Introduction

Rhinosinusitis is the inflammation of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, typically resulting from infection, allergy, or other causes. Rhinosinusitis is classified into the following categories, based more on consensus rather than empirical research:[1]

- Acute: Symptoms lasting less than 4 weeks

- Subacute: Symptoms lasting between 4 and 12 weeks

- Chronic: Symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks

- Recurrent: Four episodes lasting less than 4 weeks with complete symptom resolution between episodes

Acute sinusitis involves inflammation of the lining of the paranasal sinuses. Because the sinus passages are connected to the nasal passages, the term rhinosinusitis is often more accurate. Acute rhinosinusitis is a frequently diagnosed condition, accounting for approximately 30 million primary care visits annually and contributing to an estimated $11 billion in healthcare costs. This condition is also a primary reason for antibiotic prescriptions in both the United States and worldwide. Given recent guidelines and concerns about antibiotic resistance and responsible antibiotic use, having clear treatment protocols for this common condition is essential for diagnosis.[2][3]

Acute rhinosinusitis caused by viral upper respiratory infections and noninfectious conditions should be distinguished from acute bacterial rhinosinusitis based on illness pattern and duration of illness. Acute sinusitis diagnosis depends on the presence of purulent nasal drainage for up to 4 weeks. The clinical challenge lies in the fact that neither purulent nasal drainage nor symptom duration is diagnostic for both bacterial and viral agents.[4][5] Most clinicians rely on the three main symptoms, including purulent nasal drainage, facial or dental pain, and nasal obstruction complaints; however, these do not lead to definitive diagnoses.[6][7] Evaluation should always include vital signs and a thorough examination of the head and neck. To complicate the clinical picture, up to 2% of patients with viral rhinosinusitis also develop a bacterial infection concurrently.[8] Finally, fever may be present with viral rhinosinusitis initially, but it also does not predict a bacterial infection.[7][9]

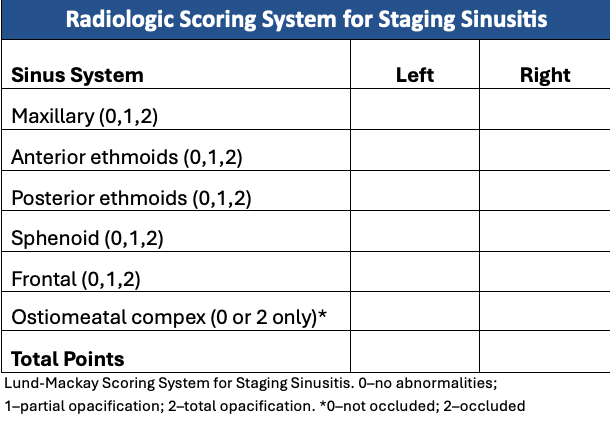

Generally, radiographic imaging has limited utility in acute rhinosinusitis unless there is evidence of a complication or an alternative diagnosis.[1] Plain film radiographs are less reliable than coronal computed tomographic (CT) scans when surgical intervention is needed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is generally not helpful unless a fungal infection or tumor is suspected. Ultrasound offers limited usefulness. Most otolaryngologists prefer fiberoptic sinus endoscopy combined with targeted culture in challenging cases.

Management typically involves symptomatic treatment and close monitoring in most cases. These measures include humidification, warm compresses, hydration, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and, in some cases, mucolytic agents to enhance patient comfort. Antihistamines are not advised, and decongestants should be used cautiously and only temporarily.

Although antibiotics are often presumed to be the preferred treatment, their use in acute bacterial rhinosinusitis remains a topic of discussion, as randomized controlled trials have not conclusively demonstrated significant advantages in employing antibiotics for the management of acute sinusitis.[10] Furthermore, systematic reviews of patients with radiologic or bacteriologic confirmation showed no significant difference in clinical resolution rates between those treated with amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate and those treated with cephalosporins or macrolides.[11][12][13]

In most cases of acute rhinosinusitis, surgical intervention is not required, and medical treatment remains the standard approach. Exceptions include patients who do not respond to medical management, show rapidly worsening symptoms, or have a suspicion of an abscess or complications involving the eyes or nervous system that could threaten the patient's safety or life.

Treatment may fail in many patients without close follow-up. Fortunately, complications are infrequent. Preventing complications such as mucoceles, osteomyelitis, and orbital and intracranial issues should be the top priority in patients showing unusual signs and symptoms. [14]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Paranasal sinuses have traditionally been considered physiologically sterile; however, research indicates that even healthy individuals may have sinus colonization.[15] Sinusitis is believed to begin with the obstruction and retention of mucus drainage, creating an environment conducive to infectious agents. Alternatively, it is proposed that organisms that may colonize the nasal cavity and nasopharynx could contaminate the sinuses if mucociliary clearance is compromised or disrupted.[16][17]

The duration of signs and symptoms arbitrarily distinguishes between acute and chronic sinusitis. Nonetheless, acute sinusitis is associated with infection, whereas chronic sinusitis is primarily characterized by inflammation.[18] Clinical discourse persists concerning the etiologies of both conditions. Nevertheless, it appears reasonable to consider that acute sinusitis may result from an underlying etiology induced by an infectious agent, such as viruses, bacteria, or, in rare cases, fungi.

Common Etiologic Agents in Rhinosinusitis

- Viruses (most common) [19]

- Rhinovirus

- Influenza virus

- Parainfluenza virus

- Adenovirus

- Coronavirus

- Respiratory syncytial virus

- Enterovirus

- Bacteria [20]

- Fungi: Rare, typically associated with allergic fungal sinusitis and similar to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis [26]

- Aspergillus species

- Alternaria species

- Bipolaris

- Curvularia species [27] (associated with intranasal drug use)

In immunosuppressed individuals—such as those with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, those with HIV-positive status, those undergoing active cancer treatment, and those on immunosuppressants after organ transplantation or managing rheumatologic conditions—a rare form of acute fungal sinusitis can occur, known as invasive fungal sinusitis.[28] Invasive fungal sinusitis is a highly aggressive infection with unclear treatment parameters and poor outcomes. Common fungal species linked to these cases include Mucor, Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, and Aspergillus. A distinction should be made between acute invasive fungal sinusitis, which typically occurs in immunosuppressed individuals, and allergic fungal sinusitis, which affects immunocompetent individuals as a mass-like lesion in the sinus cavity and often presents with chronic symptoms.

Epidemiology

Sinusitis is more common from early fall to late spring, making it one of the most prevalent medical conditions that carries a significant socioeconomic burden due to both direct and indirect costs.[29] Rhinosinusitis affects approximately 15% of the US population, or about 35 million people annually, and ranks as the fifth most common reason for prescribing antibiotics.[30][31] Acute bacterial sinusitis is likely underreported by patients and overdiagnosed and overtreated by clinicians.

Children typically experience more than 6 upper respiratory infections annually, with approximately 6% to 13% of these viral cases developing into acute bacterial sinusitis. Adults are less likely to develop bacterial sinusitis after a viral infection, but the rate could still be around 2%. Consequently, ongoing efforts focus on promoting responsible antibiotic use among healthcare providers to decrease unnecessary prescriptions and curb bacterial resistance.[32]

Some studies report that women have nearly twice the rate of rhinosinusitis compared to men, but others do not show a gender difference. Most studies do not differentiate between acute and chronic rhinosinusitis, and limited data exist, although some evidence suggests that the link between asthma and nasal polyps is stronger in women.[33][34]

Pathophysiology

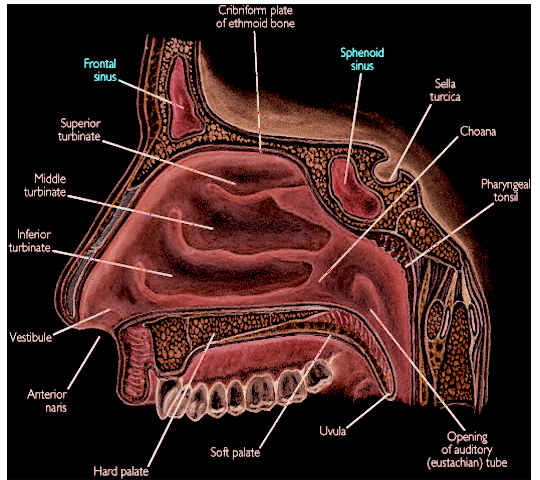

The nasal cavity is cylindrical and segmented by the nasal septum, which, in the majority of individuals, exhibits a natural S-shaped curvature and is composed of both bone and cartilage. Adults possess 4 paired paranasal sinus cavities—the ethmoid, sphenoid, frontal, and maxillary sinuses—each lined with pseudostratified columnar epithelium. The frontal sinuses typically develop between the ages of 5 and 6 and reach their full size after puberty. The sphenoid sinus begins to pneumatize at about 5 years but typically does not fully develop until between the ages of 20 and 30. In children, only the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses are present at birth.[35] The ethmoid sinus is separated from the orbit by only a thin layer of bone called the lamina papyracea. As a result, orbital infections typically originate from the ethmoid sinus, which is more common in younger children. Intracranial complications generally stem from the frontal sinuses and are more frequent in older children or adults.

The function of the paranasal sinuses has long been a topic of debate. Proposed theories include the following:[36]

- Decreasing the relative weight of the skull

- Increasing the resonance of the voice

- Providing a buffer against facial trauma

- Insulating sensitive structures from rapid temperature fluctuations in the nose

- Humidifying and heating inspired air

- Contributing to immunological defense

Nasal and paranasal anatomy varies among individuals, which increases the complexity of conditions affecting the paranasal sinuses. The paranasal sinuses are prone to inflammation and infection, and tissue overgrowth or polyps can develop as a result. Fortunately, cancers of the nasal and paranasal sinuses are rare. The pathophysiology of sinusitis is based on 3 main principles.

- Obstruction of sinus drainage

- Mucosal swelling

- Inflammation

- Rhinitis

- Systemic disorders

- Immunologic disorders

- Trauma

- Physical obstruction

- Nasal polyps

- Foreign bodies

- Deviated septum

- Enlarged turbinates

- Tumors

- Altered mucociliary transport mechanism through coordinated activity of ciliated columnar epithelium [37]

- Hypoxia resulting from sinus obstruction may disrupt ciliary function

- Other causes that may result in the loss of cilia or ciliary function

- High airflow

- Cold or dry air

- Low pH

- Cigarette smoke

- Drinking alcohol

- Dehydration

- Drugs, such as antihistamines and anticholinergics

- Infectious agents

- Environmental toxins

- Inflammatory mediators

- Contact between 2 mucosal surfaces

- Scarring

- Masses, lesions, or foreign bodies

- Genetic factors such as Kartagener syndrome [38]

- Altered quality or inadequate mucus

- Loss of humidity

- Overproduction of mucus

- Increased viscosity (e.g., cystic fibrosis) [39]

Acute sinusitis results from a combination of factors. Although most patients and healthcare professionals mainly focus on infectious agents when managing acute sinusitis, the underlying causes are likely more related to altered paranasal sinus or ciliary function or obstruction. Such factors may explain why most patients notice improvement with supportive measures, such as humidification, warm compresses, hydration, and nasal saline sprays and rinses, rather than antibiotics.

Histopathology

Healthy sinuses are lined with ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium, which uses cilia to clear debris, mucus, and other substances. The mucosal edema, infiltration of granulocytes and lymphocytes, squamous metaplasia, and fibroblast proliferation associated with acute rhinosinusitis interfere with this process.[40]

History and Physical

Clinical practice guidelines recommend that the initial diagnosis of acute sinusitis should focus on the following key considerations:[1]

- Exclusion of other causes of illness

- Evaluation for complications if the patient worsens or fails to improve with supportive care

- Differentiation between acute, chronic, and recurrent acute sinusitis

- Assessment for underlying comorbidities, such as:

- Asthma

- Cystic fibrosis

- Immunocompromise

- Ciliary dyskinesia

The 3 cardinal symptoms that are most sensitive and specific for acute rhinosinusitis are purulent nasal drainage accompanied by either nasal obstruction or facial pain, pressure, or fullness. These symptoms must be clearly distinguished from patients who present with general headache complaints. An isolated headache is not a typical symptom of sinusitis, except in rare cases of sphenoid sinusitis, which may present as an occipital or vertex headache and is usually chronic. In contrast, facial pressure is a more characteristic finding. The attentive clinician must actively gather this history from the patient to accurately identify the exact symptoms being experienced.[41]

When key symptoms last longer than 10 days or worsen after an initial improvement—known as double worsening—it may indicate acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Other signs of acute rhinosinusitis include cough, fatigue, hyposmia, anosmia, maxillary dental pain, and ear fullness or pressure. Anterior rhinoscopy may reveal mucopurulent discharge from the osteomeatal complex, which can be confirmed with sinus endoscopy.[1] Directed endoscopic culture may be beneficial, but it may also delay diagnosis.

Children show slight differences in the clinical signs of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Besides the 10-day duration, key symptoms, and double worsening, children are more prone to have fevers. Initially, nasal discharge may be watery and then become purulent. A viral upper respiratory infection accounts for approximately 80% of pediatric acute bacterial sinusitis cases.[42]

Severe symptoms are more indicative of a bacterial or systemic cause. Such symptoms include high fevers (over 39 °C or 102 °F) accompanied by purulent nasal discharge or facial pain lasting for 3 to 4 consecutive days at the start of the illness. Viral illnesses typically resolve after 3 to 5 days.[43]

Factors contributing to antibiotic resistance should be carefully considered when managing acute rhinosinusitis. These factors include:[44]

- Antibiotic use within the last month

- Hospitalization within the previous 5 days

- Employment in a healthcare setting

- Local patterns of antibiotic resistance are known to healthcare organizations in the community

Finally, it is important to assess whether the patient is at higher risk for complications. Risk factors include:[1]

- Comorbidities, such as cardiac, renal, or hepatic disease

- Immunocompromised states

- Age younger than 2 years or older than 65 years

Fungal acute rhinosinusitis is most commonly associated with fever, nasal obstruction or bleeding, and facial pain in immunocompromised patients, although it can also be asymptomatic. Refractory or severe symptoms in an immunocompromised patient should prompt consideration of this diagnosis.[45]

Evaluation

Acute sinusitis is a clinical diagnosis. Conventional diagnostic criteria for rhinosinusitis in adults require the patient to have at least 2 major symptoms or 1 major plus 2 or more minor symptoms. The criteria for children are similar, but there is greater emphasis on nasal discharge rather than nasal obstruction.

Signs and Symptoms

Major symptoms:

- Purulent anterior nasal discharge

- Purulent or discolored posterior nasal discharge

- Nasal congestion or obstruction

- Facial congestion or fullness

- Facial pain or pressure

- Hyposmia or anosmia

- Fever (for acute sinusitis only)

Minor symptoms:

- Headache

- Ear pain, pressure, or fullness

- Halitosis

- Dental pain

- Cough

- Fever (for subacute or chronic sinusitis)

- Fatigue

Among all physical findings, the purulence in the nasal cavity or posterior pharynx is the only finding shown to have diagnostic value. The initial diagnostic evaluation should include:[1]

- Measurement of vital signs, such as temperature, pulse, blood pressure, and respiratory rate

- Physical examination of the head and neck

- Particular attention should be paid to the presence or absence of the following:

- Altered (hyponasal) speech indicating nasal obstruction

- Swelling

- Redness of the skin due to congestion of the capillaries (erythema) or abnormally large fluid volume (edema) localized over the involved cheekbone or periorbital area

- Palpable cheek tenderness or percussion tenderness of the upper teeth

- Signs of extra-sinus involvement, including orbital or facial cellulitis, orbital protrusion, abnormalities of eye movement, and neck stiffness

Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis may be differentiated from viral upper respiratory infection using the following clinical guidance. This condition can be diagnosed if any of the 3 diagnostic criteria are true:[1][2][42][44]

- Duration of symptoms for more than 10 days

- High fever (over 39 °C or 102 °F) with purulent nasal discharge or facial pain that lasts for 3 to 4 consecutive days at the beginning of the illness

- Double worsening of symptoms within the first 10 days

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory studies have limited utility in the routine evaluation of acute sinusitis.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level may be elevated but are nonspecific.

- A complete blood cell count with differential may be within normal reference ranges.

- Laboratory studies are unnecessary unless there is a suspicion of cystic fibrosis (sweat chloride test),[46] ciliary dysfunction, or immunodeficiency (immunoglobulin studies or HIV serology)

Nasal cytology:

- Useful to distinguish allergic rhinitis, eosinophilia, and nasal polyposis [42]

- May be used to identify aspirin sensitivity (Samter syndrome) [47]

Nasal or sinus cultures:

- Limited value because of normal flora contamination unless:

- Signs of immunocompromise

- Failure to respond to medical management

- Signs of complications of sinusitis

- Endoscopic sinus culture at the middle meatus in adults may provide helpful information and may be similar to maxillary sinus puncture cultures.[48][49]

- Bedside maxillary sinus puncture cultures are valuable for patients with critical illness or immunocompromised conditions.[50]

Imaging:

- Plain film radiographs, including Waters, Caldwell, and Lateral views, may show diffuse opacification, mucosal thickening, or air-fluid levels. However, they are generally unnecessary and unreliable.[51]

- A CT scan is considered the gold standard for diagnosing chronic sinusitis. Still, it has poor specificity for acute sinusitis because nearly 50% asymptomatic patients and almost 90% of those with upper respiratory tract infections may show sinus air-fluid levels on the scan.[52][53]

- Coronal views are preferred for nasal and sinus anatomy.

- Delaying the CT scan until after the acute infection is preferred.

- A limited sinus CT scan may be preferred over a Waters view due to lower radiation exposure, especially in children.

- MRI scans have limited utility unless there is suspicion of a tumor or fungal infection. MRI is not as specific as CT for detecting bone pathology, but it may be used to evaluate intracranial or ophthalmologic extension of disease.

- Ultrasonography has limited utility. A-mode may help in the screening of maxillary sinus fluid. B-mode may also detect mucosal thickening or soft tissue mass.[54]

Sinus endoscopy:

- Most otolaryngologists prefer rigid sinus endoscopy with video imaging and recording or image capture.

- Sinus endoscopy helps identify purulence emanating from the middle meatus for culture, nasal polyps, structural abnormalities, fungal disease, or granulomatous disease.

- This technique is helpful in rare cases for paranasal biopsy.

Treatment / Management

Many patients with symptoms of upper respiratory tract infections often misinterpret their condition as acute sinusitis and request unnecessary antibiotics. Patients mainly aim to reduce or eliminate the severity and duration of symptoms. Clinicians should also focus on this goal but additionally aim to eradicate the infection and prevent complications, especially related to worsening systemic infections or ophthalmologic or intracranial sequelae.

Symptomatic treatment should be the first-line approach in most cases.

- Encourage use of:

- Nonnarcotic analgesics

- Humidification

- Hydration and proper nutrition

- Nasal saline irrigation [55]

- Intranasal nasal steroids [56]

- Decongestants (α-adrenergic)

- Guaifenesin (mucolytic) may offer symptom relief, but there is no evidence to show that it works for acute sinusitis.[59]

- Topical ipratropium bromide 0.06% may decrease rhinorrhea [60]

(A1)

Antimicrobial Therapy

- There is ongoing clinical debate regarding which patients may benefit from antibiotic therapy and when antibiotics should be initiated.[62][63]

- The duration of pain or illness related to acute bacterial rhinosinusitis does not consistently relate to initial treatment.[64]

- Adverse events were more common in patients treated with antibiotics.[65]

- Complications were similar regardless of the initial management approach.[66]

- Patterns of bacterial resistance should also be considered when selecting antibiotics. (A1)

Antibiotic choice and duration:

- A 5- to 10-day course of amoxicillin 500 mg 3 times daily is recommended as the first-line treatment.[1]

- Penicillins and cephalosporins appear to be equally effective.[10]

- Macrolide antibiotics and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are not recommended as initial treatment for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis because of the high rate of macrolide-resistant S pneumoniae.[67]

- Fluoroquinolones are not recommended as first-line treatment for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in patients without a penicillin allergy, as outcomes are similar to those of amoxicillin-clavulanate, and adverse events are more common in some studies.[68]

- High-dose amoxicillin with clavulanate (2 g orally twice daily or 90 mg/kg/d orally twice daily) is recommended if an amoxicillin-resistant organism is suspected.[44]

- Azithromycin may be less effective due to its anti-inflammatory effects, high rate of gastrointestinal adverse effects, and poor effectiveness against S pneumoniae and H influenzae.[69]

- The recommended duration of antibiotics is 10 days for most types; however, some studies have shown no difference between a 3- to 7-day course and a 6- to 10-day course.[70]

- Antibiotic therapy does not necessarily reduce the duration of symptoms or the rates of complications in adults. Many cases of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis can also resolve spontaneously within 2 weeks.[71] (A1)

For patients who do not respond to initial treatment for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis, it is imperative to reassess their condition and confirm the accuracy of the diagnosis. In cases where the diagnosis is confirmed or a deteriorating pattern of illness is observed, further evaluation should be conducted to exclude the possibility of orbital or intracranial spread of infection. Targeted endoscopic sinus cultures from the middle meatus may assist in guiding subsequent antibiotic therapy.

Suspicion of the rare invasive form of acute fungal rhinosinusitis necessitates urgent assessment and referral to otolaryngology, neurosurgery, and ophthalmology for biopsy. Such patients require an integrated approach involving both medical and surgical management (debridement), should histology establish this diagnosis.[72]

Surgical Therapy

- Most patients do not require surgical intervention for acute sinusitis.

- Exceptions include:

- Acute frontal sinusitis, when conservative therapy fails, including intravenous antibiotics for 3 to 5 days

- Acute maxillary sinusitis in immunocompromised or critically ill patients

- Isolated acute sphenoid sinusitis, when there is no improvement with intravenous antibiotics within 24 hours [73]

- Acute ethmoid sinusitis associated with any of the following:

- Failure to respond to medical management or presence of recurrent acute sinusitis

- Rapid disease progression

- Development of an abscess in the paranasal sinuses, orbit, or intracranial cavities

- Threat to survival

Differential Diagnosis

Several conditions can mimic the clinical presentation of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

- Upper respiratory infection

- Common cold (rhinovirus)

- Staphylococcal infection

- COVID-19

- H influenzae infections

- Influenza

- Moraxella catarrhalis infection

- Mucomycosis (Zygomycosis) (rare)

- Otitis media

- Human parainfluenza virus or other parainfluenza viruses

- Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis

- Asthma

- Bronchitis

- Bronchiectasis

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) [74]

- Ataxia-telangiectasia [75]

- Cystic fibrosis

- Immotile cilia syndrome [76]

- Kartagener syndrome [38]

- Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome [77]

- Yellow nail syndrome [78]

- Referred pain, such as dental infection or abscess

- Associated disorders

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Dental abscess

- Periapical abscess

- Migraine headache

- Tension headache

- Chronic invasive fungal sinusitis

- Sinonasal neoplasm

- Primary ciliary dyskinesia

- Unilateral choanal atresia

- Immune deficiency (immunoglobulins A and G)

- Nasal foreign body

- Deviated septum

- Enlarged inferior or middle turbinates

- Enlarged or infected tonsils and adenoids

Prognosis

Acute sinusitis and acute bacterial sinusitis are typically self-limited. Most patients recover with symptomatic treatment or antibiotics without long-term complications. Many individuals experience an episode of acute sinusitis and never take antibiotics. As a result, the true occurrence of acute sinusitis may be underestimated. An isolated case of acute sinusitis does not necessarily predispose a person to recurrent or chronic sinus disease.

Complications

Complications are uncommon, occurring in approximately 1 out of every 1000 cases.[2] Sinus infections can spread to the orbit, bone, or intracranial cavities.

Approximately 80% of orbitocranial complications occur in the orbit. These complications can lead to significant morbidity and mortality. The orbit is the most common site because it is separated from the ethmoid sinus by a very thin layer of bone. The Chandler classification is the most commonly used method for grading orbital complications of sinusitis infection, listed from least to most severe:[79]

- Preseptal cellulitis

- Orbital cellulitis

- Subperiosteal abscess

- Orbital abscess

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis

Intracranial complications are extremely rare and include the formation of a subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, meningitis, or a subdural empyema (the latter has a high mortality rate). Pott's puffy tumor is a subperiosteal abscess of the frontal bone, typically linked to osteomyelitis. Both complications typically originate from frontal sinus infections, spreading through the valveless diploic vein system via the bloodstream.

Finally, acute fungal sinusitis may occur in both noninvasive and invasive forms as a complication.[80] The invasive form can spread to surrounding structures and requires prompt recognition to prevent life-threatening consequences.[72]

Consultations

Referral to an otolaryngologist is typically unnecessary for uncomplicated acute sinusitis, as most cases are viral and resolve on their own. However, otolaryngology consultation is warranted in the following situations:

- Recurrent or chronic sinusitis

- Failure to improve despite medical therapy

- Severe, unrelenting pain

- Comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus or a possible immunologic or ciliary disorder without improvement

Referral to other specialties may also be indicated in the presence of potential complications:

- Orbital complications (ophthalmology consultation)

- Extraocular movement pain or dysfunction

- Periorbital or orbital erythema, swelling, or loss of vision

- Neurologic or intracranial complications (neurology or neurosurgery consultation)

- Mental status changes

- Intractable headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Vertigo

- Cranial nerve abnormalities

- Seizures

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients are more eager to understand and obtain detailed medical information about their health conditions, especially with the rise of Internet search engines. Patients and their families must be well-informed about the most relevant, current, consistent, and updated data regarding acute sinusitis and acute bacterial sinusitis. This knowledge helps them better understand their signs and symptoms, learn about diagnostic procedures, recognize when and how to use supportive measures, and decide the appropriate timing and necessity of antibiotic therapy. Additionally, patients should know when to seek medical help if treatments are ineffective. Education plays a key role in prevention by empowering patients to make informed decisions about their symptoms, which may indicate the presence of acute bacterial sinusitis that needs intervention, or signal possible comorbidities, systemic illnesses, or complications. By understanding the risks and benefits and adopting preventive strategies, patients can avoid adverse health outcomes and improve their overall health and well-being.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key points regarding acute sinusitis include the following:

- Most cases of acute sinusitis are viral and typically resolve with supportive care, often without the need for antibiotics.

- Antibiotic therapy should be used cautiously and selected wisely to prevent overuse and the development of antibiotic resistance.

- Patients who do not improve despite medical treatment or who exhibit signs of complications, other health issues, or systemic disease should be referred to an otolaryngologist.

- Acute sinusitis does not always progress to recurrent or chronic sinusitis.

- Surgical intervention for acute sinusitis is rare but may be necessary in severe, isolated infections.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Providing patient-centered care for individuals with acute sinusitis requires a collaborative, interprofessional approach involving clinicians, advanced practice practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers. Primarily, healthcare providers must possess the requisite clinical skills, comprehensive knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the nose and paranasal sinuses, and expertise in diagnosing, evaluating, and managing this condition. Such expertise encompasses proficiency in interpreting patient histories, physical examinations, laboratory results, and radiologic findings, as well as recognizing potential complications and understanding the nuances of viral and bacterial infections; inflammatory diseases, such as rhinitis and asthma; ciliary disorders; and immunocompromised states. Consultation with otolaryngology specialists, infectious disease specialists, ophthalmologists, neurologists, or neurosurgeons may be indicated depending on the clinical scenario and response to conservative treatments. An evidence-based, strategic approach coupled with individualized care plans tailored to each patient's specific circumstances is indispensable.

Ethical considerations hold paramount importance when determining treatment options, respecting patient autonomy in decision-making, and mitigating risks associated with antibiotic resistance. Defined responsibilities within the interprofessional team should ensure that each member contributes their specialized expertise to optimize patient outcomes. Effective interprofessional communication fosters a collaborative environment where information is shared, inquiries are addressed, and concerns are managed promptly.

Furthermore, effective care coordination is essential to ensuring seamless and efficient patient care. Clinicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers must collaborate to streamline the patient's journey from diagnosis through treatment and follow-up. An essential aspect of managing acute sinusitis involves encouraging patients to seek assistance when necessary and establishing realistic expectations regarding the immediate use of antibiotics. This coordination minimizes errors, reduces delays, and enhances patient safety, ultimately leading to improved outcomes, the prevention of serious complications, and the delivery of patient-centered care that prioritizes the well-being and satisfaction of those affected by acute sinusitis.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Army, Department of the Air Force, Department of Defense, or the US government.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, Brook I, Ashok Kumar K, Kramper M, Orlandi RR, Palmer JN, Patel ZM, Peters A, Walsh SA, Corrigan MD. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2015 Apr:152(2 Suppl):S1-S39. doi: 10.1177/0194599815572097. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25832968]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAring AM, Chan MM. Current Concepts in Adult Acute Rhinosinusitis. American family physician. 2016 Jul 15:94(2):97-105 [PubMed PMID: 27419326]

DeMuri G, Wald ER. Acute bacterial sinusitis in children. Pediatrics in review. 2013 Oct:34(10):429-37; quiz 437. doi: 10.1542/pir.34-10-429. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24085791]

Lacroix JS, Ricchetti A, Lew D, Delhumeau C, Morabia A, Stalder H, Terrier F, Kaiser L. Symptoms and clinical and radiological signs predicting the presence of pathogenic bacteria in acute rhinosinusitis. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2002 Mar:122(2):192-6 [PubMed PMID: 11936912]

van den Broek MF, Gudden C, Kluijfhout WP, Stam-Slob MC, Aarts MC, Kaper NM, van der Heijden GJ. No evidence for distinguishing bacterial from viral acute rhinosinusitis using symptom duration and purulent rhinorrhea: a systematic review of the evidence base. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2014 Apr:150(4):533-7. doi: 10.1177/0194599814522595. Epub 2014 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 24515968]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAxelsson A, Runze U. Symptoms and signs of acute maxillary sinusitis. ORL; journal for oto-rhino-laryngology and its related specialties. 1976:38(5):298-308 [PubMed PMID: 1034250]

Williams JW Jr, Simel DL, Roberts L, Samsa GP. Clinical evaluation for sinusitis. Making the diagnosis by history and physical examination. Annals of internal medicine. 1992 Nov 1:117(9):705-10 [PubMed PMID: 1416571]

Gwaltney JM Jr. Acute community-acquired sinusitis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1996 Dec:23(6):1209-23; quiz 1224-5 [PubMed PMID: 8953061]

Axelsson A, Runze U. Comparison of subjective and radiological findings during the course of acute maxillary sinusitis. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1983 Jan-Feb:92(1 Pt 1):75-7 [PubMed PMID: 6824285]

Ah-See K. Sinusitis (acute). BMJ clinical evidence. 2008 Mar 10:2008():. pii: 0511. Epub 2008 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 19450327]

Ahovuo-Saloranta A,Rautakorpi UM,Borisenko OV,Liira H,Williams JW Jr,Mäkelä M, Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Feb 11; [PubMed PMID: 24515610]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHenry DC, Riffer E, Sokol WN, Chaudry NI, Swanson RN. Randomized double-blind study comparing 3- and 6-day regimens of azithromycin with a 10-day amoxicillin-clavulanate regimen for treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2003 Sep:47(9):2770-4 [PubMed PMID: 12936972]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLuterman M, Tellier G, Lasko B, Leroy B. Efficacy and tolerability of telithromycin for 5 or 10 days vs amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for 10 days in acute maxillary sinusitis. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2003 Aug:82(8):576-80, 82-4, 586 passim [PubMed PMID: 14503094]

DelGaudio JM, Evans SH, Sobol SE, Parikh SL. Intracranial complications of sinusitis: what is the role of endoscopic sinus surgery in the acute setting. American journal of otolaryngology. 2010 Jan-Feb:31(1):25-8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.09.009. Epub 2009 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 19944895]

Brook I. Aerobic and anaerobic bacterial flora of normal maxillary sinuses. The Laryngoscope. 1981 Mar:91(3):372-6 [PubMed PMID: 7464398]

American Academy of Pediatrics. Subcommittee on Management of Sinusitis and Committee on Quality Improvement. Clinical practice guideline: management of sinusitis. Pediatrics. 2001 Sep:108(3):798-808 [PubMed PMID: 11533355]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDeMuri GP, Wald ER. Clinical practice. Acute bacterial sinusitis in children. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Sep 20:367(12):1128-34 [PubMed PMID: 22992076]

Lafci Fahrioglu S, VanKampen N, Andaloro C. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Sinus Function and Development. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422521]

Volpe S, Irish J, Palumbo S, Lee E, Herbert J, Ramadan I, Chang EH. Viral infections and chronic rhinosinusitis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2023 Oct:152(4):819-826. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2023.07.018. Epub 2023 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 37574080]

Brook I. Microbiology of sinusitis. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2011 Mar:8(1):90-100. doi: 10.1513/pats.201006-038RN. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21364226]

Anon JB. Treatment of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis caused by antimicrobial-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. The American journal of medicine. 2004 Aug 2:117 Suppl 3A():23S-28S [PubMed PMID: 15360094]

Verduin CM, Hol C, Fleer A, van Dijk H, van Belkum A. Moraxella catarrhalis: from emerging to established pathogen. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2002 Jan:15(1):125-44 [PubMed PMID: 11781271]

Brook I. The role of anaerobic bacteria in sinusitis. Anaerobe. 2006 Feb:12(1):5-12 [PubMed PMID: 16701606]

Little RE, Long CM, Loehrl TA, Poetker DM. Odontogenic sinusitis: A review of the current literature. Laryngoscope investigative otolaryngology. 2018 Apr:3(2):110-114. doi: 10.1002/lio2.147. Epub 2018 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 29721543]

Stein M, Caplan ES. Nosocomial sinusitis: a unique subset of sinusitis. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2005 Apr:18(2):147-50 [PubMed PMID: 15735419]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRoland LT, Humphreys IM, Le CH, Babik JM, Bailey CE, Ediriwickrema LS, Fung M, Lieberman JA, Magliocca KR, Nam HH, Teo NW, Thomas PC, Winegar BA, Birkenbeuel JL, David AP, Goshtasbi K, Johnson PG, Martin EC, Nguyen TV, Patel NN, Qureshi HA, Tay K, Vasudev M, Abuzeid WM, Hwang PH, Jafari A, Russell MS, Turner JH, Wise SK, Kuan EC. Diagnosis, Prognosticators, and Management of Acute Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis: Multidisciplinary Consensus Statement and Evidence-Based Review with Recommendations. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2023 Sep:13(9):1615-1714. doi: 10.1002/alr.23132. Epub 2023 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 36680469]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePham J, Kulla B, Johnson M. Invasive fungal infection caused by curvularia species in a patient with intranasal drug use: A case report. Medical mycology case reports. 2022 Sep:37():1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2022.05.005. Epub 2022 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 35620354]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFernandez IJ, Stanzani M, Tolomelli G, Pasquini E, Vianelli N, Baccarani M, Sciarretta V. Sinonasal risk factors for the development of invasive fungal sinusitis in hematological patients: Are they important? Allergy & rhinology (Providence, R.I.). 2011 Jan:2(1):6-11. doi: 10.2500/ar.2011.2.0009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22852108]

Halawi AM, Smith SS, Chandra RK. Chronic rhinosinusitis: epidemiology and cost. Allergy and asthma proceedings. 2013 Jul-Aug:34(4):328-334. doi: 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3675. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23883597]

Blackwell DL, Lucas JW, Clarke TC. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: national health interview survey, 2012. Vital and health statistics. Series 10, Data from the National Health Survey. 2014 Feb:(260):1-161 [PubMed PMID: 24819891]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBishai WR. Issues in the management of bacterial sinusitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002 Dec:127(6 Suppl):S3-9 [PubMed PMID: 12511854]

Fendrick AM, Saint S, Brook I, Jacobs MR, Pelton S, Sethi S. Diagnosis and treatment of upper respiratory tract infections in the primary care setting. Clinical therapeutics. 2001 Oct:23(10):1683-706 [PubMed PMID: 11726004]

Ference EH, Tan BK, Hulse KE, Chandra RK, Smith SB, Kern RC, Conley DB, Smith SS. Commentary on gender differences in prevalence, treatment, and quality of life of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy & rhinology (Providence, R.I.). 2015 Jan:6(2):82-8. doi: 10.2500/ar.2015.6.0120. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26302727]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchiller JS, Lucas JW, Ward BW, Peregoy JA. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vital and health statistics. Series 10, Data from the National Health Survey. 2012 Jan:(252):1-207 [PubMed PMID: 22834228]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRamadan HH, Chaiban R, Makary C. Pediatric Rhinosinusitis. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2022 Apr:69(2):275-286. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2022.01.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35337539]

Ogle OE, Weinstock RJ, Friedman E. Surgical anatomy of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2012 May:24(2):155-66, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2012.01.011. Epub 2012 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 22386856]

Bustamante-Marin XM, Ostrowski LE. Cilia and Mucociliary Clearance. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2017 Apr 3:9(4):. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028241. Epub 2017 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 27864314]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMishra M, Kumar N, Jaiswal A, Verma AK, Kant S. Kartagener's syndrome: A case series. Lung India : official organ of Indian Chest Society. 2012 Oct:29(4):366-9. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.102831. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23243352]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSafi C, Zheng Z, Dimango E, Keating C, Gudis DA. Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Cystic Fibrosis: Diagnosis and Medical Management. Medical sciences (Basel, Switzerland). 2019 Feb 22:7(2):. doi: 10.3390/medsci7020032. Epub 2019 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 30813317]

Berger G, Kattan A, Bernheim J, Ophir D, Finkelstein Y. Acute sinusitis: a histopathological and immunohistochemical study. The Laryngoscope. 2000 Dec:110(12):2089-94 [PubMed PMID: 11129027]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBarry A, Fahey T. Clinical Diagnosis of Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis. American family physician. 2020 Jun 15:101(12):758-759 [PubMed PMID: 32538592]

Wald ER, Applegate KE, Bordley C, Darrow DH, Glode MP, Marcy SM, Nelson CE, Rosenfeld RM, Shaikh N, Smith MJ, Williams PV, Weinberg ST, American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 1 to 18 years. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul:132(1):e262-80 [PubMed PMID: 23796742]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceArcimowicz M. Acute sinusitis in daily clinical practice. Otolaryngologia polska = The Polish otolaryngology. 2021 Aug 31:75(4):40-50. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0015.2378. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34552023]

Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, Brozek JL, Goldstein EJ, Hicks LA, Pankey GA, Seleznick M, Volturo G, Wald ER, File TM Jr, Infectious Diseases Society of America. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012 Apr:54(8):e72-e112. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir1043. Epub 2012 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 22438350]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBleier BS, Paz-Lansberg M. Acute and Chronic Sinusitis. The Medical clinics of North America. 2021 Sep:105(5):859-870. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2021.05.008. Epub 2021 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 34391539]

Dickinson KM, Collaco JM. Cystic Fibrosis. Pediatrics in review. 2021 Feb:42(2):55-67. doi: 10.1542/pir.2019-0212. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33526571]

Kim SD, Cho KS. Samter's Triad: State of the Art. Clinical and experimental otorhinolaryngology. 2018 Jun:11(2):71-80. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2017.01606. Epub 2018 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 29642688]

Kim DH, Kim SW, Basurrah MA, Hwang SH. Diagnostic Value of Middle Meatal Cultures versus Maxillary Sinus Culture in Acute and Chronic Sinusitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022 Oct 14:11(20):. doi: 10.3390/jcm11206069. Epub 2022 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 36294389]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBenninger MS, Payne SC, Ferguson BJ, Hadley JA, Ahmad N. Endoscopically directed middle meatal cultures versus maxillary sinus taps in acute bacterial maxillary rhinosinusitis: a meta-analysis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2006 Jan:134(1):3-9 [PubMed PMID: 16399172]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMendes Neto JA, Guerreiro VM, Hirai ER, Kosugi EM, Santos Rde P, Gregório LC. The role of maxillary sinus puncture on the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hospital-acquired rhinosinusitis. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2012 Jul-Aug:78(4):35-41 [PubMed PMID: 22936134]

Ebrahimnejad H, Zarch SH, Langaroodi AJ. Diagnostic Efficacy of Digital Waters' and Caldwell's Radiographic Views for Evaluation of Sinonasal Area. Journal of dentistry (Tehran, Iran). 2016 Sep:13(5):357-364 [PubMed PMID: 28127330]

Slavin RG, Spector SL, Bernstein IL, Kaliner MA, Kennedy DW, Virant FS, Wald ER, Khan DA, Blessing-Moore J, Lang DM, Nicklas RA, Oppenheimer JJ, Portnoy JM, Schuller DE, Tilles SA, Borish L, Nathan RA, Smart BA, Vandewalker ML, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. The diagnosis and management of sinusitis: a practice parameter update. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2005 Dec:116(6 Suppl):S13-47 [PubMed PMID: 16416688]

Smith SS, Ference EH, Evans CT, Tan BK, Kern RC, Chandra RK. The prevalence of bacterial infection in acute rhinosinusitis: a Systematic review and meta-analysis. The Laryngoscope. 2015 Jan:125(1):57-69. doi: 10.1002/lary.24709. Epub 2014 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 24723427]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYoung D, Morton R, Bartley J. Therapeutic ultrasound as treatment for chronic rhinosinusitis: preliminary observations. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2010 May:124(5):495-9. doi: 10.1017/S0022215109992519. Epub 2010 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 20053307]

Inanli S, Oztürk O, Korkmaz M, Tutkun A, Batman C. The effects of topical agents of fluticasone propionate, oxymetazoline, and 3% and 0.9% sodium chloride solutions on mucociliary clearance in the therapy of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in vivo. The Laryngoscope. 2002 Feb:112(2):320-5 [PubMed PMID: 11889391]

Meltzer EO, Bachert C, Staudinger H. Treating acute rhinosinusitis: comparing efficacy and safety of mometasone furoate nasal spray, amoxicillin, and placebo. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2005 Dec:116(6):1289-95 [PubMed PMID: 16337461]

Eccles R, Jawad MS, Jawad SS, Angello JT, Druce HM. Efficacy and safety of single and multiple doses of pseudoephedrine in the treatment of nasal congestion associated with common cold. American journal of rhinology. 2005 Jan-Feb:19(1):25-31 [PubMed PMID: 15794071]

Mortuaire G, de Gabory L, François M, Massé G, Bloch F, Brion N, Jankowski R, Serrano E. Rebound congestion and rhinitis medicamentosa: nasal decongestants in clinical practice. Critical review of the literature by a medical panel. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2013 Jun:130(3):137-44. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2012.09.005. Epub 2013 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 23375990]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlbrecht HH, Dicpinigaitis PV, Guenin EP. Role of guaifenesin in the management of chronic bronchitis and upper respiratory tract infections. Multidisciplinary respiratory medicine. 2017:12():31. doi: 10.1186/s40248-017-0113-4. Epub 2017 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 29238574]

El Khoury P, Abou Hamad W, Khalaf MG, El Hadi C, Assily R, Rassi S, Khoueir N. Ipratropium Bromide Nasal Spray in Non-Allergic Rhinitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Laryngoscope. 2023 Dec:133(12):3247-3255. doi: 10.1002/lary.30706. Epub 2023 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 37067019]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVenekamp RP, Thompson MJ, Hayward G, Heneghan CJ, Del Mar CB, Perera R, Glasziou PP, Rovers MM. Systemic corticosteroids for acute sinusitis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Mar 25:(3):CD008115. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008115.pub3. Epub 2014 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 24664368]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAnon JB, Jacobs MR, Poole MD, Ambrose PG, Benninger MS, Hadley JA, Craig WA, Sinus And Allergy Health Partnership. Antimicrobial treatment guidelines for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2004 Jan:130(1 Suppl):1-45 [PubMed PMID: 14726904]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYoung J, De Sutter A, Merenstein D, van Essen GA, Kaiser L, Varonen H, Williamson I, Bucher HC. Antibiotics for adults with clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet (London, England). 2008 Mar 15:371(9616):908-14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60416-X. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18342685]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLemiengre MB, van Driel ML, Merenstein D, Young J, De Sutter AI. Antibiotics for clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012 Oct 17:10():CD006089. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006089.pub4. Epub 2012 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 23076918]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSpurling GK, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, Foxlee R, Farley R. Delayed antibiotic prescriptions for respiratory infections. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Sep 7:9(9):CD004417. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004417.pub5. Epub 2017 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 28881007]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSkow M, Fossum GH, Høye S, Straand J, Brænd AM, Emilsson L. Hospitalizations and severe complications following acute sinusitis in general practice: a registry-based cohort study. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2023 Sep 5:78(9):2217-2227. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkad227. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37486144]

Jenkins SG, Farrell DJ, Patel M, Lavin BS. Trends in anti-bacterial resistance among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated in the USA, 2000-2003: PROTEKT US years 1-3. The Journal of infection. 2005 Dec:51(5):355-63 [PubMed PMID: 15950288]

Karageorgopoulos DE, Giannopoulou KP, Grammatikos AP, Dimopoulos G, Falagas ME. Fluoroquinolones compared with beta-lactam antibiotics for the treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2008 Mar 25:178(7):845-54. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071157. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18362380]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceElnaseeh W, Yousif Elamin M, Bandar Alsliham R, Bandar Alotaibi L, Abdulaziz Alaiban H, Fouzy Kattan M, Khalid Alquraini S, Khalid Alkhateeb A, Ahmed SSK, Jamal Alamer Z, Mohammed Alawdah A, Hamad Alhushayyish M, Jubayr Mohammed Altalhi M, Alhadidi NFA, Omar Alghamdi A. Efficacy and safety of azithromycin in treating sinusitis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trails. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2025 Apr:87(4):2324-2335. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000003182. Epub 2025 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 40212130]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFalagas ME, Karageorgopoulos DE, Grammatikos AP, Matthaiou DK. Effectiveness and safety of short vs. long duration of antibiotic therapy for acute bacterial sinusitis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2009 Feb:67(2):161-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03306.x. Epub 2008 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 19154447]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoisselle C, Rowland K. PURLs: Rethinking antibiotics for sinusitis: again. The Journal of family practice. 2012 Oct:61(10):610-2 [PubMed PMID: 23106063]

Dwyhalo KM, Donald C, Mendez A, Hoxworth J. Managing acute invasive fungal sinusitis. JAAPA : official journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2016 Jan:29(1):48-53. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000473374.55372.8f. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26704655]

Hnatuk LA, Macdonald RE, Papsin BC. Isolated sphenoid sinusitis: the Toronto Hospital for Sick Children experience and review of the literature. The Journal of otolaryngology. 1994 Feb:23(1):36-41 [PubMed PMID: 8170018]

Robson JC, Grayson PC, Ponte C, Suppiah R, Craven A, Judge A, Khalid S, Hutchings A, Watts RA, Merkel PA, Luqmani RA, DCVAS Study Group. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.). 2022 Mar:74(3):393-399. doi: 10.1002/art.41986. Epub 2022 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 35106964]

Petley E, Yule A, Alexander S, Ojha S, Whitehouse WP. The natural history of ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T): A systematic review. PloS one. 2022:17(3):e0264177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264177. Epub 2022 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 35290391]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHorani A, Ferkol TW. Understanding Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia and Other Ciliopathies. The Journal of pediatrics. 2021 Mar:230():15-22.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.040. Epub 2020 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 33242470]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCandotti F. Clinical Manifestations and Pathophysiological Mechanisms of the Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome. Journal of clinical immunology. 2018 Jan:38(1):13-27. doi: 10.1007/s10875-017-0453-z. Epub 2017 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 29086100]

Vignes S, Baran R. Yellow nail syndrome: a review. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2017 Feb 27:12(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0594-4. Epub 2017 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 28241848]

Knipping S, Hirt J, Hirt R. [Management of Orbital Complications]. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 2015 Dec:94(12):819-26. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1547285. Epub 2015 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 26308141]

Schubert MS. Allergic fungal sinusitis: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Medical mycology. 2009:47 Suppl 1():S324-30. doi: 10.1080/13693780802314809. Epub 2009 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 19330659]