Introduction

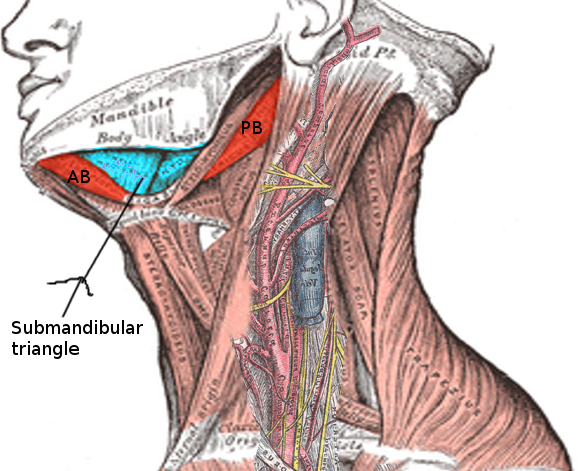

Ludwig angina is a rare, life-threatening condition characterized by diffuse cellulitis that involves the soft tissues of the floor of the mouth and neck. The condition is named after the German physician, Wilhelm Friedrich von Ludwig, who described it in 1836. "Angina" is derived from the Latin angere, meaning "to choke."[1][2] Ludwig angina involves 3 compartments of the floor of the mouth: the sublingual, submental, and submandibular spaces (see Image. Submandibular Triangle). True Ludwig angina originates from an infection of a lower molar tooth.

However, the term is frequently applied to any infection of the floor of the mouth involving the sublingual or submandibular spaces. Involvement of these deep structures and spaces, particularly those located beneath the mylohyoid muscle, presents the greatest risk for airway compromise and other life-threatening clinical complications.[3][4] Infection can spread rapidly and progress to adjacent issues, potentially leading to severe outcomes such as airway obstruction, aspiration pneumonia, and carotid arterial rupture or sheath abscess. Early recognition and treatment are critical, including emergent airway management, intravenous antibiotic therapy, and surgical drainage if an abscess is present.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Ludwig angina most commonly originates from dental infections involving the mandibular molars, particularly the second and third molars, which account for 90% of cases.[5] Periapical abscesses of these teeth are the most common specific source of infection.[6] Less common etiologies include oral piercings or lacerations, mandibular fractures, traumatic intubation, osteomyelitis, peritonsillar or parapharyngeal abscess, submandibular sialadenitis, and infected thyroglossal duct cysts.[7][8]

Predisposing dental factors for Ludwig angina include poor oral hygiene, dental caries, and recent dental treatment.[6] Although the condition often develops in otherwise healthy individuals, several systemic risk factors have been identified. These include diabetes mellitus, alcohol use disorder, malnutrition, and immunosuppression, such as in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or those who have undergone an organ transplant.[3][9]

Epidemiology

Ludwig angina does not demonstrate a significant sex predilection. Airway compromise remains the leading cause of mortality.[10] Before the advent of antibiotics, the mortality rate exceeded 50%.[8] Advances in airway management, antibiotic therapy, imaging, and surgical intervention have decreased mortality to approximately 8% in the modern era.[11]

Pathophysiology

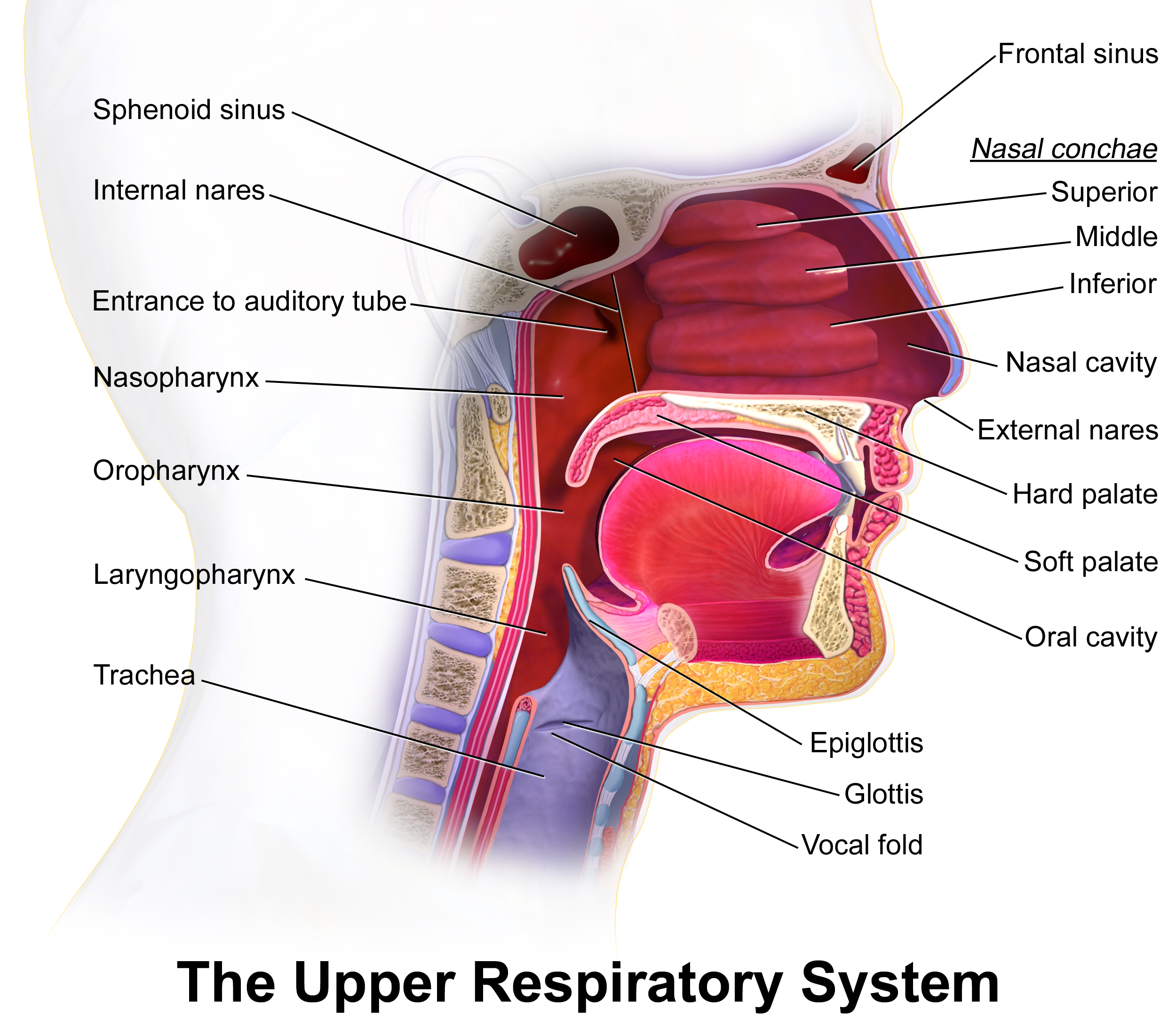

Ludwig angina typically begins in the floor of the mouth and rapidly extends to the submandibular space.[12] The floor of the mouth is divided by the mylohyoid muscle into the sublingual space (above the muscle) and the submandibular space (below the muscle). The roots of the mandibular molars are located inferior to the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle, facilitating the direct spread of odontogenic infections into the submandibular space.[6] Involvement of both the sublingual and submandibular spaces can lead to tongue elevation and airway obstruction if not promptly addressed.[6] Additionally, the infection may cause edema of critical airway structures, such as epiglottitis, vocal cords, and aryepiglottic folds, which can occur within 30 minutes after symptom onset.[6]

The infection may further extend to the parapharyngeal space, retropharyngeal space, and superior mediastinum via the styloglossus muscle (see Image. The Upper Respiratory System).[12] Spread occurs through direct extension along fascial planes rather than via the lymphatic system.[12] Clinically, the progression of infection into the neck is often characterized by a "bull neck" appearance, resulting from the swelling and induration.[12]

Microbiology

Ludwig angina is usually polymicrobial, involving both aerobic and anaerobic oral flora. The most commonly isolated organisms include Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, and Actinomyces.[13] Infection with Streptococcus anginosus is associated with a more rapid disease progression than other bacteria.[14] In patients with diabetes, Klebsiella pneumoniae is isolated in cultures from over half of Ludwig angina cases.[12] Additionally, individuals with diabetes, those on hemodialysis, or with recent hospitalization (within 1 year) have an increased risk of infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.[6]

History and Physical

Patients often report recent dental pain, particularly involving the lower molars. Common systemic symptoms include fever, fatigue, chills, and generalized weakness. As the infection progresses, trismus (limited jaw opening) may develop, indicating involvement of the parapharyngeal space and more severe disease. Signs of respiratory distress, such as tripod positioning (leaning forward with hands on knees to optimize breathing), drooling (due to inability to manage oral secretions), and dysphagia, may also appear. These symptoms collectively signal impending airway obstruction, necessitating urgent intervention.[5][15]

Other signs and symptoms include mouth pain, changes in voice, drooling, tongue swelling, elevation of the floor of the mouth, and a stiff neck.[11] These features reflect the extent of soft tissue involvement and can help differentiate Ludwig angina from other deep neck infections. The physical appearance of Ludwig angina is often described as a "bull neck," characterized by pronounced submental fullness and loss of mandibular angle definition (see Image. Submandibular Swelling).[16] On examination, patients typically present with fever, submental and submandibular swelling, and tenderness. Intraoral findings include swelling of the floor of the mouth, trismus, tongue elevation, and tenderness of the affected teeth. Common extraoral findings include induration of the submental neck and edema in the upper neck. Notably, palpable lymphadenopathy is typically absent.[8]

Evaluation

Ludwig angina is primarily diagnosed through clinical evaluation, as imaging does not play a direct role in the initial assessment. The most critical clinical decision is airway management, given the potential for rapid deterioration. Once the airway is secured, contrast-enhanced neck computed tomography (CT) is the imaging modality of choice for assessing the extent of infection and evaluating for the presence of abscess formation.[17] CT findings suggest Ludwig angina include soft tissue stranding, muscle edema, subcutaneous fat attenuation, loss of fat planes in the submylohyoid space, and soft tissue thickening.[6] Ultrasound, including point-of-care ultrasound, may also be helpful in early detection and airway evaluation.[6]

Although commonly performed in clinical practice, laboratory testing has limited immediate value in diagnosing Ludwig angina, which is primarily a clinical diagnosis. Blood cultures should be obtained to assess for possible hematogenous spread. While cultures from the affected area, obtained via swab or needle aspiration, have limited diagnostic value in the early stages of Ludwig angina, they may be helpful if an abscess is subsequently drained and can be sent for microbiological analysis.[6]

Treatment / Management

The primary objective in treating Ludwig angina is to secure the airway, as asphyxiation from airway obstruction is the leading cause of mortality. Once the airway is stabilized, management focuses on infection control through the use of intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and surgical drainage, if an abscess is present, often necessitating the extraction of the involved teeth. Intravenous corticosteroids and nebulized adrenaline can be adjuvant treatments to reduce facial and airway edema.[6][18]

Airway Management

Patients who are hypoxic should receive supplemental oxygen.[6] Neck swelling and trismus can complicate mask ventilation, making pre-oxygenation essential before any airway intervention.[6] Tongue elevation and trismus complicate the placement of an oropharyngeal airway. Additionally, patients often poorly tolerate airway distress, reducing their ability to cooperate with airway manipulation. Awake, flexible fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation is the preferred method of securing the airway; however, preparations for a surgical airway, such as cricothyrotomy, must be in place before attempting any procedure.[19][20] Flexible nasotracheal intubation requires an experienced clinician. If intubation is not possible, emergency cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy may be necessary, especially in the advanced stages of the infection.[21] Early airway management is critical, as stridor and cyanosis are late and ominous signs of impending airway failure.(B2)

Blind nasotracheal intubation, which involves placing an endotracheal tube without direct visualization of the larynx, should be avoided in patients with Ludwig angina. This procedure can provoke bleeding, rupture abscesses, exacerbate edema, and trigger laryngospasm.[6][21] Supraglottic airway devices may be difficult or impossible to insert due to trismus and can be rendered ineffective or displaced as swelling progresses.[6](B3)

Intravenous Antibiotics

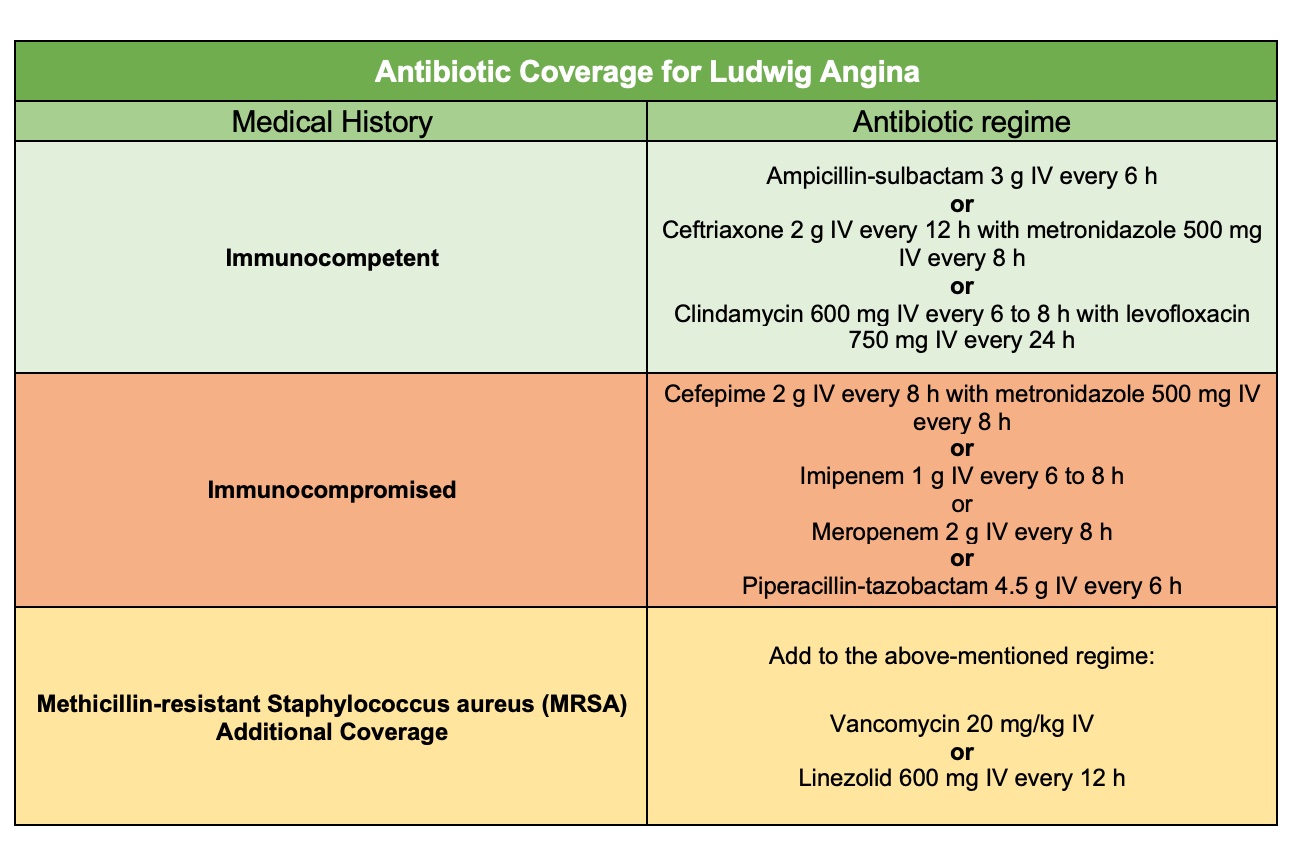

Once the airway is secured, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are the first-line treatment.[8] Antibiotic therapy should provide coverage against both aerobic and anaerobic microflora, as well as oral microflora.[6] Commonly prescribed agents include ampicillin-sulbactam or clindamycin. For individuals who are immunocompromised, broader coverage is necessary to include gram-negative rods and beta-lactamase-producing aerobes and anaerobes. Suitable options in these cases include cefepime, meropenem, or piperacillin-tazobactam.[22] Additionally, clinicians should consider methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) coverage in immunocompromised individuals, those with increased risk factors for MRSA, or individuals with a prior history of MRSA infection. MRSA coverage includes the addition of vancomycin or linezolid to the existing antibiotic regimen (see Image. Antibiotic Coverage for Ludwig Angina).[6][8](B3)

