Introduction

The tongue plays a critical role in human experience owing to its importance in speech, taste, chewing, swallowing, and sexual interaction.[1] Injuries to the tongue, therefore, may considerably impact quality of life. Tongue lacerations can result from a variety of means, including seizures, self-harm, blunt force facial trauma that causes a bite, penetrating trauma—such as a gunshot—and iatrogenic injuries of various types.[2][3][4] Intubated individuals having spinal stimulator surgery, for example, are at risk of tongue lacerations due to their prone positioning, allowing the tongue to fall between the teeth, coupled with the spinal stimulation triggering a biting response.[5] There have also been reported cases of tongue biting during electroconvulsive therapy and even self-mutilation of the tongue during psychotic episodes.[6][7] The use of electronic cigarettes has also occasionally led to explosions, causing intraoral trauma.[8] Careful evaluation for abuse should be performed in children without teeth who have a tongue laceration.[9] The management of tongue lacerations varies according to the severity of the injury, with some requiring complex surgical repair and others nothing more than close observation. The question of which tongue lacerations require repair and which can be healed by secondary intention remains a topic of debate.[10]

Most tongue lacerations occur on the anterior dorsum, followed by the mid-dorsum and anterior ventrum (see Image. Tongue Laceration).[11] Posterior tongue lacerations are less common given their location and the most common mechanisms of injury. Complete loss of tissue from the tip or lateral edge of the tongue leaves nothing to be repaired and is unlikely to cause a permanent deficit. After these injuries, the tongue will hypertrophy and obscure the deficit over time. Lacerations that result in significant bleeding or swelling can result in airway compromise and the need for endotracheal intubation, which makes them true emergencies.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

