Introduction

Pellegrini-Stieda lesions refer to heterotopic ossification involving the medial collateral ligament (MCL), typically located at or near its proximal insertion on the medial femoral condyle. These lesions are most often identified radiographically as elongated or curvilinear calcifications that develop following trauma, chronic traction, or repetitive stress to the MCL origin. The lesions are named after early 20th-century surgeons Augusto Pellegrini and Alfred Stieda.[1] However, the first radiologic description of this process was documented by Köhler in 1903, predating the more widely recognized publications of Pellegrini (1905) and Stieda (1908).

The term "Pellegrini-Stieda lesion" specifically denotes the radiographic finding of ossification at the MCL origin.[2] In contrast, Pellegrini-Stieda disease (or syndrome) refers to the clinical condition characterized by such ossification in conjunction with medial knee pain, stiffness, or restricted range of motion (ROM).[3] While many lesions are asymptomatic and incidentally discovered on imaging, symptomatic cases are usually associated with prior MCL injury, particularly grade II or III sprains, and may present weeks to months after the initial trauma. Adjacent structures may also be affected, with calcific deposits reported in the distal adductor magnus tendon.[4]

Distinguishing between a radiographic lesion and the symptomatic disease is clinically important. Conservative treatment, including rest, physical therapy, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), is effective in most cases, though surgical excision may be required for persistent or functionally limiting symptoms.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The pathogenesis of Pellegrini-Stieda lesions is generally attributed to injury of the MCL, initiating acute inflammation followed by delayed dystrophic ossification at or near the ligament’s femoral origin. The inciting trauma is classically described as a macrotraumatic event, either direct or indirect, producing valgus stress and mechanical disruption of superficial or deep MCL fibers. This mechanism aligns with Köhler’s 1903 observations linking the characteristic ossification to athletic injuries involving valgus loading of the knee.

Although macrotrauma remains the predominant mechanism, microrepetitive damage may also contribute to Pellegrini-Stieda disease. Reports in the physiatric literature describe forceful manipulation of a stiff knee during postsurgical rehabilitation or therapeutic interventions provoking ossific changes in the MCL, particularly in patients presenting with new-onset medial knee pain, edema, or ROM limitation during recovery.[5][6] In such cases, the pathophysiology may reflect cumulative low-grade traction injury rather than a single traumatic insult.

Pellegrini-Stieda-like ossifications have also been documented in patients without direct knee trauma but with central neurological conditions, such as spinal cord or traumatic brain injury.[7] In these populations, periarticular calcifications require cautious interpretation, as the radiographic appearance may be confounded by heterotopic ossification or myositis ossificans, both of which occur more frequently in neurologically compromised individuals. Differentiation from true Pellegrini-Stieda lesions often requires clinical history, temporal evolution, and advanced imaging.

Epidemiology

Although the precise incidence of Pellegrini-Stieda lesions remains undefined, a 7-year retrospective review of a clinical radiology database from the University of Colorado and the University of Alabama at Birmingham identified 332 knee radiograph reports containing the term “Pellegrini-Stieda,” suggesting the lesion is not uncommon in clinical practice.[8] Epidemiologic data indicate a male predominance, most often affecting adults aged 25 to 40. This distribution may reflect the higher risk of ligamentous injury in physically active men during peak musculoskeletal activity years.[9]

Pathophysiology

Whether triggered by a single macrotraumatic event or repetitive microtrauma, the initiating insult in Pellegrini-Stieda lesions leads to calcific ossification of soft tissue structures adjacent to the medial femoral condyle. In patients with spinal cord or traumatic brain injury, heterotopic ossification in this region may arise through neurogenic mechanisms involving a complex interplay of humoral, neural, and local factors. Proposed contributors include tissue hypoxia, altered calcium metabolism (such as hypercalcemia), dysregulated sympathetic activity, prolonged immobilization, and subsequent mechanical mobilization.[10]

Traditionally, Pellegrini-Stieda lesions have been attributed to ossification within the proximal portion of the MCL at its femoral origin. However, this stereotypical localization has been increasingly questioned.[11] Studies incorporating magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cadaveric dissection have revealed more heterogeneous distribution patterns, often with ossific foci located inferior to the classical site of the MCL origin.[12] Mendes et al proposed a 4-type imaging-based classification according to the anatomical distribution of the ossified lesion, as follows:

- Type 1: Beak-like ossification arising from the medial femoral condyle and extending inferiorly into the MCL

- Type 2: Teardrop-shaped ossification confined within the MCL with no attachment to the femur

- Type 3: Elongated ossification located superior to the femoral condyle within the distal adductor magnus tendon

- Type 4: Beak-like ossification resembling type 1, but extending into both the MCL and the adductor magnus tendon

This classification reflects a growing consensus that ossification in Pellegrini-Stieda lesions is not necessarily confined to the MCL. Increasing evidence demonstrates frequent involvement of adjacent structures, including the adductor magnus tendon, medial head of the gastrocnemius, and medial patellofemoral ligament, suggesting that exclusive attribution to the MCL is anatomically oversimplified.

Although many Pellegrini-Stieda lesions are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on imaging, some patients develop localized medial knee pain, often with ROM restriction and joint effusion. When these symptoms accompany radiographic evidence of ossification, the condition is termed "Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome."

History and Physical

A representative clinical scenario of Pellegrini-Stieda disease involves a young man in his late 20s to early 30s presenting with right medial knee pain and ROM limitation. He reports a direct knee-to-knee collision to the medial aspect of the right knee, sustained a few weeks (usually 3) earlier during a recreational soccer match. The initial trauma caused acute pain that improved with rest and cryotherapy, but he now notes localized medial knee discomfort, stiffness, and reduced joint mobility. This delayed symptom onset after a valgus injury is characteristic of Pellegrini-Stieda disease, corresponding to the expected timeline of posttraumatic MCL ossification.

Evaluation

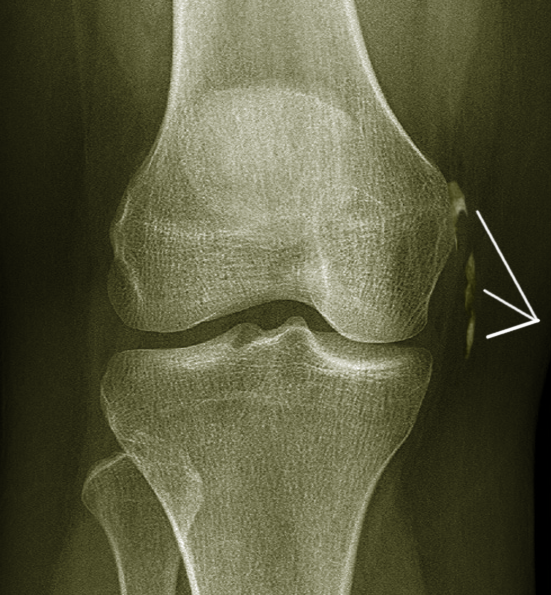

The diagnosis of Pellegrini-Stieda lesions is primarily radiographic, typically confirmed by the characteristic Pellegrini-Stieda sign on anteroposterior or oblique knee radiographs in conjunction with medial knee pain or ROM restriction. Radiographically, this sign appears as a linear or curvilinear calcification within the soft tissues medial to the femoral condyle, reflecting ossification at the MCL origin (see Image. Medial Collateral Ligament Calcification). Calcific ossification generally does not appear until about 3 weeks after the initial injury, consistent with the timeline of dystrophic mineralization.[13]

Differentiation from a medial femoral condyle avulsion fracture is important, as the latter results from traction injury with a bony fragment avulsed from its site of ligamentous or tendinous attachment. Although both entities may share overlapping locations and symptoms, their management and prognostic implications differ significantly.

MRI is a valuable adjunct in ambiguous or early cases. The images may demonstrate bone marrow edema at the medial femoral condyle with ossified or enthesopathic changes of the MCL, which often appear thickened and hypointense on T1-weighted sequences due to calcific infiltration. MRI also helps exclude intraarticular pathology or avulsion fractures.

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography has also gained attention as a noninvasive, dynamic modality for detecting Pellegrini-Stieda lesions. This modality provides real-time visualization of soft tissue calcifications and may demonstrate associated perilesional edema or hyperemia, supporting diagnosis in symptomatic individuals.

Treatment / Management

Conservative Management

The natural course of Pellegrini-Stieda lesions typically spans 5 to 6 months, during which the ossified lesion undergoes progressive maturation. Management is largely dictated by symptom severity and degree of functional impairment. In cases presenting with mild-to-moderate symptoms, initial treatment is conservative and focuses on symptom relief and functional restoration. The regimen includes activity modification to avoid exacerbating movements, physiotherapy aimed at maintaining and improving ROM and muscular strength, and administration of NSAIDs to alleviate pain and reduce inflammation.

Intraarticular corticosteroid injections may be considered as adjuncts to conservative therapy, particularly for patients with persistent pain and localized inflammation. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous calcific lavage, augmented by autologous platelet-rich plasma injection, has shown promise in cases refractory to standard conservative modalities.[14] This minimally invasive technique has been reported in isolated case literature to provide both clinical and radiographic improvement, though further studies are needed to establish broader efficacy.[15](B3)

Surgical Management

Patients with severe or function-limiting symptoms unresponsive to conservative measures may require surgical intervention. Operative treatment typically involves excision of the ossified or calcified lesion, with or without concurrent MCL repair or reconstruction, depending on the size and anatomical integration of the lesion. Arthroscopic techniques have also been described in the literature, including minimally invasive debridement and adhesiolysis, offering potential benefits of reduced morbidity and faster postoperative recovery.[16](B3)

However, surgical outcomes remain variable. In their earlier investigation, Kulowski and Riebel reported inconsistent results with a notable recurrence rate, raising concerns about the long-term durability of surgical excision. In contrast, Pellegrini’s original series and a subsequent update by Kulowski reported more favorable outcomes. Importantly, excision of large ossified masses may compromise MCL integrity, often requiring reconstruction to restore medial stability.

A case report documented the resolution of a Pellegrini-Stieda lesion following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Notably, the lesion, present preoperatively, disappeared during the postoperative course. This regression was hypothesized to result from biomechanical correction achieved by the procedure, which restored normal joint loading in a previously varus-aligned osteoarthritic knee.[17](B3)

Another case report described a combined therapeutic approach using extracorporeal shock wave therapy and iontophoresis. This intervention was effective in reducing both pain and calcific deposition associated with Pellegrini-Stieda disease.[18](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Several radiological and clinical entities can mimic Pellegrini-Stieda disease and should be considered to avoid misdiagnosis. Radiologically, differentials include MCL calcification, which is typically benign and associated with metabolic disorders without prior trauma, as well as calcification of the distal adductor magnus tendon, myositis ossificans, heterotopic ossification, and medial femoral condyle avulsion fracture. Clinically, conditions that may present with overlapping symptoms include MCL sprain, medial meniscal tear, medial patellofemoral injuries, knee osteoarthritis, and tendinitis involving the semimembranosus, semitendinosus, or gastrocnemius. Careful correlation of patient history, physical examination findings, and imaging characteristics enables the clinician to distinguish Pellegrini-Stieda disease from these mimicking conditions.

Prognosis

Most cases of Pellegrini-Stieda disease resolve within 5 to 6 months with conservative management, including NSAIDs, corticosteroid injections, and ROM exercises. However, severe refractory cases may require surgical intervention.

Complications

Untreated Pellegrini-Stieda disease may result in restricted knee joint ROM and contracture, leading to gait abnormalities, impaired activities of daily living, and chronic pain. Some studies have reported poor surgical outcomes, with high recurrence rates or ligamentous defects after large lesion excisions requiring further reconstruction.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Treatment for most patients involves a rehabilitative program focused on gradual restoration of knee ROM, stretching, and strengthening of muscles acting on the knee joint and the MCL. Therapy plans must be tailored to prevent contracture from MCL calcification. Cryotherapy can help manage pain and inflammation. Outcomes are favorable in most cases, with return to activity within 3 to 6 months after surgery. Recurrence of ossification and persistent stiffness may occur if early mobilization is not achieved. Regular assessments are essential to monitor progress in pain and ROM.

Consultations

Initial consultation with a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician is optimal for guidance in developing an appropriate rehabilitation program. Referral to an orthopedic surgeon for consideration of calcification excision is warranted if symptoms persist despite conservative measures and targeted rehabilitation.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be encouraged to continue stretching and ROM exercises through a structured home program after formal physical therapy. Sedentary behavior and prolonged joint immobilization should be discouraged. Temporary reduction of physical labor and limitation to light activity for pain avoidance is acceptable, but complete activity restriction is not recommended. No weight-bearing precautions are required for this condition.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of Pellegrini-Stieda disease requires a coordinated interprofessional approach to ensure timely diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and optimal patient outcomes. Early radiographic identification, often preceding symptom onset, depends on effective communication between radiologists and orthopedic specialists. Primary care providers, including general practitioners and advanced practitioners, play a critical role in recognizing clinical presentations and initiating appropriate imaging and referrals. Misdiagnosis as MCL sprain, osteoarthritis, or meniscal pathology is common without thorough clinical evaluation and imaging.

Once diagnosed, collaboration among physiatrists, physical therapists, nurses, and pharmacists is essential. Physical therapists implement structured ROM and strengthening exercises, while nurses ensure continuity between clinical and rehabilitative care. Pharmacists contribute by managing NSAIDs, corticosteroids, or adjunct therapies. For refractory cases, orthopedic surgeons evaluate the need for surgical excision or reconstruction. Shared decision-making and clear communication across the team enhance patient-centered care, reduce unnecessary interventions, promote safety, and improve functional recovery and satisfaction with care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Medial Collateral Ligament Calcification. This anteroposterior knee radiograph shows linear calcification adjacent to the medial femoral condyle. The ossification corresponds to chronic calcific changes within the medial collateral ligament. The joint spaces are preserved without signs of acute fracture.

Image courtesy S Bhimji MD

References

Porro A, Lorusso L. Augusto Pellegrini (1877-1958): contributions to surgery and prosthetic orthopaedics. Journal of medical biography. 2007 May:15(2):68-74 [PubMed PMID: 17551603]

Somford MP, Janssen RPA, Meijer D, Roeling TAP, Brown C Jr, Eygendaal D. The Pellegrini-Stieda Lesion of the Knee: An Anatomical and Radiological Review. The journal of knee surgery. 2019 Jul:32(7):637-641. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1666867. Epub 2018 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 29991078]

Fakih O, Leriche T, Verhoeven F, Prati C, Wendling D. Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome. Joint bone spine. 2024 Mar:91(2):105660. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2023.105660. Epub 2023 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 37977525]

Jiménez-Herranz E, de Castro Fernandes JV, Ramos-Álvarez JJ, Del-Castillo-Díez F, Pedrinelli A, Alvariza-Ciancio S, Solís-Mencía C, Del-Castillo-González F. Calcifications of the Knee's Medial Compartment: A Case Report and Literature Review on the Adductor Magnus Tendon as an Uncommon Location and the Role of Ultrasound-Guided Lavage. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2025 Feb 22:15(5):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics15050534. Epub 2025 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 40075782]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYildiz N, Ardic F, Sabir N, Ercidogan O. Pellegrini-Stieda disease in traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2008 Jun:87(6):514. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318174eb1b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18496254]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAltschuler EL, Bryce TN. Images in clinical medicine. Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2006 Jan 5:354(1):e1 [PubMed PMID: 16394294]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePloumis A, Petropoulos O, Balta AΑ, Manolis I, Vasileiadis GΙ, Varvarousis DΝ. Pellegrini-Stieda Disease in a Severely Injured Patient with Spinal Cord Injury. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions. 2023 Sep 1:23(3):365-367 [PubMed PMID: 37654222]

McArthur TA, Pitt MJ, Garth WP Jr, Narducci CA Jr. Pellegrini-Stieda ossification can also involve the posterior attachment of the MPFL. Clinical imaging. 2016 Sep-Oct:40(5):1014-7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2016.06.001. Epub 2016 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 27348056]

Scheib JS, Quinet RJ. Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome mimicking acute septic arthritis. Southern medical journal. 1989 Jan:82(1):90-1 [PubMed PMID: 2911769]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceda Paz AC, Carod Artal FJ, Kalil RK. The function of proprioceptors in bone organization: a possible explanation for neurogenic heterotopic ossification in patients with neurological damage. Medical hypotheses. 2007:68(1):67-73 [PubMed PMID: 16919892]

Mendes LF, Pretterklieber ML, Cho JH, Garcia GM, Resnick DL, Chung CB. Pellegrini-Stieda disease: a heterogeneous disorder not synonymous with ossification/calcification of the tibial collateral ligament-anatomic and imaging investigation. Skeletal radiology. 2006 Dec:35(12):916-22 [PubMed PMID: 16988801]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNiitsu M, Ikeda K, Iijima T, Ochiai N, Noguchi M, Itai Y. MR imaging of Pellegrini-Stieda disease. Radiation medicine. 1999 Nov-Dec:17(6):405-9 [PubMed PMID: 10646975]

Theivendran K, Lever CJ, Hart WJ. Good result after surgical treatment of Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2009 Oct:17(10):1231-3. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0725-0. Epub 2009 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 19221717]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRizky DA, Lee K, Sulaeman WS, Butarbutar JCP, Suginawan ET. Ultrasound-guided Percutaneous Lavage as Treatment for Pellegrini-Stieda Syndrome with Suspected Same Patho-mechanism as Rotator Cuff Syndrome: A Case Report. Journal of orthopaedic case reports. 2023 Jul:13(7):27-32. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2023.v13.i07.3742. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37521393]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGreidanus BD. A Novel Treatment of Painful Medial Collateral Ligament Calcification (Pellegrini-Stieda Syndrome): A Case Report. Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine. 2022 Jul 1:32(4):e441-e442. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000982. Epub 2021 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 34759184]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBhavani P, Dwidmuthe S, Math SAB, Das D, Roy M, Reddy MHV. Breaking Free from Knee Pain: A Surgical Triumph in Managing Pellegrini-Stieda Syndrome with Massive Lesion: A Case Report. Journal of orthopaedic case reports. 2024 Apr:14(4):13-17. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2024.v14.i04.4342. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38681929]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang Q, Guo W, Shi Z, Wang W, Zhang Q. Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty for Knee Osteoarthritis With the Pellegrini-Stieda Lesion: A Case Report. Frontiers in surgery. 2022:9():922896. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.922896. Epub 2022 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 35874137]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFernández-Cuadros ME, Albaladejo-Florín MJ, Álava-Rabasa S, Pérez-Moro OS. [Calcification of the medial collateral ligament of the knee: Rehabilitative management with radial electro shock wave therapy plus iontophoresis of a rare entity. Clinical case and review]. Rehabilitacion. 2022 Oct-Dec:56(4):388-394. doi: 10.1016/j.rh.2021.06.001. Epub 2021 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 34238612]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence