Introduction

Low back pain ranks among the most common musculoskeletal complaints encountered in clinical practice. As the leading cause of disability in the developed world, it contributes to billions of dollars in healthcare expenditures each year. Despite variations across epidemiological studies, the incidence of low back pain ranges from 5% to 10%, with a lifetime prevalence of 60% to 90%. Most episodes resolve without the need for extensive intervention, responding well to brief rest, activity modification, and physical therapy. Approximately 50% of cases improve within 1 to 2 weeks, and up to 90% show resolution within 6 to 12 weeks.[1]

Lumbosacral facet syndrome describes a clinical condition characterized by unilateral or bilateral back pain that may radiate to the buttocks, groin, or thighs, typically stopping above the knee.[2] In certain cases, symptoms of facetogenic pain resemble those of radiculopathy caused by herniated discs or nerve root compression. Repetitive overuse and routine daily activities contribute to degeneration of the facet joints, potentially resulting in microinstability and the formation of synovial facet cysts that compress adjacent nerve roots.[3]

Facet joints contribute to approximately 15% to 45% of low back pain cases, with degenerative osteoarthritis serving as the most prevalent source of facet-related discomfort.[4] A thorough history and physical examination may aid in diagnosing facet joint syndrome. Although radiographs, computed tomography (CT) scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are frequently employed, imaging findings often fail to correlate reliably with clinical symptoms. Diagnostic blocks can help identify facet joints as the pain generator, while treatment options, eg, intraarticular steroid injections or neurolysis through radiofrequency or cryoablation, offer relief from facetogenic pain.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Degenerative Processes

Lumbosacral facet syndrome can occur secondary to repetitive overuse and microtrauma, spinal strains and torsional forces, poor body mechanics, obesity, and intervertebral disk degeneration over the years. This notion is supported by the strong association between the incidence of facet arthropathy and increasing age.[5] The most common etiology of facet joint pain is degenerative osteoarthritis of the facet joints, which is closely associated with the degeneration of the intervertebral discs.[4] As in all synovial joints, osteoarthritis involves narrowing of the joint space, loss of synovial fluid and cartilage, and bony overgrowth. The inflammation generated by degeneration of facet joints and surrounding tissues is believed to cause localized pain. Risk factors for lumbar facet joint osteoarthritis include age, sex, facet orientation (sagitally oriented), spinal level (L4 to L5), and associated background of intervertebral disc degeneration.

Intervertebral disc degeneration is often related to the amount of heavy work done before the age of 20. However, the association between degenerative changes in the lumbar facet joints and symptomatic low back pain remains unclear and is subject to continued debate.[6] Synovial facet joint cysts may occur in the setting of facet arthritis and may cause radiculopathy or symptomatic spinal stenosis from nerve root impingement.[7] This may lead to presentation with radicular symptoms rather than what is more often localized low back pain, typical of facet joint syndrome.

Spondylolisthesis

Degenerative spondylolisthesis occurs due to the displacement of 1 vertebra relative to another in the sagittal plane. This is typically related to most cases of facet joint osteoarthritis and failure of segmental movement, which occurs due to subluxation of the facet joints, resulting in progressive loss of cartilage and articular remodeling, leading to instability and increased capsular tension.[8] Spondylolisthesis most commonly occurs at the L4 to L5 level, often in association with osteoarthritis.[9] In younger patients aged 30 to 40, spondylolisthesis can occur due to congenital abnormalities, isthmic spondylolisthesis, or acute or stress-related fractures. Compared to degenerative disease, L5 to S1 is the most affected and is more frequently associated with instability.

Septic Facet Arthritis

Septic arthritis is a rare etiology of facet joint syndrome.[10] An isolated form should raise suspicion for an iatrogenic cause, eg, tuberculosis or, in one reported case, Kingella kingae.

Inflammatory Conditions

Ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis are seronegative spondyloarthropathies that may also involve the lumbar facet joints, as the facet joints are synovial in nature.[4]

Epidemiology

Low back pain is the second most significant cause of absenteeism in the workplace, behind upper respiratory tract infections. Approximately 25 million people miss 1 or more work days due to low back pain, and more than 5 million are disabled from it. Patients with chronic back pain account for 80% to 90% of all healthcare expenditures.[11] The high health care costs can be attributed to multiple factors, including imaging overuse, a lack of accurate diagnosis, work stoppages, and unwarranted surgery. Low back pain can lead to functional limitations and cause difficulty performing typical daily tasks, especially in older adults.

