Introduction

The spleen is one of the most commonly injured intraabdominal organs in trauma, involved in approximately 2% of trauma admissions. Blunt trauma accounts for over 94% of traumatic splenic injury, and the remainder is largely secondary to stabbing and high-velocity weaponry. Injuries can range from small capsular tears to focal vascular injuries such as pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae to high-grade fractures with active arterial bleeding. The vascular nature of the spleen makes it susceptible to arterial bleeding, causing significant hemoperitoneum and hemodynamic compromise and instability, often necessitating splenectomy.[1]

However, the spleen plays a vital role in innate and adaptive immunity, hematopoiesis, and the clearance of cellular debris. Consequently, nonoperative management is now the standard of care for hemodynamically stable patients, including those with high-grade splenic injuries. The primary goal is splenic preservation, and recent advances permit precise localization and control of bleeding vessels. When surgical intervention is necessary, splenorrhaphy is preferred over splenectomy when feasible.[2]

Splenectomy increases susceptibility to infections caused by encapsulated pathogens and parasites that reside within erythrocytes. Overwhelming postsplenectomy sepsis still carries a 50% mortality.[3] Patients are also at elevated risk for early and delayed infections and may have an increased risk for thromboembolic complications. The effective use of diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies is key to improving outcomes and minimizing preventable morbidity and mortality.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

In the United States, most splenic trauma is due to blunt injury, usually from motor vehicle collisions, with additional cases caused by assaults and falls. Penetrating trauma accounts for approximately 5% of all splenic injuries and involves stab and gunshot wounds.[4] In pediatric patients, nonaccidental trauma should always be considered. Indirect mechanisms, such as excessive traction on the splenocolic ligament or a tear during colonoscopy, can also result in injury. Preexisting splenomegaly weakens the capsule and increases susceptibility, particularly in the less protected inferior portion of the spleen.[5][6]

Epidemiology

The spleen is the most frequently injured solid organ in both blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma. Blunt trauma accounts for a significant proportion of pediatric abdominal trauma. At major trauma centers, embolization is increasingly utilized, especially in the management of higher-grade splenic injuries. However, outcomes differ by injury mechanism. Patients with penetrating trauma have higher splenectomy rates following embolization than those with blunt trauma. Around one-third of individuals with penetrating trauma who underwent embolization later required splenectomy, compared to about 5% of blunt trauma patients.[4][7]

Pathophysiology

The average adult spleen weighs approximately 250 g and measures about 13 cm in length. The spleen involutes with age and is typically not palpable in adults. Injury can result in hemorrhage from parenchymal disruption or vascular injury. Splenic trauma may involve intraparenchymal or subcapsular hematoma with or without capsular disruption. Splenectomy affects red cell clearance, humoral immunity, and predisposes to infection.[7]

Splenic injuries are graded I through V by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST):

- Grade I: Subcapsular hematoma <10%, capsular laceration <1 cm

- Grade II: Hematoma 10% to 50%, laceration 1 to 3 cm

- Grade III: Hematoma >50% or expanding, laceration >3 cm or involving a trabecular vessel

- Grade IV: Laceration involving segmental/hilar vessel, >25% devascularization

- Grade V: Shattered spleen or complete devascularization [4][8][9]

History and Physical

A person with suspected splenic trauma will typically report recent, significant trauma, such as a motor vehicle collision, high-impact injury, or assault with a weapon. These cases may present with life-threatening hemodynamic compromise due to penetrating or blunt injury. However, the history may be more subtle, including a fall or abdominal discomfort following impact sports. Any trauma to the left upper quadrant should raise suspicion for splenic injury.

Per institutional protocol and Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines, a complete trauma evaluation should be performed for all high-impact mechanisms.[10] Even delayed presentations following injury warrant a full trauma assessment. Clinicians should obtain a thorough medical history, including recent infections and anticoagulant use.[8]

Splenic injury can present with a broad range of physical examination findings, and 10% to 20% of patients may lack obvious signs. Common findings include abdominal tenderness and peritoneal signs. The Kehr sign—pain in the left shoulder worsened by inspiration—may be reported, and some patients may complain of left-sided pleuritic pain. Physical examination may reveal abdominal wall contusions, hematomas, seatbelt marks, or lacerations. Lower left rib tenderness, crepitus, or deformity increases suspicion for splenic injury.

In adults, up to 20% of patients with lower left rib fractures have associated splenic trauma. In children, compliant chest walls may hide significant underlying injury without rib fractures. A normal exam does not exclude splenic injury if the mechanism or symptoms are concerning. Distracting injuries or altered mental status may delay diagnosis.[11][12] The most predictive findings of intra-abdominal injury following blunt trauma include the seatbelt sign, rebound tenderness, hypotension, abdominal distension, guarding, and associated femur fracture—but their absence does not rule out injury. Once splenic injury is confirmed, evaluation for additional injuries is essential.[13][14]

Evaluation

Imaging is essential in the evaluation of splenic injury. The Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST) is a rapid diagnostic tool used to detect free intraperitoneal fluid in blunt abdominal trauma and is particularly useful in unstable individuals. Splenic laceration may be indicated by an anechoic band or black rim surrounding the spleen. If the splenic capsule remains intact, intraperitoneal bleeding may not be present. Up to 25% of splenic injuries do not demonstrate extracapsular hemorrhage.[8] Prompt surgical evaluation is warranted when free fluid is seen on FAST in an unstable individual.[5]

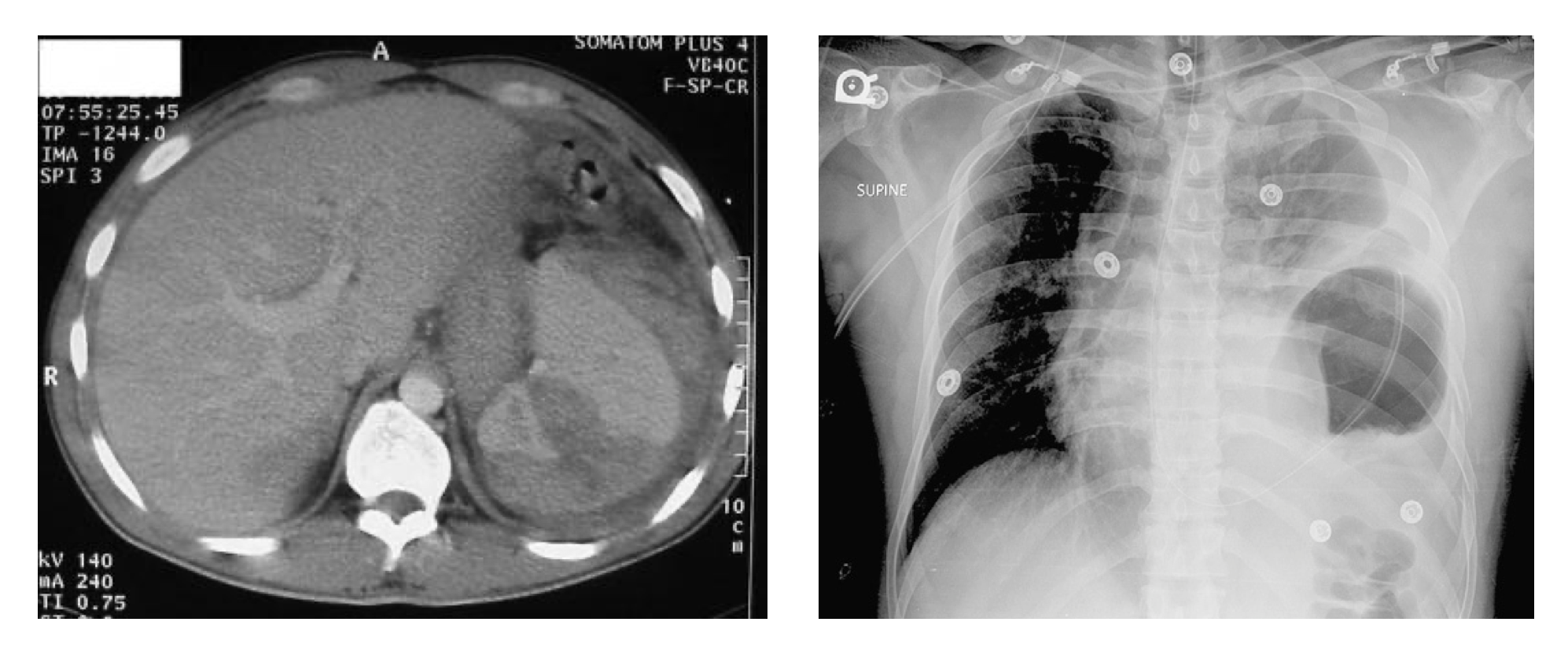

Computed tomography (CT) provides a rapid and accurate assessment in hemodynamically stable individuals, revealing disruptions in splenic parenchyma, hematomas, and hemoperitoneum. Contrast-enhanced CT may demonstrate hypodense areas, contrast blush, or extravasation. Without intravenous contrast, subtle bleeding may not be detected, even with high-resolution imaging. Plain chest x-rays (CXRs) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are of limited utility in the acute trauma setting. Repeat CT is not routinely indicated unless there is clinical deterioration (see Image. Suspected Splenic Injury, Comparative Analysis of Computed Tomography (CT) and Chest X-ray (CXR) Imaging Findings).[5][15][16]

Vital sign monitoring is essential. A hematocrit below 30% may suggest intra-abdominal injury following blunt trauma, but a normal hematocrit does not exclude bleeding. The white blood cell (WBC) count is nonspecific; elevations may occur due to a stress response or injury. WBC counts between 12,000 and 20,000/μL with a left shift are common and may also occur in solid organ or hollow viscus injury.[15]

Treatment / Management

Splenic preservation is the primary treatment goal in hemodynamically stable patients with splenic injury. Nonoperative management includes resuscitation with crystalloids and, when indicated, transfusion of blood products, along with continuous monitoring and serial laboratory assessments, including hematocrit and coagulation studies. Hemodynamically stable persons with higher-grade injuries are typically scheduled for follow-up imaging, with a low threshold for intervention in cases of active bleeding. Management options may include embolization, surgery, or a combination approach. Sudden hemodynamic deterioration or failure to stabilize with resuscitation necessitates prompt invasive intervention.[17][18](B3)

The protocol for managing moderate to severe splenic injuries, including those with grade III injuries, subcapsular hematomas of more than 50% of the surface area, an intraparenchymal hematoma larger than 5 cm, or a parenchymal laceration deeper than 3 cm, varies by institution. Management strategies range from empiric endovascular intervention to scheduled follow-up imaging at a defined interval after injury. These injuries are associated with a higher rate of nonoperative management failure.[19] Approximately 8% of patients admitted for nonoperative management undergo splenic artery embolization. Indications for arterial embolization include arterial contrast extravasation seen on imaging, pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula, higher-grade injuries, and hemoperitoneum.[20] (A1)

Injuries considered for embolization are generally grade III or higher, with evidence of ongoing bleeding. According to the 2022 World Society of Emergency Surgery, splenic artery embolization is recommended as the primary intervention in hemodynamically stable individuals presenting with arterial blush on CT.[5][19][21] Splenic artery embolization can preserve partial or full splenic function. Some institutions consider preservation of at least 50% of the splenic mass sufficient to maintain immune function. This functional threshold is based on the spleen's role in filtering blood, mounting immune responses, and clearing encapsulated organisms.(B3)

There are 2 main anatomical approaches to embolization: proximal and distal. Proximal embolization is performed at the level of the dorsal and great pancreatic arteries, while distal embolization occurs beyond the origin of the caudal pancreatic artery. Proximal embolization is typically used for high-grade injuries to reduce perfusion pressure throughout the spleen. In contrast, distal embolization targets more focal bleeding or specific vascular anomalies.

Proximal embolization is associated with less contrast and shorter procedure time. Distal embolization, however, requires microcatheters, more contrast, and takes longer to complete. There is ongoing debate regarding the comparative risks and benefits of the optimal technique, equipment, and various methods. Topics of discussion include rebleeding rates, infection, infarction, and the efficacy of coils and plugs versus foam embolic agents.[22][23][24] Vascular access for embolization is obtained through either the radial or femoral artery. Radial artery access may result in quicker splenic artery cannulation. Once access is established, the celiac artery is cannulated, and an angiogram is obtained to visualize the blood supply. The goal is to preserve perfusion to the pancreas and allow collaterals to reach the spleen.(A1)

Embolization is achieved via coils, plugs, or gelatin sponges. Coils are detachable or pushable; newer coil versions may come with attached nylon or hydrogel to enhance thrombus formation. Gelatin sponges (eg, Gelfoam) are made from porcine skin, gelatin, and water. These sponges are highly absorptive and serve as a temporary embolic agent, typically reabsorbing within several weeks.[19] The benefits of gelatin sponges used in conjunction with distal embolization are potentially greater splenic salvage, preservation of proximal access points, and reduced cost.[25][26](B2)

Splenic salvage with endovascular treatment was reported to be successful in 90% of cases in a Turkish study conducted at a level I trauma center. The study used either distal embolization with foam or a proximal approach with coils. Researchers found neither method alone increased the risk of splenic infarction; however, combining both techniques was associated with a higher incidence of splenic infarction and abscess formation.[20][26] The study included 450 adults with blunt splenic trauma; patients with hemodynamic instability proceeded to splenectomy, while those who were stable underwent CT. Patients with moderate-to-high-grade injuries were referred for embolization. Stable individuals were monitored and referred for repeat CT imaging if they developed any signs of hemodynamic instability.(A1)

The embolization procedure involved accessing the femoral artery and performing celiac artery angiography. Proximal embolization was defined as targeting the segment distal to the dorsal pancreatic artery but proximal to the splenic hilum. In contrast, distal embolization was performed within splenic branches distal to collateral arteries. The procedure was considered complete once extravasation was no longer visible, and success was measured by splenic salvage at 30-day follow-up.[19](B3)

Operative intervention with splenectomy is life-saving for patients with high-grade splenic injuries with uncontrolled bleeding. Hybrid operating rooms or fluoroscopy suites may allow for endoscopic attempts at splenic salvage in conjunction with surgical decision-making. When feasible, surgical splenic preservation may also be attempted. Most patients who do not respond to resuscitation require operative exploration. General indications for splenectomy include hemodynamic instability, peritonitis, pseudoaneurysm, and associated intra-abdominal injuries requiring surgical exploration. Delayed splenic rupture is a recognized complication that may occur up to 10 days following an injury. The rate of late bleeding, estimated to be as high as 10.6%, varies depending on the grade rating of the splenic injury.

Treatment algorithms for splenic injury vary by institution. In general, those who are hemodynamically unstable are taken directly to the operating room. Patients who are responsive to resuscitation but exhibit active extravasation may be treated with interventional radiology. Those with lower-grade injuries are admitted for resuscitation and monitoring, and may undergo CT-angiogram before discharge.

During observation, transfusion of more than 50% of the estimated circulating blood volume, equivalent to approximately 40 mL/kg packed red blood cells, may indicate the need for surgical intervention. Pediatric patients with splenic injuries are optimally treated in pediatric centers. Those cared for in adult trauma centers have a higher rate of splenectomy.[9]

Post a splenectomy, patients should receive vaccinations before discharge or within 2 weeks to lower the risk of sepsis. Common organisms include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenzae type b. The 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and others, such as PCV20 (Prevnar 20) and PedvaxHIB, are recommended. Despite widespread pediatric immunization, postsplenectomy recommendations remain unchanged.[27][28](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for splenic injury include hepatic laceration, renal trauma, retroperitoneal bleeding, diaphragmatic rupture, and pancreatic injury. The FAST exam can help quickly identify potential sites of injury.[29] The presence of free intraperitoneal fluid in those with trauma should prompt consideration of splenic injury, even when physical findings are nonspecific.[30][31][32][33] A negative FAST exam does not exclude injury. CT imaging with intravenous contrast remains the most accurate modality for characterizing splenic trauma.[29][30]

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Nonoperative management of splenic trauma has advanced significantly with improvements in technology and clinical capabilities. With splenic artery embolization more widely available, even higher-grade splenic injuries are increasingly managed with organ preservation rather than removal.[34][35] Nonoperative management is not always feasible. One case involved a patient with a grade IV splenic laceration, pseudoaneurysm, and hemoperitoneum in the context of active polysubstance use, including amphetamines, benzodiazepines, and fentanyl. An initial trial of nonoperative management was complicated by a reluctant patient and anatomical limitations that rendered embolization unfeasible due to a tortuous splenic artery. The situation was further complicated by a fall from bed and progressive hemoperitoneum, ultimately necessitating splenectomy.[36]

Retrospective analysis of 8195 adults with blunt splenic trauma in Taiwan over 15 years compared outcomes among those treated with splenic artery embolization or observation versus those who underwent splenectomy. The study's results found no difference in outcomes between cases managed nonoperatively; however, those who underwent splenectomy had significantly higher rates of all-cause mortality, infection, malignancy, and thromboembolism.[7] Further, the SPEED (SPlEnic Embolisation Decisions) study is investigating treatment protocols for splenic trauma across trauma centers in England to assess how institutional logistics influence the utilization and outcomes of splenic artery embolization.[37] Preliminary findings aim to guide the standardization of care and improve access to embolization for appropriate patients.

Staging

Staging of splenic injury was previously introduced under Pathophysiology and is further summarized here for clarity. The World Society of Emergency Surgery categorizes splenic injuries as minor, moderate, or severe based on clinical presentation, with severe injuries linked to hemodynamic instability. The AAST grading system remains the standard for injury classification and integrates imaging, surgical, and pathological findings. Higher-grade injuries are associated with an increased risk of nonoperative failure and a greater likelihood of requiring intervention.[8][38]

Prognosis

Overall, patients with low-grade splenic injury treated nonoperatively typically experience favorable outcomes. In cases of high-grade splenic trauma, the time to laparotomy or endovascular intervention significantly influences prognosis. Splenic salvage remains the preferred approach due to its role in maintaining immune function; it is more frequently achieved at major trauma centers with access to interventional radiology and surgical expertise.[39] In contrast, patients in remote settings may achieve better outcomes with immediate surgery at the nearest functional operating room, as transport delays can worsen blood loss and clinical deterioration.

Some study results suggest that delayed laparotomy may offer no more benefit than continued nonoperative management, though further investigation is needed.[32] Patients who undergo splenectomy remain at increased risk for overwhelming postsplenectomy sepsis, although this has been mitigated in part by vaccination against S pneumoniae, H influenzae, and N meningitidis. However, variability in vaccination adherence continues to influence infectious outcomes.[40]

Patients with pseudoaneurysm, active extravasation on CT, or grade III to V injuries are at greater risk of failure of nonoperative care.[19] Those who undergo splenectomy also have a higher incidence of early infection and may have an increased incidence of malignancies involving the gastrointestinal tract, hematologic system, and head and neck. Markers of splenic dysfunction, such as Howell-Jolly bodies, are typically absent after embolization, suggesting that volume loss does not necessarily equate to impaired immune function.[19]

Complications

Complications following splenic injuries include delayed splenic rupture, which may occur up to 10 days post-injury and is often associated with subtle low-grade injuries that may not have been detected on initial imaging studies. Other complications include readmission due to bleeding (estimated at 1.4%), splenic artery pseudoaneurysm, splenic abscess, and pancreatitis. Complications specific to embolization include splenic infarction, defined as devascularization of more than 25% of the spleen, which may occur in up to 20% of patients and is more common following distal embolization.

Other embolization-related risks include arterial dissection, pulmonary effusion, coil migration, gelatin-associated complications, rebleeding, and abscess formation.[19] The failure rate of nonoperative management ranges from 3.4% to 27%, depending on the injury grade, and is noted to decrease when pseudoaneurysms are treated with embolization.[19] The effects of splenectomy include a poor response to particulate antigens, decreased phagocytic capacity, deficiency of serum immunoglobulin M, and decreased properdin levels—factors that collectively increase the risk of long-term infection.[41]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients undergoing splenectomy should receive vaccinations against pneumococcus, H influenzae type b, and meningococcus before discharge or by day 14 postoperatively. Additional vaccines, such as influenza, tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap), and varicella, may also be indicated. Pediatric patients may require penicillin prophylaxis (250 mg daily) for 2 years or more. Lifelong antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for high-risk populations; pre-procedural antibiotics should be administered before dental work or invasive procedures. Providing patients with clear discharge instructions regarding infection risk and follow-up care is essential.[42]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Injury prevention is a key focus of trauma care leadership. In developed nations, some experts suggest that improvements in infrastructure and public education could help prevent many trauma-related deaths and injuries.[43][44][45] Clear guidelines and preventive measures benefit patients with splenic injury. Delayed splenic bleeding or rupture can occur even after minor trauma, so patients should be counseled on when to seek reevaluation, particularly if they experience left-sided abdominal pain. Splenectomy increases lifelong infection risk, especially from encapsulated organisms such as S pneumoniae, N meningitidis, and H influenzae type b. Less commonly, gram-negative organisms, including Escherichia coli, Salmonella species, and Pseudomonas species, may also be involved.

To prevent postsplenectomy infection, it is essential to administer prophylactic antibiotics, ensure immunization against encapsulated bacteria, and educate patients on recognizing early signs of infection. Patients should also be informed about travel-related risks such as malaria and babesiosis, and zoonotic infections like Capnocytophaga canimorsus from dog bites. Laminated medical alert cards and identification bracelets are recommended for individuals with asplenia.[11]

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about splenic trauma include the following:

- The spleen is one of the most commonly injured organs in blunt abdominal trauma.

- The standard of care for hemodynamically stable individuals with blunt splenic injury is nonoperative management. This includes clinical and radiological observation, with or without angioembolization.

- Immediate laparotomy is indicated for patients with hemodynamic instability or diffuse peritonitis following blunt abdominal trauma.

- A negative FAST exam does not exclude significant injury. Lower left-sided rib fractures are particularly associated with splenic trauma.[46]

- Intravenous contrast-enhanced CT scans are the gold standard for diagnosing splenic injuries and assessing their severity.

- AAST Organ Injury Scale is commonly used to grade splenic injuries.

- Potential complications of splenic trauma include delayed rupture, pseudoaneurysm formation, and overwhelming postsplenectomy infections due to the loss of the spleen's immunological function.

- To mitigate the risk of severe infections, patients who undergo splenectomy should receive vaccinations against encapsulated bacteria, such as S pneumoniae, H influenzae type b, and N meningitidis.

- Smaller hospitals have higher splenectomy rates due to limited monitoring and interventional radiology. Transferring stable individuals with low- to moderate-grade injuries to tertiary centers increases splenic salvage, while unstable high-grade injuries often require immediate splenectomy regardless of setting.

- A retrospective 7-year study of blunt splenic injuries in children younger than 16 found that those treated at adult hospitals were 3 times more likely to undergo splenectomy or embolization compared to similar injuries managed at pediatric hospitals.[47]

- As nonoperative management increases, follow-up imaging protocols vary. A review found 4.5% had vascular injuries and 60% required intervention. Routine imaging is advised for high-grade injuries or contrast blush, while others recommend imaging only with clinical changes like pain, tachycardia, or hematocrit drop.[48][49]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Collaboration between surgery and interventional radiology has expanded the use of splenic salvage in patients who might previously have required laparotomy and splenectomy. Interprofessional evaluation helps determine which patients are best treated with surgery, embolization, or observation. Emergency department staff, critical care teams, nurses, and operating room personnel are essential to this collaborative approach.[8][50][51][52]

A case illustrating the value of interdisciplinary care involved a patient with high-grade splenic trauma and active polysubstance use. Initially reluctant to receive treatment, the patient ultimately underwent emergent splenectomy for ongoing hemorrhage, left against medical advice postoperatively, and later returned for vaccinations. Coordinated input from emergency medicine, trauma surgery, nursing, addiction medicine, case management, and social work was essential to the patient's care.[36]

Management of splenic trauma relies on an interprofessional team that includes physicians, advanced practice practitioners, nurses, radiologists, intensivists, and laboratory staff. Clinicians must remain vigilant for physiological and immunologic changes post-injury. Pharmacists play a key role in verifying vaccine schedules and coordinating follow-up immunizations after splenectomy. Primary care clinicians, including pediatricians, oversee long-term vaccination plans and infection prevention strategies in the outpatient setting.[42]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Suspected Splenic Injury, Comparative Analysis of Computed Tomography (CT) and Chest X-ray (CXR) Imaging Findings. The CT scan (left image) depicts a severe splenic injury (grades IV-V), whereas the accompanying CXR scan (right image) suggests a rupture of the left hemidiaphragm.

Contributed by M Pellegrini, PharmD

References

Koskinen SK, Alagic Z, Enocson A, Kistner A. The prevalence of early contained vascular injury of spleen. Scientific reports. 2024 Apr 4:14(1):7917. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-58626-2. Epub 2024 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 38575738]

Jakob DA, Müller M, Kolitsas A, Exadaktylos AK, Demetriades D. Surgical Repair vs Splenectomy in Patients With Severe Traumatic Spleen Injuries. JAMA network open. 2024 Aug 1:7(8):e2425300. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.25300. Epub 2024 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 39093564]

Manohar B, Shergill J, Jabbal HS, Goyal D, Singh MP. Splenic Trauma in the Immunocompromised: Unveiling Complexities and Dilemmas. Cureus. 2024 May:16(5):e60718. doi: 10.7759/cureus.60718. Epub 2024 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 38903326]

Jenkins P, Sorrell L, Zhong J, Harding J, Modi S, Smith JE, Allgar V, Roobottom C. Management of penetrating splenic trauma; is it different to the management of blunt trauma? Injury. 2025 May:56(5):112084. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2024.112084. Epub 2024 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 39701904]

Werner NL, Zarzaur BL. Contemporary management of adult splenic injuries: What you need to know. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2025 Jun 1:98(6):840-849. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004570. Epub 2025 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 40128168]

Zhang J, Zhu G, Liu L, Xu S, Jia C. Delayed Traumatic Splenic Rupture as a Life-threatening Clinical Manifestation Treatable with Splenectomy: A Study of Twelve Cases and Literature Review. Annali italiani di chirurgia. 2025:96(3):296-308. doi: 10.62713/aic.3767. Epub [PubMed PMID: 40090850]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHuang JF, Kuo LW, Hsu CP, Cheng CT, Chan SY, Li PH, Chen SA, Wang CC, Tee YS, Ou Yang CH, Liao CH, Fu CY. Long-term follow-up of infection, malignancy, thromboembolism, and all-cause mortality risks after splenic artery embolization for blunt splenic injury: comparison with splenectomy and conservative management. BJS open. 2025 Mar 4:9(2):. doi: 10.1093/bjsopen/zraf037. Epub [PubMed PMID: 40231931]

Coccolini F, Montori G, Catena F, Kluger Y, Biffl W, Moore EE, Reva V, Bing C, Bala M, Fugazzola P, Bahouth H, Marzi I, Velmahos G, Ivatury R, Soreide K, Horer T, Ten Broek R, Pereira BM, Fraga GP, Inaba K, Kashuk J, Parry N, Masiakos PT, Mylonas KS, Kirkpatrick A, Abu-Zidan F, Gomes CA, Benatti SV, Naidoo N, Salvetti F, Maccatrozzo S, Agnoletti V, Gamberini E, Solaini L, Costanzo A, Celotti A, Tomasoni M, Khokha V, Arvieux C, Napolitano L, Handolin L, Pisano M, Magnone S, Spain DA, de Moya M, Davis KA, De Angelis N, Leppaniemi A, Ferrada P, Latifi R, Navarro DC, Otomo Y, Coimbra R, Maier RV, Moore F, Rizoli S, Sakakushev B, Galante JM, Chiara O, Cimbanassi S, Mefire AC, Weber D, Ceresoli M, Peitzman AB, Wehlie L, Sartelli M, Di Saverio S, Ansaloni L. Splenic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2017:12():40. doi: 10.1186/s13017-017-0151-4. Epub 2017 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 28828034]

Koide Y, Okada T, Yamaguchi M, Sugimoto K, Murakami T. The Management of Splenic Injuries. Interventional radiology (Higashimatsuyama-shi (Japan). 2024 Nov 1:9(3):149-155. doi: 10.22575/interventionalradiology.2022-0003. Epub 2023 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 39559801]

Bell RM, Krantz BE, Weigelt JA. ATLS: a foundation for trauma training. Annals of emergency medicine. 1999 Aug:34(2):233-7 [PubMed PMID: 10424930]

Wiik Larsen J, Thorsen K, Søreide K. Splenic injury from blunt trauma. The British journal of surgery. 2023 Aug 11:110(9):1035-1038. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znad060. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36916679]

Basukala S, Tamang A, Bhusal U, Sharma S, Karki B. Delayed splenic rupture following trivial trauma: A case report and review of literature. International journal of surgery case reports. 2021 Nov:88():106481. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.106481. Epub 2021 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 34634610]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWilliamson J. Splenic injury: diagnosis and management. British journal of hospital medicine (London, England : 2005). 2015 Apr:76(4):204-6, 227--9. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2015.76.4.204. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25853350]

El-Matbouly M, Jabbour G, El-Menyar A, Peralta R, Abdelrahman H, Zarour A, Al-Hassani A, Al-Thani H. Blunt splenic trauma: Assessment, management and outcomes. The surgeon : journal of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons of Edinburgh and Ireland. 2016 Feb:14(1):52-8. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2015.08.001. Epub 2015 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 26330367]

Güsgen C, Breuing J, Prediger B, Bieler D, Schwab R. Surgical management of injuries to the abdomen in patients with multiple and/or severe trauma- a systematic review and clinical practice guideline update. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2025 Apr 16:51(1):177. doi: 10.1007/s00068-025-02841-7. Epub 2025 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 40237811]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChatzopoulou D, Alfa-Wali M, Hewertson E, Baxter M, Cole E, Elberm H. Injury patterns and patient outcomes of abdominal trauma in the elderly population: a 5-year experience of a Major Trauma Centre. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2025 Mar 12:51(1):130. doi: 10.1007/s00068-025-02807-9. Epub 2025 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 40074879]

Schaid TR Jr, Moore EE, Williams R, Sauaia A, Bernhardt IM, Pieracci FM, Yeh DD. Splenectomy versus angioembolization for severe splenic injuries in a national trauma registry: To save, or not to save, the spleen, that is the question. Surgery. 2025 Apr:180():109058. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2024.109058. Epub 2025 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 39756336]

Reis MI, Gomes A, Patrício B, Nunes V. Standard of care for blunt spleen trauma: embracing non-operative management. BMJ case reports. 2025 Jan 28:18(1):. pii: e263908. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2024-263908. Epub 2025 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 39875153]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRoh S. Splenic artery embolization for trauma: a narrative review. Journal of trauma and injury. 2024 Dec:37(4):252-261. doi: 10.20408/jti.2024.0056. Epub 2024 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 39736501]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWagner HJ, Goossen K, Hilbert-Carius P, Braunschweig R, Kildal D, Hinck D, Albrecht T, Könsgen N. Endovascular management of haemorrhage and vascular lesions in patients with multiple and/or severe injuries: a systematic review and clinical practice guideline update. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2025 Jan 16:51(1):22. doi: 10.1007/s00068-024-02719-0. Epub 2025 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 39820621]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTsurkan VA, Shabunin AV, Grekov DN, Bedin VV, Arablinskiy AV, Yakimov LA, Shikov DV, Ageeva AA. [Endovascular technologies in the treatment of patients with blunt abdominal trauma]. Khirurgiia. 2024:(8):108-117. doi: 10.17116/hirurgia2024081108. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39140952]

Cusumano LR, Duckwiler GR, Roberts DG, McWilliams JP. Treatment of Recurrent Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations: Comparison of Proximal Versus Distal Embolization Technique. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2020 Jan:43(1):29-36. doi: 10.1007/s00270-019-02328-0. Epub 2019 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 31471718]

Matsumoto T, Yoshimatsu R, Shibata J, Osaki M, Maeda H, Miyatake K, Noda Y, Yamanishi T, Baba Y, Hirao T, Yamagami T. Transcatheter arterial embolization of nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding with n-butyl cyanoacrylate or coils: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific reports. 2024 Nov 9:14(1):27377. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-79133-4. Epub 2024 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 39521898]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYonemitsu T, Kawai N, Sato M, Tanihata H, Takasaka I, Nakai M, Minamiguchi H, Sahara S, Iwasaki Y, Shima Y, Shinozaki M, Naka T, Shinozaki M. Evaluation of transcatheter arterial embolization with gelatin sponge particles, microcoils, and n-butyl cyanoacrylate for acute arterial bleeding in a coagulopathic condition. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2009 Sep:20(9):1176-87. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.06.005. Epub 2009 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 19643634]

Gill K, Aleman S, Fairchild AH, Üstünsöz B, Laney D, Smith AA, Ferral H. Splenic artery embolization in the treatment of blunt splenic injury: single level 1 trauma center experience. Diagnostic and interventional radiology (Ankara, Turkey). 2024 Jul 11:():. doi: 10.4274/dir.2024.242789. Epub 2024 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 38988193]

Jawa RS, Gupta A, Vosswinkel J, Shapiro M, Hou W. Are interventional radiology techniques ideal for nonpenetrating splenic injury management: Robust statistical analysis of the Trauma Quality Program database. PloS one. 2024:19(12):e0315544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0315544. Epub 2024 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 39739692]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOrangzeb S, Watle SV, Caugant DA. Adherence to vaccination guidelines of patients with complete splenectomy in Norway, 2008-2020. Vaccine. 2023 Jul 12:41(31):4579-4585. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.06.034. Epub 2023 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 37336662]

Bianchi FP, Stefanizzi P, Spinelli G, Mascipinto S, Tafuri S. Immunization coverage among asplenic patients and strategies to increase vaccination compliance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert review of vaccines. 2021 Mar:20(3):297-308. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2021.1886085. Epub 2021 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 33538617]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFeliciano DV. Abdominal Trauma Revisited. The American surgeon. 2017 Nov 1:83(11):1193-1202 [PubMed PMID: 29183519]

Leppäniemi A. Nonoperative management of solid abdominal organ injuries: From past to present. Scandinavian journal of surgery : SJS : official organ for the Finnish Surgical Society and the Scandinavian Surgical Society. 2019 Jun:108(2):95-100. doi: 10.1177/1457496919833220. Epub 2019 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 30832550]

Maron S, Baker MS. Splenic rupture due to extraperitoneal gunshot wound: use of peritoneal lavage in the low-tech environment. Military medicine. 1994 Mar:159(3):249-50 [PubMed PMID: 8041476]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMitchell TA, Wallum TE, Becker TE, Aden JK, Bailey JA, Blackbourne LH, White CE. Nonoperative management of splenic injury in combat: 2002-2012. Military medicine. 2015 Mar:180(3 Suppl):29-32. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00411. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25747627]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcGaha P 2nd, Motghare P, Sarwar Z, Garcia NM, Lawson KA, Bhatia A, Langlais CS, Linnaus ME, Maxson RT, Eubanks JW 3rd, Alder AC, Tuggle D, Ponsky TA, Leys CW, Ostlie DJ, St Peter SD, Notrica DM, Letton RW. Negative Focused Abdominal Sonography for Trauma examination predicts successful nonoperative management in pediatric solid organ injury: A prospective Arizona-Texas-Oklahoma-Memphis-Arkansas + Consortium study. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2019 Jan:86(1):86-91. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002074. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30575684]

Abbas Q, Jamil MT, Haque A, Sayani R. Use of Interventional Radiology in Critically Injured Children Admitted in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of a Developing Country. Cureus. 2019 Jan 19:11(1):e3922. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3922. Epub 2019 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 30931193]

Gates RL, Price M, Cameron DB, Somme S, Ricca R, Oyetunji TA, Guner YS, Gosain A, Baird R, Lal DR, Jancelewicz T, Shelton J, Diefenbach KA, Grabowski J, Kawaguchi A, Dasgupta R, Downard C, Goldin A, Petty JK, Stylianos S, Williams R. Non-operative management of solid organ injuries in children: An American Pediatric Surgical Association Outcomes and Evidence Based Practice Committee systematic review. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2019 Aug:54(8):1519-1526. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.01.012. Epub 2019 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 30773395]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceArbaugh CJ, Brakebill A, Spain DA, Knowlton LM. Management of a traumatic splenic injury in the setting of polysubstance use and challenging social factors. Trauma surgery & acute care open. 2025:10(1):e001680. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2024-001680. Epub 2025 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 40041879]

Jenkins P, Zhong J, Harding J, Sorrell L, Smith J, Allgar V, Roobottom C. SPEED (SPlEnic Embolisation Decisions) study-Decision to treat acute traumatic splenic artery injury in the context of trauma protocol. PloS one. 2025:20(1):e0313138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0313138. Epub 2025 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 39775376]

Hemachandran N, Gamanagatti S, Sharma R, Shanmuganathan K, Kumar A, Gupta A, Kumar S. Revised AAST scale for splenic injury (2018): does addition of arterial phase on CT have an impact on the grade? Emergency radiology. 2021 Feb:28(1):47-54. doi: 10.1007/s10140-020-01823-z. Epub 2020 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 32705369]

Cinquantini F, Simonini E, Di Saverio S, Cecchelli C, Kwan SH, Ponti F, Coniglio C, Tugnoli G, Torricelli P. Non-surgical Management of Blunt Splenic Trauma: A Comparative Analysis of Non-operative Management and Splenic Artery Embolization-Experience from a European Trauma Center. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2018 Sep:41(9):1324-1332. doi: 10.1007/s00270-018-1953-9. Epub 2018 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 29671059]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBelli AK, Dönmez C, Özcan Ö, Dere Ö, Dirgen Çaylak S, Dinç Elibol F, Yazkan C, Yılmaz N, Nazlı O. Adherence to vaccination recommendations after traumatic splenic injury. Ulusal travma ve acil cerrahi dergisi = Turkish journal of trauma & emergency surgery : TJTES. 2018 Jul:24(4):337-342. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2017.84584. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30028492]

Buzelé R, Barbier L, Sauvanet A, Fantin B. Medical complications following splenectomy. Journal of visceral surgery. 2016 Aug:153(4):277-86. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2016.04.013. Epub 2016 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 27289254]

Luu S, Spelman D, Woolley IJ. Post-splenectomy sepsis: preventative strategies, challenges, and solutions. Infection and drug resistance. 2019:12():2839-2851. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S179902. Epub 2019 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 31571940]

Boyle TA, Rao KA, Horkan DB, Bandeian ML, Sola JE, Karcutskie CA, Allen C, Perez EA, Lineen EB, Hogan AR, Neville HL. Analysis of water sports injuries admitted to a pediatric trauma center: a 13 year experience. Pediatric surgery international. 2018 Nov:34(11):1189-1193. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4336-z. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30105495]

Asuquo ME, Etiuma AU, Bassey OO, Ugare G, Ngim O, Agbor C, Ikpeme A, Ndifon W. A Prospective Study of Blunt Abdominal Trauma at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2010 Apr:36(2):164-8. doi: 10.1007/s00068-009-9104-2. Epub 2009 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 26815692]

Madhavan S, Taylor JS, Chandler JM, Staudenmayer KL, Chao SD. Firearm Legislation Stringency and Firearm-Related Fatalities among Children in the US. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2019 Aug:229(2):150-157. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.02.055. Epub 2019 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 30928667]

Chahine AH, Gilyard S, Hanna TN, Fan S, Risk B, Johnson JO, Duszak R Jr, Newsome J, Xing M, Kokabi N. Management of Splenic Trauma in Contemporary Clinical Practice: A National Trauma Data Bank Study. Academic radiology. 2021 Nov:28 Suppl 1():S138-S147. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.11.010. Epub 2020 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 33288400]

Eldredge RS, Ochoa B, Notrica D, Lee J. National Management Trends in Pediatric Splenic Trauma - Are We There yet? Journal of pediatric surgery. 2024 Feb:59(2):320-325. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2023.10.024. Epub 2023 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 37953159]

Olsen A, Possfelt-Møller E, Jensen LR, Taudorf M, Rudolph SS, Preisler L, Penninga L. Follow-up strategies after non-operative treatment of traumatic splenic injuries: a systematic review. Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2024 Oct 21:409(1):315. doi: 10.1007/s00423-024-03504-8. Epub 2024 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 39432154]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWongweerakit O, Akaraborworn O, Sangthong B, Thongkhao K. Clinical parameters for the early detection of complications in patients with blunt hepatic and/or splenic injury undergoing non-operative management. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2024 Jun:50(3):847-855. doi: 10.1007/s00068-024-02460-8. Epub 2024 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 38294693]

Cunningham AJ, Lofberg KM, Krishnaswami S, Butler MW, Azarow KS, Hamilton NA, Fialkowski EA, Bilyeu P, Ohm E, Burns EC, Hendrickson M, Krishnan P, Gingalewski C, Jafri MA. Minimizing variance in Care of Pediatric Blunt Solid Organ Injury through Utilization of a hemodynamic-driven protocol: a multi-institution study. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2017 Dec:52(12):2026-2030. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.08.035. Epub 2017 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 28941929]

Ruscelli P, Buccoliero F, Mazzocato S, Belfiori G, Rabuini C, Sperti P, Rimini M. Blunt hepatic and splenic trauma. A single Center experience using a multidisciplinary protocol. Annali italiani di chirurgia. 2017:88():. pii: S0003469X17026483. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28604373]

Tugnoli G, Bianchi E, Biscardi A, Coniglio C, Isceri S, Simonetti L, Gordini G, Di Saverio S. Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury in adults: there is (still) a long way to go. The results of the Bologna-Maggiore Hospital trauma center experience and development of a clinical algorithm. Surgery today. 2015 Oct:45(10):1210-7. doi: 10.1007/s00595-014-1084-0. Epub 2014 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 25476466]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence