Introduction

Lymphogranuloma venereum is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, specifically the L1, L2, and L3 serovars, which differ from those responsible for more common Chlamydia infections.[1][2][3] Among these, L2b is the most common serovar of C trachomatis that is responsible for causing lymphogranuloma venereum.[4][5] Lymphogranuloma venereum tends to cause more severe inflammation and more aggressive infections compared to C trachomatis disorders from serovars A-K, where the resulting disease is typically relatively mild or asymptomatic.[3][6][7]

Lymphogranuloma venereum is rare in the United States compared to other STIs, such as gonorrhea, syphilis, or the more common but less severe chlamydia infections caused by serovars A-K.[2] However, accurate data on the prevalence and incidence of lymphogranuloma venereum are unavailable due to inadequate evaluations, misdiagnoses, diagnostic difficulties, and limited reporting requirements.[1][2] In August 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) presented data at the National STD Prevention Conference showing that STIs continue to rise at alarming rates. In 2023, nearly 2.3 million cases of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis were diagnosed in the United States, surpassing the previous record set in 2016 by more than 300,000 cases.

With the rise in transmission of STIs, rare diseases once considered eradicated have resurfaced. Lymphogranuloma venereum is one such example, although accurate data on its prevalence and incidence are unavailable due to inadequate evaluations, misdiagnoses, diagnostic difficulties, and limited reporting requirements.[1][2][8][9]

First described in 1833 by Wallace and later by Durand, Nicolas, and Favre in 1913, the infection was initially considered to be climatic in origin and identified as tropical bubo.[10][11] It was not until 1912 that Rost concluded that the disease was venereal in origin.[12]

Lymphogranuloma venereum presents with variable clinical manifestations depending on the site of bacterial inoculation.[13] The condition primarily affects the lymphatic system and lymph nodes. Classically, the infection characteristically presented with the development of self-limited genital ulceration and painful inguinal adenopathy or buboes.[13] If left untreated, the disease process was progressive and destructive, with systemic spread leading to several extra-genital manifestations.[13] With the advent of antibiotic therapy, lymphogranuloma venereum had largely disappeared from Western society.[14] However, since 2003, outbreaks of lymphogranuloma venereum have emerged in Western Europe, Australia, and North America, disproportionately affecting men who have sex with men (MSM), and the worldwide incidence is increasing.[15][16][17][18][19]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The risk of developing lymphogranuloma venereum is related to lifestyle and sexual practices. Acute infection requires direct inoculation of the C trachomatis bacteria into the host tissue. In the case of lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis, infection transmission is often through receptive anal intercourse. As with other STIs, promiscuity and intercourse with multiple partners place individuals at increased risk for contracting the disease.

As lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis has disproportionately affected homosexual men, studies have attempted to identify risk factors or behavioral patterns within this population that place an individual at increased risk for developing lymphogranuloma venereum. Using questionnaires to identify differences between asymptomatic and symptomatic homosexual men, the study found that those with lymphogranuloma venereum infections were more likely to have had unprotected receptive or insertive anal intercourse, including fisting; have had multiple partners or one-off sexual encounters; have concurrent recreational drug and alcohol use (gamma-hydroxybutyrate and methamphetamines most commonly reported); and have used shared sex toys.[20][21][22]

Epidemiology

Chlamydia is the most commonly reported infectious disease to the CDC, with more than 209,000 cases of syphilis, over 600,000 cases of gonorrhea, and over 1.6 million cases of chlamydia. C trachomatis is also the most common sexually transmitted disease worldwide, with over 100 million new cases annually, and the incidence is increasing.[23][24][25]

Lymphogranuloma venereum is still relatively rare in the United States, although the incidence is increasing.[26] This condition is most commonly found in subtropical and tropical regions worldwide, such as Africa, India, Southeast Asia, South America, and the Caribbean, where it has primarily been a heterosexual disease.[2][27]

Lymphogranuloma venereum is estimated to account for 2% to 10% of all genital ulcers in Africa and Southeast Asia, with transmission believed to be primarily through asymptomatic carriers.[10][28][29] Lymphogranuloma venereum infections are frequently associated with HIV and other STIs.[14][30][31] In Western countries, lymphogranuloma venereum is disproportionately found among men with HIV who have sex with men, in whom it is considered endemic.[2][14] Conversely, the majority of patients with lymphogranuloma venereum are likely to be HIV-positive.[14]

Lymphogranuloma venereum most commonly presents in Western countries with proctocolitis, which can be an invasive, aggressive, systemic infection that can progress to strictures, colorectal fistulas, rectal discharge, anal pain, tenesmus, and fever.[32] Genital involvement of lymphogranuloma venereum in MSM populations is quite uncommon despite the high prevalence of lymphogranuloma venereal proctocolitis in this group.[33]

Prior to 2003, lymphogranuloma venereum was rare in the Western world and was primarily endemic to tropical regions, such as East and West Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean, with a low prevalence in the industrialized world.[34] As such, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, with input from the CDC, voted to cease mandated reporting of the disease in 1995.[35]

In 2003, an outbreak of lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis amongst HIV-positive MSM in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, occurred, which prompted a concerted effort to warn the international medical community.[18][36][37] Subsequent published case reports demonstrated the presence of lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis in multiple large European cities.[17][38] Western Europe and North American countries began to implement surveillance protocols amongst high-risk patients. Despite these efforts, a decade later, mandatory reporting of lymphogranuloma venereum was still not required in several European countries. Even today, only 24 states in the United States mandate the reporting of lymphogranuloma venereum cases to the CDC, which limits the available data to determine the true disease prevalence.

Accurate epidemiologic figures remain elusive, as it is still not universally mandated or required to report cases of lymphogranuloma venereum. Moreover, as noted in the 2016 European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) annual epidemiological report, present surveillance strategies focus primarily on high-risk populations, such as MSM and patients with HIV/AIDS or other STIs, making it difficult to generate data applicable to the general population.

Although determining the incidence and prevalence of lymphogranuloma venereum has been challenging, data reflect a disease on the rise that disproportionately affects MSM.[14][18]

- The ongoing data collection published by the ECDC has continued to show a rise in the incidence of lymphogranuloma venereum. In 2014, ECDC data compiled from 21 reporting European countries revealed 1416 reported cases that year alone, a 32% increase from 2013. The vast majority of cases reported in the ECDC data (87%) were noted to be from France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, with almost all cases reported being among MSM.

- A population-based incidence study conducted in Barcelona from January 2007 to December 2011 revealed a 1032% increase in incidence among MSM during the study period.[39] In the United States, specific data regarding lymphogranuloma venereum have not been available from the CDC. Notably, reported cases of Chlamydia infection in the United States have continued to increase annually, according to CDC surveillance data.

- Patients with HIV have been disproportionately affected by lymphogranuloma venereum infections.[14]

- In the ECDC data of patients with a known HIV status, 87% of confirmed lymphogranuloma venereum cases occurred in HIV-positive patients.

- A 2007 meta-analysis concluded that from 1996 to 2006, HIV-positive MSM accounted for 75% of lymphogranuloma venereum cases on average in Western Europe alone.[40]

- A prospective, multicenter study in Germany conducted from December 2009 to December 2010 evaluated the prevalence of multiple STIs among MSM. The findings revealed that 58% of patients who tested positive for lymphogranuloma venereum were also HIV-positive.[41]

- In a 2011 meta-analysis, 13 descriptive studies showed that at least two-thirds of MSM with lymphogranuloma venereum were co-infected with HIV.[14] In the same analysis, pooled data from 17 studies from 2000 to 2009 showed HIV-positive MSM were greater than 8 times as likely to have HIV (OR 8.19, 95% CI 4.68-14.33) than those who had non-lymphogranuloma venereum Chlamydia infections.[14] These data demonstrated an association stronger than other STIs that reemerged during the same timeframe.[14] Improved survival in the post-highly active antiretroviral therapy era and serosorting (the practice of using HIV status as a decision-making strategy when participating in sexual activity) were likely factors contributing to this association.[40]

Other prevalence estimates and case-control studies have shown that HIV-infected MSM are disproportionately affected by the emergence of lymphogranuloma venereum due to an underlying pathophysiologic mechanism. Brenchley et al proposed that acute and chronic HIV infections cause impairment or depletion of effector-type T cells in the gastrointestinal mucosa, resulting in rapid depletion of CD4+ T cells.[42] By decreasing and inhibiting mucosal immune integrity, HIV may facilitate other co-infections, such as syphilis and chlamydia.[43]

Moreover, the direct exposure and inoculation of bacteria into the rectal mucosa during receptive anal intercourse facilitates transmission in an already susceptible population. The susceptibility of HIV-infected individuals to acquiring lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis is likely a combination of high-risk sexual behavior and T-cell immunodeficiency.[42][43]

Pathophysiology

C trachomatis is a nonmotile, gram-negative intracellular bacterium that is transmissible through anal, oral, or vaginal contact and can penetrate skin and mucus membranes.[10][44] The organism is an obligate intracellular pathogen capable of reproducing intracellularly through binary fission.[10] The organism may affect epithelial cells of the mouth and oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract (primarily the rectum), and the urogenital system.[23][24]

Bacterial growth creates perinuclear microcolonies, which proliferate, eventually causing cell lysis.[10] The bacteria then spread through the lymphatics, creating lymphangitis.

The clinical course of the disease depends on the site of bacterial inoculation. From the inoculation site, C trachomatis passes through lymphatic channels. C trachomatis penetrates and multiplies within the mononuclear phagocytes inside lymph nodes as it passes through them, inducing a severe lymphoproliferative reaction.[2][10][45] Infectivity is mediated by the organism binding to epithelial cells through a heparin sulfate–like ligand.[45]

Infected lymph nodes develop a severe inflammatory reaction and progress to lymphangitis with painful buboes, which ulcerate, creating fistulas, abscesses, and strictures.[46] These lesions can extend into neighboring areas, such as the rectum, leading to fistulas, perirectal abscess formation, proctitis, fibrosis, and anal strictures.[46]

Lymphogranuloma venereum can cause a broad spectrum of human diseases, generally involving the genitourinary tract, female reproductive organs (salpingitis), gastrointestinal tract (proctocolitis), joints, and lungs.[10]

Histopathology

Histopathologic findings are often nonspecific, and distinguishing lymphogranuloma venereum from other inflammatory or infectious etiologies may be challenging. For example, lymph node biopsies are typically nonspecific. However, large intracytoplasmic basophilic inclusion bodies, called Gamna-Favre bodies, may be observed in affected endothelial cells of patients with lymphogranuloma venereum. These inclusion bodies are made of degenerated nuclear material and are only found in lymphogranuloma venereum.

On rectal biopsy, inflammation, cryptitis, and crypt abscesses are common histologic findings. Cryptitis, crypt abscess formation, increased inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, granuloma formation, and transmural inflammation may be evident.[47] Rectal crypt architectural distortion may be present but is relatively uncommon.

These findings can render a histopathologic diagnosis indistinguishable from that of inflammatory bowel disease. Therefore, it is reasonable to ask pathologists to rule out viral etiologies such as herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and other sexually transmitted infectious agents. Nucleic acid amplification testing for lymphogranuloma venereum is often required for a diagnosis.

History and Physical

Clinically, lymphogranuloma venereum is primarily a lymphatic infection that typically progresses through 3 stages. During the disease course, patients may experience symptoms from the initial infection, systemic dissemination, or the development of chronic inflammation. Symptoms vary depending on the stage at which a patient presents and the site of bacterial inoculation (see Table. Differential Diagnosis of Lymphogranuloma Venereum Proctocolitis). Transmission of the infection is by anal, oral, or vaginal sexual activity.

High-risk factors for lymphogranuloma venereum infections include the following:

- Being born to a mother known to have chlamydia.

- Engage in anal or oral group sex without appropriate barrier protection.

- Having sexual activity without condom protection.

- Individuals with HIV-positive, gonorrhea, or hepatitis C.

- Lower socioeconomic status.

- MSM who represent the group at the highest overall risk.

- Multiple sexual partners (more than 2 within the past year).

- Past medical history of a sexually transmitted illness.

- Recent travel to an area where lymphogranuloma venereum is endemic.

- Sexually active individuals between the ages of 15 and 40 are the highest-risk age group.

Other known high-risk activities include anonymous sexual partnering, street involvement, history of substance abuse, and engaging in high-risk activities, such as fisting.

Primary Lymphogranuloma Venereum

Primary lymphogranuloma venereum typically develops after an incubation period of 3 to 30 days, during which the first manifestations of the disease may become apparent.[2][10] A transient painless erosion, nodule, papule, pustule, or ulcer frequently forms on the external genitalia at the inoculation site; this stage often passes unnoticed (see Image. Lymphogranuloma Venereum).[13] Possible inoculation sites include the male and female genitalia, penis, vagina, cervix, anus, and oral cavity.[2]

The resurgence of lymphogranuloma venereum has disproportionately affected men who have anal intercourse. As such, most new cases (approximately 96% in earlier estimates) present signs and symptoms of proctitis as their initial symptom.[48]

Following invasion of the rectal mucosa by C trachomatis, patients may present with anorectal bleeding, mucoid and purulent anal discharge, rectal pain, tenesmus, and a change in bowel habits, including constipation.[2][48] Cross-sectional imaging may reveal colorectal wall thickening, and gross endoscopic findings can mimic those of acute infectious proctocolitis or an acute flare of inflammatory bowel disease. Endoscopic findings may include mucosal edema, erythema, and ulceration. Endoscopic biopsies performed during this phase often yield nonspecific findings of inflammation, such as cryptitis and crypt abscess formation. The initial presentation may be a presumed infectious colitis refractory to traditional first-line antibiotic therapy and new-onset rectal bleeding. Underlying malignancy must be ruled out.

Secondary Lymphogranuloma Venereum

Secondary lymphogranuloma venereum occurs 2 to 6 weeks after initial exposure to the pathogen as the C trachomatis bacteria invade the lymphatic system.[2][10] Painful inguinal and femoral lymphadenopathy (buboes) may develop, which is often the primary clinical symptom as infected regional lymph nodes become firm, swollen, and sore.[2][6] Systemic spread through the lymphatic system can lead to constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, generalized malaise, myalgias, arthralgias, pneumonitis, and hepatitis, which may be accompanied by abnormal liver enzymes.[2]

An inguinal syndrome may occur in some patients who have concurrently developed genital lymphogranuloma venereum infections. Classically, the inguinal syndrome was the first manifestation of disease in heterosexual males affected by genital lymphogranuloma venereum. The majority of cases present with unilateral painful inguinal lymph node enlargement and abscess formation. Involvement may be limited to isolated lymph nodes or groups of nodes, which can coalesce into a swollen, necrotic, purulent, and fluctuant mass known as a bubo.[2] One-third of buboes may rupture, while the rest develop into solid masses.[2]

Merged regional lymph nodes may also develop into abscesses, which can form sinus tracts if they rupture.[2] Depending on the inoculation site, this process may occur in the intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal, femoral, inguinal, or cervical lymph node chains.[2][49]

The groove sign, first described by Greenblatt in 1953, is pathognomonic of genital lymphogranuloma venereum but is present in less than 20% of cases.[49][50][51] This sign—sometimes called Greenblatt's sign—develops as the tough inguinal ligament is preserved despite the involvement of swollen, bulging, adjacent inguinal (above) and femoral (below) lymph node chains, creating a characteristic groove.[10][50][51]

Systemic spread through the lymphatic system can lead to constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, generalized malaise, myalgias, arthralgias, pneumonitis, and hepatitis, which may be accompanied by abnormal liver enzymes.[2][52]

Rare complications of the disease during this stage include myocarditis, aseptic meningitis, and ocular inflammatory diseases.[49] Case reports describe reactive arthritis following confirmation of lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis.[53]

The initial genital ulcer typically resolves before or during this secondary phase of the infection, but symptoms of proctocolitis tend to persist.[2]

In lymphogranuloma venereum, proctocolitis manifests as an anorectal syndrome. Hemorrhagic proctitis is the most common current presentation in MSM due to the direct transmission of C trachomatis to the rectal mucosa.[2] This condition can also occur in women who have had rectal exposure to an infected man.[2][46] Direct bacterial dissemination to the deep iliac and perirectal lymph nodes may cause lower abdominal and lower back pain. Lymph node involvement is often less evident in this patient population than in genital lymphogranuloma venereum and may only present as local lymph node prominence on cross-sectional imaging.

Tertiary Lymphogranuloma Venereum

Tertiary lymphogranuloma venereum, also called genitoanorectal syndrome, is characterized by permanent lymphatic damage and demonstrates progressive, local tissue destruction and chronic inflammation caused by the ongoing, untreated infection.[2] Chronic perirectal lymphatic obstruction can produce hemorrhoid-like swellings called lymphorroids.[2] Proctocolitis is the most common presentation overall, especially in the MSM population and in women who indulge in rectal intercourse.[28]

Tertiary lymphogranuloma venereum is more common in women as they typically lack significant symptoms during the primary or secondary lymphogranuloma venereum stages.

Fistulas, strictures, and stenosis involving the inguinal glands, genitalia, and rectum may form as a result of chronic lymphangitis and progressive sclerosing fibrosis, sometimes closely mimicking inflammatory bowel disease.[2] Rectal stenosis and perirectal pathology, including abscesses, fistulas, strictures, and ulcers, can develop.

