Vertigo in Clinical Practice: Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Treatment

Vertigo in Clinical Practice: Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Treatment

Introduction

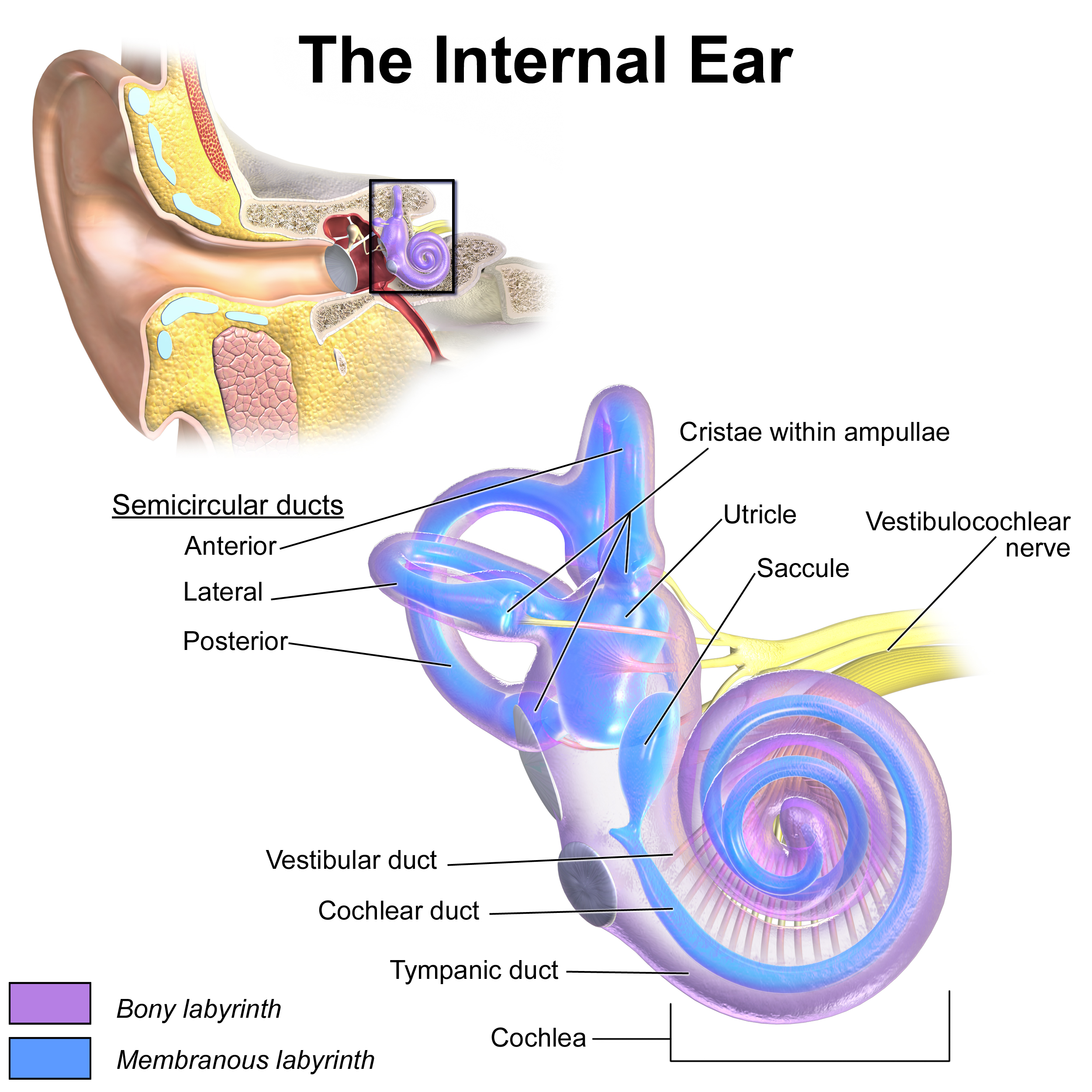

Vertigo is a common complaint encountered in primary care and emergency settings, characterized by a sensation of motion, typically rotational, resulting from vestibular dysfunction. Precise differentiation of vertigo from other types of dizziness, such as presyncope, disequilibrium, or lightheadedness, is crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.[1] This symptom impacts individuals across all age groups. In younger patients, vertigo frequently originates from inner ear pathology. (see Image. Inner Ear Anatomy). In older adult populations, targeted assessment is imperative, as central causes of vertigo—more common among this demographic—elevate the risk of falls and associated complications. This necessitates meticulous evaluation to facilitate appropriate treatment and enhance patient outcomes. [2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Vertigo is most commonly caused by a dysfunction in the vestibular system, whether a peripheral or central lesion.[1] Peripheral etiologies encompass common causes of vertigo, including benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) and Ménière's disease.[3] BPPV arises from displaced calcium carbonate crystals, or otoconia, predominantly within the posterior semicircular canal. This condition manifests as transient, paroxysmal, and recurrent episodes of vertigo, typically lasting only a few minutes or less. These episodes are frequently accompanied by nausea and other associated symptoms, such as vomiting.[1] In contrast to BPPV, patients diagnosed with Ménière disease often present with tinnitus, hearing impairment, and aural fullness alongside vertigo. Endolymphatic hydrops constitutes a characteristic pathological feature of Ménière disease.[4] [5] The symptoms of Ménière disease are caused by an increased volume of endolymph within the semicircular canals. If left untreated, this condition can lead to a progressive loss of hearing.

