANB to include the ability to recognize and manage potential complications such as hematoma, nerve injury, and systemic toxicity.

Dental Hygienist (Where Permitted by Jurisdiction)

-

In certain regions, licensed dental hygienists with additional certification may be authorized to administer local anesthesia, including the IANB, under a dentist's direct or indirect supervision.

-

Their training must include both didactic and clinical components covering head and neck anatomy, injection techniques, and medical emergency protocols.

Dental Assistant

-

The dental assistant plays a vital supportive role by preparing equipment, assisting with patient positioning, maintaining aseptic technique, and monitoring patient comfort throughout the procedure.

-

Although not responsible for administering anesthesia, the assistant’s efficiency and attentiveness significantly contribute to procedural success and patient safety.

Emergency Support Personnel (as Needed)

-

In settings involving advanced sedation or medically compromised patients, personnel trained in Basic Life Support (BLS) or Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) must be available to manage rare but potentially life-threatening complications, such as anaphylaxis or local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST).

Preparation

The operator should stand on the side opposite the injection site. The patient is positioned in a semi-inclined posture, with the head stabilized against the chair’s headrest and the mouth fully open to allow clear visualization of anatomical landmarks and needle insertion. A topical anesthetic, such as 20% benzocaine, can be applied to the target area to reduce pain and discomfort during injection.[1] The area must be dried with gauze before application to increase the penetration of the topical anesthesia solution into the mucosa.

Technique or Treatment

Conventional Technique

The conventional IANB technique is the most commonly used approach. Accurate identification of key anatomical landmarks is essential, including the coronoid process, coronoid notch, anterior and posterior borders of the mandibular ramus, and the sigmoid notch. Additional important landmarks include the pterygomandibular raphe—formed by the buccinator and superior constrictor muscles—and the coronoid notch, with the ideal needle insertion point located between these 2 structures.

The syringe barrel is positioned over the premolars on the side opposite the injection. The insertion point lies along an imaginary line extending from the deepest part of the pterygomandibular raphe to the coronoid notch. The exact location of the entry point is one-fourth the distance toward the raphe above the occlusal level of mandibular teeth.

The needle is inserted after locating the target area until bony resistance is felt, typically at a depth of 19 to 25 mm. The needle is then gently and slowly withdrawn. If the needle can be advanced beyond 25 mm, it may be positioned posterior to the posterior border of the mandible. Conversely, premature contact with bone indicates an anterior needle placement.[7]

Modifications to the Conventional Technique

Various modifications or alternatives to the conventional IANB technique have been reported.

- Thangavelu et al proposed using the internal oblique ridge as the primary anatomical landmark. In this method, the thumb is placed on the retromolar area, with the tip indicating the internal oblique ridge. The insertion point is located 2 mm posterior to the internal oblique ridge and 6 to 8 mm above the midpoint of the thumb. The syringe barrel is positioned over the opposite premolars, and the needle is advanced until it contacts bone. This technique has demonstrated a success rate of approximately 95%.[8]

- Boonsiriseth et al used a 30-mm long needle with an insertion point similar to the conventional IANB technique. However, unlike the conventional method, where the syringe barrel is positioned on the opposite side, they placed the syringe barrel at the occlusal level of the ipsilateral teeth.[9]

- Suazo Galdames et al advocated for the IANB using the retromolar triangle approach, which involves depositing the anesthetic at the retromolar triangle. This area contains bone perforated by holes of varying sizes, allowing passage of the buccal artery that anastomoses with the inferior alveolar vessels within the mandibular canal. Anesthesia administered in this area can reach the inferior alveolar nerve through communications between the mandibular canal and the retromolar triangle. This technique has a success rate of 72% and may be particularly valuable in patients with blood disorders where the conventional IANB is challenging.[7]

- Other available techniques primarily target branches of the mandibular nerve rather than the inferior alveolar nerve. These include the Gow-Gates technique, the Vazirani-Akinosi (closed-mouth) technique, and the Fischer 3-stage technique.[10]

