Introduction

Tonsils are lymphoid tissue aggregates positioned near the entrance of the digestive and respiratory tracts, where they contribute significantly to immune defense. These structures initiate the first immunological response to inhaled or ingested pathogens.[1] The lymphatic tissues of the oropharynx form a circumferential arrangement known as the Waldeyer ring, which includes the palatine tonsils, commonly referred to as “the tonsils,” as well as the adenoid, lingual, and tubal tonsils.[2]

Tonsils serve as key immunological sentinels, particularly during early life, and are frequently involved in infectious and inflammatory conditions such as tonsillitis and peritonsillar abscess. The tonsils are among the most commonly excised lymphoid organs in otolaryngologic surgery because of their propensity for recurrent infection and hypertrophy. A thorough understanding of tonsillar anatomy and function enables clinicians to diagnose head and neck infections more accurately and determine appropriate indications for surgical intervention.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Like other lymphoid tissues, the tonsils contribute to immune defense by responding to infections and foreign antigens. The tonsils are strategically located at the junction of the respiratory and digestive tracts, where they initiate lymphokine and immunoglobulin production in response to inhaled or ingested pathogens.

Composed primarily of B-cell lymphoid tissue, the tonsils support mucosal secretory immunity. Specialized antigen-capturing cells, known as M cells, are present on the tonsillar surface and facilitate the uptake of microbial antigens. After antigen recognition, M cells stimulate resident T and B lymphocytes, initiating a localized immune response.[3] Activated B cells proliferate within the germinal centers of the tonsils, where memory B cells mature and are retained for future antigen exposure.[4] These B cells also produce immunoglobulin A, a key antibody in mucosal immunity. The cellular architecture of the tonsils closely resembles that of the Peyer patches in the gastrointestinal tract, which monitor and regulate intestinal bacterial populations.

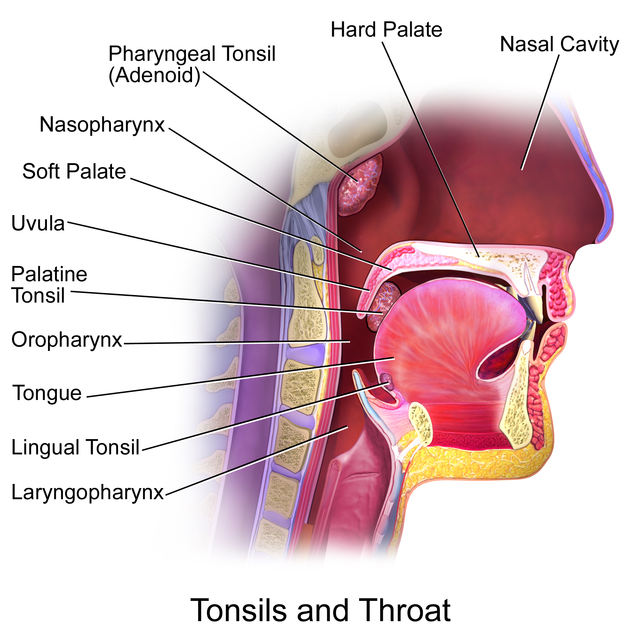

The lymphoid tissue of the upper aerodigestive tract forms the Waldeyer ring, named for its noncontinuous, circumferential configuration in the oropharynx. This ring comprises the palatine, tubal, pharyngeal, and lingual tonsils (see Image. Tonsils and Throat).

