Introduction

The temporoparietal fascia flap (TPFF) is a versatile flap that is frequently employed in the reconstruction of craniofacial defects requiring thin, pliable, and well-vascularized tissue that can support skin grafting (see Image. Temporoparietal Fascia Flap).[1][2][3] The TPFF is commonly transferred pedicled to repair the scalp, auricle, facial soft tissue, orbit, oral cavity, nasopharynx, and skull base defects.[4]

This flap is considered an axial flap because it contains the superficial temporal artery within it, which allows it to provide up to a 14 x 17 cm sheet of soft tissue; however, the flap may even be elevated with its overlying scalp, making it particularly useful for defects of hair-bearing regions.[5] If more substantial reconstruction is required, the TPFF may be harvested, combined, or chimeric with deep temporal fascia, temporalis muscle, or subjacent calvarial bone.[6][7] When harvested for free microvascular anastomosis based on the superficial temporal artery and vein, the TPFF can be applied to various extremity reconstructions, particularly in the hands and feet.[8]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

To increase the chances of harvesting a viable TPFF, it is critical to understand the relevant anatomy.[2] The layers (from superficial to deep) potentially encountered during harvest of the TPFF include:

- Skin

- Subcutaneous tissue

- Temporoparietal fascia (within which the temporoparietalis muscle may be encountered)

- Loose areolar tissue

- Superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia

- Temporalis muscle

- Deep layer of the deep temporal fascia

- Pericranium

- Bone (temporal, parietal, frontal, greater wing of sphenoid)

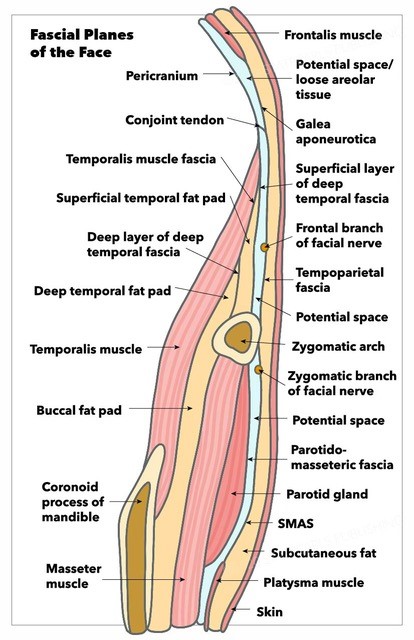

The temporoparietal fascia is a thin layer of connective tissue lying below the level of the subcutaneous adipose tissue but superficial to the temporalis muscle fascia.[9] The temporoparietal fascia is anchored superiorly along the temporal line at the fascial condensation known as the conjoint tendon. Medial to the conjoint tendon, the plane of the temporoparietal fascia is occupied by the galea aponeurotica, with the frontalis muscle anteriorly and the occipitalis muscle posteriorly. Inferiorly, the temporoparietal fascia condenses with the periosteum of the zygomatic arch, below which the plane becomes the superficial musculoaponeurotic system of the face (see Image. Fascial Planes of the Face).[10] This relationship is relevant not only because it defines the extent of the soft tissue that can be harvested as a TPFF, but also because branches of the facial nerve consistently run deep to this plane and should be preserved during surgery.

The alternative nomenclature of the temporoparietal fascia—the superficial temporal fascia—is potentially confusing when juxtaposed to the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia, which invests the superficial surface of the superficial temporal fat pad. The temporalis muscle fascia, which can be used for free grafts or vascularized flaps, is also known as the deep temporal fascia. This fascia splits into deep and superficial layers to surround the superficial temporal fat pad that sits on the lateral surface of the temporalis muscle above the zygomatic arch. The superficial temporal fat pad and the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia then end on the superior aspect of the zygomatic arch, condensing with the temporoparietal fascia and the zygomatic arch periosteum. The deep layer of the deep temporal fascia continues medially and inferior to the zygomatic arch to invest the deep temporal fat pad, which sits on the lateral aspect of the temporalis muscle medial and inferior to the zygomatic arch (see Image. Fascial Planes of the Face).

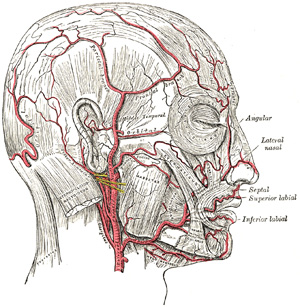

The blood supply to the TPFF is provided by the superficial temporal artery (STA), a terminal branch of the external carotid artery, and courses within the temporoparietal fascia (see Image. Arteries of the Scalp and Face). The STA originates within the parotid gland, and after giving off the transverse facial artery at or just below the level of the zygomatic arch, it typically bifurcates into frontal (anterior) and parietal (posterior) branches, roughly 3 to 5 cm above the level of the zygomatic arch; however, innumerable anatomic variations have been described.[11][12][13] The STA also gives rise to the middle temporal artery, which supplies the temporalis muscle with the deep temporal arteries from the internal maxillary artery. If desired, the surgeon may concomitantly harvest the deep temporal fascia and/or temporalis muscle during the TPFF harvest, with these latter tissues separate from but connected to the main TPFF pedicle via the middle temporal artery.[6]

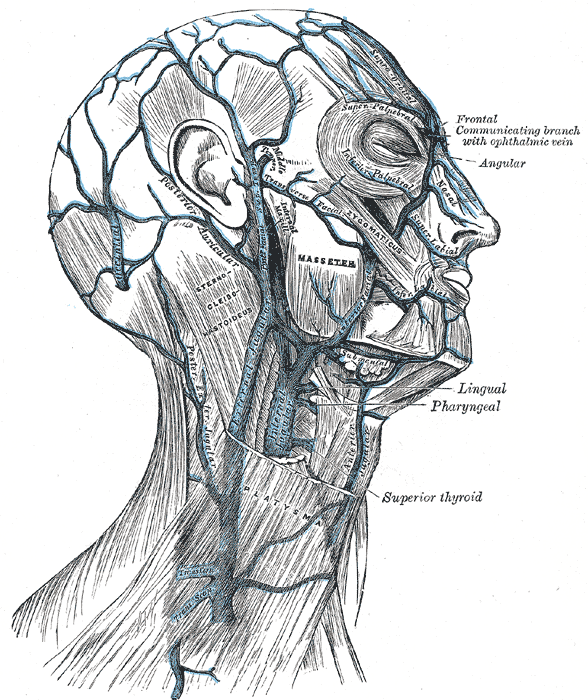

The terminal branches of the STA ultimately arborize with vessels supplying the pericranium. The venous drainage of the TPFF runs through the superficial temporal vein, which parallels the course of the STA, coursing just posterior to it (see Image. Superficial Vessels and Nerves of the Temporal Region). The superficial temporal vein is a tributary of the retromandibular vein (see Image. Veins of the Neck, Head, and Face). When necessary, the STA and vein can be dissected inferiorly to the zygomatic arch, down into the parotid gland, thereby providing at least 3 cm of pedicle length below a large TPFF and increasing the vessel caliber to ~2 mm. The distal branches of the STA have diameters of ~1.5 mm, and the whole system is notoriously prone to spasm, which makes it imperative to handle the artery gently during dissection to preserve blood flow to the flap, particularly when microvascular anastomosis is required.[14]

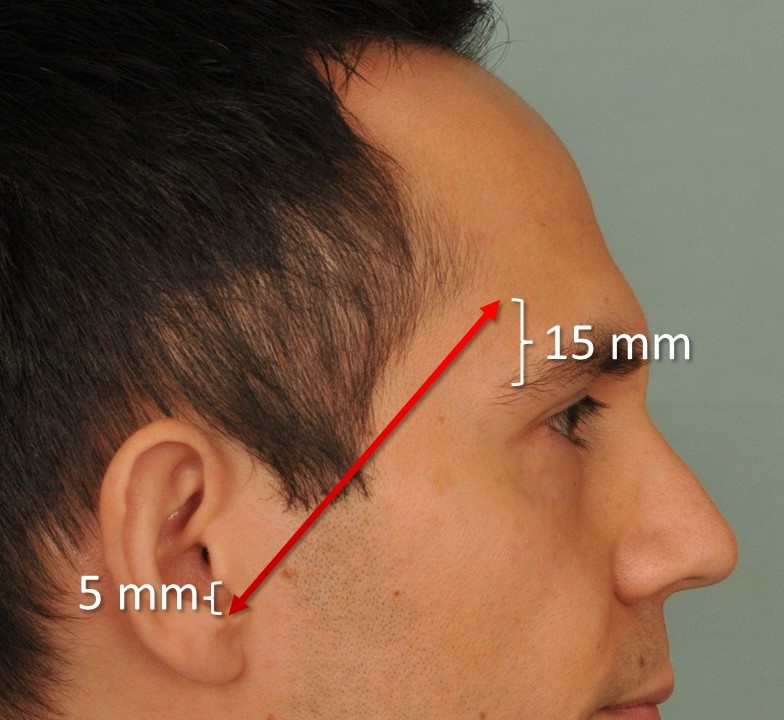

Dissection along the frontal branch of the STA may put the frontal branch of the facial nerve at risk, and care should be taken to preserve the nerve, as injury will result in ipsilateral brow ptosis and forehead paralysis. Various anatomic landmarks can be used to approximate the course of this nerve, the best known of which is the Pitanguy line, drawn from a point 0.5 cm inferior to the tragus to a point 1.5 cm superior to the lateral brow (see Image. Pitanguy Line).[15] This line is an approximation, and multiple frontal nerve branches may be running along this path, spreading out over the central 2 quarters of the zygomatic arch.[16] At least 1 of these branches will usually pass through a point roughly 3 cm superior and 2.5 cm lateral to the lateral canthus.[17] Another reference point is the medial zygomaticotemporal vein (the "sentinel"), which runs 5 to 10 mm inferior to the nerve. However, this is typically only relevant with endoscopic approaches to the temporal region.[16] Ultimately, if the access incisions and dissection of the temporoparietal fascia are performed within the hair-bearing portion of the temporal scalp, and the patient has a normal hairline, the nerve should remain undisturbed.

Indications

TPFF transfer is a foundational technique in head and neck, hand, and lower extremity reconstruction. The TPFF can be harvested as a pedicled flap or a vascularized free flap, with or without other tissue components, depending on the defect needing repair.[18][19][20][21] Without a doubt, however, the thin and pliable nature of the TPFF renders it a great choice for reconstructing a variety of defects involving the skull base, facial soft tissues, nasopharynx, oral cavity, orbit, ear, and scalp.[22][23][24]

Auricular reconstruction for microtia, whether using autologous costal cartilage or porous polyethylene implants, routinely requires TPFF transfer, whether for primary coverage of the implant or the salvage of these reconstructions after trauma or infection.[25][26] TPFF transfer is also commonly used for several other applications in the head and neck, including acting as a barrier between the parotid gland and the skin to reduce the symptoms of Frey syndrome and filling in the soft tissue deficit that remains after temporalis muscle flap transfer or parotidectomy.[27][28][29][30] In hand surgery, the TPFF is well-suited to ensuring reconstructed tendons can glide smoothly within the hand and fingers, making the flap an ideal reconstructive option.[31][32]

Contraindications

There are a few contraindications to consider when performing a TPFF transfer. These include:

- When used as a pedicled flap, the surgeon should first consider the anatomical reach limitations of the proposed TPFF, determined by the combined lengths of the flap and its vascular pedicle. In the case of planned free tissue transfer, a short pedicle and recipient vessels distant from the flap inset site may also contraindicate TPFF transfer.

- Previous radiation therapy may alter the microvasculature of the flap and potentially increase the failure rate.

- Prior trauma, surgery, or manipulation of the superficial temporal vascular system (eg, STA biopsy for giant cell arteritis or ligation during parotidectomy) may have interrupted the flap's vascular supply.

Equipment

Preoperatively

- Surgical marker

- Local anesthesia with epinephrine

- Electric shaver (optional)

- Topical antiseptic

- Based on the clinical scenario, a corneal shield may be considered for eye protection

- Facial nerve monitor (not routinely employed)

Intraoperatively

- Bipolar cautery

- #15 and #10 blade scalpel

- Multiprong retractors or skin hooks

- Forceps (Adson-Brown, DeBakey)

- Dissecting scissors (Metzenbaum, Reynolds tenotomy)

- Dissecting instruments (McCabe, petite-pointe Crile)

- Needle drivers

- Suture scissors

- Titanium surgical clips or 3-0 silk sutures for ligating the superficial temporal vessels distally

- Closed suction drain with bulb (optional)

- 4-0 poliglecaprone suture to close the deep dermal layer of the scalp

- 5-0 gut suture or stapler for the skin surface

- Microscope, microvascular instruments, heparinized saline, papaverine or 4% lidocaine, Weck sponges, microvascular suture, and venous coupler if free tissue transfer is planned

Postoperatively

- Antibiotic ointment

- Dressing supplies (such as a Barton pressure dressing)

Personnel

The personnel needed for a TTPF transfer:

- Surgeon

- Surgical assistant

- Surgical scrub technician

- Operating room nurse (circulator)

- Anesthesiologist and/or nurse anesthetist

Preparation

Patients undergoing a TTPF transfer should be prepared as follows:

- The patient should be risk-stratified and medically optimized for general anesthesia.

- A thorough preoperative head and neck examination, including an assessment of facial nerve function, should be performed.

- Preoperative photography may be considered to document the defect's shape, size, and location.

- The patient should be counseled regarding the procedure's risks, benefits, and alternatives. Pertinent to this procedure, it is crucial to mention flap compromise, alopecia, paresthesias, and facial nerve injury, among the other more common risks associated with surgery (eg, pain, bleeding, infection, scarring, and the need for additional procedures).

- The surgeon should mark the skin incisions in the temporal scalp to ensure maximal preservation of the hairline. The Y- or T-shaped incision is parallel to the STA course.

- Important landmarks are identified, including the STA and trajectory of the frontal branch of the facial nerve.

- General anesthesia is recommended. Long-acting paralytics are usually avoided to permit intraoperative facial nerve monitoring. Similarly, some surgeons will prefer to avoid using local anesthetic agents entirely, instead injecting plain 1:100,000 epinephrine to provide a hemostatic effect without affecting nerve monitoring.

- A single dose of intravenous antibiotics covering skin flora is given preoperatively.

Technique or Treatment

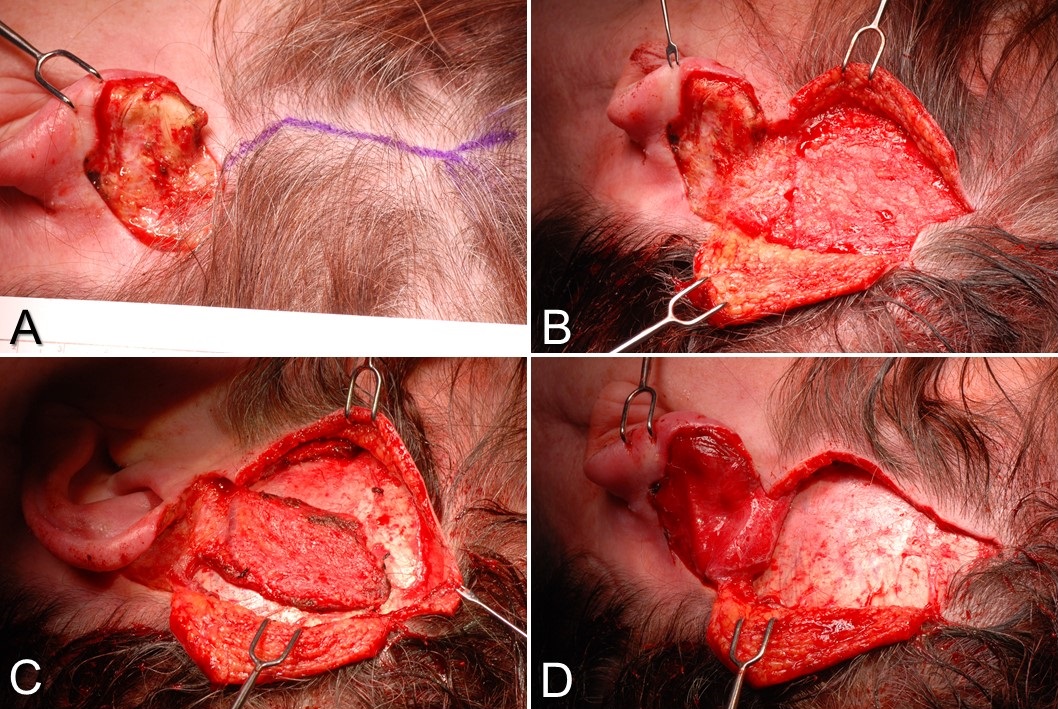

Trimming any hair during this procedure is not strictly necessary. However, it may be helpful to shave the hair 1 to 2 cm beyond the anticipated incision line (see Image. Temporoparietal Fascia Flap).[33] The technique is as follows:

- A Y or T-shaped incision is planned in the preauricular crease and extended several centimeters cranially if no scalp skin is to be harvested. Some surgeons prefer to zigzag the incision's vertical portion to improve postoperatively scar camouflage. If scalp skin will be harvested with the TPFF, the incision is made to include the desired amount of scalp superiorly and to expose the vascular pedicle inferiorly.

- The incision is made through the skin, dermis, and subcutaneous fat. Scalp flaps are then developed anteriorly, posteriorly, and superiorly to the incision to expose the TPFF. The elevation is performed in a subcutaneous plane, just below the level of the hair follicles, which leaves some fat on the TPFF to provide additional thickness. Elevation is performed with a scalpel to avoid thermal injury to the hair follicles and decrease the risk of alopecia. Blades will dull and require replacement frequently.

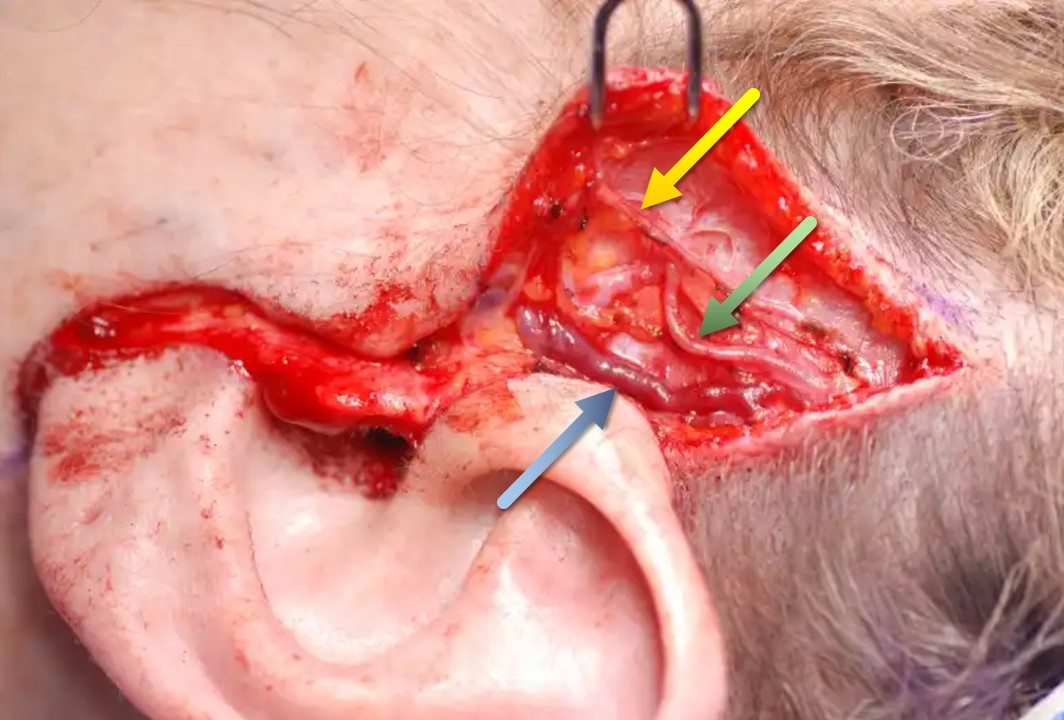

- Care should be taken to avoid injuring the underlying STA, which courses through the substance of the flap itself. Once the required size of the TPFF is exposed, the surgeon can incise the periphery of the temporoparietal fascia sharply, with care taken to preserve the vascular pedicle. At this step, the distal branches of the STA are ligated. The STA should be readily identifiable by its pulse, although it is also visually apparent; no Doppler probe is required.

- The flap can then be elevated off the underlying temporalis muscle fascia (deep temporal fascia), taking care to include the entire thickness of the temporoparietal fascia in the elevation and avoid injury to the STA and vein within the flap itself. Because the temporoparietal fascia is thin and wispy, like loose areolar tissue, it is easy to allow some of its fibers to remain on the deep temporal fascia, but this should be avoided. Elevation of the flap proceeds from superior to inferior, leaving the vascular pedicle intact but ligating branches as the periphery of the flap is incised. The surgeon should be mindful during anterior dissection to avoid injuring the frontal branch of the facial nerve, which lies either deep within or beneath the temporoparietal fascia. Dissection performed underneath the hair-bearing scalp is typically not near enough to the frontal branch of the facial nerve for inadvertent injury to be likely.

- The STA and vein may be dissected proximally to identify the middle temporal artery, which may require entering the parotid gland. Care should be taken to avoid inciting arterial spasm during dissection, as this will temporarily compromise flap perfusion. Should a vasospasm occur, applying papaverine or plain lidocaine or removing arterial adventitia may restore blood flow. The flap may be harvested as a chimeric flap to include the deep temporal fascia and/or temporalis muscle. If desired, the surgeon can extend the dissection beyond the temporal fossa to include pericranium and/or harvest a vascularized calvarium strip (parietal bone's outer cortex).

- The surgeon may rotate or tunnel this flap into the defect, or the vascular bundle may be ligated proximally for free microvascular reconstruction of distant defects.

- An optional closed suction drain may be placed.

- The skin flaps are then reapproximated with deep absorbable sutures, followed by staples or suture closure of the scalp.

- If the TPFF is used to reconstruct a defect that includes skin, but the scalp is not harvested with the flap, a skin graft may be applied on top of the TPFF (eg, during auricular reconstruction).

Complications

Potential complications after TPFF transfer include:

- Alopecia

- Flap necrosis, which may necessitate local wound care or surgical revision

- Frontalis and corrugator supercilii muscle weakness following an injury to the frontal branch of the facial nerve

- Venous congestion, which may be treated with medicinal leeches or revision of the vascular pedicle

- Arterial obstruction, which may resolve with topical nitroglycerin paste or need revision of the vascular pedicle (venous congestion is more common because the pressure in the arterial system is higher and therefore more resistant to blockage)

- Wound breakdown

- Hematoma formation, which may require a return to the operating room for drainage and hemostasis

- Infection

- Unfavorable scarring

- Paresthesia [34]

Most complications can be avoided with meticulous dissection and careful flap elevation that respects the local scalp anatomy. Rates of flap loss (partial or total) are roughly 2.44%.[19] Some degree of alopecia may occur in up to 8% of patients.[31] Injury to the frontal branch of the facial nerve resulting in transient weakness to paralysis may range from 1% to 20%.[35] For more information about managing facial nerve injury, please see Facial Nerve Trauma.

Clinical Significance

TPFF transfer is a workhorse procedure in the armamentarium of the reconstructive surgeon, because it is a low-risk and straightforward option for repairing regional craniofacial and distant soft tissue defects. This procedure has been popular in head and neck reconstruction as a pedicled flap, but it may be harvested as a free flap for extremity reconstruction. Outcomes are very satisfactory in the hands of a knowledgeable surgeon and an experienced care team. Additionally, there is minimal donor site morbidity, with most patients and surgeons not noticing any contour irregularities within the temporal fossa.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Given the technical precision and needed postoperative monitoring, TPFFs in reconstructive surgery require a multidisciplinary approach to optimize patient outcomes. Surgeons must demonstrate advanced microsurgical flap harvest and inset skills, while anesthesiologists ensure intraoperative hemodynamic stability. Nurses are critical in postoperative wound and flap monitoring, particularly in assessing flap perfusion and early detection of complications such as hematoma or venous congestion. Advanced clinicians such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants contribute to continuity of care by reinforcing surgical plans, coordinating follow-up, and addressing early postoperative concerns.

Effective interprofessional communication and structured care coordination are central to patient safety and recovery in TPFF procedures. Pharmacists ensure appropriate analgesic regimens and antibiotic stewardship to reduce infection risk, while rehabilitation specialists support functional and cosmetic recovery. Collaborative care rounds and shared decision-making strategies align the treatment plan with patient goals and expectations. By fostering a cohesive team approach, clinicians enhance surgical outcomes, improve patient-centered care, minimize complications, and strengthen overall team performance in reconstructive surgery.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Recovery following TPFF transfer depends on the complexity of the original problem for which the reconstruction was performed. Local wound care is critical to ensure a healthy and clean healing environment. Suction drains (if placed) can be removed when output has appropriately decreased (eg, less than 30 mL over 24 hours). The patient should avoid rigorous activity for 10 days following surgery to promote wound healing, minimize edema, ecchymosis, and bleeding, and reduce the risk of hematoma formation. After discharge, the patient is typically followed for several weeks to months to ensure a satisfactory outcome.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Fascial Planes of the Face. This illustration depicts the fascial planes of the face, highlighting the continuity of the frontalis muscle, galea aponeurotica, temporoparietal fascia, superficial musculoaponeurotic system, platysma, and the location of the facial nerve.

Contributed by K Humphreys and MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Temporoparietal Fascia Flap. A) This is a postauricular defect from Mohs surgery with too much bare cartilage for a skin graft alone to survive. A Y-shaped incision is planned, paralleling the course of the superficial temporal artery. B) The scalp flaps are elevated in a subdermal plane, exposing the temporoparietal fascia. C) The temporoparietal fascia flap is incised on 3 sides, with the pedicle intact inferiorly. D) The temporoparietal fascia flap is transferred into the defect, after which the scalp will be closed in layers, and a skin graft will be applied to the flap.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Arteries of the Scalp and Face. Shown here are the branches of the internal and external carotid arteries that supply the scalp and face.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Veins of the Neck, Head, and Face. This illustration reveals the veins of the neck, head, and face, along with their branches, including the external and internal jugular veins.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Garfein E, Doscher M, Tepper O, Gill J, Gorlick R, Smith RV. Reconstruction of the pediatric midface following oncologic resection. Journal of reconstructive microsurgery. 2015 Jun:31(5):336-42. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1544181. Epub 2015 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 25803408]

Vinciguerra A, Taboni S, Bettini P, Turri-Zanoni M, Verillaud B, Chatelet F, Castelnuovo P, Nicolai P, Bresson D, Battaglia P, Ferrari M, Herman P. Surgical Anatomy of the Scalp: Technical Hints for Harvesting the Temporoparietal Fascial and Pericranial Flap. Head & neck. 2025 Sep:47(9):2603-2610. doi: 10.1002/hed.28161. Epub 2025 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 40297940]

Holcomb AJ, Deschler DG. Regional Flap Donor Sites in Head and Neck Reconstruction. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2023 Aug:56(4):639-651. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2023.04.008. Epub 2023 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 37246029]

Li D, Xu F, Zhang R, Zhang Q, Xu Z, Li Y, Wang C, Li T. Surgical Reconstruction of Traumatic Partial Ear Defects Based on a Novel Classification of Defect Sizes and Surrounding Skin Conditions. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2016 Aug:138(2):307e-316e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002408. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27465192]

Marks MW, Friedman RJ, Thornton JW, Argenta LC. The temporal island scalp flap for management of facial burn scars. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1988 Aug:82(2):257-61 [PubMed PMID: 3399556]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJose A, Nagori SA, Arya S, Roy ID. Chimeric temporopareital osteofascial and temporalis muscle flap; a novel method for the reconstruction of composite orbito-maxillary defects. Journal of stomatology, oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2019 Jun:120(3):250-254. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2019.02.002. Epub 2019 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 30763779]

Denadai R, Raposo-Amaral CE, Marques FF, Raposo-Amaral CA. Posttraumatic eyebrow reconstruction with hair-bearing temporoparietal fascia flap. Einstein (Sao Paulo, Brazil). 2015 Jan-Mar:13(1):106-9. doi: 10.1590/S1679-45082015RC2834. Epub 2015 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 25993077]

Schreiber M, Dragu A. Free temporal fascia flap to cover soft tissue defects of the foot: a case report. GMS Interdisciplinary plastic and reconstructive surgery DGPW. 2015:4():Doc01. doi: 10.3205/iprs000060. Epub 2015 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 26504730]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOlcott CM, Simon PE, Romo T 3rd, Louie W. Anatomy of the superficial temporal artery in patients with unilateral microtia. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2019 Jan:72(1):114-118. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2018.09.001. Epub 2018 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 30528867]

Mitz V, Peyronie M. The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1976 Jul:58(1):80-8 [PubMed PMID: 935283]

Daskalopoulou D, Matsas A, Chrysikos D, Troupis T. The Superficial Temporal Artery: Anatomy and Clinical Significance in the Era of Facial Surgery and Aesthetic Medicine. Acta medica academica. 2022 Dec:51(3):232-242. doi: 10.5644/ama2006-124.393. Epub 2022 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 36799316]

Rusu MC, Jianu AM, Rădoi PM. Anatomic variations of the superficial temporal artery. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2021 Mar:43(3):445-450. doi: 10.1007/s00276-020-02629-x. Epub 2021 Jan 2 [PubMed PMID: 33386932]

Nguyen HH, Vu D, Ngo LM, Tran HTT. Anatomical variant of the superficial temporal artery in temporoparietal fascia flap for microtia reconstruction. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2024 Apr:91():105-110. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2024.01.029. Epub 2024 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 38412600]

Kim BS, Jung YJ, Chang CH, Choi BY. The anatomy of the superficial temporal artery in adult koreans using 3-dimensional computed tomographic angiogram: clinical research. Journal of cerebrovascular and endovascular neurosurgery. 2013 Sep:15(3):145-51. doi: 10.7461/jcen.2013.15.3.145. Epub 2013 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 24167792]

Pitanguy I, Ramos AS. The frontal branch of the facial nerve: the importance of its variations in face lifting. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1966 Oct:38(4):352-6 [PubMed PMID: 5926990]

Trinei FA, Januszkiewicz J, Nahai F. The sentinel vein: an important reference point for surgery in the temporal region. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1998 Jan:101(1):27-32 [PubMed PMID: 9427913]

Schmidt BL, Pogrel MA, Hakim-Faal Z. The course of the temporal branch of the facial nerve in the periorbital region. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2001 Feb:59(2):178-84 [PubMed PMID: 11213986]

Safavi-Abbasi S, Komune N, Archer JB, Sun H, Theodore N, James J, Little AS, Nakaji P, Sughrue ME, Rhoton AL, Spetzler RF. Surgical anatomy and utility of pedicled vascularized tissue flaps for multilayered repair of skull base defects. Journal of neurosurgery. 2016 Aug:125(2):419-30. doi: 10.3171/2015.5.JNS15529. Epub 2015 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 26613175]

Mokal NJ, Ghalme AN, Kothari DS, Desai M. The use of the temporoparietal fascia flap in various clinical scenarios: A review of 71 cases. Indian journal of plastic surgery : official publication of the Association of Plastic Surgeons of India. 2013 Sep:46(3):493-501. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.121988. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24459337]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJaquet Y, Higgins KM, Enepekides DJ. The temporoparietal fascia flap: a versatile tool in head and neck reconstruction. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2011 Aug:19(4):235-41. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328347f87a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21593668]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMolteni G, Gazzini L, Sacchetto A, Nocini R, Marchioni D. Role of the temporoparietal fascia free flap in salvage total laryngectomy. Head & neck. 2021 May:43(5):1692-1694. doi: 10.1002/hed.26602. Epub 2021 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 33433928]

Collar RM, Zopf D, Brown D, Fung K, Kim J. The versatility of the temporoparietal fascia flap in head and neck reconstruction. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2012 Feb:65(2):141-8. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.05.003. Epub 2011 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 21700520]

Offi M, Mattogno PP, D'Onofrio GF, Serioli S, Valeri F, Della Pepa GM, Arena V, Parrilla C, Chiloiro S, D'Argento F, Gessi M, Pedicelli A, Lauretti L, Paludetti G, Galli J, Olivi A, Rigante M, Doglietto F. Temporoparietal Fascia Flap (TPFF) in Extended Endoscopic Transnasal Skull Base Surgery: Clinical Experience and Systematic Literature Review. Journal of clinical medicine. 2024 Nov 27:13(23):. doi: 10.3390/jcm13237217. Epub 2024 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 39685676]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHoren SR, Hamidian Jahromi A, Konofaos P. Temporoparietal Fascial Free Flap: A Systematic Review. Annals of plastic surgery. 2021 Dec 1:87(6):e189-e200. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002961. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34387574]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTahiri Y, Reinisch J. Porous Polyethylene Ear Reconstruction. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2019 Apr:46(2):223-230. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2018.11.006. Epub 2018 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 30851753]

Reddy NK, Shah ND, Alias BP, Allison S, Chwa ES, Yamada A. Assessing the Current State of Microtia Reconstruction in the United States. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2024 May 9:():. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000010200. Epub 2024 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 38722567]

Andrews J, Kopacz AA, Hohman MH. Ear Microtia. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33085390]

Rubinstein RY, Rosen A, Leeman D. Frey syndrome: treatment with temporoparietal fascia flap interposition. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 1999 Jul:125(7):808-11 [PubMed PMID: 10406323]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMovassaghi K, Lewis M, Shahzad F, May JW Jr. Optimizing the Aesthetic Result of Parotidectomy with a Facelift Incision and Temporoparietal Fascia Flap. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2019 Feb:7(2):e2067. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002067. Epub 2019 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 30881826]

Hamidian Jahromi A, Horen SR, Konofaos P. Implications of Free Temporoparietal Fascial Flap Reconstruction in the Pediatric Population. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2021 Jun 1:32(4):1400-1404. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000007467. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33496524]

Hing DN, Buncke HJ, Alpert BS. Use of the temporoparietal free fascial flap in the upper extremity. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1988 Apr:81(4):534-44 [PubMed PMID: 3347663]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUpton J, Rogers C, Durham-Smith G, Swartz WM. Clinical applications of free temporoparietal flaps in hand reconstruction. The Journal of hand surgery. 1986 Jul:11(4):475-83 [PubMed PMID: 3722753]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePetruzzi G, Zocchi J, Pellini R. Temporoparietal fascia free flap harvesting: A surgical technique video. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2021 Sep:138 Suppl 2():49-51. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2020.11.017. Epub 2021 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 34083173]

Mavropoulos JC, Bordeaux JS. The temporoparietal fascia flap: a versatile tool for the dermatologic surgeon. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2014 Sep:40 Suppl 9():S113-9. doi: 10.1097/dss.0000000000000114. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25158871]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYano H, Fukui M, Yamada K, Nishimura G. Endoscopic harvest of free temporoparietal fascial flap to improve donor-site morbidity. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2001 Apr 1:107(4):1003-9 [PubMed PMID: 11252096]