Computer-Controlled Local Anesthetic Delivery

Computer-controlled local anesthetic delivery (CCLAD) system is an automated device that minimizes injection pain by delivering a slow, continuous flow of anesthetic solution. Single-use, disposable, lightweight handpieces are commonly used, especially for anesthesia of the attached gingiva, hard palate, and periodontal ligament. Additionally, these devices can enhance the precision of anesthetic delivery for deeper tissue blocks such as the IANB.[8]

The integration of CCLAD systems represents a significant advancement in the administration of regional anesthesia, including the IANB. These devices are designed to enhance precision, control, and patient comfort by using microprocessor-guided feedback to regulate the rate and pressure of anesthetic administration.[11]

Mechanism of Action

CCLAD systems deliver local anesthetic at a consistent, slow rate, reducing the discomfort associated with rapid infiltration and high-pressure injections. These devices offer visual and auditory feedback to guide the operator throughout the injection process, thereby promoting accurate placement and minimizing variability between operators.

Advantages of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block Administration

-

Improved patient comfort: CCLAD minimizes pain associated with tissue distention and high-pressure delivery, thereby reducing patient anxiety and enhancing the overall experience, particularly in pediatric and phobic populations.[11][12]

-

Enhanced precision: The ergonomic design and steady delivery rate of CCLAD systems facilitate more controlled needle advancement and anesthetic deposition near the mandibular foramen, potentially improving the block's success rate.

-

Reduced injection force: The system minimizes the physical effort required for manual injection, which can be especially beneficial in patients with dense soft tissue or complex anatomical conditions.[11]

Clinical Considerations

Although CCLAD devices offer several potential benefits, successful use in the IANB technique still demands a thorough understanding of anatomy and injection landmarks. Furthermore, factors such as cost, equipment familiarity, and clinical time constraints may limit their widespread adoption. Proper training is essential to ensure seamless integration of the technology into existing clinical workflows without compromising procedural efficiency.

Limitations and Evidence

Although CCLAD has demonstrated favorable outcomes in reducing patient-reported pain and improving operator control, current evidence remains mixed regarding its ability to significantly enhance the success rate of IANBs compared to conventional techniques. Further randomized controlled trials are needed to establish its definitive efficacy and cost-effectiveness in routine dental practice.[13][9]

Complications

Although the IANB is a routinely performed and generally safe procedure, it carries inherent risks. Complications can result from technical errors, anatomical variations, or adverse patient reactions. These complications may be classified as local, systemic, or neurological, and they can range from mild, transient effects to rare but serious events.

Local Complications

-

Hematoma formation: Accidental injury to the pterygoid venous plexus or inferior alveolar artery may lead to hematoma formation, typically presenting as swelling, bruising, and mild discomfort. Proper aspiration and slow injection help minimize this risk.[14]

-

Trismus: Limited mandibular opening may develop due to trauma or inflammation of the medial pterygoid muscle or surrounding tissues. Although often self-limiting, persistent cases may require anti-inflammatory treatment and physical therapy.

-

Needle breakage: Although rare with modern single-use needles, breakage can occur, particularly if the needle is inserted up to the hub or if the patient moves suddenly during injection. Retrieval may require surgical intervention.

-

Pain during injection: Pain can result from rapid deposition, contact with the periosteum, or excessive tissue distention. Proper technique and topical anesthetics can help minimize discomfort.

-

Soft tissue injury: Postoperative biting of the lip, cheek, or tongue can occur due to residual anesthesia, especially in pediatric or special needs patients. Educating caregivers is essential to prevent self-inflicted trauma.

Neurological Complications

-

Transient or permanent nerve injury can occur from direct trauma or intraneural injection, leading to paresthesia, dysesthesia, or anesthesia affecting the lower lip, tongue, or mandibular teeth. Most cases resolve spontaneously within weeks to months, though rare instances may result in permanent deficits.[15][16][17]

-

Facial Nerve Paralysis: Inadvertent deposition of anesthetic into the parotid gland capsule, due to overly posterior or deep needle placement, may cause transient facial nerve paralysis. This can manifest as an inability to close the eyelid or asymmetrical facial expression. Symptoms typically resolve within hours as the anesthetic effect.[15][18][19][20]

Systemic Complications

-

Intravascular injection and systemic toxicity: Accidental intravascular injection, administered especially into the inferior alveolar artery or adjacent venous plexus, can cause symptoms ranging from dizziness and palpitations to severe complications like seizures or cardiovascular collapse. Performing aspiration before injection is essential to minimize this risk.

