Introduction

A mallet finger typically refers to an extensor tendon avulsion injury at the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. This can be the result of a direct, isolated rupture of the terminal extensor tendon or due to a distal phalangeal base fracture. In both cases, the result is an inability to actively extend the DIP joint, leading to a characteristic flexion deformity of the fingertip that is often described as resembling a mallet or hammer. This injury most commonly occurs due to sudden, forceful flexion of an extended DIP joint, eg, when a ball strikes the tip of an outstretched finger.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

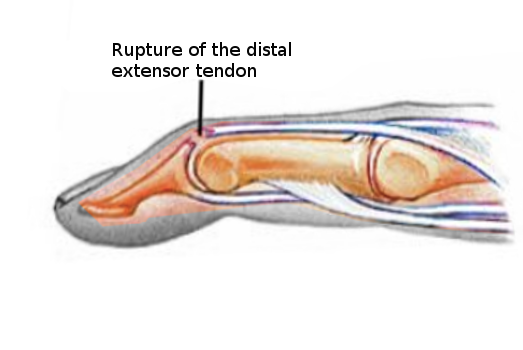

The extrinsic digital extensor tendon originates in the forearm and courses over the metacarpophalangeal joint to form the extensor hood, has a separate direct attachment to the dorsal base of the middle phalanx in the form of the central slip, and finally attaches to the distal phalanx as the terminal tendon. This tendon mechanism is responsible for the extension of the digits.[1] Mallet fingers result from a tear or avulsion of the extensor tendon as it crosses the DIP joint.[2]

Epidemiology

Mallet finger injuries commonly occur in workplace settings or during sports activities, especially ball sports, eg, baseball, basketball, and volleyball. These injuries typically result from a direct blow to the tip of an extended finger, forcing the DIP joint into abrupt flexion, which leads to disruption of the terminal extensor tendon. Epidemiologically, mallet fingers are most commonly seen in young to middle-aged men, likely due to their greater involvement in manual labor and contact or competitive sports, as well as in older females.[3][4] The small, ring, and middle fingers of the dominant hand are most commonly affected.

Pathophysiology

Mallet Finger Injury Pathophysiology

Mallet finger injuries are usually caused by a traumatic event resulting in forced flexion of the extended fingertip, causing the terminal extensor tendon to become attenuated or torn (see Images. Mallet Finger Injury and Mallet Finger Pathophysiology). When the injury reflects an isolated terminal tendon rupture, this is termed a "soft tissue" mallet finger. In more severe injuries, forced digital flexion can cause an avulsion fracture of the dorsal base of the distal phalanx where the terminal tendon inserts, termed a "bony mallet" finger or "mallet fracture."

Mallet finger injuries can also be caused by a laceration or, more rarely, a forced hyperextension of the DIP joint that results in a fracture at the dorsal base of the distal phalanx. Regardless of the mechanism of injury, the disruption of extensor tendon function causes an unopposed flexion force on the finger and is accompanied by the inability to actively extend the digit at the DIP joint, resulting in the classic “mallet” appearance of the finger.

While most mallet finger injuries are closed, open mallet finger injuries can also occur, typically resulting from the following:

- Crush injuries

- Lacerations to the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx

In these uncommon open mallet injuries, the terminal extensor tendon is disrupted, often with exposure of the tendon or bone.[5]

Mallet Finger Injury Classification System (Chronicity)

Mallet finger injuries can be classified as acute or chronic, based on the interval between the injury and the onset of deformity. Acute mallet finger deformities are defined as those occurring within 4 weeks of the injury, while chronic mallet finger deformities are classified as occurring beyond 4 weeks following the injury.

Doyle’s Classification of Mallet Finger Injuries

The following Doyle classification can be used to categorize these injuries and guide treatment:

- Type I: Closed injury, with or without a small dorsal avulsion fracture

- Type II: Open injury due to laceration

- Type III: Open injury from deep abrasion involving skin and tendon loss

- Type IV: Mallet fracture involving the distal phalanx

History and Physical

While the diagnosis of mallet finger injuries is typically made through physical examination, a history of trauma is often described by the patient with a direct blow to the distal phalanx that causes forced flexion of the fingertip. In the acute setting, patients may also report pain and a deformity at the level of the DIP joint.

A thorough physical examination is essential for diagnosing a mallet finger and for assessing any associated injuries. The key evaluative findings and considerations include:

- Inspection of soft tissues: This examination should be the initial step to assess for open wounds, lacerations, or abrasions on the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx, which may indicate an open mallet injury.

- Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints: These joints are assessed for range of motion to identify any concurrent injuries or joint stiffness.

- DIP joint examination: The following findings are classically present in the setting of a mallet finger injury:

- The fingertip rests in approximately 30 to 45 degrees of flexion at the DIP joint.

- The patient is unable to extend the DIP joint actively.

- There may be swelling and/or tenderness to palpation over the dorsal DIP joint, particularly in acute presentations.

- In chronic cases, tenderness may be minimal or absent, but a persistent extensor lag will be evident.

Evaluation

A mallet finger is primarily a clinical diagnosis based upon history and physical examination. However, imaging plays a crucial role in both differentiating between a tendinous ("soft tissue") mallet injury and a "bony" mallet fracture, as well as guiding appropriate management. In general, the following imaging evaluation is recommended:

- Plain radiographs of the affected finger should be obtained to assess bony involvement and joint alignment.

- A 3-view radiographic series (anteroposterior, oblique, and true lateral) is recommended.

Radiographic Findings

The following radiographic findings are commonly noted in patients with mallet finger injuries:

- In tendinous "soft tissue" mallet fingers, radiographs are usually normal as no bony avulsion fracture is present. Flexed posturing of the DIP joint would be noted.

- In "bony" mallet fractures, a bony avulsion fragment is present at the dorsal base of the distal phalanx.

- The true lateral view allows for accurate assessment of the following:

- Size of the fracture fragment

- Degree of displacement

- Presence of volar subluxation of the distal phalanx, which may indicate joint instability and influence treatment considerations

Treatment / Management

Nonoperative Management

The majority of mallet finger injuries can be treated nonoperatively, including acute "soft tissue" mallet fingers and minimally displaced "bony" mallet fractures without DIP joint subluxation. The mainstay of treatment involves an extended period of DIP joint extension splinting to reapproximate the extensor mechanism, facilitating either tendinous or bony healing.

The optimal type of splint and duration of immobilization for mallet finger injuries have evolved over time. Historically, the PIP and DIP joints were immobilized to reduce tension on the extensor mechanism and support tendon healing. However, studies have demonstrated that immobilizing the PIP joint does not influence retraction of the extensor tendon at the DIP joint. As a result, most current guidelines recommend immobilizing only the DIP joint.

The DIP joint should be splinted in full extension (typically between 0 and 10 degrees of hyperextension) continuously (full-time) for 6 to 8 weeks, although some protocols call for extension splinting for up to 12 weeks. During this time, the DIP joint cannot flex at all, as this could disrupt early healing and cause complications. As a consequence, the patient should be advised that any DIP flexion during the splinting process would necessitate restarting the entire 6- to 8-week period (or more). Additionally, to clean the affected digit and preserve skin integrity, the patient should be instructed to carefully remove the splint daily (eg, after bathing) while blocking the finger to prevent flexion. The digit can be cleaned and dried while maintaining full DIP extension, and the splint can then be reapplied.

Interval follow-up appointments to check the skin and confirm continued compliance with the splinting instructions can help promote the best possible outcomes. After the initial splinting period, part-time splinting at night is generally advised for an additional 2 to 6 weeks to support tendon remodeling and prevent recurrence.[8] Several types of splints are used to manage mallet finger injuries, including the Stack or Stax splint, perforated thermoplastic splint, and alumafoam splint.[9][10] Despite the variety, all splints share a common treatment principle: complete immobilization of the DIP joint in full extension or slight hyperextension.(A1)

Operative Management

The treatment of "bony" mallet fractures remains a subject of some debate in the orthopedic and hand surgery literature.[11][12][13] The management is primarily determined by the degree of articular surface involvement and the presence or absence of volar subluxation of the distal phalanx.[14] In general, closed mallet fractures involving less than one-third of the articular surface, without associated distal interphalangeal subluxation, can be managed nonsurgically with splinting, as previously noted.[15](A1)

Operative treatment is generally recommended when volar subluxation of the DIP joint is present, as this suggests joint instability and a greater risk of poor functional outcomes if left untreated.[16] Some surgeons advocate for surgical fixation when the fracture fragment involves more than one-third of the articular surface or >2 mm of articular gapping is noted, even in the absence of joint subluxation. This recommendation is driven by concerns about possible complications, including delayed subluxation, extensor lag, and posttraumatic osteoarthritis.

In such cases, the primary aim of surgery is to restore joint congruity and potentially improve the long-term function of the DIP joint. The selection of a surgical technique is primarily determined by the fracture fragment size, location, complexity, surgeon expertise, and clinical discretion.[17][18][19] Ultimately, the choice between surgical and nonsurgical management should be tailored to the individual patient, considering factors including:

- Age

- Hand dominance

- Occupation and activity level

- Functional requirements

- Willingness and ability to comply with splinting protocols

The surgical approach may involve any of the following techniques:

- Closed reduction and percutaneous pinning (CRPP): A single trans-articular Kirschner (K)-wire fixing the DIP joint in extension or a (modified) Ishiguro technique with dual K-wires (one pinning the DIP joint in extension and another dorsal extension block wire)

- Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF): A dorsal midline incision centered over the DIP joint is made to visualize the fracture fragment directly. Reduction is achieved manually, and the fragment is secured with a K-wire, cerclage wire, or a combination thereof.

- Direct repair of the ruptured terminal tendon: This is reserved for open injuries, as direct repair of closed "soft tissue" mallet injuries generally has poor postoperative outcomes.

- DIP joint arthrodesis: Fusion of the joint is achieved with K-wires or an intramedullary screw when the mallet finger is associated with notable DIP osteoarthritis.

Regardless of the treatment pursued, most mallet finger injuries require referral to a hand therapist after adequate healing has occurred to restore range of motion and strength.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses that should also be considered when evaluating mallet finger injuries include:

- Osteoarthritis

- Phalangeal fractures (acute or malunion)

- Seymour fracture

- Swan neck deformity

- Metacarpophalangeal injuries

- Open wounds to the proximal digital extensor tendon

Treatment Planning

The goal of treatment for mallet finger injuries is to have a functional, congruent DIP joint over the long term.

Prognosis

Most patients with mallet finger injuries have acceptable outcomes with conservative treatment. Surgical interventions are often associated with a higher risk of complications, whereas nonoperative treatment typically results in minimal functional impairment of the DIP joint and digit.

Complications

Extensor lag represents the most frequently observed complication following mallet finger injuries. This condition reflects an inability to fully and actively extend the DIP joint. A mild extensor lag ranging from 5 to 20 degrees, typically around 10 degrees, may persist even after appropriate treatment. In most cases, this residual lag does not produce meaningful functional impairment.[6]

Joint stiffness, especially at the DIP joint, may develop due to prolonged immobilization during the treatment process. Limited motion can affect recovery and overall hand function if not addressed during rehabilitation.

Swan neck deformity, characterized by hyperextension of the PIP joint and flexion of the DIP joint, may occur as a result of contracture within the extensor mechanism. This imbalance leads to secondary hyperextension of the PIP joint, altering finger mechanics and appearance.[20]

Malunion or nonunion may result when a "bony" mallet fracture heals improperly or fails to heal. These outcomes can contribute to persistent deformity or functional deficits in the affected digit.

Posttraumatic osteoarthritis often develops when the articular surface sustains significant injury. Long-term consequences may include chronic pain, stiffness, and structural deformity of the joint, which can potentially impair hand function and quality of life.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

For mallet finger injuries being treated nonoperatively, the DIP joint should be kept in extension with uninterrupted (full-time) splinting for 6 to 8 weeks (or more). If full extension is maintained without any extensor lag at the end of this period, nighttime splinting is then advised. Patients involved in heavy manual work or sports should continue to protect their fingers by using a splint or buddy taping during activity for a further 6 to 8 weeks to reduce the risk of reinjury.

If treated operatively, the affected digit will undergo a period of protected immobilization, the duration of which depends on the specific fixation or repair technique used and the surgeon's preference. Once adequate healing has been documented, patients are referred to a hand therapist to improve their range of motion and overall pinch and grip strength.

Consultations

Surgical referral to an orthopedic or plastic hand surgeon may be warranted in the following situations:

- Subluxation of the DIP joint

- A fracture involving more than 30% to 40% of the articular surface

- Inability to achieve full passive extension of the DIP joint

- Complete rupture or laceration of the extensor tendon

- Complex injuries

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education play a crucial role in the successful management and prevention of complications related to mallet finger injuries. Patients should receive clear instructions on the mechanism of injury, emphasizing how sudden, forceful flexion of an extended fingertip, eg, during sports or daily activities, can cause extensor tendon disruption.

Education must emphasize the importance of early recognition and prompt treatment to prevent long-term deformity or dysfunction. During conservative management, patients should understand the critical need for uninterrupted DIP joint extension throughout the splinting period, as even brief flexion can reset the healing timeline. Consequently, patients should be advised that any flexion of the DIP joint during the healing phase can undo the progress made and may necessitate restarting the treatment with another 6 to 8 (or more) weeks of continuous splinting. This may also result in a suboptimal final aesthetic and functional result. Daily cleaning of the finger while maintaining full extension and proper splint reapplication must be demonstrated to preserve skin integrity and promote compliance.

Additionally, clinicians should explain potential complications, eg, extensor lag, swan neck deformity, stiffness, and arthritis, especially if instructions are not followed precisely. Educating patients about the importance of follow-up appointments and hand therapy after immobilization helps optimize outcomes, restore function, and reduce the risk of recurrence or long-term disability.

Pearls and Other Issues

A mallet finger typically occurs when the DIP joint is abruptly flexed, often due to a sudden impact to the tip of an extended finger. Typically, a high-velocity load to the end of the digit results in stretch or rupture of the terminal extensor tendon. Thorough testing of the extension at the DIP joint is crucial for diagnosing a mallet injury. Notably, an extensor lag may not be immediately noticeable during the initial evaluation.

Open mallet injuries are managed with primary tendon repair (tenorrhaphy) combined with fixation of the DIP joint. Closed mallet injuries are typically treated with continuous, full-time immobilization of the DIP joint in full extension using a splint for 6 to 8 (or more) weeks.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Optimal management of mallet finger injuries relies on coordinated efforts among physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, hand therapists, and other healthcare professionals to support timely diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and patient-centered care. Emergency physicians and primary care clinicians often serve as the initial point of contact, requiring the skills to recognize the injury, differentiate between soft tissue and bony involvement, and initiate proper imaging. Advanced practitioners and nurses contribute by reinforcing patient education, ensuring splint compliance, monitoring skin integrity, and coordinating follow-up care to support patient recovery. Their responsibilities include teaching patients how to properly clean and reapply splints without disrupting the DIP joint extension, a critical factor in successful nonoperative management.

When cases involve complex fractures or volar subluxation of the distal phalanx, referral to a hand surgeon becomes essential. Interprofessional communication between the referring clinician and the surgical team ensures continuity of care and a clear understanding of indications for operative intervention. Hand therapists play a vital role during rehabilitation, guiding patients through exercises to restore strength and range of motion while preventing extensor lag or joint stiffness. Pharmacists may support the team by managing analgesia and advising on medications that minimize inflammation or support postoperative recovery. Regular team discussions, shared decision-making, and seamless care coordination improve patient outcomes, ensure safety, and enhance team performance in both conservative and surgical pathways for mallet finger injuries.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Colzani G, Tos P, Battiston B, Merolla G, Porcellini G, Artiaco S. Traumatic Extensor Tendon Injuries to the Hand: Clinical Anatomy, Biomechanics, and Surgical Procedure Review. Journal of hand and microsurgery. 2016 Apr:8(1):2-12. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1572534. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27616821]

Ramponi DR, Hellier SD. Mallet Finger. Advanced emergency nursing journal. 2019 Jul/Sep:41(3):198-203. doi: 10.1097/TME.0000000000000251. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31356243]

STARK HH, BOYES JH, WILSON JN. Mallet finger. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1962 Sep:44-A():1061-8 [PubMed PMID: 14039487]

Chung DW, Lee JH. Anatomic reduction of mallet fractures using extension block and additional intrafocal pinning techniques. Clinics in orthopedic surgery. 2012 Mar:4(1):72-6. doi: 10.4055/cios.2012.4.1.72. Epub 2012 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 22379558]

Cheung JP, Fung B, Ip WY. Review on mallet finger treatment. Hand surgery : an international journal devoted to hand and upper limb surgery and related research : journal of the Asia-Pacific Federation of Societies for Surgery of the Hand. 2012:17(3):439-47. doi: 10.1142/S0218810412300033. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23061962]

Lin JS, Samora JB. Surgical and Nonsurgical Management of Mallet Finger: A Systematic Review. The Journal of hand surgery. 2018 Feb:43(2):146-163.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.10.004. Epub 2017 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 29174096]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKhera B, Chang C, Bhat W. An overview of mallet finger injuries. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis. 2021 Nov 3:92(5):e2021246. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92i5.11731. Epub 2021 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 34738569]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLamaris GA, Matthew MK. The Diagnosis and Management of Mallet Finger Injuries. Hand (New York, N.Y.). 2017 May:12(3):223-228. doi: 10.1177/1558944716642763. Epub 2016 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 28453357]

Zhu X, Chen X, Lv Y, Chen Y, Gao W, Yan H. The Importance of Active Exercise in Treatment of Tendinous Mallet Finger: Insights From a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. The Journal of hand surgery. 2025 Feb 5:():. pii: S0363-5023(24)00635-X. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2024.12.011. Epub 2025 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 39918530]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShafiee E, Farzad M, Beikpour H. Orthotic Intervention with Custom-made Thermoplastic Material in Acute and Chronic Mallet Finger Injury: A Comparison of Outcomes. The archives of bone and joint surgery. 2024:12(3):176-182. doi: 10.22038/ABJS.2023.60506.2985. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38577511]

Geyman JP, Fink K, Sullivan SD. Conservative versus surgical treatment of mallet finger: a pooled quantitative literature evaluation. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 1998 Sep-Oct:11(5):382-90 [PubMed PMID: 9796768]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWehbé MA, Schneider LH. Mallet fractures. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1984 Jun:66(5):658-69 [PubMed PMID: 6725314]

Handoll HH, Vaghela MV. Interventions for treating mallet finger injuries. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2004:(3):CD004574 [PubMed PMID: 15266538]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMoradi A, Kachooei AR, Mudgal CS. Mallet fracture. The Journal of hand surgery. 2014 Oct:39(10):2067-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.06.022. Epub 2014 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 25135247]

Smit JM, Beets MR, Zeebregts CJ, Rood A, Welters CFM. Treatment options for mallet finger: a review. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2010 Nov:126(5):1624-1629. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ef8ec8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21042117]

Kuşcu B, Gürbüz K. Extension-block pinning versus custom-made plate fixation technique: A comparison of two methods in the treatment of osseous mallet finger injuries. Ulusal travma ve acil cerrahi dergisi = Turkish journal of trauma & emergency surgery : TJTES. 2025 Jan:31(1):84-94. doi: 10.14744/tjtes.2024.15332. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39775506]

Uzun M, Bulbul M, Ozturk K, Ayanoğlu S, Adanir O, Gürbüz H. Surgical treatment of mallet fractures by extension block Kirschner wire technique surgical treatment of mallet fractures. Acta ortopedica brasileira. 2012:20(5):297-9. doi: 10.1590/S1413-78522012000500010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24453621]

Zhang H, Du S, Zhu J. A novel surgical technique for direct fixation of bony mallet finger with K-wires. The Journal of hand surgery, European volume. 2025 Jul:50(7):979-981. doi: 10.1177/17531934241299214. Epub 2024 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 39579372]

Adıgüzel IF, Ertem H. Protective suture technique in chronic tendinous mallet finger deformities. Annales de chirurgie plastique et esthetique. 2025 Jul:70(4):335-340. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2025.04.002. Epub 2025 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 40374448]

Rockwell WB, Butler PN, Byrne BA. Extensor tendon: anatomy, injury, and reconstruction. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2000 Dec:106(7):1592-603; quiz 1604, 1673 [PubMed PMID: 11129192]