Introduction

Thrombophlebitis is inflammation of a vein with an associated thrombus. Migratory thrombophlebitis, or thrombophlebitis migrans, is characterized by sequential involvement: one vein segment becomes inflamed, improves, and is followed by inflammation of other segments. See Image. Migratory Thrombophlebitis. Occasionally, several veins in different locations may be involved simultaneously, and both superficial and deep veins may be affected.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis is associated with systemic diseases such as hypertension,[1] Buerger disease (thrombophlebitis obliterans),[2][3] hypercoagulable conditions such as deficiencies of protein C and lupus anticoagulant,[4] factor XII deficiency,[5] inflammatory bowel disease,[6] Behçet disease,[7] and pancreatic cancer. Case reports describe thrombophlebitis in individuals who smoke cannabis and in a patient with Q fever.[8][9] Armand Trousseau first described the association of superficial migratory thrombophlebitis with visceral malignancy in 1865. Trousseau syndrome is characterized by unexplained thrombotic events that are due to an occult visceral malignancy or occur concomitantly with cancer.[10][11] In patients with cancer, deep veins are also involved, and pulmonary embolism is a frequent complication.[12] Unusual venous sites, such as the upper extremities, trunk, and chest wall, may also be involved.[11]

Predisposing factors for migratory thrombophlebitis, particularly Trousseau syndrome, include older age, obesity, surgery, immobility, history of thrombosis, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, hypertension, and other cardiovascular conditions. Specific chemotherapeutic agents and their toxicities are treatment-related risk factors. Lastly, the hypercoagulable state associated with cancer results from the release of inflammatory cytokines, tissue factor, and thrombin receptor activators, as well as their interactions with the endothelium.[13] Inflammation plays a role in thrombosis in both cancer and infection, mediated by the actions of neutrophils, monocytes, and platelets. This mechanism underlies the development of several novel biomarkers that aid in the more accurate diagnosis of thrombosis. [14][15]

Epidemiology

Idiopathic thrombophlebitis migrans typically occurs between ages 25 and 50 years, with a mean age of approximately 40 years. Men are affected 3 times more often than women, and the condition typically occurs in otherwise healthy adults.[10][16] A wide range of cancers is associated with migratory thrombophlebitis, although the frequencies of cancer types associated with migratory thrombophlebitis vary. Some studies report a high incidence of thrombophlebitis associated with pancreatic body and tail carcinomas. In contrast, others report a higher association with lung adenocarcinomas in men and reproductive tract malignancies in women.[10][17][18] Associations are often reported with gastrointestinal (particularly pancreatic and gastric), lung, and urogenital cancers.[19]

Pathophysiology

Phlebitis in association with cancer is distinctive, and its pathogenesis is not well understood. Studies describe overlapping mechanisms in Trousseau syndrome.[11] Early reports noted that Trousseau syndrome commonly occurred in mucin-producing adenocarcinomas; however, associations with other malignancies are now recognized.[19] Mucins are highly glycosylated glycoproteins secreted by epithelial cells. In carcinomas, mucins are aberrantly glycosylated and are inappropriately secreted into the blood; the liver metabolizes most of these mucins, while a small fraction remains. These mucins bind to L-selectin adhesion molecules expressed on leukocytes, P-selectin adhesion molecules expressed on platelets, and endothelial cells, promoting the formation of platelet-rich microthrombi.[19]

Tissue Factor (TF) is another proposed driver of Trousseau syndrome. Cancer cells express increased levels of highly procoagulant TF.[20] Inflammatory cytokines produced by cancer cells can also induce TF expression in vascular cells, where it is not normally expressed. Additionally, cancer cells also induce monocytes and macrophages to release TF. TF promotes the conversion of factor VII to factor VIIa, thereby activating the extrinsic pathway of the coagulation cascade.[21][22][23] Cancer procoagulant, also called cysteine proteinase, is expressed by both malignant and normal cells (except in fetal tissue) and functions to facilitate the conversion of factor X to factor Xa.[24] Hypoxia also promotes coagulation through the upregulation of TF and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1.[25]

Histopathology

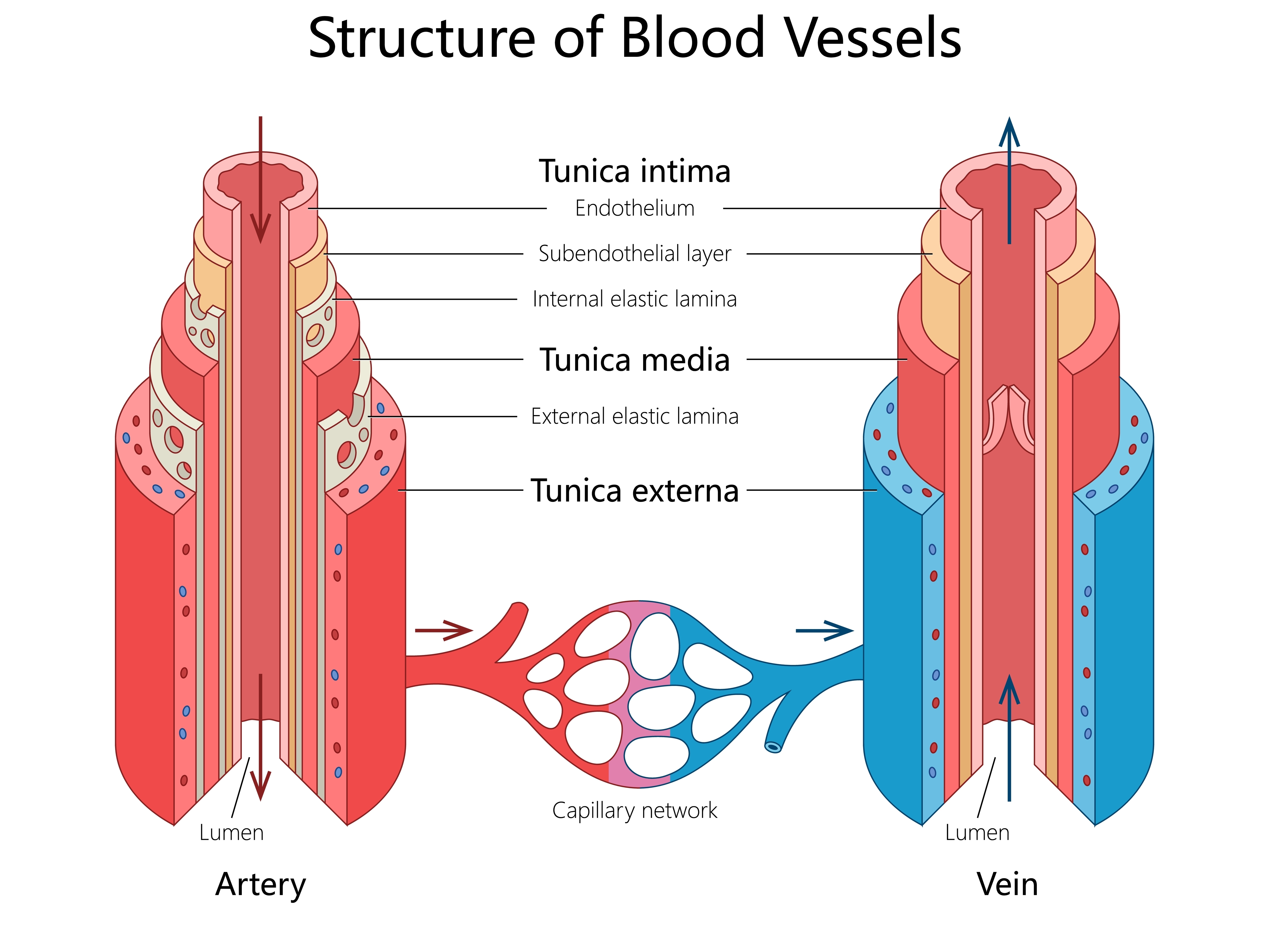

Inflammatory infiltrates invade the vascular wall, including neutrophils, eosinophils, histiocytes, lymphocytes, and giant cells. An organized thrombus initially forms within the lumen, which is then recanalized and fibrosed later. The absence of an internal elastic lamina is made evident by orcein staining.[26] Polyarteritis nodosa, a necrotizing vasculitis of medium-sized arteries, is the principal histopathologic differential diagnosis for superficial migratory thrombophlebitis.

This autoimmune condition can be distinguished by its arterial features: relatively thick walls, a smaller luminal diameter relative to wall thickness, and a well-defined internal elastic lamina.[27] See Image. Layers of the Arterial and Venous Walls. In Trousseau syndrome, the affected vein shows no tumor or tumor emboli invasion, and a mild inflammatory reaction is typically present.[19] Buerger disease (thromboangiitis obliterans) can be distinguished from Trousseau syndrome by characteristic inflammation and thrombosis of small to medium-sized arteries and veins, as well as giant cells and microabscesses within the thrombi.[28]

History and Physical

Given the frequent association of migratory thrombophlebitis with systemic disease, obtaining a detailed history to identify potential underlying disorders is essential. A history of hypertension, smoking tobacco or cannabis, travel history, personal and family history of cancer, hypercoagulable disorders, and autoimmune disorders may identify the etiology. To evaluate the migratory nature of the condition, patients should be questioned about prior episodes and the location of the involved veins.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with superficial thrombophlebitis present with pain, erythema, and induration along the course of a superficial vein. A tender, cordlike, nodular segment is often palpable due to the thrombus, and the patient may also be febrile. Assessing high-risk individuals for signs and symptoms of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, including those older than 60 years, men, individuals with systemic infections, and those with bilateral superficial vein thromboses, is vital. Mondor disease is superficial thrombophlebitis of the epigastric, thoracoepigastric, or lateral thoracic veins, presenting as painful, indurated, erythematous cords.[29] Thrombophlebitis may also occur in the axilla, penis, and the inguinal region.[30]

Evaluation

Superficial thrombophlebitis is primarily a clinical diagnosis. Patients typically present with pain and erythema at the involved site. On palpation, the vein is firm and tender. Brown discoloration or hyperpigmentation from hemosiderin deposition may appear over previously affected veins. Extensive extremity edema may indicate the presence of a deep vein thrombosis (DVT).[31][32]

Indications for Duplex Ultrasonography

Duplex ultrasonography is indicated for patients with pain along the course of superficial veins, but without physical examination, findings suggest thrombophlebitis. However, patients with obesity have superficial veins several centimeters below the skin surface, so even superficial thrombophlebitis may present with normal-appearing skin. These patients may have superficial or deep venous involvement, requiring a duplex ultrasonography to evaluate for DVT.[33] Superficial venous thrombosis involving the great saphenous and small saphenous veins is at high risk of progression to DVT. If the patient has thrombophlebitis involving these veins, duplex ultrasonography should be performed to evaluate the extent of the thrombus.[34][35] Patients with significant extremity edema should also have a duplex ultrasonography to evaluate for DVT. Furthermore, the diagnosis of migratory thrombophlebitis may be the initial presentation of an occult malignancy or other systemic disorder.[35] Cancer can manifest months to years after superficial migratory thrombophlebitis is diagnosed. Upon diagnosis, patients with migratory thrombophlebitis should undergo evaluation for an underlying malignancy and other systemic disorders.

A comprehensive evaluation includes:

- A comprehensive history to evaluate for symptoms and signs of cancer

- A thorough physical examination, including a digital rectal examination, fecal occult blood testing, and pelvic examination in women

- Laboratory testing: Complete blood count with peripheral smear, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, urinalysis, tumor markers, autoimmune biomarkers, and hypercoagulability studies

- Chest radiograph

- Computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis

- Age-appropriate cancer screening, including mammography and a Papanicolaou test in women, and upper and lower gastrointestinal tract evaluation if warranted

Treatment / Management

The treatment goals are to relieve local symptoms and prevent thrombus propagation. Supportive care includes elevating the affected extremity, using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, applying a warm or cold compress, wearing compression stockings, and increasing ambulation. Supportive care is indicated in patients with superficial thrombophlebitis involving a vein segment measuring less than 5 cm, a thrombus site remote from the saphenofemoral or saphenopopliteal junction, and no risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Typically, these patients should be reevaluated in 7 to 10 days, unless symptoms worsen. If symptoms progress or do not improve, duplex ultrasonography should be obtained to exclude DVT.

Anticoagulation Indications:

- Evidence of thrombus propagation

- Thrombus length greater than 5 cm

- Thrombus 5 cm from the saphenofemoral junction or saphenopopliteal junction

- Concomitant DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE)

The choice of anticoagulation agent, dose, and duration of treatment is controversial. In patients with superficial venous thrombosis, an intermediate subcutaneous dose of low-molecular-weight heparin, such as enoxaparin 40 mg daily, dalteparin 5000 units every 12 hours, subcutaneous fondaparinux 2.5 mg daily, or oral rivaroxaban 10 mg daily is suggested for 45 days.[36][37][38][39] A longer course of anticoagulation is recommended for patients with DVT or PE. In patients with contraindications to anticoagulation, the recommendation is to ligate the saphenous vein at a saphenofemoral or saphenopopliteal junction. In patients with Trousseau syndrome, heparin is the preferred method of anticoagulation. Heparin inactivates thrombin and activates factor Xa, interrupting secondary platelet activation and fluid-phase thrombosis.[11][23][40] Migratory thrombophlebitis may be refractory to anticoagulation in patients with cancer, resulting in the progression of thrombus and potentially recurrent pulmonary embolism.[18] Case reports describe improvements in phlebitis and a reduction in thrombosis after surgical removal of the underlying malignancy.[41][42] Finally, the clinician should strongly recommend smoking cessation in patients with Buerger disease.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of superficial migratory thrombophlebitis includes cellulitis, lymphangitis, erythema nodosum, nodular vasculitis, and polyarteritis nodosa.[12][26] Palpable, cordlike nodules and a linear, serpiginous pattern of purpura are distinguishing features of superficial migratory thrombophlebitis.[43]

Prognosis

The prognosis for migratory thrombophlebitis depends on the etiology. For thrombophlebitis associated with malignancies, the prognosis is poor, with a 1-year survival of only 12%. For this reason, immediate treatment is indicated at diagnosis.[44] In contrast, benign etiologies generally have a good prognosis. However, these patients may develop postphlebitic (postthrombotic) syndrome with manifestations of chronic venous insufficiency.[45][46] See Image Chronic Venous Insufficiency. Patients require compression stockings for life to prevent postphlebitic syndrome. Those who have a thrombus need anticoagulation therapy for 3 to 9 months. Untreated disease may lead to PE, which can be fatal.

Complications

A common complication is the extension of a thrombus, which can lead to DVT and PE, with the risk as high as 18%.[32][34][47] Unusual venous sites, such as the neck and abdominal viscera, may also be involved.[16] Postthrombotic (postphlebitic) syndrome develops and leads to manifestations of chronic venous insufficiency, including varicose veins, hyperpigmentation, pitting edema, and venous ulcers.[45][46][48] A regimen of compression stockings, ulcer compression, and exercise training can effectively manage postphlebitic syndrome. The role of endovascular intervention is unclear, although it may be considered for severe postphlebitic syndrome.[49]

Consultations

In patients with migratory thrombophlebitis, consulting a hematology oncology clinician is recommended. In patients requiring surgical ligation, a consultation with a vascular surgeon is the recommended course of action.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Educating patients regarding the migratory and recurrent nature of thrombophlebitis and encouraging them to participate in the evaluation for underlying systemic disorders and malignancies is crucial.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of migratory thrombophlebitis require an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals, including primary care clinicians, dermatologists, pharmacists, vascular surgeons, nurses, sonographers, and hematologist-oncologists, who collaborate to optimize patient outcomes. Most patients with thrombophlebitis initially present to the primary care clinician. These clinicians should perform a comprehensive history and physical examination to determine the need for a duplex ultrasonography to evaluate for DVT. Care coordination and continuity of care with primary care clinicians and nurses are crucial for these patients.

If the phlebitis is recurrent and migratory, clinicians should consider evaluating for an underlying malignancy. A referral to internal medicine or oncology is recommended. While the patient is being assessed, pharmacists may educate the patient on medication compliance if the clinician discovers a DVT. Pharmacist verification of dosing and administration of anticoagulant therapy is critical, and any concerns should be reported to the clinician. Additionally, patient education on wearing compression stockings is crucial to prevent postphlebitic syndrome. Each follow-up visit should evaluate therapeutic results. Even when the primary cause of thrombophlebitis is diagnosed and treated, the affected veins may also require treatment. Failing to administer anticoagulation for DVT increases the risk of PE. The interprofessional healthcare team must collaborate and communicate effectively to achieve optimal outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Laguna C, Pérez-Ferriols A, Alegre V. Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis in a hypertensive patient: response to antihypertensive therapy. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2008 Mar:22(3):383-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02337.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18269615]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePeña-penabad C, Martínez W, del Pozo J, García-Silva J, Yebra MT, Fonseca E. Guess what! Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger's disease). European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2000 Jul-Aug:10(5):405-6 [PubMed PMID: 11023339]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVILANOVA X, MORAGAS JM. [Thrombophlebitis migrans: first apparent sign of thromboangiitis obliterans]. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 1952 Jun:43(9):812-3 [PubMed PMID: 12985470]

Blum F, Gilkeson G, Greenberg C, Murray J. Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis and the lupus anticoagulant. International journal of dermatology. 1990 Apr:29(3):190-2 [PubMed PMID: 2110553]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSamlaska CP, James WD, Simel DL. Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis and factor XII deficiency. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1990 May:22(5 Pt 2):939-43 [PubMed PMID: 2110579]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIyer SK, Handler LJ, Johnston JS. Thrombophlebitis migrans in association with ulcerative colitis. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1981 Oct:73(10):987-9 [PubMed PMID: 7310913]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChajek T, Fainaru M. Behçet's disease. Report of 41 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine. 1975 May:54(3):179-96 [PubMed PMID: 1095889]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFernández Guerrero ML, Rivas P, García Delgado R. Migratory thrombophlebitis and acute Q fever. Emerging infectious diseases. 2004 Mar:10(3):546-7 [PubMed PMID: 15116709]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee C, Moll S. Migratory superficial thrombophlebitis in a cannabis smoker. Circulation. 2014 Jul 8:130(2):214-5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009935. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25001627]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGROSS FB Jr, JAEHNING DG, COKER WG. The association of migratory thrombophlebitis with carcinoma. North Carolina medical journal. 1951 Mar:12(3):97-101 [PubMed PMID: 14827321]

Varki A. Trousseau's syndrome: multiple definitions and multiple mechanisms. Blood. 2007 Sep 15:110(6):1723-9 [PubMed PMID: 17496204]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLesher JL Jr. Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis. Cutis. 1991 Mar:47(3):177-80 [PubMed PMID: 2022126]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMorales Eslava BA, Becerra Bello J. Trousseau's Syndrome: A Paraneoplastic Complication. Cureus. 2024 Aug:16(8):e66969. doi: 10.7759/cureus.66969. Epub 2024 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 39156994]

Kaiser R, Gold C, Stark K. Recent Advances in Immunothrombosis and Thromboinflammation. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2025 May 1:():. doi: 10.1055/a-2523-1821. Epub 2025 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 40311639]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMurariu-Gligor EE, Mureșan S, Cotoi OS. From Cell Interactions to Bedside Practice: Complete Blood Count-Derived Biomarkers with Diagnostic and Prognostic Potential in Venous Thromboembolism. Journal of clinical medicine. 2025 Jan 2:14(1):. doi: 10.3390/jcm14010205. Epub 2025 Jan 2 [PubMed PMID: 39797287]

FISCHER EH. Thrombophlebitis migrans. The Journal of the Kansas Medical Society. 1946 Jun:47():245-9 [PubMed PMID: 20986053]

LIEBERMAN JS, BORRERO J, URDANETA E, WRIGHT IS. Thrombophlebitis and cancer. JAMA. 1961 Aug 26:177():542-5 [PubMed PMID: 13762005]

SMITH EK. MULTIPLE MIGRATORY THROMBOPHLEBITIS IN MALIGNANT DISEASE. Guy's Hospital reports. 1964:113():91-5 [PubMed PMID: 14157987]

Oster MW. Thrombophlebitis and cancer. A review. Angiology. 1976 Oct:27(10):557-67 [PubMed PMID: 802883]

Geddings JE, Mackman N. Tumor-derived tissue factor-positive microparticles and venous thrombosis in cancer patients. Blood. 2013 Sep 12:122(11):1873-80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-460139. Epub 2013 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 23798713]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCallander NS, Varki N, Rao LV. Immunohistochemical identification of tissue factor in solid tumors. Cancer. 1992 Sep 1:70(5):1194-201 [PubMed PMID: 1381270]

Van Dreden P, Εlalamy Ι, Gerotziafas GT. The Role of Tissue Factor in Cancer-Related Hypercoagulability, Tumor Growth, Angiogenesis and Metastasis and Future Therapeutic Strategies. Critical reviews in oncogenesis. 2017:22(3-4):219-248. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2018024859. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29604900]

Rao LV. Tissue factor as a tumor procoagulant. Cancer metastasis reviews. 1992 Nov:11(3-4):249-66 [PubMed PMID: 1423817]

Falanga A, Gordon SG. Isolation and characterization of cancer procoagulant: a cysteine proteinase from malignant tissue. Biochemistry. 1985 Sep 24:24(20):5558-67 [PubMed PMID: 3935163]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDenko NC, Giaccia AJ. Tumor hypoxia, the physiological link between Trousseau's syndrome (carcinoma-induced coagulopathy) and metastasis. Cancer research. 2001 Feb 1:61(3):795-8 [PubMed PMID: 11221857]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLaguna C, Alegre V, Pérez A. [Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis: a clinical and histologic review of 8 cases]. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2008 Jun:99(5):390-5 [PubMed PMID: 18501171]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen KR. The misdiagnosis of superficial thrombophlebitis as cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: features of the internal elastic lamina and the compact concentric muscular layer as diagnostic pitfalls. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2010 Oct:32(7):688-93. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181d7759d. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20647909]

Tanaka K. Pathology and pathogenesis of Buerger's disease. International journal of cardiology. 1998 Oct 1:66 Suppl 1():S237-42 [PubMed PMID: 9951825]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCrisan D, Badea R, Crisan M. Thrombophlebitis of the lateral chest wall (Mondor's disease). Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2014 Jan-Feb:80(1):96. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.125512. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24448146]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceÖztürk H. Penile Mondor's disease. Basic and clinical andrology. 2014:24():5. doi: 10.1186/2051-4190-24-5. Epub 2014 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 25780580]

Maddox RP, Seupaul RA. What Is the Most Effective Treatment of Superficial Thrombophlebitis? Annals of emergency medicine. 2016 May:67(5):671-2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.10.018. Epub 2015 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 26707361]

Nasr H, Scriven JM. Superficial thrombophlebitis (superficial venous thrombosis). BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2015 Jun 22:350():h2039. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2039. Epub 2015 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 26099257]

Blumenberg RM, Barton E, Gelfand ML, Skudder P, Brennan J. Occult deep venous thrombosis complicating superficial thrombophlebitis. Journal of vascular surgery. 1998 Feb:27(2):338-43 [PubMed PMID: 9510288]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLutter KS, Kerr TM, Roedersheimer LR, Lohr JM, Sampson MG, Cranley JJ. Superficial thrombophlebitis diagnosed by duplex scanning. Surgery. 1991 Jul:110(1):42-6 [PubMed PMID: 1866693]

Skillman JJ, Kent KC, Porter DH, Kim D. Simultaneous occurrence of superficial and deep thrombophlebitis in the lower extremity. Journal of vascular surgery. 1990 Jun:11(6):818-23; discussion 823-4 [PubMed PMID: 2193177]

Decousus H, Prandoni P, Mismetti P, Bauersachs RM, Boda Z, Brenner B, Laporte S, Matyas L, Middeldorp S, Sokurenko G, Leizorovicz A, CALISTO Study Group. Fondaparinux for the treatment of superficial-vein thrombosis in the legs. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Sep 23:363(13):1222-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912072. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20860504]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDi Nisio M, Wichers IM, Middeldorp S. Treatment for superficial thrombophlebitis of the leg. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Feb 25:2(2):CD004982. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004982.pub6. Epub 2018 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 29478266]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDuffett L, Kearon C, Rodger M, Carrier M. Treatment of Superficial Vein Thrombosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2019 Mar:119(3):479-489. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1677793. Epub 2019 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 30716777]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWichers IM, Di Nisio M, Büller HR, Middeldorp S. Treatment of superficial vein thrombosis to prevent deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Haematologica. 2005 May:90(5):672-7 [PubMed PMID: 15921382]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohnson AC, Kurtides ES. Migratory thrombophlebitis. Heparin sodium vs. warfarin sodium therapy. IMJ. Illinois medical journal. 1967 Jan:131(1):54-6 [PubMed PMID: 4382849]

WOMACK WS, CASTELLANO CJ. Migratory thrombophlebitis associated with ovarian carcinoma. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1952 Feb:63(2):467-9 [PubMed PMID: 14894567]

WOOLLING KR, SHICK RM. Thrombophlebitis: a possible clue to cryptic malignant lesions. Proceedings of the staff meetings. Mayo Clinic. 1956 Apr 18:31(8):227-33 [PubMed PMID: 13323038]

Tian F, Mazurek KR, Malinak RN, Dean SM, Kaffenberger BH. Pseudocellulitis Need Not be Benign: Three Cases of Superficial Migratory Thrombophlebitis with "Negative" Venous Duplex Ultrasonography. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology. 2017 Dec:10(12):49-51 [PubMed PMID: 29399267]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu XJ, Liu YX, Zhang NY. A case report of Trousseau syndrome. Medicine. 2023 Jul 28:102(30):e34449. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000034449. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37505132]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCalderon Martinez E, Garza Morales R. Postthrombotic Syndrome. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 38861628]

Patel SK, Surowiec SM. Venous Insufficiency. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613694]

Chengelis DL, Bendick PJ, Glover JL, Brown OW, Ranval TJ. Progression of superficial venous thrombosis to deep vein thrombosis. Journal of vascular surgery. 1996 Nov:24(5):745-9 [PubMed PMID: 8918318]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAzar J, Rao A, Oropallo A. Chronic venous insufficiency: a comprehensive review of management. Journal of wound care. 2022 Jun 2:31(6):510-519. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2022.31.6.510. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35678787]

Cosmi B, Stanek A, Kozak M, Wennberg PW, Kolluri R, Righini M, Poredos P, Lichtenberg M, Catalano M, De Marchi S, Farkas K, Gresele P, Klein-Wegel P, Lessiani G, Marschang P, Pecsvarady Z, Prior M, Puskas A, Szuba A. The Post-thrombotic Syndrome-Prevention and Treatment: VAS-European Independent Foundation in Angiology/Vascular Medicine Position Paper. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2022:9():762443. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.762443. Epub 2022 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 35282358]