The characteristic distortion from penile and scrotal edema due to lymphogranuloma venereum has sometimes been described as a saxophone penis.[54]

Frozen pelvis syndrome can cause chronic pelvic pain, and some patients may develop genital lymphedema (elephantiasis).[32][55] Persistent lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis can lead to strictures, which may subsequently develop into megacolon.[56] Lymphogranuloma venereum may also be the source of fevers of unknown origin and unexplained rectal pain.

Table 1. Differential Diagnosis of Lymphogranuloma Venereum Proctocolitis

| Stage of Infection | Symptoms | Potential Differential Diagnoses |

| Primary lymphogranuloma venereum |

Genital lymphogranuloma venereum

Anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum

|

Genital lymphogranuloma venereum

Anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum

|

| Secondary lymphogranuloma venereum |

Genital lymphogranuloma venereum

Anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum

Both

|

Genital lymphogranuloma venereum

Anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum

Both

|

| Tertiary lymphogranuloma venereum |

Genital lymphogranuloma venereum

Anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum

|

Genital lymphogranuloma venereum

Anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum

|

Evaluation

The diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum is based on clinical history, physical findings, diagnostic suspicion, the presence of lymphogranuloma venereum–risk factors, epidemiologic information, regional prevalence, and a positive nucleic acid amplification testing finding of C trachomatis at the symptomatic anatomic site when other causes for the suspicious abnormalities, such as genital, oral, or rectal ulcers; inguinal lymphadenopathy; or proctitis, have been excluded.[2][6][57][58]

Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing

Nucleic acid amplification testing is the most sensitive and preferred initial test for suspected C trachomatis infections.[59] This testing is performed on swabs from involved lymph nodes, anogenital ulcers, rectal mucosa, or anogenital lesions and is the initial investigation of choice.[32][55][60][61] Nucleic acid amplification testing techniques include polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, transcription-mediated amplification, or strand displacement amplification.[62][63][64][65][66] These assays demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity (sensitivity from 91.4% to 100% and specificity from 98.3% to 98.8%, depending on the nucleic acid amplification testing technique used) for chlamydia.[67] Nucleic acid amplification testing generally identifies 10% to 50% more chlamydial infections than cultures or other means.[55][68]

Not all states currently require mandatory reporting of confirmed lymphogranuloma venereum disease to the appropriate local or state agency, but it should be strongly encouraged.

Appropriate samples for lymphogranuloma venereum nucleic acid amplification testing may include: [32][69]

- A swab of exudate from the base of primary anogenital ulcers

- A swab from the rectal mucosa when anorectal involvement is suspected

- Aspirate from enlarged or fluctuant lymph nodes or buboes

- If no fluctuant nodes are found, a small volume (<0.5 mL) of normal saline may be injected into the node and then aspirated

Although PCR testing is definitive and can differentiate lymphogranuloma venereum serovars from other, less morbid chlamydial infections, it is not widely available. Nucleic acid amplification testing can detect all chlamydial infections, is extremely sensitive, and is more widely available, although it cannot distinguish lymphogranuloma venereum–causing chlamydia from the less morbid serovars.[28][59]

Chlamydial serology testing, including immunoassays and microimmunofluorescence, may confirm elevated antibody levels but is infrequently used clinically to diagnose lymphogranuloma venereum due to limited availability, interpretative difficulties, lack of definitive results, and lack of standardization. Complement fixation testing can demonstrate a strong immune response to lymphogranuloma venereum, with a titer reading >1:64 or a 4-fold increase from baseline being considered diagnostic in patients suspected of having the infection.[2][46][70]

Serological testing may be considered when nucleic acid amplification testing or similar methods are not available and can serve as an adjunct to extragenital chlamydia cultures.[55] This testing is typically reserved for patients with a high suspicion of lymphogranuloma venereum infection, such as MSM, those with suggestive symptoms, sexual contact with known or suspected individuals infected with lymphogranuloma venereum, risky sexual behavior, or HIV-positive status.[55] However, serology is not recommended for routine lymphogranuloma venereum testing due to problems with interpretation, including cross-reactivity, high degree of variability in titer levels, and difficulty in evaluating post-therapeutic antibody levels.[55]

Despite its technical challenges in certain situations, needle aspiration is the preferred method for obtaining samples for culture. As C trachomatis is an intracellular organism, samples for culture must contain cellular material, as routine bacterial smears and cultures are insufficient to definitively diagnose this organism.[2] Cell cultures are highly specific, but they are technically more difficult and expensive than non-culture testing.[2][59] They also have a relatively low reported sensitivity (60%-80%).[2][59] Incorrect negative results from a rectal chlamydial culture can occur in up to 50% of cases.[55] A positive culture is not always possible, even in known lymphogranuloma venereum infections.[2]

When a patient with known risk factors has high clinical suspicion of lymphogranuloma venereum, attempts should be made to identify C trachomatis. As standard nucleic acid amplification testing cannot differentiate the C trachomatis serovars, patients suspected of lymphogranuloma venereum with a positive nucleic acid amplification test for chlamydia should receive the complete antibiotic treatment for lymphogranuloma venereum.[24]

Lymphogranuloma Venereum Proctocolitis

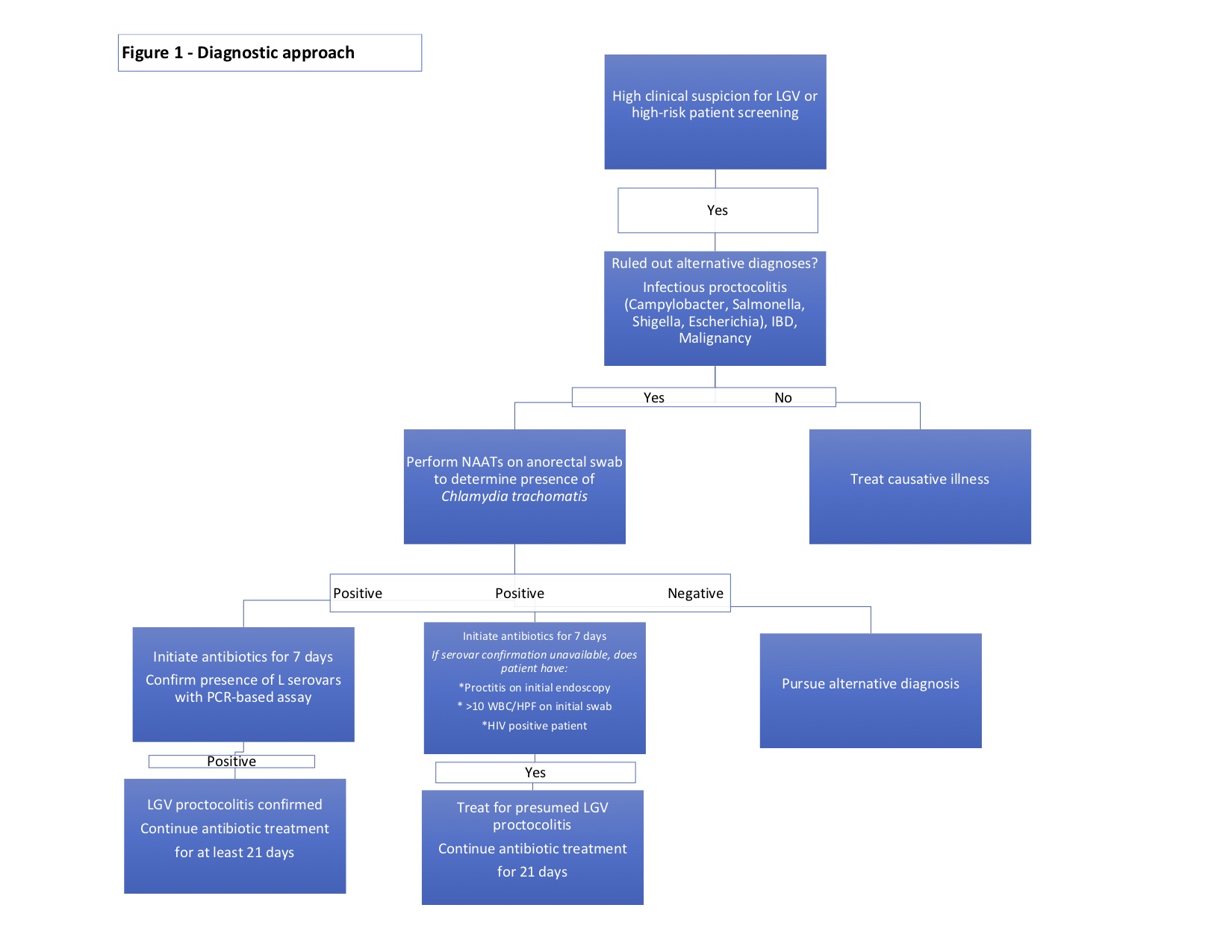

The diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis follows a stepwise approach (see Image. Diagnostic Approach to Lymphogranuloma Venereum Proctocolitis). Initial evaluation includes routine laboratory tests and stool cultures to rule out more common infectious entities, such as Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus, Cryptosporidium, and Clostridium difficile. Additionally, testing for sexually transmitted infections such as syphilis, gonorrhea, non-lymphogranuloma venereum strains of chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus is performed.[71] Inflammatory bowel disease and malignancy can present with similar clinical symptoms.[71]

Cross-sectional imaging and endoscopic evaluation through sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy can help identify the extent of the disease and any extraintestinal manifestations. An endoscopic biopsy can be used to rule out viral etiologies, malignancy, or underlying inflammatory conditions. However, endoscopic and histologic findings of lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis are often nonspecific and mimic other disease processes.[72]

A rectal Gram stain with a high number of white blood cells (>10 WBCs) suggests rectal lymphogranuloma venereum.[21][73] A definitive lymphogranuloma venereum diagnosis can be made only with lymphogranuloma venereum-specific molecular testing (genotyping by nucleic acid amplification testing or PCR testing), which can differentiate lymphogranuloma venereum serovars from less morbid C trachomatis strains in rectal and genital specimens.[24] This differentiation cannot generally be achieved through standard nucleic acid amplification testing.

Following confirmation of infection, it is recommended to identify the L1-L3 serovars, if possible. Lymphogranuloma venereum biovar–specific DNA nucleic acid amplification testing can be performed from the initial anorectal swab sample using PCR-based assays.[32][55][74] If positive, the recommended treatment is a 21-day course of antibiotics. Unfortunately, there is a lack of universal access to biovar-specific confirmatory testing.[34] When nucleic acid amplification testing is unavailable, Chlamydia genus-specific serological assays, such as complement fixation and L-type immunofluorescence, are options; however, these tests exhibit lower sensitivity and specificity. When serovar confirmation is unavailable, clinicians should consider initiating a 21-day course of antibiotic therapy in patients meeting one of the following criteria: [2][24]

- The presence of proctitis on initial colonoscopy or anoscopy

- More than 10 WBCs per high-powered field on initial anorectal smear

- HIV-positive status

Although these diagnostic strategies are essential in symptomatic patients, they are also useful in screening asymptomatic, high-risk individuals who engage in receptive anal intercourse.

Untreated lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis can lead to serious complications, including rectal and anal strictures, perirectal abscesses, fistulas, and masses that can mimic rectal malignancies.[75][76][77]

The CDC recommends that all patients with acute proctitis be tested for a possible lymphogranuloma venereum infection.[24] Patients with severe symptoms of proctitis and a positive nucleic acid amplification testing for C trachomatis should receive a full course of lymphogranuloma venereum therapy.[24] Anoscopy should be performed, and a gram-stained rectal smear should be examined for leukocytes (≥10 WBCs on a rectal gram-stained smear is suggestive of lymphogranuloma venereum).[21][24][73] In addition, patients should be tested for herpes simplex virus through nucleic acid amplification testing; Neisseria gonorrhoeae by culture or nucleic acid amplification testing; Treponema pallidum using serologic testing and darkfield microscopy, if available; and C trachomatis through nucleic acid amplification testing.[23][24] If available, nucleic acid amplification testing or PCR testing for C trachomatis serovars should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum.[24][68][78]

Differentiating lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis from irritable bowel disease is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.[2][23][72][79] This task is becoming increasingly challenging due to the rising incidence of lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis, especially in high-risk populations. However, the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease is also increasing, and there is substantial overlap in the clinical presentation of the 2 disorders.[2][23][72][80][81] In addition, their endoscopic and histological features are similar.[2][23][72][82][83]

Lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis may demonstrate nonspecific abscesses, granulomas, and ulcerations.[72][82] If longstanding, fistulas, granulomas, and strictures may develop, closely resembling Crohn disease endoscopically and histologically.[72][83]

Nucleic acid amplification testing for C trachomatis is essential for diagnosing lymphogranuloma venereum, along with PCR serovar confirmation, if available.[72][78]

The rate of positive rectal C trachomatis findings is reported as 10% to 15% in the MSM community and 5% to 9% in women.[23][84] Most such patients are asymptomatic, with only 15% to 20% reporting symptomatic proctitis.[23] Patients who test positive for non-lymphogranuloma venereum rectal infections tend to be asymptomatic or have only mild symptoms.[23] Nevertheless, antibiotic treatment is still recommended.[23]

All known contacts of individuals infected with lymphogranuloma venereum should be promptly tested and treated.

Lymphogranuloma venereum is responsible for 10% to 25% of all rectal infections caused by C trachomatis.[23][85][86][87]

Lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis should be considered whenever patients are in a high-risk group, have severe proctocolitis symptoms, or do not respond to standard treatments.[2][47][69]

Treatment / Management

Current CDC guidelines recommend treating patients with clinical features consistent with lymphogranuloma venereum infection, including proctocolitis, genital ulcer disease, and lymphadenopathy.[88] The mainstay of therapy in lymphogranuloma venereum infection remains antibiotic use.

Multiple sources, including those from American, Canadian, UK, and European, recommend first-line therapy with doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 21 days, which provides a cure rate of over 98.5%.[13][32][69][89] Lymphogranuloma venereum requires a longer duration of antibiotic therapy to achieve a cure than other chlamydial infections. This recommendation is based on extensive evidence of clinical cure rates and the finding that lymphogranuloma venereum RNA can be detected for up to 16 days during therapy.[55][89][90] In resistant or intractable cases, prolonged therapy may be needed.[90][91](A1)

Erythromycin 500 mg orally 4 times daily can be used for second-line therapy and in pregnant patients.[88][92][93][94][95] (A1)

Azithromycin 1 g orally once weekly for 3 weeks is an attractive regimen that may improve patient compliance and is recommended during pregnancy; however, no controlled trials currently support the efficacy of this therapy.[96]

All current and recent (within 60 days) sexual partners of patients known or suspected to be infected with lymphogranuloma venereum should be screened to prevent reinfection and further spread of the disease.[2][55] Ultimately, prevention and the use of appropriate contraception are points of emphasis during encounters with at-risk patients.(B2)

A second approach is an option in patients with symptoms consistent with lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis. Clinicians can consider initiating empiric therapy with doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days in conjunction with a single intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone 250 mg while laboratory tests are pending. If laboratory testing confirms a Chlamydia infection, doxycycline should be continued for a total of 21 days or longer if the patient continues to manifest symptoms (see Image. Diagnostic Approach to Lymphogranuloma Venereum Proctocolitis).[55](B2)

Patients being treated for lymphogranuloma venereum should avoid all sexual contact or intercourse until their antibiotic therapy course is completed and all related symptoms have resolved.[2][55](B2)

Management of Contacts, Follow-ups, and Special Patient Situations

The CDC recommends presumptive treatment for lymphogranuloma venereum in at-risk individuals presenting with symptoms of proctocolitis, severe inguinal lymphadenopathy with bubo formation, or current or recent genital ulcers when other causes have been ruled out. Patients should be monitored regularly until all signs and symptoms have resolved.

Patients diagnosed with lymphogranuloma venereum should undergo repeat testing for chlamydia approximately 3 months after completing therapy. If this is not possible, retesting should be done at least within 1 year. Patients and their sexual partners should also be tested for other sexually transmitted infections such as gonorrhea, syphilis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and especially HIV.[2][55](B2)

Sexual partners and contacts of patients diagnosed with lymphogranuloma venereum should be evaluated, examined, and tested for chlamydial infection.[2][6] This recommendation also applies to contacts of patients with probable lymphogranuloma venereum.[2][6] Asymptomatic partners of patients with lymphogranuloma venereum should be presumptively treated with a standard chlamydia antibiotic regimen of doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days.[97] However, some experts recommend a complete 21-day course of antibiotics for all contacts of confirmed and probable lymphogranuloma venereum infections, as a 7-day treatment course is insufficient for lymphogranuloma venereum.[55][98] This approach exceeds the recommendations in most published guidelines but avoids possible inadequate treatment of lymphogranuloma venereum due to testing inadequacies, patient confusion, non-compliance, missed follow-up appointments, and communication failures.[2][55](B2)

Azithromycin at 1 g weekly for 3 weeks is recommended in pregnant patients. Follow-up testing is advised 1 month after completing therapy.[2][6]

Asymptomatic patients with lymphogranuloma venereum should also be treated with a 7-day course of 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily; however, some have recommended a complete 21-day course to ensure adequate treatment.[2][6][55][97][98][99] In these cases, a single 1-g dose of azithromycin has been suggested as an alternative regimen; however, its efficacy has also been questioned.[91](B2)

Patients with lymphogranuloma venereum who test positive for HIV should receive the same antibiotic regimen for C trachomatis as those without HIV. However, prolonged therapy may be required.