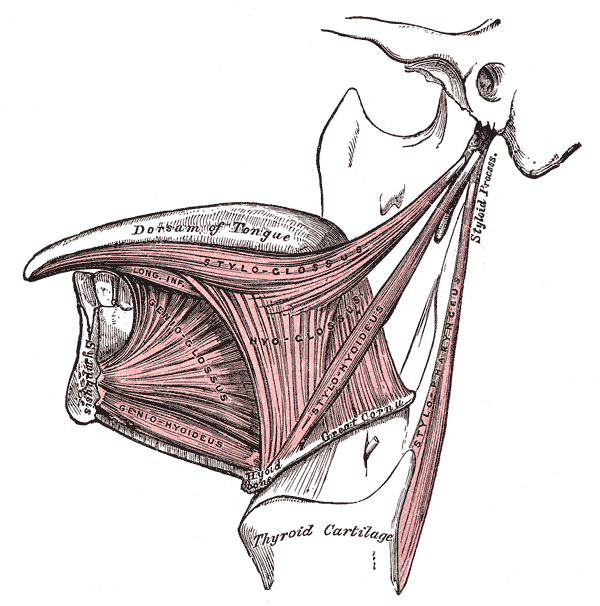

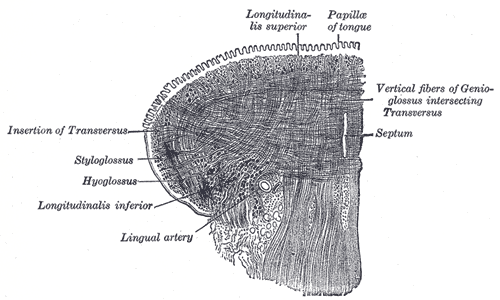

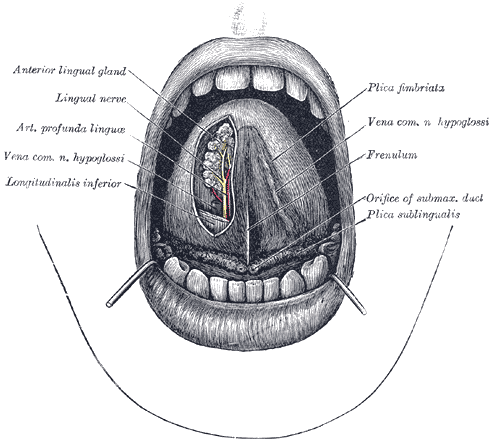

The tongue is a soft, muscular organ covered in mucosal epithelium, and it can sense taste via chemoreceptors and provide standard somatic sensation (see Image. The Mouth Cavity). The muscles of the tongue are divided into intrinsic and extrinsic groups. The intrinsic muscles are anchored exclusively within the tongue and change shape by contracting, lengthening, and maneuvering the tip. There are 4 intrinsic muscles: the vertical, transverse, and superior and inferior longitudinal muscles (see Image. The Mouth and Coronal Section of Tongue). The extrinsic muscles of the tongue originate from bony structures, including the genial tubercle of the mandible, the styloid process, and the hyoid bone. Four muscles comprise this group: the genioglossus, styloglossus, hyoglossus, and palatoglossus (see Image. The Mouth and Extrinsic Muscles of the Tongue). They allow the tongue to move around, protruding, retruding, elevating, and depressing.