Intravenous Corticosteroids

Intravenous steroids and nebulized adrenaline (epinephrine) can be used as adjuvant treatment to reduce edema and cellulitis, facilitate intubation, and enhance antibiotic penetration into the fascial spaces.[18] Several case reports have noted a reduced need for airway intervention with the use of steroids.[7] Dexamethasone (10 mg intravenous) is the most commonly administered corticosteroid in these cases.[6] However, due to limited evidence, steroid use has not yet become a standard of care and remains at the discretion of the treating physician. Similarly, while data are limited, nebulized epinephrine may also help reduce airway obstruction.[6](B3)

Surgical Drainage

Although the evidence remains controversial, early surgical decompression of the submandibular space may improve airway patency in patients with Ludwig angina.[6][23] Surgical intervention aims to relieve pressure and reopen the oropharyngeal airway by allowing the tongue to shift into a more anteroinferior position.[24] Incisions are typically made parallel and approximately 2 fingerbreadths inferior to the mandibular angle; in some cases, multiple incisions are required.[25] (B2)

Subsequent steps include displacing the submandibular gland and dividing the mylohyoid muscles to decompress the affected fascial compartments.[9] Although surgical decompression of the floor of the mouth may reduce the need for prolonged intubation and shorten the hospital stay, performing this procedure without a discrete abscess is not considered the standard of care.[24] Surgical decompression is indicated in Ludwig angina when imaging reveals a visible abscess, fluctuance is present on physical examination, or there is no clinical improvement with antibiotic therapy alone.[26][27] Prompt surgical intervention under these circumstances can prevent further airway compromise and reduce the risk of systemic complications.(B2)

Differential Diagnosis

While Ludwig angina is primarily diagnosed through clinical evaluation, distinguishing it from other conditions can be challenging in the early stages. In such cases, imaging can be helpful to rule out alternative diagnoses. However, imaging should only be performed after securing the airway or in stable individuals who can breathe comfortably and manage their secretions while in a supine position.

Prognosis

Before the advent of antibiotics, the mortality rate of Ludwig angina exceeded 50%, primarily due to life-threatening airway obstruction.[8] Advances in antibiotic therapy, imaging modalities, and surgical techniques have significantly reduced the mortality rate to approximately 8%.[11]

Complications

Ludwig angina is a rapidly progressive cellulitis that can lead to airway obstruction, often requiring immediate intervention. The presence of airway symptoms or an inability to manage oral secretions is a clear indication for elective intubation to prevent life-threatening complications. Furthermore, close monitoring is essential to prevent the spread of cellulitis to adjacent areas, which can lead to complications such as mediastinitis or neck cellulitis. Additionally, Ludwig angina can progress to aspiration pneumonia. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis, which predominantly occurs through the retropharyngeal space (71%) or the carotid sheath (21%), is a severe complication that requires immediate recognition and management.[7] Sepsis resulting in multiple organ failure is common, particularly in those who are immunocompromised.[2]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Odontogenic infection is the leading cause of Ludwig angina. Providing safety education to patients with dental infections is vital in mitigating the risk of severe complications.[2] Red flag symptoms that may indicate worsening swelling and the need for emergency management include:

- Significant mouth-opening restriction

- Bilateral submandibular swelling

- "Hot potato" voice

- Fever

- Firm or swollen floor of the mouth

- Restricted tongue mobility

- Swallowing difficulty

- Drooling [2]

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about Ludwig angina include the following:

- Ludwig angina is a rapidly progressing cellulitis of the floor of the mouth that involves the submandibular, sublingual, and submental spaces.

- This condition is often caused by dental infections, particularly those affecting the second and third lower molars.

- Infection spreads beneath the mylohyoid muscle, causing swelling of the tongue and airway obstruction.

- Mixed aerobic and anaerobic bacteria are commonly involved (Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Bacteroides, Fusobacterium).

- Individuals with diabetes may have a Klebsiella pneumoniae infection; immunocompromised or recently hospitalized patients are at increased risk of MRSA.

- Risk factors include diabetes, immunosuppression, poor dental hygiene, recent dental work, alcohol use, and age older than 65.

- Signs and symptoms include dental pain, fever, trismus, drooling, tongue swelling and elevation, neck swelling (“bull neck”), difficulty swallowing, and respiratory distress (characterized by a tripod position).

- Serious complications include airway obstruction (leading cause of death), mediastinitis, aspiration pneumonia, and sepsis.

- Diagnosis is primarily clinical, but a CT scan with contrast may be obtained after the airway is secured to assess for abscesses and spread.

- Treatment priority is airway management (awake fiberoptic intubation is preferred; a surgical airway is used if needed).

- Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics covering aerobes and anaerobes (ampicillin-sulbactam or clindamycin; add vancomycin if MRSA suspected).

- Surgical drainage is needed if there is an abscess or no antibiotic improvement.

- Mortality was over 50% before antibiotics; now it is about 8% with prompt treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Ludwig angina is a rapidly progressive cellulitis that can quickly cause airway obstruction. Risk factors for increased mortality and complications are age older than 65, immunosuppression, diabetes, and alcohol consumption.[6] The condition requires immediate intervention and close monitoring to prevent death from asphyxiation. The infection may also result in mediastinitis, necrotizing cellulitis of the neck, and aspiration pneumonia.

Due to the rarity of Ludwig angina, many emergency clinicians have limited experience managing this condition.[7] Securing and maintaining the airway is the primary priority for all affected patients.[7] Early involvement of the otolaryngology, anesthesiology, or oral maxillofacial surgery teams is essential to optimize outcomes and ensure patient safety.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Upper Respiratory System. Illustration of the critical structures and spaces of the upper respiratory system.

Blausen.com staff. Medical Gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine. doi: 10.15347/wjm/2014.010.

ISSN 2002-4436. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)] via Wikimedia Commons.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Antibiotic Coverage for Ludwig Angina. Table of antibiotics and recommended dosages for bacterial coverage in Ludwig angina.

Modified from Bridwell, R., Gottlieb, M., Koyfman, A., & Long, B. (2021). Diagnosis and management of Ludwig's angina: An evidence-based review. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 41, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.12.030

References

Yale SH, Tekiner H, Yale ES. Terminological Insights in Ludwig Angina: Evaluating Pseudo Tongue, Double Tongue, and Ludwig Sign. The American journal of medicine. 2024 Apr:137(4):e79. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.12.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38604724]

Miah MR, Ali AS. Ludwig's angina. British dental journal. 2020 Sep:229(5):268. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-2132-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32917993]

Spitalnic SJ, Sucov A. Ludwig's angina: case report and review. The Journal of emergency medicine. 1995 Jul-Aug:13(4):499-503 [PubMed PMID: 7594369]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChaabouni H, Bechraoui R, Kriaa M, Zainine R, Besbes G. Ludwig's Angina. La Tunisie medicale. 2023 Aug-Sep:101(8-9):718-720 [PubMed PMID: 38445409]

Quinn FB Jr. Ludwig angina. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 1999 May:125(5):599 [PubMed PMID: 10326824]

Bridwell R, Gottlieb M, Koyfman A, Long B. Diagnosis and management of Ludwig's angina: An evidence-based review. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2021 Mar:41():1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.12.030. Epub 2020 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 33383265]

Saifeldeen K, Evans R. Ludwig's angina. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2004 Mar:21(2):242-3 [PubMed PMID: 14988363]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBansal A, Miskoff J, Lis RJ. Otolaryngologic critical care. Critical care clinics. 2003 Jan:19(1):55-72 [PubMed PMID: 12688577]

Barakate MS, Jensen MJ, Hemli JM, Graham AR. Ludwig's angina: report of a case and review of management issues. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2001 May:110(5 Pt 1):453-6 [PubMed PMID: 11372930]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGodse A, Abhishek A, Shamanna K, Puttamadaiah GM, Ramabhadraiah AK. Insights into Retropharyngeal Space Lesions: Our Clinical Experience. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2025 Jan:77(1):271-278. doi: 10.1007/s12070-024-05168-8. Epub 2024 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 40066405]

Moreland LW, Corey J, McKenzie R. Ludwig's angina. Report of a case and review of the literature. Archives of internal medicine. 1988 Feb:148(2):461-6 [PubMed PMID: 3277567]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDowdy RAE, Emam HA, Cornelius BW. Ludwig's Angina: Anesthetic Management. Anesthesia progress. 2019 Summer:66(2):103-110. doi: 10.2344/anpr-66-01-13. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31184944]

Brook I. Microbiology and principles of antimicrobial therapy for head and neck infections. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2007 Jun:21(2):355-91, vi [PubMed PMID: 17561074]

Baez-Pravia OV, Díaz-Cámara M, De La O, Pey C, Ontañón Martín M, Jimenez Hiscock L, Morató Bellido B, Córdoba Sánchez ÁL. Should we consider IgG hypogammaglobulinemia a risk factor for severe complications of Ludwig angina?: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine. 2017 Nov:96(47):e8708. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008708. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29381958]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWegrzyn TZ, Greenberg JS. Importance of the Physical Exam in Diagnosing Ludwig's Angina Without Access to Modern Imaging Modalities in the Developing World. Cureus. 2024 Nov:16(11):e74210. doi: 10.7759/cureus.74210. Epub 2024 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 39712743]

Minagawa S, Nagasaki K. Double-Tongue Sign in Ludwig's Angina. The American journal of medicine. 2024 Mar:137(3):e48-e49. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.11.017. Epub 2023 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 38042239]

Crespo AN, Chone CT, Fonseca AS, Montenegro MC, Pereira R, Milani JA. Clinical versus computed tomography evaluation in the diagnosis and management of deep neck infection. Sao Paulo medical journal = Revista paulista de medicina. 2004 Nov 4:122(6):259-63 [PubMed PMID: 15692720]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePak S, Cha D, Meyer C, Dee C, Fershko A. Ludwig's Angina. Cureus. 2017 Aug 21:9(8):e1588. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1588. Epub 2017 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 29062620]

Shockley WW. Ludwig angina: a review of current airway management. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 1999 May:125(5):600 [PubMed PMID: 10326825]

Ovassapian A, Tuncbilek M, Weitzel EK, Joshi CW. Airway management in adult patients with deep neck infections: a case series and review of the literature. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2005 Feb:100(2):585-589. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000141526.32741.CF. Epub [PubMed PMID: 15673898]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCandamourty R, Venkatachalam S, Babu MR, Kumar GS. Ludwig's Angina - An emergency: A case report with literature review. Journal of natural science, biology, and medicine. 2012 Jul:3(2):206-8. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.101932. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23225990]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSilva CM, Paixão J, Tavares PN, Baptista JP. Life-threatening complications of Ludwig's angina: a series of cases in a developed country. BMJ case reports. 2021 Apr 26:14(4):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-240429. Epub 2021 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 33906886]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLittle C. Ludwig's angina. Dimensions of critical care nursing : DCCN. 2004 Jul-Aug:23(4):153-4 [PubMed PMID: 15273479]

Rowe DP, Ollapallil J. Does surgical decompression in Ludwig's angina decrease hospital length of stay? ANZ journal of surgery. 2011 Mar:81(3):168-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05496.x. Epub 2010 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 21342390]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceParmar BD, Joshi KJ, Modi AD, Dave GP, Desai RS. Management of Ludwig's Angina at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Western Region of India. Cureus. 2022 Mar:14(3):e23311. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23311. Epub 2022 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 35464585]

Parhiscar A, Har-El G. Deep neck abscess: a retrospective review of 210 cases. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2001 Nov:110(11):1051-4 [PubMed PMID: 11713917]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGamble E, Chami P. Ludwig's angina. British dental journal. 2023 Nov:235(10):798. doi: 10.1038/s41415-023-6559-1. Epub 2023 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 38001201]