Two additional distinct causes of peripheral vertigo include acute labyrinthitis and vestibular neuritis. Both originate from inflammation, frequently induced by a preceding or concurrent viral infection.[1] Another viral-induced cause of vertigo is Herpes zoster oticus, also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome.[6] In Ramsay Hunt syndrome, vertigo results from the reactivation of latent Varicella-zoster virus in the geniculate ganglion, which can cause inflammation of the facial and vestibulocochlear nerves; this often leads to rashes, facial paralysis, tinnitus, and hearing loss.[1] Uncommon peripheral causes include cholesteatoma, otosclerosis, and a perilymphatic fistula. Cholesteatomas are cyst-like lesions filled with keratin debris that often involve the middle ear and mastoid air cells.[7] Otosclerosis is characterized by abnormal bone growth in the middle ear, resulting in conductive hearing loss and potentially affecting the cochlea, which can lead to tinnitus and vertigo.[8] A perilymphatic fistula is another uncommon cause of peripheral vertigo and often results from trauma.[1]

Central etiologies of vertigo should always be considered in the differential diagnosis, especially in older adults. Ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes, particularly involving the cerebellum or brainstem, are life-threatening and must be ruled out through history, physical examination, and other diagnostic tests if warranted.[1][9] Other significant central causes include tumors, especially those originating from the cerebellopontine angle. (see Image. Cerebellopontine Angle [CPA] Tumor, Magnetic Resonance Image [MRI]).[10]

Examples of such tumors include a brainstem glioma, medulloblastoma, and vestibular schwannoma, which can lead to sensorineural hearing loss as well as vertiginous symptoms.[1] Vestibular migraines are a common central cause of vertigo, characterized by unilateral headaches associated with nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia. Additionally, multiple sclerosis (MS) has been linked to both central and peripheral causes of vertigo; MS can cause vertigo by developing demyelinating plaques in the vestibular system pathways.[11] BPPV is a common peripheral cause of vertigo in patients with MS.[1] Among the different diseases previously discussed, other causes can lead to vertigo, such as medication-induced vertigo and psychological disorders, including mood, anxiety, and somatization. Medications associated with vertigo include anticonvulsants (eg, phenytoin) and salicylates.[1]

Epidemiology

Vertigo affects both men and women, but it is about 2 to 3 times more common in women than in men.[1] This condition has been associated with various comorbid conditions, including depression and cardiovascular disease. Prevalence increases with age and varies depending on the underlying diagnosis. Based on a general population survey, the 1-year prevalence of vertigo is approximately 5%, and the annual incidence is 1.4%. Dizziness, including vertigo, affects approximately 15% to over 20% of adults yearly.[12] Almost half of patients with migraine complain of vertigo, motion sickness, or mild hearing loss. [13]

For benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, the 1-year prevalence is about 1.6%, and is less than 1% for vestibular migraine. The impact of vertigo should not be underestimated, as nearly 80% of survey respondents reported an interruption in their daily activities, including employment, and required additional medical attention. The prevalence of Menière disease has recently been reported to be 0.51%, which is significantly higher than previous estimates.[12][14]

Pathophysiology

Most cases of vertigo are attributed to peripheral causes that typically present acutely. In contrast, central vertigo is, by definition, caused by pathology originating within the central nervous system. Nevertheless, the pathophysiology of the balance system demonstrates significant overlap. The peripheral labyrinths, brainstem, and cerebellum share the same blood supply, namely the vertebrobasilar arterial system.[15][16] Furthermore, disturbances may occur in the neuronal input processed by the central nervous system from cranial nerve VIII and in the integration of motor and sensory inputs related to vision and proprioception.[17][18]

Abnormalities in the peripheral vestibular system can cause symptoms of vertigo. These abnormalities may result from damage or dysfunction in parts like the vestibular labyrinth or the vestibular nerve, or occur alongside disturbances in the central vestibular system, specifically in the brainstem and cerebellum.[1] Although a lasting peripheral structural vestibular disturbance may persist, the symptom of vertigo is not permanent, as the central nervous system adapts over days to weeks due to neuroplasticity.[19][20][21]

Infections can cause vertigo through involvement of the peripheral or central vestibular system, with viral labyrinthitis being the most common example. Otomastoiditis is an infection of the tympanic and mastoid cavities, usually caused by bacterial agents, especially Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. Acute cerebellitis is a form of encephalitis limited to the cerebellum. This condition mainly affects children, with the Varicella-zoster virus identified as the primary causative agent. Finally, cholesteatoma can be acquired or congenital, occurring in the pars flaccida or pars tensa, and results from abnormal proliferation of keratinized stratified squamous epithelium.[22]

Central vertigo may arise from a variety of etiologies, including positional vertigo, cranial nerve impairments, transient ischemic attacks, acute cerebellar pathology, caudal cerebellar infarction, cerebrovascular disorders, cardiovascular risk factors such as atrial fibrillation, and neurological conditions. Tumors can induce vertigo by compressing structures within the central vestibular system. Schwannoma is the most common type of lesion in the cerebellopontine angle.[23] Meningioma is an extra-axial tumor in adults that can induce vertigo, ranking as the second most prevalent lesion in the cerebellopontine angle. Other neoplasms associated with vertigo include Glomus jugulare and glomus jugulotympanicum. These represent the primary tumors of the chemoreceptor system situated at the jugular foramen. Additionally, metastases should be considered in patients presenting with vertigo, including those with known primary neoplasms or multiple brain lesions.