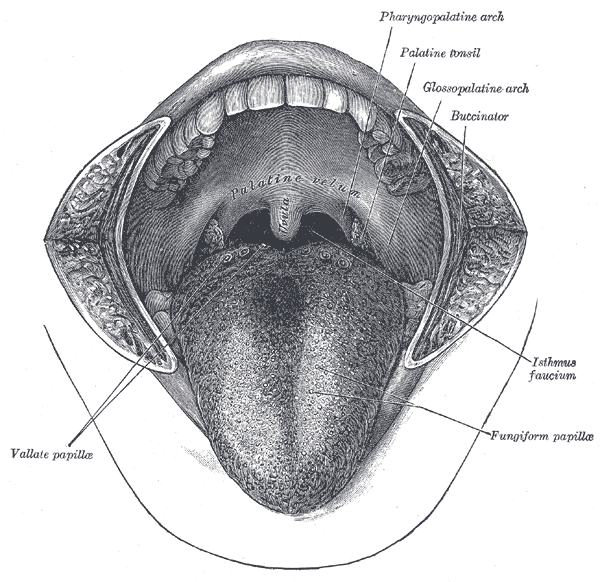

The palatine tonsils are located in the posterior oral cavity, positioned bilaterally between the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches within the tonsillar fossae (see Image. Oral Cavity and Palatine Tonsils). The free medial surfaces of these structures project into the oropharynx and are readily visible on clinical examination, while the lateral surfaces are covered by a fibrous hemicapsule. This capsule, along with intervening loose areolar tissue, separates the tonsils from the underlying superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle.

The lingual tonsil lies in the submucosa of the posterior 3rd of the tongue and consists of nodular lymphoid tissue forming the midline component of the Waldeyer ring at the oropharyngeal level. The pharyngeal tonsil is situated in the roof of the nasopharynx and consists of submucosal lymphoid tissue collections. The tubal tonsils, positioned laterally, surround the pharyngeal openings of the eustachian tubes and complete the ring.

Embryology

Tonsils are derivatives of the 2nd pharyngeal pouch.[5] These structures typically appear around the 4th or 5th month of gestation and continue to develop after birth, reaching full size at puberty. Tonsillar and adenoidal tissues exhibit peak immunologic activity between 4 and 12 years of age, followed by progressive atrophy beginning after puberty.[6][7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The palatine tonsils lie along the lateral wall of the oropharynx, situated in a fossa between the anterior and posterior pillars. Five arteries contribute to the vascular supply of these structures. The primary source is the tonsillar branch of the facial artery, which enters at the lower pole. Additional arterial input arises from the ascending palatine, dorsal lingual, ascending pharyngeal, and lesser palatine arteries.[8] Venous drainage occurs mainly via the peritonsillar venous plexus, which empties into the pharyngeal and lingual veins before reaching the internal jugular vein.

Although the internal carotid artery does not directly supply the tonsils, it lies approximately 2.5 cm posterolateral to their position. Surgical manipulation in this region requires caution to prevent vascular injury.[9]

Nerves

The tonsils receive afferent innervation from the tonsillar plexus, which includes contributions from the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) via the lesser palatine nerves, and the glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX). The glossopharyngeal nerve extends beyond the tonsillar region to provide general sensory and taste innervation to the posterior 3rd of the tongue. Among the nerves in this region, the glossopharyngeal nerve is the most vulnerable to injury during tonsillectomy.

Surgical Considerations

Tonsillectomy

Surgical removal of the tonsils is referred to as a "tonsillectomy." Hemorrhagic tonsillitis constitutes an absolute indication for the procedure.[10] Relative indications include recurrent or chronic pharyngotonsillitis, peritonsillar abscess, and streptococcal pharyngitis.

Tonsillectomy involves dissection between the tonsillar capsule and the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle, using either a “hot” or “cold” technique. The hot technique employs electrocautery for simultaneous dissection and hemostasis. In the cold technique, a superior incision is made through the mucosa, followed by blunt dissection to separate the tonsil from its bed. Final separation along the inferior pole is achieved using a snare. Cold dissection has demonstrated superior postoperative pain outcomes, while electrocautery is associated with reduced intraoperative blood loss. Newer modalities, such as carbon dioxide laser, ultrasound, and radiofrequency ablation, have been introduced to reduce postoperative morbidity, though further evidence is needed to support widespread adoption of these approaches.

Tonsillectomy complications are classified as acute, subacute, or delayed. Acute complications include airway obstruction due to edema, bleeding, and postobstructive pulmonary edema. Subacute complications include secondary hemorrhage, dehydration, and weight loss. Delayed or chronic complications include velopharyngeal insufficiency and nasopharyngeal stenosis.[11]

Adenotonsillectomy

Surgical removal of both the tonsils and adenoids is indicated in selected cases. This combined procedure is referred to as an "adenotonsillectomy." Absolute indications include adenotonsillar hypertrophy with obstructive sleep apnea, abnormal dentofacial development, and suspected or confirmed malignancy. Relative indications include dysphagia, speech disturbance, and chronic halitosis. Adenotonsillectomy does not result in any clinically significant immunologic deficiency. Contraindications include acute infection, anemia, coagulopathy (whether inherited or acquired), and elevated anesthetic risk.[12]

Clinical Significance

Tonsilloliths

Tonsilloliths, or tonsil stones, are whitish, malodorous concretions that form within the tonsillar crypts due to bacterial colonization and retained cellular debris. Most are asymptomatic but may cause halitosis, otalgia, or a foreign body sensation. Management is typically conservative, with patients advised to dislodge stones manually using cotton swabs. Surgical extraction may be necessary for large or symptomatic lesions. Mouth rinses and gargling can provide symptomatic relief, particularly in cases of halitosis.[13]

Bacterial Tonsillitis

Acute bacterial tonsillitis presents with an abrupt-onset sore throat, enlarged erythematous or exudative tonsils, halitosis, and tender cervical lymphadenopathy (see Image. Tonsillitis). Distinguishing bacterial from viral tonsillitis can be clinically challenging. Viral infections are managed supportively, while bacterial tonsillitis is treated with analgesics and antibiotics, typically amoxicillin or macrolides. Recurrent tonsillitis may warrant surgical intervention. The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery recommends tonsillectomy in patients with 7 documented infections in a year, 5 per year for 2 consecutive years, or 3 per year for 3 consecutive years.[14]

Adenotonsillar Disease

Adenotonsillar disease encompasses recurrent infections of the tonsils and adenoids. Patients may present with either acute or chronic adenoiditis. Clinical distinction is often difficult because symptoms frequently overlap with those of viral or bacterial upper respiratory tract infections. Adenoiditis typically presents with fever, purulent nasal discharge, and nasal obstruction and is frequently accompanied by otalgia. Group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes) is a common bacterial cause of acute tonsillitis. Chronic inflammation may lead to hypertrophy of both the tonsils and adenoids. In particular, adenoid hypertrophy can contribute to upper airway obstruction and is implicated in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea.

Peritonsillar Abscess

Peritonsillar abscess, also known as quinsy, refers to a localized collection of purulent material between the tonsillar capsule and the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle. This complication arises when infection extends beyond the tonsillar capsule into the peritonsillar space. Clinical features include dysphagia, odynophagia, trismus, and a characteristic muffled or “hot potato” voice.[15] Examination may reveal enlarged, inflamed tonsils, bulging of the soft palate, and uvular deviation toward the contralateral side. Management options include needle aspiration, which is effective in up to 90% of cases. Antibiotic therapy should follow aspiration, with agents such as clindamycin that provide robust gram-positive coverage. Tonsillectomy is reserved for recurrent abscess formation and should be deferred until the acute infection has resolved.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Tonsils and Throat. Midsagittal section of the upper aerodigestive tract showing the anatomical location of the palatine, pharyngeal (adenoid), and lingual tonsils relative to the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx. These lymphoid structures form the Waldeyer ring and are positioned to sample inhaled and ingested antigens

Blausen.com staff. Medical Gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine. doi: 10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)] via Wikimedia Commons.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Oral Cavity and Palatine Tonsils. View of the open mouth showing the anatomical relationships of the palatine tonsils, glossopalatine and pharyngopalatine arches, and surrounding oral structures. The isthmus faucium forms the oropharyngeal opening, bordered laterally by the palatine tonsils. Vallate and fungiform papillae are visible on the dorsal surface of the tongue.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Abulikemu N, Liu Z, Liu Y. Novel Findings on the Development and Immunological Functions of Palatine Tonsils. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2025 Jun 18:68(1):58. doi: 10.1007/s12016-025-09071-0. Epub 2025 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 40531272]

Arambula A, Brown JR, Neff L. Anatomy and physiology of the palatine tonsils, adenoids, and lingual tonsils. World journal of otorhinolaryngology - head and neck surgery. 2021 Jul:7(3):155-160. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2021.04.003. Epub 2021 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 34430822]

Jović M, Avramović V, Vlahović P, Savić V, Veličkov A, Petrović V. Ultrastructure of the human palatine tonsil and its functional significance. Romanian journal of morphology and embryology = Revue roumaine de morphologie et embryologie. 2015:56(2):371-7 [PubMed PMID: 26193201]

Carrillo-Ballesteros FJ, Oregon-Romero E, Franco-Topete RA, Govea-Camacho LH, Cruz A, Muñoz-Valle JF, Bustos-Rodríguez FJ, Pereira-Suárez AL, Palafox-Sánchez CA. B-cell activating factor receptor expression is associated with germinal center B-cell maintenance. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2019 Mar:17(3):2053-2060. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7172. Epub 2019 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 30783477]

Hagel JP, Bennett K, Buffa F, Klenerman P, Willberg CB, Powell K. Defining T Cell Subsets in Human Tonsils Using ChipCytometry. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 2021 Jun 15:206(12):3073-3082. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2100063. Epub 2021 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 34099545]

Stelter K. Tonsillitis and sore throat in children. GMS current topics in otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery. 2014:13():Doc07. doi: 10.3205/cto000110. Epub 2014 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 25587367]

Isaacson G, Parikh T. Developmental anatomy of the tonsil and its implications for intracapsular tonsillectomy. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2008 Jan:72(1):89-96 [PubMed PMID: 17996953]

Vlastarakos PV, Iacovou E. Spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage managed with emergency tonsillectomy in a 21-year-old man: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2013 Jul 26:7():192. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-192. Epub 2013 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 23890364]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTasli H, Ozen A, Akca ME, Karakoc O. Risk of internal carotid injury due to peritonsillar abscess drainage. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2020 Dec:47(6):1027-1032. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2020.06.001. Epub 2020 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 32580906]

Darrow DH, Siemens C. Indications for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. The Laryngoscope. 2002 Aug:112(8 Pt 2 Suppl 100):6-10 [PubMed PMID: 12172229]

Mistry D, Kelly G. Consent for tonsillectomy. Clinical otolaryngology and allied sciences. 2004 Aug:29(4):362-8 [PubMed PMID: 15270823]

Ramos SD, Mukerji S, Pine HS. Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2013 Aug:60(4):793-807. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.04.015. Epub 2013 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 23905820]

Bamgbose BO, Ruprecht A, Hellstein J, Timmons S, Qian F. The prevalence of tonsilloliths and other soft tissue calcifications in patients attending oral and maxillofacial radiology clinic of the university of iowa. ISRN dentistry. 2014:2014():839635. doi: 10.1155/2014/839635. Epub 2014 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 24587913]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSidell D, Shapiro NL. Acute tonsillitis. Infectious disorders drug targets. 2012 Aug:12(4):271-6 [PubMed PMID: 22338587]

Cereceda-Monteoliva N, Devabalan Y, Lorenz H, Magill JC, Unadkat S, Rennie C. Improving the management of suspected tonsillitis and peritonsillar abscess referred to ENT - a coronavirus disease 2019 service improvement. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2021 Jul:135(7):584-588. doi: 10.1017/S0022215121001213. Epub 2021 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 33913412]