-

Allergic reactions: Although rare with modern amide-type anesthetics, allergic reactions may occur, particularly in response to preservatives or sulfite-containing vasoconstrictors. These reactions can range from localized urticaria to severe anaphylaxis, requiring prompt emergency management.

-

Infection: While rare, breaches in aseptic technique or injection through infected tissue can introduce pathogens, resulting in localized or systemic infections. Strict adherence to sterilization protocols and avoiding injections into inflamed areas are crucial preventive measures.

Proper technique, thorough anatomical knowledge, careful patient assessment, and strict adherence to infection control protocols are essential for minimizing complications. Early recognition and timely management are critical to ensuring optimal patient outcomes.

Clinical Significance

The IANB is a regional anesthesia technique widely used in dental and maxillofacial practice to achieve mandibular anesthesia. The effectiveness, versatility, and broad applicability of IANB in both surgical and restorative procedures establish it as a cornerstone of modern dental anesthesia.

Widespread Application in Clinical Practice

The IANB is indispensable for performing a wide array of intraoral procedures involving mandibular structures, including:

- Exodontia of posterior mandibular teeth

- Surgical exposure of impacted third molars

- Restorative interventions and endodontic treatment of mandibular molars and premolars

- Periodontal surgery and crown lengthening in the posterior mandible

- Implant surgery

As the inferior alveolar nerve innervates the mandibular teeth and their supporting structures, achieving adequate anesthesia in this region is essential for ensuring pain control and procedural efficiency.

Foundation of Mandibular Anesthesia

As a fundamental technique, the IANB serves as the primary method for mandibular nerve anesthesia. Mastery of this block is essential to the clinical competency of dental professionals. This also provides the foundation for more advanced mandibular techniques, such as the Gow-Gates or Vazirani-Akinosi nerve blocks, especially when conventional methods prove inadequate.

Implications for Patient Comfort and Safety

Effective administration of the IANB improves patient comfort, reduces the need for supplemental injections, and minimizes procedural interruptions due to inadequate anesthesia. Conversely, improper execution can result in significant patient distress, procedural delays, and an increased risk of complications, underscoring the importance of anatomical proficiency and technical skill.

Training and Standard of Care

Given its ubiquity in dental education and its status as a standard clinical technique, proficiency in the IANB is widely regarded as a benchmark of competence for students and clinicians. Furthermore, in many jurisdictions, licensure examinations and clinical competency assessments include the IANB as a core requirement.

Clinical Decision-Making and Technique Selection

The IANB holds important clinical relevance, particularly when considering patient-specific factors. Alternative techniques may be more appropriate in patients with coagulation disorders, active infections at the injection site, or anatomical variations. Therefore, the decision to use an IANB demands careful judgment based on the patient’s medical history and the requirements of the procedure.

In summary, the IANB is more than a routine injection; it is a critical procedure with significant implications for delivering effective, safe, and patient-centered dental care.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although the administration of the IANB primarily falls within the scope of dental professionals, such as general dentists, oral surgeons, and dental anesthesiologists, the procedure often occurs within broader healthcare settings. In these environments, interprofessional collaboration among healthcare teams enhances patient safety, optimizes outcomes, and ensures continuity of care. The involvement of physicians, nurses, and allied healthcare personnel is significant in complex cases or institutional settings.

Physicians

Although physicians are not usually involved in the technical administration of the IANB, their role is crucial in cases involving:

-

Systemic medical conditions: Physicians assist in evaluating patients with bleeding disorders, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or immunocompromise to determine whether modifications to anesthetic techniques or agents are warranted.

-

Preoperative clearance and medication management: Physicians guide perioperative planning, including decisions about anticoagulant therapy, corticosteroid use, and management of comorbidities that may affect anesthesia safety.

-

Emergency response and consultation: In rare cases of systemic complications, such as LAST, allergic reactions, or vasovagal syncope, physicians play a crucial role in medical stabilization and follow-up care.

- Emergency department physicians: Emergency physicians may use the IANB to provide rapid, targeted pain relief for patients presenting with acute mandibular trauma, dental abscesses, or severe odontogenic infections. In these situations, the IANB serves as an effective regional anesthetic technique that minimizes reliance on systemic opioids and facilitates procedures such as incision and drainage or dental stabilization. Physicians must be familiar with the anatomical landmarks and potential complications associated with the block to ensure safe and effective pain management in the fast-paced emergency room setting.

Nurses

Nurses play a crucial, supportive, and educational role, especially in oral surgery centers, hospital-based dentistry, and community clinics, as mentioned below.

-

Preoperative assessment: Before the procedure, nurses collect vital signs, review medical histories, and ensure that informed consent documentation is complete.

-

Intraoperative support: During the IANB, nurses assist with patient positioning, monitor for adverse reactions, and provide emotional reassurance to help reduce anxiety-related complications.

-

Postoperative monitoring and discharge education: Nurses are essential in identifying early signs of complications such as hematoma, trismus, or paresthesia, and in educating patients on postoperative care, such as avoiding trauma to anesthetized areas and recognizing signs of infection.

Pharmacists

-

Medication safety and dosage management: Pharmacists play a crucial role by reviewing drug interactions and contraindications related to local anesthetics and vasoconstrictors. They also advise on dosage adjustments for patients with hepatic or renal impairment.

- Anesthetic agent selection and adjunctive medication management: Pharmacists provide guidance on selecting anesthetic agents, particularly when multiple agents or adjunctive medications are involved.

Dental Assistants and Hygienists

Dental assistants play a vital operational role by preparing anesthetic equipment, maintaining aseptic technique, and helping to ensure a calm and safe procedural environment. In some jurisdictions, dental hygienists trained in local anesthesia may be authorized to perform IANBs under supervision, thereby expanding access to anesthesia services in community and public health settings.

Emergency Medical Personnel

In surgical centers or rural clinics with limited advanced medical support, trained emergency medical personnel are critical in responding to acute adverse events, such as anaphylaxis or seizures, following an IANB. Their preparedness to promptly implement emergency protocols, including airway management and administration of epinephrine or anticonvulsants, is essential to ensuring patient safety.

Effective collaboration among dentists, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals is crucial for the safe and successful administration of the IANB, especially in medically complex patients or institutional settings. Interprofessional coordination enhances perioperative risk assessment, improves patient education, facilitates timely management of complications, and ensures the delivery of high-quality, patient-centered dental care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Khalil H. A basic review on the inferior alveolar nerve block techniques. Anesthesia, essays and researches. 2014 Jan-Apr:8(1):3-8. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.128891. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25886095]

AlHindi M, Rashed B, AlOtaibi N. Failure rate of inferior alveolar nerve block among dental students and interns. Saudi medical journal. 2016 Jan:37(1):84-9. doi: 10.15537/smj.2016.1.13278. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26739980]

Takasugi Y, Furuya H, Moriya K, Okamoto Y. Clinical evaluation of inferior alveolar nerve block by injection into the pterygomandibular space anterior to the mandibular foramen. Anesthesia progress. 2000 Winter:47(4):125-9 [PubMed PMID: 11432177]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHolliday R, Jackson I. Superior position of the mandibular foramen and the necessary alterations in the local anaesthetic technique: a case report. British dental journal. 2011 Mar 12:210(5):207-11. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.145. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21394145]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThangavelu K, Kannan R, Kumar NS, Rethish E, Sabitha S, Sayeeganesh N. Significance of localization of mandibular foramen in an inferior alveolar nerve block. Journal of natural science, biology, and medicine. 2012 Jul:3(2):156-60. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.101896. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23225978]

Ueno T, Tsuchiya H, Mizogami M, Takakura K. Local anesthetic failure associated with inflammation: verification of the acidosis mechanism and the hypothetic participation of inflammatory peroxynitrite. Journal of inflammation research. 2008:1():41-8 [PubMed PMID: 22096346]

Suazo Galdames IC, Cantín López MG, Zavando Matamala DA. Inferior alveolar nerve block anesthesia via the retromolar triangle, an alternative for patients with blood dyscrasias. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal. 2008 Jan 1:13(1):E43-7 [PubMed PMID: 18167480]

Kim C, Hwang KG, Park CJ. Local anesthesia for mandibular third molar extraction. Journal of dental anesthesia and pain medicine. 2018 Oct:18(5):287-294. doi: 10.17245/jdapm.2018.18.5.287. Epub 2018 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 30402548]

Boonsiriseth K, Sirintawat N, Arunakul K, Wongsirichat N. Comparative study of the novel and conventional injection approach for inferior alveolar nerve block. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2013 Jul:42(7):852-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.11.017. Epub 2012 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 23265758]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceThangavelu K, Kannan R, Kumar NS. Inferior alveolar nerve block: Alternative technique. Anesthesia, essays and researches. 2012 Jan-Jun:6(1):53-7. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.103375. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25885503]

Shirani M, Looha MA, Emami M. Comparison of injection pain levels using conventional and computer-controlled local anesthetic delivery systems in pediatric dentistry: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of dentistry. 2025 Jun:157():105770. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2025.105770. Epub 2025 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 40254248]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFlisfisch S, Woelber JP, Walther W. Patient evaluations after local anesthesia with a computer-assisted method and a conventional syringe before and after reflection time: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Heliyon. 2021 Feb:7(2):e06012. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06012. Epub 2021 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 33604465]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAraújo GM, Barbalho JC, Dias TG, Santos Tde S, Vasconcellos RJ, de Morais HH. Comparative Analysis Between Computed and Conventional Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block Techniques. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2015 Nov:26(8):e733-6. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002245. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26594989]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHelander EM, Kaye AJ, Eng MR, Emelife PI, Motejunas MW, Bonneval LA, Terracciano JA, Cornett EM, Kaye AD. Regional Nerve Blocks-Best Practice Strategies for Reduction in Complications and Comprehensive Review. Current pain and headache reports. 2019 May 23:23(6):43. doi: 10.1007/s11916-019-0782-0. Epub 2019 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 31123919]

Tzermpos FH, Cocos A, Kleftogiannis M, Zarakas M, Iatrou I. Transient delayed facial nerve palsy after inferior alveolar nerve block anesthesia. Anesthesia progress. 2012 Spring:59(1):22-7. doi: 10.2344/11-03.1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22428971]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAquilanti L, Mascitti M, Togni L, Contaldo M, Rappelli G, Santarelli A. A Systematic Review on Nerve-Related Adverse Effects following Mandibular Nerve Block Anesthesia. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2022 Jan 31:19(3):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031627. Epub 2022 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 35162650]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSilbert BI, Kolm S, Silbert PL. Postprocedural inflammatory inferior alveolar neuropathy: an important differential diagnosis. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology. 2013 Jan:115(1):e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.08.017. Epub 2012 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 23217545]

Chevalier V, Arbab-Chirani R, Tea SH, Roux M. Facial palsy after inferior alveolar nerve block: case report and review of the literature. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2010 Nov:39(11):1139-42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.04.049. Epub 2010 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 20605412]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaart JA, van Diermen DE, van Eijden TM. [Transient paresis after mandibular block anaesthesia]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor tandheelkunde. 2006 Oct:113(10):418-20 [PubMed PMID: 17058764]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHuang RY, Chen YJ, Fang WH, Mau LP, Shieh YS. Concomitant horner and harlequin syndromes after inferior alveolar nerve block anesthesia. Journal of endodontics. 2013 Dec:39(12):1654-7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.09.006. Epub 2013 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 24238467]