History and Physical

The initial diagnosis aims to confirm whether the patient is experiencing vertigo since most patients report dizziness as their primary complaint. Vertigo is an abnormal sensation of movement or rotation experienced by the patient or their environment. To elicit actual vertigo symptoms, a clinician may ask, "Does it feel like the room is spinning around you?" or "Do you feel like you are the one spinning?"[1] Once vertigo has been identified, a comprehensive medical history helps the clinician distinguish between central and peripheral etiologies of vertigo. Eliciting a detailed timeline of symptom progression is among the most effective methodologies for determining the underlying cause. A clinician may classify symptoms as acute or chronic, recurrent or persistent, and progressive or nonprogressive. For example, chronic and recurrent vertigo lasting a few minutes or less is frequently associated with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. A solitary episode lasting from minutes to hours may be attributable to a vestibular migraine or potentially a more serious underlying condition, such as a transient ischemic attack. Conversely, episodes of longer duration, extending over days, can occur in both peripheral and central causes, such as vestibular neuritis or lesions at the cerebellopontine angle tumors.[1]

Once a timeline has been established, it is essential to assess for associated symptoms, as this can further assist in differentiating between central and peripheral etiologies. Nausea and vomiting are common during acute episodes of vertigo and are not indicative of any specific cause. Given the importance of ruling out central causes that may be progressive or life-threatening, such as vertebrobasilar stroke or multiple sclerosis, clinicians should inquire about any focal neurological symptoms, including diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, and numbness or weakness.[24] Additionally, other signs that clinicians should investigate include depressed consciousness, nystagmus, internuclear ophthalmoplegia, cranial nerve deficits, muscle weakness, hyperesthesia, ataxia, and cardiac signs such as murmurs, irregular heartbeats, tachycardia, or bradycardia.

An absence of focal neurologic symptoms does not entirely exclude the possibility of a serious central process; however, their presence serves as a red flag that necessitates further investigation. When considering the differential diagnosis of central causes of vertigo and related symptoms, clinicians should inquire about symptoms such as headache, photophobia, and visual auras, as these frequently accompany vestibular migraines. Additional symptoms associated with vertigo may originate from a peripheral lesion. For example, patients might experience deafness and tinnitus attributable to Ménière disease.[25] They may report a recent viral infection that can cause acute labyrinthitis and vestibular neuritis. Finally, it is essential to review a patient's medication list and social history for any substance or alcohol use. Medications that can impact vestibular function include anticonvulsants, salicylates, and antibiotics.[26]

When combined with a comprehensive history, a focused physical examination can help further differentiate between a peripheral and a central cause of vertigo. Assessing for nystagmus is a key portion of the physical examination when a patient presents with vertiginous symptoms.[1] A functional vestibular system allows one to maintain gaze during rotation through vestibulo-ocular reflexes. With unilateral dysfunction in the vestibular system, the eyes drift slowly away from a target and then correct rapidly in the opposite direction, resulting in a “beat” in the direction of the fast phase. In a peripheral vestibular lesion, the rapid phase is away from the affected side, and the frequency and amplitude of nystagmus increase with a gaze toward the side of the fast phase. For instance, a rightward gaze increases right-beating nystagmus. In peripheral lesions, the predominant direction of nystagmus remains the same regardless of the direction of gaze, while central lesions may present with nystagmus that reverses direction.[27]

Central lesions can present with nystagmus in any direction, while peripheral lesions often present with horizontal nystagmus with a torsional component. Noting that nystagmus resulting from a peripheral lesion is never purely torsional or vertical is essential. The head impulse or thrust technique is a physical examination technique to further determine the etiology. In this exam, patients are asked to fix their gaze on a distant target, using prescription eyeglasses if necessary. The head is turned quickly to the right or left by about 15 degrees. A typical response occurs when the eyes remain on the target. An abnormal response is when the eyes are dragged off the target in the direction of head turning, followed by a corrective saccade back to the target. This response implies a peripheral lesion resulting in a deficient vestibulo-ocular reflex on the side of the head turn.

Finally, a clinician may test for skew, which involves the examiner covering one eye and observing for a vertical or horizontal shift in the uncovered eye. Central lesions sometimes produce a slight skew deviation. When the head impulse test is combined with an examination of nystagmus and a test for skew, this is referred to as the Head Impulse-Nystagmus-Test for Skew (HINTS) test.[28] A standard head impulse test on both sides with direction-changing nystagmus and/or skew deviation is concerning for a central lesion. An abnormal head impulse test with unidirectional nystagmus and absent skew deviation strongly suggests a peripheral lesion. The HINTS test may be more sensitive for diagnosing acute stroke than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) within the first 48 hours following symptom onset.[29]

Other physical examination techniques may be used to diagnose and treat vertigo, including the Dix-Hallpike maneuver.[30] This is the diagnostic test of choice when BPPV involving the posterior semicircular canals is suspected. Dix-Hallpike consists of 2 maneuvers. A patient sits on an exam table facing forward with eyes open, and the clinician turns the patient's head 45 degrees to the right. The clinician supports the patient's head while the patient quickly lies back to a supine position, with the head hanging about 20 degrees off the end of the table. The patient remains in this position for 30 seconds before returning to the upright position, where they are observed for another 30 seconds. This maneuver is repeated with the head turned to the left. The test is positive if, at any point, the maneuvers produce vertigo with or without nystagmus.[1]

Another helpful diagnostic maneuver for peripheral vertigo is the Unterberger test, which consists of 2 maneuvers. A patient stands in an upright position with their eyes closed. The clinician then instructs the patient to walk in place for 60 seconds. The test is positive if the body is rotated to one side while walking in place.[31] Furthermore, gait and balance testing can also help localize the issue. Patients with unilateral peripheral disorders often lean or fall toward the side of the lesion. In contrast, patients with cerebellar lesions frequently cannot walk without assistance, and the direction of falling during Romberg testing is variable. Many primary care and specialist clinicians overlook the fundamentals of history and physical examination, resulting in unnecessary imaging and medication.[32]

A thorough head, neck, and neurologic examination is essential. The otoscopic exam should rule out obvious infections, such as acute otitis media, and bedside hearing tests can help distinguish other causes of vertigo. Weber and Rinne tests are often done at the bedside to screen for conductive and sensorineural hearing loss.[33] However, audiometry and tympanometry are more sensitive than bedside testing in detecting hearing loss and middle ear fluid.

A unilateral hearing loss points strongly to a peripheral etiology, but further diagnostic imaging with MRI, usually with gadolinium, is warranted if a cause can not be identified. Another practical test that can be performed is the auditory brain response, also known as brainstem auditory evoked potentials, which are objective measurements of the auditory pathway function from the auditory nerve to the mesencephalon. There is insufficient high-quality evidence to support the diagnostic value of the absence of hearing loss, as assessed by pure tone audiometry, in predicting BPPV in patients with vertigo.[34]

Evaluation

The acronym STANDING describes a 4-step algorithm based on nystagmus observation and well-known diagnostic maneuvers; it includes the discrimination between SponTAneous and positional or gaze-evoked nystagmus, evaluation of the Nystagmus Direction (whether it is unidirectional or direction-changing), the head Impulse test, and the assessment of equilibrium (staNdinG).[35] Laboratory testing often fails to identify the cause of vertigo. Diagnostic brain imaging is recommended if a central lesion is suspected. Clinicians may find it difficult to distinguish between a central lesion, such as an infarction, and a peripheral lesion, like vestibular neuritis, where vertigo symptoms can last for days.

In such cases, neuroimaging is advised for patients with stroke risk factors, focal neurologic deficits, a new headache, or when the physical exam does not fully match a peripheral lesion. The preferred methods are brain MRI and magnetic resonance (MR) angiography, as computed tomography (CT) scans are less sensitive than MRI for detecting and evaluating central lesions due to their limited resolution of posterior fossa structures. However, if a brain MRI is unavailable or contraindicated, a CT scan with thin cuts may be used, primarily through the brainstem and cerebellum.[22]

Treatment / Management

Managing vertigo depends on its etiology, and addressing the underlying cause often alleviates the symptoms. Pharmacological interventions may help suppress vestibular symptoms during acute episodes, which can persist for several hours to days. The most frequently employed for symptomatic relief include antihistamines, calcium channel blockers, benzodiazepines, and antiemetics. Among antihistamines, meclizine and betahistine are used.[36] Calcium channel blockers, such as cinnarizine, are included in this category. Due to their sedative effects, caution is recommended when prescribing antihistamines, benzodiazepines, and antiemetics to older adults. Steroids can be beneficial in some instances. Healthcare professionals should be aware that vestibular suppressants should be used for a limited duration, as excessive use may unnecessarily hinder the brain and central nervous system's natural compensatory mechanisms for peripheral vertigo. (A1)

Additional nonpharmacologic treatments for patients with permanent unilateral or bilateral vestibular dysfunction include physical therapy with vestibular rehabilitation.[37] Vestibular rehabilitation exercises train the brain to maintain balance using alternative visual and proprioceptive cues. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the benefits of vestibular rehabilitation, including a reduction in vertiginous symptoms, a decrease in position- and movement-provoked dizziness, and an improvement in activities of daily living.[38][39][40] In some patients, particularly those diagnosed with vestibular neuritis, a combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapy is recommended.(A1)

Corticosteroids are recommended in the acute setting, in addition to vestibular rehabilitation, for vestibular neuritis. In patients with Ménière disease, lifestyle adjustments, medication, and vestibular rehabilitation may be effective.[41] Patients with Ménière disease may be sensitive to a high-salt diet, caffeine, and alcohol. Avoiding known triggers can help alleviate symptoms. Diuretics may also be prescribed when diet modification alone is not sufficient in controlling symptoms. Acute episodes can be symptomatically treated with vestibular suppressants like meclizine.

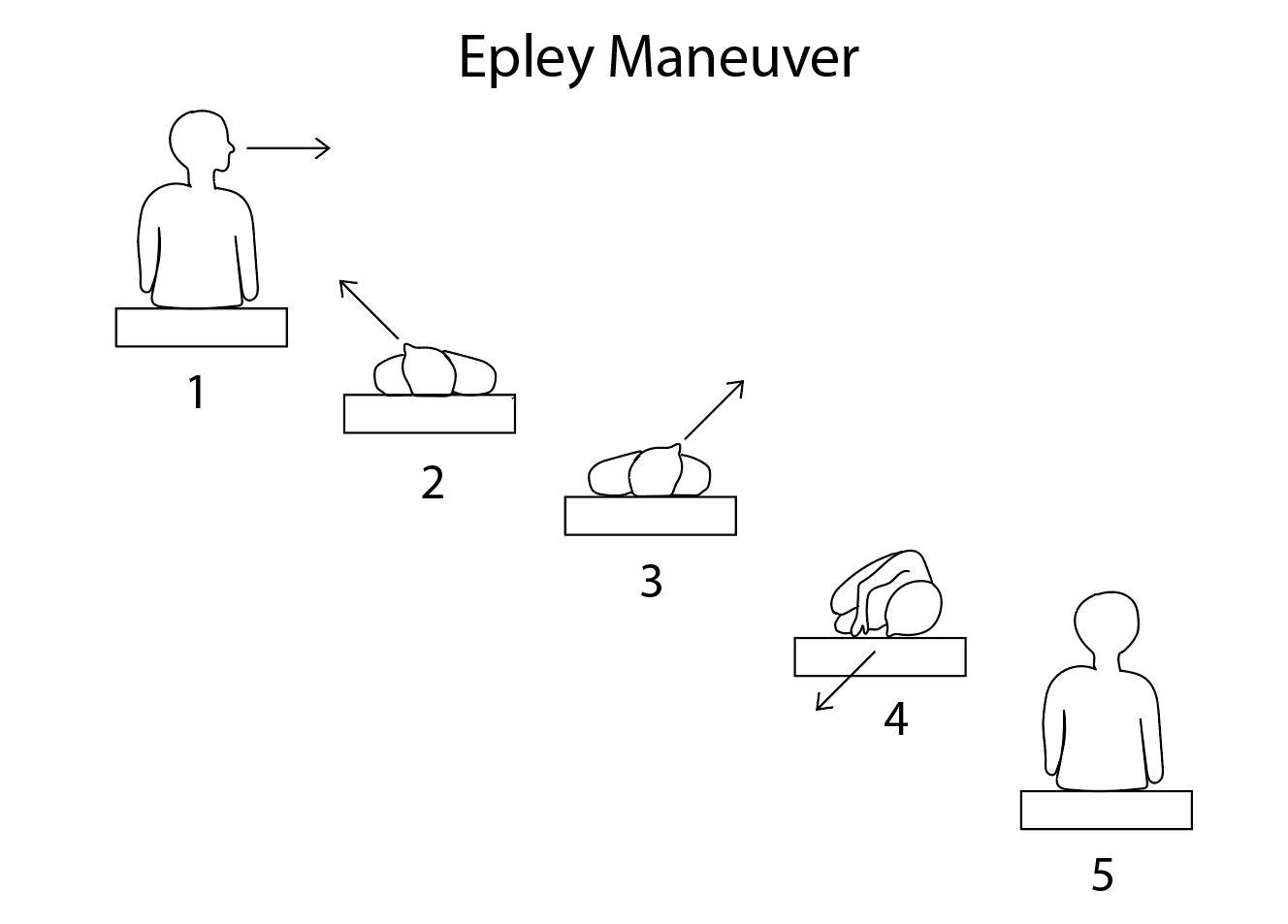

Patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo benefit from nonpharmacologic agents. The primary treatment for BPPV focuses on head rotation maneuvers that dislodge calcium deposits back to the vestibule through canalith repositioning, also known as the Epley maneuver.[42] The benefit of the Epley maneuver is that it can be performed at home by the patient. To perform a modified Epley maneuver (as shown in the image), instruct the patient to position themselves upright on a bed with their head turned 45 degrees to the left and a pillow behind them. The pillow should be placed directly under the shoulders when lying on one's back. Once the patient is in position, they should quickly lie back onto the pillow so that their head is reclined on the bed. They should hold this position for 30 seconds. Without raising their head, they should turn their head 90 degrees to the opposite side (right) and hold this position for another 30 seconds.(A1)

After 30 seconds, they should turn their body and head another 90 degrees to the right and wait for 30 seconds. Finally, they should sit up on the right side of the bed. This maneuver can be repeated, starting on the opposite side, and should be performed at least 3 times a day until the patient has no further episodes of positional vertigo for 24 hours. The Epley maneuver is effective in 50% to 90% of patients.[43] Unfortunately, BPPV is intractable in a select number of patients, and surgical treatment can be an option, particularly if symptoms are disabling. Surgical options include occlusion of the posterior canal with bony plugs or transection of the posterior ampullary nerve—either surgical procedure risks hearing loss (see Image. Epley Maneuver).

Management of central vertigo should focus on identifying and addressing the underlying cause. Migraine and related vertigo are not entirely understood, but they should be considered. [44] Transient ischemic attacks can cause vertigo and focal neurological symptoms. Stroke and stroke prevention should be considered in the differential diagnosis, along with heart disease. Some patients will present with orthostatic hypotension, and it is essential to determine the etiology instead of using vestibular suppressants.[45] Additionally, neurological causes, especially multiple sclerosis, tumors, and malformations of the posterior fossa, need to be evaluated.[46](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of vertigo is broad because it can result from a central or peripheral lesion in the vestibular system. Therefore, it is important to distinguish vertigo from symptoms of disequilibrium, presyncope, and lightheadedness (see Table. Disease Category and Disease Entities in Vertigo). A lengthy list of vascular, infectious, traumatic, inflammatory, demyelinating, metabolic, iatrogenic, and neoplastic causes can lead to these symptoms.[47]

Table. Disease Category and Disease Entities in Vertigo

| Disease Category | Disease Entities |

| Vascular | Cerebrovascular disease, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, vestibular migraine |

| Infectious |

Meningitis, herpes simplex encephalitis, brainstem encephalitis (rhombencephalitis), otomastoiditis |

| Traumatic | Traumatic brain injury (postconcussion syndrome) |

| Inflammatory | Vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis |

| Demyelinating | Multiple sclerosis, Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-associated disease |

| Metabolic | Anemia (acute and chronic), alcoholic cerebellar degeneration, Wernicke encephalopathy (thiamine deficiency) |

| Iatrogenic | Medication-induced |

| Neoplastic | Cerebellopontine angle tumors, metastasis, paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration |

| Idiopathic | Ménière disease, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo |

Prognosis

The prognosis is contingent upon the etiology of vertigo; typically, peripheral causes are associated with a more favorable outlook, whereas central causes tend to have a less favorable prognosis. The recurrence rate of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is approximately 50% over 5 years. Furthermore, dizziness attributable to anxiety persists in nearly one-third of patients one year following vestibular treatment for neuritis.[14] According to Perrez-Garrigues et al, the number of episodes of vertigo is higher in the first years of the disease and decreases in later years, regardless of whether patients receive treatment; most patients reach a "steady-state phase free of vertigo."[48]

As with vertigo, hearing loss is most pronounced in the early years of the disease and tends to stabilize in later years. Usually, there is little to no recovery from hearing loss.[49] The acute vertigo associated with labyrinthitis typically resolves within a few days; milder symptoms may persist for several weeks. The prognosis is usually good if the patient has no serious neurological sequelae. However, patients with neurological complications from central causes may require further interventions.[50]

Complications

The key to arriving at a diagnosis is to differentiate vertigo from other causes of dizziness or imbalance and distinguish between central and peripheral causes of vertigo. An accurate diagnosis is essential and critical in cases of life-threatening conditions. Peripheral causes of vertigo are usually associated with little to no complications. Complications arising from the central causes of vertigo are variable, depending on whether the etiology is accurately identified and properly diagnosed and managed.[51]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education depends on the underlying cause of vertigo. Prevention can be challenging since patients may exhibit a wide range of symptoms. For example, labyrinthitis often results from another infection, such as otitis media or meningitis. Therefore, early diagnosis and proper management are crucial for preventing labyrinthitis and reducing the risk of long-term complications. Populations should keep their immunizations up to date to reduce the risk of contracting measles, mumps, or rubella. Patients experiencing vertigo should be encouraged to start mobilizing as soon as possible, as this is believed to aid in the prognosis of vestibular compensation.[2] Patients who receive a prolonged course of benzodiazepines and/or antihistamines to treat their vertigo appear to have delayed vestibular recovery.

Another example is Ménière disease, which is suspected when a patient presents with unilateral hearing loss, episodes of vertigo lasting from several minutes to several hours, and tinnitus. Such patients should consult their primary care physician or visit the emergency department for further evaluation. In the case of BPPV, it is advisable to clarify that this condition is non-life-threatening. Communicating a favorable prognosis can reassure patients that their condition is not severe. Additionally, patients should be informed that recurrences are common even after successful treatment with repositioning maneuvers; further interventions may be required.

Pearls and Other Issues

Recent consensus guidelines recommend against routine, unnecessary radiographic imaging for patients who meet the diagnostic criteria for BPPV, unless additional signs or symptoms suggest otherwise. No additional vestibular testing is required for patients diagnosed with BPPV who do not exhibit other vestibular signs or symptoms. Routine, prolonged use of vestibular suppressants, such as antihistamines or benzodiazepines, should be avoided. If red flag signs indicating a central cause of vertigo are present, further evaluation with a brain MRI or thin-slice brain CT scan is advised. Despite increased access to diagnostic and imaging tools, a detailed history and focused physical examination remain essential for accurate diagnosis and management.[52]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Vertigo is a common condition that is best managed by an interprofessional team, including primary care clinicians, otolaryngologists, neurologists, specialized nurses, physical therapists, and pharmacists. Early detection and treatment are crucial to reducing morbidity and mortality. Clinicians should address the immediate symptoms while remaining alert to various potential causes. Patient care requires collaboration among healthcare professionals to ensure patient-centered outcomes. Professionals require core clinical skills to accurately diagnose and treat vertigo, as well as to understand the diverse presentations and overlapping causes. An evidence-based, strategic approach helps optimize treatments and lessen side effects.

Ethical principles must guide decisions, ensuring informed consent and respecting patient autonomy. Each team member should understand their role and contribute their expertise to foster a multidisciplinary approach. Clear communication among team members is essential for seamless information sharing and joint decision-making. Effective care coordination ensures a smooth progression from diagnosis through treatment and follow-up, reducing errors and enhancing patient safety. By applying skills, strategies, ethics, and responsibilities, as well as effective communication and coordination, healthcare providers can deliver comprehensive, patient-focused care, leading to better outcomes and improved team effectiveness in vertigo management.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Labuguen RH. Initial evaluation of vertigo. American family physician. 2006 Jan 15:73(2):244-51 [PubMed PMID: 16445269]

Bouccara D, Rubin F, Bonfils P, Lisan Q. [Management of vertigo and dizziness]. La Revue de medecine interne. 2018 Nov:39(11):869-874. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2018.02.004. Epub 2018 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 29496272]

Post RE, Dickerson LM. Dizziness: a diagnostic approach. American family physician. 2010 Aug 15:82(4):361-8, 369 [PubMed PMID: 20704166]

Paparella MM, Djalilian HR. Etiology, pathophysiology of symptoms, and pathogenesis of Meniere's disease. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2002 Jun:35(3):529-45, vi [PubMed PMID: 12486838]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLorente-Piera J, Suárez-Vega V, Blanco-Pareja M, Liaño G, Garaycochea O, Dominguez P, Manrique-Huarte R, Pérez-Fernández N. Early and certain Ménière's disease characterization of predictors of endolymphatic hydrops. Frontiers in neurology. 2025:16():1566438. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1566438. Epub 2025 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 40356628]

Yokose M, Shimizu T. A Case of Ramsay Hunt Syndrome That Began with Vestibular Symptoms: A Great Mimicker. The American journal of medicine. 2021 Apr:134(4):e271-e272. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.09.049. Epub 2020 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 33144130]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSemaan MT, Megerian CA. The pathophysiology of cholesteatoma. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2006 Dec:39(6):1143-59 [PubMed PMID: 17097438]

Stankovic KM, McKenna MJ. Current research in otosclerosis. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2006 Oct:14(5):347-51 [PubMed PMID: 16974150]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchneider JI, Olshaker JS. Vertigo, vertebrobasilar disease, and posterior circulation ischemic stroke. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2012 Aug:30(3):681-93. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2012.06.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22974644]

Mukherjee A, Chatterjee SK, Chakravarty A. Vertigo and dizziness--a clinical approach. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 2003 Nov:51():1095-101 [PubMed PMID: 15260396]

Pula JH, Newman-Toker DE, Kattah JC. Multiple sclerosis as a cause of the acute vestibular syndrome. Journal of neurology. 2013 Jun:260(6):1649-54. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6850-1. Epub 2013 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 23392781]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNeuhauser HK. The epidemiology of dizziness and vertigo. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2016:137():67-82. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63437-5.00005-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27638063]

Cha YH, Baloh RW. Migraine associated vertigo. Journal of clinical neurology (Seoul, Korea). 2007 Sep:3(3):121-6. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2007.3.3.121. Epub 2007 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 19513278]

Neuhauser HK. Epidemiology of vertigo. Current opinion in neurology. 2007 Feb:20(1):40-6 [PubMed PMID: 17215687]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZibis A, Mitrousias V, Galanakis N, Chalampalaki N, Arvanitis D, Karantanas A. Variations of transverse foramina in cervical vertebrae: what happens to the vertebral artery? European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2018 Jun:27(6):1278-1285. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5523-2. Epub 2018 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 29455293]

Yuan SM. Aberrant Origin of Vertebral Artery and its Clinical Implications. Brazilian journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2016 Feb:31(1):52-9. doi: 10.5935/1678-9741.20150071. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27074275]

Rivera M, Porras-Segovia A, Rovira P, Molina E, Gutiérrez B, Cervilla J. Associations of major depressive disorder with chronic physical conditions, obesity and medication use: Results from the PISMA-ep study. European psychiatry : the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists. 2019 Aug:60():20-27. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.04.008. Epub 2019 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 31100609]

Mathkour M, Helbig B, McCormack E, Amenta PS. Acute Presentation of Vestibular Schwannoma Secondary to Intratumoral Hemorrhage: A Case Report and Literature Review. World neurosurgery. 2019 Sep:129():157-163. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.05.075. Epub 2019 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 31103763]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohkura K. [Vertigo and dizziness]. Rinsho shinkeigaku = Clinical neurology. 2021 May 19:61(5):279-287. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.cn-001570. Epub 2021 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 33867417]

Mateos-Aparicio P, Rodríguez-Moreno A. The Impact of Studying Brain Plasticity. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience. 2019:13():66. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00066. Epub 2019 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 30873009]

Laskowitz D, Grant G, Sophie Su Y, Veeravagu A, Grant G. Neuroplasticity after Traumatic Brain Injury. Translational Research in Traumatic Brain Injury. 2016:(): [PubMed PMID: 26583189]

Ribeiro BNF, Correia RS, Antunes LO, Salata TM, Rosas HB, Marchiori E. The diagnostic challenge of dizziness: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Radiologia brasileira. 2017 Sep-Oct:50(5):328-334. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2016.0054. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29085167]

Taylor RL, Chen L, Lechner C, Aw ST, Welgampola MS. Vestibular schwannoma mimicking horizontal cupulolithiasis. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2013 Aug:20(8):1170-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.08.013. Epub 2013 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 23665081]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEggers SDZ, Kattah JC. Approaching Acute Vertigo With Diplopia: A Rare Skew Deviation in Vestibular Neuritis. Mayo Clinic proceedings. Innovations, quality & outcomes. 2020 Apr:4(2):216-222. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.12.003. Epub 2020 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 32280933]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHavia M, Kentala E, Pyykkö I. Hearing loss and tinnitus in Meniere's disease. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2002 Apr:29(2):115-9 [PubMed PMID: 11893444]

MYERS EN, BERNSTEIN JM, FOSTIROPOLOUS G. SALICYLATE OTOTOXICITY: A CLINICAL STUDY. The New England journal of medicine. 1965 Sep 9:273():587-90 [PubMed PMID: 14329630]

Büttner U, Helmchen C, Brandt T. Diagnostic criteria for central versus peripheral positioning nystagmus and vertigo: a review. Acta oto-laryngologica. 1999 Jan:119(1):1-5 [PubMed PMID: 10219377]

Kattah JC. Use of HINTS in the acute vestibular syndrome. An Overview. Stroke and vascular neurology. 2018 Dec:3(4):190-196. doi: 10.1136/svn-2018-000160. Epub 2018 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 30637123]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009 Nov:40(11):3504-10. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.551234. Epub 2009 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 19762709]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHalker RB, Barrs DM, Wellik KE, Wingerchuk DM, Demaerschalk BM. Establishing a diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo through the dix-hallpike and side-lying maneuvers: a critically appraised topic. The neurologist. 2008 May:14(3):201-4. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31816f2820. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18469678]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSun T, Lin Y, Huang Y, Pan Y. A preliminary clinical study related to vestibular migraine and cognitive dysfunction. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2024:18():1512291. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2024.1512291. Epub 2024 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 39764359]

Ulytė A, Valančius D, Masiliūnas R, Paškonienė A, Lesinskas E, Kaski D, Jatužis D, Ryliškienė K. Diagnosis and treatment choices of suspected benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: current approach of general practitioners, neurologists, and ENT physicians. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2019 Apr:276(4):985-991. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05313-y. Epub 2019 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 30694376]

Bagai A, Thavendiranathan P, Detsky AS. Does this patient have hearing impairment? JAMA. 2006 Jan 25:295(4):416-28 [PubMed PMID: 16434632]

Dorresteijn PM, Ipenburg NA, Murphy KJ, Smit M, van Vulpen JK, Wegner I, Stegeman I, Grolman W. Rapid Systematic Review of Normal Audiometry Results as a Predictor for Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2014 Jun:150(6):919-24. doi: 10.1177/0194599814527233. Epub 2014 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 24642523]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVanni S, Pecci R, Edlow JA, Nazerian P, Santimone R, Pepe G, Moretti M, Pavellini A, Caviglioli C, Casula C, Bigiarini S, Vannucchi P, Grifoni S. Differential Diagnosis of Vertigo in the Emergency Department: A Prospective Validation Study of the STANDING Algorithm. Frontiers in neurology. 2017:8():590. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00590. Epub 2017 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 29163350]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShih RD, Walsh B, Eskin B, Allegra J, Fiesseler FW, Salo D, Silverman M. Diazepam and Meclizine Are Equally Effective in the Treatment of Vertigo: An Emergency Department Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Jan:52(1):23-27. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.09.016. Epub 2016 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 27789115]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVenosa AR, Bittar RS. Vestibular rehabilitation exercises in acute vertigo. The Laryngoscope. 2007 Aug:117(8):1482-7 [PubMed PMID: 17592393]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCohen HS, Kimball KT. Increased independence and decreased vertigo after vestibular rehabilitation. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2003 Jan:128(1):60-70 [PubMed PMID: 12574761]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBittar RS, Pedalini ME, Lorenzi MC, Formigoni LG. Treating vertigo with vestibular rehabilitation: results in 155 patients. Revue de laryngologie - otologie - rhinologie. 2002:123(1):61-5 [PubMed PMID: 12201005]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTsukamoto HF, Costa Vde S, Silva RA Junior, Pelosi GG, Marchiori LL, Vaz CR, Fernandes KB. Effectiveness of a Vestibular Rehabilitation Protocol to Improve the Health-Related Quality of Life and Postural Balance in Patients with Vertigo. International archives of otorhinolaryngology. 2015 Jul:19(3):238-47. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1547523. Epub 2015 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 26157499]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGottshall KR, Topp SG, Hoffer ME. Early vestibular physical therapy rehabilitation for Meniere's disease. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2010 Oct:43(5):1113-9. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.05.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20713248]

Cetin YS, Ozmen OA, Demir UL, Kasapoglu F, Basut O, Coskun H. Comparison of the effectiveness of Brandt-Daroff Vestibular training and Epley Canalith repositioning maneuver in benign Paroxysmal positional vertigo long term result: A randomized prospective clinical trial. Pakistan journal of medical sciences. 2018 May-Jun:34(3):558-563. doi: 10.12669/pjms.343.14786. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30034415]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBerisavac II, Pavlović AM, Trajković JJ, Šternić NM, Bumbaširević LG. Drug treatment of vertigo in neurological disorders. Neurology India. 2015 Nov-Dec:63(6):933-9 [PubMed PMID: 26588629]

Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J, Waterston J, Seemungal B, Carey J, Bisdorff A, Versino M, Evers S, Newman-Toker D. Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria. Journal of vestibular research : equilibrium & orientation. 2012:22(4):167-72. doi: 10.3233/VES-2012-0453. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23142830]

Kim HA, Bisdorff A, Bronstein AM, Lempert T, Rossi-Izquierdo M, Staab JP, Strupp M, Kim JS. Hemodynamic orthostatic dizziness/vertigo: Diagnostic criteria. Journal of vestibular research : equilibrium & orientation. 2019:29(2-3):45-56. doi: 10.3233/VES-190655. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30883381]

Carlson ML, Tveiten ØV, Driscoll CL, Neff BA, Shepard NT, Eggers SD, Staab JP, Tombers NM, Goplen FK, Lund-Johansen M, Link MJ. Long-term dizziness handicap in patients with vestibular schwannoma: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2014 Dec:151(6):1028-37. doi: 10.1177/0194599814551132. Epub 2014 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 25273693]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZwergal A, Dieterich M. [Update on diagnosis and therapy in frequent vestibular and balance disorders]. Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie. 2021 May:89(5):211-220. doi: 10.1055/a-1432-1849. Epub 2021 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 33873210]

Perez-Garrigues H, Lopez-Escamez JA, Perez P, Sanz R, Orts M, Marco J, Barona R, Tapia MC, Aran I, Cenjor C, Perez N, Morera C, Ramirez R. Time course of episodes of definitive vertigo in Meniere's disease. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2008 Nov:134(11):1149-54. doi: 10.1001/archotol.134.11.1149. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19015442]

Stahle J. Advanced Meniere's disease. A study of 356 severely disabled patients. Acta oto-laryngologica. 1976 Jan-Feb:81(1-2):113-9 [PubMed PMID: 1251702]

Rizvi I, Garg RK, Malhotra HS, Kumar N, Sharma E, Srivastava C, Uniyal R. Ventriculo-peritoneal shunt surgery for tuberculous meningitis: A systematic review. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2017 Apr 15:375():255-263. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.02.008. Epub 2017 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 28320142]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLee AT. Diagnosing the cause of vertigo: a practical approach. Hong Kong medical journal = Xianggang yi xue za zhi. 2012 Aug:18(4):327-32 [PubMed PMID: 22865178]

Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, Edlow JA, El-Kashlan H, Fife T, Holmberg JM, Mahoney K, Hollingsworth DB, Roberts R, Seidman MD, Steiner RW, Do BT, Voelker CC, Waguespack RW, Corrigan MD. Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update). Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2017 Mar:156(3_suppl):S1-S47. doi: 10.1177/0194599816689667. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28248609]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence