Introduction

HIV is a retrovirus that causes a multisystemic disease called AIDS. On June 5, 1981, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a report in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report detailing cases of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in 5 previously healthy young men in Los Angeles, California. These cases, involving men who have sex with men, were later identified as the first reported instances of AIDS in the United States.[1][2] Ocular manifestations are commonly observed in patients with HIV infection.[3] Opportunistic infections, vascular abnormalities, neoplasms, neuro-ophthalmic conditions, and adverse effects of medications can cause ocular involvement in patients with HIV infection.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

HIV is a retrovirus that replicates in CD4 T lymphocytes.[5] Transmission occurs by exposure to blood and other body fluids.[6] HIV is commonly transmitted through anal or vaginal intercourse or by sharing needles, syringes, or other equipment used for drug injection.[7] The CDC categorizes HIV infections into 3 stages as follows:

- Stage 1 (acute HIV infection): HIV levels are high in the blood, making individuals very contagious. Flu-like symptoms are common.

- Stage 2 (chronic HIV infection, asymptomatic HIV): The virus remains active but may not cause symptoms. Individuals can still transmit HIV. Treatment can prevent progression to stage 3, but without it, this stage can last over a decade.

- Stage 3 (AIDS): The most severe stage, diagnosed when CD4 cell counts drop below 200 or when opportunistic infections occur.[8] Individuals have weakened immune systems and a high viral load. Without treatment, the typical survival time is approximately 3 years.[8]

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies HIV/AIDS in adults and adolescents with confirmed HIV infection into 4 clinical stages as follows:[9][10]

- Clinical stage 1 (asymptomatic): Patients may have persistent painless generalized lymphadenopathy with enlarged nodes >1 cm in 2 or more non-contiguous sites (excluding inguinal) for 3 months or more without a known cause.

- Clinical stage 2 (mild symptoms): The symptoms include moderate unexplained weight loss (<10% of presumed or measured body weight) and herpes zoster.

- Clinical stage 3 (moderate symptoms): The features include unexplained severe weight loss (>10% of presumed or measured body weight) and pulmonary tuberculosis (TB).

- Clinical stage 4 (severe symptoms): The stage includes AIDS-defining illnesses, including:

- HIV wasting syndrome

- Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

- Recurrent severe bacterial pneumonia

- Chronic herpes simplex infection (orolabial, genital, or anorectal of >1 month in duration or visceral at any site)

- Esophageal candidiasis (or candidiasis of trachea, bronchi or lungs)

- Extrapulmonary TB

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection (retinitis or infection of other organs)

- Central nervous system (CNS) toxoplasmosis

- HIV encephalopathy

- Extrapulmonary cryptococcosis, including meningitis

- Disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infection

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- Chronic cryptosporidiosis

- Chronic isosporiasis

- Disseminated mycosis (extrapulmonary histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis)

- Lymphoma (cerebral or B-cell non-Hodgkin)

- Symptomatic HIV-associated nephropathy or cardiomyopathy

- Recurrent septicaemia (including nontyphoidal Salmonella)

- Invasive cervical carcinoma

- Atypical disseminated leishmaniasis [9]

Some studies suggest that an HIV test should be requested if there is atypical, bilateral, treatment-unresponsive ocular toxoplasmosis or suspicion of CMV retinitis.[11]

Table 1. Ocular Manifestations of HIV Infection

| Category | Disorders |

| Orbit |

|

| Eyelids |

|

| Conjunctiva |

|

| Cornea |

|

| Uvea |

|

| Retina |

|

| Choroid |

|

| Neuro-ophthalmic |

|

| Neoplasia |

|

| Immune recovery uveitis |

|

| Adverse drug reactions |

Abbreviation: CMV, cytomegalovirus; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Epidemiology

According to the WHO, globally, 39.9 million (36.1-44.6 million) people were living with HIV at the end of 2023.[14] An estimated 0.6% (0.6%-0.7%) of adults aged 15 to 49 worldwide are living with HIV, although the burden of the epidemic continues to vary considerably between countries and regions.[14] The WHO African Region remains most severely affected, with 1 in every 30 adults (3.4%) living with HIV, and accounting for more than two-thirds of people living with HIV worldwide.[14] In 2023, an estimated 630,000 people died from HIV-related causes, and an estimated 1.3 million people acquired HIV.[14] In 2023, 1.4 million (1.1-1.7 million) children younger than 15 were infected with HIV.[15]

People living with HIV globally develop ocular complications in approximately 70% to 75% of cases, with incidence closely linked to CD4+ T-cell counts and antiretroviral therapy (ART) access.[16][17] HIV retinopathy is the most common ocular finding in patients with HIV infection.[18] In developing countries, 5% to 25% of people living with HIV may experience blindness.[19][20][21][22] Diseases of the retina and choroid are common in patients with HIV infection, and they may cause visual loss. In the pre-highly active ART era, CMV retinitis was the most prevalent sight-threatening ocular infection, affecting 25% to 42% % of patients with AIDS.[23][24][25] For patients who have CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts below 50 cells/μL, the rate of CMV infection was 0.2 cases per person-year.[23][25] However, with the widespread availability of HAART, the incidence of CMV retinitis has declined significantly to around 5.6 cases per 100 person-years.[23][26]

Pathophysiology

HIV is a retrovirus that contains the reverse transcriptase enzyme, enabling the conversion of RNA into DNA.[27] HIV is classified into HIV-1 and HIV-2 based on genetic and antigenic characteristics.[28] HIV-1 is the most prevalent worldwide and consists of various groups, including M, N, O, and P.[28] In the United States, group M, serotype B is the most common variant of HIV-1.[29] HIV-2 is common in West Africa.[28] HIV affects cells that express CD4, including T-helper cells, macrophages, astrocytes, and dendritic cells. The co-receptors for the virus on the cells include chemokine receptor 5 and chemokine receptor 4, also known as fusin.[30] In HIV infection, the selective destruction of CD4+ helper T lymphocytes leads to an inverted CD4+/CD8+ ratio of less than 1 (normal value 1-3).[31]

Ocular involvement in patients with HIV infection occurs most commonly due to direct infection by HIV, opportunistic infections, neoplasms, and adverse reactions to therapy.[32][33][34] Direct HIV infection of the vascular endothelium, immune complex deposition, or increased plasma viscosity can lead to microangiopathy that results in HIV retinopathy and HIV-related conjunctival microvasculopathy.[35]

Opportunistic infections such as CMV retinitis occur with a significantly reduced CD4 T-cell count and are one of the common causes of blindness in patients with HIV infection. Ocular infection in these immunosuppressed patients is associated with minimal inflammatory signs. CMV retinitis and progressive outer retinal necrosis are associated with minimal or no vitritis, and the media are clear upon fundus examination.[36] In addition to opportunistic infections, a higher incidence of malignancy, including Kaposi sarcoma, is associated with HIV infection.[37]

HIV has been isolated from tears, corneal epithelial cells, conjunctival epithelial cells, aqueous humor, vitreous humor, retina, and retinal vascular endothelium in affected persons. The ocular structures affected by HIV include the adnexa, anterior segment, posterior segment, and orbit. Neuro-ophthalmological manifestations may also be observed. The introduction of highly active ART (HAART) has markedly improved the immune status of HIV-infected individuals, leading to changes in the clinical presentation and progression of opportunistic infections. However, improvement in immunity may be associated with an inflammatory response called immune recovery uveitis.[38] Drug toxicity of therapeutic agents has also been reported.[13]

History and Physical

Orbital involvement in patients with HIV infection is rare and includes infections, such as orbital cellulitis, caused by various bacteria and fungi, including Aspergillus. Orbital cellulitis may also occur due to the contiguous spread of infections from the sinuses. Symptoms of orbital cellulitis include orbital pain and swelling of the eyelids. Signs of orbital cellulitis include proptosis, limited ocular movements, pain during ocular movements, and decreased vision. Other orbital involvement in patients with HIV infection includes orbital lymphoma. HIV-associated orbital lymphoma is typically of the non-Hodgkin type and involves B cells.[39]

Adnexal involvement in HIV-infected persons may include herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), Kaposi sarcoma, molluscum contagiosum, and blepharitis.

- HZO is a vesiculobullous dermatitis in the course of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). The prevalence of HZO in people with HIV infection is around 15 times higher than that of the general population.[40] HZO may be associated with a simultaneous occurrence of keratitis, scleritis, uveitis, retinitis, or encephalitis. HZO may be very severe in AIDS, and corneal involvement may cause corneal melt.[41] HIV testing should be considered in patients with HZO who are younger than 50. The risk factors of HZO include old age, systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, low CD4+ T-cell counts indicating a more compromised immune system, and lack of ART. Additional risk factors include other immunosuppressing conditions and certain medications. A thorough posterior segment examination is essential to rule out complications such as retinitis, chorioretinitis, retinal vasculitis, and optic neuritis.

- Kaposi sarcoma is a highly vascularized, mesenchymal tumor and may present as painless, violaceous lesions on the eyelid skin or conjunctiva.

- Molluscum contagiosum is caused by a DNA poxvirus and characterized by multiple small, painless, umbilicated, elevated, round lesions on the eyelid skin. This infection may be associated with follicular conjunctivitis. Compared to the immunocompetent patients, molluscum in patients with AIDS may cause multiple and bilateral lesions.

- People with HIV infection are more prone to developing blepharitis, which may be more severe.[42]

Conjunctival manifestations in patients with HIV infection include HIV-related conjunctival microvasculopathy (up to 80%), Kaposi sarcoma, solitary granulomatous conjunctivitis, and ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN).

