Introduction

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is a rare, unilateral idiopathic granulomatous inflammatory disease affecting the cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure, or orbit. The condition presents with severe ocular pain and ophthalmoplegia due to paresis of cranial nerves III, IV, or VI. The syndrome falls within the spectrum of idiopathic orbital inflammatory diseases, a group that also includes orbital pseudotumor.[1] As Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is idiopathic, other causes of painful ophthalmoplegia, such as vasculitis, meningitis, neoplasm, sarcoidosis, and orbital pseudotumor, must be excluded.[2]

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome was first described in 1954 by Dr Eduardo Tolosa, a Spanish neurosurgeon.[3] Similar cases were reported by Hunt et al in 1961.[4] The term Tolosa-Hunt syndrome was first introduced by Smith and Taxdal in 1966.[5] Smith and Taxdal described a dramatic response to steroid therapy. This steroid responsiveness is used as a diagnostic marker, yet it also becomes a common cause for misdiagnosis.

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is one of the rare disorders recognized by the National Organisation for Rare Disorders. The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3 beta) defines Tolosa-Hunt syndrome as unilateral orbital pain accompanied by paresis of one or more of the third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves, attributed to granulomatous inflammation confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or biopsy.[6] Subsequent case series using the ICHD-3 beta diagnostic criteria demonstrated a high percentage of false-negative and false-positive cases, making the diagnostic criteria less helpful.[7] With other underlying causes of painful ophthalmoplegia being identified, such as lymphoma, infections, vasculitis, and other noninfectious orbital inflammatory disorders, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa, sarcoidosis, and IgG-4-related disease, fewer cases of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome are diagnosed. A thorough diagnostic evaluation remains essential to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is idiopathic by definition and is the result of nonspecific chronic granulomatous inflammation in the region of the cavernous sinus or superior orbital fissure. However, traumatic injury, tumors, or an aneurysm could be the potential triggers. As more underlying causes of painful ophthalmoplegia are identified, such as lymphoma, infections, vasculitis, and noninfectious orbital inflammatory disorders including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa, sarcoidosis, and IgG-4–related disease, the number of cases diagnosed as Tolosa-Hunt syndrome has declined.[1]

Epidemiology

The estimated annual incidence of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is approximately 1 case per million.[8] Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is found worldwide without any geographical or racial preponderance. This condition is uncommon in young individuals. The average age of onset is 41 years, according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders. Although typically unilateral, either side can be affected, and there have been case reports about bilateral involvement (approximately 5%). There is no male-female predisposition.[9]

Pathophysiology

As previously noted, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is caused by nonspecific granulomatous inflammation of unknown etiology. In his initial report, Dr Eduardo Tolosa described the pathophysiology as nonspecific, chronic inflammation of the septa and wall of the cavernous sinus with the proliferation of fibroblasts and an infiltration with lymphocytes and plasma cells.[3] Hunt et al agreed with the above observation and added that such inflammatory changes, in a tight connective tissue, may exert pressure upon the penetrating nerves.[4] These affected nerves commonly include cranial nerves III, IV, and VI, and the superior division of the fifth cranial nerve. Further studies showed the presence of granulomatous material deposits along with epitheloid cells and giant cells. Although rare, necrosis has been observed occasionally. There is also associated thickening of the dura mater within the cavernous sinus.

Inflammation in the cavernous sinus region has rarely been associated with intracranial inflammation; however, systemic inflammation has not been reported to date.[8] Although no definitive autoimmune etiology has been established, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome has been reported in association with systemic and autoimmune inflammatory conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and Wegener's granulomatosis. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome can be a presenting symptom of these diseases. However, once the underlying condition is diagnosed, the final diagnosis cannot be Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome.[10][11] Similarly, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome cannot be caused by any infectious agent.

History and Physical

The hallmark of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is painful ophthalmoplegia. The pain is typically sharp, shooting, stabbing, boring, severe, and intense. The pain is typically localized to the periorbital region but can often be retro-orbital, extending into the frontal and temporal areas. Pain tends to be the presenting symptom and can precede ophthalmoplegia by up to 30 days. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome tends to have a relapsing and remitting course, with attacks recurring every few months or years. Other features include involvement of all 3 ocular motor nerves—oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerves—in different combinations, leading to ophthalmoplegia. The ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve is commonly affected. The oculomotor nerve is most commonly involved (approximately 80%), followed by the abducens nerve (approximately 70%), an ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (approximately 30%), and the trochlear nerve (approximately 29%).[8] In addition, sympathetic involvement, such as third-order neuron Horner syndrome (in approximately 20% of cases) or parasympathetic (oculomotor nerve) involvement can occur, leading to pupillary abnormalities.[12][13]