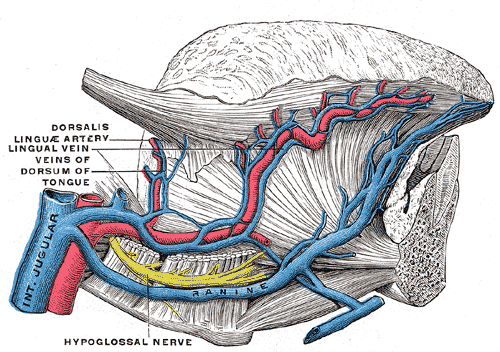

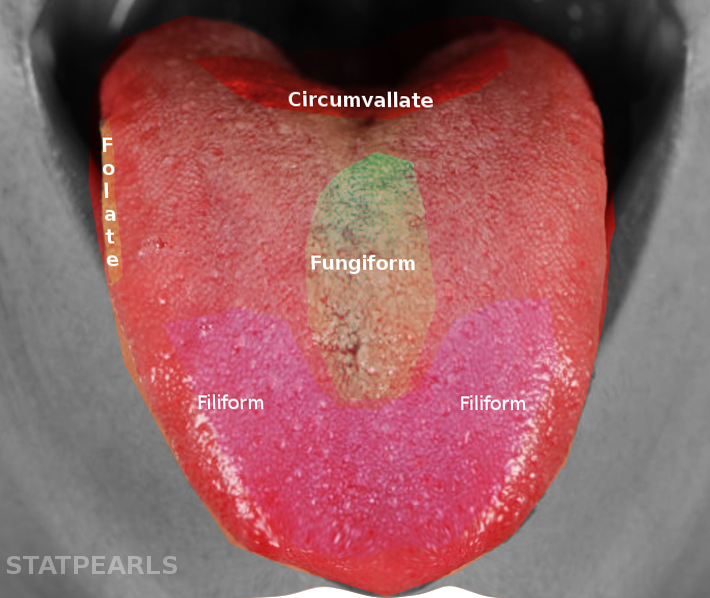

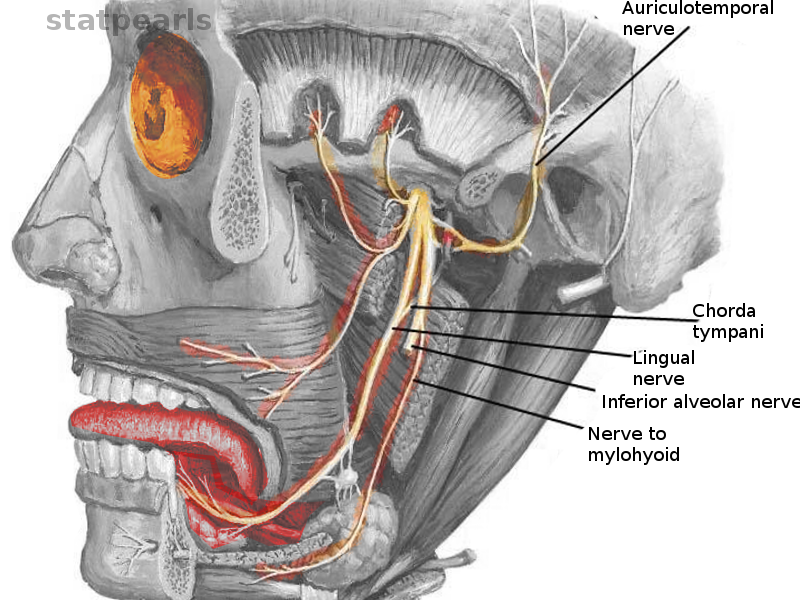

The hypoglossal nerve controls all 8 tongue muscles. Perfusion of the tongue is provided by the paired lingual arteries, which arise from the external carotid system, and venous drainage passes through the lingual veins into the internal jugular veins (see Image. Arteries and Veins of the Tongue). The lingual nerve carries somatic sensation from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, and taste sensation from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue is provided by the chorda tympani nerve, whose fibers join the lingual nerve in the infratemporal fossa and continue with them into the tongue itself (see Images. The Mouth Cavity and Chorda Tympani). Taste and somatic sensation from the posterior one-third of the tongue—the base of the tongue—are carried by the glossopharyngeal nerve. The chemoreceptors that provide taste sensation are housed within taste buds, distributed across the tongue's dorsum (see Image. Tongue Papillae and Taste Bud Distribution). For more information on tongue anatomy, please see Anatomy, Head and Neck, Tongue.

Indications

The decision to suture a tongue laceration depends on the size of the laceration and the degree to which the wound gapes open. The extent of the injury is most accurately assessed when the tongue is at rest inside the mouth. However, visualization of some parts may be improved with protrusion or lateral movement. Small, simple lacerations or avulsions can be left to heal without intervention due to the tongue’s ability to restore volume via hypertrophy.[12] Complex lacerations involve large flaps, active bleeding, or through-and-through defects, which are more likely to require surgical repair.

The Zurich Tongue Scheme, which was developed to guide decision-making for managing pediatric tongue lacerations, advises that repair should be performed for gaping lacerations on the tip of the tongue or gaping lacerations greater than 2 cm in length on the dorsum. Additionally, lacerations with active hemorrhage, tip of the tongue involvement, large flaps, or tissue loss affecting lingual function should be repaired primarily due to the increased risk of delayed wound healing or poor cosmetic outcomes. Other lacerations can be allowed to heal by secondary intention.[12][13] When more than one-quarter of the tongue's volume is lost, such as due to a gunshot wound, oncologic resection, or traumatic amputation, reconstructive surgery using a regional or free flap may be required to restore speech and swallowing function.[14] Given that there are no definitive standards for tongue laceration repair, the clinician should consider using shared decision-making regarding whether to repair simple tongue lacerations after a risk-benefit discussion with the patient or the parents/legal guardians, especially considering the potential need for general anesthesia in pediatric patients.

Contraindications

Contraindications for repair of tongue lacerations include a significant delay in presentation such that the tongue has already begun to heal secondarily, and lacerations that do not necessarily require closure, such as those that do not gape open at rest. Repair should also not be undertaken if the procedure would require equipment, expertise, or anesthesia that are not available. Repair of tongue lacerations may need to be delayed if other, life-threatening injuries need to be addressed first or if excessive edema prevents adequate access to the wound at the time of presentation.

Equipment

Required equipment may include the following:

- Suction: Yankauer or Goodhill

- Gauze

- Tongue depressor, Minnesota, or Weider (sweetheart) retractor

- Bite block

- Local anesthetic: lidocaine or bupivicaine with epinephrine

- Absorbable suture: 3-0, 4-0 chromic gut or polyglactin

- Needle driver: Halsey, Olsen-Hegar, or similar

- Suture scissors: Mayo, iris, or tenotomy

- Forceps: Gerald, DeBakey, or similar

- Microvascular instruments: vessel dilators, jeweler's forceps, Jacobson or Castroviejo needle driver, adventitial scissors, operating microscope, heparinized saline, Weck sponges, papaverine 30 mg/mL, venous couplers, 10-0 nylon suture

*Repair in children may also require procedural sedation or intranasal pain medications to facilitate the procedure.[12]

Personnel

A single clinician can repair a simple tongue laceration without assistance, but more complicated cases may require a nurse's assistance. If microvascular surgery is performed in the operating room, an anesthesia provider, a surgical technician, and a first assistant are also needed.

Preparation

Once wound assessment is complete and the decision is made to repair the laceration, it should be inspected for retained foreign bodies—specifically, broken teeth are a concern. If a tooth or a large portion cannot be located, a chest x-ray should be ordered to rule out aspiration into a lung. The wound should be irrigated thoroughly, and hemostasis should be achieved before repair.[11] If compromised due to bleeding or swelling, the patient's airway should be secured via intubation or tracheostomy before repair of the laceration, with nasotracheal intubation indicated if an orotracheal tube cannot be placed without obstructing access to the wound. Tracheostomy is rarely necessary in the absence of major facial trauma. The patient should receive appropriate pain medication or local anesthesia to facilitate the repair.

An inferior alveolar or lingual nerve block can anesthetize the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.[15] The inferior alveolar nerve is anesthetized with an injection of bupivacaine or another long-acting local anesthetic agent at a point between the coronoid notch of the mandible and the pterygomandibular raphe, above the occlusal plane of mandibular molars. However, a lingual nerve block may be more effective if placed 6 to 8 mm below the lingual gingival margin of the second mandibular molar. That said, extensive lacerations, avulsions, or amputation may require general anesthesia for repair by a specialist in the operating room. A piece of gauze can be used to hold the tongue outside the mouth, or a retention suture may be placed through the tongue and used for retraction during the repair. Suppose the tongue laceration is not the only injury the patient has sustained, such as in the context of a gunshot wound or motor vehicle accident. In that case, the most serious injuries should take priority according to the principles of advanced trauma life support. In these cases, securing the airway and briefly packing or suture ligating any active hemorrhage may be required to treat more pressing injuries first. The tongue laceration may be addressed definitively at a later time.

Technique or Treatment

The priority when managing a tongue laceration is ensuring airway patency, which may be compromised due to tongue edema, bleeding, dyscoordination due to nerve injury, or a combination thereof. More severe lacerations may require general anesthesia and intubation, or even tracheostomy, to permit adequate exposure of the injury and maintenance of the airway. The use of a laryngeal mask airway is discouraged, as it may not provide an effective seal against bleeding, and its caliber is typically larger than that of an endotracheal tube, thus making it more of an obstruction within the surgical field.

Most tongue lacerations are comparatively superficial, many of which need not be sutured. Superficial lacerations may be closed in a single layer with simple, interrupted sutures of 3-0 or 4-0 polyglactin or chromic gut. If the edges are irregular, as often, no debridement is necessary unless tissue is very obviously nonviable. When in doubt, more sutures should be placed, as the repair must withstand movement of the tongue; knots should not be tied too tightly, or edema that develops after the repair may cause strangulation of the wound edge. Deeper lacerations will require a layered closure to reapproximate any injured muscle, relieve tension, and eliminate dead space within which a hematoma or seroma could form; 3-0 polyglactin is most often used in a buried, interrupted fashion, taking care to consider the direction of muscle fibers when realigning the tissue (see Image. Dorsum of the Tongue With Transverse Partial-Thickness Laceration).[11] If sutures are placed, patients should be counseled that the free ends will feel like hairs in the mouth. This may be uncomfortable for a few days, until the stitches dissolve (see Image. Complete Repair Showing Appropriate Continuity of the Tongue).

The tongue is a highly vascular organ and tends to heal very well, although it may also bleed significantly if a major artery or vein is disrupted. Should this occur, ligation of the offending vessel with suture or titanium clips is appropriate, and collateral perfusion should suffice to support healing. Nerve injuries, on the other hand, should be repaired surgically if present. The hypoglossal and lingual nerves are located deep within the floor of the mouth and are, therefore, unlikely to be injured. If severed, these nerves must be reconstructed with microsurgical suturing of the epineurium to restore motor and sensory functionality.[16] In cases of substantial tissue loss, microvascular reconstructive surgery may be required. Successful tongue reimplantation with microsurgical reanastomosis of the lingual artery and vein has been reported several times in the literature, but this is predicated upon preservation of viable amputated tongue tissue.[1][17][18][19]

When no tissue is available for reimplantation, reconstruction with a regional flap, such as a submental artery island flap or a pectoralis major myocutaneous flap, or a microvascular free flap, such as a radial forearm flap or an anterolateral thigh flap, may be performed instead.[14] These procedures are highly technical, requiring specialized equipment and expertise, and are generally performed by plastic surgeons or otolaryngologists. Suppose anesthesia is not feasible and sutures cannot be placed. In that case, successful use of cyanoacrylate skin glue has been reported for wound approximation, despite its lack of approval for use on oral mucosa. A piece of gauze may dry and hold the tongue, and additional pressurized air may be applied to dry the tongue immediately before glue application. This technique is most appropriate for a comparatively simple wound, such as one located on the dorsum of the tongue, rather than an edge or the tip.[20]

Complications

Because tongue lacerations can cause functional deficits, failing to repair them appropriately may result in the persistence of the same problems. Additionally, some complications may occur as sequelae of treatment. Repairing tongue lacerations with nonabsorbable suture may cause granulomas due to foreign body reactions. As with all laceration repairs, there is also the potential to develop a noticeable scar, which is possible in patients who heal by secondary intention.[12] The risk of infection in tongue lacerations is fairly low, and the use of antibiotics is controversial; no clear guidelines for their prophylactic use currently exist.[21][22] A review of 154 cases reported that no infections developed, even with preventative antibiotics rarely being prescribed.[23]

Factors that may support the use of prophylactic antibiotics include an immunocompromised state, heavily contaminated wounds, and delayed closure. Drugs of choice should cover oral flora, predominantly gram-positive and anaerobic organisms.[24] An alternative option is chlorhexidine mouthwash to lower the infection risk. Other complications include swelling, impaired speech and swallowing, or even difficulty breathing if edema or hemorrhage is significant. Substantial active bleeding or swelling may necessitate endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy for airway protection. Similarly, development of a hematoma after closure of a tongue laceration may require advanced airway management, immediate reopening of the wound, evacuation of the blood, and establishment of hemostasis.

Clinical Significance

Tongue lacerations occur in all age groups, from children to older adults, owing to the many mechanisms by which these injuries are caused. Whether to repair a tongue laceration or allow it to close by secondary intention remains a decision to be made on a case-by-case basis. Most tongue lacerations will heal satisfactorily without intervention, although more complex wounds and tissue defects necessitate specialty consultation. The Zurich Tongue Scheme guides clinicians when considering which wound features are most likely to benefit from suture closure and which lacerations can achieve satisfactory outcomes without intervention.[12]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

From minor lacerations to amputation, the repair of tongue injuries requires a range of abilities and specialties to achieve optimal results. While simple lacerations may be closed by emergency department clinicians, dentists, or primary care clinicians, more complex wounds will require the expertise of specialists such as otolaryngologists, plastic surgeons, oral surgeons, and anesthesiologists. Lacerations in children may require procedural sedation or general anesthesia for closure of even comparatively simple injuries. Social workers or case management coordinators may also have a role in situations where child abuse is suspected.[9] The lack of large studies comparing repair techniques makes communication among clinicians to establish a plan of care based on past experiences a critical part of the interprofessional team approach to each new patient with a tongue laceration.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Arteries and Veins of the Tongue. This image shows the internal jugular vein, dorsalis linguae artery, lingual vein, veins of the dorsum of the tongue, and hypoglossal nerve.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Mouth and Extrinsic Muscles of the Tongue. This image shows the left dorsum side of the tongue, along with the styloglossus, hyoglossus, genioglossus, geniohyoideus, stylopharyngeus, and thyroid cartilage.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Mouth and Coronal Section of the Tongue. This image demonstrates the intrinsic muscles of the tongue, including the insertion of the transversus, styloglossus, hyoglossus, longitudinalis inferior, longitudinalis superior, and the vertical fibers of the genioglossus intersecting the transversus, along with the lingual artery, papillae of the tongue, and the septum.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Tongue Papillae and Taste Bud Distribution. The tongue contains 4 papillae: the circumvallate papillae are arranged in a V-shape at the posterior tongue; the foliate papillae are located along the lateral margins; the fungiform papillae are scattered mainly on the anterior dorsal surface; and the filiform papillae are distributed across the anterior two-thirds, providing mechanical but not gustatory function.

Contributed by S Bhimji, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Dorsum of the Tongue With Transverse Partial-Thickness Laceration. This laceration involves three-quarters of the cross-sectional area of the tongue located at the union of its medial and proximal thirds.

Hernández-Méndez JR, Rodríguez-Luna MR, Guarneros-Zárate JE, Vélez-Palafox M. Traumatic partial amputation of the tongue. Case report and literature review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2015;29(5):110-113. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2015.12.049.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Complete Repair Showing Appropriate Continuity of the Tongue. If sutures are placed, patients should be counseled that the free ends will feel like hairs in the mouth. This may be uncomfortable for a few days until the stitches dissolve.

Hernández-Méndez JR, Rodríguez-Luna MR, Guarneros-Zárate JE, Vélez-Palafox M. Traumatic partial amputation of the tongue. Case report and literature review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2015;29(5):110-113. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2015.12.049.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Mouth Cavity. In this image, the apex of the tongue is turned upward; also shown are the interior lingual gland, lingual nerve, arterial profunda linguae, vena common hypoglossi nerve, longitudinalis inferior, plica fimbriata, frenulum, and plica sublingualis.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Mouth Cavity and Chorda Tympani. The lingual nerve carries somatic sensation from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, and taste sensation from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue is provided by the chorda tympani nerve, whose fibers join the lingual nerve in the infratemporal fossa and continue with them into the tongue itself.

Contributed by O Chaigasame, MD

References

Kim JS, Choi TH, Kim NG, Lee KS, Han KH, Son DG, Kim JH, Lee SI, Kang D. The replantation of an amputated tongue by supermicrosurgery. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2007:60(10):1152-5 [PubMed PMID: 17368124]

George CLS, Theesfeld SSN, Wang Q, Hudson MJ, Harper NS. Identification and Characterization of Oral Injury in Suspected Child Abuse Cases: One Health System's Experience. Pediatric emergency care. 2021 Oct 1:37(10):494-497. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001715. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30601344]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBeena JP. Management of tongue and lip laceration due to dystonia in a 1-year-old infant. Journal of the Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry. 2017 Jan-Mar:35(1):90-93. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.199223. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28139490]

Costacurta M, Benavoli D, Arcudi G, Docimo R. Oral and dental signs of child abuse and neglect. ORAL & implantology. 2015 Apr-Sep:8(2-3):68-73. doi: 10.11138/orl/2015.8.2.068. Epub 2016 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 27555907]

Meco BC, Aytug S, Baskan EB, Meco C. Can tongue laceration caused by intraoperative neuromonitoring during spinal surgery in the prone position be prevented?: Assessment of a new management protocol which includes placement of a silicone dental guard. European journal of anaesthesiology and intensive care. 2023 Oct:2(5):e0033. doi: 10.1097/EA9.0000000000000033. Epub 2023 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 39916812]

Woo SW, Do SH. Tongue laceration during electroconvulsive therapy. Korean journal of anesthesiology. 2012 Jan:62(1):101-2. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2012.62.1.101. Epub 2012 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 22323965]

Hong JM, Eun SC. Self-mutilation of the tongue in a patient with schizophrenia. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2014:25(2):e116-8. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000000447. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24621750]

Vaught B, Spellman J, Shah A, Stewart A, Mullin D. Facial trauma caused by electronic cigarette explosion. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2017 Mar:96(3):139-142 [PubMed PMID: 28346645]

Bernstein JD, Kruczek S, Laub N, Carvalho D. Extensive Tongue Laceration in an Edentulous Infant: Is It Child Abuse? Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2025 Mar:104(1_suppl):362S-365S. doi: 10.1177/01455613221149803. Epub 2023 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 36637022]

Lamell CW, Fraone G, Casamassimo PS, Wilson S. Presenting characteristics and treatment outcomes for tongue lacerations in children. Pediatric dentistry. 1999 Jan-Feb:21(1):34-8 [PubMed PMID: 10029965]

Das UM, Gadicherla P. Lacerated tongue injury in children. International journal of clinical pediatric dentistry. 2008 Sep:1(1):39-41. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1007. Epub 2008 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 25206087]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSeiler M, Massaro SL, Staubli G, Schiestl C. Tongue lacerations in children: to suture or not? Swiss medical weekly. 2018 Oct 22:148():w14683. doi: 10.4414/smw.2018.14683. Epub 2018 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 30378089]

Seiler M, Schiestl C. [Tongue Lacerations in Children. The Zurich Tongue Scheme]. Praxis. 2022 Dec:111(16):922-926. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a003944. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36475366]

Vincent A, Kohlert S, Lee TS, Inman J, Ducic Y. Free-Flap Reconstruction of the Tongue. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2019 Feb:33(1):38-45. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1677789. Epub 2019 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 30863211]

Balasubramanian S, Paneerselvam E, Guruprasad T, Pathumai M, Abraham S, Krishnakumar Raja VB. Efficacy of Exclusive Lingual Nerve Block versus Conventional Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block in Achieving Lingual Soft-tissue Anesthesia. Annals of maxillofacial surgery. 2017 Jul-Dec:7(2):250-255. doi: 10.4103/ams.ams_65_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29264294]

Kang AS, Kang KS. Traumatic bifid tongue: A rare presentation in a child. Case report. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2020 Sep:57():11-13. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.06.040. Epub 2020 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 32695333]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEgozi E, Faulkner B, Lin KY. Successful revascularization following near-complete amputation of the tongue. Annals of plastic surgery. 2006 Feb:56(2):190-3 [PubMed PMID: 16432330]

Buntic RF, Buncke HJ. Successful replantation of an amputated tongue. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1998 May:101(6):1604-7 [PubMed PMID: 9583492]

Davis C, Armstrong J. Replantation of an amputated tongue. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2001 Oct:108(5):1441-2 [PubMed PMID: 11604659]

Kazzi MG, Silverberg M. Pediatric tongue laceration repair using 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (dermabond(®)). The Journal of emergency medicine. 2013 Dec:45(6):846-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.05.004. Epub 2013 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 23827167]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSteele MT, Sainsbury CR, Robinson WA, Salomone JA 3rd, Elenbaas RM. Prophylactic penicillin for intraoral wounds. Annals of emergency medicine. 1989 Aug:18(8):847-52 [PubMed PMID: 2502938]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMark DG, Granquist EJ. Are prophylactic oral antibiotics indicated for the treatment of intraoral wounds? Annals of emergency medicine. 2008 Oct:52(4):368-72 [PubMed PMID: 18819178]

Gonsalves CL, Zhu JW, Kim GY, Leveille CF, Kam AJ. Surgical versus conservative management of tongue lacerations in the acute care setting: A systematic review of the literature. Paediatrics & child health. 2022 Mar:27(1):32-42. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxab044. Epub 2021 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 35273669]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceArmstrong BD. Lacerations of the mouth. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2000 Aug:18(3):471-80, vi [PubMed PMID: 10967735]