Surgery is not a primary treatment for lymphogranuloma venereum but may be needed to manage complications such as draining abscesses and buboes, treating fistulas, and managing sinus tracts. Buboes and abscesses with fluctuation are best treated by puncture with a large-bore needle and syringe, as standard surgical incision and drainage procedures are not recommended, as they may lead to the development of permanent fistulas.[10]

Residual fibrotic lesions and areas of significant tissue destruction may require formal surgical repair with possible reconstruction of the genitourinary tract.[10] Rectal strictures are generally treated with dilation.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum includes the following:

- Primary lymphogranuloma venereum

- Altered bowel habits, pain, and bloody diarrhea: Dysentery and inflammatory bowel disease

- Diarrhea or pain: Infectious proctocolitis due to common organisms or other STIs such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and Entamoeba histolytica

- Malignancy

- Pain and altered bowel habits: Irritable bowel syndrome

- Rectal pain and bloody output: Hemorrhoids

- Secondary lymphogranuloma venereum

- Abnormal liver function tests: Hepatitis

- Cat-scratch disease

- Chancroid

- Constitutional symptoms, myalgias, and arthralgias: Routine infectious colitis and influenza

- Granuloma inguinale

- Herpes virus

- Malignancy: Rectal carcinoma and lymphoma

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Syphilis

- Tertiary lymphogranuloma venereum

- Fistula or stricture formation: Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease, ischemic colitis, and ulcerative colitis)

- C. difficile megacolon

- Infective proctitis

- Post-radiation therapy

- Malignancy

Prognosis

Prognosis is fair and hinges on prompt recognition of the condition, patient compliance with prolonged antibiotic therapy, and avoidance of high-risk behaviors. Recurrence is possible with repeat exposure.

Complications

Complications of lymphogranuloma venereum arise from persistent, untreated infection and typically signify progression to tertiary lymphogranuloma venereum. These complications include the following:

- Abscess formation

- Cardiac involvement

- Cervical swelling

- Chronic pelvic pain (frozen pelvis syndrome)

- Colorectal strictures and stenoses

- Encephalitis (rare)

- Fistulas, sinus tracts, and ulcers

- Genital swelling (permanent)

- Hepatic involvement and hepatitis

- Infertility

- Lymphadenopathy

- Lymphatic blockage with edema and swelling

- Lymphorrhea

- Ocular disorders

- Oral ulcers

- Pneumonia

- Prolonged groin and rectal pain

- Reactive arthropathy

- Rectal masses

- Rectal stenosis

- Rectovaginal abnormalities

- Salpingitis

- Scarring

Consultations

A multidisciplinary approach is often necessary in managing lymphogranuloma venereum. A gastroenterologist may be needed for the initial evaluation of patients presenting with proctocolitis. A gynecologist may be involved in vaginal lesions, salpingitis, and female infertility. A urologist should be consulted for genitourinary issues, and an ENT specialist for oral lesions. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist is necessary for HIV-co-infected patients and those with refractory disease. Late-stage illness may require surgical consultation if fistulas, megacolon, stenoses, or strictures develop.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Early recognition of the signs and symptoms of lymphogranuloma venereum is key to improving outcomes. Delays in diagnosis may be related to disease mimicry or failure to elicit an adequate sexual history from patients on intake. High-risk individuals should receive education on early signs and symptoms, means of transmission, prevention of transmission through safe sexual practices, and risks associated with having multiple sexual partners. In addition, testing should be offered and considered in high-risk, asymptomatic patients or those who present with other STIs.

Pearls and Other Issues

Universal rectal screening for all patients with proctocolitis can identify an additional 34% of individuals with lymphogranuloma venereum who have asymptomatic disease.[32][47][100]

- Although high-risk populations more commonly present with lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis, it is crucial to remember that heterosexual patients can develop lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis through unprotected anal intercourse with an infected individual.

- Asymptomatic, high-risk individuals may benefit from testing during routine visits at periodic intervals.

- Partners of individuals infected with lymphogranuloma venereum should be tested and treated if they are found to be positive for the disease.

- Some experts recommend a complete 21-day course of antibiotic therapy to ensure adequate treatment.

- Pregnant and lactating women should not be treated with doxycycline during the second and third trimesters due to the risk of discoloration of fetal and newborn teeth and bones.[101][102]

- Erythromycin is recommended as the first-line treatment in these cases.

- HIV-co-infected individuals may experience a delay in the resolution of their lymphogranuloma venereum disease and may require prolonged courses of therapy.

- Inguinal lymphogranuloma venereum may also require a longer duration of antibiotic therapy than the typically recommended 21-day course of doxycycline.[91]

- Urethral chlamydia infections in MSM may be caused by serovars that require a longer duration of antibiotic therapy than the standard regimen.[91]

- The incidence of genital involvement in lymphogranuloma venereum is relatively low among MSM, despite a very high rate of lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis.[33]

- Some studies have suggested that the recommended 1-g azithromycin therapy for sexual contacts, as recommended in published guidelines, may be insufficient to prevent lymphogranuloma venereum infections.[91]

- No vaccine is currently available against C trachomatis. Consistent condom use is the most effective method of primary prevention of lymphogranuloma venereum and other STIs, such as HIV.

- Identification, notification, testing, and treatment of all sexual contacts of infected individuals are essential for controlling outbreaks and reducing transmission. This process may include notification by public health departments, individual physicians, relying on the primary index patient to notify sexual contacts, and similar methods to screen all individuals who may be infected.

- Active screening for genital chlamydia infection has been shown to reduce the incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease.[24]

- When lymphogranuloma venereum is suspected, testing for HIV and other STIs should be performed.[2]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The prevention and treatment of lymphogranuloma venereum infections, particularly proctocolitis, require a collaborative, multispecialty approach, involving nurses and clinicians, as well as support from local outreach programs, local and regional health departments, governmental services, and public health agencies. As evidenced in the early 2000s, the European Surveillance of Sexually Transmitted Infections alert system in Europe successfully provided clinicians with local alerts of disease activity and helped coordinate outbreak control. As prompt recognition is critical, similar systems should be fostered in the United States, and clinicians should be encouraged to report to local agencies.

As STIs continue to rise at alarming rates, clinicians across all specialties must continue to educate patients on safe sexual practices and how to identify the signs and symptoms of the disease. Initiating and supporting high-risk community outreach groups and screening initiatives for high-risk populations may help reduce the stigma associated with testing and promote eradication. Overall, lifestyle choices, sexual preferences, and HIV co-infection remain the strongest risk factors for developing lymphogranuloma venereum. Frequent reiteration of safe practices by multiple providers across multiple specialties may reinforce the importance of and promote ongoing healthy patient practices.

The diagnosis and management of lymphogranuloma venereum infection require an interprofessional team approach involving clinicians, mid-level practitioners, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. In most cases, clinicians diagnose and prescribe treatment, although they often require a consultation with infectious disease specialists. Pharmacists play a crucial role in verifying the appropriate selection and dosing of antibiotics, and they communicate any concerns or recommendations directly to the prescribing clinician or nursing team. This collaborative model promotes safe, effective, and patient-centered care.

Nurses play a key role in providing patient education and counseling to promote early symptom recognition and support preventive strategies—efforts that should be reinforced by both clinicians and pharmacists. Pharmacists are responsible for reviewing the patient's medication regimen for potential drug-drug interactions and promptly alerting the nursing staff or prescribing clinician if any are identified. Both nurses and pharmacists contribute to verifying treatment adherence, educating patients on proper medication use and dosing, and reporting any issues that may affect therapy. The clinician can then adjust the treatment plan as needed based on this feedback. These interprofessional strategies are essential for achieving optimal patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Diagnostic Approach to Lymphogranuloma Venereum Proctocolitis. The image outlines a stepwise diagnostic approach for lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis, guiding clinicians through testing, ruling out alternative infections, and determining appropriate treatment based on nucleic acid amplification test results and clinical criteria. LGV, Lymphogranuloma venereum; IBD, Inflammatory bowel disease; NAATs, nucleic acid amplification tests; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; WBC/HPF, white blood cells per high-powered field.

Illustration by K Humphreys

Contributed by MD Sheinman, DO

References

de Voux A, Kent JB, Macomber K, Krzanowski K, Jackson D, Starr T, Johnson S, Richmond D, Crane LR, Cohn J, Finch C, McFadden J, Pillay A, Chen C, Anderson L, Kersh EN. Notes from the Field: Cluster of Lymphogranuloma Venereum Cases Among Men Who Have Sex with Men - Michigan, August 2015-April 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2016 Sep 2:65(34):920-1. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6534a6. Epub 2016 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 27583686]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCeovic R, Gulin SJ. Lymphogranuloma venereum: diagnostic and treatment challenges. Infection and drug resistance. 2015:8():39-47. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S57540. Epub 2015 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 25870512]

Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sexually transmitted infections. 2002 Apr:78(2):90-2 [PubMed PMID: 12081191]

Marangoni A, Foschi C, Tartari F, Gaspari V, Re MC. Lymphogranuloma venereum genovariants in men having sex with men in Italy. Sexually transmitted infections. 2021 Sep:97(6):441-445. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054700. Epub 2020 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 33106439]

La Rosa L, Svidler López L, Entrocassi AC, López Aquino D, Caffarena D, Büttner KA, Gallo Vaulet ML, Rodríguez Fermepin M. Chlamydia trachomatis anorectal infections by LGV (L1, L2 and L2b) and non-LGV serotypes in symptomatic patients in Buenos Aires, Argentina. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2021 Dec:32(14):1318-1325. doi: 10.1177/09564624211038384. Epub 2021 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 34392724]

O'Byrne P, MacPherson P, DeLaplante S, Metz G, Bourgault A. Approach to lymphogranuloma venereum. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2016 Jul:62(7):554-8 [PubMed PMID: 27412206]

White JA. Manifestations and management of lymphogranuloma venereum. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2009 Feb:22(1):57-66. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328320a8ae. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19532081]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRönn M, Hughes G, White P, Simms I, Ison C, Ward H. Characteristics of LGV repeaters: analysis of LGV surveillance data. Sexually transmitted infections. 2014 Jun:90(4):275-8. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051386. Epub 2014 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 24431182]

Kapoor S. Re-emergence of lymphogranuloma venereum. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2008 Apr:22(4):409-16. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02573.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18363909]

Cunha Ramos M, Nicola MRC, Bezerra NTC, Sardinha JCG, Sampaio de Souza Morais J, Schettini AP. Genital ulcers caused by sexually transmitted agents. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2022 Sep-Oct:97(5):551-565. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2022.01.004. Epub 2022 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 35868971]

Stammers FA. Lymphogranuloma Inguinale (Tropical Bubo). British medical journal. 1943 May 29:1(4299):660-1 [PubMed PMID: 20784853]

COUTTS WE. Lymphogranuloma venereum; a general review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1950:2(4):545-62 [PubMed PMID: 15434659]

Garcia MR, Leslie SW, Wray AA. Sexually Transmitted Infections. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809643]

Rönn MM, Ward H. The association between lymphogranuloma venereum and HIV among men who have sex with men: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC infectious diseases. 2011 Mar 18:11():70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-70. Epub 2011 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 21418569]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRichardson D, Goldmeier D. Lymphogranuloma venereum: an emerging cause of proctitis in men who have sex with men. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2007 Jan:18(1):11-4; quiz 15 [PubMed PMID: 17326855]

Savage EJ, van de Laar MJ, Gallay A, van der Sande M, Hamouda O, Sasse A, Hoffmann S, Diez M, Borrego MJ, Lowndes CM, Ison C, European Surveillance of Sexually Transmitted Infections (ESSTI) network. Lymphogranuloma venereum in Europe, 2003-2008. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2009 Dec 3:14(48):. pii: 19428. Epub 2009 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 20003898]

Otani M, Rowley J, Grankov V, Kuchukhidze G, Bivol S, WHO European Region non-EU/EEA STI Surveillance network. Sexually transmitted infections in the non-European Union and European Economic Area of the World Health Organization European Region 2021-2023. BMC public health. 2025 Apr 25:25(1):1545. doi: 10.1186/s12889-025-22630-6. Epub 2025 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 40281539]

van Aar F, Kroone MM, de Vries HJ, Götz HM, van Benthem BH. Increasing trends of lymphogranuloma venereum among HIV-negative and asymptomatic men who have sex with men, the Netherlands, 2011 to 2017. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2020 Apr:25(14):. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.14.1900377. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32290900]

Williamson DA, Chen MY. Emerging and Reemerging Sexually Transmitted Infections. The New England journal of medicine. 2020 May 21:382(21):2023-2032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1907194. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32433838]

Macdonald N, Sullivan AK, French P, White JA, Dean G, Smith A, Winter AJ, Alexander S, Ison C, Ward H. Risk factors for rectal lymphogranuloma venereum in gay men: results of a multicentre case-control study in the U.K. Sexually transmitted infections. 2014 Jun:90(4):262-8. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051404. Epub 2014 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 24493859]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePallawela SN, Sullivan AK, Macdonald N, French P, White J, Dean G, Smith A, Winter AJ, Mandalia S, Alexander S, Ison C, Ward H. Clinical predictors of rectal lymphogranuloma venereum infection: results from a multicentre case-control study in the U.K. Sexually transmitted infections. 2014 Jun:90(4):269-74. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051401. Epub 2014 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 24687130]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBoutin CA, Venne S, Fiset M, Fortin C, Murphy D, Severini A, Martineau C, Longtin J, Labbé AC. Lymphogranuloma venereum in Quebec: Re-emergence among men who have sex with men. Canada communicable disease report = Releve des maladies transmissibles au Canada. 2018 Feb 1:44(2):55-61 [PubMed PMID: 29770100]

Hall R, Patel K, Poullis A, Pollok R, Honap S. Separating Infectious Proctitis from Inflammatory Bowel Disease-A Common Clinical Conundrum. Microorganisms. 2024 Nov 22:12(12):. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12122395. Epub 2024 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 39770599]

Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, Johnston CM, Muzny CA, Park I, Reno H, Zenilman JM, Bolan GA. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2021 Jul 23:70(4):1-187. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1. Epub 2021 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 34292926]

Lanjouw E, Ouburg S, de Vries HJ, Stary A, Radcliffe K, Unemo M. 2015 European guideline on the management of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2016 Apr:27(5):333-48. doi: 10.1177/0956462415618837. Epub 2015 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 26608577]

Martínez-García L, Orviz E, González-Alba JM, Comunión A, Puerta T, Mateo M, Sánchez-Conde M, Rodríguez-Jiménez MC, Rodríguez-Domínguez M, Bru-Gorraiz FJ, Del Romero J, Cantón R, Galán JC. Rapid expansion of lymphogranuloma venereum infections with fast diversification and spread of Chlamydia trachomatis L genovariants. Microbiology spectrum. 2024 Jan 11:12(1):e0285523. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02855-23. Epub 2023 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 38095475]

Ishizuka K, Ohira Y. Lymphogranuloma Venereum. The American journal of medicine. 2023 Nov:136(11):e213-e214. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.07.008. Epub 2023 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 37481017]

de Vries HJC, de Barbeyrac B, de Vrieze NHN, Viset JD, White JA, Vall-Mayans M, Unemo M. 2019 European guideline on the management of lymphogranuloma venereum. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2019 Oct:33(10):1821-1828. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15729. Epub 2019 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 31243838]

Saxon C, Hughes G, Ison C, UK LGV Case-Finding Group. Asymptomatic Lymphogranuloma Venereum in Men who Have Sex with Men, United Kingdom. Emerging infectious diseases. 2016 Jan:22(1):112-116. doi: 10.3201/EID2201.141867. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26691688]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBustos R, Kinzel F, Luzoro A, Bobadilla F, Apey L. [Lymphogranuloma venerous genital in men who have sex with men: a non-imported case report in Chile]. Revista chilena de infectologia : organo oficial de la Sociedad Chilena de Infectologia. 2022 Jun:39(3):340-344. doi: 10.4067/s0716-10182022000200340. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36156696]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceProchazka M, Charles H, Allen H, Cole M, Hughes G, Sinka K. Rapid Increase in Lymphogranuloma Venereum among HIV-Negative Men Who Have Sex with Men, England, 2019. Emerging infectious diseases. 2021 Oct:27(10):2695-2699. doi: 10.3201/eid2710.210309. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34545797]

de Vries HJ, Zingoni A, White JA, Ross JD, Kreuter A. 2013 European Guideline on the management of proctitis, proctocolitis and enteritis caused by sexually transmissible pathogens. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2014 Jun:25(7):465-74. doi: 10.1177/0956462413516100. Epub 2013 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 24352129]

de Vrieze NHN, Versteeg B, Bruisten SM, van Rooijen MS, van der Helm JJ, de Vries HJC. Low Prevalence of Urethral Lymphogranuloma Venereum Infections Among Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Prospective Observational Study, Sexually Transmitted Infection Clinic in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2017 Sep:44(9):547-550. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000657. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28809772]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePathela P, Blank S, Schillinger JA. Lymphogranuloma venereum: old pathogen, new story. Current infectious disease reports. 2007 Mar:9(2):143-50 [PubMed PMID: 17324352]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Summary of notifiable diseases, United States 1995. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 1996 Oct 25:44(53):1-87 [PubMed PMID: 8926993]

de Vrieze NH, de Vries HJ. Lymphogranuloma venereum among men who have sex with men. An epidemiological and clinical review. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2014 Jun:12(6):697-704. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.901169. Epub 2014 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 24655220]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWaalboer R, van der Snoek EM, van der Meijden WI, Mulder PG, Ossewaarde JM. Analysis of rectal Chlamydia trachomatis serovar distribution including L2 (lymphogranuloma venereum) at the Erasmus MC STI clinic, Rotterdam. Sexually transmitted infections. 2006 Jun:82(3):207-11 [PubMed PMID: 16731669]

Stary G, Stary A. Lymphogranuloma venereum outbreak in Europe. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2008 Nov:6(11):935-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06742.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18992036]

Martí-Pastor M, García de Olalla P, Barberá MJ, Manzardo C, Ocaña I, Knobel H, Gurguí M, Humet V, Vall M, Ribera E, Villar J, Martín G, Sambeat MA, Marco A, Vives A, Alsina M, Miró JM, Caylà JA, HIV Surveillance Group. Epidemiology of infections by HIV, Syphilis, Gonorrhea and Lymphogranuloma Venereum in Barcelona City: a population-based incidence study. BMC public health. 2015 Oct 5:15():1015. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2344-7. Epub 2015 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 26438040]

Dougan S, Evans BG, Elford J. Sexually transmitted infections in Western Europe among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2007 Oct:34(10):783-90 [PubMed PMID: 17495592]

Haar K, Dudareva-Vizule S, Wisplinghoff H, Wisplinghoff F, Sailer A, Jansen K, Henrich B, Marcus U. Lymphogranuloma venereum in men screened for pharyngeal and rectal infection, Germany. Emerging infectious diseases. 2013 Mar:19(3):488-92. doi: 10.3201/eid1903.121028. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23621949]

Brenchley JM, Price DA, Douek DC. HIV disease: fallout from a mucosal catastrophe? Nature immunology. 2006 Mar:7(3):235-9 [PubMed PMID: 16482171]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan Nieuwkoop C, Gooskens J, Smit VT, Claas EC, van Hogezand RA, Kroes AC, Kroon FP. Lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis: mucosal T cell immunity of the rectum associated with chlamydial clearance and clinical recovery. Gut. 2007 Oct:56(10):1476-7 [PubMed PMID: 17872578]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRawla P, Thandra KC, Limaiem F. Lymphogranuloma Venereum. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30726047]

Chen JC, Stephens RS. Trachoma and LGV biovars of Chlamydia trachomatis share the same glycosaminoglycan-dependent mechanism for infection of eukaryotic cells. Molecular microbiology. 1994 Feb:11(3):501-7 [PubMed PMID: 8152374]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWhite J, O'Farrell N, Daniels D, British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. 2013 UK National Guideline for the management of lymphogranuloma venereum: Clinical Effectiveness Group of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (CEG/BASHH) Guideline development group. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2013 Aug:24(8):593-601. doi: 10.1177/0956462413482811. Epub 2013 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 23970591]

Soni S, Srirajaskanthan R, Lucas SB, Alexander S, Wong T, White JA. Lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis masquerading as inflammatory bowel disease in 12 homosexual men. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2010 Jul:32(1):59-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04313.x. Epub 2010 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 20345500]

Nieuwenhuis RF, Ossewaarde JM, Götz HM, Dees J, Thio HB, Thomeer MG, den Hollander JC, Neumann MH, van der Meijden WI. Resurgence of lymphogranuloma venereum in Western Europe: an outbreak of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar l2 proctitis in The Netherlands among men who have sex with men. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2004 Oct 1:39(7):996-1003 [PubMed PMID: 15472852]

Roest RW, van der Meijden WI, European Branch of the International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infection and the European Office of the World Health Organization. European guideline for the management of tropical genito-ulcerative diseases. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2001 Oct:12 Suppl 3():78-83 [PubMed PMID: 11589803]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNair PS, Nanda KG, Jayapalan S. The "sign of groove", a new cutaneous sign of internal malignancy. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2007 Mar-Apr:73(2):141 [PubMed PMID: 17460825]

Goens JL, Schwartz RA, De Wolf K. Mucocutaneous manifestations of chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum and granuloma inguinale. American family physician. 1994 Feb 1:49(2):415-8, 423-5 [PubMed PMID: 8304262]

Pendle S, Gowers A. Reactive arthritis associated with proctitis due to Chlamydia trachomatis serovar L2b. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2012 Jan:39(1):79-80. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318235b256. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22183852]

Kober C, Richardson D, Bell C, Walker-Bone K. Acute seronegative polyarthritis associated with lymphogranuloma venereum infection in a patient with prevalent HIV infection. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2011 Jan:22(1):59-60. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010262. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21364072]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKoley S, Mandal RK. Saxophone penis after unilateral inguinal bubo of lymphogranuloma venereum. Indian journal of sexually transmitted diseases and AIDS. 2013 Jul:34(2):149-51. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.120575. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24339471]

Van der Bij AK, Spaargaren J, Morré SA, Fennema HS, Mindel A, Coutinho RA, de Vries HJ. Diagnostic and clinical implications of anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum in men who have sex with men: a retrospective case-control study. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006 Jan 15:42(2):186-94 [PubMed PMID: 16355328]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePinsk I, Saloojee N, Friedlich M. Lymphogranuloma venereum as a cause of rectal stricture. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie. 2007 Dec:50(6):E31-2 [PubMed PMID: 18067700]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIlyas S, Richmond D, Burns G, Bowden KE, Workowski K, Kersh EN, Chandrasekar PH. Orolabial Lymphogranuloma Venereum, Michigan, USA. Emerging infectious diseases. 2019 Nov:25(11):2112-2114. doi: 10.3201/eid2511.190819. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31625852]

Kersh EN, Pillay A, de Voux A, Chen C. Laboratory Processes for Confirmation of Lymphogranuloma Venereum Infection During a 2015 Investigation of a Cluster of Cases in the United States. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2017 Nov:44(11):691-694. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000667. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28876314]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMeyer T. Diagnostic Procedures to Detect Chlamydia trachomatis Infections. Microorganisms. 2016 Aug 5:4(3):. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms4030025. Epub 2016 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 27681919]

Morton AN, Fairley CK, Zaia AM, Chen MY. Anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum in a Melbourne man. Sexual health. 2006 Sep:3(3):189-90 [PubMed PMID: 17044226]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCusini M, Boneschi V, Arancio L, Ramoni S, Venegoni L, Gaiani F, de Vries HJ. Lymphogranuloma venereum: the Italian experience. Sexually transmitted infections. 2009 Jun:85(3):171-2. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.032862. Epub 2008 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 19036777]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSrivastava P, Prasad D. Isothermal nucleic acid amplification and its uses in modern diagnostic technologies. 3 Biotech. 2023 Jun:13(6):200. doi: 10.1007/s13205-023-03628-6. Epub 2023 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 37215369]

Walker GT, Linn CP, Nadeau JG. DNA detection by strand displacement amplification and fluorescence polarization with signal enhancement using a DNA binding protein. Nucleic acids research. 1996 Jan 15:24(2):348-53 [PubMed PMID: 8628661]

Gorzalski AJ, Tian H, Laverdure C, Morzunov S, Verma SC, VanHooser S, Pandori MW. High-Throughput Transcription-mediated amplification on the Hologic Panther is a highly sensitive method of detection for SARS-CoV-2. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2020 Aug:129():104501. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104501. Epub 2020 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 32619959]

Pasternack R, Vuorinen P, Miettinen A. Comparison of a transcription-mediated amplification assay and polymerase chain reaction for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in first-void urine. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 1999 Feb:18(2):142-4 [PubMed PMID: 10219580]

Khehra N, Padda IS, Swift CJ. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 36943981]

Bachmann LH, Johnson RE, Cheng H, Markowitz L, Papp JR, Palella FJ Jr, Hook EW 3rd. Nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis rectal infections. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2010 May:48(5):1827-32. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02398-09. Epub 2010 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 20335410]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae--2014. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2014 Mar 14:63(RR-02):1-19 [PubMed PMID: 24622331]

de Vries HJC, Nori AV, Kiellberg Larsen H, Kreuter A, Padovese V, Pallawela S, Vall-Mayans M, Ross J. 2021 European Guideline on the management of proctitis, proctocolitis and enteritis caused by sexually transmissible pathogens. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2021 Jul:35(7):1434-1443. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17269. Epub 2021 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 34057249]

Bauwens JE, Orlander H, Gomez MP, Lampe M, Morse S, Stamm WE, Cone R, Ashley R, Swenson P, Holmes KK. Epidemic Lymphogranuloma venereum during epidemics of crack cocaine use and HIV infection in the Bahamas. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2002 May:29(5):253-9 [PubMed PMID: 11984440]

Hazra A, Collison MW, Davis AM. CDC Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. JAMA. 2022 Mar 1:327(9):870-871. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1246. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35230409]

Coelho R, Ribeiro T, Abreu N, Gonçalves R, Macedo G. Infectious proctitis: what every gastroenterologist needs to know. Annals of gastroenterology. 2023 May-Jun:36(3):275-286. doi: 10.20524/aog.2023.0799. Epub 2023 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 37144018]

Pathela P, Jamison K, Kornblum J, Quinlan T, Halse TA, Schillinger JA. Lymphogranuloma Venereum: An Increasingly Common Anorectal Infection Among Men Who Have Sex With Men Attending New York City Sexual Health Clinics. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2019 Feb:46(2):e14-e17. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000921. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30278027]

Morré SA, Spaargaren J, Fennema JS, de Vries HJ, Coutinho RA, Peña AS. Real-time polymerase chain reaction to diagnose lymphogranuloma venereum. Emerging infectious diseases. 2005 Aug:11(8):1311-2 [PubMed PMID: 16110579]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCraxford L, Fox A. Lymphogranuloma venereum: a rare and forgotten cause of rectal stricture formation. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2018 Nov:29(11):1133-1135. doi: 10.1177/0956462418773224. Epub 2018 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 29749879]

Bancil AS, Alexakis C, Pollok R. Delayed diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum-associated colitis in a man first suspected to have rectal cancer. JRSM open. 2016 Jan:8(1):2054270416660933. doi: 10.1177/2054270416660933. Epub 2016 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 28203380]

Pimentel R, Correia C, Estorninho J, Gravito-Soares E, Gravito-Soares M, Figueiredo P. Lymphogranuloma Venereum-Associated Proctitis Mimicking a Malignant Rectal Neoplasia: Searching for Diagnosis. GE Portuguese journal of gastroenterology. 2022 Jul:29(4):267-272. doi: 10.1159/000516011. Epub 2021 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 35979244]

He X, Madhav S, Hutchinson L, Meng X, Fischer A, Dresser K, Yang M. Prevalence of Chlamydia infection detected by immunohistochemistry in patients with anorectal ulcer and granulation tissue. Human pathology. 2024 Feb:144():8-14. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2023.12.009. Epub 2023 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 38159868]

Høie S, Knudsen LS, Gerstoft J. Lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis: a differential diagnose to inflammatory bowel disease. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2011 Apr:46(4):503-10. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.537681. Epub 2010 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 21114426]

Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2015 Dec:12(12):720-7. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150. Epub 2015 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 26323879]

Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Dec 23:390(10114):2769-2778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0. Epub 2017 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 29050646]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSigle GW, Kim R. Sexually transmitted proctitis. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2015 Jun:28(2):70-8. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1547334. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26034402]

Santos AL, Coelho R, Silva M, Rios E, Macedo G. Infectious proctitis: a necessary differential diagnosis in ulcerative colitis. International journal of colorectal disease. 2019 Feb:34(2):359-362. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3185-5. Epub 2018 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 30402768]

Lamb CA, Lamb EI, Mansfield JC, Sankar KN. Sexually transmitted infections manifesting as proctitis. Frontline gastroenterology. 2013 Jan:4(1):32-40 [PubMed PMID: 23914292]

Chi KH, de Voux A, Morris M, Katz SS, Pillay A, Danavall D, Bowden KE, Gaynor AM, Kersh EN. Detection of Lymphogranuloma Venereum-Associated Chlamydia trachomatis L2 Serovars in Remnant Rectal Specimens Collected from 7 US Public Health Laboratories. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2022 Jan 1:49(1):e26-e28. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001483. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34075001]

Cole MJ, Field N, Pitt R, Amato-Gauci AJ, Begovac J, French PD, Keše D, Klavs I, Zidovec Lepej S, Pöcher K, Stary A, Schalk H, Spiteri G, Hughes G. Substantial underdiagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum in men who have sex with men in Europe: preliminary findings from a multicentre surveillance pilot. Sexually transmitted infections. 2020 Mar:96(2):137-142. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2019-053972. Epub 2019 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 31235527]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePeuchant O, Laurier-Nadalié C, Albucher L, Balcon C, Dolzy A, Hénin N, Touati A, Bébéar C, Anachla study group. Anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum among men who have sex with men: a 3-year nationwide survey, France, 2020 to 2022. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2024 May:29(19):. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.19.2300520. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38726697]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWorkowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2015 Jun 5:64(RR-03):1-137 [PubMed PMID: 26042815]

Leeyaphan C, Ong JJ, Chow EP, Kong FY, Hocking JS, Bissessor M, Fairley CK, Chen M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Doxycycline Efficacy for Rectal Lymphogranuloma Venereum in Men Who Have Sex with Men. Emerging infectious diseases. 2016 Oct:22(10):1778-84. doi: 10.3201/eid2210.160986. Epub 2016 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 27513890]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencede Vries HJ, Smelov V, Middelburg JG, Pleijster J, Speksnijder AG, Morré SA. Delayed microbial cure of lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis with doxycycline treatment. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009 Mar 1:48(5):e53-6. doi: 10.1086/597011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19191633]

Oud EV, de Vrieze NH, de Meij A, de Vries HJ. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and management of inguinal lymphogranuloma venereum: important lessons from a case series. Sexually transmitted infections. 2014 Jun:90(4):279-82. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051427. Epub 2014 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 24787368]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWard H, Martin I, Macdonald N, Alexander S, Simms I, Fenton K, French P, Dean G, Ison C. Lymphogranuloma venereum in the United kingdom. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007 Jan 1:44(1):26-32 [PubMed PMID: 17143811]

. National guideline for the management of lymphogranuloma venereum. Clinical Effectiveness Group (Association of Genitourinary Medicine and the Medical Society for the Study of Venereal Diseases). Sexually transmitted infections. 1999 Aug:75 Suppl 1():S40-2 [PubMed PMID: 10616382]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence. Drugs for sexually transmitted infections. The Medical letter on drugs and therapeutics. 2017 Jul 3:59(1524):105-112 [PubMed PMID: 28686575]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Vries HJ, Morré SA, White JA, Moi H. European guideline for the management of lymphogranuloma venereum, 2010. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2010 Aug:21(8):533-6. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010238. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20975083]

Blanco JL, Fuertes I, Bosch J, De Lazzari E, Gonzalez-Cordón A, Vergara A, Blanco-Arevalo A, Mayans J, Inciarte A, Estrach T, Martinez E, Cranston RD, Gatell JM, Alsina-Gibert M. Effective Treatment of Lymphogranuloma venereum Proctitis With Azithromycin. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2021 Aug 16:73(4):614-620. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab044. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33462582]

Bilinska J, Artykov R, White J. Effective Treatment of Lymphogranuloma Venereum With a 7-Day Course of Doxycycline. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2024 Jul 1:51(7):504-507. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001963. Epub 2024 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 38465962]

Oda G, Chung J, Lucero-Obusan C, Holodniy M. Clinically Defined Lymphogranuloma Venereum among US Veterans with Human Immunodeficiency Virus, 2016-2023. Microorganisms. 2024 Jun 29:12(7):. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12071327. Epub 2024 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 39065095]

Elgalib A, Alexander S, Tong CY, White JA. Seven days of doxycycline is an effective treatment for asymptomatic rectal Chlamydia trachomatis infection. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2011 Aug:22(8):474-7. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2011.011134. Epub 2011 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 21764781]

Hughes Y, Chen MY, Fairley CK, Hocking JS, Williamson D, Ong JJ, De Petra V, Chow EPF. Universal lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) testing of rectal chlamydia in men who have sex with men and detection of asymptomatic LGV. Sexually transmitted infections. 2022 Dec:98(8):582-585. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2021-055368. Epub 2022 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 35217591]

Cross R, Ling C, Day NP, McGready R, Paris DH. Revisiting doxycycline in pregnancy and early childhood--time to rebuild its reputation? Expert opinion on drug safety. 2016:15(3):367-82. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2016.1133584. Epub 2016 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 26680308]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWormser GP, Wormser RP, Strle F, Myers R, Cunha BA. How safe is doxycycline for young children or for pregnant or breastfeeding women? Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. 2019 Mar:93(3):238-242. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2018.09.015. Epub 2018 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 30442509]