There are reports of involvement of the maxillary and mandibular divisions of the fifth cranial nerve (trigeminal), optic nerve, and facial nerve, suggesting an extension of the disease process beyond the cavernous sinus.[5][4][14][15][16] Rarely, inflammation can involve the orbital apex, leading to optic nerve damage and consequent optic disc pallor or swelling. Loss of visual acuity in such cases is unpredictable and can be permanent.[17]

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome typically does not have any other neurological or systemic involvement.[8] Some studies have reported nausea and vomiting, which are probably due to the severe pain the patient experienced by the patient, and these symptoms usually resolve with effective pain management. Chronic fatigue is also reported. If left untreated, symptoms of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome can last up to 8 weeks but often resolve spontaneously afterward. There are seldom any residual neurological deficits.[18]

Evaluation

The differential diagnosis of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome includes all causes of painful ophthalmoplegia and, therefore, is exceptionally broad. A thorough diagnostic workup is necessary to exclude other etiologies before diagnosing Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, and long-term clinical monitoring is required to ensure remission and rule out alternative diagnoses.[19] Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is generally diagnosed based on the clinical presentation of painful ophthalmoplegia and neuroimaging studies to rule out other causes and response to steroids. Laboratory tests and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies are supportive tests but help rule out other causes of ophthalmoplegia. Tissue biopsy is a diagnostic procedure, but it is considered the procedure of last resort and is rarely performed due to its high risks and technical difficulties.[20]

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is also included in the International Headache Society (IHS) classification ICHD-3 beta, under part three, within the section on painful cranial neuropathies and other facial pains. The IHS lays down diagnostic criteria for Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, which have high sensitivity (approximately 95%-100%) but low specificity (approximately 50%).[21] The criteria are summarized as follows:

- Unilateral headache

- Includes both of the following:

- Presence of granulomatous inflammation of the cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure, or orbit, as observed on MRI or biopsy

- Palsy of one or more of the oculomotor nerves (cranial nerves III, IV, and VI) on the same side

- Corroboration of the cause as evidenced by both of the following:

- Palsies of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI have followed a headache in 2 weeks or less, or have developed simultaneously with a headache

