Introduction

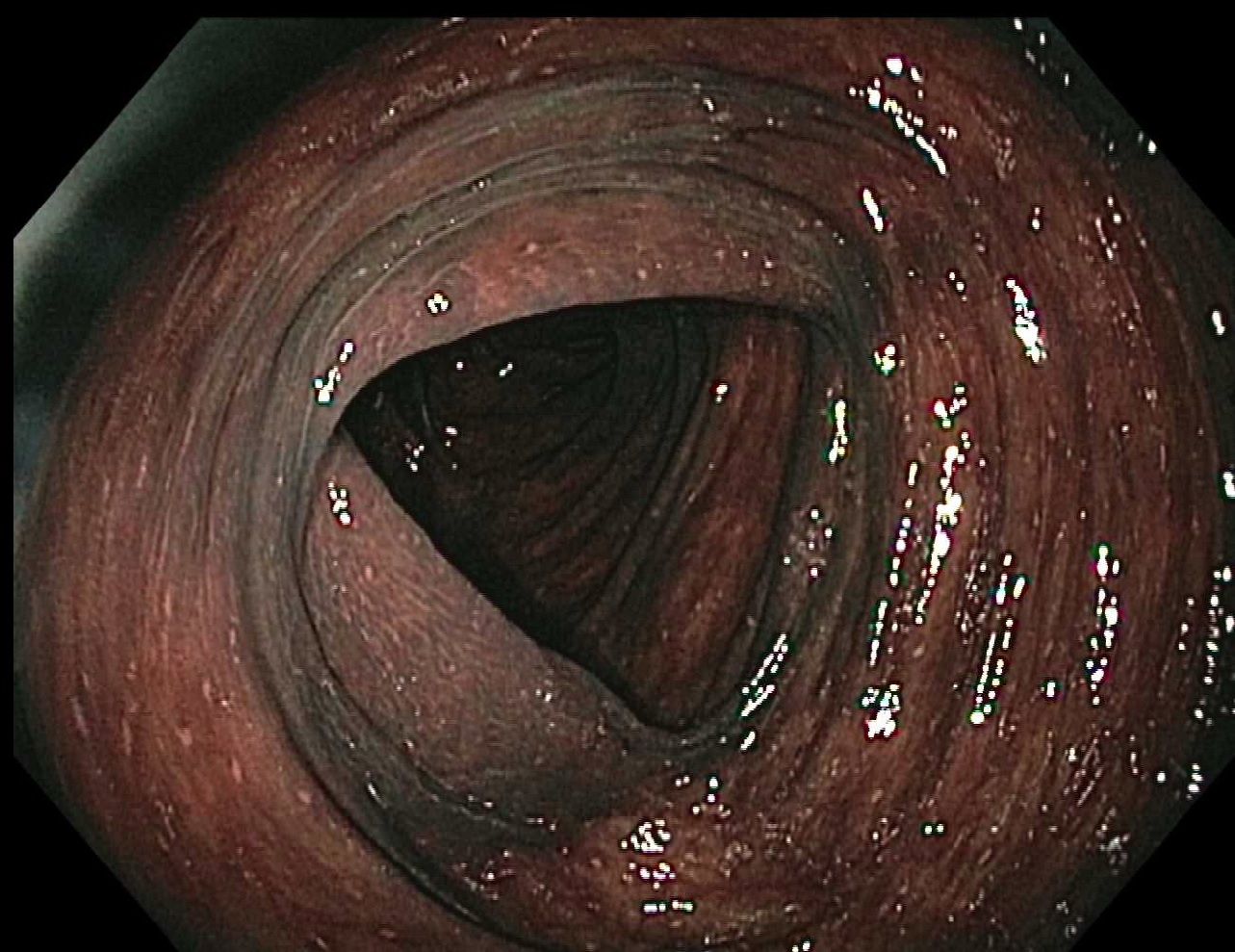

Melanosis coli is a condition associated with lipofuscin deposition (not melanin as the name might imply, and hence, alternatively termed "pseudomelanosis") in the lamina propria of the large intestines. This phenomenon was first described by Andral and Cruveilhier in 1830. Historically, laxatives, primarily from plant-based anthraquinones (ie, senna, rhubarb, cascara, and aloe), are the main culprits. As these laxative supplements pass through the colon, they become active and cause cell death and apoptosis in the lining of the colon, eventually causing dark pigmentation of the colon (see Image. Melanosis Coli). Diagnosis is typically made by colonoscopy. Discontinuing laxative use usually leads to the resolution of melanosis coli. Melanosis coli is not associated with an increased risk of colon cancer.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Melanosis coli is mainly associated with chronic laxative use, particularly anthraquinone-containing compounds. Senna glycoside (senna) is the common causative laxative. Other anthraquinones used in herbal remedies include rhubarb, cascara, and aloe. As the laxative travels down the intestinal tract, it remains in the inactive form until it reaches the large intestine. Once in the large intestine, the molecules transform into active forms, leading to cell damage and the apoptosis of colonic epithelial cells. As these cells undergo apoptosis, they create a dark pigment called lipofuscin. These apoptotic bodies containing lipofuscin are phagocytosed by macrophages, leading to darkened pigmentation of the colon wall. Melanosis coli can occur within only a few months of chronic laxative use.

In a case series of 25 patients with inflammatory bowel disease and concurrent melanosis coli found on colonoscopy, only 20% had documented laxative use.[3] The mean duration of inflammatory bowel disease was more than 7 years. These findings raise the possibility of chronic colitis being a potential cause of melanosis coli. Additionally, studies of melanosis coli in pigs have shown an association between high sulfate-containing drinking water and low vitamin E levels with increased oxidative stress.[4][5]

Epidemiology

Wittoesch et al found the incidence of melanosis coli ranged between 0.8% to 1.1% in patients evaluated in Rochester, Minnesota.[6] Approximately 97% of these patients reported chronic constipation, and 96% used chronic laxative therapies; the majority of patients were aged 45 years or older. In a more recent multicenter, retrospective study from China assessing 342,922 colonoscopies performed for screening, surveillance, and diagnostic purposes, the incidence of melanosis coli was 1.8%, with males aged 60 or older at increased risk.[1] Melanosis coli has been reported in younger individuals, particularly in patients with chronic laxative use. Moreover, melanosis coli is equally common in males and females.[1]

Pathophysiology

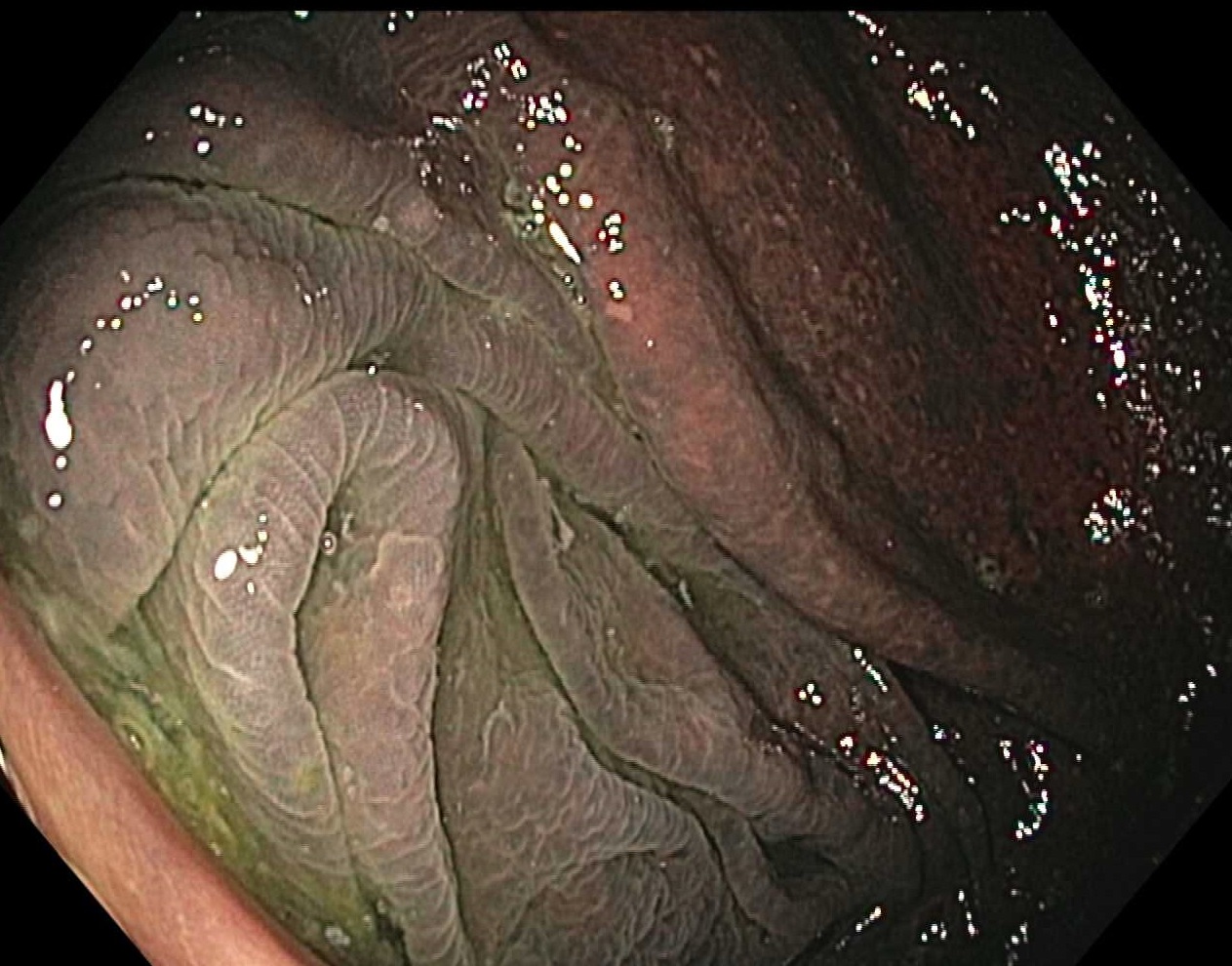

Anthraquinones in laxatives have a direct toxic effect on the epithelial cells of the colon. When these laxative molecules change into their active form in the large intestine, they can cause cell damage to the lining of the large intestine, leading to cell death. As the cells undergo apoptosis, they create a dark pigment called lipofuscin. Examination with electron microscopy demonstrates intraepithelial macrophages ingest these apoptotic bodies and migrate to the lamina propria, where intracellular degradation of apoptotic cells result in lipofuscin formation.[7] The dark pigment of lipofuscin stains the macrophages, leading to a black-brown appearance visible on colonoscopy. Melanosis coli is more common in the proximal bowel and much rarer in the distal colon (see Image. Proximal Colon With Melanosis Coli). This is probably due to the difference in the macrophage distribution in the colonic wall. Once laxative use is halted, the dark pigmentation may resolve.[8]

Li et al used expression microarray analyses to show significant downregulation of cytochrome P450-associated genes (CYP3A4, CYP3A7, UGT2B11, and UGT2B15) in melanosis coli, though further research is needed to elucidate clinical significance and pathogenesis.[9]

Histopathology

Special staining and immunohistochemical analyses of tissue with melanosis coli confirm that the pigmented granules ingested within macrophages are consistent with lipofuscin but not melanin, bile pigment, or hemosiderin.[9] Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain helps to identify the presence of lipofuscin under the microscope. Compared to normal colon tissue, tissue with melanosis coli has increased apoptotic bodies within macrophages and the superficial lamina propria of the colonic epithelium.[7][9]

Toxicokinetics

Anthraquinone-based laxatives work in the following ways:

- They stimulate the active transport of chloride into the gut, which in turn causes an osmotic gradient and pulls water into the gut lumen.

- They inhibit Na-K adenosine triphosphate (ATP)ase on the enterocytes, which further inhibits the reabsorption of water, sodium, and potassium, ultimately excreting it into the feces.

- They stimulate local prostaglandins, which stimulate peristalsis and decrease transit time through the bowel.[10][11]

The adverse effects of senna and other stimulant laxatives include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps. Subsequent hypovolemia can lead to dizziness, palpitations, and syncope.

History and Physical

Typically, melanosis coli causes no symptoms and is incidentally found during a colonoscopy performed for other indications. Findings of melanosis coli should prompt an assessment for a history of constipation, chronic use of anthraquinone-based laxatives, and a history of inflammatory bowel disease or colitis. Clinicians should also review any nonprescription, over-the-counter medications, including herbal supplements and teas, to help capture other sources of stimulant-laxative use.

Evaluation

Melanosis coli is evaluated through colonoscopy and histology, not laboratory studies or other imaging modalities. An endoscopic exam shows a dark-brown discoloration of the colonic mucosa. Characteristically, melanosis coli is most prominent in the proximal colon but can involve other colonic segments.[12][13] Staining of biopsied tissue further demonstrates the presence of lipofuscin particles. If clinical concern for true melanin deposition from diseases, eg, Peutz-Jegher Syndrome, is present, biopsies should be taken for confirmation.

Treatment / Management

Due to the common finding of melanosis coli in anthraquinone-based laxative use, the primary treatment for melanosis coli is the discontinuation of anthraquinone-containing compounds. Resolution of the condition may take several months to a year.[8][13][14][15][16] Alternative constipation therapies that should be considered in patients with melanosis coli that do not cause mucosal hyperpigmentation include osmotic laxatives (eg, polyethylene glycol), bisacodyl, fiber supplements, and secretagogues.(B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Other etiologies for mucosal hyperpigmentation should be considered within the differential of melanosis coli. True melanin deposition in the skin and mucosa can be seen with Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome, an autosomal dominant disorder that leads to numerous hamartomatous polyps in the bowel. Patients with this disease are at a 15-fold increase in developing colon cancer. Panenteric melanosis may also be a presenting finding of metastatic melanoma with scattered macular, black-pigmented spots throughout the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract seen on endoscopy and colonoscopy.[17] Biopsies of these lesions confirm melanin deposition.

Pseudomelanosis with hemosiderin deposition has been reported infrequently in the upper gastrointestinal tract.[18][19][20] This finding is more common in patients with underlying hypertension, chronic renal failure, diabetes mellitus, history of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and oral iron use. Other medications associated with pseudomelanosis include hydralazine, thiazide diuretics, furosemide, and beta-blockers.

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

In cases of anthraquinone overdose, treatment is symptomatic and supportive to correct significant fluid and electrolyte abnormalities. In patients where the diagnosis is unclear or symptoms significant, consultation with a poison center or toxicologist is advised.

Prognosis

The prognosis is good in patients with melanosis coli, as the colonic discoloration will typically resolve after discontinuing the causative laxative. However, this can take months to up to 1 year. Rebound constipation can occur with laxative cessation.[21][22]

Complications

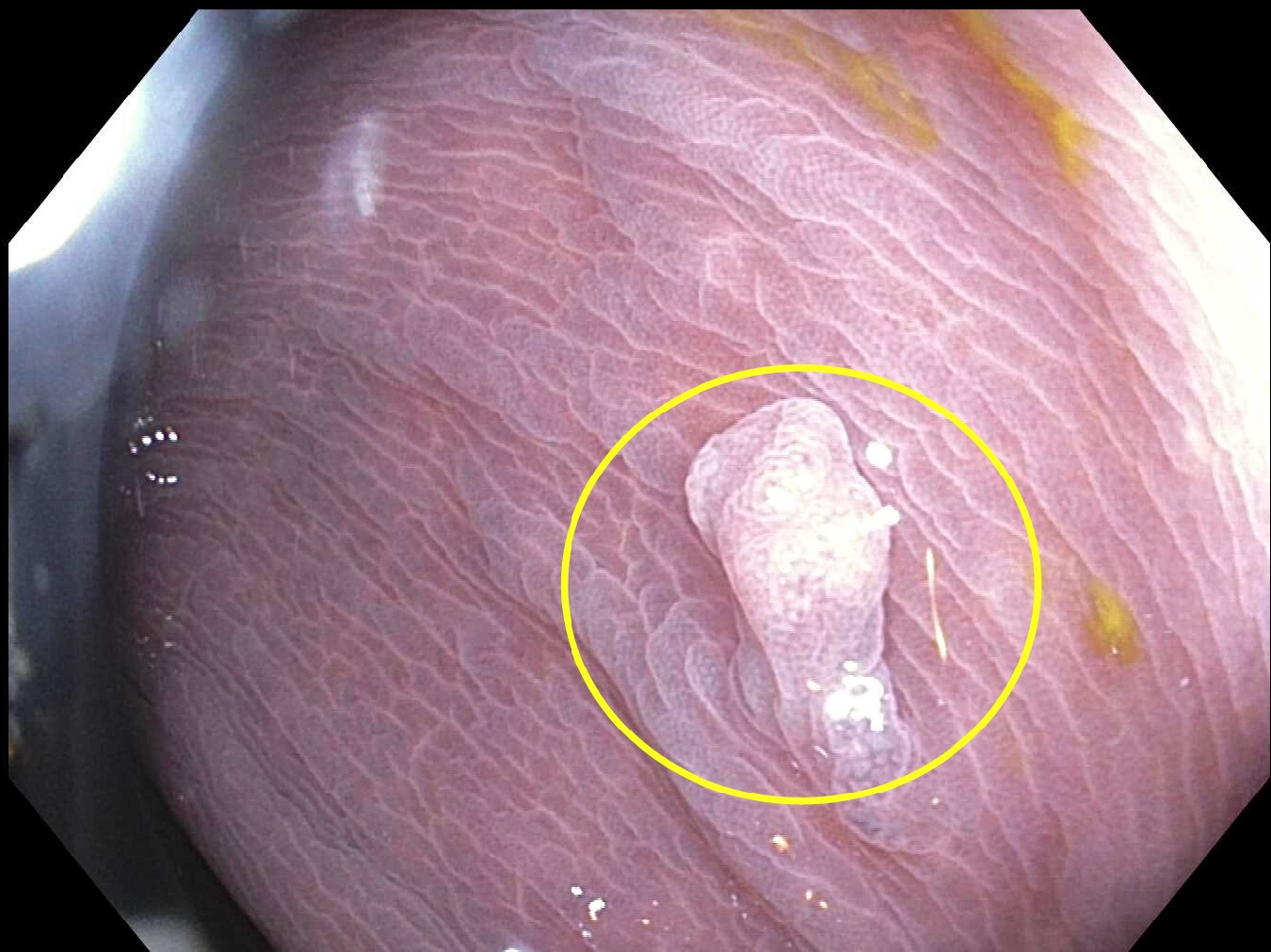

Some research suggests an increased risk of melanosis coli and colon polyps. However, consensus or evidence demonstrating an increased risk of colon cancer has not been documented. The association between melanosis and increased adenomatous polyps is thought to be due to higher mucosal detection during colonoscopy from the color contrast, as hyperpigmentation interestingly spares the adenomatous polyps and thus makes polyp tissue stand out in a darker background (see Image. Colon Polyp).[23]

Increased stimulant laxative use and abuse can cause electrolyte derangements due to the rapid transit through the bowel and decreased absorption of nutrition and water reabsorption. In extreme cases, particularly with potassium imbalance and acute renal injury, the consequences may be fatal.

Consultations

A gastroenterologist can make the diagnosis by performing a colonoscopy to exclude other differential diagnoses. In cases of anthraquinone-based laxative overdose, toxicologists provide helpful guidance.

Deterrence and Patient Education

In patients requiring laxatives for underlying constipation, a healthy diet and lifestyle choices will help patients wean the need for stimulant laxatives (eg, senna). A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes will give the essential fiber to bulk stool and prevent constipation. Adequate hydration of at least 8 glasses of water daily is another key step in having healthy bowel movements.

Clinicians must keep in mind that the intake of other substances can also cause constipation, eg, caffeinated beverages, energy drinks, fried food, excess carbohydrates, alcohol, red meat, and artificial sweeteners. Adequate physical exercise also stimulates the bowels, allowing for peristalsis, which is the rhythmic motion of the intestines, to take place and help with the transit of stool down the digestive tract. Adequate sleep helps the body regulate appropriate bowel health. Reviewing medications to see if there are potential constipating adverse effects and discussing with health practitioners ways to minimize these adverse effects, or considering alternative therapies, are other ways to maintain gut health.

Pearls and Other Issues

Melanosis coli is a benign finding most commonly found incidentally on colonoscopy performed for other indications. This finding is not precancerous or fatal and can improve with the cessation of anthraquinone-containing stimulant laxative use. Further research is ongoing.

Diet alterations and increased physical exercise should be the mainstay and initial treatment for constipation. Oral fiber supplements such as psyllium should be used as the next step. Stimulant laxatives are meant to be a short-term therapy for constipation and should not be used chronically except in patients with chronic motility issues or on constipating medications, eg, opioids and anticholinergics.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of melanosis coli requires a collaborative, interprofessional approach to ensure patient-centered care, improved outcomes, and enhanced patient safety. Physicians and advanced practitioners play a critical role in diagnosing the condition through colonoscopy and histological examination, distinguishing it from more serious colonic pathologies. Nurse practitioners and pharmacists are essential in educating patients about the risks of prolonged laxative use, particularly those containing anthraquinones, to prevent unnecessary healthcare expenditures associated with misdiagnosis. Pharmacists can guide patients toward safer alternatives for constipation relief, such as osmotic laxatives or fiber supplements, while nurses reinforce proper medication adherence and lifestyle modifications.

Care coordination between gastroenterologists, dietitians, and primary care clinicians is crucial in managing patients with melanosis coli. Gastroenterologists should evaluate persistent constipation to identify underlying causes, minimizing the reliance on stimulant laxatives. Dietitians contribute by advising patients on fiber-rich diets and hydration strategies to promote bowel regularity naturally. Regular exercise should be encouraged by all healthcare practitioners, as physical activity plays a significant role in preventing constipation. Through seamless communication among these professionals, patients receive comprehensive, preventive care that reduces the risk of melanosis coli and enhances their overall gastrointestinal health.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Wang S, Wang Z, Peng L, Zhang X, Li J, Yang Y, Hu B, Ning S, Zhang B, Han J, Song Y, Sun G, Nie Z. Gender, age, and concomitant diseases of melanosis coli in China: a multicenter study of 6,090 cases. PeerJ. 2018:6():e4483. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4483. Epub 2018 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 29568709]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYang N, Ruan M, Jin S. Melanosis coli: A comprehensive review. Gastroenterologia y hepatologia. 2020 May:43(5):266-272. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2020.01.002. Epub 2020 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 32094046]

Pardi DS, Tremaine WJ, Rothenberg HJ, Batts KP. Melanosis coli in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 1998 Apr:26(3):167-70 [PubMed PMID: 9600362]

Rodríguez-Gómez IM, Gómez-Laguna J, Ruedas-Torres I, Sánchez-Carvajal JM, Garrido-Medina ÁV, Roger-García G, Carrasco L. Melanosis Coli in Pigs Coincides With High Sulfate Content in Drinking Water. Veterinary pathology. 2021 May:58(3):574-577. doi: 10.1177/0300985821991565. Epub 2021 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 33590812]

Wilberts BL, Schwartz KJ, Gauger PC, Wang C, Burrough ER. Evidence of Oxidative Injury in Pigs With Melanosis Coli. Veterinary pathology. 2015 Jul:52(4):663-7. doi: 10.1177/0300985814559403. Epub 2014 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 25421421]

WITTOESCH JH, JACKMAN RJ, McDONALD JR. Melanosis coli: general review and a study of 887 cases. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 1958 May-Jun:1(3):172-80 [PubMed PMID: 13537819]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWalker NI, Smith MM, Smithers BM. Ultrastructure of human melanosis coli with reference to its pathogenesis. Pathology. 1993 Apr:25(2):120-3 [PubMed PMID: 8367190]

Abu Baker F, Mari A, Feldman D, Suki M, Gal O, Kopelman Y. Melanosis Coli: A Helpful Contrast Effect or a Harmful Pigmentation? Clinical medicine insights. Gastroenterology. 2018:11():1179552218817321. doi: 10.1177/1179552218817321. Epub 2018 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 30574001]

Li XΑ, Zhou Y, Zhou SΧ, Liu HR, Xu JM, Gao L, Yu XJ, Li XH. Histopathology of melanosis coli and determination of its associated genes by comparative analysis of expression microarrays. Molecular medicine reports. 2015 Oct:12(4):5807-15. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4126. Epub 2015 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 26238215]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMalik EM, Müller CE. Anthraquinones As Pharmacological Tools and Drugs. Medicinal research reviews. 2016 Jul:36(4):705-48. doi: 10.1002/med.21391. Epub 2016 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 27111664]

Lombardi N, Bettiol A, Crescioli G, Maggini V, Gallo E, Sivelli F, Sofi F, Gensini GF, Vannacci A, Firenzuoli F. Association between anthraquinone laxatives and colorectal cancer: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic reviews. 2020 Jan 24:9(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-1280-5. Epub 2020 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 31980030]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLecomte T, Chautard R, Orain I. A melanosis coli associated with a large flat adenoma of the cecum. Clinics and research in hepatology and gastroenterology. 2019 Jun:43(3):228-229. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2018.10.006. Epub 2018 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 30447908]

Biernacka-Wawrzonek D, Stępka M, Tomaszewska A, Ehrmann-Jóśko A, Chojnowska N, Zemlak M, Muszyński J. Melanosis coli in patients with colon cancer. Przeglad gastroenterologiczny. 2017:12(1):22-27. doi: 10.5114/pg.2016.64844. Epub 2016 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 28337232]

Cohen GS. Melanosis Coli. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2020 Jun:18(7):e71. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.03.032. Epub 2019 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 30928452]

Moeller J, Solomon R, Kiffin C, Ditchek JJ, Davare DL. Melanosis Coli: A Case of Mistaken Identity-A Case Report. The Permanente journal. 2019:23():18-063. doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-063. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30624202]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChiba T, Wang T, Kikuchi S. Colonoscopic Resolution of Melanosis Coli After Cessation of Senna Laxative Use. International medical case reports journal. 2024:17():783-787. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S475869. Epub 2024 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 39282237]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKaplan MR, Knittel DR, Lawson P, Schafer TW. Panenteric melanosis: an ominous endoscopic finding. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2005 May:61(6):762-5 [PubMed PMID: 15855990]

Tang SJ, Zhang S, Grunes DE. Gastric and duodenal pseudomelanosis: a new insight into its pathogenesis. VideoGIE : an official video journal of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2019 Oct:4(10):467-468. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2019.06.006. Epub 2019 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 31709332]

Rustagi T, Mansoor MS, Gibson JA, Kapadia CR. Pseudomelanosis of stomach, duodenum, and jejunum. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2015 Feb:49(2):124-6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000081. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24492404]

Rinesmith SE, Thomas FB, Marsh WL Jr. Gastric Pseudomelanosis. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2006 Nov:2(11):806-807 [PubMed PMID: 28381950]

Zimmer V, Emrich K. The Rusty Ring Sign Streamlining Flat Lesion Detection in Subtle Melanosis Coli. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2018 Aug:16(8):A33. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.011. Epub 2018 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 29649462]

Klair JS, Chandra S, Johlin FC. Melanosis Coli due to Rhubarb Supplementation. ACG case reports journal. 2019 May:6(5):e00092. doi: 10.14309/crj.0000000000000092. Epub 2019 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 31616757]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBlackett JW, Rosenberg R, Mahadev S, Green PHR, Lebwohl B. Adenoma Detection is Increased in the Setting of Melanosis Coli. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2018 Apr:52(4):313-318. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000756. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27820223]