Introduction

Pituitary apoplexy is a condition with a hemorrhage or infarction of the pituitary gland. This disorder usually occurs in a preexisting pituitary adenoma.[1][2][3] The term pituitary apoplexy or apoplexia refers to the "sudden death" of the pituitary gland, usually caused by an acute ischemic infarction or hemorrhage. Pearce Bailey described the first case of pituitary tumor-associated hemorrhage in 1898. Still, the term pituitary apoplexy, referring to necrosis and bleeding into pituitary tumors, was first used in 1950 by Brougham et al.[4] Pituitary apoplexy is a medical and surgical emergency in many cases; prompt identification and evaluation of this condition are imperative to improve patient outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

A preexisting pituitary adenoma is usually present in most cases of pituitary apoplexy. In most cases, the patients are unaware of the presence of a pituitary tumor.[5] Several predisposing or contributing factors for pituitary apoplexy include:

- Endocrine stimulation tests [6][7]

- Bromocriptine or cabergoline treatment [8][9]

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone treatment [10]

- Lumbar fusion with the surgery being performed in the prone position [11][12]

- Pregnancy [13][14]

- Prior pituitary irradiation [15]

- Anticoagulation [16]

- Thrombocytopenia [17][18]

- Erectile dysfunction medication use [19][20]

Notably, Sheehan syndrome is a condition that occurs in postpartum women, in which there is necrosis of the pituitary gland secondary to ischemia that occurs after significant bleeding during childbirth. This syndrome will present with adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism, and hypopituitarism, but rarely does the patient experience visual changes. This entity is often not considered pituitary apoplexy because the gland does not have a preexisting tumor, and visual symptoms are infrequent.

Epidemiology

The reported incidence of pituitary apoplexy varies significantly from 1.5% to 27.7% in cases of pituitary adenoma, but many reports do not distinguish between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. When symptomatic cases only are included, the incidence approaches 10%.[2][21][22][23] If neuroimaging studies detect a nonsymptomatic intratumoral hemorrhage, the incidence increases to 26%. Apoplexy in pituitary adenomas is rare and is estimated to be 0.2% annually. Tumors larger than 10 mm have a higher risk of hemorrhage, as do those tumors where rapid growth has been documented.[24] Most patients range in age from 37 to 58 years.[25] There is a male-to-female ratio approaching 2:1.[23][25][26]

Pathophysiology

Hemorrhage results in acute tumor expansion, which produces most of the clinical symptoms. Visual symptoms are caused by direct compression of the optic nerves or chiasm, and the sudden disruption of the release of the pituitary hormones causes hormonal dysfunction. Several theories have been proposed to explain the ischemic and hemorrhagic changes found in the tumor and the normal gland. Although several proposed mechanisms are considered separately, each theory probably contributes to some combined process that ultimately produces the apoplexy.

One theory postulates that the compression of the superior hypophyseal artery and its branches against the diaphragma sella leads to ischemia of the anterior pituitary gland and the tumor.[2][3][27] Another theory proposes that the fine pituitary vascular network is compressed by the tumor located within the small intrasellar compartment, causing ischemia, necrosis, and hemorrhage.[2][3][28] Lastly, another theory suggests that the rapid expansion of the tumor outgrows its vascular supply, resulting in ischemia and necrosis.[2][3][29]

Histopathology

Pituitary apoplexy is a syndrome that results from hemorrhage or infarction into the pituitary gland or, more often, into a pituitary adenoma. Histologically, there is hemorrhage or infarcted, dead tissue seen within the gland or tumor that is examined. The tissue studies can demonstrate necrosis, hemorrhage, or both. Ruptured blood vessels can be seen in the presence of blood in either the gland or the surrounding tissue. The presence of necrosis suggests that tissue infarction has occurred. If the source of the hemorrhage is an adenoma, tumor cells may be present, which are nonfunctioning or often stain positive for prolactin on immunohistochemistry, indicating that the tumor is a prolactinoma. Inflammatory cells can be identified, suggesting that there is an ongoing immune response to the hemorrhage or infarction.

History and Physical

A sudden onset of headache located behind the eyes is the most common symptom associated with pituitary apoplexy.[3][30] Several mechanisms have been postulated to explain the headache in pituitary apoplexy and include the involvement of the superior division of the trigeminal nerve located within the cavernous sinus, meningeal irritation, dura mater compression, or expansion of the walls of the sella. Other symptoms include decreased visual acuity, hemianopia, diplopia, ptosis, nausea and vomiting, altered mental status, and hormonal dysfunction.[30][31][32][33] Many patients complain of double vision, which is caused by extrinsic compression of one or more of the extraocular nerves. The oculomotor nerve is the most commonly affected extraocular nerve.[25] Patients will have ptosis and lateral eye deviation, often accompanied by pupillary dilation of the affected eye if the oculomotor nerve is involved.

In pituitary apoplexy, the clinical problem that can result with the greatest impact is the lack of secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which occurs in more than two-thirds of the patients with apoplexy. The lack of ACTH secretion causes a cessation of cortisol secretion by the adrenal gland, which produces a variety of symptoms called "adrenal crisis."[2][3] Clinically, the patient may have nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, bradycardia, hypotension, hypothermia, lethargy, and, on occasion, coma.

Evaluation

The following workup should be included in any suspected case of pituitary apoplexy:

- Computed tomographic (CT) scan

- A noncontrast head CT scan is usually the initial imaging study performed because it can be easily obtained. This study will show a sellar/suprasellar mass associated with hyperdense intralesional hemorrhage. Ischemia or necrosis of the gland/tumor cannot usually be visualized on CT.

- A contrast-enhanced CT scan is performed afterwards to delineate the presence and size of a tumor. Hemorrhagic components and contrast-enhancing portions of the tumor are hyperdense compared to the brain on CT.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

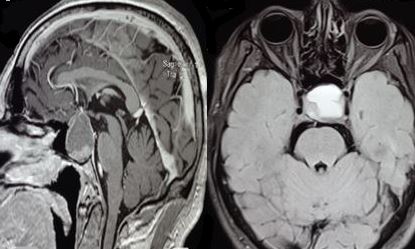

- A brain MRI is performed to define better the full extent of the mass in multiple scan projections, making MRI the diagnostic imaging modality of choice.[2][25] MRI can easily identify hemorrhagic and necrotic areas (see Image. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Pituitary Apoplexy). The characteristic brain MRI findings in pituitary apoplexy are an enlarged sellar/suprasellar mass with variable degrees of peripheral enhancement surrounding a hypointense center that is suggestive of blood. Diffusion-weighted imaging provides information regarding the consistency of the tumor and can identify ischemic or necrotic tissue after arterial occlusion has occurred.[2] With hemorrhagic apoplexy, T1-weighted MRI shows a sellar/suprasellar lesion with intralesional areas of high signal intensity indicative of blood. At the same time, infarction demonstrates low signal intensity (see Image. T1-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Pituitary Apoplexy).[3] The MRI gradient-echo sequence T2-star weighted (T2*W) is very sensitive for detecting deposits of hemosiderin.[2]

- Hormonal evaluation

Treatment / Management

The immediate medical management of pituitary apoplexy begins with stabilization, including careful assessment and correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalances to maintain hemodynamic stability, along with prompt corticosteroid replacement therapy.[34][35] Corticosteroids should be administered to all patients, even in the absence of adrenal crisis symptoms, to address potential secondary adrenal insufficiency and reduce edema around the optic apparatus. Recommended dosing consists of an initial intravenous hydrocortisone bolus of 100 to 200 mg, followed by 50 to 100 mg every 6 hours, or a continuous infusion of 2 to 4 mg/hour after the initial bolus.[3]

The optimal management of the pituitary mass remains debated. Some advocate for early transsphenoidal decompression in all patients, while others support a conservative approach in those with stable visual function and preserved consciousness.[36] Emergency surgical intervention is indicated for patients with progressive neurological decline, hypothalamic involvement, or worsening visual deficits. When visual acuity loss is stable, decompression can be delayed but ideally performed within 1 week.[37] Conservative management may be appropriate for patients with improving or stable ophthalmoplegia.[38][39] Microscopic endonasal or sublabial transsphenoidal surgery is a commonly used surgical approach.(A1)

For extensive tumors and those extending over the chiasm or laterally into the temporal fossa, a craniotomy should be used to achieve a maximal surgical resection. Endoscopic endonasal approaches for pituitary apoplexy are often effective.[32][40][41] Patients operated on using the endoscopic approach have a similar visual outcome success rate, but a better endocrinological outcome, as the tumoral component can be removed from areas such as the cavernous sinus that are inaccessible endoscopically.[42] Occasionally, an endoscopic approach may not be possible if the collaboration between an otolaryngologist and the neurosurgeon necessary for surgery cannot be arranged. In pediatric cases, pituitary tumor apoplexy tends to follow a more aggressive course than in adults, and early surgical intervention may reduce recurrence and improve prognosis.[43][44] A recently proposed 5-grade classification system, based on the spectrum of clinical presentation, may help guide individualized treatment decisions and predict outcomes.[45] (B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Several conditions have to be excluded as they can present with similar visual, ophthalmoplegic, and headache symptoms that occur in pituitary apoplexy. Some of the conditions will only require medical treatment, while in others, the surgical treatment is completely different. These conditions include:

Prognosis

Pituitary apoplexy can be a life-threatening condition if it is not detected early and treated promptly. The overall mortality is 1.6% to 1.9%. Visual acuity, visual field defects, and ophthalmoplegia improve in most patients after conservative management and surgical decompression. After surgery, such improvement can be observed in the immediate postoperative period and often continues for several weeks. Visual recovery has been reported to be less likely in patients presenting with monocular or binocular blindness.

Although the visual outcome appears to be better with early intervention as compared to delayed surgery, others have found that visual deficits, resolution of oculomotor nerve palsy, recovery from hypopituitarism, or nonneuroendocrine signs and symptoms such as headache and encephalopathy do not depend on the timing of surgery.[53][54] A complete restoration of the oculomotor palsy usually occurs within 3 months, while abducens nerve palsy usually requires 6 months.[25] Overall, visual improvement is seen in 75% to 85% of patients, recovery of normal vision occurs in 38% of patients, and resolution of preoperative oculomotor palsies occurs in 81% of patients.[32]

Gross total resection and a short duration of preoperative headaches are clinical predictors of improved postoperative headaches.[55] Hormonal replacement therapy is required in 80% of patients.[1][23][54] In some cases that are treated conservatively, spontaneous remission of the tumor has occurred, and surgery was not required.[56][57] This may be the result of ischemic necrosis of the tumoral tissue.

Complications

The following can be complications of pituitary apoplexy:

Consultations

The following consultations may be required:

- Neurosurgery

- Hospitalist

- Ophthalmology

- Endocrinology

Deterrence and Patient Education

While pituitary apoplexy is often an unpredictable, acute event, certain preventive measures and patient education strategies can help reduce risk in susceptible individuals and improve early recognition. Patients with known pituitary macroadenomas—particularly those with large, nonfunctioning tumors or tumors with suprasellar extension—should be counseled on the potential risk of apoplexy, especially in the context of precipitating factors such as anticoagulation therapy, major surgery, significant head trauma, pregnancy, or dynamic pituitary function testing. Clinicians should carefully weigh the benefits and risks of anticoagulation and optimize perioperative management in these high-risk patients.

Education should focus on recognizing early warning symptoms, including sudden severe headache, visual changes, nausea, vomiting, or altered consciousness, and the importance of seeking urgent medical evaluation. Patients should understand that prompt diagnosis and treatment can significantly improve neurological and endocrine outcomes. Those with a known tumor should be informed of the possibility of intratumoral hemorrhage and encouraged to maintain regular follow-up visits with their endocrinologist and neurosurgeon. Any acute visual change or significant headache should prompt immediate medical assessment.

Long-term follow-up is essential, as patients with pituitary apoplexy may have persistent endocrine deficiencies. Pituitary function should be reassessed at 4 to 8 weeks after the event, with ongoing management of any hormonal deficits. Visual acuity, extraocular movements, and visual fields must also be evaluated. Imaging surveillance is recommended, with MRI at 3 to 6 months post-apoplexy to assess for residual tumor, followed by annual MRI scans for up to 5 years. In the postoperative setting, patients should receive education on signs of recurrence, proper hormone replacement, and the use of stress-dose corticosteroids during illness or surgery if adrenal insufficiency is present.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Optimal management of pituitary apoplexy requires rapid recognition, decisive action, and coordinated care among multiple disciplines. Physicians—particularly endocrinologists, neurosurgeons, ophthalmologists, and emergency medicine specialists—must identify the abrupt onset of severe headache, visual changes, and altered mental status, and promptly initiate targeted diagnostic imaging. Advanced clinicians and nurses play a critical role in continuous neurologic and visual monitoring, hemodynamic stabilization, and administration of high-dose corticosteroids to prevent adrenal crisis. Pharmacists contribute by ensuring accurate dosing, screening for drug interactions, and facilitating timely medication availability, while rehabilitation specialists assist in early recovery planning for patients with residual deficits.

Effective interprofessional communication is central to patient safety and optimal outcomes in pituitary apoplexy. Rapid activation of multidisciplinary response pathways—linking emergency, endocrine, and neurosurgical teams—ensures that imaging, endocrine stabilization, and surgical decisions occur immediately. Structured handoffs, shared electronic documentation, and real-time updates facilitate seamless care transitions, while early involvement of ophthalmology guides visual prognosis and follow-up needs. By aligning expertise across disciplines, healthcare teams can minimize delays, reduce complication risks, improve visual and hormonal outcomes, and enhance patient confidence through clear, coordinated communication.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ranabir S, Baruah MP. Pituitary apoplexy. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 2011 Sep:15 Suppl 3(Suppl3):S188-96. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.84862. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22029023]

Briet C, Salenave S, Bonneville JF, Laws ER, Chanson P. Pituitary Apoplexy. Endocrine reviews. 2015 Dec:36(6):622-45. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1042. Epub 2015 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 26414232]

Briet C, Salenave S, Chanson P. Pituitary apoplexy. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America. 2015 Mar:44(1):199-209. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2014.10.016. Epub 2014 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 25732655]

BROUGHAM M, HEUSNER AP, ADAMS RD. Acute degenerative changes in adenomas of the pituitary body--with special reference to pituitary apoplexy. Journal of neurosurgery. 1950 Sep:7(5):421-39 [PubMed PMID: 14774761]

Biousse V, Newman NJ, Oyesiku NM. Precipitating factors in pituitary apoplexy. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2001 Oct:71(4):542-5 [PubMed PMID: 11561045]

Kuzu F, Unal M, Gul S, Bayraktaroglu T. Pituitary Apoplexy due to the Diagnostic Test in a Cushing"s Disease Patient. Turkish neurosurgery. 2018:28(2):323-325. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.16730-15.1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27593808]

Gheorghe AM, Trandafir AI, Ionovici N, Carsote M, Nistor C, Popa FL, Stanciu M. Pituitary Apoplexy in Patients with Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors (PitNET). Biomedicines. 2023 Feb 23:11(3):. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11030680. Epub 2023 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 36979658]

Ghadirian H, Shirani M, Ghazi-Mirsaeed S, Mohebi S, Alimohamadi M. Pituitary Apoplexy during Treatment of Prolactinoma with Cabergoline. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Jan-Mar:13(1):93-95. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.181130. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29492132]

Aydin B, Aksu O, Asci H, Kayan M, Korkmaz H. A RARE CAUSE OF PITUITARY APOPLEXY: CABERGOLINE THERAPY. Acta endocrinologica (Bucharest, Romania : 2005). 2018 Jan-Mar:14(1):113-116. doi: 10.4183/aeb.2018.113. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31149244]

Keane F, Egan AM, Navin P, Brett F, Dennedy MC. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist-induced pituitary apoplexy. Endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism case reports. 2016:2016():160021. doi: 10.1530/EDM-16-0021. Epub 2016 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 27284452]

Joo C, Ha G, Jang Y. Pituitary apoplexy following lumbar fusion surgery in prone position: A case report. Medicine. 2018 May:97(19):e0676. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010676. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29742711]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAkakın A, Yılmaz B, Ekşi MŞ, Kılıç T. A case of pituitary apoplexy following posterior lumbar fusion surgery. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2015 Nov:23(5):598-601. doi: 10.3171/2015.3.SPINE14792. Epub 2015 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 26252784]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJemel M, Kandara H, Riahi M, Gharbi R, Nagi S, Kamoun I. Gestational pituitary apoplexy: Case series and review of the literature. Journal of gynecology obstetrics and human reproduction. 2019 Dec:48(10):873-881. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2019.05.005. Epub 2019 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 31059861]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAnnamalai AK, Jeyachitra G, Jeyamithra A, Ganeshkumar M, Srinivasan KG, Gurnell M. Gestational Pituitary Apoplexy. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 2017 May-Jun:21(3):484-485. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_8_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28553611]

Yu J, Li Y, Quan T, Li X, Peng C, Zeng J, Liang S, Huang M, He Y, Deng Y. Initial Gamma Knife radiosurgery for nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas: results from a 26-year experience. Endocrine. 2020 May:68(2):399-410. doi: 10.1007/s12020-020-02260-1. Epub 2020 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 32162186]

Ly S, Naman A, Chaufour-Higel B, Patey M, Arndt C, Delemer B, Litre CF. Pituitary apoplexy and rivaroxaban. Pituitary. 2017 Dec:20(6):709-710. doi: 10.1007/s11102-017-0828-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28831662]

Thomas M, Robert A, Rajole P, Robert P. A Rare Case of Pituitary Apoplexy Secondary to Dengue Fever-induced Thrombocytopenia. Cureus. 2019 Aug 5:11(8):e5323. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5323. Epub 2019 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 31428546]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBalaparameswara Rao SJ, Savardekar AR, Nandeesh BN, Arivazhagan A. Management dilemmas in a rare case of pituitary apoplexy in the setting of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Surgical neurology international. 2017:8():4. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.198731. Epub 2017 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 28217383]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUneda A, Hirashita K, Yunoki M, Yoshino K, Date I. Pituitary adenoma apoplexy associated with vardenafil intake. Acta neurochirurgica. 2019 Jan:161(1):129-131. doi: 10.1007/s00701-018-3763-x. Epub 2018 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 30542775]

Kajal S, Ahmad YES, Halawi A, Gol MAK, Ashley W. Pituitary apoplexy: a systematic review of non-gestational risk factors. Pituitary. 2024 Aug:27(4):320-334. doi: 10.1007/s11102-024-01412-0. Epub 2024 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 38935252]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMohr G, Hardy J. Hemorrhage, necrosis, and apoplexy in pituitary adenomas. Surgical neurology. 1982 Sep:18(3):181-9 [PubMed PMID: 7179072]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMohanty S, Tandon PN, Banerji AK, Prakash B. Haemorrhage into pituitary adenomas. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1977 Oct:40(10):987-91 [PubMed PMID: 591978]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMurad-Kejbou S, Eggenberger E. Pituitary apoplexy: evaluation, management, and prognosis. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2009 Nov:20(6):456-61. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283319061. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19809320]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFernández-Balsells MM, Murad MH, Barwise A, Gallegos-Orozco JF, Paul A, Lane MA, Lampropulos JF, Natividad I, Perestelo-Pérez L, Ponce de León-Lovatón PG, Erwin PJ, Carey J, Montori VM. Natural history of nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas and incidentalomas: a systematic review and metaanalysis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011 Apr:96(4):905-12. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1054. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21474687]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRicciuti R, Nocchi N, Arnaldi G, Polonara G, Luzi M. Pituitary Adenoma Apoplexy: Review of Personal Series. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Jul-Sep:13(3):560-564. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_344_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30283505]

Nawar RN, AbdelMannan D, Selman WR, Arafah BM. Pituitary tumor apoplexy: a review. Journal of intensive care medicine. 2008 Mar-Apr:23(2):75-90. doi: 10.1177/0885066607312992. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18372348]

Cardoso ER, Peterson EW. Pituitary apoplexy: a review. Neurosurgery. 1984 Mar:14(3):363-73 [PubMed PMID: 6369168]

Rovit RL, Fein JM. Pituitary apoplexy: a review and reappraisal. Journal of neurosurgery. 1972 Sep:37(3):280-8 [PubMed PMID: 5069376]

Epstein S, Pimstone BL, De Villiers JC, Jackson WP. Pituitary apoplexy in five patients with pituitary tumours. British medical journal. 1971 May 1:2(5756):267-70 [PubMed PMID: 5572390]

Grzywotz A, Kleist B, Möller LC, Hans VH, Göricke S, Sure U, Müller O, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I. Pituitary apoplexy - A single center retrospective study from the neurosurgical perspective and review of the literature. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2017 Dec:163():39-45. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.10.006. Epub 2017 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 29055223]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWichlińska-Lubińska M, Kozera G. Pituitary apoplexy. Neurologia i neurochirurgia polska. 2019:53(6):413-420. doi: 10.5603/PJNNS.a2019.0054. Epub 2019 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 31745969]

Zoli M, Milanese L, Faustini-Fustini M, Guaraldi F, Asioli S, Zenesini C, Righi A, Frank G, Foschini MP, Sturiale C, Pasquini E, Mazzatenta D. Endoscopic Endonasal Surgery for Pituitary Apoplexy: Evidence On a 75-Case Series From a Tertiary Care Center. World neurosurgery. 2017 Oct:106():331-338. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.06.117. Epub 2017 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 28669873]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBarkhoudarian G, Kelly DF. Pituitary Apoplexy. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2019 Oct:30(4):457-463. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2019.06.001. Epub 2019 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 31471052]

Veldhuis JD, Hammond JM. Endocrine function after spontaneous infarction of the human pituitary: report, review, and reappraisal. Endocrine reviews. 1980 Winter:1(1):100-7 [PubMed PMID: 6785084]

Iglesias P. Pituitary Apoplexy: An Updated Review. Journal of clinical medicine. 2024 Apr 24:13(9):. doi: 10.3390/jcm13092508. Epub 2024 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 38731037]

Donegan D, Erickson D. Revisiting Pituitary Apoplexy. Journal of the Endocrine Society. 2022 Sep 1:6(9):bvac113. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvac113. Epub 2022 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 35928242]

Brown NJ, Patel S, Gendreau J, Abraham ME. The role of intervention timing and treatment modality in visual recovery following pituitary apoplexy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2024 Dec:170(3):469-482. doi: 10.1007/s11060-024-04717-z. Epub 2024 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 39503840]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAlmeida JP, Sanchez MM, Karekezi C, Warsi N, Fernández-Gajardo R, Panwar J, Mansouri A, Suppiah S, Nassiri F, Nejad R, Kucharczyk W, Ridout R, Joaquim AF, Gentili F, Zadeh G. Pituitary Apoplexy: Results of Surgical and Conservative Management Clinical Series and Review of the Literature. World neurosurgery. 2019 Oct:130():e988-e999. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.055. Epub 2019 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 31302273]

Seo Y, Kim YH, Dho YS, Kim JH, Kim JW, Park CK, Kim DG. The Outcomes of Pituitary Apoplexy with Conservative Treatment: Experiences at a Single Institution. World neurosurgery. 2018 Jul:115():e703-e710. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.139. Epub 2018 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 29709755]

Pangal DJ, Chesney K, Memel Z, Bonney PA, Strickland BA, Carmichael J, Shiroishi M, Jason Liu CS, Zada G. Pituitary Apoplexy Case Series: Outcomes After Endoscopic Endonasal Transsphenoidal Surgery at a Single Tertiary Center. World neurosurgery. 2020 May:137():e366-e372. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.01.204. Epub 2020 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 32032792]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZhan R, Li X, Li X. Endoscopic Endonasal Transsphenoidal Approach for Apoplectic Pituitary Tumor: Surgical Outcomes and Complications in 45 Patients. Journal of neurological surgery. Part B, Skull base. 2016 Feb:77(1):54-60. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1560046. Epub 2015 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 26949589]

Teixeira JC, Lavrador J, Simão D, Miguéns J. Pituitary Apoplexy: Should Endoscopic Surgery Be the Gold Standard? World neurosurgery. 2018 Mar:111():e495-e499. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.12.103. Epub 2017 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 29288106]

Culpin E, Crank M, Igra M, Connolly DJA, Dimitri P, Mirza S, Sinha S. Pituitary tumour apoplexy within prolactinomas in children: a more aggressive condition? Pituitary. 2018 Oct:21(5):474-479. doi: 10.1007/s11102-018-0900-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30014342]

Zhang N, Zhou P, Meng Y, Ye F, Jiang S. A retrospective review of 34 cases of pediatric pituitary adenoma. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2017 Nov:33(11):1961-1967. doi: 10.1007/s00381-017-3538-3. Epub 2017 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 28721598]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJho DH, Biller BM, Agarwalla PK, Swearingen B. Pituitary apoplexy: large surgical series with grading system. World neurosurgery. 2014 Nov:82(5):781-90. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.06.005. Epub 2014 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 24915069]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMartinez Santos J, Hannay M, Olar A, Eskandari R. Rathke's Cleft Cyst Apoplexy in Two Teenage Sisters. Pediatric neurosurgery. 2019:54(6):428-435. doi: 10.1159/000503112. Epub 2019 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 31634887]

Jung HN, Kim ST, Kong DS, Suh SI, Ryoo I. Rathke Cleft Cysts with Apoplexy-Like Symptoms: Clinicoradiologic Comparisons with Pituitary Adenomas with Apoplexy. World neurosurgery. 2020 Oct:142():e1-e9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.03.086. Epub 2020 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 32217176]

Schooner L, Wedemeyer MA, Bonney PA, Lin M, Hurth K, Mathew A, Liu CJ, Shiroishi M, Carmichael JD, Weiss MH, Zada G. Hemorrhagic Presentation of Rathke Cleft Cysts: A Surgical Case Series. Operative neurosurgery (Hagerstown, Md.). 2020 May 1:18(5):470-479. doi: 10.1093/ons/opz239. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31504863]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePedro B, Patrícia T, Aldomiro F. Pituitary Apoplexy May Be Mistaken for Temporal Arteritis. European journal of case reports in internal medicine. 2019:6(11):001261. doi: 10.12890/2019_001261. Epub 2019 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 31890705]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChoudhury M, Eligar V, DeLloyd A, Davies JS. A case of pituitary apoplexy masquerading as subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clinical case reports. 2016 Mar:4(3):255-7. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.488. Epub 2016 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 27014446]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLaw-Ye B, Pyatigorskaya N, Leclercq D. Pituitary Apoplexy Mimicking Bacterial Meningitis with Intracranial Hypertension. World neurosurgery. 2017 Jan:97():748.e3-748.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.10.032. Epub 2016 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 27756666]

Shabas D, Sheikh HU, Gilad R. Pituitary Apoplexy Presenting as Status Migrainosus. Headache. 2017 Apr:57(4):641-642. doi: 10.1111/head.13046. Epub 2017 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 28181226]

Abdulbaki A, Kanaan I. The impact of surgical timing on visual outcome in pituitary apoplexy: Literature review and case illustration. Surgical neurology international. 2017:8():16. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.199557. Epub 2017 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 28217395]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRutkowski MJ, Kunwar S, Blevins L, Aghi MK. Surgical intervention for pituitary apoplexy: an analysis of functional outcomes. Journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Aug:129(2):417-424. doi: 10.3171/2017.2.JNS1784. Epub 2017 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 28946177]

Suri H, Dougherty C. Presentation and Management of Headache in Pituitary Apoplexy. Current pain and headache reports. 2019 Jul 29:23(9):61. doi: 10.1007/s11916-019-0798-5. Epub 2019 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 31359174]

Eichberg DG, Di L, Shah AH, Kaye WA, Komotar RJ. Spontaneous preoperative pituitary adenoma resolution following apoplexy: a case presentation and literature review. British journal of neurosurgery. 2020 Oct:34(5):502-507. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2018.1529737. Epub 2018 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 30450986]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSouteiro P, Belo S, Carvalho D. A rare case of spontaneous Cushing disease remission induced by pituitary apoplexy. Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2017 May:40(5):555-556. doi: 10.1007/s40618-017-0645-7. Epub 2017 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 28251551]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGambaracci G, Rondoni V, Guercini G, Floridi P. Pituitary apoplexy complicated by vasospasm and bilateral cerebral infarction. BMJ case reports. 2016 Jun 21:2016():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-216186. Epub 2016 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 27329099]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAbbas MS, AlBerawi MN, Al Bozom I, Shaikh NF, Salem KY. Unusual Complication of Pituitary Macroadenoma: A Case Report and Review. The American journal of case reports. 2016 Oct 6:17():707-711 [PubMed PMID: 27708253]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZou Z, Liu C, Sun B, Chen C, Xiong W, Che C, Huang H. Surgical treatment of pituitary apoplexy in association with hemispheric infarction. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2015 Oct:22(10):1550-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.03.049. Epub 2015 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 26213287]