- Localization of a headache around the eye on the same side

- Not better explained by any other headache etiology

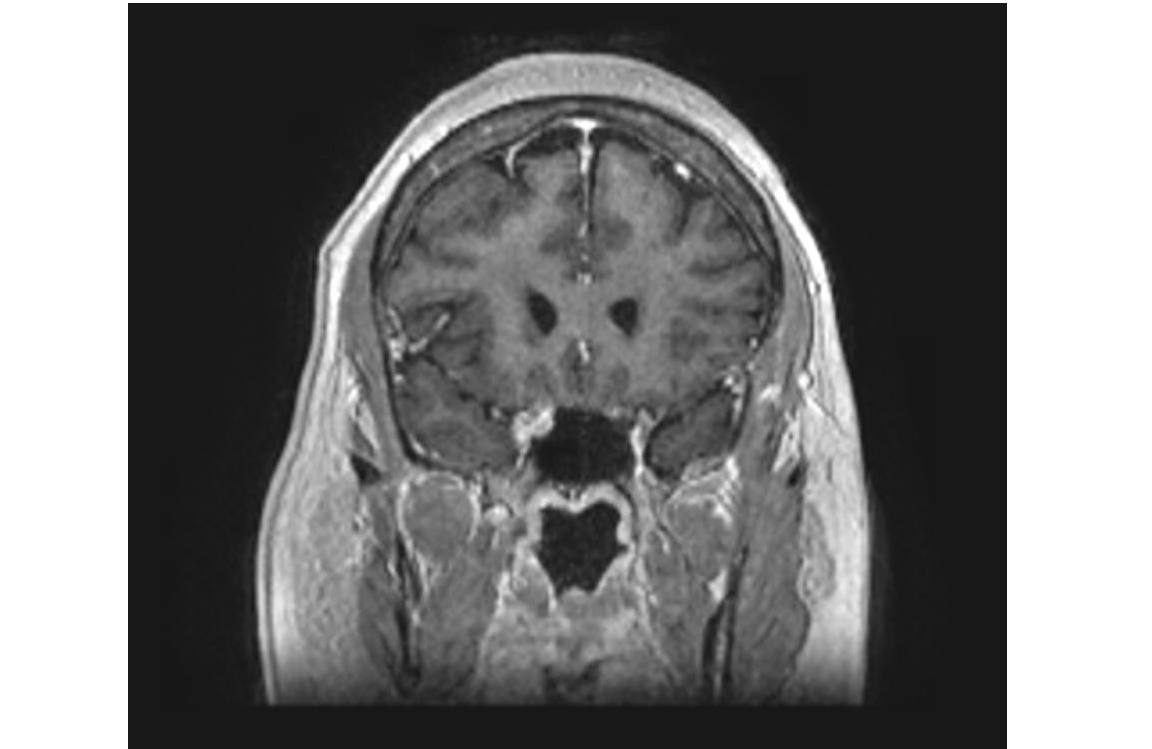

Neuroimaging

MRI brain with contrast, especially the coronal view, is a crucial diagnostic study. This technique helps exclude other disease processes that produce painful ophthalmoplegia, as it is rarely normal in cases of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. MRI can show thickening of the cavernous sinus because of abnormal soft tissue, which is isointense on T1, iso- or hypointense on T2, and enhances with contrast. Other MRI findings include convexity of the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus and extension into the orbital apex. High-resolution computed tomography can also reveal changes in soft tissue, but it lacks sensitivity. Thus, MRI should be performed for better visualization of the region of the cavernous sinus and superior orbital fissure. MRI findings have low specificity, and the aforementioned findings can also be observed in other conditions, such as lymphoma, meningioma, and sarcoidosis.[9] Vascular abnormalities in the intracavernous segment of the carotid artery, such as segmental narrowing, constriction, and irregularities, have been reported. These changes can be detected through MR angiography, CT angiography, and digital subtraction angiography, and typically resolve with steroids.

Other Tests

When there is suspicion of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome on clinical presentation and MRI, blood and CSF studies should be performed to rule out other causes of painful ophthalmoplegia, as Tolosa-Hunt syndrome remains a clinical diagnosis of exclusion.[9] Blood tests include complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, HbA1C, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, angiotensin-converting enzyme, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-nuclear cytoplasmic antibody, anti–double-standed DNA antibody, Anti-smooth muscle antibody, Lyme panel, serum protein electrophoresis, and fluorescent treponemal antibody test. CSF studies include glucose, protein, cell count and differential, cytology, culture and Gram stain, angiotensin-converting enzyme, syphilis, and Lyme serology. Blood and CSF studies are expected to be normal in cases of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, except for some mild increase in mononuclear cell count and elevated protein in the CSF. If other abnormalities are found, another diagnosis should be considered.

Glucocorticoid Response

Glucocorticoid responsiveness plays a key role in both the diagnosis and treatment of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. Treating with high doses of systemic steroids leads to a dramatic improvement in pain within 2 to 3 days. Cranial nerve dysfunction improves, and there is a reduction in abnormal tissue volume and signal intensity on MRI over the next few weeks of steroid treatment.[12] Reduction in pain helps confirm the diagnosis and is further supported by cranial nerve dysfunction improvement and resolution of MRI findings. However, caution should be exercised when confirming the diagnosis of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome with a steroid response, as clinical and radiologic improvement is known to occur with other disease processes, such as malignancies, infections, or vasculitis.[16]

Diagnosing Tolosa-Hunt syndrome in children and adolescents is particularly challenging due to its rarity and the complexity of symptoms. A high index of clinical suspicion and prompt steroid therapy are crucial in these patients.[22]

Treatment / Management

Glucocorticoids have been the mainstay of the treatment ever since the syndrome was first described.[4][5] However, there is no specific data to provide recommendations on dose, duration, or route of administration.[9] Spontaneous remission of symptoms is known to occur. Although orbital pain drastically improves with steroid treatment, there is no evidence to suggest cranial nerve palsies improve faster with it. As with any glucocorticoid regimen, treatment for Tolosa-Hunt syndrome involves initial high-dose therapy for a few days followed by a gradual taper over weeks to months.[23] Symptom resolution guides the degree and rapidity of the taper. Follow-up imaging studies, such as MRI, can be repeated; however, they typically lag behind symptomatic improvement by a few weeks.(B3)

A very small percentage of patients require immunosuppression with other agents, either to avoid the adverse effects of long-term steroid therapy or for long-term suppression of the disease process itself. Azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, and infliximab have been used as second-line therapy. Radiotherapy has also been reported as a second-line therapy for recurrent flare-ups leading to steroid dependence or as a first-line therapy in the presence of contraindications to steroids. Typically, these patients have had a biopsy-proven diagnosis of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome before a second-line therapy is initiated.[7](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome includes all causes of painful ophthalmoplegia and, therefore, is exceptionally broad. These conditions can be classified into 4 major categories—trauma, neoplasm, vascular, and inflammatory. Inflammation may be infectious and noninfectious. A comprehensive diagnostic workup is necessary to exclude other etiologies before diagnosing Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, and long-term clinical monitoring is required to ensure remission and rule out alternative diagnoses.[19] The following is a list of differential diagnoses:

- Benign skull tumors

- Orbital and retro-orbital metastases

- Cavernous sinus syndrome

- Cerebral aneurysm

- Cerebral venous thrombosis

- Lyme disease

- Meningioma

- Neurosarcoidosis

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Primary central nervous system lymphoma

- Primary malignant skull tumors

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Tuberculous meningitis

- Varicella zoster virus

Prognosis

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is characterized by the dramatic symptomatic improvement following glucocorticoid therapy. Symptom improvement, particularly pain relief, is typically observed 24 to 72 hours after initiating steroids, with the majority of patients experiencing improvement within 1 week. Cranial nerve palsies improve gradually, with recovery taking anywhere from 2 to 8 weeks.[5] Residual neurological deficits after steroid treatment are rare.

Relapses tend to occur in about 40% to 50% of patients and can be ipsilateral, contralateral, or bilateral.[4] Relapses are more common in younger patients compared to older patients. Every relapse should ideally be investigated with a full workup, as Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion.[16] The role of corticosteroids in preventing relapses remains uncertain.[24]

Complications

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is typically nonfatal and often self-limiting. Prompt treatment with high-dose steroids limits most of the complications. The primary complications include permanent neurological deficits secondary to involvement of cranial nerves III, IV, or VI, resulting in ophthalmoplegia. Visual impairment may occur rarely due to optic nerve involvement. Relapses are common and may require prolonged steroid therapy, increasing the risk of long-term steroid-related complications such as hyperglycemia, diabetes mellitus, adrenal suppression, electrolyte disturbances, osteoporosis, and chronic immunosuppression.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Although Tolosa-Hunt syndrome has defined diagnostic criteria, it remains a diagnosis of exclusion. A comprehensive diagnostic workup is necessary to rule out other diagnoses in any patient clinically diagnosed with Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. Steroid responsiveness is not specific to Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, and patients must be educated to understand that they require long-term monitoring and imaging to ensure remission.

Pearls and Other Issues

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is clinically characterized as a painful, idiopathic, steroid-responsive ophthalmoplegia with specific diagnostic criteria. This syndrome is a granulomatous inflammatory disease centered in the cavernous sinus and extending towards the orbit. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome has recently been placed under an umbrella diagnosis of idiopathic orbital inflammatory diseases, including the entity of orbital pseudotumor. Despite having established diagnostic criteria, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Steroid responsiveness is not specific to Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, and patients require long-term monitoring and imaging to ensure remission.[25]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Primary care providers, nurse practitioners, and internists often encounter patients presenting with headaches. However, when they encounter a patient with a severe headache and ophthalmoplegia, a referral to a neurologist is necessary. Unlike typical headaches, patients with Tolosa-Hunt syndrome are treated with steroids and immunosuppressive agents. Despite treatment, recurrences are common, and the overall quality of life is poor. When patients are treated with steroids, the nurse practitioner and primary care provider should monitor the patient for adverse effects. An interdisciplinary approach to managing this disease yields optimal patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Yu S, Chen T. Pearls & Oy-sters: Idiopathic Orbital Inflammation and Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome With Intracranial Extension. Neurology. 2023 Aug 22:101(8):371-374. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207368. Epub 2023 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 37185126]

Kim H, Oh SY. The clinical features and outcomes of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. BMC ophthalmology. 2021 May 27:21(1):237. doi: 10.1186/s12886-021-02007-0. Epub 2021 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 34044807]

TOLOSA E. Periarteritic lesions of the carotid siphon with the clinical features of a carotid infraclinoidal aneurysm. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1954 Nov:17(4):300-2 [PubMed PMID: 13212421]

HUNT WE, MEAGHER JN, LEFEVER HE, ZEMAN W. Painful opthalmoplegia. Its relation to indolent inflammation of the carvernous sinus. Neurology. 1961 Jan:11():56-62 [PubMed PMID: 13716871]

Smith JL, Taxdal DS. Painful ophthalmoplegia. The Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. American journal of ophthalmology. 1966 Jun:61(6):1466-72 [PubMed PMID: 5938314]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhang X, Zhou Z, Steiner TJ, Zhang W, Liu R, Dong Z, Wang X, Wang R, Yu S. Validation of ICHD-3 beta diagnostic criteria for 13.7 Tolosa-Hunt syndrome: Analysis of 77 cases of painful ophthalmoplegia. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache. 2014 Jul:34(8):624-32. doi: 10.1177/0333102413520082. Epub 2014 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 24477599]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMullen E, Rutland JW, Green MW, Bederson J, Shrivastava R. Reappraising the Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome Diagnostic Criteria: A Case Series. Headache. 2020 Jan:60(1):259-264. doi: 10.1111/head.13692. Epub 2019 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 31681980]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIaconetta G, Stella L, Esposito M, Cappabianca P. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome extending in the cerebello-pontine angle. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache. 2005 Sep:25(9):746-50 [PubMed PMID: 16109058]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKline LB, Hoyt WF. The Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2001 Nov:71(5):577-82 [PubMed PMID: 11606665]

Calistri V, Mostardini C, Pantano P, Pierallini A, Colonnese C, Caramia F. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. European radiology. 2002 Feb:12(2):341-4 [PubMed PMID: 11870431]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTrobe JD, Hood CI, Parsons JT, Quisling RG. Intracranial spread of squamous carcinoma along the trigeminal nerve. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1982 Apr:100(4):608-11 [PubMed PMID: 7073576]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCakirer S. MRI findings in Tolosa-Hunt syndrome before and after systemic corticosteroid therapy. European journal of radiology. 2003 Feb:45(2):83-90 [PubMed PMID: 12536085]

de Arcaya AA, Cerezal L, Canga A, Polo JM, Berciano J, Pascual J. Neuroimaging diagnosis of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome: MRI contribution. Headache. 1999 May:39(5):321-5 [PubMed PMID: 11279911]

Tessitore E, Tessitore A. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome preceded by facial palsy. Headache. 2000 May:40(5):393-6 [PubMed PMID: 10849035]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSondheimer FK, Knapp J. Angiographic findings in the Tolosa-Hunt syndrome: painful ophthalmoplegia. Radiology. 1973 Jan:106(1):105-12 [PubMed PMID: 4682706]

Förderreuther S, Straube A. The criteria of the International Headache Society for Tolosa-Hunt syndrome need to be revised. Journal of neurology. 1999 May:246(5):371-7 [PubMed PMID: 10399869]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKaye AH, Hahn JF, Craciun A, Hanson M, Berlin AJ, Tubbs RR. Intracranial extension of inflammatory pseudotumor of the orbit. Case report. Journal of neurosurgery. 1984 Mar:60(3):625-9 [PubMed PMID: 6699710]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTsirigotaki M, Ntoulios G, Lioumpas M, Voutoufianakis S, Vorgia P. Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome: Clinical Manifestations in Children. Pediatric neurology. 2019 Oct:99():60-63. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.02.013. Epub 2019 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 30982655]

Lueck CJ. Time to retire the Tolosa-Hunt syndrome? Practical neurology. 2018 Oct:18(5):350-351. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2018-001951. Epub 2018 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 29848513]

Qasim B, Siddiqui F, Saleem M, Zohaib M, Khan MK, Siyal NA. Clinical presentation and management of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome: a case report. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2025 Jan:75(1):115-118. doi: 10.47391/JPMA.10593. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39828842]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHeadache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache. 2013 Jul:33(9):629-808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23771276]

Ahmed HS, Jayaram PR, Khar S. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Headache. 2025 Jun:65(6):1027-1040. doi: 10.1111/head.14890. Epub 2025 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 39749480]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSugano H, Iizuka Y, Arai H, Sato K. Progression of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome to a cavernous dural arteriovenous fistula: a case report. Headache. 2003 Feb:43(2):122-6 [PubMed PMID: 12558766]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWiener J, Cron RQ. Successful treatment of pediatric Tolosa-Hunt syndrome with adalimumab. European journal of rheumatology. 2020 Feb:7(Suppl1):S82-S84. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2019.19149. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31804175]

Chen JJ. Don't Forget the Oy-sters When It Comes to Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome. Neurology. 2023 Aug 22:101(8):337-338. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207450. Epub 2023 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 37185125]