Definition/Introduction

Prevention in health involves intervening to avoid disease and injury. Effective strategies for preventive health rely on accurate health statistics to enhance their impact. This activity outlines different levels of prevention and highlights lifestyle and behavioral modifications as key approaches to reducing disease risk.

The natural history of disease can be classified into 5 stages—underlying, susceptible, subclinical, clinical, and recovery/disability/death. Corresponding preventive health measures are categorized into similar stages, allowing for targeted interventions. These preventive measures include primary prevention, secondary prevention, and tertiary prevention. Gordon described these traditional stages of prevention as prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation, offering a clear and practical framework for structuring public health interventions.[1] In recent decades, a fourth category known as primordial prevention has been added. Together, these strategies aim to prevent the onset of disease through risk reduction and to mitigate the downstream complications of a manifested disease or injury.

Primordial Prevention

Primordial prevention aims to mitigate medical harm before it reaches its point of impact by addressing socioeconomic and environmental risks. These risks can be mitigated at the government or institutional level by restricting access to harmful and dangerous substances or educating individuals and the public on how to avoid adverse health consequences.[2]

Governments effectively reduce these dangerous health factors by taxing tobacco products or preventing the advertisement of these harmful substances. For example, Hong Kong’s reduction in tobacco advertising was associated with a subsequent decline in tobacco consumption.[3]

Many areas in continental Africa have significantly increased educational measures towards primary prevention. There is a significant difference between countries that receive preventive education on specific diseases and those that do not. Education of children on key topics, such as diet, exercise, and common diseases, has been statistically shown to help improve cardiovascular health in younger populations and reduce the risk of developing more serious illnesses later in life. These findings demonstrate the potential impact of childhood preventive education.

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention aims to reduce the risk of disease before it begins by targeting modifiable risk factors in individuals who are still healthy. In the case of cardiovascular disease (CVD), interventions include improving diet, increasing physical activity, avoiding tobacco use, and maintaining a healthy weight.

Research indicates that when combined, these lifestyle modifications can reduce the risk of coronary heart disease by more than 80%.[4] Additionally, sustained adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors—such as exercising regularly, eating a balanced diet, quitting smoking, and maintaining normal weight, blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose levels—has been associated with up to a 70% reduction in cardiovascular risk.[5] Despite this, fewer than 5% of individuals adopt and maintain these changes. Hospitals are well-positioned to help drive prevention efforts by offering services such as exercise counseling, nutritional support, smoking cessation programs, and emotional wellness resources. These strategies should be implemented before any cardiac event occurs. Healthcare providers are encouraged to recognize early risk factors and intervene proactively.

Creating a sustainable, health-focused lifestyle requires coordinated effort between patients and healthcare systems. When preventive strategies are prioritized and integrated into routine care, the overall risk of CVD can be meaningfully reduced across the population.

Secondary Prevention

Secondary prevention focuses on reducing the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events in patients who are already diagnosed with other diseases. Lifestyle modifications, when combined with appropriate pharmacotherapy, play a crucial role in achieving this goal. Evidence shows that exercise programs, smoking cessation, and adherence to heart-healthy diets significantly lower the risk of mortality and hospital readmission after myocardial infarction.

Research further emphasizes that cardiac rehabilitation and increased physical fitness are related to the reduction of cardiovascular mortality. Smoking cessation following a cardiac event can reduce mortality risk much more than high-intensity therapy. However, many patients continue to smoke after they are discharged from the hospital. Lack of emotional support and depression make recovery even harder, highlighting the need for targeted hospital-based programs.

Evidence supports the incorporation of lifestyle changes into everyday routine to improve overall cardiovascular health. Hospitals should implement these strategies as foundational, long-term measures to reduce the risk of repeated cardiovascular events.[6]

Table. Examples of Secondary Prevention Strategies

|

System |

Intervention |

Purpose |

|

Cardiovascular |

BP/lipid screening and post-MI stress testing |

Detect risk, guide treatment, and prevent recurrence |

|

Cancer |

Mammography, Pap/HPV, colonoscopy, and LDCT |

Early detection and intervention |

|

Infectious |

HIV/TB screening and post-exposure prophylaxis |

Identify latent or early infection and prevent spread |

|

Metabolic |

Glucose, HbA1c, and lipid panels |

Detect prediabetes and dyslipidemia |

|

Mental health |

Depression, substance use, and cognitive screening |

Early detection improves outcomes |

|

Musculoskeletal |

DEXA scan and fall risk assessment |

Prevent fractures and injuries |

|

Vision/hearing |

Diabetic eye exams, glaucoma screening, and hearing screening |

Prevent vision and hearing loss |

|

Oral health |

Dental exams and oral cancer screening |

Detect early disease and prevent progression |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; MI, myocardial infarction; HPV, human papillomavirus; LDCT, low-dose computed tomography; TB, tuberculosis; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

Tertiary Prevention

Tertiary prevention focuses on reducing the long-term impact of chronic diseases by minimizing complications, preventing disability, and improving overall quality of life. In rheumatic heart disease, this includes interventions such as surgical valve repair or replacement, anticoagulation monitoring, heart failure management, and access to rehabilitation services. These strategies become especially important once permanent cardiac damage has occurred.[7]

Evidence shows that tertiary prevention is not limited to advanced medical interventions but also includes system-level support to help patients adapt and recover after diagnosis. This support can involve structured follow-up appointments, emotional and psychosocial support, and guidance in resuming daily routines. In settings with a high burden of rheumatic heart disease, the absence of such services can lead to early mortality and significantly reduced life expectancy.

For healthcare programs to be truly effective, they must extend care beyond the initial treatment phase. Tertiary prevention plays a vital role in ongoing disease management by incorporating rehabilitation, socioeconomic support, and continuous monitoring. In cases of rheumatic heart disease and similar chronic conditions, these efforts are essential to sustaining long-term health and reducing preventable deaths.

Quaternary Prevention

Quaternary prevention aims to ensure that medical interventions offer more benefit than harm by protecting patients from unnecessary or excessive treatments. This approach emphasizes the need to apply ethical scrutiny to all stages of health care, including extreme or complex conditions, particularly in an era where expanding medical technology increases the risk of overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Unlike earlier forms of prevention, quaternary prevention serves as a safeguard against interventions that may unintentionally reduce quality of life. It builds upon tertiary prevention by introducing an ethical dimension: ensuring that interventions are not only effective but also appropriate. For example, some tertiary strategies, such as intensive glycemic control, have failed to improve outcomes and, in certain cases, have even increased mortality, highlighting the need for ongoing evaluation of medical decisions.[8]

A practical application of quaternary prevention is observed in sports medicine, where clinicians intentionally avoid unnecessary imaging or invasive procedures in athletes to minimize medical overuse and potential harm. This approach reinforces the principle that not all medical action is beneficial, and that restraint can be protective.[9]

Quaternary prevention reinforces the principle of first do no harm.[10] This approach requires careful clinical judgment, patient feedback, and a commitment to avoiding unnecessary complexity or interventions that may negatively impact well-being. Ultimately, it acts as a safety net within tertiary care to ensure that treatments remain safe, ethical, and patient-centered.

Extensions to the Prevention Stages Model

Primordial prevention: In 1978, a new preventive strategy called primordial prevention was proposed by Strasser.[11] This approach focuses on reducing risk factors targeted towards an entire population by addressing social and environmental conditions. Such measures are typically promoted through laws and national policy. Because primordial prevention is the earliest prevention modality, it is often aimed at children to decrease as much risk exposure as possible. Primordial prevention targets the underlying stage of natural disease by targeting the underlying social conditions that promote disease onset. An example includes improving access to an urban neighborhood with [12] safe sidewalks to promote physical activity, which, in turn, decreases risk factors for obesity, CVD, and type 2 diabetes. CVD is a primary cause of mortality and hence lends to avoiding risk factors a priori, a type of primordial prevention.[13]

Quaternary prevention: Quaternary prevention focuses on protecting patients from the potential harm of unnecessary or excessive medical interventions. Initially proposed by Marc Jamoulle, this concept recognizes that over-medicalization can sometimes do more harm than good.[8] For example, excessive diagnostic tests, over-prescription of medications, or unnecessary surgeries can lead to adverse health consequences. These consequences can include adverse effects and complications, increased costs, and psychological distress for patients.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

The leading non-episodic causes of death in the United States—CVD, cancer, and chronic lower respiratory diseases—remain the most pressing despite being largely preventable. These conditions underscore the urgent need to focus on prevention strategies that address behavioral, environmental, and social determinants of health. Yet several persistent barriers continue to limit the effectiveness of these strategies.

Populations in low socioeconomic status bear a disproportionate burden of disease and often lack access to preventive care.[12] This disparity highlights the necessity of prioritizing public health interventions, particularly in historically underserved communities. Studies consistently demonstrate an inverse relationship between socioeconomic status and healthy behaviors, such as smoking cessation, physical activity, and diet quality, underscoring ongoing health inequities driven by socioeconomic factors.

Fragmented guidance also poses a challenge. Globally, the World Health Organization promotes prevention frameworks for vaccination, screening, and population health. In the United States, multiple organizations contribute to preventive care efforts. The US Preventive Services Task Force publishes evidence-based guidelines for primary and secondary prevention. In contrast, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention leads initiatives in chronic disease prevention, tobacco cessation, and immunization. However, the sheer number of recommending bodies and frequent updates to clinical guidelines can burden healthcare providers and make implementation difficult across healthcare systems.

Patient participation is another key obstacle, particularly in primary and secondary prevention, which often targets asymptomatic individuals. Despite strong evidence supporting the safety and effectiveness of preventive measures, some patients remain hesitant due to fear of adverse effects, distrust of medical motives, or a lack of perceived personal benefit.[14] Cultural, social, and psychological factors all contribute to this reluctance. Culturally tailored counseling, shared decision-making, and motivational interviewing are effective tools for addressing these concerns and improving patient engagement.

Cost and access remain additional concerns. Although many preventive measures offer long-term savings by avoiding expensive treatments later on, the upfront financial burden can be significant for both healthcare systems and patients. In resource-limited settings, preventive screenings or follow-up care may be delayed or omitted entirely. Sustainable prevention programs should balance cost-effectiveness with accessibility and quality to ensure equitable implementation.

Lastly, although prevention is generally beneficial, the overuse of preventive services can result in unintended harm. Quaternary prevention aims to identify and minimize unnecessary interventions, such as overscreening, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment, that may lead to anxiety, iatrogenic harm, or unnecessary costs.[8] This approach ensures a balance between proactive care and avoiding medical excess that can compromise patient well-being.

Clinical Significance

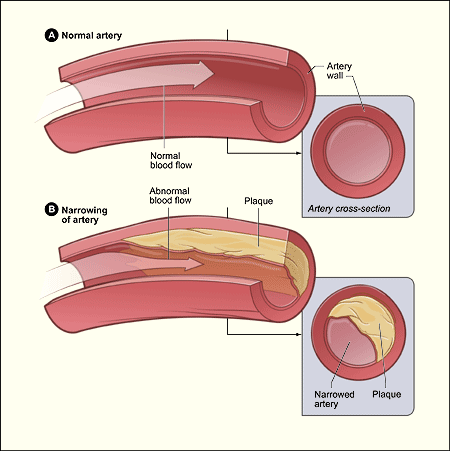

CVD, particularly coronary artery disease, remains the leading cause of death in developed countries. Despite substantial evidence supporting preventive care, risk factor management is underutilized in clinical practice.

A recent analysis by the Global Cardiovascular Risk Consortium estimated that 5 modifiable risk factors together account for over 50% of 10-year CVD incidence in both men and women.[15] This burden is measured using the Population Attributable Fraction, which estimates the proportion of disease cases in a population that can be prevented by eliminating a specific risk factor, assuming a causal relationship.

Table 2. Population Attributable Fraction of 10-Year Cardiovascular Disease Incidence by Risk Factor

| Risk Factor | Percent PAF Risk |

| Body mass index | 7.6 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 29.3 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol | 15.4 |

| Current smoking | 6.7 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15.2 |

Abbreviations: HDL, High-density lipoprotein; PAF, Population Attributable Fraction.

Reference for the table.[15]

Addressing these risk factors—hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and smoking—presents a powerful opportunity to shift healthcare upstream from costly interventions to effective prevention. Such efforts reduce morbidity, prolong life, and offer significant economic benefits by lowering healthcare utilization.

Despite this, preventive care often remains fragmented and underprioritized. For prevention to meaningfully reduce disease burden, it must be fully integrated into both clinical practice and health policy. This integration is essential for maximizing quality-adjusted life years, minimizing avoidable complications, and fulfilling the ethical imperative to prevent harm before treating disease (see Image. Coronary Artery Disease).

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Interprofessional Roles in Prevention: Nurses, Pharmacists, Lifestyle Coaches, and Multidisciplinary Teams

Nurses play a pivotal role in prevention, particularly in primary care, schools, public health, and community clinics. The responsibilities of nurses include:

- Conducting screenings (e.g., blood pressure, body mass index, and vaccination status) to improve early disease detection and outcomes.[16]

- Delivering health education during patient visits.

- Utilizing motivational interviewing techniques to support behavior change.

- Coordinating follow-up for high-risk or chronically ill patients.

Pharmacists significantly contribute to prevention by enhancing medication adherence, reviewing prescriptions for interactions, and administering vaccines. The involvement of pharmacists supports both primary and tertiary prevention goals. For example, pharmacist-led vaccination and screening programs have been shown to increase preventive uptake and improve health outcomes [17].Lifestyle medicine coaches, registered dietitians, and specialists play key roles in a multidisciplinary lifestyle medicine team, which combines expertise in nutrition, physical activity, behavioral change, and stress management. Interdisciplinary lifestyle programs have been shown to reduce obesity and cardiometabolic risk markers effectively. For example, a multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention targeting children and adolescents with moderate-to-severe obesity led to significant improvements in body mass index, body composition, and metabolic health over a 16-week program.[18]

In tertiary prevention, physical and occupational therapists play essential roles in rehabilitation, helping restore function and reduce long-term disability.

Prevention Education in Diverse Settings

Education-based prevention is implemented across schools and underserved communities.

- In schools, teachers, nurses, and counselors collaborate to introduce vital health concepts, covering nutrition, exercise, and avoidance of risky substances, during early development.[19]

- In low- and middle-income countries, community healthcare workers deliver door-to-door preventive education, helping bridge care gaps and promote health literacy in underserved regions.[20]

Ethical Considerations in Prevention

Delivering prevention ethically requires upholding equity, informed consent, and patient autonomy. Interventions should be evidence-based and culturally tailored, without imposing paternalism. Interprofessional teams should proactively work to reduce disparities by improving access for vulnerable populations, including those with low socioeconomic status, limited English proficiency, or low health literacy, to fulfill their ethical duties.

Integration Across Clinical and Community Settings

Prevention is not limited to primary care; it is embedded across various clinical settings.

- Primary care incorporates routine screenings, vaccinations, and lifestyle counseling.

- Specialty clinics, emergency departments, and inpatient units can play critical prevention roles, such as substance use screening, smoking cessation, and fall-risk assessments.

- Social workers and case managers often ensure that prevention continues seamlessly during care transitions.

Interprofessional Strategies to Advance Prevention

Effective prevention is rooted in team-based care. Proven strategies include the following:

- Standing orders enabling nurses and pharmacists to administer vaccines without clinician oversight.

- Collaborative care models that improve chronic disease management, such as teams managing hypertension, outperform solo practitioners in achieving blood pressure goals.

- Preventive care bundles are integrated into standardized care pathways, such as cancer screening reminders and postpartum follow-up protocols.

- Quality improvement programs that incentivize interdisciplinary teams to meet preventive health targets.

Enhancing Patient-Centered Outcomes and Team Performance

A team-based approach to prevention promotes care that is both proactive and well-coordinated, leading to improved patient safety and outcomes. When healthcare professionals work collaboratively to anticipate and address risks, prevention becomes more effective and patient-centered.

To support this model, training programs should emphasize interprofessional collaboration, communication skills, and shared accountability, essential competencies for delivering high-quality, preventive care.[21]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Gullotta TP. The what, who, why, where, when, and how of primary prevention. The journal of primary prevention. 1994 Sep:15(1):5-14. doi: 10.1007/BF02196343. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24254408]

Fielding R, Chee YY, Choi KM, Chu TK, Kato K, Lam SK, Sin KL, Tang KT, Wong HM, Wong KM. Declines in tobacco brand recognition and ever-smoking rates among young children following restrictions on tobacco advertisements in Hong Kong. Journal of public health (Oxford, England). 2004 Mar:26(1):24-30 [PubMed PMID: 15044569]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKa MM, Gaye ND, Ahadzi D, Baker-Smith CM, Ndao SCT, Wambugu V, Singh G, Gueye K, Seck D, Dia K, Allen NB, Ba A, Mboup WN, Yassine R, Guissé PM, Anne M, Aw F, Bèye SM, Diouf MT, Diaw M, Belkhadir J, Wone I, Kohen JE, Mbaye MN, Ngaide AA, Liyong EA, Sougou NM, Lalika M, Ale BM, Jaiteh L, Mekonnen D, Bukachi F, Lorenz T, Ntabadde K, Mampuya W, Houinato D, Kitara DL, Kane A, Seck SM, Fall IS, Tshilolo L, Samb A, Owolabi M, Diouf M, Lamptey R, Kengne AP, Maffia P, Clifford GD, Sattler ELP, Mboup MC, Jobe M, Gaye B. Promotion of Cardiovascular Health in Africa: The Alliance for Medical Research in Africa (AMedRA) Expert Panel. JACC. Advances. 2024 Dec:3(12):101376. doi: 10.1016/j.jacadv.2024.101376. Epub 2024 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 39817059]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRippe JM. Lifestyle Strategies for Risk Factor Reduction, Prevention, and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease. American journal of lifestyle medicine. 2019 Mar-Apr:13(2):204-212. doi: 10.1177/1559827618812395. Epub 2018 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 30800027]

Heinicke V, Halle M. [Lifestyle intervention in the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases]. Herz. 2020 Feb:45(1):30-38. doi: 10.1007/s00059-019-04886-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31993680]

Brinks J, Fowler A, Franklin BA, Dulai J. Lifestyle Modification in Secondary Prevention: Beyond Pharmacotherapy. American journal of lifestyle medicine. 2017 Mar-Apr:11(2):137-152. doi: 10.1177/1559827616651402. Epub 2016 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 30202327]

Vervoort D, Yilgwan CS, Ansong A, Baumgartner JN, Bansal G, Bukhman G, Cannon JW, Cardarelli M, Cunningham MW, Fenton K, Green-Parker M, Karthikeyan G, Masterson M, Maswime S, Mensah GA, Mocumbi A, Kpodonu J, Okello E, Remenyi B, Williams M, Zühlke LJ, Sable C. Tertiary prevention and treatment of rheumatic heart disease: a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group summary. BMJ global health. 2023 Oct:8(Suppl 9):. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012355. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37914182]

Martins C, Godycki-Cwirko M, Heleno B, Brodersen J. Quaternary prevention: reviewing the concept. The European journal of general practice. 2018 Dec:24(1):106-111. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1422177. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29384397]

Brito J, Mendes R, Figueiredo P, Marques JP, Beckert P, Verhagen E. Is it Time to Consider Quaternary Injury Prevention in Sports? Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 2023 Apr:53(4):769-774. doi: 10.1007/s40279-022-01765-1. Epub 2022 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 36178596]

Smith CM. Origin and uses of primum non nocere--above all, do no harm! Journal of clinical pharmacology. 2005 Apr:45(4):371-7 [PubMed PMID: 15778417]

Dahiya N, Sharma V, Kumar B, Thakur JS, Kumar S. Awareness and adherence to primary and primordial preventive measures among family members of patients with myocardial infarction-the unmet need for a "Preventive Clinic". Indian heart journal. 2020 Sep-Oct:72(5):454-458. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2020.07.017. Epub 2020 Jul 16 [PubMed PMID: 33189213]

Pampel FC, Krueger PM, Denney JT. Socioeconomic Disparities in Health Behaviors. Annual review of sociology. 2010 Aug:36():349-370 [PubMed PMID: 21909182]

Gillman MW. Primordial prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2015 Feb 17:131(7):599-601. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.014849. Epub 2015 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 25605661]

Hawley ST, Morris AM. Cultural challenges to engaging patients in shared decision making. Patient education and counseling. 2017 Jan:100(1):18-24. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.008. Epub 2016 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 27461943]

Global Cardiovascular Risk Consortium, Magnussen C, Ojeda FM, Leong DP, Alegre-Diaz J, Amouyel P, Aviles-Santa L, De Bacquer D, Ballantyne CM, Bernabé-Ortiz A, Bobak M, Brenner H, Carrillo-Larco RM, de Lemos J, Dobson A, Dörr M, Donfrancesco C, Drygas W, Dullaart RP, Engström G, Ferrario MM, Ferrières J, de Gaetano G, Goldbourt U, Gonzalez C, Grassi G, Hodge AM, Hveem K, Iacoviello L, Ikram MK, Irazola V, Jobe M, Jousilahti P, Kaleebu P, Kavousi M, Kee F, Khalili D, Koenig W, Kontsevaya A, Kuulasmaa K, Lackner KJ, Leistner DM, Lind L, Linneberg A, Lorenz T, Lyngbakken MN, Malekzadeh R, Malyutina S, Mathiesen EB, Melander O, Metspalu A, Miranda JJ, Moitry M, Mugisha J, Nalini M, Nambi V, Ninomiya T, Oppermann K, d'Orsi E, Pająk A, Palmieri L, Panagiotakos D, Perianayagam A, Peters A, Poustchi H, Prentice AM, Prescott E, Risérus U, Salomaa V, Sans S, Sakata S, Schöttker B, Schutte AE, Sepanlou SG, Sharma SK, Shaw JE, Simons LA, Söderberg S, Tamosiunas A, Thorand B, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Twerenbold R, Vanuzzo D, Veronesi G, Waibel J, Wannamethee SG, Watanabe M, Wild PS, Yao Y, Zeng Y, Ziegler A, Blankenberg S. Global Effect of Modifiable Risk Factors on Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. The New England journal of medicine. 2023 Oct 5:389(14):1273-1285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206916. Epub 2023 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 37632466]

Sargent GM, Forrest LE, Parker RM. Nurse delivered lifestyle interventions in primary health care to treat chronic disease risk factors associated with obesity: a systematic review. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2012 Dec:13(12):1148-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01029.x. Epub 2012 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 22973970]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJoseph Nosser A, Pate AN, Crocker AV, Malinowski SS, Brown MA, Ballou JM. Evaluation of Patient Adherence to Vaccine and Screening Recommendations during Community Pharmacist-led Medicare Annual Wellness Visits in a Family Medicine Clinic. Innovations in pharmacy. 2023:14(1):. doi: 10.24926/iip.v14i1.5180. Epub 2023 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 38035325]

Seo YG, Lim H, Kim Y, Ju YS, Lee HJ, Jang HB, Park SI, Park KH. The Effect of a Multidisciplinary Lifestyle Intervention on Obesity Status, Body Composition, Physical Fitness, and Cardiometabolic Risk Markers in Children and Adolescents with Obesity. Nutrients. 2019 Jan 10:11(1):. doi: 10.3390/nu11010137. Epub 2019 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 30634657]

Dwyer T, Viney R, Jones M. Assessing school health education programs. International journal of technology assessment in health care. 1991:7(3):286-95 [PubMed PMID: 1938190]

O'Donovan J, O'Donovan C, Kuhn I, Sachs SE, Winters N. Ongoing training of community health workers in low-income andmiddle-income countries: a systematic scoping review of the literature. BMJ open. 2018 Apr 28:8(4):e021467. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021467. Epub 2018 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 29705769]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceReeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, Goldman J, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Jun 22:6(6):CD000072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3. Epub 2017 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 28639262]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence