Introduction

Infection with the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) most often occurs in childhood and spreads through airborne, droplet, and contact transmission. Herpes zoster results from reactivation of latent VZV within a sensory nerve ganglion, often presenting decades after the initial infection. The disease typically manifests as a unilateral maculopapular or vesicular rash in a single dermatomal distribution. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) occurs when the virus involves the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal cranial nerve. Although the diagnosis of HZO does not necessarily indicate ocular involvement, eye disease develops in approximately 50% of cases. Ocular manifestations may include conjunctivitis, uveitis, episcleritis, keratitis, and retinitis. Because of the high risk of vision loss if not promptly recognized and treated, HZO is considered an ophthalmologic emergency.[1][2][3]

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus represents one of the most clinically significant forms of VZV reactivation, potentially devastatingly affecting the eye and visual system. Accounting for approximately 10% to 25% of all herpes zoster cases, HZO results from reactivation of dormant VZV in the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve and produces a wide range of cutaneous, ocular, and neurologic complications. Unlike herpes zoster confined to other dermatomes, HZO carries a disproportionately high morbidity, with both acute and chronic sequelae such as keratitis, uveitis, retinitis, optic neuropathy, and postherpetic neuralgia. The clinical burden of HZO extends beyond visual impairment to include chronic pain, diminished quality of life, and substantial socioeconomic consequences for patients and healthcare systems.[4]

Globally, the incidence of herpes zoster increases with advancing age and immunosuppression, paralleling demographic shifts toward aging populations and higher prevalence of chronic diseases. In this context, HZO represents a growing public health concern. Epidemiological study results indicate that the lifetime risk of herpes zoster is nearly 30%, with approximately 1 in 3 individuals expected to develop shingles during their lifetime. Among these, nearly one-quarter will experience ophthalmic involvement, translating into millions of individuals at risk for HZO-related complications worldwide. Immunosenescence, HIV infection, malignancy, and immunosuppressive therapies further amplify susceptibility. Notably, while HZO predominantly affects older adults, cases are increasingly reported in younger, immunocompromised populations, underscoring its broad clinical relevance.[5]

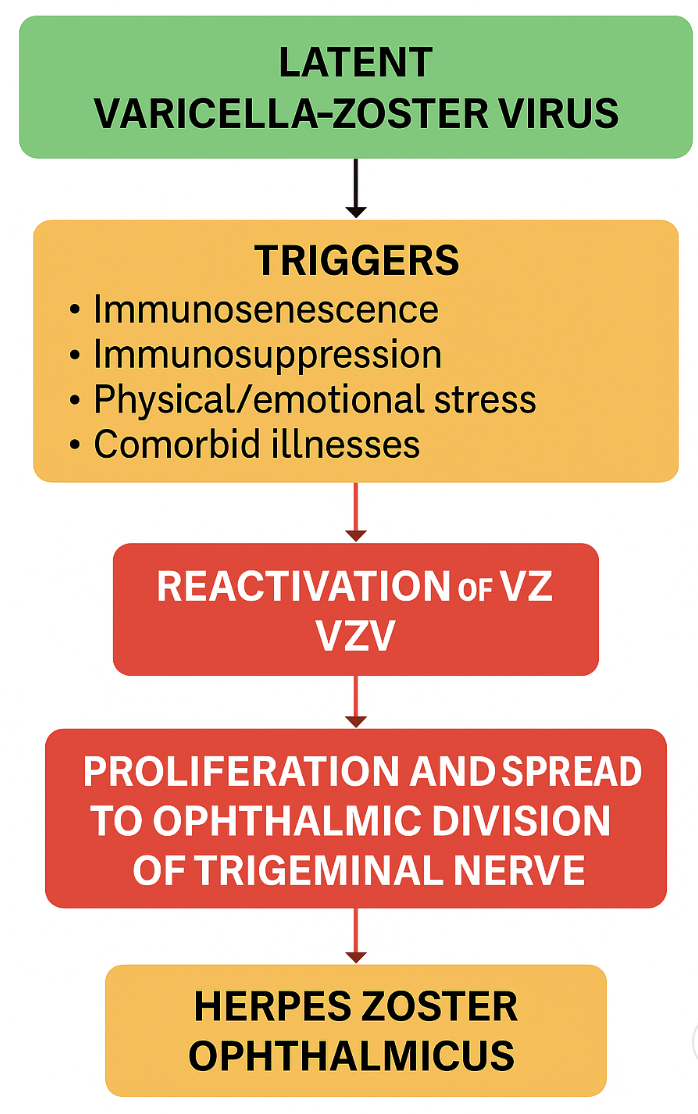

The pathophysiology of HZO reflects the complex interplay between viral latency, immune dysfunction, and neurotropism. Following primary varicella infection, VZV establishes latency in sensory ganglia, including the trigeminal ganglion. Reactivation occurs when cell-mediated immunity wanes, allowing the virus to replicate and travel to the ophthalmic dermatome along sensory axons. Clinically, this manifests as a painful vesicular rash over the forehead, eyelids, and nose (eg, the Hutchinson sign), often preceding or coinciding with ocular involvement (see Image. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus With Hutchinson Sign). Viral replication and subsequent inflammation within ocular tissues can produce keratitis, conjunctivitis, scleritis, or uveitis. In severe cases, posterior segment involvement such as acute retinal necrosis or optic neuritis may occur, threatening irreversible vision loss.[6]

A defining feature of HZO is the broad spectrum of ocular complications. Corneal involvement is widespread, occurring in up to 65% of patients, and includes epithelial keratitis, stromal keratitis, and neurotrophic keratopathy. Chronic inflammation and scarring may lead to corneal opacification, thinning, and perforation. Anterior uveitis, often granulomatous, is another hallmark, which can be complicated by secondary glaucoma and cataract formation. Posterior segment complications, although less common, are vision-threatening and include necrotizing retinitis and vasculitis. Moreover, chronic corneal anesthesia and tear film dysfunction predispose patients to persistent epithelial defects and secondary infections, further compounding morbidity.[7]

Beyond ocular pathology, HZO is strongly associated with postherpetic neuralgia, a chronic neuropathic pain syndrome resulting from VZV-induced damage to sensory nerves. PHN can persist for months to years, significantly impairing quality of life. The combination of vision loss and chronic pain creates a dual burden, with profound psychosocial and economic consequences. Patients with HZO often experience reduced productivity, higher healthcare utilization, and increased risk of depression and social isolation.[8]

Despite advances in antiviral therapy, significant practice gaps persist in the timely recognition and management of HZO. Early initiation of systemic antiviral agents such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir—ideally within 72 hours of rash onset—is critical to limit viral replication, reduce ocular complications, and mitigate the risk of PHN. However, delayed presentation, misdiagnosis, and inconsistent adherence to treatment guidelines remain common. Furthermore, management of HZO often requires long-term surveillance and multidisciplinary input, including ophthalmologists, dermatologists, neurologists, and pain specialists. In many settings, fragmented care and a lack of interprofessional collaboration hinder optimal outcomes.[9]

Vaccination represents a significant advance in the prevention of herpes zoster and HZO. The recombinant zoster vaccine has demonstrated over 90% efficacy in preventing shingles and its complications, even in older adults. Despite this, vaccine uptake remains suboptimal in many regions due to cost, access barriers, and lack of awareness. Expanding immunization coverage could substantially reduce the incidence of HZO and its associated complications, yet strategies for implementation require coordination between public health agencies, clinicians, and policymakers.[10]

Emerging research continues to shed light on the immunological and molecular underpinnings of HZO. Advances in ocular imaging, such as anterior segment optical coherence tomography and in vivo confocal microscopy, are improving the detection and monitoring of corneal and anterior segment changes. Ongoing studies explore novel antivirals, immunomodulatory therapies, and regenerative approaches for neurotrophic keratopathy. The integration of these innovations into clinical practice has the potential to transform the management paradigm for HZO.[11]

From an educational standpoint, a pressing need remains to bridge the gap between evidence-based best practices and real-world clinical care. Clinicians must be equipped to recognize the early signs of HZO and implement comprehensive management strategies that address both acute and chronic sequelae. Continuing education activities are critical in disseminating current evidence, fostering interprofessional collaboration, and enhancing clinician confidence in managing this complex condition.[12]

This educational activity provides participants a thorough overview of herpes zoster ophthalmicus, including its epidemiology, risk factors, clinical features, complications, and management strategies. Learners gain insights into the importance of early antiviral therapy, adjunctive corticosteroid use, and methods for preventing and managing long-term complications such as neurotrophic keratopathy and postherpetic neuralgia. The activity also emphasizes the value of an interprofessional approach, highlighting how collaboration among ophthalmologists, primary care clinicians, dermatologists, neurologists, pharmacists, and pain specialists enhances patient care.

Ultimately, this educational activity aims to equip clinicians with the knowledge and skills to improve patient outcomes in HZO. By addressing current practice gaps, fostering interprofessional collaboration, and integrating emerging evidence into practice, this activity will help reduce the burden of vision loss and chronic pain associated with HZO. As the population ages and the incidence of herpes zoster rises, the need for effective education and training in managing HZO becomes ever more critical.[13]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

In those with a history of prior infection, the VZV normally lies dormant within a dorsal root ganglion. In a healthy individual, immunity acquired from the initial infection allows suppression of the virus. However, often in weakened immunity, the virus may reactivate in the form of herpes zoster, also known as shingles. HZO specifically refers to a reactivated VZV infection involving the V1 nerve division after having lain dormant within the trigeminal nerve ganglion (also known as the Gasserian ganglion). V1 is subdivided into 3 branches: the frontal nerve branch, the nasociliary nerve branch, and the lacrimal nerve branch. Any or all of these nerve branches may be affected by HZO (see Image. The disease typically results in ocular and facial lesions with potential progression to more serious complications. The main risk factors for HZO include being aged 50 years or older and having an immunocompromised status (eg, history of HIV, autoimmune diseases requiring corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants, organ or bone marrow transplant, or chemotherapy treatment). Other chronic diseases, acute illnesses, and physical and emotional stressors can also precipitate HZO.[2][3]

HZO is caused by reactivation of latent VZV, a human neurotropic α-herpesvirus belonging to the Herpesviridae family. After primary infection with varicella (eg, chickenpox), the virus establishes latency in cranial nerves, dorsal roots, and autonomic ganglia. Specifically, in HZO, the virus lies dormant in the trigeminal ganglion and, upon reactivation, spreads along the ophthalmic division (eg, V1) of the trigeminal nerve.[4]

Triggers of Reactivation

Reactivation occurs when cell-mediated immunity against VZV declines. Several host and environmental factors contribute to this process:

- Aging (immunosenescence): The most substantial risk factor is the progressive decline in T-cell function with age; most cases occur after 50 years.

- Immunosuppression: Conditions such as HIV infection, hematological malignancies, organ transplantation, and long-term corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy significantly increase the risk.

- Stress and systemic illness: Physical or emotional stress, trauma, and intercurrent illness can alter immune surveillance and precipitate viral reactivation.

- Vaccination gaps: In populations with low uptake of varicella or zoster vaccines, the risk of reactivation and complications remains higher.[5]

Pathophysiology of Ocular Involvement

Once reactivated, VZV replicates and travels along sensory axons to the ophthalmic dermatome, producing the classic painful vesicular rash on the forehead, eyelid, and nose. Viral particles and immune-mediated inflammation extend into ocular tissues, where they can cause:

- Conjunctivitis and episcleritis (early involvement)

- Keratitis (epithelial, stromal, or neurotrophic) due to direct viral cytopathy and immune response

- Anterior uveitis from viral antigen-induced inflammation

- Retinitis, optic neuritis, and vasculitis in severe or disseminated cases [6]

Why Ophthalmic Involvement Occurs

The trigeminal nerve's ophthalmic division (V1) has extensive sensory innervation of the cornea, conjunctiva, sclera, iris, and eyelids. Viral reactivation within this distribution explains the high frequency of ocular manifestations. The Hutchinson sign—vesicles on the tip or side of the nose—indicates nasociliary nerve involvement and correlates with a higher likelihood of ocular complications.[6]

Epidemiology

In the United States, herpes zoster affects about 1 per 1000 individuals annually. However, in those aged 60 and older, the incidence is closer to 1 per 100 individuals. The incidence in older adults is lower in those who have received live attenuated or inactivated recombinant zoster vaccines. Among patients diagnosed with herpes zoster, some epidemiological studies estimate that about 8 to 20% are complicated by HZO, with many of those cases resulting in ocular involvement.[2][14][15][16] HZO accounts for approximately 10% to 25% of all herpes zoster cases, making it one of the most frequent and clinically significant reactivation sites. The epidemiology of HZO reflects the global distribution of VZV and population trends such as aging, immunosuppression, and vaccination practices.[4]

Global Burden

Worldwide, the incidence of herpes zoster is estimated at 3 to 5 cases per 1000 person-years, with rates increasing sharply in older populations to over 10 cases per 1000 person-years in individuals aged 60 years and older; approximately 10% to 20% of these manifest as HZO, equating to millions of cases annually. With global increases in life expectancy and a higher prevalence of immunosuppressive conditions, the burden of HZO is expected to rise significantly in the coming decades.[17]

United States

In the United States, the incidence of herpes zoster is approximately 3.5 to 4.5 per 1000 person-years, with HZO making up about 8% to 20% of cases. Recent epidemiological data suggest increased HZO incidence, even after introducing zoster vaccines, particularly in older adults. Studies report that HZO is most prevalent in individuals aged 50 years and older, although younger individuals with HIV/AIDS, malignancies, or immunosuppressive therapy are also at risk.[4]

Sex Distribution

Most population-based studies show a slightly higher incidence in females than males, mirroring trends in herpes zoster more broadly. This difference may reflect both immunological and healthcare-seeking factors. However, no strong sex predilection is consistently observed in all cohorts.[5]

Risk across age groups

- Children and adolescents: Rare, typically seen in those with perinatal varicella infection or congenital immunodeficiencies.

- Young adults: Relatively uncommon but associated with HIV or immunosuppressive therapy.

- Middle-aged and older adults: Incidence rises steeply in those aged 50 and older, with peak risk beyond age 70. Immunosenescence plays a central role in this age-related increase.[18]

Trends in the Vaccination Era

The introduction of the live attenuated zoster vaccine (Zostavax) and later the recombinant subunit vaccine (Shingrix) has markedly reduced the overall incidence of herpes zoster and HZO in vaccinated cohorts. However, incomplete uptake, cost barriers, and reduced efficacy in immunocompromised individuals limit the full preventive potential. In unvaccinated or high-risk populations, HZO remains a significant cause of vision-threatening disease.[19]

In summary, HZO is a global ophthalmic and neurological health concern, disproportionately affecting older adults and immunocompromised individuals. The disease contributes significantly to vision loss, chronic pain, and healthcare utilization worldwide. With rising life expectancy and persisting challenges in vaccine uptake, the epidemiological burden of HZO is projected to increase, highlighting the need for vigilant clinical recognition, preventive strategies, and interprofessional care.[20]

Pathophysiology

HZO follows the typical pathogenic process of herpes zoster. VZV is a double-stranded DNA virus that initially invades the upper respiratory tract via virus-laden respiratory droplets, replicating and invading adjacent lymph nodes. After about a week, the virus disseminates and progresses to a secondary cutaneous infection, with vesicle eruption occurring several days later. Following the primary infection, the virus follows a retrograde pathway along axons toward sensory nerve ganglia, where it enters the latent phase. The virus moves anterograde toward superficial tissue in the reactivation phase, reemerging as herpes zoster.[21]

HZO develops from the reactivation of latent VZV that persists in the trigeminal ganglion following primary varicella infection (chickenpox). After latency, when cell-mediated immunity declines due to aging, immunosuppression, or stress, the virus reactivates and spreads centrifugally along the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve, reaching the skin, cornea, conjunctiva, and ocular adnexa.[22] See Image. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus, Pathophysiology.

Neurotropism and Viral Spread

- The ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve provides sensory innervation to the cornea, conjunctiva, sclera, iris, eyelids, and forehead. Viral reactivation in this distribution explains the dermatomal rash and high frequency of ocular manifestations.

- Viral replication in the affected nerves causes neuritis, leading to acute pain and neuralgia. Inflammatory mediators and immune cell infiltration further contribute to nerve injury, predisposing to chronic postherpetic neuralgia.[23]

Ocular Tissue Involvement

- Cornea: Direct viral replication and immune-mediated responses cause epithelial, stromal, and disciform keratitis and eventual neurotrophic keratopathy due to sensory nerve damage.

- Uvea: Anterior uveitis occurs when viral antigens stimulate an immune reaction, which can be complicated by secondary glaucoma and cataract formation.

- Sclera/episclera: Episcleritis and scleritis are less common but can present with persistent pain and inflammation.

- Posterior segment: In severe cases, HZO causes acute retinal necrosis, optic neuritis, and retinal vasculitis, leading to irreversible vision loss.[19]

Host Immune Response

The pathogenesis is partly due to viral cytopathic effects and partly to host immune-mediated injury. Inflammatory cytokines, T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity, and vascular inflammation all contribute to tissue damage, explaining why ocular complications may persist even after active viral replication subsides.[24]

Most Common Clinical Findings

- A painful vesicular rash in the V1 dermatome (forehead, upper eyelid, nose tip—Hutchinson sign) is common.

- Ocular involvement occurs in ~50–70% of cases, most commonly keratitis and anterior uveitis.

- Long-term sequelae include corneal scarring, chronic uveitis, neurotrophic keratopathy, glaucoma, cataract, and postherpetic neuralgia.[25]

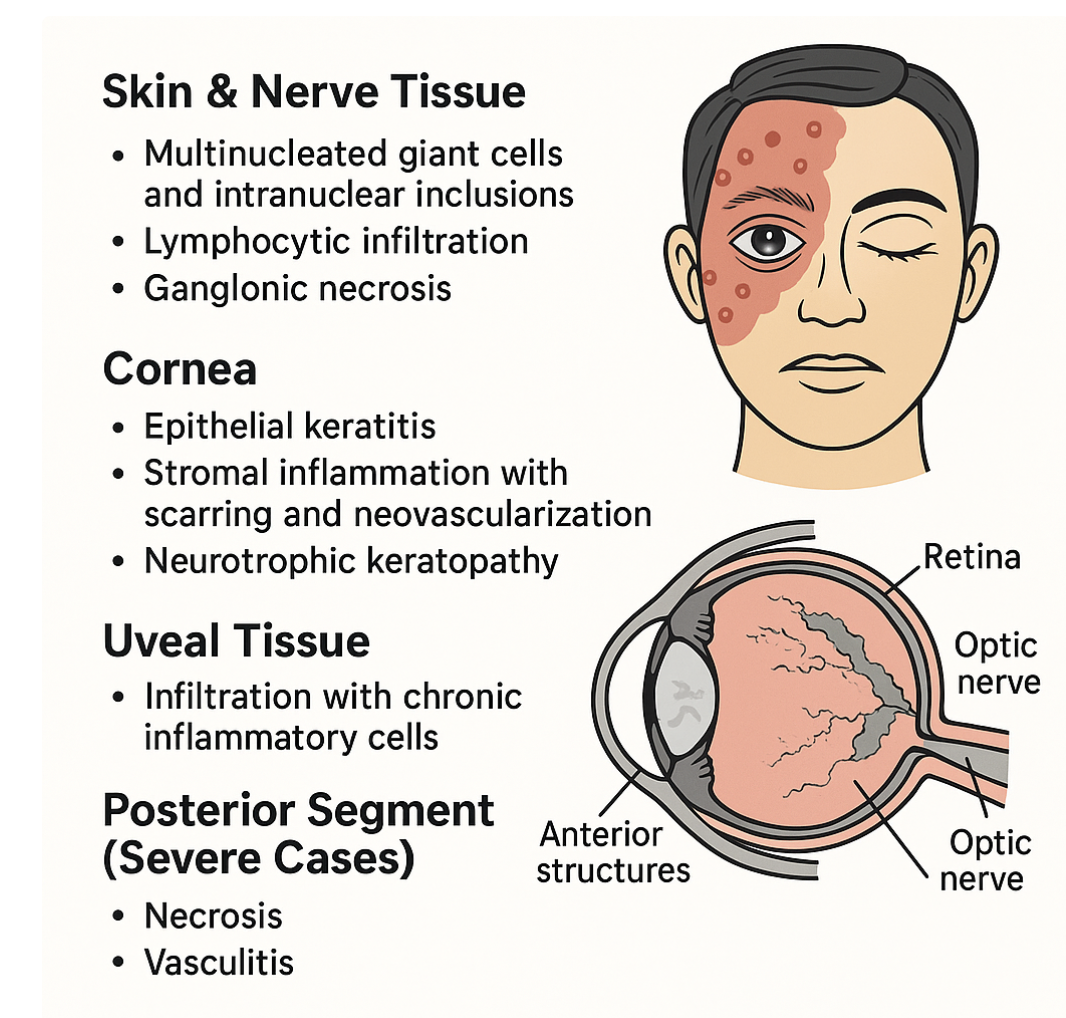

Histopathology

Microscopic examination of tissues affected by HZO reveals a spectrum of changes reflecting viral cytopathic effects, immune-mediated inflammation, and tissue degeneration. These changes vary depending on whether skin, cornea, uveal tissue, or nerves are examined.[18] See Image. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus, Histopathology.

Skin and Nerve Tissue

- Epidermis: In vesicular lesions, the epidermis shows ballooning degeneration, multinucleated giant cells, and intranuclear eosinophilic inclusions (Cowdry type A), typical of herpesvirus infections.

- Dermis and nerves: Viral replication causes lymphocytic infiltration, edema, and necrosis of sensory ganglia, with degeneration of axons and demyelination of affected nerves. Chronic inflammatory changes explain the persistence of postherpetic neuralgia.[26]

Cornea

- Epithelial keratitis: Viral cytopathic changes include necrosis, intraepithelial inclusion bodies, and epithelial cell loss, leading to punctate keratitis.

- Stromal keratitis: Histology demonstrates stromal infiltration with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages, along with edema, collagen disorganization, and neovascularization. Chronic inflammation leads to stromal scarring and thinning.

- Neurotrophic keratopathy: Nerve density is markedly reduced, with loss of corneal sensory fibers, contributing to impaired epithelial healing and persistent epithelial defects.[27]

Uveal Tissue

- Anterior uveitis: The iris and ciliary body show dense lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration, vascular endothelial swelling, and fibrin and pigmented cell deposition in the anterior chamber. Chronic uveitis may result in posterior synechiae and secondary glaucoma.[18]

Posterior Segment (Severe Cases)

- Retina: Acute retinal necrosis demonstrates full-thickness retinal necrosis, perivascular inflammation, and occlusive vasculitis.

- Optic nerve: Optic neuritis associated with HZO shows axonal degeneration, gliosis, and lymphocytic infiltration.[26]

Key Histopathological Features

- Multinucleated giant cells and intranuclear inclusions in epithelial tissue

- Lymphocytic infiltration and ganglionic necrosis in sensory nerves

- Corneal stromal inflammation with scarring and neovascularization

- Uveal tissue infiltration with chronic inflammatory cells

- Posterior segment necrosis and vasculitis in advanced cases [25]

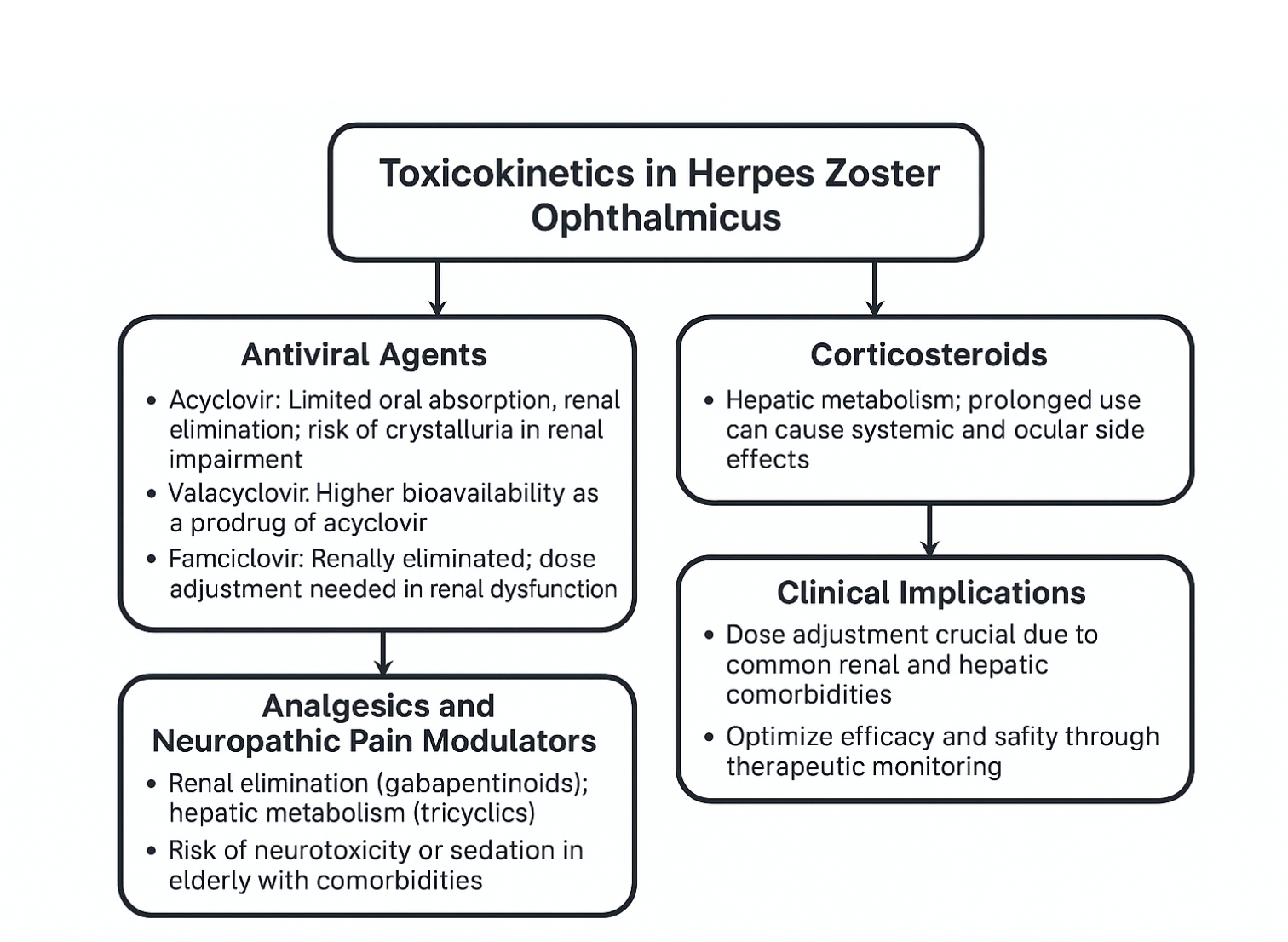

Toxicokinetics

Although HZO itself is a viral reactivation syndrome rather than a toxin-mediated disease, the concept of toxicokinetics becomes clinically relevant in the context of antiviral and adjunctive pharmacotherapy, since the safety, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of these agents significantly influence outcomes.[28] See Image. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus, Toxicokinetics.

Antiviral Agents

- Acyclovir: Administered orally or intravenously, acyclovir undergoes limited oral absorption (bioavailability ~10%–20%) and is widely distributed in extracellular fluids, including ocular tissues. This drug is primarily eliminated via the kidneys through glomerular filtration and tubular secretion. In renal impairment, toxic accumulation can cause crystalluria, nephropathy, and neurotoxicity.

- Valacyclovir: A prodrug of acyclovir with 3 to 5 times greater bioavailability, allowing higher systemic exposure and improved ocular penetration. This drug's metabolism occurs via first-pass intestinal and hepatic hydrolysis to acyclovir, followed by renal excretion.

- Famciclovir: This oral prodrug, rapidly converted to penciclovir, offers high oral bioavailability (~77%) and is renally eliminated. Dose adjustment is required in renal dysfunction to prevent toxicity.[29]

Corticosteroids

Systemic or topical corticosteroids are sometimes used as adjunct therapy in severe HZO with uveitis or scleritis. Their pharmacokinetics involve hepatic metabolism and renal excretion of inactive metabolites. Toxicologically, prolonged exposure can lead to systemic complications such as hyperglycemia, osteoporosis, immunosuppression, and ocular adverse effects, including glaucoma and cataract.[23]

Analgesics and Neuropathic Pain Modulators

Agents like gabapentin, pregabalin, or tricyclic antidepressants are used for postherpetic neuralgia. Their toxicokinetics highlight renal elimination (gabapentinoids) or hepatic metabolism (tricyclics), necessitating careful dosing in elderly or multi-morbid patients to avoid neurotoxicity, sedation, or cardiotoxicity.[26]

Clinical Implications

Understanding the toxicokinetics of these drugs is critical in HZO management, especially since many patients are older adults with comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease or diabetes. Inadequate dose adjustment increases the risk of systemic toxicity, while underdosing may allow viral persistence and ocular damage. Optimized dosing strategies, therapeutic monitoring, and multidisciplinary coordination are essential for balancing efficacy and safety in HZO therapy.[19]

History and Physical

Patients with HZO typically present with prodromal pain in a unilateral V1 dermatomal distribution, followed by an erythematous vesicular or pustular rash to the same area. Pain is neuropathic, and patients may describe the sensation as "burning" or "shooting," sometimes accompanied by paresthesias. Additionally, the herpetic rash may be preceded by constitutional symptoms such as fever, fatigue, malaise, and headaches. The presence of herpetic lesions around the tip of the nose is known as the Hutchinson sign. The presence of the Hutchinson sign indicates nasociliary branch involvement of V1, which confers a higher risk for ocular involvement. The nasociliary branch innervates the tip of the nose, cornea, and other ocular structures.[30][31][32][33][34][35]

The physical exam begins with an external evaluation of lesion distribution, including the eyelids and scalp. The rash often appears maculopapular before transitioning to vesicles and pustules that ultimately rupture and scab over. Although the rash is usually limited to a single unilateral dermatome, immunocompromised individuals may develop disseminated disease, with a possible bilateral presentation. Particular attention should be paid to eyelid involvement, which is frequently associated with blepharitis, conjunctivitis, and episcleritis. Ptosis is rare but may occur in response to marked inflammation. A thorough ocular exam must include visual acuity, slit-lamp examination with fluorescein staining, and ocular tonometry; a thorough dilated funduscopic exam is also necessary.[23]

- Corneal involvement includes both epithelial keratitis and stromal keratitis.

- Epithelial keratitis may present as punctate and/or pseudodendritic keratitis. Scattered fluorescein-stained swollen lesions on the superficial surface of the cornea characterize punctate keratitis. These lesions may contain the live replicating virus. Pseudodendrites appear as branching lesions similar to the true dendritic lesions in herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis. Unlike the dendrites of HSV, which appear as brightly staining ulcers with terminal bulbs, HZO pseudodendrites are non-erosive mucous plaques that exhibit minimal staining without terminal bulbs.[4]

- Stromal keratitis may be classified as anterior or deep and usually develops after epithelial keratitis. Anterior stromal keratitis results from an immune-mediated response to the virus and is characterized by nummular (coin-shaped) granules in the superficial stroma. Deep stromal keratitis usually occurs late in the disease course (often months after the acute phase) and presents with marked corneal edema, often associated with anterior uveitis.[29]

- Severe keratitis may lead to neurotrophic keratopathy due to persistent inflammatory injury to the corneal sensory nerves. Assessing corneal sensation can help evaluate for peripheral nerve damage.[24]

- Uveitis may be categorized as anterior, posterior, or panuveitis.

- On slit-lamp examination, anterior uveitis is visualized as floating leukocytes and proteins from vascular damage, commonly referred to as "cell and flare."

- Posterior uveitis presents as leukocytes floating in the vitreous cavity (vitritis) or as areas of retinal whitening representing inflammation and necrosis in severe cases. Optic neuritis may be an associated finding as well.[36]

- Every patient with HZO should undergo ocular tonometry to evaluate for elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). Elevated IOP due to HZO usually occurs secondary to zoster-induced trabeculitis. However, it may also occur due to obstruction of the trabecular meshwork from the inflammatory cells, protein debris, or synechiae formation due to extensive intraocular inflammation. Prolonged elevation in IOP may lead to secondary glaucoma.[37]

Patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus typically report a prodrome of systemic and neurological symptoms, followed by the onset of a painful rash:

- Prodromal Phase (2–5 days before rash): Patients may experience malaise, fatigue, low-grade fever, and headache. Neurologic symptoms include burning, tingling, or shooting pain localized to the ophthalmic dermatome (forehead, scalp, upper eyelid, and side of the nose). This pain often precedes the rash and can be severe enough to prompt early medical attention.[25]

- Acute Phase: Patients develop a painful vesicular eruption over the V1 dermatome within days. Vesicles on the tip of the nose (eg, the Hutchinson sign) indicate nasociliary nerve involvement and strongly predict ocular complications.[22]

- Ocular Symptoms: Patients often complain of red eye, blurred vision, photophobia, tearing, and foreign body sensation. Severe cases may present with decreased vision, diplopia, or ocular pain associated with keratitis, uveitis, or scleritis.

- Neuropathic Sequelae: Some patients describe persistent pain even after rash resolution, which is characteristic of postherpetic neuralgia.[19]

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination reveals the following findings:

- Skin: Unilateral, dermatomal vesicular rash over the forehead, periorbital skin, upper eyelid, and nose. The rash progresses from erythematous macules → papules → vesicles → pustules → crusts. Swelling of the eyelid and periorbital edema may accompany severe cutaneous disease.[18]

- Eye (ocular findings):

- Conjunctiva: Conjunctivitis with hyperemia, chemosis, or mucopurulent discharge

- Cornea: Punctate epithelial keratitis, dendriform lesions (distinguishable from HSV dendrites by their tapered ends and lack of terminal bulbs), stromal keratitis, and neurotrophic keratopathy in later stages [6]

- Anterior segment: Granulomatous anterior uveitis with keratic precipitates, hypopyon (rare), posterior synechiae, and elevated intraocular pressure due to trabeculitis

- Sclera/episclera: Episcleritis or diffuse/nodular scleritis [22]

- Posterior segment (severe cases): Retinitis, acute retinal necrosis, retinal vasculitis, and optic neuritis.

- Neurological: Cranial nerve palsies (III, IV, VI) may occur due to vasculitis or orbital apex inflammation, resulting in ophthalmoplegia and diplopia.[38]

Key Findings to Document

- Dermatomal distribution of rash (always unilateral, respecting the midline)

- Presence of the Hutchinson sign (predictor of ocular involvement)

- Visual acuity measurement and intraocular pressure

- Detailed slit-lamp examination (cornea, anterior chamber, iris, lens)

- Dilated fundus examination (rule out posterior segment involvement) [39]

Evaluation

HZO is primarily a clinical diagnosis based on history and classic findings from physical and slit-lamp examinations. Additional procedures, such as ocular tonometry and corneal esthesiometry, may be performed for a more thorough evaluation to assess for complications. Other diagnostic tests, such as viral cultures, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and antibody testing, are rarely required to establish a diagnosis of HZO. For patients with disseminated herpes zoster (disease involving multiple dermatomes), severe illness, or those with significant risk factors, it is reasonable to consider HIV testing. Additional laboratory tests and imaging are seldom warranted.[40][41]

Evaluation of Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus

Clinical diagnosis

- History and examination remain the cornerstone of evaluation. Key features include dermatomal vesicular rash involving the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, acute ocular pain, and prodromal symptoms.

- Ocular examination: Slit-lamp biomicroscopy is essential to assess for conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis, episcleritis/scleritis, and secondary glaucoma. Corneal sensation should be tested because neurotrophic keratopathy is common.[22]

Laboratory tests

- PCR: Highly sensitive and specific for VZV DNA in aqueous humor or vesicle fluid. This is recommended for atypical presentations or immunocompromised patients.

- Direct fluorescent antibody testing: This detects VZV antigens in skin scrapings or conjunctival samples but is less commonly performed in routine practice.

- Serology; VZV immunoglobulin (Ig) M/IgG: This has a limited role in acute diagnosis; more useful for epidemiology or immune status determination.

- Complete blood count and renal/liver function tests: Test at baseline before systemic antivirals, especially in older adults and immunocompromised individuals.[23]

Imaging studies

- Orbital and cranial imaging: CT/MRI are indicated when orbital cellulitis, intracranial spread, or vasculopathy is suspected. MRI angiography may be required in cases with neurological symptoms to rule out stroke related to VZV vasculitis.

- Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT)/confocal microscopy: These are useful in research or refractory cases to assess the corneal nerve plexus and keratopathy.[18]

Ophthalmic ancillary tests

- Corneal sensitivity testing: Important for detecting neurotrophic keratopathy

- Tonometry: To detect secondary glaucoma due to trabeculitis or uveitis

- Fundus examination and OCT: To rule out acute retinal necrosis, progressive outer retinal necrosis, or vasculitis

- Fluorescein Angiography: Occasionally needed in cases of retinal involvement or ischemic optic neuropathy [42]

Special Situations

- Immunocompromised individuals (HIV, transplant, chemotherapy): Additional evaluation with HIV serology, CD4 counts, or immunosuppressive profile is recommended.

- Neurological assessment: Lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid PCR for VZV if suspected of meningitis, encephalitis, or vasculitis.[43]

National and International Guidelines

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO):

- Early initiation of systemic antivirals (within 72 hours of rash onset).

- Comprehensive slit-lamp evaluation to monitor keratitis, uveitis, and IOP.

- Ophthalmic follow-up to detect late sequelae (neurotrophic keratopathy, glaucoma, cataract).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, USA):

- Laboratory confirmation is rarely needed; clinical diagnosis is standard.

- Antivirals are recommended for all immunocompromised patients and those ≥50 years.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, UK):

- Antivirals (acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) should be prescribed promptly in suspected HZO regardless of age.

- Referral to ophthalmology is mandatory if ocular involvement is suspected.

- Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR, India):

- Emphasizes early ophthalmic referral, aggressive antiviral therapy, and multidisciplinary management in immunocompromised patients.[4]

Follow-Up and Monitoring

- Short-term (daily to weekly): Monitoring epithelial, stromal keratitis, and uveitis

- Long-term (monthly to yearly): Evaluation for late complications such as neurotrophic keratopathy, secondary glaucoma, cataract, post-herpetic neuralgia, and retinal involvement [29]

Treatment / Management

Treatment for HZO includes prompt initiation of antiviral agents for all patients and supportive care for symptom management. Other adjunct therapies, such as antibiotics, topical or systemic corticosteroids, and corneal epithelial debridement, are considered case-by-case.[44][45][46][47](A1)

- Supportive care: Artificial tears, cold compresses, and analgesics may be employed.

- Antiviral agents: Ideally, treatment with systemic antiviral agents should begin within 72 hours of disease onset. Initiation should not be delayed while awaiting definitive diagnosis or ophthalmology follow-up. Topical antiviral agents may be considered, but there is limited evidence regarding their utility in managing HZO.[4]

- Immunocompetent adult dosing (choose single agent):

- Acyclovir 800 mg orally 5 times per day for at least 7 days

- Valacyclovir 1000 mg orally every 8 hours for at least 7 days (may require renal dosing)

- Famciclovir 500 mg orally 3 times per day for at least 7 days (may require renal dosing)

- Immunocompromised adult dosing (choose a single agent):

- Acyclovir 10 mg/kg of ideal body weight intravenously (IV) every 8 hours for at least 7 days

- Foscarnet 90 mg/kg IV every 12 hours (typically reserved for severe or acyclovir-resistant disease) [9]

- Immunocompetent adult dosing (choose single agent):

- Antibiotics: Topical antibiotics (eg, erythromycin ophthalmic ointment) are often administered to help prevent secondary bacterial infection.[29]

- Corticosteroids: Both topical and systemic corticosteroids may be used in disease management. Systemic corticosteroids, including HZO, are often used to treat herpes zoster. However, clinical trial results have shown variable results, and the potential for adverse events must be weighed against any potential benefit. The timing and extent to which topical corticosteroids are used are determined through ophthalmology consultation. Manifestations treated with topical corticosteroids include stromal keratitis, uveitis, and trabeculitis.[18]

- Topical aqueous suppressants: These agents are commonly used in combination with topical corticosteroids to treat elevated IOP secondary to HZO.

- Debridement: Ophthalmology may consider debridement in cases of epithelial keratitis.[7] (B2)

General Principles

Management of HZO aims to:

- Reduce viral replication

- Prevent ocular complications

- Manage inflammation and pain

- Prevent long-term sequelae such as neurotrophic keratopathy and post-herpetic neuralgia.[23]

Antiviral therapy (first-line)

- Oral antivirals (initiate within 72 hours of rash onset):

- Acyclovir 800 mg 5 times daily × 7 to 10 days

- Valacyclovir 1000 mg 3 times daily × 7 days

- Famciclovir 500 mg 3 times daily × 7 days

- IV Acyclovir (10–15 mg/kg every 8 hours × 7–10 days) is recommended in:

- Immunocompromised individuals

- Disseminated disease

- Central nervous system or orbital involvement

- Duration: Most guidelines recommend 7 to 10 days, but longer therapy may be needed in immunocompromised individuals.[23]

Ocular management

- Conjunctivitis/Episcleritis: Lubricants ± mild topical steroids

- Epithelial Keratitis: Usually self-limited; preservative-free lubricants; avoid topical steroids unless stromal involvement

- Stromal Keratitis/Uveitis:

- Topical corticosteroids (eg, prednisolone acetate 1%) with gradual taper are recommended.

- Cycloplegics (atropine/homatropine) for pain and synechiae prevention.[6]

- Neurotrophic Keratopathy:

- Lubricants, autologous serum drops, and therapeutic contact lenses

- Severe cases: Amniotic membrane graft or tarsorrhaphy

- Elevated IOP/Glaucoma:

- Topical anti-glaucoma agents (avoid prostaglandin analogs if uveitic component) [48]

- Retinal Necrosis (acute retinal necrosis, progressive outer retinal necrosis)

- IV acyclovir or oral valacyclovir at a high dose is recommended.

- Intravitreal ganciclovir/foscarnet may be added.

- Prompt retinal consultation.[49]

Pain and post-herpetic neuralgia management

- Acute Pain: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or opioids if severe.

- Post-herpetic neuralgia:

- First-line: Gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, nortriptyline)

- Topical agents: Lidocaine patches, capsaicin cream

- Interventional: Nerve blocks in refractory cases [50]

Adjunctive therapies

- Systemic corticosteroids:

- Controversial; may reduce acute pain and speed rash healing when combined with antivirals

- Not routinely recommended by AAO/CDC unless severe inflammation or orbital involvement

- Lubrication: Preservative-free artificial tears are essential to prevent exposure keratopathy.[5]

Surgical interventions

- Tarsorrhaphy/amniotic membrane transplant: For severe neurotrophic keratopathy or non-healing epithelial defects

- Keratoplasty: Reserved for corneal scarring and perforations

- Cataract/glaucoma surgery: May be required as a late sequela of recurrent inflammation [51]

National and International Guidelines

- AAO Preferred Practice Pattern:

- Initiate systemic antivirals within 72 hours.

- Ophthalmology referral is mandatory for suspected ocular involvement.

- Long-term follow-up is recommended for keratopathy, glaucoma, and postherpetic neuralgia.

- CDC (USA):

- Antivirals for all adults ≥50 years and immunocompromised patients

- Zoster vaccine recommended for prevention (Shingrix preferred)

- NICE (UK):

- Early antiviral therapy (acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir)

- Analgesics and neuropathic pain agents for postherpetic neuralgia

- Referral to ophthalmology for eye involvement

- ICMR (India):

- Emphasis is on early referral, antiviral therapy, and judicious use of topical steroids.

- Vaccination is encouraged in the elderly and high-risk populations.[52]

Prevention

- Recombinant Zoster Vaccine (Shingrix):

- 90% effective in preventing herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia

- Recommended for adults ≥50 years and immunocompromised individuals ≥18 years

- Live Attenuated Vaccine (Zostavax):

- Less effective and not preferred when Shingrix is available

HZO treatment is centered on prompt antiviral therapy, ocular management with steroids and lubricants as indicated, IOP control, management of neurotrophic keratopathy and postherpetic neuralgia, and surgical intervention for complications. AAO, CDC, NICE, and ICMR guidelines universally stress early initiation of antivirals and ophthalmic referral as the cornerstone of care.[53]

Differential Diagnosis

HZO presents with a unilateral, dermatomal vesicular eruption involving the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve, often with ocular complications. Several conditions can mimic its cutaneous, ocular, or systemic manifestations, and accurate differentiation is critical for timely antiviral therapy and prevention of complications (see Table. Differential Diagnosis of HZO and Mimickers).

Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

- Cutaneous herpes simplex virus, HSV: This condition may present with grouped vesicles, pain, and erythema on the face or eyelids. Unlike HZO, HSV lesions are not dermatomal and may recur in the same or different locations.

- Ocular HSV:

- Epithelial keratitis: Dendritic ulcers resemble zoster pseudodendrites; differ by having terminal bulbs and true ulceration (zoster lesions are raised without bulbs)

- Stromal keratitis: Immune-mediated, often recurrent

- Uveitis: HSV uveitis can mimic HZO-related uveitis; tends to affect younger individuals [54]

Bacterial Skin Infections

- Impetigo:

- Caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes

- Honey-colored crusts, not dermatomal, are typically seen in children

- Cellulitis/periorbital cellulitis:

- Presents with erythema, edema, and tenderness

- No vesicular lesions or dermatomal restriction

- Orbital Cellulitis:

- May mimic orbital involvement in HZO (proptosis, pain, restricted motility)

- Confirmed by CT/MRI imaging; lacks vesicular rash [55]

Contact Dermatitis

- Triggered by allergens (cosmetics, topical medications)

- Presents with erythema, itching, scaling, and vesicles

- Bilateral or patchy distribution; improves after allergen avoidance

- Unlike HZO, pain is absent, and the dermatomal pattern is lacking [56]

Blepharitis and Other Lid Disorders

- Chronic lid margin inflammation may mimic early HZO redness and edema.

- Absence of vesicular rash, dermatomal distribution, and systemic symptoms helps differentiate.[54]

Other Viral Exanthems

- Varicella (chickenpox):

- Generalized vesicular rash in crops, often with systemic prodrome.

- In children, varicella may involve the eyelids but is not restricted to the trigeminal dermatome.

- Molluscum contagiosum:

- Umbilicated papules on eyelid skin, mistaken for healed zoster vesicles.[57]

Autoimmune and Inflammatory Conditions

- Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis:

- Diffuse vesiculobullous eruptions, mucosal involvement, systemic illness

- Unlike HZO, not dermatomal and usually drug-related

- Erythema multiforme:

- Target lesions on the skin may involve the ocular surface

- Precipitated by HSV or drugs, but lacks dermatomal restriction

- Discoid lupus erythematosus:

- Chronic erythematous plaques with scaling on the face; no acute vesicles [58]

Ophthalmic Masquerades

- Acute angle-closure glaucoma:

- Pain, redness, corneal edema, decreased vision

- May mimic the painful red eye of HZO, but lacks rash

- Scleritis/episcleritis:

- Painful, red eye; mistaken for ocular zoster involvement

- No vesicles or skin lesions

- Endophthalmitis:

- Severe pain, vision loss, hypopyon, but no dermatomal rash [59]

Neurological Conditions

- Trigeminal neuralgia:

- Severe unilateral facial pain in the trigeminal distribution

- No skin rash or ocular involvement

- May precede HZO rash (zoster sine herpete), making differentiation difficult

- Migraine with ophthalmoplegia:

- Periorbital pain and ocular motor palsy; no vesicular rash [30]

Zoster Sine Herpete

- A unique diagnostic dilemma where VZV reactivation occurs without rash.

- This presents as trigeminal neuralgia–like pain with ocular involvement.

- This requires PCR confirmation from aqueous humor or CSF.[60]

Key Distinguishing Features

Table. Differential Diagnosis of HZO and Mimickers

|

HSV, herpes simplex virus; HZO, herpes zoster ophthalmicus; IOP, intraocular pressure; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis |

The main differentials for HZO include HSV infection, bacterial skin infections, contact dermatitis, autoimmune dermatoses, and neurological pain syndromes. Careful assessment of rash morphology, dermatomal distribution, ocular involvement, and systemic features, supplemented with PCR testing when required, is essential to avoid misdiagnosis and prevent sight-threatening complications.

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Early Systemic Antivirals (acute zoster)

- Valacyclovir vs acyclovir (Randomized controlled trial [RCT], n=1141): Valacyclovir (7–14 days) shortened time to resolution of zoster-associated pain vs acyclovir (median 38–44 vs 51 days) and reduced persistent pain at 6 months (19.3% vs 25.7%). Supports the use of high-bioavailability agents within 72 hours.[61] See Table. Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials in Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus

- Famciclovir vs placebo (RCT, n=419): Accelerated lesion healing and decreased duration of postherpetic neuralgia. Rationale for famciclovir as an acceptable alternative when started promptly.[62]

- Acyclovir ± prednisolone; 7 vs 21 days (NEJM RCT): 21 days offered no benefit over 7 days; adding a short prednisolone taper improved acute pain/function but did not reduce postherpetic neuralgia—explains why routine systemic steroids are selective rather than universal.[63]

Ocular Disease Control (Keratitis/Iritis) and Suppression

- Zoster Eye Disease Study (ZEDS; multicenter RCT): One-year low-dose valacyclovir in immunocompetent HZO individuals reduced multiple disease flare-ups and new/worsening ocular disease at 18 months in secondary analyses; trial protocol NCT03134196 (completed 2024). Provides rationale for considering suppressive therapy in recurrent HZO.[36]

- The primary postherpetic neuralgia endpoint is not superior overall, though some prespecified subgroups showed reduced pain and medication needs; the ocular outcomes paper reports the effects of the suppression strategy (see abstracts). Use to guide shared decision-making when contemplating 12-month suppression.[64]

Retinal Complications (Acute Retinal Necrosis/Progressive Outer Retinal Necrosis)

- Systemic antivirals + intravitreal therapy: Best available evidence (level II/III) supports combining systemic acyclovir/valacyclovir with intravitreal foscarnet or ganciclovir to reduce progression and fellow-eye involvement. No head-to-head RCTs; guidance informed by retrospective series and consensus.[64]

Vaccination for Preventing HZO and Postherpetic Neuralgia

- Recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix) pivotal Phase III trials—ZOE-50 and ZOE-70: Efficacy against herpes zoster ~97% (in those 50–69 years) and significant reduction in zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in those aged 70 and older; underpins guideline recommendations to vaccinate adults 50 and older, and immunocompromised individuals 18 and older when appropriate.[65]

Guideline Anchors

Why we recommend early antivirals + ophthalmic referral:

- AAO/NICE/consensus: Initiate oral antivirals within 72 h of rash onset; refer urgently for any eye involvement; tailor topical steroids/cycloplegics to stromal disease/uveitis; monitor intraocular pressure. These synthesize the RCT data above into practice.[66]

Ongoing/Recently Completed Trial(s)

- ZEDS (NCT03134196): Multicenter, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled; 12-month valacyclovir suppression after recent HZO keratitis/iritis. Completed 2024; publications emerging in 2025 (ocular outcomes and postherpetic neuralgia analyses). Use results to individualize suppression for patients with recurrent or chronic HZO.[36]

How this evidence supports our recommendations

- Start high-bioavailability antivirals early → RCTs show faster pain resolution and less prolonged pain vs older regimens [67]

- Reserve systemic steroids for select cases → Acute symptom benefit without postherpetic neuralgia reduction; avoid routine use without clear indication[68]

- Consider suppressive valacyclovir in recurrent HZO keratitis/iritis → ZEDS signals fewer flares on longer-term follow-up; discuss benefits/uncertainties with patients [36]

- Vaccinate eligible adults → Robust Phase III data justify strong preventive recommendations [69]

- For acute retinal necrosis and progressive outer retinal necrosis → Combine systemic + intravitreal antivirals per best available nonrandomized controlled trial evidence [6]

Table. Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials in Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus

|

Study/Trial |

Design/n |

Key Outcomes |

Implications for Practice |

|

Valacyclovir vs Acyclovir RCT |

Randomized Controlled Trial, n=1141 |

Valacyclovir shortened pain duration vs acyclovir; less persistent pain at 6 months |

High-bioavailability antivirals preferred for HZO |

|

Famciclovir vs Placebo RCT |

Randomized Controlled Trial, n=419 |

Famciclovir reduced lesion healing time and post-herpetic neuralgia duration |

Famciclovir is a valid oral alternative |

|

Acyclovir ± Prednisolone RCT (NEJM) |

Randomized Controlled Trial, multicenter |

No benefit of 21 d vs 7 d; steroids improved acute symptoms, but no PHN prevention |

Steroids selective, not routine; antivirals mandatory |

|

ZEDS (Zoster Eye Disease Study) |

Multicenter RCT, >500 patients (NCT03134196) |

1-yr valacyclovir reduced recurrent keratitis/iritis; mixed PHN benefit in subgroups |

Consider long-term suppression in recurrent ocular HZO |

|

ARN/PORN Retrospective Series |

Case series/cohort studies |

Systemic + intravitreal antivirals slowed progression; reduced fellow-eye involvement |

Combine systemic + intravitreal therapy for retinal necrosis |

|

ZOE-50 and ZOE-70 (Shingrix Trials) |

Phase III RCTs, >30,000 participants |

Shingrix efficacy ~97% in 50–69 y; significantly reduced zoster and PHN in ≥70 y |

Strong basis for adult zoster vaccination recommendations |

HZO, herpes zoster ophthalmicus; NEJM, New England Journal of Medicine; PHN, postherpetic neuralgia; RCT, randomized controlled trial

Treatment Planning

Effective treatment planning for HZO requires a stepwise, multidisciplinary approach to halting viral replication, managing ocular inflammation, alleviating pain, preventing complications, and ensuring long-term rehabilitation. Planning should be individualized based on disease severity, immune status, age, and systemic comorbidities.[5]

Immediate/Early Phase (First 72 hours)

- Initiate systemic antiviral therapy promptly:

- Acyclovir 800 mg by mouth 5×/day, Valacyclovir 1000 mg 3x/day, or famciclovir 500 mg 3x/day (7–10 days).

- IV acyclovir for immunocompromised or severe orbital/neurological disease.

- Pain control with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or short-course opioids.

- Referral to an ophthalmologist at the earliest suspicion of ocular involvement.

- Baseline investigations (renal/liver function tests, complete blood count) to guide safe antiviral dosing.[4]

Acute Ocular Disease Management

- Epithelial keratitis: Lubricants; avoid topical steroids

- Stromal keratitis/uveitis:

- Topical corticosteroids (eg, prednisolone acetate 1%) with slow taper

- Cycloplegics (atropine/homatropine)

- Intraocular pressure control: Topical anti-glaucoma drugs (except prostaglandin analogs)

- Neurotrophic keratopathy:

- Lubricants, serum tears, therapeutic contact lenses

- Severe cases: Amniotic membrane grafting or tarsorrhaphy

- Retinal necrosis: Systemic + intravitreal antivirals, urgent retina consult [9]

Pain and Neuralgia Planning

- Acute pain: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, short opioids

- Post-herpetic neuralgia: Gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants, topical lidocaine patches

- Refractory cases: Pain specialist referral, nerve blocks [37]

Intermediate/Maintenance Phase

- Monitor weekly during acute inflammation: Slit-lamp, intraocular pressure checks, corneal status

- Consider prophylactic antiviral suppression:

- ZEDS results show low-dose valacyclovir (500 mg daily) may reduce recurrent keratitis/uveitis in select patients.

- Steroid tapering plan: Prevent rebound uveitis; avoid premature withdrawal [36]

Long-Term/Preventive Phase

- Monitor for sequelae: Cataract, secondary glaucoma, neurotrophic keratopathy, chronic uveitis

- Vaccination planning:

- Recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix) is recommended for adults aged 50 and older or immunocompromised ≥18 years, ideally administered after acute episode resolution.

- Rehabilitation:

- Low-vision aids for patients with residual corneal scarring or optic neuropathy

- Psychological support for patients with chronic pain [53]

Multidisciplinary Planning

- Ophthalmology: Cornea, glaucoma, and retina specialists for targeted care

- Neurology: For VZV vasculitis, cranial neuropathies, encephalitis

- Infectious Diseases/Immunology: For immunocompromised individuals

- Pain Medicine: For chronic postherpetic neuralgia [6]

Treatment planning in HZO is time-sensitive and layered: initiate antivirals early, manage acute ocular inflammation, plan for pain control and long-term monitoring, and consider prophylactic antivirals and vaccination. A multidisciplinary approach ensures optimal outcomes and reduces the risk of vision-threatening complications.[70]

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Treatment of HZO primarily involves systemic antivirals, topical corticosteroids, cycloplegics, analgesics, and, in selected cases, systemic corticosteroids or adjunctive agents. While highly effective, these therapies can lead to systemic and ocular toxicities that require careful monitoring and management.

Antiviral Therapy (Acyclovir, Valacyclovir, Famciclovir)

- Common adverse effects:

- Gastrointestinal: Nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort

- Neurological: Headache, dizziness, fatigue, confusion (especially in older adults)

- Renal toxicity (acyclovir): Crystalluria, nephrotoxicity, and acute kidney injury

- Management:

- Ensure adequate hydration to reduce crystalluria risk.

- Adjust doses in renal impairment according to creatinine clearance.

- Monitor serum creatinine and electrolytes in older adults and immunocompromised individuals.

- If neurotoxicity occurs, a dose reduction or discontinuation is required.[71]

Topical Corticosteroids (Prednisolone Acetate, Dexamethasone)

- Common adverse effects:

- Elevated intraocular pressure → steroid-induced glaucoma.

- Cataract formation with prolonged use.

- Worsening of epithelial keratitis or risk of secondary infection.

- Management:

- Regularly monitor IOP during therapy.

- Use the lowest effective dose with gradual tapering.

- Avoid unsupervised long-term use.

- Add prophylactic lubricants to minimize epithelial compromise.[72]

Systemic Corticosteroids (Prednisone, Prednisolone)

- Adverse effects:

- Short-term: Gastritis, hyperglycemia, mood changes, fluid retention.

- Long-term: Immunosuppression, osteoporosis, adrenal suppression.

- Management:

- Prescribe short courses only when indicated (severe inflammation, orbital involvement).

- Use proton pump inhibitors to reduce gastric irritation.

- Monitor blood sugar and blood pressure in elderly/diabetic/hypertensive patients.

- Avoid in uncontrolled infections.[73]

Cycloplegics (Atropine, Homatropine)

- Adverse effects:

- These include blurred vision, photophobia, dry mouth, and flushing (systemic absorption).

- Rarely, there are central nervous system effects in children (restlessness, hallucinations).

- Management:

- Use the minimal effective dose.

- Avoid in narrow-angle glaucoma.

- Use caution in children and older adults.[74]

Analgesics and Neuropathic Pain Medications

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Gastrointestinal irritation, renal impairment → coprescribe proton pump inhibitors in high-risk individuals

- Opioids: Constipation, drowsiness, dependence risk → limit use to severe pain

- Gabapentin/pregabalin: Dizziness, somnolence, weight gain

- Tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline): Dry mouth, urinary retention, cardiac arrhythmias in older adults

- Management:

- Start with the lowest dose and titrate gradually.

- Monitor for sedation, falls, and cardiac risk in older adults.

- Consider multimodal pain therapy to minimize toxicity from single high-dose drug regimens.[75]

Adjunctive Measures

- Antiglaucoma Medications: Beta-blockers (risk of bradycardia, bronchospasm), carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (electrolyte imbalance)

- Amniotic membrane grafts/surgery: Minimal systemic toxicity; risk limited to surgical complications and infection [76]

Preventive and Monitoring Strategies

- Baseline investigations: Complete blood count, renal/liver function before antivirals and systemic steroids

- Ocular monitoring: Intraocular pressure checks, slit-lamp follow-up, fundus evaluation for necrosis/vasculitis

- Multidisciplinary care: Collaboration with nephrology, internal medicine, and pain specialists for toxicity management

- Vaccination: Recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix) reduces recurrence risk and medication exposure, minimizing drug-related adverse events

Toxicity management in HZO involves anticipating, preventing, and promptly treating adverse effects of antivirals, corticosteroids, and pain medications. Individualized dosing, renal adjustment, regular ocular/systemic monitoring, and interdisciplinary coordination are key to maximizing treatment benefit while minimizing harm.[77]

Staging

Unlike malignancies, HZO does not have a universally accepted tumor, node, metastasis-like staging system. However, clinicians often classify the disease according to clinical phases, ocular involvement, and severity, which helps guide prognosis and management. Below are the main staging approaches:

Clinical Phases of HZO (Dermatologic Progression)

- Prodromal stage

- Duration: 2–5 days before rash

- Features: Burning pain, tingling, hyperesthesia in the trigeminal V1 distribution; headache, malaise, low-grade fever

- No visible skin changes yet

- Acute eruptive stage

- Duration: First 1–2 weeks

- Features: Erythematous macules → papules → vesicles → pustules → crusting

- Dermatomal, unilateral rash along the ophthalmic nerve; Hutchinson’s sign (lesions on the tip/side of the nose) predicts ocular involvement

- Subacute healing stage

- Duration: 2–4 weeks

- Features: Crusts fall off, leaving erythematous or hyperpigmented macules; acute ocular complications (keratitis, uveitis) often manifest

- Chronic/post-herpetic stage

- Beyond 1 month

- Features: Post-herpetic neuralgia, neurotrophic keratopathy, ocular sequelae (cataract, glaucoma, corneal scarring, optic atrophy) [54]

Ocular Involvement–Based Staging

A practical ophthalmology-oriented staging (used in clinical settings):

- Stage I (pre-ocular/cutaneous phase):

- Rash in V1 distribution, no ocular involvement

- Represents early disease—high window for antiviral therapy

- Stage II (anterior segment involvement):

- Conjunctivitis, episcleritis, keratitis (epithelial or stromal), and anterior uveitis

- Most common presentation in referred cases

- Stage III (posterior segment involvement):

- Scleritis, choroiditis, retinitis (acute retinal necrosis, progressive outer retinal necrosis), optic neuritis

- Represents severe disease with a poor prognosis

- Stage IV (chronic/complicated disease):

- Neurotrophic keratopathy, corneal perforation, secondary glaucoma, cataract, postherpetic neuralgia, permanent vision loss [54]

Severity Grading (Proposed in Literature)

Some authors classify HZO severity as:

- Mild: Cutaneous involvement only, no ocular disease

- Moderate: Anterior segment disease, controlled with medical therapy

- Severe: Posterior segment involvement, optic nerve disease, or vision-threatening sequelae [78]

Zoster Sine Herpete (Special Entity)

- Rare variant without rash

- Presents with isolated ocular inflammation or neuralgia

- Considered under stage II–III equivalent, depending on ocular structures affected

Staging of HZO can be approached through clinical phases (prodromal, acute, healing, chronic), or more usefully for ophthalmologists, by ocular involvement stages (cutaneous only → anterior segment → posterior segment → chronic sequelae). This structured staging framework helps determine the urgency of antiviral therapy, the need for topical/systemic steroids, and the intensity of ophthalmic follow-up.[60]

Prognosis

The prognosis of HZO is highly variable and largely dependent on the patient’s risk factors, the timing of treatment, and the aggressiveness of the disease. There is limited data on the morbidity and mortality rates of HZO. However, most immunocompetent individuals with herpes zoster who receive early treatment have a resolution of lesions within four weeks and can be managed on an outpatient basis. The prognosis of HZO depends on the timing of antiviral therapy, the extent of ocular involvement, the host's immune status, and age at presentation. With early recognition and treatment, most patients achieve favorable outcomes; however, a significant subset develops vision-threatening complications and chronic pain syndromes.[4]

Impact of Early Antiviral Therapy

- Favorable outcomes are strongly associated with antiviral initiation within 72 hours of rash onset, leading to faster rash healing, reduced acute pain, and lower incidence of post-herpetic neuralgia.

- Delayed therapy is associated with greater ocular involvement, prolonged pain, and increased risk of complications such as keratitis, uveitis, and retinal necrosis.[29]

Short-Term Prognosis

- Cutaneous lesions usually resolve within 2 to 4 weeks, leaving residual hypo- or hyperpigmentation.

- Ocular prognosis is variable:

- Mild conjunctivitis and superficial keratitis often resolve completely.

- Stromal keratitis and anterior uveitis carry a higher risk of recurrent disease, scarring, and vision loss.

- Posterior involvement (acute retinal necrosis, optic neuritis) often leads to permanent visual impairment despite aggressive therapy.[79]

Long-Term Prognosis

- Chronic/recurrent ocular disease:

- Stromal keratitis and uveitis may persist or recur for months to years, leading to corneal opacification, cataract, and secondary glaucoma.

- Neurotrophic keratopathy can cause persistent epithelial defects and corneal melting.

- Postherpetic neuralgia:

- Affects 20% to 30% of patients overall, and up to 50% of older adult patients (>60 years).

- This condition can be debilitating and resistant to treatment.

- Retinal necrosis syndromes have a poor prognosis; bilateral involvement may occur in up to 35% without prompt systemic and intravitreal antiviral therapy.[18]

Prognostic Factors

- Poor prognosis associated with:

- Older age (>60 years)

- Immunocompromised status (HIV, transplant, chemotherapy)

- Severe initial rash with Hutchinson sign (nasociliary involvement)

- Delayed antiviral therapy (>72 hours)

- Posterior segment involvement (acute retinal necrosis, progressive outer retinal necrosis, optic neuritis)

- Better prognosis:

- Young, immunocompetent individuals with early antiviral therapy and anterior segment–limited disease [71]

Preventive Prognosis (Vaccination)

- The recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix) has shown >90% efficacy in preventing herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia, drastically improving prognosis in vaccinated populations.

- Patients with prior HZO episodes who receive vaccination have lower recurrence rates and reduced severity in subsequent episodes.

The overall prognosis of HZO ranges from benign and self-limiting in early-treated, mild cases to vision- and life-threatening in severe, delayed, or immunocompromised cases. Prompt antiviral therapy, vigilant ophthalmic monitoring, and preventive vaccination are the most significant factors in improving long-term outcomes.[18]

Complications

As discussed in the history and physical section, a thorough examination of the HZO patient may reveal an array of complications, including blepharitis, conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis, and secondary glaucoma. Prolonged inflammation and corneal scarring can lead to serious complications, including permanent vision loss. Neurotrophic keratopathy, resulting from dysfunctional corneal innervation, leaves patients more susceptible to corneal abrasions, ulcers, and persistent corneal epithelial defects, even without replicating viruses or active inflammation. Necrotizing retinitis is an uncommon complication of HZO that can lead to retinal tears, retinal detachment, and subsequent permanent vision changes.

Additionally, patients with HZO commonly develop postherpetic neuralgia as a result of a peripheral nerve injury. Postherpetic neuralgia is a chronic painful condition in which herpes zoster pain persists for over 90 days after the initial rash outbreak. Older age and severe disease are risk factors for postherpetic neuralgia, while prior zoster vaccination appears protective. In addition to complications directly related to HZO, patients are also prone to secondary bacterial infections.[32][33][34][35]

HZO can result in a wide spectrum of complications ranging from cutaneous scarring to severe, sight-threatening, and life-threatening conditions. These complications can be categorized into ocular, neurological, dermatologic, and systemic domains. Their incidence is influenced by patient age, immune status, and the timeliness of antiviral therapy.

Ocular Complications

- Eyelid and adnexal:

- Cicatricial lid deformities (entropion, ectropion, lagophthalmos) [80]

- Chronic blepharitis and madarosis

- Conjunctiva:

- Conjunctivitis, conjunctival scarring, symblepharon formation [81]

- Cornea:

- Epithelial keratitis (dendritiform pseudodendrites)

- Stromal keratitis: Chronic, recurrent condition; leads to scarring and thinning

- Neurotrophic keratopathy: Persistent epithelial defects, corneal melt, perforation

- Lipid keratopathy, infectious keratitis (secondary bacterial/fungal) [82]

- Sclera:

- Episcleritis, scleritis (diffuse or necrotizing)

- Uvea:

- Anterior uveitis (granulomatosa o no granulomatosa)

- Chronic or recurrent uveitis: Secondary glaucoma, cataract [83]

- Retina and optic nerve:

- Acute retinal necrosis

- Progressive outer retinal necrosis (especially in immunocompromised)

- Retinal vasculitis, branch retinal artery occlusion

- Optic neuritis or ischemic optic neuropathy → permanent vision loss [84]

- Glaucoma and cataract:

- Steroid-induced or inflammatory secondary glaucoma

- Cataracts (can result from chronic inflammation or steroid therapy) [85]

Neurological Complications

- Post-herpetic neuralgia:

- Persistent neuropathic pain lasting months to years

- Incidence increases with age (>50% in patients >60 years)

- Cranial nerve palsies:

- Ophthalmoplegia due to CN III, IV, or VI involvement

- Trigeminal neuralgia-like recurrent pain syndromes

- Central nervous system involvement:

- VZV encephalitis, meningitis, and myelitis

- VZV vasculopathy → ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, particularly in older adults and immunocompromised individuals [86]

Dermatological Complications

- Secondary bacterial skin infection (impetiginization, cellulitis)

- Scarring and post-inflammatory pigmentation changes

- Chronic ulceration in immunocompromised patients [87]

Systemic Complications

- In immunocompromised individuals: Disseminated cutaneous zoster, visceral involvement (pneumonitis, hepatitis)

- Psychological complications: Depression, anxiety, reduced quality of life due to chronic pain and vision loss

Long-Term Sequelae

- Vision-threatening conditions include corneal opacity, glaucoma, optic atrophy, and retinal necrosis.

- Pain-related: Debilitating postherpetic neuralgia resistant to therapy

- Functional disability: Loss of binocular vision, scarring deformities, psychosocial impairment

Complications of HZO range from acute inflammatory ocular events to chronic structural and neurological sequelae. Prompt initiation of antiviral therapy and careful ophthalmic monitoring are essential to reduce the burden of long-term morbidity. Vaccination remains the most effective preventive measure to reduce these complications.[88]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

HZO often leads to severe ocular complications requiring medical, surgical, and rehabilitative interventions. Postoperative and rehabilitation care is essential to preserve vision, prevent recurrence, manage chronic pain, and restore quality of life.

Immediate Postoperative Care (After Ocular Surgery)

Surgeries may include tarsorrhaphy, amniotic membrane transplantation, keratoplasty, cataract extraction, or glaucoma procedures in advanced HZO cases.

- Medication regimen:

- Continue systemic antivirals during the perioperative period to reduce viral reactivation risk.

- Topical antibiotics are used to prevent secondary infections.

- Use topical corticosteroids for inflammation control (with close intraocular pressure monitoring).

- Lubricating agents help to protect the ocular surface.

- Monitoring:

- Frequent slit-lamp examination to assess wound healing, epithelial status, and corneal graft clarity

- Intraocular pressure measurement post cataract or glaucoma surgery

- Pain management:

- Adequate analgesia, including neuropathic pain agents when needed [89]

Ocular Surface and Corneal Rehabilitation

- Neurotrophic keratopathy management:

- Long-term use of preservative-free lubricants, autologous serum tears

- Bandage contact lenses or scleral lenses for epithelial protection

- Repeated amniotic membrane transplantation or cenegermin (nerve growth Factor eye drops, where available) for nonhealing defects

- Keratoplasty (penetrating keratoplasty/deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty):

- Regular graft monitoring is necessary to detect rejection or infection

- Prolonged antiviral prophylaxis in high-risk patients [90]

Visual Rehabilitation

- Optical correction:

- Rigid gas-permeable or scleral contact lenses for irregular corneal astigmatism

- Spectacle correction for residual refractive error [91]

- Low vision aids:

- Magnifiers, telescopic lenses, and electronic devices for patients with irreversible corneal scarring or optic neuropathy [92]

- Surgical rehabilitation:

- Secondary keratoplasty or keratoprosthesis (Boston KPro) in end-stage corneal blindness when conventional grafting fails [93]

Pain and Neuralgia Management

- Postherpetic neuralgia:

- Long-term neuropathic pain medications (gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants)

- Topical lidocaine or capsaicin patches

- Referral to pain specialists for nerve blocks, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation therapy, or intrathecal interventions in refractory cases [94]

- Psychological rehabilitation:

- Counseling and mental health support to address depression, anxiety, and reduced quality of life [95]

Systemic and Preventive Care

- Vaccination: Recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix) recommended post-recovery to reduce recurrence risk

- Nutritional support: Adequate hydration and a balanced diet to promote healing and immunity

- Immunocompromised individuals: Closer monitoring and longer antiviral prophylaxis (may be needed) [96]

Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation Team

- Ophthalmology: Cornea, glaucoma, and retina specialists for targeted follow-up

- Neurology/pain medicine: To manage neuralgia and central nervous system complications

- Low-vision specialists: For visual rehabilitation and assistive devices

- Psychology/psychiatry: For coping with chronic pain and vision loss

- Primary care/immunology: To optimize systemic health and vaccination status [97]

Postoperative and rehabilitation care in HZO is multifaceted, involving surgical aftercare, long-term ocular surface management, visual rehabilitation, chronic pain therapy, and psychosocial support. A multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach is key to restoring function, preventing recurrences, and improving quality of life.[98]

Consultations

Managing HZO often requires a multidisciplinary approach due to its potential for multisystem involvement, ocular complications, neurological sequelae, and chronic pain. Timely consultations ensure optimal care, prevention of complications, and long-term rehabilitation.

Ophthalmology Consultation

- Primary and essential referral in all suspected or confirmed cases of HZO with ocular involvement.

- Role includes:

- Comprehensive slit-lamp and fundus evaluation.

- Management of keratitis, uveitis, scleritis, neurotrophic keratopathy, and retinal complications.

- Monitoring for long-term sequelae such as glaucoma, cataract, corneal scarring, and optic neuropathy.

- Subspecialty consultations:

- Cornea Specialist: For persistent keratitis and neurotrophic ulcers

- Glaucoma Specialist: For secondary glaucoma

- Retina Specialist: For acute retinal necrosis, progressive outer retinal necrosis, or vasculitis [30]

Neurology Consultation

- Indicated in patients with:

- Severe or refractory postherpetic neuralgia

- Cranial nerve palsies (III, IV, VI)

- Suspected central nervous system involvement (encephalitis, meningitis, vasculopathy leading to stroke)

- Provides advanced pain management strategies and neuroimaging guidance.[99]

Infectious Disease/Internal Medicine

- For immunocompromised individuals (HIV, transplant, chemotherapy)

- Guidance on systemic antiviral dosing and duration

- Screening for underlying immunodeficiency in atypical or severe presentations

- Coordinating multidisciplinary management in disseminated or recurrent cases [100]

Pain Medicine/Palliative Care

- Consult for management of postherpetic neuralgia unresponsive to first-line medications

- May provide interventional therapies:

- Nerve blocks, spinal injections, or neuromodulation

- Ensures improved quality of life in patients with chronic pain [101]

Dermatology Consultation

- For diagnosis of atypical cutaneous eruptions (differentiating HZO from HSV, dermatitis, bacterial infections)

- Management of secondary bacterial infection or scarring [102]

Psychiatry/Psychology

- Chronic postherpetic neuralgia, visual disability, and disfiguring skin lesions can lead to depression and anxiety.

- Referral for counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy, and psychiatric care improves psychosocial outcomes.[103]

Rehabilitation and Low Vision Services

- For patients with irreversible visual loss due to corneal opacity, retinal necrosis, or optic neuropathy

- Provision of low vision aids, orientation and mobility training, and occupational rehabilitation [104]

Consultations in HZO are not limited to ophthalmology; a multidisciplinary network including neurology, infectious disease, pain medicine, dermatology, psychiatry, and rehabilitation services ensures comprehensive patient care, minimizing both short- and long-term morbidity.[54]

Deterrence and Patient Education

As part of their preventative care guidelines, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends adults aged 50 years and older receive herpes zoster vaccination to lower their risk of viral reactivation. There is 1 vaccine on the market, an inactivated recombinant vaccine. The inactivated vaccine was approved in 2018 and is administered as a 2-dose series. This vaccine has demonstrated 97% efficacy in patients aged 50 to 70 and 90% efficacy in patients older than 70. Patients can still receive the inactivated vaccine despite having previously received the live vaccine.