The cited prevalence of lumbosacral facet arthropathy is highly variable in the literature, ranging from 5% to greater than 90%. Many of the studies investigating the prevalence of facetogenic pain used a combination of history, physical examination, and radiologic imaging, which is relatively unreliable in establishing a diagnosis. This likely accounts for the wide range seen in estimated prevalence. A trend consistently observed in studies is that the prevalence of lumbosacral facet syndrome tends to increase with age. A 2004 study by Manchikanti et al found that of 397 patients screened, 198 (50%) obtained an initial positive response to medial branch block with lidocaine. Of those patients, 124 patients (31%) reported "definite pain relief" when they received treatment with a repeat medial branch block using bupivacaine.

Pathophysiology

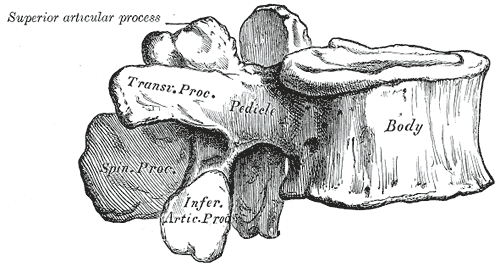

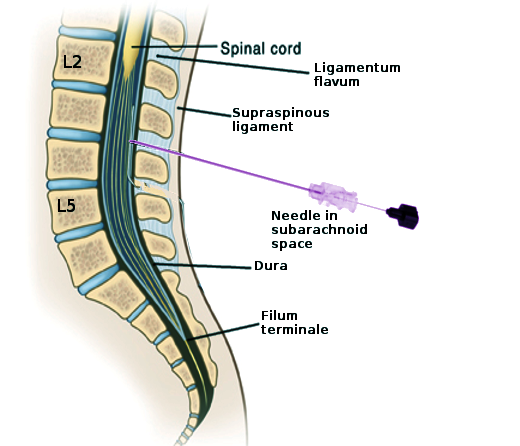

The spine consists of 7 cervical, 12 thoracic vertebrae, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 4 coccyx bones. Each spinal segment consists of an intervertebral disc with posterior paired synovial (facet) joints comprising a "3-joint complex," where each component influences the others, and degenerative changes in 1 joint lead to biochemical changes in the whole complex (see Image. Lumbar Vertebra, Lateral View). Facet joints constitute the posterolateral articulation, which connects the posterior arch between vertebral levels. They are diarthrodial and paired joints and are the only synovial joints of the spine, with hyaline cartilage overlying subchondral bone, a synovial membrane, and a joint capsule. The joint space has a capacity of 1 to 2 mL (see Image. Lumbar Puncture Landmarks).[12]

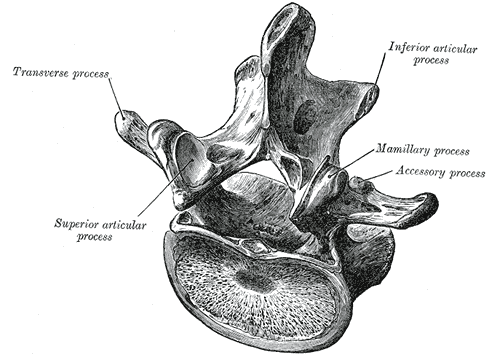

The lumbar facets are composed of the inferior articular process of the vertebra above and the superior articular process of the vertebra below (see Image. Lumbar Vertebra, Superoposterior View). The zygapophyseal joints stabilize the spine and prevent injury by limiting the spinal range of motion. The facet joints are true synovial joints. The articular surface is contained in a cartilaginous sheath over an encapsulated fibrous capsule. Like other cartilaginous joints, the lumbar facets are prone to degradation over time and can cause chronic low back pain when irritated.[13] The sensory innervation of the facet is supplied by the medial branch of the posterior rami of the spinal nerve at the same level and 1 level above the facet joint. For example, the L3 to L4 medial branch receives innervation from the L2 and L3 medial branch nerves. Noxious stimulation of the medial branches is caused by degenerative changes in the facet joint, which results in facet pain and lumbosacral facet syndrome.[14]

History and Physical

Low back pain and other degenerative spinal conditions can present with varying degrees of pain, disability, radiculopathy, and neurologic deficits. The clinical picture can be ambiguous for even skilled clinical practitioners.

Clinical Presentations

In most presentations, facetogenic lumbosacral pain often presents secondary to chronic pain alone. It should, however, be noted that facet joint pain may be referred distally into the lower limb, thus mimicking sciatica. In these cases of "pseudo-radicular" lumbar pain, patients typically experience radiation into the unilateral or bilateral buttocks and the trochanteric region (from L4 and L5 levels), the groin and thighs (from L2 to L5), ending above the knee, and without any neurologic deficits.

At times, pain may radiate further down the lower extremity, reaching the foot, thus mimicking sciatic pain. This may occur primarily in the setting of large synovial cysts, causing direct mechanical compression and creating ensuing inflammation that further irritates the surrounding nerve roots.[15] Facet joint pain is typically worse in the mornings and following periods of inactivity. Stress exercise, lumbar spinal extension or rotary motions, standing or sitting positions, and facet joint palpation may also elicit lumbar facetogenic pain.[2]

Physical Examination

In any case of low back pain, a physical examination is key in determining etiology. The examination should begin with inspecting the back to rule out any visible abnormalities. Palpation should be performed to evaluate for areas of palpable tenderness or paraspinal hypertonicity. Range of motion with active lumbosacral flexion and extension should be performed with the patient standing.

While standing, lumbosacral facet loading should be performed, especially when low back pain is suspected to have a facetogenic etiology. This maneuver is performed by having the patient extend and rotate the spine. This increases pressure on the facet joints, thus eliciting a pain response. However, studies have shown that facet loading is unreliable in diagnosing facetogenic pain. Additionally, paraspinal muscle tenderness is weakly associated with facetogenic pain, although this finding is nonspecific.[16] After facet loading, the patient may sit on the table to allow for the remainder of the standard neuromuscular low back examination.

Lower extremity muscle strength should be assessed with hip flexion, knee extension, ankle dorsiflexion, big toe extension, and ankle plantarflexion to evaluate the L2 to S1 myotomes. Light touch sensory examination should be performed throughout the L2 to S1 lower extremity dermatomes. Patellar (L4) and Achilles (S1) reflexes should be elicited. Straight-leg raise testing is then performed with the patient in a supine position. The examiner gently raises the patient's leg by flexing the hip with the knee in extension, with dorsiflexion as an added maneuver for test sensitivity. The test is considered positive if pain is elicited by hip flexion at an angle lower than 45 degrees, with pain typically reported as shooting down the leg.[17]

A positive straight leg raise test may be helpful in the workup of lumbar facetogenic pain, as a positive test may indicate radiculopathy with disc herniation rather than facet dysfunction. While in the supine position, hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation can be performed. This positioning stresses the sacroiliac joint and, if positive, can point away from facetogenic etiology of back pain. Hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation may also be performed, which indicates intraarticular hip pathology rather than lumbar facet joint pain.

Evaluation

Radiographic Assessment

The physical examination can help rule out other causes of chronic low back pain; however, studies have shown that the physical exam is relatively nonspecific. Degenerative changes in the facet joints can be visualized in radiologic studies. The initial radiographic assessment of a patient presenting with lumbar facet-mediated pain typically includes anterior-posterior, lateral, and oblique views (see Image. Grade II Spondylolisthesis).[18] Oblique radiographs are considered the best view for evaluating lumbar facet joints because of their oblique position, generating a "Scottie dog" view.

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

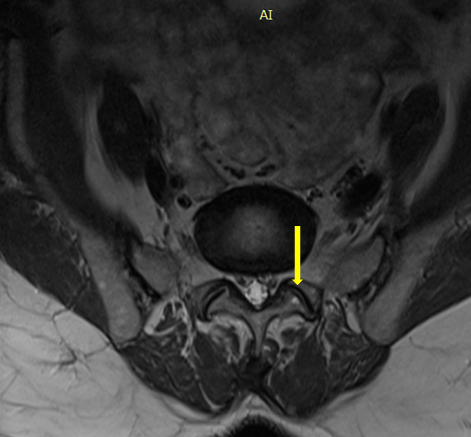

CT scan improves the anatomic assessment of the facet joints and is thus the preferred method for imaging facet joint osteoarthritis (see Image. Facet Joint).[19] Facet joint degeneration is characterized by joint space narrowing, sclerosis, subchondral erosions, cartilaginous thinning, joint capsule calcification, hypertrophy of articular processes, and the ligamentum flavum leading to impingement of the foramina and osteophytes. In patients with chronic low back pain, degenerative changes on CT scans are cited to range from 40% to 85%.[20]

While CT and MRI are equally applicable in demonstrating morphological changes in facet joint degeneration, MRI presents the advantages of better assessing the consequences of facet joint degeneration, such as surrounding neural structural impingement.[21] Studies have shown MRI to be more than 90% sensitive and specific in visualizing facet degeneration.[22] It should, however, be noted that currently, no consensus has been established on how best to evaluate lumbar facet joint osteoarthritis with imaging. It has, however, been reported that in clinical practice, imaging findings of degeneration (including radiographs, CT, and MRI) have been associated with nonspecific low back pain.[23]

Imaging and Clinical Presentation Correlation

Radiographic changes due to osteoarthritis can be seen equally among symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, and thus, radiological investigations report a poor correlation between clinical symptoms and spinal degeneration.[24] The upside of imaging in evaluating facet joint dysfunction often lies in its ability to rule out "red flag" differential diagnoses (neoplasm, cauda equina syndrome, aortic aneurysm or dissection, or fracture) rather than to prove a symptomatic facet joint arthritis.[25]

Due to the poor correlation between history, physical exam, and lumbosacral facet syndrome, diagnostic blocks are the mainstay in establishing a diagnosis. Of note, false positive results have been documented to be as high as 25% to 40% in the lumbar spine.[26] Because of this, experts recommend performing 2 diagnostic medial branch blocks to confirm a diagnosis. A positive response is considered to be greater than 80% pain relief after the procedure.[27]

Treatment / Management

Treatment for lumbosacral facet syndrome usually includes an interprofessional approach. If the diagnosis is uncertain, consideration is given to performing diagnostic medial branch blocks.

Nonoperative Treatment

Nonoperative management includes oral medications such as NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and oral steroids during acute flares. Additionally, weight loss and physical therapy have demonstrated successful outcomes.[28]

Minimally Invasive Treatment

Because no concrete clinical features or diagnostic imaging studies can definitively determine whether a facet joint is painful, medial branch nerve blocks serve as the only accurate means of diagnosing the facet joint as the etiology of a patient's low back pain. At least 80% pain reduction and the ability to perform previously painful movements following medial branch block is considered a definitive diagnosis for facet-induced low back pain.[29] It should, however, be noted that more liberal criteria have reported greater than 50% pain relief as diagnostic.[30] A definitive diagnosis of facet joint-mediated pain may require blocks at 2 different sessions. Performing only a single-level block results in a high false-positive rate (30 to 45%). For this reason, many have therefore advocated for the performance of repeated blocks.[27] (B2)

A study by Cohen et al demonstrated a success rate of 39% for patients undergoing lumbar facet joint radiofrequency ablation after a single block and 64% after 2 blocks.[31] Due to the dual nerve supply of the facet joints at the same level and the level above, diagnostic nerve blocks should be performed at a minimum of 2 levels to block a single joint.[29] Diagnostic blocks typically include local anesthesia (eg, lidocaine or bupivacaine), either with or without steroids. (A1)

Following a successful medial branch block, patients may proceed with neurolysis of the medial branches. Radiofrequency probes should be placed at 2 subsequent levels because of the dual nerve supply of a given facet joint. Radiofrequency and cryoneurolysis are the most commonly used techniques for this purpose. In both of these techniques, electrical stimulation monitoring should be performed before injecting local anesthetics and creating thermal lesions to ensure safety during thermal denervation. While ablation may be helpful in facetogenic pain treatment, it should be noted that it does not allow for definite pain relief, as the destroyed nerve will eventually regenerate, causing possible pain recurrence.[30] (B3)

In such cases, the procedure may be repeated. A prospective study by Dreyfuss et al demonstrated that 60% of patients could expect at least a 90% reduction in pain, while 87% could expect at least a 60% reduction, which lasted for 12 months.[32] Potential adverse effects of radiofrequency ablation include painful cutaneous dysesthesias or hyperesthesia, neuroma formation, and increased pain due to neuritis. Unintentional spinal nerve damage, causing a motor deficit, is another rare complication.[33] Multifidus atrophy has also been seen following radiofrequency ablation, with more profuse atrophy following repeated ablation.

Intraarticular facet joint corticosteroid injections represent another minimally invasive treatment avenue. With the injection of inflammatory mediators into and around a degenerative facet joint, short to intermediate-term pain relief is often seen. It should, however, be noted that discrepancies persist in the literature regarding the efficacy of steroids for facet joint pain.[34] (A1)

Additional treatments for lumbosacral facet syndrome have emerged in recent years. Orthobiologic therapies are continuing to be studied for multiple musculoskeletal and spine conditions, including lumbosacral facet syndrome. Recent studies have shown therapeutic promise in using intraarticular orthobiologic therapies, including mesenchymal stem cells, platelet-rich plasma, and alpha-2-macroglobulin, in managing facet-mediated axial spinal pain.[35] Specifically, the phase 1 Cellkine clinical trial suggested safety and feasibility with administering intra-articular allogenic mesenchymal stem cells, offering therapeutic benefits for pain management and functional improvement.[36] Peripheral nerve stimulation of the lumbar medial branches has emerged as a promising therapy for facetogenic pain.[37][38] Fluoroscopy-guided high-frequency ultrasound neurotomy is an emerging therapy that demonstrates promise as a minimally invasive therapy with clinical responses comparable to traditional RFA without requiring any needles.[39][40][41](A1)

For the above minimally invasive techniques, imaging guidance has been shown to enhance both the technical and clinical efficacy of the procedure, while also reducing potential complications. Fluoroscopy has classically been the preferred method of imaging guidance, as studies have found ultrasound guidance for medial branch and facet procedures to be associated with a significant risk for incorrect needle placement.[42] Common complications of all facet joint procedures include bleeding, infection, and vasovagal syncope.[43](A1)

Surgical Treatment

Indications for surgical intervention include:

- Symptoms refractory to nonoperative modalities (eg, 3 to 6 month trial)

- Large associated synovial facet cyst correlating with clinical exam and presentation

- Laminectomy with decompression is the classic first-line treatment for symptomatic, intraspinal synovial cysts

- The literature also supports the utilization of facetectomy, decompression, and instrumented fusion (as opposed to a simple "laminectomy decompression")

Differential Diagnosis

While at times difficult, an attempt should be made to differentiate lumbosacral facet joint syndrome from other conditions with similar clinical features through a thorough history and physical examination. While a history of pain radiation to the lower extremity can point more towards radiculopathy or discogenic pain, clinicians should remember that such presentation may also indicate facetogenic pain, especially in facet joint cysts.

Physical examination, although not always completely definitive, may help rule out certain diagnoses in the differential. Pain with hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation and hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation may point more towards sacroiliac and intraarticular hip pathology, respectively. A positive straight leg raise test may point more towards lumbosacral radiculopathy or discogenic pain. However, these tests are often nonspecific. While imaging with x-ray, CT, and MRI may be useful in evaluating spinal anatomy, these tests are also often nonspecific in diagnosing the true etiology of pain. Lumbar medial branch block, therefore, serves as the most reliable definitive diagnosis of the facet joint as the true etiology of a patient's low back pain. Differential diagnoses of lumbosacral facet joint syndrome include:

- Lumbosacral discogenic pain syndrome

- Lumbar disc herniation

- Lumbosacral facet syndrome

- Lumbosacral radiculopathy

- Lumbosacral spine acute bony injuries

- Lumbosacral spine sprain and strain injuries

- Lumbosacral spondylolisthesis

- Lumbosacral spondylosis

- Paraspinal muscle or ligament, sprain or strain

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Seronegative spondyloarthritis (most commonly ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and reactive arthritis)

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- Infection

- Neoplasm

- Fibromyalgia

- Intraarticular hip pathology

- Piriformis syndrome

- Sacroiliac joint injury

Treatment Planning

When history and physical examination indicate lumbosacral facet syndrome, treatment should be initiated with physical therapy and medication if needed. Physical therapy includes lumbosacral stretching and strengthening, as well as exercises that target core strengthening. Therapeutic modalities, including heat, ice, deep tissue massage, myofascial release, and ultrasound treatment, may also be beneficial in managing symptomatic low back pain associated with facet joint dysfunction. Medication treatment regimens for lumbosacral facet joint syndrome may start with acetaminophen or the physician's choice of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication.

If the patient's pain persists despite these measures, or if the patient is unable to tolerate therapy due to the severity of their pain, the patient should be evaluated for minimally invasive interventions, either with medial branch block followed by radiofrequency ablation if successful or with intraarticular facet joint injection. Surgical treatment should be referred for severe pain refractory to the above management and may include laminectomy, facetectomy, decompression, or instrumented fusion.

Prognosis

Lumbosacral facet joint syndrome will increase with age, especially when secondary to its most common cause, facet joint osteoarthritis. Conservative treatments, including physical therapy, should serve as first-line management. Patients who fail conservative treatment with physical therapy and medications may undergo a diagnostic medial branch block indicative of facetogenic etiology of pain. In patients with successful diagnostic blocks, radiofrequency ablation has been shown to relieve pain for 6 months up to 1 year, at which time repeat neurolysis may be performed if indicated.

Complications

Serious complications of interventions used in treating lumbosacral facet joint syndrome are rare. Any intraarticular steroid injection carries a risk of metabolic and endocrine adverse effects related to elevations in glucose levels and suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Case reports have detailed infection following intraarticular steroid injection, including epidural abscess, septic arthritis, and meningitis.

Other complications of spinal injections include dural puncture and spinal anesthesia. The most common reported radiofrequency ablation complication is neuritis, with a reported incidence of 5%.[44] It should be noted that transient numbness or dysesthesias have been reported, as well as other rare complications, including burns resulting from electrical faults.

Deterrence and Patient Education

As part of physical therapy, patients should be educated on home exercises and proper posture as an initial treatment. Given the correlation between obesity and the development of lumbosacral facet joint dysfunction, weight loss counseling serves as an essential tool in preventing the development of facetogenic pain. Patients should seek a professional evaluation from an orthopedist, a physiatrist, or a spinal surgeon to receive a thorough assessment and rule out more serious "red flag" etiologies of low back pain before implementing a proper treatment plan.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Enhancing patient-centered care for individuals with lumbosacral facet joint syndrome requires coordinated efforts across an interprofessional healthcare team. Effective care begins with a strong clinician-patient relationship, fostering trust and shared decision-making. Physicians and advanced practitioners must collaborate to accurately diagnose and distinguish facet-mediated pain from other sources of low back pain through thorough history-taking, physical examination, and appropriate imaging or diagnostic blocks. Once identified, modifiable risk factors such as poor posture, obesity, and physical inactivity should be addressed through personalized plans that involve physical therapists and dietitians. Nurses play a crucial role in educating patients, monitoring progress, and facilitating communication between clinicians and patients to reinforce adherence and clarify expectations.

Interprofessional communication is crucial for integrating nonoperative, interventional, and pharmacological strategies safely and effectively. Pharmacists contribute by reviewing medications for interactions and counseling patients on the appropriate use of NSAIDs, steroids, or adjunctive therapies. Pain specialists and physiatrists coordinate the timing and selection of interventions such as radiofrequency neurotomy or intraarticular injections, ensuring alignment with the patient’s goals and overall care plan. Recurrence of pain is common, so team-based follow-up is critical for reassessment, adapting treatment strategies, and preventing chronicity. Through aligned responsibilities and collaborative care, the healthcare team can improve patient safety, outcomes, and satisfaction while maximizing the efficiency and performance of the care team.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Lumbar Vertebra, Superoposterior View. This illustration shows the relationship between a typical lumbar vertebra's transverse process, superior and inferior articular processes, and mamillary and accessory processes. Shown but not labeled are the laminae, spinal canal, lateral recess, pedicles, and vertebral body.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Lumbar Puncture Landmarks. This image shows the key structures encountered during a lumbar puncture for diagnostic, anesthetic, or therapeutic purposes. Labeled structures include L2, L5, the spinal cord, ligamentum flavum, supraspinous ligament, dura, and filum terminale. The needle is in the subarachnoid space at the L3-L4 level.

Contributed by S Bhimji, MD

References

Bogduk N. Degenerative joint disease of the spine. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2012 Jul:50(4):613-28. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.04.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22643388]

Manchikanti L, Singh V, Pampati V, Damron KS, Barnhill RC, Beyer C, Cash KA. Evaluation of the relative contributions of various structures in chronic low back pain. Pain physician. 2001 Oct:4(4):308-16 [PubMed PMID: 16902676]

Grgić V. [Lumbosacral facet syndrome: functional and organic disorders of lumbosacral facet joints]. Lijecnicki vjesnik. 2011 Sep-Oct:133(9-10):330-6 [PubMed PMID: 22165083]

Perolat R, Kastler A, Nicot B, Pellat JM, Tahon F, Attye A, Heck O, Boubagra K, Grand S, Krainik A. Facet joint syndrome: from diagnosis to interventional management. Insights into imaging. 2018 Oct:9(5):773-789. doi: 10.1007/s13244-018-0638-x. Epub 2018 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 30090998]

Marcia S, Masala S, Marini S, Piras E, Marras M, Mallarini G, Mathieu A, Cauli A. Osteoarthritis of the zygapophysial joints: efficacy of percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy in the treatment of lumbar facet joint syndrome. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2012 Mar-Apr:30(2):314 [PubMed PMID: 22409995]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKalichman L, Li L, Kim DH, Guermazi A, Berkin V, O'Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U, Cole R, Hunter DJ. Facet joint osteoarthritis and low back pain in the community-based population. Spine. 2008 Nov 1:33(23):2560-5. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318184ef95. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18923337]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChazen JL, Leeman K, Singh JR, Schweitzer A. Percutaneous CT-guided facet joint synovial cyst rupture: Success with refractory cases and technical considerations. Clinical imaging. 2018 May-Jun:49():7-11. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2017.10.013. Epub 2017 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 29120814]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCavanaugh JM, Ozaktay AC, Yamashita HT, King AI. Lumbar facet pain: biomechanics, neuroanatomy and neurophysiology. Journal of biomechanics. 1996 Sep:29(9):1117-29 [PubMed PMID: 8872268]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAkkawi I, Zmerly H. Degenerative Spondylolisthesis: A Narrative Review. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis. 2022 Jan 19:92(6):e2021313. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92i6.10526. Epub 2022 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 35075090]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRajeev A, Choudhry N, Shaikh M, Newby M. Lumbar facet joint septic arthritis presenting atypically as acute abdomen - A case report and review of the literature. International journal of surgery case reports. 2016:25():243-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.07.001. Epub 2016 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 27414995]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceManchikanti L, Boswell MV, Singh V, Pampati V, Damron KS, Beyer CD. Prevalence of facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2004 May 28:5():15 [PubMed PMID: 15169547]

Datta S, Lee M, Falco FJ, Bryce DA, Hayek SM. Systematic assessment of diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic utility of lumbar facet joint interventions. Pain physician. 2009 Mar-Apr:12(2):437-60 [PubMed PMID: 19305489]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKozera K, Ciszek B, Szaro P. Posterior Branches of Lumbar Spinal Nerves - part II: Lumbar Facet Syndrome - Pathomechanism, Symptomatology and Diagnostic Work-up. Ortopedia, traumatologia, rehabilitacja. 2017 Apr 12:19(2):101-109 [PubMed PMID: 28508761]

Bogduk N. Functional anatomy of the spine. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2016:136():675-88. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53486-6.00032-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27430435]

Ening G, Kowoll A, Stricker I, Schmieder K, Brenke C. Lumbar juxta-facet joint cysts in association with facet joint orientation, -tropism and -arthritis: A case-control study. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2015 Dec:139():278-81. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.10.030. Epub 2015 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 26546887]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFalco FJ, Manchikanti L, Datta S, Sehgal N, Geffert S, Onyewu O, Singh V, Bryce DA, Benyamin RM, Simopoulos TT, Vallejo R, Gupta S, Ward SP, Hirsch JA. An update of the systematic assessment of the diagnostic accuracy of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks. Pain physician. 2012 Nov-Dec:15(6):E869-907 [PubMed PMID: 23159979]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCamino Willhuber GO, Piuzzi NS. Straight Leg Raise Test. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969539]

Varlotta GP, Lefkowitz TR, Schweitzer M, Errico TJ, Spivak J, Bendo JA, Rybak L. The lumbar facet joint: a review of current knowledge: part 1: anatomy, biomechanics, and grading. Skeletal radiology. 2011 Jan:40(1):13-23. doi: 10.1007/s00256-010-0983-4. Epub 2010 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 20625896]

Schwarzer AC, Wang SC, O'Driscoll D, Harrington T, Bogduk N, Laurent R. The ability of computed tomography to identify a painful zygapophysial joint in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995 Apr 15:20(8):907-12 [PubMed PMID: 7644955]

Boswell MV, Manchikanti L, Kaye AD, Bakshi S, Gharibo CG, Gupta S, Jha SS, Nampiaparampil DE, Simopoulos TT, Hirsch JA. A Best-Evidence Systematic Appraisal of the Diagnostic Accuracy and Utility of Facet (Zygapophysial) Joint Injections in Chronic Spinal Pain. Pain physician. 2015 Jul-Aug:18(4):E497-533 [PubMed PMID: 26218947]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceClarençon F, Law-Ye B, Bienvenot P, Cormier É, Chiras J. The Degenerative Spine. Magnetic resonance imaging clinics of North America. 2016 Aug:24(3):495-513. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2016.04.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27417397]

Smuck M, Crisostomo RA, Trivedi K, Agrawal D. Success of initial and repeated medial branch neurotomy for zygapophysial joint pain: a systematic review. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2012 Sep:4(9):686-92. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.06.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22980421]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHofmann UK, Keller RL, Walter C, Mittag F. Predictability of the effects of facet joint infiltration in the degenerate lumbar spine when assessing MRI scans. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2017 Nov 21:12(1):180. doi: 10.1186/s13018-017-0685-x. Epub 2017 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 29162138]

Kalichman L, Li L, Hunter DJ, Been E. Association between computed tomography-evaluated lumbar lordosis and features of spinal degeneration, evaluated in supine position. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2011 Apr:11(4):308-15. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.02.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21474082]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLateef H, Patel D. What is the role of imaging in acute low back pain? Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2009 Jun:2(2):69-73. doi: 10.1007/s12178-008-9037-0. Epub 2009 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 19468875]

Bogduk N. On diagnostic blocks for lumbar zygapophysial joint pain. F1000 medicine reports. 2010 Aug 9:2():57. doi: 10.3410/M2-57. Epub 2010 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 21173871]

Manchukonda R, Manchikanti KN, Cash KA, Pampati V, Manchikanti L. Facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain: an evaluation of prevalence and false-positive rate of diagnostic blocks. Journal of spinal disorders & techniques. 2007 Oct:20(7):539-45 [PubMed PMID: 17912133]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNelson AM, Nagpal G. Interventional Approaches to Low Back Pain. Clinical spine surgery. 2018 Jun:31(5):188-196. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000542. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28486278]

Manchikanti L, Kosanovic R, Pampati V, Sanapati MR, Soin A, Knezevic NN, Wargo BW, Hirsch JA. Equivalent Outcomes of Lumbar Therapeutic Facet Joint Nerve Blocks and Radiofrequency Neurotomy: Comparative Evaluation of Clinical Outcomes and Cost Utility. Pain physician. 2022 Mar:25(2):179-192 [PubMed PMID: 35322977]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBogduk N, Dreyfuss P, Govind J. A narrative review of lumbar medial branch neurotomy for the treatment of back pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2009 Sep:10(6):1035-45. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00692.x. Epub 2009 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 19694977]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCohen SP, Williams KA, Kurihara C, Nguyen C, Shields C, Kim P, Griffith SR, Larkin TM, Crooks M, Williams N, Morlando B, Strassels SA. Multicenter, randomized, comparative cost-effectiveness study comparing 0, 1, and 2 diagnostic medial branch (facet joint nerve) block treatment paradigms before lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. Anesthesiology. 2010 Aug:113(2):395-405. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e33ae5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20613471]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDreyfuss P, Halbrook B, Pauza K, Joshi A, McLarty J, Bogduk N. Efficacy and validity of radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain. Spine. 2000 May 15:25(10):1270-7 [PubMed PMID: 10806505]

Pacetti M, Fiaschi P, Gennaro S. Percutaneous radiofrequency thermocoagulation of dorsal ramus branches as a treatment of "lumbar facet syndrome"--How I do it. Acta neurochirurgica. 2016 May:158(5):995-8. doi: 10.1007/s00701-016-2759-7. Epub 2016 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 26979181]

Appeadu M, Miranda-Cantellops N, Mays B, Carino Mason Renee, Reynolds J, Samarakoon T, Price C, Monteith Sereen. The Effectiveness of Intraarticular Cervical Facet Steroid Injections in the Treatment of Cervicogenic Headache: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pain physician. 2022 Sep:25(6):459-470 [PubMed PMID: 36122255]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceManchikanti L, Abd-Elsayed A, Kaye AD, Sanapati MR, Pampati V, Shekoohi S, Hirsch JA. A Systematic Review of Regenerative Medicine Therapies for Axial Spine Pain of Facet Joint Origin. Current pain and headache reports. 2025 Mar 14:29(1):61. doi: 10.1007/s11916-025-01376-1. Epub 2025 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 40085275]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYan D, Zubair AC, Osborne MD, Pagan-Rosado R, Stone JA, Lehman VT, Durand NC, Kubrova E, Wang Z, Witter DM, Baer MM, Ponce GC, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Qu W. CellKine clinical trial: first report from a phase 1 trial of allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in subjects with painful lumbar facet joint arthropathy. Pain reports. 2024 Oct:9(5):e1181. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000001181. Epub 2024 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 39300992]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceD'Souza RS, Jin MY, Abd-Elsayed A. Peripheral Nerve Stimulation for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. Current pain and headache reports. 2023 May:27(5):117-128. doi: 10.1007/s11916-023-01109-2. Epub 2023 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 37060395]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGilmore CA, Deer TR, Desai MJ, Hopkins TJ, Li S, DePalma MJ, Cohen SP, McGee MJ, Boggs JW. Durable patient-reported outcomes following 60-day percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) of the medial branch nerves. Interventional pain medicine. 2023 Mar:2(1):100243. doi: 10.1016/j.inpm.2023.100243. Epub 2023 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 39239603]

Perez J, Gofeld M, Leblang S, Hananel A, Aginsky R, Chen J, Aubry JF, Shir Y. Fluoroscopy-Guided High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Neurotomy of the Lumbar Zygapophyseal Joints: A Clinical Pilot Study. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2022 Jan 3:23(1):67-75. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnab275. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34534337]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGofeld M, Smith KJ, Bhatia A, Djuric V, Leblang S, Rebhun N, Aginsky R, Miller E, Skoglind B, Hananel A. Fluoroscopy-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound neurotomy of the lumbar zygapophyseal joints: a prospective, open-label study. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2024 Apr 5:():. pii: rapm-2024-105345. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2024-105345. Epub 2024 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 38580339]

Gofeld M, Tiennot T, Miller E, Rebhun N, Mobley S, Leblang S, Aginsky R, Hananel A, Aubry JF. Fluoroscopy-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation of the lumbar medial branch nerves: dose escalation study and comparison with radiofrequency ablation in a porcine model. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2025 May 6:50(5):429-436. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2024-105417. Epub 2025 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 38508592]

Ashmore ZM, Bies MM, Meiling JB, Moman RN, Hassett LC, Hunt CL, Cohen SP, Hooten WM. Ultrasound-guided lumbar medial branch blocks and intra-articular facet joint injections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain reports. 2022 May-Jun:7(3):e1008. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000001008. Epub 2022 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 35620250]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVelickovic M, Ballhause TM. Delayed onset of a spinal epidural hematoma after facet joint injection. SAGE open medical case reports. 2016:4():2050313X16675258 [PubMed PMID: 27803810]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCohen SP, Raja SN. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2007 Mar:106(3):591-614 [PubMed PMID: 17325518]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence