Introduction

Parotitis, the most common inflammatory condition affecting the major salivary glands, refers to swelling or inflammation of the parotid glands and may present as a localized issue or a manifestation of a systemic illness. This condition arises from various causes, including infections, ductal obstruction, autoimmune or metabolic diseases, medications, and structural abnormalities. Clinically, parotitis is typically painful and presents with unilateral glandular swelling and reduced salivary flow, except in cases associated with HIV, metabolic causes, and some salivary gland tumors. Additional symptoms may include fever, chills, headache, sore throat, fatigue, and loss of appetite.

Viral or bacterial infections are typically the primary cause of acute parotitis. Common viral pathogens include mumps, influenza, parainfluenza, coxsackievirus, echovirus, and HIV. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species are the most common bacterial causes.[1] Additional causes of acute parotitis are mechanical obstruction from salivary stones or ductal strictures, external beam radiation, contrast exposure, and radioiodine treatment. Chronic parotitis often results from recurrent infections; autoimmune conditions, such as Sjögren disease or sarcoidosis; tumors; and metabolic disorders, such as diabetes mellitus. Additional risk factors include tuberculosis, inflammatory disorders, dehydration, malnutrition, immunosuppression, and medications that reduce salivary flow. Although uncommon, complications may include facial nerve palsy, sepsis, Lemierre syndrome, osteomyelitis, and multiorgan failure.

Diagnosis is primarily clinical but supported by imaging, with ultrasound commonly used to confirm glandular inflammation and detect underlying issues such as stones, abscesses, or tumors. Additional imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is necessary in suspected cases of malignancy or sialolithiasis. Gram stain and culture of purulent material, obtained by gland massage or ultrasound-guided aspiration, can guide antibiotic selection.[2] Laboratory testing is generally unnecessary and reserved for patients with likely underlying autoimmune disorders. Treatment is guided by the underlying etiology. Suppurative parotitis warrants hospitalization and intravenous (IV) antibiotics due to the risk of deep tissue involvement. Supportive care may include warm compresses; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; sialogogues, such as pilocarpine to stimulate salivary flow; and sialendoscopy to clear ductal debris.[3] In cases that are chronic or refractory, parotidectomy may be necessary.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

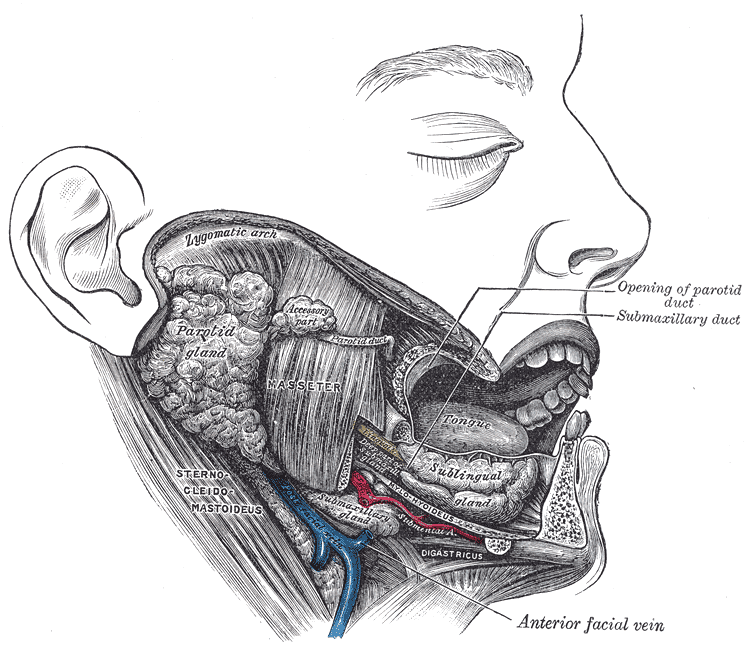

The parotid glands, located anterior to the external auditory canal, are divided into superficial and deep lobes by the facial nerve (see Image. Lateral View of the Salivary Glands). The Stensen duct drains saliva into the mouth opposite the upper second molar. Obstruction of this duct increases the risk of parotitis, which may be acute or chronic and result from infections, obstruction, inflammation, systemic conditions, or a combination of these factors.

Infectious Causes

Bacterial parotitis typically presents with sudden, painful swelling of the gland and often occurs in the setting of salivary stasis resulting from dehydration, ductal obstruction, or poor oral hygiene. S aureus is the most common cause, along with oral aerobic and anaerobic flora. Klebsiella spp are common in patients with diabetes mellitus from Southeast Asia. At the same time, Haemophilus influenzae may also contribute to community-acquired cases.[4] Hospitalized patients are at risk for infections with Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Less common pathogens include mycobacterial infections and Actinomyces species.[5] Tuberculosis-related parotitis is rare but may coexist with pulmonary tuberculosis in up to 25% of cases.[6] Burkholderia pseudomallei, the cause of melioidosis, is another potential pathogen, particularly in endemic regions.

Viral causes of parotitis include mumps—the most common—HIV, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, influenza, parainfluenza, coxsackievirus, and, more recently, SARS-CoV-2.[7] Benign lymphoepithelial cysts within the salivary glands, most often the parotid glands, are the primary cause of parotid swelling in patients with HIV.[8]

Obstructive Causes

Mechanical obstruction of salivary flow is a common cause of parotid gland swelling and may result from sialolithiasis, ductal strictures, or, less commonly, foreign bodies lodged within the duct. Obstruction often leads to intermittent gland enlargement, particularly during meals or when stimulated by salivation. Pneumoparotitis, another form of obstructive parotitis, occurs when air is forced retrograde into the duct, such as with positive-pressure ventilation or activities such as playing wind instruments. External compression from dentures or adjacent anatomical structures can also hinder salivary drainage. Mechanical obstruction is considered a leading cause of chronic sialadenitis, where repeated inflammation leads to progressive acinar damage, fibrosis, and sialectasis.

Inflammatory and Autoimmune Causes

Non-infectious inflammation can result from external beam radiation, radioiodine therapy, or the use of IV contrast agents. External beam radiation most often causes acute swelling by damaging the gland's parenchyma. Juvenile recurrent parotitis presents as recurrent parotid swelling without clear infection or obstruction. Experts believe that the cause of juvenile recurrent parotitis is multifactorial. However, the primary underlying cause is likely underproduction of saliva.[9] Studies reveal an increased incidence of juvenile recurrent parotitis in children with atopic conditions and obesity, likely due to an overlap between juvenile recurrent parotitis and eosinophilic sialodochitis and pro-inflammatory changes in the salivary glands associated with obesity.[10] Autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren disease, sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus can also lead to chronic parotid inflammation. Patients with Sjögren disease develop parotitis due to stones, strictures, or mucus plugs (see Image. Sjögren-Related Parotid Disease).

Metabolic and Drug-Induced Causes

Sialosis (sialadenosis) is a chronic, painless, non-inflammatory, non-neoplastic enlargement of the salivary glands, often associated with metabolic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, liver disease, alcohol use disorder, and bulimia. Certain medications, such as clozapine, iodinated contrast, L-asparaginase, and anticholinergics, can also induce parotid swelling.