- Up to 70% to 80% of patients with HIV infection may present with conjunctival microvasculopathy, although its incidence may have reduced after the introduction of HAART.[43][44][45][46][47] This condition is characterized by segmental dilatation and narrowing of blood vessels, comma-shaped vascular segments, and sludging of the blood column. The cause is thought to be either immune complex deposition, increased plasma viscosity, abnormalities of the blood flow, or invasion of vascular endothelium by HIV.

- Kaposi sarcoma of the conjunctiva presents as a conjunctival vascular lesion and may result in subconjunctival hemorrhages. This condition is associated with human herpesvirus-8. Histopathology shows spindle cells with vascular structures.

- Solitary granulomatous conjunctivitis may arise from TB, fungal infection, or cryptococcal infection. Systemic involvement should be ruled out in such cases.

- OSSN in HIV-positive individuals is characterized by larger, more aggressive tumors and increased risk of invasion into surrounding tissues such as the cornea, sclera, and orbit. These individuals tend to be younger at diagnosis, and the tumors are more likely to be high-grade and invasive, leading to poorer ocular prognosis and a higher need for extensive surgical interventions such as enucleation or exenteration.[48]

Anterior segment involvement in patients with HIV infection includes keratoconjunctivitis sicca, keratitis, and iridocyclitis.

- Keratoconjunctivitis sicca, also known as dry eye syndrome, is observed in approximately 20% to 25% of patients with HIV infection.[49] This condition is thought to be an HIV-mediated inflammatory destruction of lacrimal glands.[50]

- Keratitis in patients with HIV infection is rare, affecting around 5% of cases, but can lead to vision loss.[51] Herpes simplex virus (HSV) and VZV are the most common causes. These viruses may be recurrent, severe, more prone to corneal melt, and resistant to treatment. Microsporidia are protozoa that can cause punctate epithelial keratopathy with minimal conjunctival congestion. Bacterial and fungal keratitis can also occur without apparent predisposition, such as trauma or steroid use.

- Iridocyclitis is relatively common in people with HIV infection. HIV itself may cause acute anterior uveitis or posterior uveitis that responds well to ART, although uveitis may not respond well to steroids.[52] Mild iridocyclitis may be observed in association with VZV or CMV retinitis, and severe iridocyclitis in association with toxoplasmosis, syphilis, TB, and bacterial or fungal retinitis. Certain medications, such as rifabutin and cidofovir, prescribed for patients with HIV infection, may also cause iridocyclitis. Clinical examination in cases of iridocyclitis may reveal keratic precipitates, anterior chamber cells, patches of iris necrosis, posterior synechiae, and hypopyon.

Posterior segment involvement in patients with HIV infection is quite common and can cause visual loss. Conditions include retinal microangiopathy, CMV retinitis, VZV retinitis, toxoplasma retinochoroiditis, and bacterial and fungal retinitis.[53] Patients may complain of floaters, flashes of light, decreased visual acuity, or visual field defects.

- Retinal microangiopathy is the most common ophthalmic manifestation of HIV, occurring in up to 70% of patients.[33][54] The cotton wool spots, retinal hemorrhages, and capillary abnormalities, including microaneurysms, are noted. The pathogenesis is thought to be similar to that of conjunctival microvasculopathy, including HIV infection of the endothelium and rheologic abnormalities. Retinal microangiopathy is associated with low CD4+ T-cell counts and high plasma HIV RNA levels.[55] These patients may be at higher risk of developing CMV retinitis. Contrary to CMV retinitis, these lesions are smaller, asymptomatic, and resolve spontaneously within weeks.

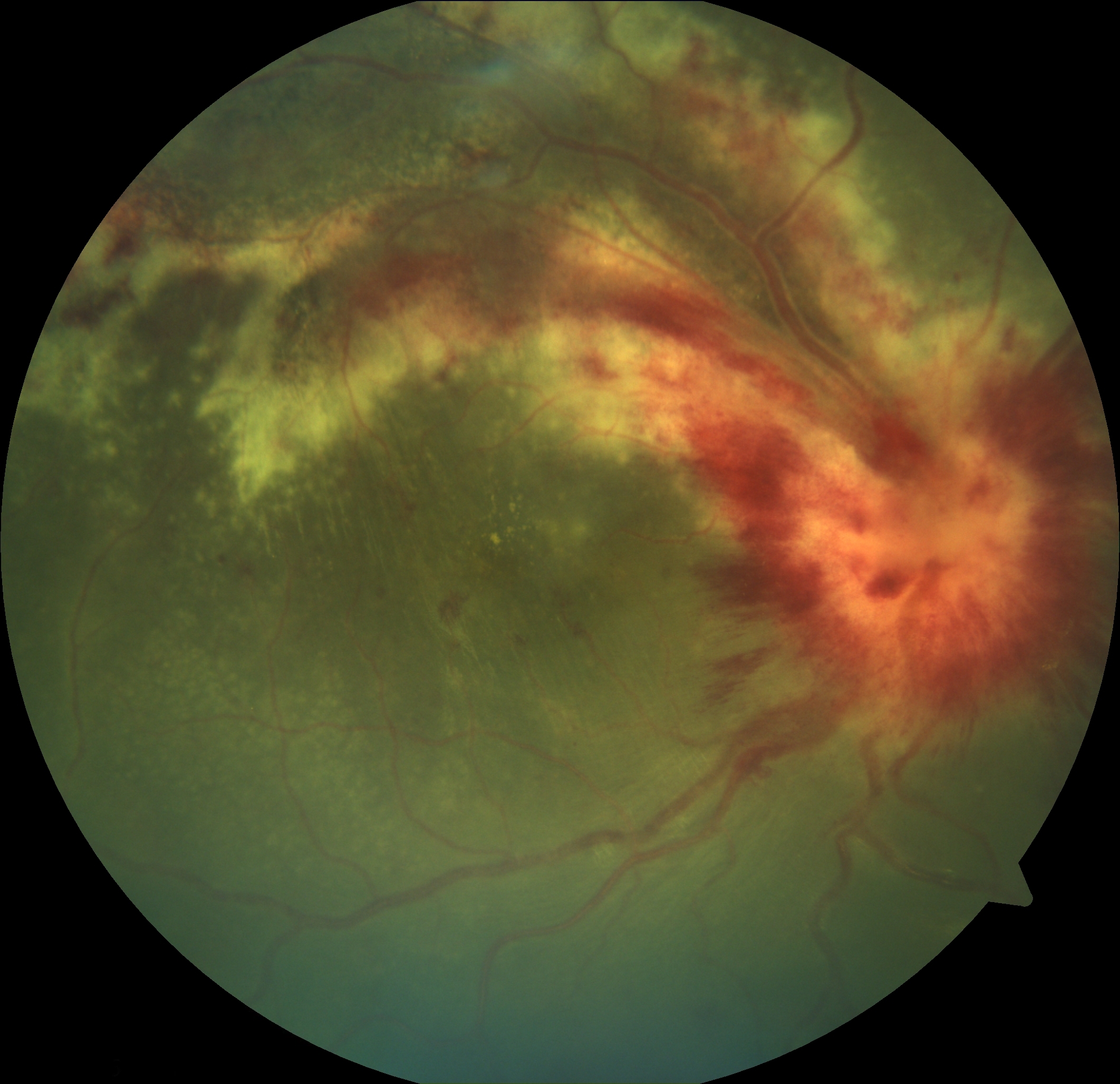

- CMV retinitis affected nearly 30% to 45% of HIV-infected individuals in the pre-HAART era.[56][57] CMV retinitis is usually observed in individuals with AIDS with CD4 counts less than 50 cells/µL.[25] Fundus examination reveals full-thickness intraretinal opacification associated with retinal hemorrhages (see Image. Cytomegalovirus and Associated Hemorrhages). There is minimal anterior chamber reaction, and the vitreous is generally clear (no vitritis). Loss of vision can occur due to the direct involvement of the macula or optic nerve, retinal detachment, and immune recovery uveitis. The zones of involvement in CMV retinitis are as follows:

- Zone 1: This zone is defined as the region in the posterior pole of the retina that is within 1500 µm of the optic disc and 3000 µm of the foveal center.

- Zone 2: This zone is an area peripheral to Zone 1 and posterior to the vortex veins (equator).

- Zone 3: This zone is denoted by the peripheral retina anterior to the equator.[58]

Widespread use of HAART has caused a change in the natural history of CMV retinitis, leading to a marked reduction in the incidence of this condition and clinical findings not observed in classical CMV retinitis, such as anterior chamber and vitreous inflammation. Other posterior segment manifestations of CMV infection include a granular pattern of retinitis and frosted branch angiitis. CMV retinitis is increasingly becoming uncommon in areas with wide availability of HAART. However, it remains a major challenge in resource-limited areas, including Southeast Asia. CMV retinitis is still the most common opportunistic intraocular infection in individuals with AIDS.[59]

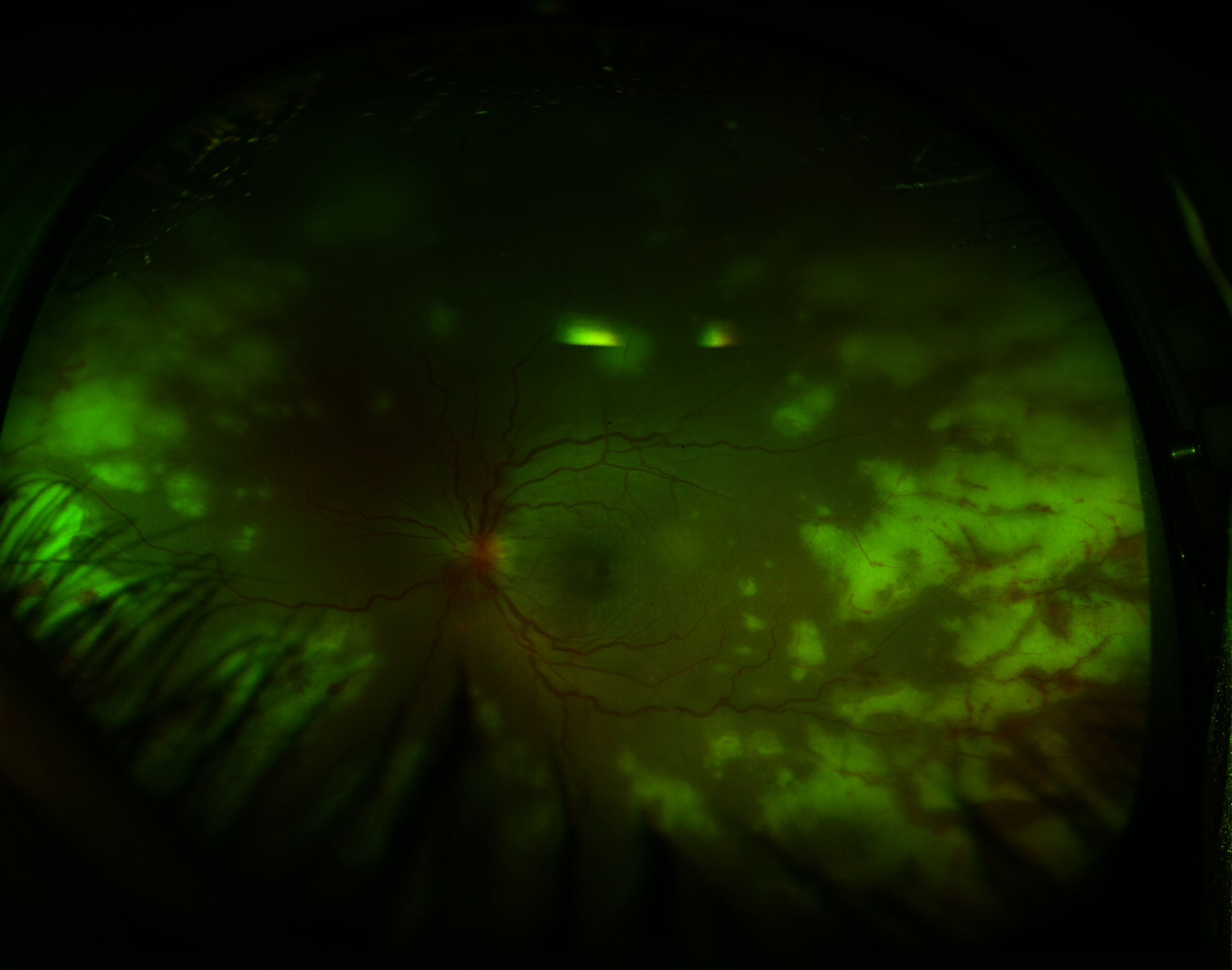

- Necrotizing herpetic retinitis, typically caused by VZV or HSV, is characterized by retinal whitening and necrosis. Necrotizing herpetic retinitis may be associated with skin lesions. Acute retinal necrosis is characterized by peripheral circumferential retinitis patches (see Image. Acute Retinal Necrosis), which may be nonconfluent in the early stages (see Table. Differential Diagnosis of Retinitis in Patients with HIV Infection).[60] In typical cases of acute retinal necrosis, the anterior chamber shows cells, and vitritis is present, although the inflammatory response may be less pronounced in severely immunocompromised patients. Involvement of the retinal arterioles and optic nerve head is common in acute retinal necrosis. Progressive outer retinal necrosis is characterized by retinal whitening in the posterior pole, particularly in severely immunocompromised patients with a lack of vitritis. Paravascular sparing or clearing is a peculiar feature in progressive outer retinal necrosis that results in a cracked mud appearance. A majority of patients with progressive outer retinal necrosis experience vision loss, although HAART and antiviral drugs may preserve vision.[61]

- Toxoplasma retinochoroiditis in patients with HIV infection is typically atypical, larger, bilateral (in 40%), multifocal, and may be associated with CNS involvement or disseminated toxoplasmosis.[62] The vitritis is typically less marked, but vitreous cells are generally present overlying the area of retinitis. A military toxoplasma retinitis is described in AIDS, which is characterized by multiple small round lesions in both eyes.[63] In patients with AIDS, ocular toxoplasmosis can stem from newly acquired infections or reactivation from other body sites, often lacking the classic retinal scars, which complicates diagnosis.[64] Ocular toxoplasmosis can mimic other retinal conditions, including necrotizing herpetic retinitis, acute retinal necrosis, and syphilitic retinitis. Ocular toxoplasmosis typically presents with milder inflammation in patients with AIDS than in immunocompetent patients, but shows a higher density of Toxoplasma gondii organisms invading ocular tissues on histopathological examination. Because it progresses rapidly in immunocompromised individuals and may be linked to cerebral involvement, prompt diagnosis using PCR or culture of the aqueous or vitreous and neuroimaging is crucial to avoid severe morbidity.[65]

- Ocular syphilis is typically more aggressive in patients with AIDS than in immunocompetent persons.[66] There is a global resurgence of ocular syphilis, particularly among individuals with HIV coinfection. Clinical presentations include scleritis, uveitis (anterior, posterior, or intermediate), or optic neuritis, often with systemic symptoms. In patients with AIDS, hallmark findings include pale-yellow placoid macular lesions (syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis) and superficial retinal precipitates, with vitritis sometimes appearing as the initial sign, even without chorioretinitis. These findings are diagnostically important, as they may mimic other ocular infections, and syphilitic involvement of the CNS should be considered.[67]

- Ocular TB may present as multiple small tubercles, a tuberculoma, or a subretinal abscess.[68][69][70][71]

- Pneumocystis, Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, TB, or atypical mycobacteria may cause infectious choroiditis.[72] Coinfections with multiple microbes may be present, and disseminated systemic infections should be ruled out in such cases.

- Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly Pneumocystis carinii) causes pneumonia, which is an AIDS-defining disease. Pneumocystis choroiditis is characterized by good vision and multifocal, plaque-like, slightly elevated choroidal lesions.[73]

- Cryptococcus neoformans causes meningitis, optic disc edema due to high intracranial pressure, direct invasion of the optic nerve, and multifocal choroiditis.[74] Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations include nystagmus, cranial nerve palsy, and ophthalmoplegia.[75]

- Intraocular lymphoma has 2 variants—uveal lymphoma and vitreoretinal lymphoma. Primary intraocular lymphoma (PIOL) or vitreoretinal lymphoma is frequently a type of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). HIV-positive patients are 15 to 20 times more likely to develop primary CNS lymphoma or vitreoretinal lymphoma when CD4 counts go below 50 cells/µL.[76] These patients are more likely to be male and younger than immunocompetent patients.[77] Lymphoma can be confined to the eye (primary) or occur in association with systemic lymphoma and CNS lymphoma. Epstein-Barr virus infection is frequently linked to both intraocular lymphoma and CNS lymphoma in the context of HIV.[76]

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is a paradoxical inflammatory reaction that occurs after starting ART, where a recovering immune system responds aggressively to either previously treated infections or previously undiagnosed ones.[78] IRIS manifests in 2 patterns—one where known opportunistic infections worsen despite improved HIV markers, and another where hidden infections become clinically apparent.

Immune recovery uveitis is a type of IRIS observed in patients with AIDS with prior CMV retinitis who experience immune improvement after starting combination ART. Immune recovery uveitis typically arises when CD4+ T-cell counts increase by at least 50 cells/µL to reach 100 cells/µL or more. Risk factors include the extent of CMV retinitis involvement, intraocular CMV antigen load, speed of immune restoration, and prior treatment, especially with cidofovir.[38] Immune recovery uveitis can manifest in several ways, such as anterior uveitis, vitritis, macular edema, epiretinal membrane, optic disc edema, and neovascularization of the optic disc or retina.[38][79]

Neurophthalmic manifestations are observed in up to 60 % of patients with HIV infection and include papilledema, cranial nerve palsies, ocular motility disorders, and visual field defects.[80] Common causes include cryptococcal meningitis, CNS lymphoma, neurosyphilis, and toxoplasmosis.[80]

Ocular toxicities may develop in patients receiving medications for HIV or opportunistic infections. These toxicities include uveitis with cidofovir and rifabutin, retinal pigment epithelial abnormalities with high-dose didanosine, corneal epithelial inclusions with intravenous (IV) cidofovir or acyclovir, and corneal subepithelial deposits with atovaquone.[81]

Ocular manifestations of HIV in children may be less common (20%-54%) than in adults (50%-90%).[82] Common ocular features of HIV infection include dry eye, allergic conjunctivitis, and retinal perivasculitis.[82] Children may have a lower incidence of CMV retinitis and are also at risk of neurodevelopmental delay.[83][84] Features such as growth restriction, microcephaly, prominent box-like forehead, hypertelorism, flat nasal bridge, long palpebral fissure, obliquity of eyes, blue sclera, and well-formed philtrum have been described as AIDS-associated embryopathy—also referred to as AIDS dysmorphic syndrome or HIV embryopathy. However, the clinical existence of this entity has been debated.[85][86][87]

HIV may accelerate aging and cause the earlier onset of cataracts and macular degeneration.[88] This phenomenon is due to a combination of factors, including chronic inflammation, immune system dysregulation, and the impact of ART.[89][90]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of HIV requires an initial screening test with high sensitivity, such as an antigen/antibody combination test to detect both antigen (p24) and antibodies (immunoglobulin G and M). This test is followed by a confirmatory test with high specificity, such as an immunoglobulin G–sensitive HIV-1/2 antibody differentiation supplemental assay, which is a faster replacement for the Western blot.[91] Nucleic acid tests detect HIV very early. The HIV-RNA or viral load helps to monitor the response to therapy, risk of transmission, progression to AIDS, and risk of death.[92]

The CD4 T-cell count provides insight into the degree of immunosuppression and is used to classify patients according to CDC categories:

- Category 1: ≥500 cells/mL

- Category 2: 200-499 cells/µL

- Category 3: <200 cells/µL [93]

All newly diagnosed patients with HIV infection should undergo a comprehensive eye examination and investigation for opportunistic infections, including CMV, TB, syphilis, Toxoplasmosis, gonococcus, chlamydia, hepatitis A-C, and Pneumocystis.

Given the wide range of HIV-related ocular manifestations, a detailed history and a thorough evaluation are essential. A detailed history, disease progression by monitoring CD4 counts, slit lamp examination, and dilated fundoscopy are useful. The CD4 T-cell count and, more recently, viral load can be taken as a predictor of ocular involvement in patients with HIV infection. Visual acuity, visual field testing, ocular movement testing, pupillary examination, and fundus examination are important in detecting various infections and other conditions associated with HIV.

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca requires dry eye evaluation with tests such as the Schirmer test and Rose Bengal staining. Gram staining and cultures may be performed in cases of keratitis when the cause is not obvious. Dilated fundus examination can diagnose posterior segment involvement with a direct or indirect ophthalmoscope. Additional investigations may include the venereal disease research laboratory test, the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test, and tests for TB. Orbital involvement typically requires a computed tomography scan, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a biopsy, and a culture. Evaluation of a patient with HIV infection presenting with neuro-ophthalmological manifestations requires MRI and lumbar puncture for cytology, culture, and antigen-antibody testing. Patients with necrotizing retinitis may need a vitreous biopsy for polymerase chain reaction to detect microbes, including VZV, HSV, CMV, Toxoplasma, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[94] Patients with suspected intraocular lymphoma may need an MRI of the brain and a vitreous with or without a chorioretinal biopsy.[95]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of ocular manifestations depends on the presenting ocular pathology and the use of HAART. HAART should be initiated as early as possible. The goal of therapy includes reduction of viral load, improvement of immune status, prevention of opportunistic infections, transmission, and drug resistance, and improvement of quality of life.[96] The medications for HIV include a combination of antiretroviral medications:

- Backbone regimen: This regimen refers to the 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors that form the foundation of an initial HIV treatment regimen.

- Base medication: These 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors are combined with a third antiretroviral drug from another class, such as a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, a protease inhibitor, or an integrase strand transfer inhibitor, to create a complete treatment regimen. This combination of drugs is crucial for effectively suppressing the virus and preventing the development of drug resistance.[97]

Treatment of HZO includes systemic acyclovir, famciclovir, valacyclovir, and, in resistant cases, IV foscarnet.[98] Molluscum contagiosum can be treated with cryotherapy, curettage, and surgical excision.[99][100]

Treatment of keratoconjunctivitis sicca includes lubricants. Keratitis is treated depending on the cause—viral keratitis is treated with oral acyclovir or famciclovir; microsporidial keratitis is treated with oral itraconazole, topical fumagillin, and oral albendazole; and bacterial and fungal keratitis is treated with appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Iridocyclitis is typically treated with topical corticosteroids, which are initiated only after proper antimicrobial therapy has been instituted if an infection is suspected.[101][102][101]

CMV retinitis is treated with drugs such as oral valganciclovir, oral or IV ganciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir.[36][103] Intravitreal antiviral agents, including ganciclovir, are frequently needed.[103] Patients with progressive outer retinal necrosis typically become blind; however, prompt initiation of antiviral therapy, including IV acyclovir, intravitreal ganciclovir injection or implant (not commercially available currently), intravitreal foscarnet, and HAART, may prevent vision loss.[61] Patients with acute retinal necrosis are treated with similar agents as progressive outer retinal necrosis; however, the vitritis and ocular inflammation may need steroids under antiviral cover in immunocompetent patients.[60]

Management of ocular toxoplasmosis involves a combination of anti-toxoplasmic therapy using drugs such as pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, atovaquone, and clindamycin. Corticosteroids may be used cautiously alongside proper antimicrobial coverage. Steroids can cause further immunosuppression. Clinicians should assess for possible cerebral or disseminated toxoplasmosis in AIDS and monitor for bone marrow toxicity, with ongoing maintenance therapy considered for patients with persistently compromised immunity.[104]

The recommended regimen for ocular syphilis includes 18 to 24 million units of IV penicillin G daily for 10 to 14 days, followed by 3 weekly intramuscular doses of benzathine penicillin G at 2.4 million units each.[105] Ongoing monitoring through quantitative rapid plasma reagin testing is essential, as symptomatic relapses can occur despite treatment.[67]

Treatment of Pneumocystis choroiditis involves systemic trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole or pentamidine. A response is typically noted within 1 to 3 months.[106] Cryptococcus choroiditis and meningitis are managed with systemic amphotericin and flucytosine.[75] Treatment for histoplasma choroiditis in patients with HIV infection typically involves a combination of antifungal medications and HAART. Initial treatment often includes IV liposomal amphotericin B, followed by oral itraconazole for maintenance. HAART is crucial for managing the underlying HIV infection and preventing future opportunistic infections such as histoplasmosis.[107][108][107] For chorioidal TB, antitubercular therapy should be started along with HAART. (A1)

The management of neuro-ophthalmic manifestations of HIV infection requires a multidisciplinary approach, focusing on both treating the underlying HIV infection and opportunistic infections and addressing the specific ocular or neurological complications. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent vision loss and other neurological impairments.[109]

The approach to treating Kaposi sarcoma includes surgery, cryotherapy, radiation, or a combination of these techniques.[110] The chosen method depends on the tumor's clinical stage, its location, and whether or not there are disseminated lesions present. Ocular and periocular lymphoma in patients with AIDS requires a multifaceted management approach, primarily focusing on controlling local disease and preventing CNS spread. Treatment strategies include radiation therapy for localized ocular adnexal lymphoma; chemotherapy administered intravitreally, IV, or intrathecally; and potentially immunotherapy with rituximab, often used in combination.[111] Intravitreal methotrexate has been used with success in intraocular lymphoma.[112] Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma management primarily involves surgical excision with wide margins to ensure complete removal of the tumor. Adjuvant therapies such as cryotherapy, chemotherapy (mitomycin C, 5-fluorouracil, interferon), and radiotherapy may be used to reduce recurrence rates. In cases of extensive involvement, more radical procedures such as exenteration may be necessary.[113] (A1)

Management of immune recovery uveitis needs systemic or local steroids. However, this can lead to the recurrence of CMV retinitis. Thus, a risk-benefit analysis should be done before initiating steroids. Some cases of cataract and epiretinal membrane may need surgery.[38]

For adverse reactions related to medications, the offending medications should be stopped.

Differential Diagnosis

Various causes of retinitis in patients with HIV infection include CMV retinitis, acute retinal necrosis, progressive outer retinal necrosis, and toxoplasma retinochoroiditis.[114] Acute retinal necrosis and progressive outer retinal necrosis may represent a spectrum of the same disease. In individuals with AIDS, distinguishing between the various causes of retinitis can be clinically challenging. However, initiation of treatment should not be delayed solely due to the absence of a microbiological diagnosis, as the disease can progress rapidly, and irreversible damage to vision or involvement of the other eye can occur without therapy.[36]

Table 2. Differential Diagnosis of Retinitis in Patients with HIV Infection

| Feature | Cytomegalovirus Retinitis | Acute Retinal Necrosis | Progressive Outer Retinal Necrosis |

Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis |

| Immunity | Involves immunocompromised patients, patients with AIDS, hematological diseases, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and those on immunosuppressive drugs. | Immunocompetent or immunocompromised individuals can have ARN. | Severely immunocompromised patients are typically affected. | The affected individual may be immunocompetent or immunocompromised. |

| Laterality | CMVR is typically unilateral (65%) at diagnosis. Around 50% of patients develop bilateral disease in 6 months if left untreated.[115] | ARN is typically unilateral (66%-90%) in immunocompetent patients.[116] Up to 60% of patients can have eventual bilateral involvement in AIDS.[117] | Progressive outer retinal necrosis is eventually bilateral at final follow-up (71%).[118] | Active toxoplasma retinitis is typically unilateral (in up to 92.4% of cases).[104][119] Toxoplasma retinitis can be bilateral in AIDS.[120] |

| Symptoms | Reduced vision occurs when the macula or optic nerve is involved. | Reduced vision with floaters, redness, photophobia, and pain. | Severe reduction of vision. | Floaters, photophobia, and dimness of vision. |

| Anterior segment inflamamtion | Anterior segment inflammation is typically absent or mild. A severe anterior chamber reaction may be observed in immune recovery uveitis, characterized by cells and fibrin, with or without posterior synechia. | Typical findings include moderate-to-severe inflammation with anterior chamber cells, fibrin, and posterior synechia (if not treated early) in a painful red eye.[121] The anterior segment inflammation may be less severe in immunocompromised patients with AIDS. | Typically, the anterior chamber is quiet. Mild anterior chamber or vitreous reaction may be noted in around 33% of cases.[118] | Typically, the anterior chamber reaction is mild to moderate. The anterior segment inflammation may be less severe in immunocompromised patients with AIDS. |

| Vitritis | Vitritis is typically absent (clear media). | Vitritis is typically moderate to severe. Severely immunocompromised patients may have less marked vitritis. | Typically, vitiritis is absent (clear media). | Vitritis is typically severe (headlight in the fog appearance). Severely immunocompromised patients may have less marked vitritis. |

| Location and appearance |

The typical patterns include:

|

Typically, the peripheral retina is involved. Isolated multifocal lesions gradually become confluent at the peripheral retina and then progress posteriorly if not treated. | Multifocal outer retinal round retinitis patches are scattered in the periphery, with frequent involvement of the macula (32%) at presentation.[118] Eventually, most lesions coalesce and progress posteriorly to involve the macula and fovea. | Usually, the posterior pole is involved in more than half of the cases.[123] However, retinitis may involve any part of the retina. |

| Hemorrhages | Hemorrhages form a crucial part of the classic pizza-pie (or cottage cheese with ketchup) appearance. | Hemorrhage may or may not be present. | Hemorrhage is usually absent, but may be present.[124] | Typically, hemorrhage is not observed. |

| Retinal involvement | The full thickness of the retina is affected. | The full thickness of the retina is affected. | Involvement is predominantly outer retinal, though late stages can have inner retinal/full-thickness involvement.[125] | Typically, the lesions involve the full thickness of the retina.[126] Early lesions can be inner retinal. Punctate outer retinal toxoplasmosis lesions have been described.[127] |

| Retinal vascular involvement (vasculitis) | Typically, veins are involved. | Occlusive arteriolitis is typical. Periarterial plaques (Kyrieleis arteriolitis) may be noted.[128] | Vasculitis is not common. There is paravascular clearing, or the paravascular retina is not involved, which later gives rise to the typical cracked mud appearance. | Vasculitis is common (10%-35%), and sheathing around veins or arteries may be noted.[57][122][129][130] Kyrieleis arteriolitis may be noted.[57] |

| Retinal detachment | Common (up to 50%).[131] HAART can lead to a 60% reduction in the rate of retinal detachment.[131][132] | Very common (50%-75%).[60][133] | Occurs in up to 70% of cases.[134] | Uncommon. Risk factors include severe inflammation, myopia, age, history of trauma, cataract surgery, and extensive peripheral scarring.[135] |

| Optic nerve involvement in early stages | Uncommon | Very common | Initially, around 17% eyes have optic nerve involvement, though eventually, the optic nerve is involved in most cases, leading to loss of light perception.[118] | Uncommon |

| Progression | Slow | Rapid | Rapid | Slow. However, it can progress very rapidly in severe immunosuppression. |

| Treatment (along with HAART in patients with HIV infection) | Oral valganciclovir or IV ganciclovir with or without intravitreal ganciclovir | Oral valaciclovir or IV aciclovir. Intravitreal injections may also be needed. Immunocompetent patients typically need oral/intravitreal steroids under the cover of antivirals. | Aciclovir, ganciclovir, and foscarnet | Cotrimoxazole. Immunocompetent patients typically need oral/intravitreal steroids under the cover of antimicrobial agents. |

Abbreviations: ARN, acute retinal necrosis; CMVR, cytomegalovirus retinitis; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; IV, intravenous.

Prognosis

The prognosis of ocular manifestations in patients with HIV infection has significantly improved with the advent of combination ART, leading to a decline in opportunistic infections such as CMV retinitis.[136] However, late presentation or poor adherence to treatment may still result in severe vision loss or blindness from progressive retinal necrosis and retinal detachment. HIV-related microvasculopathy, although typically asymptomatic, may indicate systemic disease progression and worsen with declining CD4+ counts. Immune recovery uveitis, a paradoxical inflammation that occurs during immune reconstitution, can lead to complications such as cystoid macular edema and epiretinal membrane formation, necessitating vigilant follow-up and prompt treatment.[137] The incidence of ocular syphilis, HZO, and ocular TB remains notable in patients with HIV infection with suboptimal immune control, potentially affecting visual outcomes. Long-term visual prognosis depends on timely diagnosis, effective control of systemic HIV infection, and management of ocular complications. Therefore, regular ophthalmic screening and interdisciplinary care are vital to preserving vision and quality of life in HIV-infected individuals.[138]

Complications

Retinal detachment is a common complication in CMV retinitis, affecting up to 50% of cases, and can occur during active disease or after resolution. The introduction of potent ART has drastically reduced its incidence to just 0.06 per patient-year.[139] Key risk factors include involvement of all 3 retinal zones, extensive retinitis, and low CD4+ T-cell counts. Surgical repair often involves a pars plana vitrectomy with silicone oil tamponade, resulting in successful anatomical reattachment in 70% to 90% of patients with CMV retinitis.[140][141] However, the visual prognosis is typically poor due to optic atrophy and macular atrophy. Final visual acuity was found to be better in patients who initiated HAART before the occurrence of retinal detachment, had better preoperative vision, showed no evidence of optic atrophy or retinal redetachment, and underwent vitrectomy within 3 months.[141]

Around 50% to 75% of patients with acute retinal necrosis develop retinal detachment, and the breaks are similar to holes in a sieve, typically occurring at the junction between the healthy and necrotic retina.[60][142] Progressive outer retinal necrosis is typically observed in patients with CD4+ T-cell counts less than 50 cells/µL and is often associated with cutaneous zoster. Around 70% of cases of progressive outer retinal necrosis develop retinal detachment.[118] Up to 67% of eyes with progressive outer retinal necrosis can lose perception of light; however, recent advances in both systemic and intravitreal therapies have expanded available management options and may preserve vision in some patients.[118] Choroiditis may be associated with a choroidal neovascular membrane.[143][144]

Systemic and CNS involvement may be present in various ocular infections in AIDS, including CMV retinitis, necrotizing herpetic retinitis, ocular toxoplasmosis, ocular syphilis, pneumocystis choroiditis, tubercular choroiditis, and cryptococcal choroiditis.[145]

HZO in patients with AIDS is aggressive and may be associated with skin ulcers, corneal melt, and viremia with neurological and systemic infection.[146] Keratitis in patients with AIDS may lead to corneal perforation.[147]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Early and consistent use of ART significantly reduces the incidence of opportunistic ocular infections and vision-threatening complications in patients with HIV infection. Routine ophthalmic screening is strongly recommended, especially in individuals with low CD4 counts, as subtle ocular symptoms may precede irreversible damage. Patients should be counseled to recognize early visual symptoms such as floaters, blurred vision, or field loss, which may indicate retinitis or uveitis and warrant immediate ophthalmological evaluation. Education about HIV-associated ocular diseases, including CMV retinitis, toxoplasmosis, HZO, and neuro-ophthalmic complications, empowers patients to seek timely care and improves adherence to follow-up.[96] Interprofessional collaboration among infectious disease specialists, ophthalmologists, pharmacists, and primary care providers enhances care coordination and supports public health efforts to reduce preventable vision loss in patients with HIV infection through early intervention and patient engagement.[148]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

With the widespread use of HAART and the advent of better medications, the lifespan of patients with HIV infection is increasing.[149] Patients with HIV infection can develop ocular manifestations and have an increased risk of visual loss. HIV is a disorder that affects many organs, and thus, it is best managed by an interprofessional team. Patients with HIV infection presenting with visual complaints should be referred to an ophthalmologist. Comprehensive eye examination in HIV-infected individuals should be conducted. Health education regarding the ocular manifestations of HIV and complications increases awareness, reduces morbidity, and improves the quality of life.[150]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Acute Retinal Necrosis. Retinitis is demonstrated by the peripheral whitish retinal lesions. Typical additional findings include vitreous involvement and a paucity of hemorrhages, as opposed to cytomegalovirus retinitis, which presents with no vitreous involvement and a prominence of hemorrhages.

Contributed by K Tripathy, MD

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Twenty-five years of HIV/AIDS--United States, 1981-2006. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2006 Jun 2:55(21):585-9 [PubMed PMID: 16741493]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pneumocystis pneumonia--Los Angeles. 1981. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 1996 Aug 30:45(34):729-33 [PubMed PMID: 8778581]

Maclean H, Hall AJ, McCombe MF, Sandland AM. AIDS and the eye. A 10-year experience. Australian and New Zealand journal of ophthalmology. 1996 Feb:24(1):61-7 [PubMed PMID: 8743007]

Swain J, Sharma PK, Mohanty L, Panigrahi PK. Ocular manifestations in HIV patients attending a tertiary care hospital in Eastern India and correlation of posterior segment lesions with CD4+ counts. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2023 Dec 1:71(12):3701-3706. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_942_23. Epub 2023 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 37991307]

Pan X, Baldauf HM, Keppler OT, Fackler OT. Restrictions to HIV-1 replication in resting CD4+ T lymphocytes. Cell research. 2013 Jul:23(7):876-85. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.74. Epub 2013 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 23732522]

Merchant RC, Nettleton JE, Mayer KH, Becker BM. Blood or body fluid exposures and HIV postexposure prophylaxis utilization among first responders. Prehospital emergency care. 2009 Jan-Mar:13(1):6-13. doi: 10.1080/10903120802471931. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19145518]

Swinkels HM, Huynh K, Gulick PG. HIV Prevention. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261888]

Battistini Garcia SA, Zubair M, Guzman N. CD4 Cell Count and HIV. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020661]

. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. 2016:(): [PubMed PMID: 27466667]

Weinberg JL, Kovarik CL. The WHO Clinical Staging System for HIV/AIDS. The virtual mentor : VM. 2010 Mar 1:12(3):202-6. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2010.12.3.cprl1-1003. Epub 2010 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 23140869]

Chiotan C, Radu L, Serban R, Cornăcel C, Cioboata M, Anghel A. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV/AIDS patients. Journal of medicine and life. 2014 Jun 15:7(2):237-40 [PubMed PMID: 25408732]

Dheda M. Efavirenz and neuropsychiatric effects. Southern African journal of HIV medicine. 2017:18(1):741. doi: 10.4102/sajhivmed.v18i1.741. Epub 2017 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 29568641]

Dash S, Mohanty SK, Mohanty G. Ocular Complications in Patients on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023 Oct:15(10):e47242. doi: 10.7759/cureus.47242. Epub 2023 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 38022310]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan Schalkwyk C, Mahy M, Johnson LF, Imai-Eaton JW. Updated Data and Methods for the 2023 UNAIDS HIV Estimates. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2024 Jan 1:95(1S):e1-e4. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000003344. Epub 2024 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 38180734]

Mutanga JN, Ronan A, Powis KM. Achieving equity for children and adolescents with perinatal HIV exposure: an urgent need for a paradigm shift. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2023 Oct:26 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):e26171. doi: 10.1002/jia2.26171. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37909238]

Wang L, Che X, Jiang J, Qian Y, Wang Z. New Insights into Ocular Complications of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Current HIV research. 2021:19(6):476-487. doi: 10.2174/1570162X19666210812113137. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34387164]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKestelyn PG, Cunningham ET Jr. HIV/AIDS and blindness. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2001:79(3):208-13 [PubMed PMID: 11285664]

Feroze KB, Gulick PG. HIV Retinopathy. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261911]

Luo J, Jing D, Kozak I, Huiming Z, Siying C, Yezhen Y, Xin Q, Luosheng T, Adelman RA, Forster SH. Prevalence of ocular manifestations of HIV/AIDS in the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era: a different spectrum in Central South China. Ophthalmic epidemiology. 2013 Jun:20(3):170-5. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2013.789530. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23713918]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGharai S, Venkatesh P, Garg S, Sharma SK, Vohra R. Ophthalmic manifestations of HIV infections in India in the era of HAART: analysis of 100 consecutive patients evaluated at a tertiary eye care center in India. Ophthalmic epidemiology. 2008 Jul-Aug:15(4):264-71. doi: 10.1080/09286580802077716. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18780260]

Ng WT, Versace P. Ocular association of HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy and the global perspective. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2005 Jun:33(3):317-29 [PubMed PMID: 15932540]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAusayakhun S, Watananikorn S, Ittipunkul N, Chaidaroon W, Patikulsila P, Patikulsila D. Epidemiology of the ocular complications of HIV infection in Chiang Mai. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet. 2003 May:86(5):399-406 [PubMed PMID: 12859094]

Stewart MW. Optimal management of cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2010 Apr 26:4():285-99 [PubMed PMID: 20463796]

Kuppermann BD, Petty JG, Richman DD, Mathews WC, Fullerton SC, Rickman LS, Freeman WR. Correlation between CD4+ counts and prevalence of cytomegalovirus retinitis and human immunodeficiency virus-related noninfectious retinal vasculopathy in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. American journal of ophthalmology. 1993 May 15:115(5):575-82 [PubMed PMID: 8098183]

Pertel P, Hirschtick R, Phair J, Chmiel J, Poggensee L, Murphy R. Risk of developing cytomegalovirus retinitis in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 1992:5(11):1069-74 [PubMed PMID: 1357151]

Jabs DA, Van Natta ML, Holbrook JT, Kempen JH, Meinert CL, Davis MD, Studies of the Ocular Complications of AIDS Research Group. Longitudinal study of the ocular complications of AIDS: 1. Ocular diagnoses at enrollment. Ophthalmology. 2007 Apr:114(4):780-6 [PubMed PMID: 17258320]

Hu WS, Hughes SH. HIV-1 reverse transcription. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012 Oct 1:2(10):. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006882. Epub 2012 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 23028129]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGerman Advisory Committee Blood (Arbeitskreis Blut), Subgroup ‘Assessment of Pathogens Transmissible by Blood’. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Transfusion medicine and hemotherapy : offizielles Organ der Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Transfusionsmedizin und Immunhamatologie. 2016 May:43(3):203-22. doi: 10.1159/000445852. Epub 2016 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 27403093]

Magiorkinis G, Angelis K, Mamais I, Katzourakis A, Hatzakis A, Albert J, Lawyer G, Hamouda O, Struck D, Vercauteren J, Wensing A, Alexiev I, Åsjö B, Balotta C, Gomes P, Camacho RJ, Coughlan S, Griskevicius A, Grossman Z, Horban A, Kostrikis LG, Lepej SJ, Liitsola K, Linka M, Nielsen C, Otelea D, Paredes R, Poljak M, Puchhammer-Stöckl E, Schmit JC, Sönnerborg A, Staneková D, Stanojevic M, Stylianou DC, Boucher CAB, SPREAD program, Nikolopoulos G, Vasylyeva T, Friedman SR, van de Vijver D, Angarano G, Chaix ML, de Luca A, Korn K, Loveday C, Soriano V, Yerly S, Zazzi M, Vandamme AM, Paraskevis D. The global spread of HIV-1 subtype B epidemic. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 2016 Dec:46():169-179. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.05.041. Epub 2016 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 27262355]

Moore JP, Trkola A, Dragic T. Co-receptors for HIV-1 entry. Current opinion in immunology. 1997 Aug:9(4):551-62 [PubMed PMID: 9287172]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFrancis-Morris A, Mackie NE, Eliahoo J, Ramzan F, Fidler S, Pollock KM. Compromised CD4:CD8 ratio recovery in people living with HIV aged over 50 years: an observational study. HIV medicine. 2020 Feb:21(2):109-118. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12800. Epub 2019 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 31617962]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMoraes HV Jr. Ocular manifestations of HIV/AIDS. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2002 Dec:13(6):397-403 [PubMed PMID: 12441844]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCunningham ET Jr, Margolis TP. Ocular manifestations of HIV infection. The New England journal of medicine. 1998 Jul 23:339(4):236-44 [PubMed PMID: 9673303]

Robinson MR, Ross ML, Whitcup SM. Ocular manifestations of HIV infection. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 1999 Dec:10(6):431-7 [PubMed PMID: 10662248]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWei S, Evans PC, Strijdom H, Xu S. HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy and vascular dysfunction: Effects, mechanisms and treatments. Pharmacological research. 2025 Jul:217():107812. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2025.107812. Epub 2025 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 40460975]

Gupta N, Tripathy K. Retinitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809355]

Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi Sarcoma. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521260]

Rodrigues Alves N, Barão C, Mota C, Costa L, Proença RP. Immune recovery uveitis: a focus review. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2024 Aug:262(8):2703-2712. doi: 10.1007/s00417-024-06415-y. Epub 2024 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 38381160]

Gessese T, Asrie F, Mulatie Z. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Related Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Blood and lymphatic cancer : targets and therapy. 2023:13():13-24. doi: 10.2147/BLCTT.S407086. Epub 2023 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 37275434]

Wiafe B. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus in HIV/AIDS. Community eye health. 2003:16(47):35-6 [PubMed PMID: 17491842]

Gichuhi S, Arunga S. HIV and the eye. Community eye health. 2020:33(108):76-78 [PubMed PMID: 32395031]

Acharya PK, Venugopal KC, Karimsab DP, Balasubramanya S. Ocular Manifestations in Patients with HIV Infection/AIDS who were Referred from the ART Centre, Hassan, Karnataka, India. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2012 Dec:6(10):1756-60. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2012/4738.2637. Epub 2012 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 23373045]

Kim YS, Sun HJ, Kim TH, Kang KD, Lee SJ. Ocular Manifestations of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Korean journal of ophthalmology : KJO. 2015 Aug:29(4):241-8. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2015.29.4.241. Epub 2015 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 26240508]

Shuler JD, Engstrom RE Jr, Holland GN. External ocular disease and anterior segment disorders associated with AIDS. International ophthalmology clinics. 1989 Summer:29(2):98-104 [PubMed PMID: 2541098]

Teich SA. Conjunctival vascular changes in AIDS and AIDS-related complex. American journal of ophthalmology. 1987 Mar 15:103(3 Pt 1):332-3 [PubMed PMID: 3826242]

Engstrom RE Jr, Holland GN, Hardy WD, Meiselman HJ. Hemorheologic abnormalities in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and ophthalmic microvasculopathy. American journal of ophthalmology. 1990 Feb 15:109(2):153-61 [PubMed PMID: 2301526]

Geier SA, Klauss V, Goebel FD. Ocular microangiopathic syndrome in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and its relationship to alterations in cell adhesion and in blood flow. German journal of ophthalmology. 1994 Nov:3(6):414-21 [PubMed PMID: 7866262]

Kamal S, Kaliki S, Mishra DK, Batra J, Naik MN. Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia in 200 Patients: A Case-Control Study of Immunosuppression Resulting from Human Immunodeficiency Virus versus Immunocompetency. Ophthalmology. 2015 Aug:122(8):1688-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.04.027. Epub 2015 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 26050538]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGeier SA, Libera S, Klauss V, Goebel FD. Sicca syndrome in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Ophthalmology. 1995 Sep:102(9):1319-24 [PubMed PMID: 9097769]

Bibas M, Antinori A. EBV and HIV-Related Lymphoma. Mediterranean journal of hematology and infectious diseases. 2009 Dec 29:1(2):e2009032. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2009.032. Epub 2009 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 21416008]

Chaloulis SK, Mousteris G, Tsaousis KT. Incidence and Risk Factors of Bilateral Herpetic Keratitis: 2022 Update. Tropical medicine and infectious disease. 2022 Jun 7:7(6):. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed7060092. Epub 2022 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 35736971]

Rosberger DF, Heinemann MH, Friedberg DN, Holland GN. Uveitis associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. American journal of ophthalmology. 1998 Mar:125(3):301-5 [PubMed PMID: 9512146]

Chiotan C, Radu L, Serban R, Cornăcel C, Cioboată M, Anghelie A. Posterior segment ocular manifestations of HIV/AIDS patients. Journal of medicine and life. 2014 Sep 15:7(3):399-402 [PubMed PMID: 25408764]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOlayiwola OT, Oluleye TS, Awolude OA, Adeyanju AO. Ocular and Adnexal Diseases in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Pregnant Women Attending HIV Clinics in Ibadan, Nigeria. Journal of the West African College of Surgeons. 2025 Jan-Mar:15(1):1-11. doi: 10.4103/jwas.jwas_284_22. Epub 2024 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 39735805]

Furrer H, Barloggio A, Egger M, Garweg JG, Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Retinal microangiopathy in human immunodeficiency virus infection is related to higher human immunodeficiency virus-1 load in plasma. Ophthalmology. 2003 Feb:110(2):432-6 [PubMed PMID: 12578793]

Jabs DA. Ocular manifestations of HIV infection. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1995:93():623-83 [PubMed PMID: 8719695]

Balasundaram MB, Andavar R, Palaniswamy M, Venkatapathy N. Outbreak of acquired ocular toxoplasmosis involving 248 patients. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2010 Jan:128(1):28-32. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.354. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20065213]

Kwon HJ, Son G, Lee JY, Kim JG, Kim YJ. Clinical Characteristics Associated with the Development of Cystoid Macular Edema in Patients with Cytomegalovirus Retinitis. Microorganisms. 2021 May 21:9(6):. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9061114. Epub 2021 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 34064097]

Sudharshan S, Nair N, Curi A, Banker A, Kempen JH. Human immunodeficiency virus and intraocular inflammation in the era of highly active anti retroviral therapy - An update. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Sep:68(9):1787-1798. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1248_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32823395]

Bergstrom R, Tripathy K. Acute Retinal Necrosis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262034]

Kim SJ, Equi R, Belair ML, Fine HF, Dunn JP. Long-term preservation of vision in progressive outer retinal necrosis treated with combination antiviral drugs and highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2007 Nov-Dec:15(6):425-7 [PubMed PMID: 18085485]

Geetha R, Tripathy K. Chorioretinitis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31869169]

Berger BB, Egwuagu CE, Freeman WR, Wiley CA. Miliary toxoplasmic retinitis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1993 Mar:111(3):373-6 [PubMed PMID: 8447750]

Holland GN, Engstrom RE Jr, Glasgow BJ, Berger BB, Daniels SA, Sidikaro Y, Harmon JA, Fischer DH, Boyer DS, Rao NA. Ocular toxoplasmosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. American journal of ophthalmology. 1988 Dec 15:106(6):653-67 [PubMed PMID: 3195645]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAyoade F, Joel Chandranesan AS. HIV-1–Associated Toxoplasmosis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722907]

Sudharshan S, Menia NK, Selvamuthu P, Tyagi M, Kumarasamy N, Biswas J. Ocular syphilis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Sep:68(9):1887-1893. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1070_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32823409]

Koundanya VV, Tripathy K. Syphilis Ocular Manifestations. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644383]

Sallam A, Karimaghaei S, Neuhouser AJ, Tripathy K. Ocular Tuberculosis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644729]

Chawla R, Tripathy K, Meena S, Behera AK. Subretinal Hypopyon in Presumed Tubercular Uveitis: A Report of Two Cases. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Jul-Dec:25(3-4):163-166. doi: 10.4103/meajo.MEAJO_187_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30765956]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChawla R, Venkatesh P, Tripathy K, Chaudhary S, Sharma SK. Successful Management of Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy and Multiple Choroidal Tubercles in a Patient with Miliary Tuberculosis. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2018 Apr-Jun:13(2):210-211. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_203_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29719654]

Tripathy K, Chawla R. Choroidal tuberculoma. The National medical journal of India. 2016 Mar-Apr:29(2):106 [PubMed PMID: 27586221]

Morinelli EN, Dugel PU, Riffenburgh R, Rao NA. Infectious multifocal choroiditis in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1993 Jul:100(7):1014-21 [PubMed PMID: 8321524]

Rao NA, Zimmerman PL, Boyer D, Biswas J, Causey D, Beniz J, Nichols PW. A clinical, histopathologic, and electron microscopic study of Pneumocystis carinii choroiditis. American journal of ophthalmology. 1989 Mar 15:107(3):218-28 [PubMed PMID: 2784287]

Shah SK, Adavalath S, Pai G, Pradeep V, Lodha R. Eye as a Window to Diagnosis. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2025 Jul 28:():. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000004930. Epub 2025 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 40720863]

Pescador Ruschel MA, Thapa B. Cryptococcal Meningitis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252242]

Cunningham ET, Miserocchi E, Smith JR, Gonzales JA, Zierhut M. Intraocular Lymphoma. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2021 Apr 3:29(3):425-429. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1941684. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34296968]

Steffen J, Coupland SE, Smith JR. Primary Vitreoretinal Lymphoma in HIV Infection. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2021 Apr 3:29(3):621-627. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1751856. Epub 2020 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 32453669]

Thapa S, Shrestha U. Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33620872]

Urban B, Bakunowicz-Łazarczyk A, Michalczuk M. Immune recovery uveitis: pathogenesis, clinical symptoms, and treatment. Mediators of inflammation. 2014:2014():971417. doi: 10.1155/2014/971417. Epub 2014 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 25089078]

Mwanza JC, Nyamabo LK, Tylleskär T, Plant GT. Neuro-ophthalmological disorders in HIV infected subjects with neurological manifestations. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2004 Nov:88(11):1455-9 [PubMed PMID: 15489493]

Ashizuka T, Uematsu M, Mohamed MT, Kusano M, Helmy MY, Inoue D, Kitaoka T. A case of corneal opacity caused by atovaquone administration. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2025 Mar:37():102235. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2024.102235. Epub 2024 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 39803603]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVenkatesh P, Khanduja S, Singh S, Lodha R, Kabra SK, Garg S, Vohra R. Prevalence and risk factors for developing ophthalmic manifestations in pediatric human immunodeficiency virus infection. Ophthalmology. 2013 Sep:120(9):1942-1943.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.06.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24001530]

Ikoona E, Kalyesubula I, Kawuma M. Ocular manifestations in paediatric HIV/AIDS patients in Mulago Hospital, Uganda. African health sciences. 2003 Aug:3(2):83-6 [PubMed PMID: 12913799]

Dennehy PJ, Warman R, Flynn JT, Scott GB, Mastrucci MT. Ocular manifestations in pediatric patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1989 Jul:107(7):978-82 [PubMed PMID: 2546525]

Iosub S, Bamji M, Stone RK, Gromisch DS, Wasserman E. More on human immunodeficiency virus embryopathy. Pediatrics. 1987 Oct:80(4):512-6 [PubMed PMID: 3658569]

Blokzijl ML. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in childhood. Annals of tropical paediatrics. 1988 Mar:8(1):1-17 [PubMed PMID: 2456715]

Cordero JF. Issues concerning AIDS embryopathy. American journal of diseases of children (1960). 1988 Jan:142(1):9 [PubMed PMID: 3341304]

Kempen JH, Sugar EA, Varma R, Dunn JP, Heinemann MH, Jabs DA, Lyon AT, Lewis RA, Studies of Ocular Complications of AIDS Research Group. Risk of cataract among subjects with acquired immune deficiency syndrome free of ocular opportunistic infections. Ophthalmology. 2014 Dec:121(12):2317-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.06.014. Epub 2014 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 25109932]

Pathai S, Bajillan H, Landay AL, High KP. Is HIV a model of accelerated or accentuated aging? The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2014 Jul:69(7):833-42. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt168. Epub 2013 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 24158766]

Breen EC, Sehl ME, Shih R, Langfelder P, Wang R, Horvath S, Bream JH, Duggal P, Martinson J, Wolinsky SM, Martínez-Maza O, Ramirez CM, Jamieson BD. Accelerated aging with HIV begins at the time of initial HIV infection. iScience. 2022 Jul 15:25(7):104488. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104488. Epub 2022 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 35880029]

Abdullah, Din M, Waris A, Khan M, Ali S, Muhammad R, Salman M. The contemporary immunoassays for HIV diagnosis: a concise overview. Asian biomedicine : research, reviews and news. 2023 Feb:17(1):3-12. doi: 10.2478/abm-2023-0038. Epub 2023 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 37551202]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLangford SE, Ananworanich J, Cooper DA. Predictors of disease progression in HIV infection: a review. AIDS research and therapy. 2007 May 14:4():11 [PubMed PMID: 17502001]

. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 1992 Dec 18:41(RR-17):1-19 [PubMed PMID: 1361652]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKalogeropoulos D, Afshar F, Kalogeropoulos C, Vartholomatos G, Lotery AJ. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in acute retinal necrosis; an update. Eye (London, England). 2024 Jul:38(10):1816-1826. doi: 10.1038/s41433-024-03028-x. Epub 2024 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 38519714]

Kaya M, Öner FH, Lebe B, Özkal S, Men S, Saatci AO. Challenges in the Diagnosis of Intraocular Lymphoma. Turkish journal of ophthalmology. 2021 Oct 26:51(5):317-325. doi: 10.4274/tjo.galenos.2021.50607. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34702874]

Swinkels HM, Nguyen AD, Gulick PG. HIV and AIDS. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521281]

Kemnic TR, Gulick PG. HIV Antiretroviral Therapy. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020680]

Minor M, Payne E. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491711]

Hebert AA, Bhatia N, Del Rosso JQ. Molluscum Contagiosum: Epidemiology, Considerations, Treatment Options, and Therapeutic Gaps. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology. 2023 Aug:16(8 Suppl 1):S4-S11 [PubMed PMID: 37636018]

Badri T, Gandhi GR. Molluscum Contagiosum. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722927]

Radhakrishnan N, Smit D, Venkatesh Prajna N, S R R. Corneal Involvement in HIV-infected Individuals. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2021 Aug 18:29(6):1177-1182. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1887283. Epub 2021 Jul 7 [PubMed PMID: 34232799]

Gurnani B, Kim J, Tripathy K, Mahabadi N, Edens MA. Iritis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613659]

Gupta M, Shorman M. Cytomegalovirus Infections. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083720]

Stokkermans TJ, Havens SJ. Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29630234]

Tudor ME, Al Aboud AM, Leslie SW, Gossman W. Syphilis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521201]

White PL, Price JS, Backx M. Therapy and Management of Pneumocystis jirovecii Infection. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Nov 22:4(4):. doi: 10.3390/jof4040127. Epub 2018 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 30469526]

Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, Baddley JW, McKinsey DS, Loyd JE, Kauffman CA, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007 Oct 1:45(7):807-25 [PubMed PMID: 17806045]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcKinsey DS. Treatment and Prevention of Histoplasmosis in Adults Living with HIV. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 May 28:7(6):. doi: 10.3390/jof7060429. Epub 2021 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 34071599]

Gordon LK, Danesh-Meyer H. Neuro-Ophthalmic Manifestations of HIV Infection. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2020 Oct 2:28(7):1085-1093. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2019.1704024. Epub 2020 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 31961200]

Ramaswami R, Lurain K, Yarchoan R. Oncologic Treatment of HIV-Associated Kaposi Sarcoma 40 Years on. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2022 Jan 20:40(3):294-306. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02040. Epub 2021 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 34890242]

Pereira-Da Silva MV, Di Nicola ML, Altomare F, Xu W, Tsang R, Laperriere N, Krema H. Radiation therapy for primary orbital and ocular adnexal lymphoma. Clinical and translational radiation oncology. 2023 Jan:38():15-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2022.10.001. Epub 2022 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 36353653]

Abdi F, Mohammadi SS, Falavarjani KG. Intravitreal Methotrexate. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2021 Oct-Dec:16(4):657-669. doi: 10.18502/jovr.v16i4.9756. Epub 2021 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 34840688]

Gichuhi S, Irlam JH. Interventions for squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva in HIV-infected individuals. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Feb 28:2013(2):CD005643. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005643.pub3. Epub 2013 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 23450564]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBanker AS. Posterior segment manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2008 Sep-Oct:56(5):377-83 [PubMed PMID: 18711265]

Ausayakhun S, Keenan JD, Ausayakhun S, Jirawison C, Khouri CM, Skalet AH, Heiden D, Holland GN, Margolis TP. Clinical features of newly diagnosed cytomegalovirus retinitis in northern Thailand. American journal of ophthalmology. 2012 May:153(5):923-931.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.012. Epub 2012 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 22265148]

Muthiah MN, Michaelides M, Child CS, Mitchell SM. Acute retinal necrosis: a national population-based study to assess the incidence, methods of diagnosis, treatment strategies and outcomes in the UK. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2007 Nov:91(11):1452-5 [PubMed PMID: 17504853]

Batisse D, Eliaszewicz M, Zazoun L, Baudrimont M, Pialoux G, Dupont B. Acute retinal necrosis in the course of AIDS: study of 26 cases. AIDS (London, England). 1996 Jan:10(1):55-60 [PubMed PMID: 8924252]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEngstrom RE Jr, Holland GN, Margolis TP, Muccioli C, Lindley JI, Belfort R Jr, Holland SP, Johnston WH, Wolitz RA, Kreiger AE. The progressive outer retinal necrosis syndrome. A variant of necrotizing herpetic retinopathy in patients with AIDS. Ophthalmology. 1994 Sep:101(9):1488-502 [PubMed PMID: 8090452]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSittivarakul W, Treerutpun W, Tungsattayathitthan U. Clinical characteristics, visual acuity outcomes, and factors associated with loss of vision among patients with active ocular toxoplasmosis: A retrospective study in a Thai tertiary center. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2024 Jun:18(6):e0012232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0012232. Epub 2024 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 38843299]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGagliuso DJ, Teich SA, Friedman AH, Orellana J. Ocular toxoplasmosis in AIDS patients. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1990:88():63-86; discussion 86-8 [PubMed PMID: 2095034]

Shiezadeh E, Hosseini SM, Bakhtiari E, Mojarrad A, Motamed Shariati M. Clinical characteristics and management outcomes of acute retinal necrosis. Scientific reports. 2023 Oct 7:13(1):16927. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-44310-4. Epub 2023 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 37805622]

Smith JR, Cunningham ET Jr. Atypical presentations of ocular toxoplasmosis. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2002 Dec:13(6):387-92 [PubMed PMID: 12441842]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceButler NJ, Furtado JM, Winthrop KL, Smith JR. Ocular toxoplasmosis II: clinical features, pathology and management. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2013 Jan-Feb:41(1):95-108. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2012.02838.x. Epub 2012 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 22712598]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParekh P, Oldfield EC, Marik PE. Progressive outer retinal necrosis: a missed diagnosis and a blind, young woman. BMJ case reports. 2013 Apr 22:2013():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009333. Epub 2013 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 23608868]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGore DM, Gore SK, Visser L. Progressive outer retinal necrosis: outcomes in the intravitreal era. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2012 Jun:130(6):700-6. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.2622. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22801826]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceInvernizzi A, Agarwal AK, Ravera V, Mapelli C, Riva A, Staurenghi G, McCluskey PJ, Viola F. Comparing optical coherence tomography findings in different aetiologies of infectious necrotising retinitis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Apr:102(4):433-437. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310210. Epub 2017 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 28765144]

Kelgaonkar A, Jadhav V, Patel A, Basu S, Pathengay A. Clinical characteristics, imaging features, and fate of punctate outer retinal toxoplasmosis lesions in immunocompetent cases of ocular toxoplasmosis. Taiwan journal of ophthalmology. 2025 Apr-Jun:15(2):270-276. doi: 10.4103/tjo.TJO-D-25-00011. Epub 2025 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 40584191]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChawla R, Tripathy K, Sharma YR, Venkatesh P, Vohra R. Periarterial Plaques (Kyrieleis' Arteriolitis) in a Case of Bilateral Acute Retinal Necrosis. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2017:32(2):251-252. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2015.1045153. Epub 2015 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 26161821]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTeng Siew T, Mohamad SA, Sudarno R, Md Said H. Atypical Ocular Toxoplasmosis With Remote Vasculitis and Kyrieleis Plaques. Cureus. 2024 Jan:16(1):e52756. doi: 10.7759/cureus.52756. Epub 2024 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 38389616]

Kovačević-Pavićević D, Radosavljević A, Ilić A, Kovačević I, Djurković-Djaković O. Clinical pattern of ocular toxoplasmosis treated in a referral centre in Serbia. Eye (London, England). 2012 May:26(5):723-8. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.20. Epub 2012 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 22361847]

Kempen JH, Jabs DA, Dunn JP, West SK, Tonascia J. Retinal detachment risk in cytomegalovirus retinitis related to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2001 Jan:119(1):33-40 [PubMed PMID: 11146724]

Ude IN, Yeh S, Shantha JG. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in the highly active anti-retroviral therapy era. Annals of eye science. 2022 Mar:7():. pii: 5. doi: 10.21037/aes-21-18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35498636]

Zhao XY, Meng LH, Zhang WF, Wang DY, Chen YX. RETINAL DETACHMENT AFTER ACUTE RETINAL NECROSIS AND THE EFFICACIES OF DIFFERENT INTERVENTIONS: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2021 May 1:41(5):965-978. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002971. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32932382]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOrmerod LD, Larkin JA, Margo CA, Pavan PR, Menosky MM, Haight DO, Nadler JP, Yangco BG, Friedman SM, Schwartz R, Sinnott JT. Rapidly progressive herpetic retinal necrosis: a blinding disease characteristic of advanced AIDS. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1998 Jan:26(1):34-45; discussion 46-7 [PubMed PMID: 9455507]

Amaral DC, Lane M, Aguiar EHC, Marques GN, Cavassani LV, Rodrigues MPM, Alves MR, Manso JEF, Monteiro MLR, Louzada RN. Surgical management of retinal detachment and macular holes secondary to ocular toxoplasmosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of retina and vitreous. 2024 Feb 29:10(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s40942-024-00540-w. Epub 2024 Feb 29 [PubMed PMID: 38424638]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJustiz Vaillant AA, Naik R. HIV-1–Associated Opportunistic Infections. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969609]

Yuan M, Young LH. Immune Recovery Uveitis: A Comprehensive Review. International ophthalmology clinics. 2025 Jul 1:65(3):142-151. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000565. Epub 2025 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 40601519]

Waymack JR, Sundareshan V. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725978]

Jabs DA, Van Natta ML, Thorne JE, Weinberg DV, Meredith TA, Kuppermann BD, Sepkowitz K, Li HK, Studies of Ocular Complications of AIDS Research Group. Course of cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: 2. Second eye involvement and retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 2004 Dec:111(12):2232-9 [PubMed PMID: 15582079]

Wong JX, Wong EP, Teoh SC. Outcomes of cytomegalovirus retinitis-related retinal detachment surgery in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients in an Asian population. BMC ophthalmology. 2014 Nov 27:14():150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-150. Epub 2014 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 25429876]

Sittivarakul W, Prapakornkovit V, Jirarattanasopa P, Bhurayanontachai P, Ratanasukon M. Surgical outcomes and prognostic factors following vitrectomy in acquired immune deficiency syndrome patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis-related retinal detachment. Medicine. 2020 Oct 23:99(43):e22889. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022889. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33120835]