Neoplastic Causes

Both benign and malignant tumors of the parotid gland can present as chronic, painless swelling. Tumors may arise from salivary tissue or represent metastases from other head and neck malignancies. The most common benign neoplasm is a pleomorphic adenoma. Additional benign neoplasms are the Warthin tumor, basal cell adenoma, and canalicular adenoma. The most common malignant neoplasms are mucoepidermoid carcinomas and adenoid cystic carcinomas.[11][12][13]

Additional Causes

Additional uncommon causes of parotitis can include trauma or surgery, such as parotitis caused by manipulation of the gland during a carotid endarterectomy. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, amyloidosis, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, Kimura disease, and Rosai-Dorfman disease, a rare non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis, are all additional uncommon causes of parotitis.[14]

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of parotitis depends on the underlying cause and the specific population affected. Factors that affect epidemiology include vaccination rates, age-related physiological changes, access to health care, and underlying medical conditions. Death from parotitis is related to complications such as respiratory obstruction, septic jugular thrombophlebitis, bacteremia, and osteomyelitis of the adjacent facial bones in patients with acute suppurative parotitis. In the remaining patients, the mortality rate parallels that of the underlying condition.

Infectious Causes

Acute suppurative parotitis is uncommon and disproportionately affects infants younger than 1 and hospitalized older adults who are dehydrated or intubated postoperatively. Studies estimate the incidence to be 0.01% to 0.02% of hospitalized older adults and 0.002% to 0.04% of postoperative patients.[15] Neonatal suppurative parotitis is similarly rare, with one study reporting only 32 cases over a 35-year period.[16][17][18] Any circumstance that diminishes saliva flow through the Stensen duct predisposes patients to acute bacterial parotitis. Common factors include anticholinergic medications, salivary gland stones, malnutrition, and oral malignancies. Additional potential risk factors for neonates and infants include low birth weight, dehydration, immune suppression, ductal obstruction, oral trauma, and structural abnormalities of the parotid gland.[18]

Approximately 1% to 10% of patients with HIV develop salivary gland enlargement, a more common finding in children than adults. Tuberculous parotitis accounts for 2.5% to 10% of parotid pathologies.[8][19]

Mumps occurs most often in school- and college-aged patients, with parotitis most common in children aged 2 to 9. The annual incidence of mumps in the United States fluctuates from year to year. The United States Centers for Disease Control reported 6369 cases of mumps in 2016 and 5629 in 2017, followed by a steady decline to fewer than 500 cases per year beginning in 2021.

Melioidosis primarily affects individuals in Thailand, Singapore, northern Australia, and Malaysia. Parotitis is a common presenting feature in children, especially in Thailand and Cambodia, and accounts for 40% of cases in these areas. The higher incidence of parotitis in these areas is likely due to ingestion of water contaminated with B pseudomallei.[20]

Obstructive Causes

Nearly 50% of benign salivary gland disorders are due to stones or strictures in the salivary gland ducts.[21] Approximately 80% of stones occur in the submandibular glands, 6% to 20% affect the parotid glands, and 1% to 2% affect the sublingual glands.[22]

Inflammatory and Autoimmune Causes

Historically, juvenile recurrent parotitis has been the second most common cause of parotitis in children, following mumps as the most common cause.[9] Given the decreased rate of mumps, juvenile recurrent parotitis may now be the most common cause of parotitis in children in countries with high vaccination rates. Juvenile recurrent parotitis affects males more than females and most commonly occurs between the ages of 4 months and 15 years, with spontaneous remission at puberty.[23] A recent retrospective review found that the highest incidence of juvenile recurrent parotitis occurs in Black males between the ages of 2 and 8.[10] Additionally, studies suggest that infants born preterm and small for gestational age, particularly those born to younger mothers from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, may have an increased risk of developing juvenile recurrent parotitis.[24]

Chronic parotitis most commonly affects adults between the ages of 40 and 60. Unless otherwise mentioned, parotitis itself occurs equally in men and women and across all races. However, parotitis associated with a systemic illness mimics the demographics associated with the underlying illness. Rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus affect women more than men. Rheumatoid arthritis has a worldwide prevalence of 0.21%. The prevalence in the United States and northern Europe is between 0.5% and 1%. In the United States, systemic lupus erythematosus is most prevalent in females who are American Indian and Alaskan Native, followed by females who are Black.[25] Unlike adults who more frequently present with dry eyes and a dry mouth, parotitis is a dominant presenting feature in children with Sjögren disease.[26]

Metabolic and Drug-Induced Causes

Sialosis occurs most commonly in patients aged 30 to 70, and 50% of cases are associated with diabetes mellitus, alcohol use disorder, liver disease, metabolic syndrome, bulimia, and malnutrition.[27]

Neoplastic Causes

Salivary gland tumors account for 6% to 8% of all head and neck tumors in the United States, corresponding to an incidence of 2 to 8 per 100,000 individuals in the United States. According to the World Health Organization, nearly 80% to 85% of these tumors occur in the parotid glands.[28] Approximately 75% of parotid tumors are benign, whereas the remaining 25% are malignant.[29][30] Pleomorphic adenomas represent approximately 50% of all benign parotid tumors. In comparison, mucoepidermoid and adenoid cystic carcinomas account for approximately 50% of malignant parotid tumors. Risk factors for developing salivary gland tumors include a history of radiation exposure; smoking, specifically related to Warthin tumors; infections, such as Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, and human papillomavirus (HPV); and industrial exposures to substances, such as rubber, nickel compounds, and chemicals used in beauty salons.[28] Warthin tumors primarily occur in males.

Pathophysiology

As an exocrine gland, the parotid gland secretes saliva into the oral cavity in response to parasympathetic stimulation. Saliva plays a vital role in chewing, swallowing, digestion, and speech, and contains electrolytes, mucin, and enzymes such as amylase. The pathophysiology of parotitis is dependent on the underlying cause.

Infectious Causes

The primary mechanism of suppurative parotitis is retrograde infection, where oral bacteria travel up the Stensen duct into the parotid gland. Typically, a valve within the duct maintains a one-way flow of saliva from the gland to the oral cavity, helping to prevent the entry of bacteria. However, this valve may occasionally become incompetent, leading to an ascending bacterial infection involving mixed oral flora. Reduced salivary flow creates an environment conducive to bacterial growth, thereby increasing the risk of parotitis. Impaired saliva clearance allows bacteria to ascend the ductal system or become trapped behind an obstruction, leading to acute suppurative parotitis. The infection triggers an inflammatory response in the parotid gland, resulting in swelling, pain, and tenderness. In more severe cases, abscesses may form within or around the gland as a direct extension of parotitis or through hematogenous spread to intraparotid or periparotid lymph nodes.[31]

Benign lymphoepithelial cysts are a characteristic feature of parotitis associated with HIV. Experts suspect 2 potential causes of benign lymphoepithelial cysts. The first proposed mechanism involves the migration of infected CD4+ T cells into the parotid glands, triggering lymphoid hyperplasia and ductal metaplasia. This abnormal cellular proliferation may obstruct the salivary ducts, leading to ductal dilation and the formation of cysts within the gland. In the second proposed mechanism, HIV-related reactive lymphoproliferation occurs in the parotid lymph nodes, causing the parotid glandular epithelium to become entrapped within the lymph nodes, resulting in cystic enlargement.

Mumps parotitis arises from the mumps virus directly infecting the parotid glands. The virus spreads through respiratory droplets, direct contact, and fomites and replicates in the nasopharynx and regional lymph nodes. The virus then enters the bloodstream and eventually reaches the salivary glands.

Obstructive Causes

The exact cause of sialolithiasis is unknown. Key contributing factors include stagnant salivary flow, elevated salivary calcium levels, and injury or inflammation of the duct. A foreign object or bacteria often acts as a nidus for sialolith formation. Most salivary stones consist of calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite. Although less common in the parotid than in the submandibular glands due to the production of serous rather than mucoid saliva, sialolithiasis is a common condition where calculi formed from inorganic crystals can obstruct the gland duct.

Inflammatory and Autoimmune Causes

A viral infection may trigger the initial insult that leads to autoimmune parotitis. Epithelial cells of the parotid gland take up autoantigens or viral antigens bound in antigen-antibody complexes. These complexes interact with class II histocompatibility molecules in the cytoplasm, prompting the expression of the human leukocyte antigen complex on the cell surface for presentation to T cells. CD4+ cells recognize antigens on the cell surface and release cytokines, thereby triggering additional T-cell activation. Subsequently, B cells enter the gland and secrete autoantibodies, such as anti-Sjögren syndrome type A antigen (anti-SSA), anti-Sjögren syndrome type B antigen (anti-SSB), and rheumatoid factor, resulting in oligoclonal expansion and acinar destruction that can increase the risk of neoplastic transformation.[32]

The pathogenesis of juvenile recurrent parotitis is multifactorial. Research suggests a genetic predisposition in some children and adolescents, along with congenital anomalies of the parotid gland or duct, and links to autoimmune conditions. Viral or bacterial infections may initiate or exacerbate glandular inflammation. Reduced salivary production and impaired ductal outflow increase susceptibility to ascending infections of the salivary glands in individuals affected by this condition.

Metabolic and Drug-Induced Causes

The exact pathophysiology of sialosis remains unclear, but researchers believe the changes result from impaired autonomic regulation of the parotid glands. This dysfunction leads to acinar cell enlargement and the accumulation of zymogen granules—specialized organelles in the pancreas and salivary glands that store digestive enzymes.[33] Similarly, the mechanism underlying drug-induced parotitis is not fully understood. However, likely possibilities are smooth muscle spasms, anticholinergic effects, and altered autonomic effects. Additionally, the accumulation of iodine in the salivary gland ducts may trigger an inflammatory response, resulting in swelling or inflammation of the parotid gland.

Neoplastic Causes

The uncontrolled growth of cells in the parotid gland is the primary pathophysiology of parotitis due to a neoplastic process. The exact pathophysiology of Warthin tumors is unknown. Some hypotheses include DNA damage, mitochondrial metabolic dysfunction, aging cells, senescence-associated secretory phenotype, HPV, and immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4). Cells that are subject to excessive extracellular and intracellular stress become senescent by being locked into cell-cycle arrest, which prevents them from passing on cellular damage to the next generation of cells and thereby prevents malignant transformation. Senescent cells are found primarily in renewable tissues and in tissues that experience prolonged inflammation. Some senescent cells can transform and develop senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Senescence-associated secretory phenotype cells secrete pro-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic interleukins (ILs), inflammatory cytokines, and growth factors, such as IL-6, IL-1, IL-8 (CXCL-8), growth-regulated oncogene α (GROα or CXCL-1), and growth-regulated oncogene β (GROβ or CXCL-2) that can affect surrounding cells.

History and Physical

On physical examination, a normal parotid gland is soft, smooth, non-tender, and generally not palpable. Gentle compression typically produces clear saliva.

Infectious Causes

The clinical presentation of infectious parotitis varies depending on the underlying cause and patient population. Acute bacterial parotitis typically presents with unilateral, progressively painful glandular swelling, often accompanied by overlying erythema, pain with chewing, and difficulty opening the mouth. Systemic symptoms, such as fever and chills, are common, and clinicians can express purulent discharge from the Stensen duct in approximately 50% of cases. In neonates, however, the presentation may be more subtle, with fussiness and preauricular erythema often reported in the absence of fever.

Viral parotitis, particularly caused by the mumps virus, typically begins with fever, headache, malaise, and myalgia, followed by swelling of the parotid glands within 48 hours.[34] The swelling is often initially unilateral but becomes bilateral in approximately 90% of cases.[35] Other viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, parvovirus, and human herpesvirus 6, can cause similar symptoms. Additionally, cases of viral parotitis are not typically associated with purulent drainage from the Stensen duct. HIV-associated parotitis, especially in the context of benign lymphoepithelial cysts, presents as chronic, bilateral, painless glandular swelling, typically without accompanying dry mouth.[36]

Most adult patients with melioidosis are asymptomatic or have subclinical disease; patients who are symptomatic most commonly present with pneumonia. However, infection can present in the skin, soft tissue, and genitourinary tract, with nearly 50% experiencing bacteremia and 25% presenting with septic shock. Parotitis is a common presenting feature in children.

Tuberculous parotitis typically presents as a slow-growing, non-tender, unilateral swelling. Although uncommon, affected individuals may also exhibit systemic signs of tuberculosis, including weight loss, fever, night sweats, chest pain, cervical lymphadenopathy, and hemoptysis.[37]

Obstructive Causes

Obstructive causes of parotitis, such as sialolithiasis, typically present with intermittent, painful gland swelling, often triggered by eating, when saliva flow increases but cannot drain due to blockage. However, presentations can vary—about one-third of patients may have painless swelling, and around 10% may experience pain without visible swelling. A stone may be palpable within the Stensen duct or visible at the ductal opening. Signs of secondary infection include worsening pain, fever, and erythema overlying the affected area.

Inflammatory and Autoimmune Causes

Inflammatory and autoimmune causes of parotitis encompass a range of conditions, each with distinct clinical characteristics. In Sjögren disease, patients may experience chronic or intermittent enlargement of the salivary glands, most commonly affecting the parotid glands, although the submandibular glands can also be involved. The glands are typically firm and non-tender, with swelling that may be unilateral or bilateral. Associated symptoms often include dry eyes, described as a gritty sensation, and dry mouth, which may lead to difficulty swallowing, problems wearing dentures, trouble eating dry foods, and an inability to speak for extended periods. Physical examination may reveal dry lips, poor dentition, recurrent oral candidiasis, and a lack of saliva pooling beneath the tongue.

Juvenile recurrent parotitis presents with intermittent, recurrent, painful swelling of one or both parotid glands, often accompanied by erythema overlying the affected area and fever. Episodes generally last 24 to 48 hours but can persist for up to 2 weeks. Patients with bulimia nervosa also experience chronic parotid gland enlargement. Interestingly, cessation of purging may trigger an acute episode of sialadenosis, resulting in painful, bilateral parotid swelling.

Radiation-induced parotitis typically presents with acute pain and overlying erythema in the affected gland, accompanied by dry mouth. Although symptoms often resolve over several months due to glandular atrophy from radiation damage, they may recur if salivary function returns and ductal strictures develop.[38]

Metabolic and Drug-Induced Causes

Sialosis presents as chronic, painless, bilateral parotid enlargement that does not fluctuate. Symptoms may also occur in the submandibular glands.

Neoplastic Causes

Salivary gland tumors tend to present as firm, painless masses. Parotid tumors may also affect the facial nerve, leading to signs such as facial asymmetry, inability to raise the eyebrow or close the eye, drooping of the mouth, and loss of definition in the nasolabial fold. Additional symptoms may include impaired taste, reduced tear production, and altered sensation on the affected side. Malignant tumors spread to the intraparotid and cervical lymph nodes first, with distant metastases most often encountered in the lungs, followed by the liver and the bones.[13] Warthin tumors are frequently bilateral.

Evaluation

Infectious Causes

Patients with acute suppurative parotitis require a thorough physical examination, including evaluation for purulent drainage from the Stensen duct, fluctuance over the gland, and potential complications, such as facial nerve involvement, abscess formation, Lemierre syndrome, or fistulas. Clinicians should perform parotid massage from posterior to anterior to express purulent material and send it for Gram stain and culture. Abscesses should be aspirated under ultrasound guidance to obtain samples for microbiologic analysis. A thorough examination of the ears, teeth, and cervical lymph nodes is also essential to identify alternative sources of infection.

Unilateral cystic enlargement should prompt HIV testing, beginning with a combination antigen/antibody immunoassay followed by an HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay if the antigen/antibody screen is positive. Tuberculosis-associated parotitis warrants fine-needle aspiration with cytology, culture, Ziehl-Neelsen stain, and polymerase chain reaction or cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test.[39] A positive result should lead to chest imaging to assess for pulmonary tuberculosis, as CT, MRI, and ultrasound are not diagnostic for tuberculosis-related cases.

Obstructive Causes

The diagnosis of salivary gland stones is primarily clinical, based on a history of painful gland swelling during meals or when anticipating food, and confirmed by palpation or direct visualization of a stone at the duct opening. Imaging is useful when the diagnosis is uncertain or when a tumor is suspected. A high-resolution noncontrast CT scan is the preferred imaging modality, offering excellent sensitivity for detecting stones. Ultrasound is a valuable alternative, capable of identifying 90% of stones larger than 2 mm, although it is limited in detecting tumors and ductal strictures.[40] Magnetic resonance sialography is a noninvasive alternative to conventional sialography and may aid in evaluating ductal abnormalities or planning surgical interventions.[41][42][43]

Inflammatory and Autoimmune Causes

Clinicians establish the diagnosis of juvenile recurrent parotitis based on a patient's history and physical examination, following laboratory evaluation to exclude other possible causes, such as mumps, Sjögren disease, celiac disease, and sarcoidosis.[44] Recommended laboratory tests include angiotensin-converting enzyme levels, anti-Sjögren's syndrome A (anti-Ro/SSA) and anti-Sjögren's syndrome B (anti-La/SSB) antibodies, tissue transglutaminase-IgA, and serum IgA levels, all of which should be normal.[44] Patients with an IgA deficiency should have a deamidated gliadin peptide-IgG test to screen for celiac disease. A small bowel biopsy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of celiac disease in patients with positive serology or negative serology but a high probability of celiac disease. Ultrasound of the parotid gland can aid in the diagnosis of juvenile recurrent parotitis. Results reveal heterogeneous glandular tissue and nodular hypoechoic areas.

According to the American Academy of Rheumatology, the diagnosis of primary Sjögren disease is based on a scoring system that incorporates 5 weighted clinical and laboratory criteria. The presence of anti-SSA antibodies and focal lymphocytic sialadenitis on labial salivary gland biopsy each contributes 3 points. Clinicians consider a biopsy positive if it shows a focus score of 1 or more lymphocytic foci per 4 mm² of glandular tissue. Additional findings, each contributing 1 point, include an ocular staining score of 5 or higher (or a van Bijsterveld score of 4 or greater), a Schirmer's test result of 5 mm or less in 5 minutes, and an unstimulated salivary flow rate of 0.1 mL/min or less. A total score of 4 or more confirms the classification of primary Sjögren disease.

Metabolic and Drug-Induced Causes

Clinicians should suspect sialosis based on the patient's history and physical examination. Ultrasound reveals diffuse enlargement and increased hyperechoic and homogeneous echotexture.[45] Patients with characteristic risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, alcohol use disorder, metabolic syndrome, bulimia, malnutrition, or liver disease, along with characteristic ultrasound findings, require no further evaluation.

Neoplastic Causes

Evaluation of a suspected parotid neoplasm begins with a detailed history and a thorough physical examination. Clinicians should inquire about the duration and growth rate of the mass, associated pain, signs of facial nerve involvement, and any personal history of skin cancer, particularly melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma of the face or scalp. The physical examination should assess the size and mobility of the mass, its relationship to surrounding structures, facial nerve function, skin changes suggestive of malignancy, and any intraoral involvement.

Imaging plays a crucial role in characterizing lesions, determining their location, evaluating for local invasion or metastasis, and distinguishing between benign and malignant processes. Ultrasound is an acceptable initial imaging method for assessing superficial parotid lobe lesions. At the same time, CT or MRI is necessary for deep lobe involvement or if malignancy is suspected or confirmed on biopsy.[46] Definitive diagnosis requires tissue sampling, typically through fine-needle aspiration or ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy, to determine whether the mass is benign or malignant.

Treatment / Management

Infectious Causes

Due to the risk of infection spreading to the deep tissues of the head and neck, initial management of acute suppurative parotitis typically requires inpatient care. Treatment includes IV hydration; antibiotics; stimulation of salivary flow by application of warm compresses; administration of sialagogues, such as lemon drops; salivary gland massage; oral hygiene; and appropriate analgesics.[47] If there is no clinical improvement within 48 hours, repeat imaging and cultures should be performed, and broader-spectrum antibiotics should be considered. In immunocompetent adult patients with a community-acquired infection, the antibiotic choice should provide coverage for S aureus, H influenzae, viridans, other streptococci, and oral anaerobes. First-line therapy is as follows:

- Ampicillin-sulbactam or

- Cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, or levofloxacin plus metronidazole or clindamycin

Clinicians should add vancomycin, linezolid, or daptomycin in patients colonized with methicillin-resistant S aureus or who are at risk for methicillin-resistant S aureus.[48] Clinicians should reserve fluoroquinolones, such as levofloxacin, for patients who are unable to tolerate or have a contraindication to alternative therapies.

Immunocompromised adults or those who have experienced health care–associated infections should also have antimicrobial coverage for methicillin-resistant S aureus, Enterobacterales, and P aeruginosa. Therapy begins with vancomycin, linezolid, or daptomycin plus one of the following:

- Cefepime plus metronidazole or

- Piperacillin-tazobactam or

- Imipenem or

- Meropenem

For uncomplicated cases, the typical duration of therapy is 10 to 14 days. Once patients have clinically improved, they can transition to oral therapy. Appropriate oral therapy depends on culture results if obtained; however, continued coverage for oral flora remains warranted regardless of the culture results. Suggested oral therapies for community-acquired infections include amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefuroxime plus metronidazole, levofloxacin plus metronidazole, and moxifloxacin. For immunocompromised patients or those with health care-related infections, experts recommend a combination of levofloxacin and metronidazole. Alternatively, if methicillin-resistant S aureus coverage is necessary, clindamycin plus ciprofloxacin, linezolid plus ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole plus ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole may be considered.

Neonates with parotitis generally receive a first-generation cephalosporin in combination with an aminoglycoside or a third-generation cephalosporin.[49]

Parotitis due to HIV and tuberculosis responds well to treatment of the underlying illness. Additional therapeutic options for HIV-related parotitis are a partial parotidectomy or radiation therapy.[50][51][52] Patients with a parotid abscess require drainage.

Obstructive Causes

Conservative management is the cornerstone of sialolithiasis. Clinicians should instruct patients to stay well-hydrated, massage the duct of the gland, apply warm compresses, discontinue anticholinergic medications if possible, and increase salivary flow by sucking on tart candies, such as lemon drops. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are appropriate analgesics and help decrease inflammation, although patients with severe pain may require opioids. Patients with a suspected secondary infection should receive dicloxacillin or cephalexin. Patients who fail conservative management can undergo sialoendoscopy to facilitate stone removal using forceps and a wire basket. If a stone is larger than 4 mm, clinicians can combine sialoendoscopy with laser-assisted lithotripsy.

Additionally, some settings offer extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy for intraductal stones greater than 7 mm. However, this is not an approved indication by the United States Food and Drug Administration.[53][54] Transoral surgical removal of parotid stones is generally not possible unless they are near the opening of the Stensen duct. Parotidectomy is a treatment modality of last resort when affected patients fail all other conservative measures.

Inflammatory and Autoimmune Causes

Initial management of juvenile recurrent parotitis and Sjögren disease includes conservative measures. No consensus exists on the appropriate management of juvenile recurrent parotitis. Some clinicians use antibiotics, such as clindamycin, for acute episodes. However, experts question their role. A single-day course of oral steroids is an additional therapeutic option.[44] Sialendoscopy is also helpful for treatment. Clinicians can perform an intraductal lavage with saline, hydrocortisone, or antibiotics and dilate strictures.[55](B2)

In patients with parotitis related to Sjögren disease, clinicians may prescribe antibiotics if secondary bacterial infection is suspected. A short course of oral corticosteroids, tapered over 2 weeks, can provide rapid relief of pain and swelling. For recurrent episodes linked to ductal obstruction, secretagogues such as pilocarpine and regular duct massage may help prevent recurrence.[56] Sialoendoscopy is also effective in managing chronic or recurrent inflammation. Systemic therapies, such as methotrexate or hydroxychloroquine, are considered for patients with systemic symptoms, pain, or cosmetic concerns. Clinicians may suggest rituximab in more severe cases. Persistent symptoms beyond 8 weeks warrant evaluation for non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma with imaging and tissue biopsy.(B2)

Metabolic and Drug-Induced Causes

The primary management of sialosis due to metabolic causes involves treating the underlying cause. However, this does not guarantee complete resolution of parotid swelling. Additional treatment options include oral pilocarpine drops, botulinum toxin injection, insufflation of steroids through the Stensen duct, and, in rare cases, parotidectomy.[57]

Neoplastic Causes

Surgical resection is the preferred treatment for parotid tumors. The extent of surgery depends on whether the tumor is benign or malignant, its size, location within the gland, degree of invasiveness, and its relationship to the facial nerve. Patients who are at risk for locoregional recurrence often receive adjuvant radiation therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for parotid gland swelling include the following:

- Salivary gland stone

- Salivary gland stricture

- Ductal foreign body

- Pneumoparotitis

- External compression of the Stensen duct from dentures or a hypertrophied masseter muscle

- Bacterial sialadenitis

- Post-radiation sialadenitis

- Viral sialadenitis

- Juvenile recurrent parotitis

- Sialadenitis due to radioiodine therapy and iodinated contrast dye

- Drug-induced sialadenitis

- Bulimia nervosa

- Melioidosis

- Tumors

- Sclerosing polycystic adenosis

- Sialosis due to metabolic causes

- Sjögren disease

- IgG4-related sialadenitis

- Kussmaul disease

- Sarcoidosis

- Granulomatosis with polyangitis

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- HIV

- Amyloidosis

- Metastatic disease to the parotid gland lymph nodes

- Rosai-Dorfman disease

- Masseter hypertrophy

- Branchial cleft cyst

- Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome

- Kimura disease [58][59][60][61][62]

Prognosis

The prognosis for parotitis is generally favorable, especially when treated promptly. Most cases resolve within 7 to 10 days, and full recovery without complications is common. The prognosis becomes less favorable if an abscess or extra-glandular extension occurs. Deep neck space infections increase life-threatening complications such as respiratory compromise and septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein.[63]

For certain conditions, such as juvenile recurrent parotitis, treatments like sialoendoscopy and ductal lavage are often effective in reducing recurrence and alleviating symptoms. The prognosis of parotitis associated with autoimmune disorders typically reflects the course of the underlying disease. Overall survival rates for salivary gland malignancies range from 65% to 75%, although specific outcomes vary depending on tumor type, lymph node involvement, distant metastasis, and facial nerve involvement. Facial nerve involvement at the time of diagnosis is associated with a worse prognosis.[64]

Complications

Complications of Parotitis

Complications of parotitis may arise from treatment, an underlying illness, the spread of infection, or the parotitis itself. The following list contains potential complications associated with parotitis:

- Chronic bacterial parotitis

- Lymphoma due to autoimmune parotitis

- Facial paralysis

- Malnutrition

- Lemierre syndrome

- Frey syndrome

- Unmasking of Eagle syndrome, a pharyngeal foreign body sensation, and cervicofacial pain in patients with an elongated styloid process

- Meningoencephalitis, orchitis, oophoritis, pancreatitis, and hearing loss due to mumps

- Fistula formation

- Osteomyelitis

- Death

- Sepsis

- Abscess formation [65][66][67][68][69]

Complications Related to Sialography and Surgical Interventions

- Ductal perforation

- Vascular injury

- Complications related to anesthesia

- Postoperative ductal stenosis

Complications Related to Radiation Therapy

- Xerostomia

- Mucositis

- Dysgeusia

- Poor dentition

- Radiation dermatitis

- Orofacial pain

- Trismus [70]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Parotitis is an inflammation of the parotid glands and may present as either an isolated issue or a manifestation of systemic illness. This condition often causes painful, unilateral glandular swelling and reduced salivary flow, although some forms, such as HIV-related parotitis, may be painless. Viral or bacterial infections typically cause acute parotitis, whereas chronic cases may result from recurrent infections, autoimmune diseases, ductal obstruction, or structural abnormalities.

Clinicians should educate patients on preventive strategies to reduce the risk of parotitis. Key measures include maintaining proper hydration, practicing good oral hygiene, and managing underlying medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus or autoimmune disorders. Patients taking medications that reduce salivary flow, such as anticholinergics or antihistamines, should be informed of their risk and monitored for early symptoms. Sialogogues, such as lemon drops or pilocarpine, may be recommended to stimulate salivary flow, particularly for individuals prone to ductal blockage. Patients with chronic or recurrent symptoms should recognize early warning signs, such as jaw pain or swelling, especially during meals, and know when to seek timely medical attention. Educating patients about potential complications, such as abscess formation, facial nerve involvement, or systemic infection, reinforces the importance of early diagnosis and intervention to prevent serious outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Parotitis, an inflammatory condition affecting the parotid glands, can present acutely or chronically and result from various causes, including viral or bacterial infections, ductal obstruction, autoimmune diseases, metabolic disorders, medications, or systemic illnesses. Patients typically present with painful, unilateral glandular swelling, often worsened by eating, and may have associated symptoms such as fever, malaise, and xerostomia. Diagnosis is primarily clinical, but imaging confirms the diagnosis and evaluates patients for any underlying pathology. Prompt identification and treatment are important to prevent complications such as abscess formation, facial nerve involvement, or systemic infection.

Effective management of parotitis requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach that emphasizes timely diagnosis, individualized treatment, and patient-centered care. Clinicians and advanced practitioners play a critical role in assessing presenting symptoms, identifying the underlying etiology, ordering appropriate diagnostic imaging, and initiating targeted treatment. Nurses support this care by monitoring vital signs, assessing treatment responses, administering medications, educating patients about hydration and oral hygiene, and identifying signs of worsening infections or complications.

Pharmacists play a crucial role in selecting appropriate antibiotics based on culture results, reviewing potential drug interactions, and counseling patients on medication adherence and possible adverse effects. Radiologists and imaging technicians facilitate accurate diagnosis by performing and interpreting ultrasound, CT, or MRI to assess for ductal stones, abscesses, or suspected tumors. In cases requiring surgical intervention, such as abscess drainage, sialoendoscopy, or parotidectomy, collaboration with otolaryngologists and surgical teams is essential. Regular team communication, including shared documentation and case discussions, enhances continuity of care and prevents fragmentation. This collaborative approach supports early intervention, minimizes complications, and improves outcomes, especially in complex cases such as recurrent or suppurative parotitis. Ultimately, fostering strong interprofessional teamwork improves clinical efficiency, strengthens patient trust, and ensures comprehensive, high-quality care across all stages of parotitis management.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Lateral View of the Salivary Glands. The image shows the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands in relation to surrounding structures. The Stensen duct of the parotid gland and the submandibular duct are visible, opening into the oral cavity. Neighboring muscles, vessels, and bony landmarks provide spatial orientation.

Henry Van Dyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Raad II, Sabbagh MF, Caranasos GJ. Acute bacterial sialadenitis: a study of 29 cases and review. Reviews of infectious diseases. 1990 Jul-Aug:12(4):591-601 [PubMed PMID: 2385766]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSaibene AM, Allevi F, Ayad T, Lechien JR, Mayo-Yáñez M, Piersiala K, Chiesa-Estomba CM. Treatment for parotid abscess: a systematic review. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2022 Apr:42(2):106-115. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-N1837. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35612503]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAndueza Guembe M, Chiesa Estomba CM, Saga Gutiérrez C, Thomas Arrizabalaga I, Ábrego Olano M, Vázquez Quintano M, Altuna Mariezcurren X. Utility of sialendoscopy in the management of juvenile recurrent parotitis. Retrospective study. Acta otorrinolaringologica espanola. 2024 Sep-Oct:75(5):304-309. doi: 10.1016/j.otoeng.2024.05.006. Epub 2024 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 39038536]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBukhari AF, Bugshan AS, Papas A, Desai B, Farag AM. Conservative Management of Chronic Suppurative Parotitis in Patients with Sjögren Syndrome: A Case Series. The American journal of case reports. 2021 Mar 19:22():e929553. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.929553. Epub 2021 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 33739960]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMaurya MK, Kumar S, Singh HP, Verma A. Tuberculous parotitis: A series of eight cases and review of literature. National journal of maxillofacial surgery. 2019 Jan-Jun:10(1):118-122. doi: 10.4103/njms.NJMS_34_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31205402]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRamanan R, Yeola M, P N, S A, Uma Maheswaran K. A Case of Primary Tuberculous Parotitis Mimicking Parotid Neoplasm: A Rare Clinical Entity. Cureus. 2024 Apr:16(4):e58217. doi: 10.7759/cureus.58217. Epub 2024 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 38745804]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlmansour I, Alhagri M. MMRdb: Measles, mumps, and rubella viruses database and analysis resource. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 2019 Nov:75():103982. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.103982. Epub 2019 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 31352145]

Sekikawa Y, Hongo I. HIV-associated benign lymphoepithelial cysts of the parotid glands confirmed by HIV-1 p24 antigen immunostaining. BMJ case reports. 2017 Sep 28:2017():. pii: bcr-2017-221869. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-221869. Epub 2017 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 28963391]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTomar RP, Vasudevan R, Kumar M, Gupta DK. Juvenile recurrent parotitis. Medical journal, Armed Forces India. 2014 Jan:70(1):83-4. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2012.08.013. Epub 2012 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 24623953]

Benaim E, Fan T, Dash A, Gillespie MB, McLevy-Bazzanella J. Common Characteristics and Clinical Management Recommendations for Juvenile Recurrent Parotitis: A 10-Year Tertiary Center Experience. OTO open. 2022 Jan-Mar:6(1):2473974X221077874. doi: 10.1177/2473974X221077874. Epub 2022 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 35187385]

Hay AJ, Migliacci J, Karassawa Zanoni D, McGill M, Patel S, Ganly I. Minor salivary gland tumors of the head and neck-Memorial Sloan Kettering experience: Incidence and outcomes by site and histological type. Cancer. 2019 Oct 1:125(19):3354-3366. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32208. Epub 2019 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 31174233]

Dillon PM, Chakraborty S, Moskaluk CA, Joshi PJ, Thomas CY. Adenoid cystic carcinoma: A review of recent advances, molecular targets, and clinical trials. Head & neck. 2016 Apr:38(4):620-7. doi: 10.1002/hed.23925. Epub 2015 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 25487882]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceXiao CC, Zhan KY, White-Gilbertson SJ, Day TA. Predictors of Nodal Metastasis in Parotid Malignancies: A National Cancer Data Base Study of 22,653 Patients. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2016 Jan:154(1):121-30. doi: 10.1177/0194599815607449. Epub 2015 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 26419838]

Panikar N, Agarwal S. Salivary gland manifestations of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: fine-needle aspiration cytology findings. A case report. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2005 Sep:33(3):187-90 [PubMed PMID: 16078253]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBelczak SQ, Cleva RD, Utiyama EM, Cecconello I, Rasslan S, Parreira JG. Acute postsurgical suppurative parotitis: current prevalence at Hospital das Clínicas, São Paulo University Medical School. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo. 2008 Sep-Oct:50(5):303-5 [PubMed PMID: 18949350]

Lampropoulos P, Rizos S, Marinis A. Acute suppurative parotitis: a dreadful complication in elderly surgical patients. Surgical infections. 2012 Aug:13(4):266-9. doi: 10.1089/sur.2011.015. Epub 2012 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 22913804]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSpiegel R, Miron D, Sakran W, Horovitz Y. Acute neonatal suppurative parotitis: case reports and review. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2004 Jan:23(1):76-8 [PubMed PMID: 14743054]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDecembrino L, Ruffinazzi G, Russo F, Manzoni P, Stronati M. Monolateral suppurative parotitis in a neonate and review of literature. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2012 Jul:76(7):930-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.04.003. Epub 2012 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 22575436]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGayathri B, Kalyani R, Manjula K. Primary tuberculous parotitis. Journal of cytology. 2011 Jul:28(3):144-5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.83479. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21897554]

Pagnarith Y, Kumar V, Thaipadungpanit J, Wuthiekanun V, Amornchai P, Sin L, Day NP, Peacock SJ. Emergence of pediatric melioidosis in Siem Reap, Cambodia. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2010 Jun:82(6):1106-12. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20519608]

Kim MJ, Milliren A, Gerold DJ Jr. Salivary Gland Disorders: Rapid Evidence Review. American family physician. 2024 Jun:109(6):550-559 [PubMed PMID: 38905553]

Mandel L. Salivary gland disorders. The Medical clinics of North America. 2014 Nov:98(6):1407-49. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2014.08.008. Epub 2014 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 25443682]

Iro H, Zenk J. Salivary gland diseases in children. GMS current topics in otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery. 2014:13():Doc06. doi: 10.3205/cto000109. Epub 2014 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 25587366]

Resende de Paiva C, Sørensen KK, Schrøder SA, Foghsgaard J, Torp-Pedersen C, Howitz MF. Early life exposures and risk of salivary gland diseases in childhood: A 28-year nationwide cohort study. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2025 Jun:193():112354. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2025.112354. Epub 2025 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 40286465]

Izmirly PM, Parton H, Wang L, McCune WJ, Lim SS, Drenkard C, Ferucci ED, Dall'Era M, Gordon C, Helmick CG, Somers EC. Prevalence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in the United States: Estimates From a Meta-Analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registries. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.). 2021 Jun:73(6):991-996. doi: 10.1002/art.41632. Epub 2021 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 33474834]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceValim V, Secco A, Reis de Oliveira F, Vázquez M, Barbosa Rosa B, Lourenço Macagnani F, Vargas-Bueno KD, Rojas E, Hernández-Delgado A, Catalan-Pellet A, Hernández-Molina G. Parotid gland swelling in primary Sjögren's syndrome: activity and other sialadenosis causes. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2022 Jul 6:61(7):2987-2992. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab816. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34718449]

Kim D, Uy C, Mandel L. Sialosis of unknown origin. The New York state dental journal. 1998 Aug-Sep:64(7):38-40 [PubMed PMID: 9785837]

Guzzo M, Locati LD, Prott FJ, Gatta G, McGurk M, Licitra L. Major and minor salivary gland tumors. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2010 May:74(2):134-48. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.10.004. Epub 2009 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 19939701]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYu G, Peng X, Gao M, Ye P, Ge N, Jia M, Li B, Tang Z, Hu L, Zhang W. [Research progress in diagnosis and treatment of salivary gland tumors]. Beijing da xue xue bao. Yi xue ban = Journal of Peking University. Health sciences. 2025 Feb 18:57(1):1-6 [PubMed PMID: 39856499]

Spiro RH. Salivary neoplasms: overview of a 35-year experience with 2,807 patients. Head & neck surgery. 1986 Jan-Feb:8(3):177-84 [PubMed PMID: 3744850]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKao WK, Chole RA, Ogden MA. Evidence of a microbial etiology for sialoliths. The Laryngoscope. 2020 Jan:130(1):69-74. doi: 10.1002/lary.27860. Epub 2019 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 30861582]

Capaccio P, Canzi P, Gaffuri M, Occhini A, Benazzo M, Ottaviani F, Pignataro L. Modern management of paediatric obstructive salivary disorders: long-term clinical experience. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2017 Apr:37(2):160-167. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-1607. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28516980]

Guggenheimer J, Close JM, Eghtesad B. Sialadenosis in patients with advanced liver disease. Head and neck pathology. 2009 Jun:3(2):100-5. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0113-6. Epub 2009 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 19644542]

Plotkin SA. Mumps: A Pain in the Neck. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2018 May 15:7(2):91-92. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piy038. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29718326]

Hviid A, Rubin S, Mühlemann K. Mumps. Lancet (London, England). 2008 Mar 15:371(9616):932-44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60419-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18342688]

Orlandi MA, Pistorio V, Guerra PA. Ultrasound in sialadenitis. Journal of ultrasound. 2013:16(1):3-9. doi: 10.1007/s40477-013-0002-4. Epub 2013 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 24046793]

Thakur J, Thakur A, Mohindroo N, Mohindroo S, Sharma D. Bilateral parotid tuberculosis. Journal of global infectious diseases. 2011 Jul:3(3):296-9. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.83543. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21887065]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLi X, Yang J, Qu LY, Zheng DN, Xie XY, Liu DG, Yu GY. Diagnosis and Treatment of Radioactive Iodine-Induced Sialadenitis: A 10-Year Endoscopic Experience. The Laryngoscope. 2024 Nov:134(11):4506-4513. doi: 10.1002/lary.31514. Epub 2024 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 38761158]

Benaissa E, Bahalou MH, Safi Y, Bssaibis F, Benlahlou Y, Chadli M, Maleb A, Elouennass M. Primary tuberculosis of the parotid gland: A forgotten diagnosis about a case! Clinical case reports. 2021 May:9(5):e03954. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3954. Epub 2021 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 34026126]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchapher M, Goncalves M, Mantsopoulos K, Iro H, Koch M. Transoral Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Obstructive Salivary Gland Pathologies. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2019 Sep:45(9):2338-2348. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.05.019. Epub 2019 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 31227261]

Wu CB, Xi H, Zhou Q, Zhang LM. The diagnostic value of technetium 99m pertechnetate salivary gland scintigraphy in patients with certain salivary gland diseases. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2015 Mar:73(3):443-50. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.09.013. Epub 2014 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 25530280]

Bertin H, Bonnet R, Le Thuaut A, Huon JF, Corre P, Frampas E, Langlois EM, Chesneau AD. A comparative study of three-dimensional cone-beam CT sialography and MR sialography for the detection of non-tumorous salivary pathologies. BMC oral health. 2023 Jul 8:23(1):463. doi: 10.1186/s12903-023-03159-9. Epub 2023 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 37420227]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTucci FM, Roma R, Bianchi A, De Vincentiis GC, Bianchi PM. Juvenile recurrent parotitis: Diagnostic and therapeutic effectiveness of sialography. Retrospective study on 110 children. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2019 Sep:124():179-184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.06.007. Epub 2019 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 31202035]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSalehzadeh F, Molatefi R, Mardi A, Nahanmoghaddam N. Juvenile idiopathic recurrent parotitis (JIRP) treated with short course steroids, a case series study and one decade follow up for potential autoimmune disorder. Pediatric rheumatology online journal. 2024 Jan 4:22(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12969-023-00946-0. Epub 2024 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 38178123]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBadarinza M, Serban O, Maghear L, Bocsa C, Micu M, Porojan MD, Chis BA, Albu A, Fodor D. Multimodal ultrasound investigation (grey scale, Doppler and 2D-SWE) of salivary and lacrimal glands in healthy people and patients with diabetes mellitus and/or obesity, with or without sialosis. Medical ultrasonography. 2019 Aug 31:21(3):257-264. doi: 10.11152/mu-2164. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31476205]

Lee YY, Wong KT, King AD, Ahuja AT. Imaging of salivary gland tumours. European journal of radiology. 2008 Jun:66(3):419-36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.01.027. Epub 2008 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 18337041]

Brook I. Acute bacterial suppurative parotitis: microbiology and management. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2003 Jan:14(1):37-40 [PubMed PMID: 12544218]

Mayer M, Esser J, Walker SV, Shabli S, Lechner A, Canis M, Klussmann JP, Nachtsheim L, Wolber P. Bi-institutional analysis of microbiological spectrum and therapeutic management of parotid abscesses. Head & face medicine. 2024 Jul 12:20(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s13005-024-00438-w. Epub 2024 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 38997761]

Ichinose M, Matsushima T, Hataya H. Purulent Discharge from Stensen Duct in Neonatal Suppurative Parotitis. The Journal of pediatrics. 2022 Apr:243():230-231. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.12.029. Epub 2021 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 34952006]

Schwarze-Zander C, Draenert R, Lehmann C, Stecher M, Boesecke C, Sammet S, Wasmuth JC, Seybold U, Gillor D, Wieland U, Kümmerle T, Strassburg CP, Mankertz A, Eis-Hübinger AM, Jäger G, Fätkenheuer G, Bogner JR, Rockstroh JK, Vehreschild JJ. Measles, mumps, rubella and VZV: importance of serological testing of vaccine-preventable diseases in young adults living with HIV in Germany. Epidemiology and infection. 2017 Jan:145(2):236-244. doi: 10.1017/S095026881600217X. Epub 2016 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 27780480]

Shivhare P, Shankarnarayan L, Jambunath U, Basavaraju SM. Benign lymphoepithelial cysts of parotid and submandibular glands in a HIV-positive patient. Journal of oral and maxillofacial pathology : JOMFP. 2015 Jan-Apr:19(1):107. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.157213. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26097320]

Mourad WF, Patel S, Young R, Khorsandi AS, Concert C, Shourbaji RA, Ciarrocca K, Bakst RL, Shasha D, Guha C, Garg MK, Hu KS, Kalnicki S, Harrison LB. Management algorithm for HIV-associated parotid lymphoepithelial cysts. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2016 Oct:273(10):3355-62. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-3926-4. Epub 2016 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 26879995]

Koch M, Schapher M, Mantsopoulos K, von Scotti F, Goncalves M, Iro H. Multimodal treatment in difficult sialolithiasis: Role of extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy and intraductal pneumatic lithotripsy. The Laryngoscope. 2018 Oct:128(10):E332-E338. doi: 10.1002/lary.27037. Epub 2017 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 29243260]

Capaccio P, Torretta S, Pignataro L, Koch M. Salivary lithotripsy in the era of sialendoscopy. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2017 Apr:37(2):113-121. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-1600. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28516973]

Berta E, Angel G, Lagarde F, Fonlupt B, Noyelles L, Bettega G. Role of sialendoscopy in juvenile recurrent parotitis (JRP). European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2017 Dec:134(6):405-407. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2017.06.004. Epub 2017 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 28669808]

Wang S, Marchal F, Zou Z, Zhou J, Qi S. Classification and management of chronic sialadenitis of the parotid gland. Journal of oral rehabilitation. 2009 Jan:36(1):2-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2008.01896.x. Epub 2008 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 18976271]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePark KK, Tung RC, de Luzuriaga AR. Painful parotid hypertrophy with bulimia: a report of medical management. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD. 2009 Jun:8(6):577-9 [PubMed PMID: 19537384]

Brooks KG, Thompson DF. A review and assessment of drug-induced parotitis. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2012 Dec:46(12):1688-99. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R228. Epub 2012 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 23249870]

Reddy R, White DR, Gillespie MB. Obstructive parotitis secondary to an acute masseteric bend. ORL; journal for oto-rhino-laryngology and its related specialties. 2012:74(1):12-5. doi: 10.1159/000334246. Epub 2011 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 22156562]

Fragoulis GE, Zampeli E, Moutsopoulos HM. IgG4-related sialadenitis and Sjögren's syndrome. Oral diseases. 2017 Mar:23(2):152-156. doi: 10.1111/odi.12526. Epub 2016 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 27318181]

Flores Robles BJ, Brea Álvarez B, Sanabria Sanchinel AA, Andrus RF, Espinosa Malpartida M, Ramos Giráldez C, Lerma Verdejo A, Merino Argumanez C, Pérez Pimiento JA, Bellas Menéndez C, Villa Alcázar LF, Andréu Sánchez JL, Jiménez Palop M, Godoy Tundidor H, Campos Esteban J, Sanz Sanz J, Barbadillo Mateos C, Isasi Zaragoza CM, Mulero Mendoza JB. Sialodochitis fibrinosa (kussmaul disease) report of 3 cases and literature review. Medicine. 2016 Oct:95(42):e5132. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005132. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27759642]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePerera E, Revington P, Sheffield E. Low grade marginal zone B-cell lymphoma presenting as local amyloidosis in a submandibular salivary gland. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2010 Nov:39(11):1136-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.05.001. Epub 2010 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 20970706]

Vorrasi J, Zinberg G. Concomitant Suppurative Parotitis and Condylar Osteomyelitis. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2017 Mar:75(3):543-549. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.08.043. Epub 2016 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 27717819]

Terhaard C, Lubsen H, Tan B, Merkx T, van der Laan B, Baatenburg de Jong R, Manni H, Knegt P. Facial nerve function in carcinoma of the parotid gland. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2006 Nov:42(16):2744-50 [PubMed PMID: 16950616]

Denny MC, Fotino AD. The Heerfordt-Waldenström syndrome as an initial presentation of sarcoidosis. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2013 Oct:26(4):390-2 [PubMed PMID: 24082416]

Alabraba E, Manu N, Fairclough G, Sutton R. Acute parotitis due to MRSA causing Lemierre's syndrome. Oxford medical case reports. 2018 May:2018(5):omx056. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omx056. Epub 2018 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 29942528]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEllies M, Laskawi R. Diseases of the salivary glands in infants and adolescents. Head & face medicine. 2010 Feb 15:6():1. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-6-1. Epub 2010 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 20156335]

Permpalung N, Suksaranjit P, Chongnarungsin D, Hyman CL. Unveiling the hidden eagle: acute parotitis-induced eagle syndrome. North American journal of medical sciences. 2014 Feb:6(2):102-4. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.127753. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24696832]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan der Lans RJL, Lohuis PJFM, van Gorp JMHH, Quak JJ. Surgical Treatment of Chronic Parotitis. International archives of otorhinolaryngology. 2019 Jan:23(1):83-87. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1667006. Epub 2018 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 30647789]

Hovan AJ, Williams PM, Stevenson-Moore P, Wahlin YB, Ohrn KE, Elting LS, Spijkervet FK, Brennan MT, Dysgeusia Section, Oral Care Study Group, Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/International Society of Oral Oncology (ISOO). A systematic review of dysgeusia induced by cancer therapies. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2010 Aug:18(8):1081-7. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0902-1. Epub 2010 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 20495984]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence