Introduction

Although generally considered a testicular neoplasm, with the vast majority occurring in men, Leydig cell tumors may occur in both sexes.[1] In men, Leydig cell tumors initially appear as testicular neoplasms. While accounting for a relatively small proportion of all cancer diagnoses in men, testicular neoplasms are the most common malignancy in men aged 15 to 44.[2] Testicular neoplasms are broadly categorized into germ cell tumors, which comprise approximately 95% of all testis cancers, and sex cord–stromal tumors, accounting for 2% to 5% in adults but 25% in children due to the lower incidence of germ cell tumors in the pediatric population.[3] Among sex cord–stromal tumors, Leydig cell tumors are the most common subtype (75%), originating from the specialized Leydig cells within the testicular interstitium between the seminiferous tubules. These tumors were first described by German zoologist and anatomist Franz von Leydig in 1870.[4][5][6][7] Leydig cell tumors are relatively rare, but they represent the most common type of nongerm cell testicular tumors.[8]

Leydig cells are essential for testosterone production, which is stimulated by luteinizing hormone, and are critical to the development of the male reproductive organs, such as the prostate and testes. Testosterone is responsible for the secondary male sexual characteristics, as well as increased muscle and bone mass, maintenance of libido, stimulation of erythropoiesis, and promotion of spermatogenesis.[4][9][10][11][12] Furthermore, Leydig cell tumors are typically benign, and malignancy is rare in children.[13][14][15][16] In adults, older estimates reported malignancy rates of 5% to 10%; recent large-scale study results report a considerably lower rate of approximately 2.5%.[3][17][18][19][20][21][22] However, other results indicate a malignancy rate of around 10% during follow-up.[23]

These tumors exhibit a bimodal age distribution, with incidence peaks in prepubertal boys (5 to 10 years) and adults (30 to 60 years).[3] Their inherent hormonal activity can lead to diverse clinical manifestations, including precocious puberty (62%), gynecomastia in adults (20%), or infertility (17% to 18%).[3][8][24] However, many Leydig cell tumors are discovered incidentally, such as during an infertility evaluation in men, in otherwise asymptomatic individuals.[4][25]

In women, Leydig cell tumors constitute less than 0.5% of all ovarian neoplasms.[1] Most occur around the time of menopause (70% to 85%), accompanied by increased androgen levels, causing hirsutism and virilization.[1] High serum testosterone levels (more than 3 times the reference range for age) cause an increase in masculinization symptoms.[1][26][27] Other sources of hyperandrogenism should be excluded, such as endocrinopathies, other hormonally active ovarian tumors, iatrogenic factors, and idiopathic causes.[1][27]

Diagnostic imaging in women may include transvaginal ultrasonography of the ovaries, pelvic MRI, and abdominal CT scans to evaluate the adrenal glands.[1][28] Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography can identify smaller foci of Leydig cell tumors.[1][29][30] Negative imaging results indicate that diagnostic laparoscopy is necessary.[1] In the absence of any apparent ovarian lesions, if no clear etiology is determined and adrenal causes of hyperandrogenism have been excluded, bilateral oophorectomy should be considered.[28][30][31][32][33] Treatment is surgical resection of the affected ovaries and fallopian tubes, and possible hysterectomy. Leydig cell malignancies in women are rare, with a poor prognosis due to the aggressive nature of these neoplasms.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Leydig cell tumors originate from Leydig cells, which are located between the seminiferous tubules of the testis and are responsible for testosterone secretion in response to luteinizing hormone.[34] The mechanism of Leydig cell oncogenesis remains poorly understood, although disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis, resulting in excessive luteinizing hormone stimulation, is thought to be a cause.[4]

Genetic mutations, both somatic and inherited, are involved:

- A heritable mutation in the fumarate hydratase gene has been identified in adults. This mutation activates the hypoxia-angiogenesis pathway, thereby promoting the growth of Leydig cell tumors.[35]

- A somatic activating mutation in the guanine nucleotide–binding protein α gene has been identified in several cases.[36]

- Fumarate hydratase inactivation, multiple copy number variations (including repeated, rearranged, or deleted sequences) without recurrent mutations, activation of the Wnt signaling pathway, and nuclear translocation of β-catenin all promote the malignant progression of Leydig cell tumors.[37][38]

Leydig cell tumors are strongly associated with male infertility, cryptorchidism, and gynecomastia, suggesting a role for testicular dysgenesis syndrome in their development.[39] Other factors that influence the development of Leydig cell tumors include inhibin, various growth factors, temperature changes, and Müllerian duct inhibitory factor.[40]

Epidemiology

Leydig cell tumors are considered rare, comprising 1% to 3% of all testicular neoplasms.[41][42][43] However, recent data have questioned this rarity, suggesting Leydig cell tumors may be more common. Some study results report an incidence as high as 22% of all small testicular nodules, with a mean prevalence of 26.6% among nonpalpable testicular masses.[17] This shift may be attributed to the routine use of ultrasonography, which enables the detection of small, nonpalpable, incidental testicular nodules that were previously undetectable.[17][39][44]

- Approximately 5% of patients with malignant Leydig cell tumors have a history of Klinefelter syndrome.[45][46]

- Leydig cell tumors are detected in 10% of young individuals with precocious puberty.[47] Unfortunately, physical changes associated with early puberty are irreversible.[14][15][24]

- The median age of presentation of all Leydig cell tumors is approximately 60 years.[37][48]

- The median age of presentation for benign Leydig cell tumors is 37.5 years.[7][37]

- The median age of presentation for malignant Leydig cell neoplasms is 68.5 years (27 to 80 years).[37][49][50]

Histopathology

Benign Leydig cell tumors typically present as small (<5 cm), well-circumscribed, solid masses within the testis. The cut surface is characteristically golden brown, a color imparted by abundant lipofuscin pigment. The color can range from yellow to gray-white depending on the lipid content.[7] While usually unilateral, bilateral cases are observed in approximately 3%.[51][52] Malignant Leydig cell tumors tend to be large (>5 cm) and demonstrate neoplastic infiltration outside the parenchyma of the testis into the adjacent epididymis, rete testis, or tunica.[53]

Microscopically, benign Leydig cell tumors commonly display nests or sheets of cells separated by delicate fibrovascular septa. Other, less common growth patterns include small clusters, trabeculae, pseudotubular, ribbon-like, spindled, or microcystic formations. The tumor cells are typically large and polygonal with abundant, eosinophilic, finely granular cytoplasm that may appear pale or clear due to lipid accumulation. Abundant lipofuscin pigment, appearing as golden yellow to brown cytoplasmic granules, is also characteristic.[7]

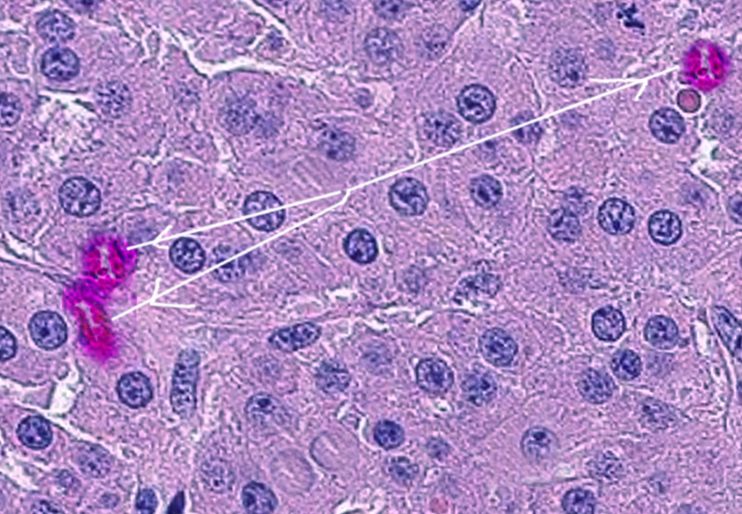

A distinctive feature of Leydig cell tumors, identified in approximately 30% to 35% of cases, is the presence of characteristic rod-shaped Reinke crystals within the cytoplasm. Reinke crystals are proteinaceous crystalline structures found exclusively in Leydig cells. They are composed of 5-nm filaments in a hexagonal pattern and fluoresce red when stained with eosin. Reinke crystals are refractile, come in various shapes (cylindrical, rectangular, or rhomboidal), and are typically arranged in a linear pattern.[54] See Image. Leydig Cell Tumor.

Immunohistochemistry can help differentiate Leydig cell masses from germ cell neoplasms and other testicular sex-cord stromal tumors. Leydig cell tumors stain strongly and diffusely positive for cytoplasmic inhibin.[4] This staining pattern makes inhibin a practical, sensitive, and distinctive marker to differentiate Leydig and Sertoli cell neoplasms (testicular sex-cord stromal tumors) from germ cell malignancies.[4][7][55] Leydig cell tumors, like Sertoli cell neoplasms, do not demonstrate positive immunostaining for alpha-fetoprotein, lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin.[4][55][56][57]

In addition to characteristic Reinke crystals, Leydig cell tumors typically stain strongly and diffusely positive for inhibin, calretinin, Melan-A, and steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1), but negatively for a Wilm tumor 1 (WT1) and cytokeratin.[4][55][58] Some Leydig cell tumors may exhibit focal, weak, or cytoplasmic staining for β-catenin, in contrast to the strongly positive nuclear staining observed in Sertoli cell neoplasms. Kiel-67 (Ki-67) is a nuclear protein antigen stained by the mindbomb homolog-1 (MIB-1) monoclonal antibody, produced by actively reproducing cells.[59][60][61] The higher the percentage of cells actively reproducing, the greater the risk of malignancy.[62][63][64] Various names refer to this percentage, including the Ki-67 or MIB-1 index, growth index, labeling index, or the proliferation index. An MIB-1 index of greater than 30% strongly favors malignancy, while an MIB-1 index of approximately 1.2% indicates a benign neoplasm.[53][57][58][62][58][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74]

In malignant Leydig cell tumors, inhibin staining is intense, while calretinin, Melan-A, CD99, and SF-1 stain positive. In contrast, WT1 and cytokeratin stains are negative. The MIB-1 index is high, and test results for oncogenic markers, including B-cell lymphoma 2 (bcl-2), Ki-67, and tumor protein 53 (p53), tend to be positive.[53][58][65][66][67][68][69][62] Positive test results for MDM2 oncogene amplification and increased copy number variations (without recurrent mutations) are more likely present in malignant Leydig cell neoplasms.[37][75][76]

Differentiating Leydig Cell Tumors From Leydig Cell Hyperplasia and Sertoli Cell Neoplasms

Leydig cell hyperplasia presents as bilateral, well-circumscribed, brown-yellowish nodules, ultimately leading to atrophy of the testis. There is an increased number of Leydig cells and nucleoli, accompanied by a decrease in lipofuscin.[77] The hyperplastic Leydig cells infiltrate the seminiferous tubules (containing only Sertoli cells) without obliterating or displacing them.[77] Hyperplasia lacks necrosis or hemorrhage and is considered a benign neoplasm. Microscopically, Leydig cell hyperplasia is characterized by large, eosinophilic, polygonal or round cells, decreased lipofuscin, and Reinke crystals in 25% to 40% of lesions. Urinary 17-ketosteroid levels are typically within the reference range.[77] Furthermore, Leydig cell hyperplasia should be considered in patients with Klinefelter syndrome who have negative tumor markers and multiple small bilateral testicular lesions.[78]

Leydig cell tumors may contain Reinke crystals, which is a definitive finding.[54] Leydig cell tumors will stain strongly positive for inhibin, calretinin, Melan-A, and SF-1, but weakly positive or negative for β-catenin, and will be negative for WT1 and cytokeratin.[4][23][55][58][79] Positive findings for bcl2, Ki-67, and p53 suggest malignancy, and a higher MIB-1 proliferation index suggests greater tumor aggressiveness.[53][65][66][68][80][81][82][83][84][85]

Sertoli cell tumors exhibit a distinct histological appearance compared to Leydig cell neoplasms.[54][86] Histologically, Sertoli cell tumors comprise proliferating cellular tubules with elongated nuclei arranged in a cord-like pattern. In contrast, Leydig cell tumors have a microscopic appearance of large, polygonal cells arranged in sheets.[7][54][86]

Sertoli cell neoplasms tend to exhibit positive, diffuse β-catenin nuclear staining and do not typically demonstrate Reinke crystals.[54][68][87] While some Leydig cell tumors may show weakly positive β-catenin staining, it's typically focal or cytoplasmic rather than the strongly positive, diffuse nuclear staining seen in Sertoli cell neoplasms.[23][68][86][88] In addition to β-catenin, Sertoli cell tumors will stain positively for WT1 and SF-1, but only weakly for inhibin, cytokeratin, and calretinin, while staining negatively for Melan-A.[4][68][79][89][90][91]

Microscopic features suggestive of Leydig cell tumor malignancy, particularly when 2 or more are found, include the following:

- Coagulative necrosis

- DNA aneuploidy

- Increased mitotic activity (>3–5 per 10 high-power fields) with atypical mitotic figures

- MIB-1

- Percentage of cells that stain positive for MIB-1

- High MIB-1 proliferation index

- Cells that stain positive for MIB-1

- Increased MIB-1 activity (mean activity of 18.6% compared to the benign Leydig cell tumors' mean activity of 1.2%) [53]

- Infiltrative surgical margins

- Lymphovascular invasion

- Marked cytologic and nuclear atypia

- Marked pleomorphism

- Necrotic foci [4][25][53][69][75][92]

The risk of metastases increases with the number of positive histopathologic risk factors.[93][94] No specific histopathological findings can definitively distinguish between malignant and benign Leydig cell neoplasms.[7][20][25][43][48][53][95] The most conclusive finding would be confirmation of a metastatic Leydig cell cancer on a surgical biopsy specimen.[49][69][96][97] In such cases, Reinke crystals, as detected by fine-needle aspiration or biopsy of the metastatic deposit, would be considered conclusive, as they are exclusively found in Leydig cell tumors.[49][54][69] Because the only definitive evidence of malignancy is the presence of metastasis, surveillance of patients with Leydig cell tumors is warranted, even when the initial histology is benign.[20]

History and Physical

Common Clinical Presentation

Like other testicular tumors, a painless intrascrotal mass or swelling is the most common clinical finding in patients with Leydig cell tumors.[98] However, the prevalence of palpable masses varies, with reports ranging from approximately 14% to 26% of patients.[8][44] Many Leydig cell tumors, particularly smaller ones, may be nonpalpable. Painless testicular swelling, precocious puberty, infertility, and gynecomastia (20%) are the most common presenting symptoms.[8][99] Other symptoms include breast tenderness, loss of libido, and erectile dysfunction.[8] Scrotal pain is a relatively uncommon symptom, reported in approximately 7% of patients.[44] Tumors are usually unilateral, and only 3% are bilateral.[25][51][100]

With the increased use of ultrasonography, especially in men with infertility, incidental testicular nodules are discovered more frequently.[17][22][101] Up to 22% of testicular masses smaller than 1.5 cm detected incidentally during an infertility evaluation were identified as Leydig cell tumors in recent studies.[17][102] Up to 49% of all incidentally discovered solid testicular nodules identified during ultrasonography, and as many as 48% of incidental masses found during an infertility evaluation, were Leydig cell tumors.[39][42][101][103]

Physical Examination

A complete physical examination should include palpating the affected and contralateral testicles, noting relative size, consistency, and any distinct intrinsic or extrinsic masses. Findings suggestive of a possible testicular Leydig cell cancer include large scrotal masses (>5 cm), older age, and the presence of metastatic lesions.[53] Moreover, hydroceles may also present as painless testicular swelling, but they are typically transilluminable and appear hypoechoic on ultrasonography.[104] Hydroceles may accompany a testicular tumor, so it is critical to obtain scrotal ultrasonography to detect underlying malignancy.[105]

Unique Hormonal Manifestations

A defining characteristic of Leydig cell tumors is their hormonal activity. These steroid-secreting tumors produce androgens (mainly testosterone) and estrogen, either directly or through the peripheral conversion of testosterone. This hormonal activity leads to clinical manifestations in many patients.

Prepubertal boys

- Androgen-secreting tumors typically present with precocious puberty, including early development of the penis and pubic hair, accelerated skeletal and muscle growth, advanced bone age, and skin changes.[24]

- Estrogen-secreting tumors in boys may lead to gynecomastia and breast tenderness, accompanied by a feminized hair distribution and underdeveloped genitalia.[106]

- Leydig cell tumors are consistently benign in prepubertal children.[13][14][15][16]

- Physical changes associated with precocious puberty are irreversible.[14][15][24]

Postpubertal adolescents and men

Hormonal imbalances are common, often characterized by elevated serum levels of testosterone or estradiol. Notably, testicular dysfunction and infertility can be a serious long-term consequence, particularly in estrogen-secreting Leydig cell tumors, due to impaired spermatogenesis.[4] Other clinical manifestations include:

- Cushing syndrome is a rare clinical manifestation of Leydig cell neoplasms.[95][107][108]

- Gynecomastia is the most common hormone-related presentation in men, occurring in about 20% (15% to 23%) of cases.[3][8]

- Other reported hormone-related presentations include breast tenderness, loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, impotence, and infertility.[51][109]

Associated Conditions

- Cryptorchidism (undescended testis) is more common in patients with Leydig cell tumors (15.6%) than in the general population, supporting the hypothesis that testicular dysgenesis syndrome may play a role in the development of testicular neoplasms.[39]

- Klinefelter syndrome (47, XXY karyotype) is a recognized risk factor for Leydig cell tumors.[3][78][110]

- Approximately 5% of patients with malignant Leydig cell tumors have a history of Klinefelter syndrome.[45][46]

- Characteristic ultrasound findings in patients with Klinefelter syndrome include severe testicular hypotrophy (average volume 2 mL) with a coarse or micronodular echotexture and increased bilateral symmetrical microlithiasis.[110]

- Histology often confirms these nodules as benign Leydig cell tumors or hyperplasia. For these patients, radical orchiectomy should be avoided in favor of testis-sparing surgery to preserve testosterone levels.[78]

- Patients with Klinefelter syndrome have an increased risk of extragonadal germ cell tumors, especially in the mediastinum.[110]

- Leydig cell tumors are strongly associated with male infertility, present in a substantial proportion of patients (48.2%) referred for infertility evaluation.[39][111]

Evaluation

Imaging

Scrotal ultrasound

This is the preferred initial imaging modality for evaluating patients with testicular disorders, such as unexplained pain, nodules, lumps, swellings, hydroceles, masses, or other nonspecific scrotal symptoms, due to its speed, broad availability, noninvasiveness, lack of ionizing radiation, painlessness, and cost-effectiveness.[17][112][113] Leydig cell tumors appear on ultrasound as well-defined, solid, homogeneous, hypoechoic intratesticular masses.[17][112][114] Benign ultrasonographic characteristics include a small size (≤7 mm) and a distinct margin from the adjacent parenchyma.[114] A hyperechoic peripheral rim may be observed, and intrinsic or peripheral rim hypervascularization may be present.[114][115] Microlithiasis is uncommon, but if present, it tends to be nongrouped (in contrast with seminoma, which may contain grouped microliths).

Color Doppler imaging reveals increased peripheral vascularity, often accompanied by a prominent feeding artery. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography demonstrates homogeneous enhancement from a centralized source; elastography shows increased stiffness.[17][116] However, Leydig cell tumors are often sonographically indistinguishable from more common malignant germ cell tumors. Any intratesticular mass should be presumed malignant until proven otherwise.[17][117]

Magnetic resonance imaging

This is not part of the routine; initial evaluation is recommended by the American Urological Association and the European Association of Urology guidelines for evaluating solid testicular masses, lumps, or nodules.[118][119][120] However, selective contrast-enhanced MRI may aid diagnosis in equivocal cases, particularly when considering testis-sparing surgery.[17][67][118][119][120][121][122][123][124][125][126] Typical findings for benign Leydig cell tumors include a markedly hypointense signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging, rapid and significant wash-in, and a prolonged washout.[67][121][122][123][124][127][128] Sustained enhancement of vascularized tissue suggests the presence of a tumor.[77] A fibrous capsule may appear hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging, while intralesional hyperintense signals may indicate scarring.[122]

MRI characteristics of malignant Leydig cell tumors compared to benign tumors include larger size, indistinct margins, weakly hypointense signals on T2-weighted imaging, lower apparent diffusion coefficient, inhomogeneous enhancement, and progressive but muted wash-in on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging.[116][121][129][130] The overall diagnostic accuracy of scrotal MRI is 93%.[121] The sensitivity of contrast-enhanced scrotal MRI to diagnose Leydig cell tumors is 89.47% with 95.65% specificity.[121] For malignant Leydig cell tumors, the sensitivity is 95.65% with a specificity of 80.95%.[121]

Laboratory Studies

Serum germ-cell tumor markers

These markers, including alpha-fetoprotein, quantitative beta-human chorionic gonadotropin, and lactate dehydrogenase, should be obtained whenever a testicular malignancy is suggested based on clinical or imaging findings.[117][131][132] Pure, isolated Leydig cell tumors present with serum tumor markers within the reference range.[7] This finding helps distinguish Leydig cell tumors and other testicular sex-cord stromal neoplasms from germ cell tumors, which present with elevated tumor marker levels.[7][19][117][131][132] Ultimately, histologic tissue examination and immunohistochemistry are required to definitively distinguish Leydig cell tumors from other testicular neoplasms. Notably, biopsy and fine needle aspiration are contraindicated for primary testicular tumors.

Hormone levels

These levels may be abnormal in patients with Leydig cell tumors who present with symptoms like unexplained infertility, precocious puberty, or gynecomastia.[24][99][111][133][134][135][136][137] In such cases, a complete serum hormonal profile, including follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, estradiol, estrogen, and testosterone, is essential.[24][111][134] Typical findings in Leydig cell tumors include elevated serum testosterone or elevated estradiol, which can suppress luteinizing and follicle-stimulating hormone levels, particularly in patients with precocious puberty.[7][24] Moreover, urinary ketosteroids, serum cortisol, dexamethasone suppression, or adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation testing may exclude other endocrinopathies, such as adrenocortical dysfunction.[138][139] However, endocrine dysfunction due to Leydig cell tumors is independent of the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal hormonal axis and is therefore unresponsive to dexamethasone suppression or adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation.[140][141][142]

Metastatic Evaluation

When a Leydig cell tumor is discovered, a metastatic evaluation is necessary, especially if microscopic findings suggest a malignancy.[43] This evaluation includes a CT scan of the abdomen, pelvis, and chest. The most common sites of metastases from malignant Leydig cell tumors are the inguinal, regional, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes (70%), the liver (45%), the lungs (40%), and bones (25%).[14][20][95] Long-term surveillance is recommended even for benign Leydig cell tumors, because metastatic lesions may appear years after surgical procedures.

Treatment / Management

The standard of care for an intratesticular mass is radical inguinal orchiectomy, particularly when malignancy is a consideration, because the sonographic appearance is indistinguishable from that of germ cell tumors.[119] Increasingly, testis-sparing surgery with intraoperative frozen sections is performed for small (<2 cm), benign-appearing testicular masses, including most benign Leydig cell tumors.[8][143][144] Testis-sparing surgery is considered a safe and effective alternative to radical inguinal orchiectomy, particularly when preserving testicular function and fertility are priorities, such as in patients with Klinefelter syndrome, younger patients with infertility, and men with a solitary testis.[14][15][43][46][143][145][146][147][148][149][150] A conservative testis-sparing approach is recommended only when serum germ cell tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin) are within the reference range. This approach is appropriate if a benign Leydig cell or similar benign neoplasm is suggested based on clinical findings (gynecomastia, elevated testosterone or estrogen, or infertility), the mass lesion is small (<2 cm), imaging studies do no demonstrate malignant characteristics, the contralateral testicle is normal, the intraoperative frozen section confirms benign histological features, and the patient agrees to long-term surveillance.[18][46][119][120](A1)

According to results from several studies, benign Leydig cell tumors treated with testis-sparing surgical procedures have not demonstrated local recurrence.[43][46][143][145][146][147][148][149][150][151][152] Active surveillance via clinical and radiological evaluation can be an option for small Leydig cell tumors without malignant characteristics, particularly in individuals with Klinefelter syndrome, a solitary testicle, and infertility. Notably, surgical intervention may not significantly improve fertility. Preoperative counseling about sperm banking is crucial, as patients with Leydig cell tumors have an increased risk for endocrine and spermatogenesis dysfunction even after tumor resection, necessitating prompt fertility preservation.[119][120] Preoperative decisions should also address the possibility of a radical orchiectomy depending on the frozen section results, even if testis-sparing surgery were originally intended, and the possible use of a testicular prosthesis.[119](A1)

Initial surgical procedures for solid testicular masses are often performed through an inguinal incision, even when testis-sparing surgery is planned, because conversion to a radical orchiectomy intraoperatively may be required. An inguinal incision prevents the spread of malignant testicular cells to the scrotum and its lymphatic drainage. This incision allows direct access to the testis and spermatic cord to the internal ring.[119][120][153] Scrotal incisions are not recommended when exploring solid scrotal masses.[118][119][120][154](A1)

While primary tumor biopsy before orchiectomy is contraindicated, an intraoperative frozen section can guide management. Frozen section evaluation may be considered when there are no signs of malignancy on imaging, the neoplasm is solitary, bilateral testicular tumors are present, the mass is small (<2 cm), and serum tumor marker results are negative. This approach avoids unnecessary orchiectomies in selected patients willing to undergo continued surveillance.[119][120][145][155][156] The intraoperative decision regarding testis-sparing surgery is based on mandatory frozen section examination of the tumor; evidence of malignancy requires radical orchiectomy.[119][120][157] (A1)

Ultimately, the final diagnosis is based primarily on immunohistochemical analysis of the resected tissue because the frozen section is accurate and reliable in diagnosing malignancy.[3][4][118][158][159][160][161][162][163][164][165] In the unlikely event that testis-sparing surgery is performed and the final diagnosis indicates a malignant Leydig cell tumor, an inguinal salvage radical orchiectomy is indicated. Unfortunately, due to the rarity of Leydig cell tumors and their similar presentation to germ cell neoplasms, many patients ultimately found to have Leydig cell tumors undergo initial radical inguinal orchiectomy. (A1)

Post-Orchiectomy Surveillance and Management

Leydig cell tumors are overwhelmingly benign, representing the most common nongerminomatous testicular tumor.[7] While the majority of Leydig cell tumors are cured after initial local excision, such as radical orchiectomy or testis-sparing surgery for smaller lesions, post-treatment surveillance is recommended.[118] When metastasis occurs, it is most often found in the retroperitoneal lymph nodes (70%), followed by the liver (45%), lungs (40%), and bones (25%).[44][48][166][167][168](B2)

Due to the very low incidence of malignant Leydig cell tumors, the optimal postoperative monitoring protocol has not been standardized. However, reasonable consensus suggests examination every 4 to 6 months during the first year after surgery, every 6 months for the second year, and annually for at least 5 years thereafter.[18][43] Long-term follow-up is warranted even in benign appearing Leydig cell tumors due to the potential for delayed metastases and metachronous contralateral neoplasms, observed in approximately 3% of cases.[8][20][39][106] These follow-up visits include physical examination, hormonal levels (including estradiol, estrogen, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and testosterone), and periodic chest, abdominal, and pelvic CT imaging.[55][169] Unfortunately, histopathologic evidence of malignancy may not be present at the time of orchiectomy, and some patients develop metastases years later.[45][95][170] Metastases have been reported up to 17 years after the original radical orchiectomy; however, approximately 82% of metastases occur within the first 5 years following the procedure.[8][171] (B2)

A retroperitoneal lymph node dissection and a longer surveillance interval are recommended for patients at higher risk for metastatic disease, such as older age at presentation, larger tumor size (>5 cm), multiple (>2) adverse histopathologic features, shorter duration of symptoms, positive surgical margins, evidence of tumor spread outside the testis, and the absence of endocrine manifestations.[8][45][172] With some metastases developing several years after surgery, and because histological and immunohistochemical testing is not definitive, surveillance for 10-15 years postoperatively should be considered, especially for Leydig cell tumors with malignant characteristics.[7][20][25][43][45][48][53][95][170][173](B2)

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection remains the standard of care for Leydig cell tumors that present with 2 or more histopathologic risk factors for malignancy. The procedure should be performed immediately after the radical orchiectomy.[7][21][45][119][174] A retroperitoneal lymph node dissection is not justified unless significant histopathologic or other risk factors are identified after orchiectomy.[175] Patients with Leydig cell tumors who were initially observed but later developed retroperitoneal metastases and underwent delayed retroperitoneal lymph node dissection often had worse outcomes than those who had an immediate lymph node dissection.[21][45] However, a few patients with low-volume retroperitoneal disease at presentation have had durable responses after retroperitoneal lymph node dissection.[45][176](B2)

Despite retroperitoneal lymph node dissection being the recommended treatment immediately following a diagnosis of Leydig cell tumor with malignant characteristics, only limited data are available on its effectiveness.[21][176] There is a general lack of effective treatment options because radiation and chemotherapy are relatively ineffective. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection is recognized for its efficacy and prognostic value, and can eradicate retroperitoneal micrometastases. Because this procedure may be life-saving, it remains the standard of care when 2 or more histopathological risk factors are identified, regardless of whether obvious metastasis is detected.[21][45][94][174][176][177][178](B2)

There are 3 different surgical approaches to retroperitoneal lymph node dissection: open, laparoscopic, and robotic, with equivalent efficacy.[179][180] Laparoscopic and robotic surgeries offer significantly reduced hospitalizations, improved cosmesis, and fewer complications than traditional open surgery.[181][182][183][184][185] However, laparoscopic and particularly robotic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection procedures are technically demanding and require extensive experience.[179][184][185][186][187][188] The American Urological Association and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that surgeons with extensive experience perform the procedures in high-volume centers.[179][184][185][189][190](A1)

Metastatic disease involving Leydig cell tumors generally demonstrates poor responsiveness to systemic chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and overall patient survival is poor. No standardized treatment guidelines exist for advanced disease.[4][21][169][191] While these modalities may offer palliative benefits or, rarely, achieve partial or complete remissions, surgical resection of metastases, particularly retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, is considered the primary and potentially curative treatment option, especially for micrometastatic disease.(B3)

Despite surgical interventions, patients with metastatic Leydig cell tumors have a poor prognosis, and no definitive standard treatment guidelines exist for advanced disease.[4][191] While these tumors are generally unresponsive to chemotherapy and radiation, there are anecdotal reports of complete remission with surgical resection of metastatic deposits as well as the use of bleomycin, cisplatin, and etoposide, and with local radiotherapy in low-volume, unresectable, metastatic disease.[8][168][169][192] The potential role of immunotherapy (immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors and inhibin vaccinations) and targeted treatments (like imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) is under investigation.[193][194](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for Leydig cell tumors varies based on the clinical presentation and diagnostic workup performed.[110][134] For patients presenting with hormonal manifestations such as gynecomastia or feminizing symptoms, consider the following conditions:

- Adrenal tumor/adrenal hyperplasia (functioning) [139]

- Drug adverse effects, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, marijuana, or spironolactone [195][196]

- Germ cell tumors [132]

- Hyperthyroidism [197]

- Klinefelter syndrome [110]

- Liver disease [198]

- Obesity [199]

For patients presenting with hypogonadism or infertility, consider the following conditions:

- Primary hypogonadism (eg, infection, Klinefelter syndrome, primary testicular failure, radiation, testicular trauma, or torsion)

- Secondary hypogonadism (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, Kallmann syndrome, and prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor) [7][110][111][131][132][200][201][202][203][204][205][206][207]

When a scrotal ultrasound identifies an intratesticular solid mass, the differential diagnosis should include the following:

- Germ cell tumors [131][132][208]

- Other sex cord-stromal tumors [7]

- Adult granulosa cell tumor

- Benign Leydig cell tumor

- Fibrothecoma

- Gonadoblastoma

- Large cell calcifying Sertoli cell tumor

- Mixed and unclassified sex cord–stromal tumors

- Myoid gonadal stromal tumor

- Sertoli cell tumor

- Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor [7]

- Other intratesticular masses

Prognosis

Endocrine dysfunction and infertility may persist even after the tumor resection.[209] For those presenting with hypogonadism, hormonal insufficiency may continue postorchiectomy, with a significant proportion of patients (40%), requiring ongoing testosterone replacement therapy.[133][210] Local recurrence after testis-sparing surgery occurs in 7% of patients.[8] Radical orchiectomy is curative in the vast majority of patients with benign Leydig cell tumors, with 5-year survival rates exceeding 90% and cancer-specific mortality rates of approximately 2%.[211][212][213] However, patients with Leydig cell malignancy have a markedly worse prognosis.

Patients diagnosed with malignant Leydig cell tumors without evidence of metastases have reported 1-year and 5-year survival rates of 98% and 91%, respectively.[45][212] Patients with malignant Leydig cell-proven metastatic disease have highly variable outcomes, with a reported median survival of approximately 2 years. However, this ranges from several months to over a decade in rare cases.[3][45][214]

Complications

Complications from Leydig cell tumors arise mainly from delays in diagnosis and treatment; these delays may result in gynecomastia, infertility, hypogonadism, or erectile dysfunction.[39] Delayed or inadequate treatment of malignant Leydig cell tumors may result in metastases and death.[215] Unfortunately, diagnostic delay in testicular cancer is common, with a mean delay of 26 weeks.[216] Patient-mediated delays are mainly due to lack of awareness, embarrassment, denial, fear of cancer, or emasculation.[217] Physician-mediated delay is most commonly due to initial misdiagnosis of the testicular tumor as an infection.[216]

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissections have a significant complication rate (up to 96% in one study) and a 30-day hospital readmission rate of 7%.[184][186][187][188] Smoking and concomitant vascular repair/reconstruction are risk factors.[184] For these complex and demanding surgeries, the American Urological Association advocates for the procedure, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that patients requiring retroperitoneal lymph node dissections be managed at a high-volume center of excellence.[189][190]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients diagnosed with Leydig cell tumors should be informed that a large majority of these tumors are benign, and orchiectomy is curative in almost all cases. Early detection and treatment can be vital for fertility preservation in men due to the detrimental effects of long-term estrogen exposure on spermatogenesis.[133] Patients considered for testis-sparing surgery must understand the risks and accept the requirement for prolonged surveillance. They must also be educated on the pros and cons of sperm banking, accept the possibility of a radical orchiectomy, and decide if they desire a testicular prosthesis. Informing patients that even after tumor excision, 40% of men presenting with hypogonadism may still require testosterone replacement therapy is essential.

Pearls and Other Issues

Pearls and other important information regarding Leydig cell cancer of the testis include the following:

- Approximately 1% (0.5% to 2%) of all adult neoplasms and 5% of all urological tumors are testicular in origin.[218]

- Of testicular tumors, 95% are germ cell tumors, and the rest, about 5%, are sex–cord stromal neoplasms, with benign Leydig cell tumors by far the most common (95%).[7]

- Of Leydig cell tumors, only about 2.5% in adults are malignant. (Historically, it was estimated at 10%, but recent large studies indicate an incidence of 2.5%.)[3][17][18][19][20][21][22]

- An intraoperative frozen section should be obtained during testis-sparing surgery, and a radical orchiectomy should be done if malignancy is suspected.[143][147][151]

- Immunohistochemistry markers for Leydig cell malignancy include the following:

- Negative immunostaining for β-catenin, cytokeratin, WT1, alpha-fetoprotein, lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin [4][55][56][57][58]

- Positive immunostaining for inhibin, calretinin, Melan-A, CD99, and SF-1, with a high MIB-1 index, and will tend to have positive oncogenic markers (bcl-2, Ki-67, and p53) [53][58][65][66][67][68][69][62]

- Leydig cell tumors (benign) exhibit a bimodal distribution, with an initial peak in the prepubertal age group, ranging from 4 to 10 years, and a second peak between 30 and 60 years.[3]

- Leydig cell tumors, like other testicular tumors, most commonly present as a painless testicular mass or swelling.[98]

- Leydig cell tumors definitively demonstrate malignancy by metastasizing.[170]

- Prolonged surveillance is necessary because late metastases from Leydig cell tumors have been reported even many years after orchiectomy.[7][43][48]

- Radical orchiectomy alone is generally curative for clinically benign Leydig cell tumors, but surveillance is recommended.[7][43][48][55]

- Retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy should be considered if pathology suggests a Leydig cell malignancy or if enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes are present.[48]

- Testis-sparing surgery is considered if the clinical findings suggest a Leydig cell tumor, preoperative testicular tumor marker levels are within normal limits, and the tumor is less than 2.5 cm.[143][147]

- The only effective treatment for malignant Leydig cell tumors besides radical orchiectomy is retroperitoneal lymph node dissection because they are resistant to chemotherapy and radiation.[21][169]

- There are no reported cases of malignant Leydig cell tumors in the prepubertal pediatric population.[13][14][15][16]

- Due to the hormonal production of Leydig cell tumors, patients may present with symptoms of gynecomastia, breast tenderness, precocious puberty, infertility, hypogonadism, or erectile dysfunction.[3][8][99]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of Leydig cell malignancies can be particularly challenging, especially given the tumor's relative rarity and highly variable presentation. Generally, the longer the delay in diagnosis, the worse the outcomes; therefore, an educated interprofessional healthcare team is beneficial in diagnosing and managing small testicular masses and suspected Leydig cell tumors.[118][119][219] Primary care and emergency department clinicians should consider ultrasonography as a routine extension of the physical examination for any patient with unilateral scrotal swelling, a solid intrascrotal lump, or unexplained testicular pain.[113] They should refer patients with equivocal ultrasound results to a urologist for further evaluation and treatment.

Primary care physicians and endocrinologists should consider Leydig cell tumors in the differential diagnosis of male infertility, hypogonadism, and particularly gynecomastia.[7][134] Specialty-trained nursing staff in urology and oncology can be invaluable throughout the diagnosis and management of these tumors, providing counseling and patient education, assisting during procedures, and facilitating surveillance examinations. The entire interprofessional team, comprising primary care clinicians, endocrinologists, urologists, radiologists, oncologists, radiation therapists, sonographers, and nurses, should communicate and collaborate to enhance patient care, facilitate early diagnosis, and optimize outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Klimek M, Radosz P, Lemm M, Szanecki W, Dudek A, Pokładek S, Piwowarczyk M, Poński M, Cichoń B, Kajor M, Witek A. Leydig cell ovarian tumor - clinical case description and literature review. Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review. 2020 Sep:19(3):140-143. doi: 10.5114/pm.2020.99578. Epub 2020 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 33100950]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePark JS, Kim J, Elghiaty A, Ham WS. Recent global trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality. Medicine. 2018 Sep:97(37):e12390. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012390. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30213007]

Mooney KL, Kao CS. A Contemporary Review of Common Adult Non-germ Cell Tumors of the Testis and Paratestis. Surgical pathology clinics. 2018 Dec:11(4):739-758. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2018.07.002. Epub 2018 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 30447839]

Al-Agha OM, Axiotis CA. An in-depth look at Leydig cell tumor of the testis. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2007 Feb:131(2):311-7 [PubMed PMID: 17284120]

Ober WB, Sciagura C. Leydig, Sertoli, and Reinke: three anatomists who were on the ball. Pathology annual. 1981:16 Pt 1():1-13 [PubMed PMID: 7036067]

Zirkin BR, Papadopoulos V. Leydig cells: formation, function, and regulation. Biology of reproduction. 2018 Jul 1:99(1):101-111. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy059. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29566165]

Kapoor M, Leslie SW. Testicular Sex Cord–Stromal Tumors. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644342]

Fankhauser CD, Grogg JB, Hayoz S, Wettstein MS, Dieckmann KP, Sulser T, Bode PK, Clarke NW, Beyer J, Hermanns T. Risk Factors and Treatment Outcomes of 1,375 Patients with Testicular Leydig Cell Tumors: Analysis of Published Case Series Data. The Journal of urology. 2020 May:203(5):949-956. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000705. Epub 2019 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 31845841]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNassar GN, Leslie SW. Physiology, Testosterone. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252384]

Grande G, Barrachina F, Soler-Ventura A, Jodar M, Mancini F, Marana R, Chiloiro S, Pontecorvi A, Oliva R, Milardi D. The Role of Testosterone in Spermatogenesis: Lessons From Proteome Profiling of Human Spermatozoa in Testosterone Deficiency. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2022:13():852661. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.852661. Epub 2022 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 35663320]

Smith LB, Walker WH. The regulation of spermatogenesis by androgens. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2014 Jun:30():2-13. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.02.012. Epub 2014 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 24598768]

Walker WH. Androgen Actions in the Testis and the Regulation of Spermatogenesis. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2021:1288():175-203. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-77779-1_9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34453737]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMéndez-Gallart R, Bautista A, Estevez E, Barreiro J, Evgenieva E. Leydig Cell Testicular Tumour Presenting as Isosexual Precocious Pseudopuberty in a 5 Year-old Boy with No Palpable Testicular Mass. Clinical pediatric endocrinology : case reports and clinical investigations : official journal of the Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology. 2010 Jan:19(1):19-23. doi: 10.1297/cpe.19.19. Epub 2010 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 23926374]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJ.S. Valla for the Group D'Etude en Urologie Pédiatrique. Testis-sparing surgery for benign testicular tumors in children. The Journal of urology. 2001 Jun:165(6 Pt 2):2280-3 [PubMed PMID: 11379598]

Ross JH. Prepubertal testicular tumors. Urology. 2009 Jul:74(1):94-9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.12.036. Epub 2009 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 19428066]

Brosman SA. Testicular tumors in prepubertal children. Urology. 1979 Jun:13(6):581-8 [PubMed PMID: 377749]

Maxwell F, Savignac A, Bekdache O, Calvez S, Lebacle C, Arama E, Garrouche N, Rocher L. Leydig Cell Tumors of the Testis: An Update of the Imaging Characteristics of a Not So Rare Lesion. Cancers. 2022 Jul 27:14(15):. doi: 10.3390/cancers14153652. Epub 2022 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 35954321]

Bozzini G, Picozzi S, Gadda F, Colombo R, Decobelli O, Palou J, Colpi G, Carmignani L. Long-term follow-up using testicle-sparing surgery for Leydig cell tumor. Clinical genitourinary cancer. 2013 Sep:11(3):321-4. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2012.12.008. Epub 2013 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 23317518]

Suardi N, Strada E, Colombo R, Freschi M, Salonia A, Lania C, Cestari A, Carmignani L, Guazzoni G, Rigatti P, Montorsi F. Leydig cell tumour of the testis: presentation, therapy, long-term follow-up and the role of organ-sparing surgery in a single-institution experience. BJU international. 2009 Jan:103(2):197-200. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08016.x. Epub 2008 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 18990169]

Di Tonno F, Tavolini IM, Belmonte P, Bertoldin R, Cossaro E, Curti P, D'Incà G, Fandella A, Guaitoli P, Guazzieri S, Mazzariol C, North-Eastern Uro-Oncological Group, Italy. Lessons from 52 patients with leydig cell tumor of the testis: the GUONE (North-Eastern Uro-Oncological Group, Italy) experience. Urologia internationalis. 2009:82(2):152-7. doi: 10.1159/000200790. Epub 2009 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 19322000]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMosharafa AA, Foster RS, Bihrle R, Koch MO, Ulbright TM, Einhorn LH, Donohue JP. Does retroperitoneal lymph node dissection have a curative role for patients with sex cord-stromal testicular tumors? Cancer. 2003 Aug 15:98(4):753-7 [PubMed PMID: 12910519]

Leonhartsberger N, Ramoner R, Aigner F, Stoehr B, Pichler R, Zangerl F, Fritzer A, Steiner H. Increased incidence of Leydig cell tumours of the testis in the era of improved imaging techniques. BJU international. 2011 Nov:108(10):1603-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10177.x. Epub 2011 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 21631694]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKitagawa Y, De Biase D, Ricci C, Cornejo KM, Fiorentino M, Collins K, Idrees MT, Colecchia M, Ulbright TM, Acosta AM. β-Catenin alterations in testicular Leydig cell tumour: a immunohistochemical and molecular analysis. Histopathology. 2024 Jul:85(1):75-80. doi: 10.1111/his.15175. Epub 2024 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 38530207]

Kota AS, Sharma L, Ejaz S. Precocious Puberty. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31335033]

Kim I, Young RH, Scully RE. Leydig cell tumors of the testis. A clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases and review of the literature. The American journal of surgical pathology. 1985 Mar:9(3):177-92 [PubMed PMID: 3993830]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGlintborg D, Altinok ML, Petersen KR, Ravn P. Total testosterone levels are often more than three times elevated in patients with androgen-secreting tumours. BMJ case reports. 2015 Jan 23:2015():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204797. Epub 2015 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 25616651]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSharma A, Welt CK. Practical Approach to Hyperandrogenism in Women. The Medical clinics of North America. 2021 Nov:105(6):1099-1116. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2021.06.008. Epub 2021 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 34688417]

Mourinho Bala N, Aragüés JM, Guerra S, Brito D, Valadas C. Ovarian Leydig Cell Tumor: Cause of Virilization in a Postmenopausal Woman. The American journal of case reports. 2021 Aug 27:22():e933126. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.933126. Epub 2021 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 34449760]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePrassopoulos V, Laspas F, Vlachou F, Efthimiadou R, Gogou L, Andreou J. Leydig cell tumour of the ovary localised with positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Gynecological endocrinology : the official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology. 2011 Oct:27(10):837-9. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2010.521263. Epub 2011 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 21668318]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTreglia G, Espeli V, Giovanella L. Leydig cell tumor incidentally detected by fused FDG-PET/MRI. Endocrine. 2015 Dec:50(3):819-20. doi: 10.1007/s12020-015-0538-5. Epub 2015 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 25636443]

Kong J, Park YM, Choi YS, Cho S, Lee BS, Park JH. Diagnosis of an indistinct Leydig cell tumor by positron emission tomography-computed tomography. Obstetrics & gynecology science. 2019 May:62(3):194-198. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2019.62.3.194. Epub 2019 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 31139598]

Chavez TF, Singh M, Avadhani V, Leonis R. Leydig tumor in normal sized ovaries causing clitoromegaly: A case report. Gynecologic oncology reports. 2024 Apr:52():101345. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2024.101345. Epub 2024 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 38435349]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLangevin TL, Maynard K, Dewan A. Bilateral microscopic Leydig cell ovarian tumors in the postmenopausal woman. BMJ case reports. 2020 Dec 22:13(12):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-236427. Epub 2020 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 33370966]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAladamat N, Tadi P. Histology, Leydig Cells. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310467]

Carvajal-Carmona LG, Alam NA, Pollard PJ, Jones AM, Barclay E, Wortham N, Pignatelli M, Freeman A, Pomplun S, Ellis I, Poulsom R, El-Bahrawy MA, Berney DM, Tomlinson IP. Adult leydig cell tumors of the testis caused by germline fumarate hydratase mutations. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2006 Aug:91(8):3071-5 [PubMed PMID: 16757530]

Libé R, Fratticci A, Lahlou N, Jornayvaz FR, Tissier F, Louiset E, Guibourdenche J, Vieillefond A, Zerbib M, Bertherat J. A rare cause of hypertestosteronemia in a 68-year-old patient: a Leydig cell tumor due to a somatic GNAS (guanine nucleotide-binding protein, alpha-stimulating activity polypeptide 1)-activating mutation. Journal of andrology. 2012 Jul-Aug:33(4):578-84. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.111.013441. Epub 2011 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 22016347]

Rizzo NM, Sholl LM, Idrees MT, Cheville JC, Gupta S, Cornejo KM, Miyamoto H, Hirsch MS, Collins K, Acosta AM. Comparative molecular analysis of testicular Leydig cell tumors demonstrates distinct subsets of neoplasms with aggressive histopathologic features. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2021 Oct:34(10):1935-1946. doi: 10.1038/s41379-021-00845-3. Epub 2021 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 34103665]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcCarroll SA,Altshuler DM, Copy-number variation and association studies of human disease. Nature genetics. 2007 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 17597780]

Pozza C, Pofi R, Tenuta M, Tarsitano MG, Sbardella E, Fattorini G, Cantisani V, Lenzi A, Isidori AM, Gianfrilli D, TESTIS UNIT. Clinical presentation, management and follow-up of 83 patients with Leydig cell tumors of the testis: a prospective case-cohort study. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2019 Aug 1:34(8):1389-1403. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez083. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31532522]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLejeune H, Habert R, Saez JM. Origin, proliferation and differentiation of Leydig cells. Journal of molecular endocrinology. 1998 Feb:20(1):1-25 [PubMed PMID: 9513078]

Masur Y, Steffens J, Ziegler M, Remberger K. [Leydig cell tumors of the testis--clinical and morphologic aspects]. Der Urologe. Ausg. A. 1996 Nov:35(6):468-71 [PubMed PMID: 9064885]

Carmignani L, Gadda F, Gazzano G, Nerva F, Mancini M, Ferruti M, Bulfamante G, Bosari S, Coggi G, Rocco F, Colpi GM. High incidence of benign testicular neoplasms diagnosed by ultrasound. The Journal of urology. 2003 Nov:170(5):1783-6 [PubMed PMID: 14532776]

Carmignani L, Salvioni R, Gadda F, Colecchia M, Gazzano G, Torelli T, Rocco F, Colpi GM, Pizzocaro G. Long-term followup and clinical characteristics of testicular Leydig cell tumor: experience with 24 cases. The Journal of urology. 2006 Nov:176(5):2040-3; discussion 2043 [PubMed PMID: 17070249]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRuf CG, Sanatgar N, Isbarn H, Ruf B, Simon J, Fankhauser CD, Dieckmann KP. Leydig-cell tumour of the testis: retrospective analysis of clinical and therapeutic features in 204 cases. World journal of urology. 2020 Nov:38(11):2857-2862. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03079-1. Epub 2020 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 31960106]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAzizi M, Aydin AM, Cheriyan SK, Peyton CC, Montanarella M, Gilbert SM, Sexton WJ. Therapeutic strategies for uncommon testis cancer histologies: teratoma with malignant transformation and malignant testicular sex cord stromal tumors. Translational andrology and urology. 2020 Jan:9(Suppl 1):S91-S103. doi: 10.21037/tau.2019.09.08. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32055490]

Laclergerie F, Mouillet G, Frontczak A, Balssa L, Eschwege P, Saussine C, Larré S, Cormier L, Vuillemin AT, Kleinclauss F. Testicle-sparing surgery versus radical orchiectomy in the management of Leydig cell tumors: results from a multicenter study. World journal of urology. 2018 Mar:36(3):427-433. doi: 10.1007/s00345-017-2151-0. Epub 2017 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 29230496]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceUrban MD, Lee PA, Plotnick LP, Migeon CJ. The diagnosis of Leydig cell tumors in childhood. American journal of diseases of children (1960). 1978 May:132(5):494-7 [PubMed PMID: 645676]

Bertram KA, Bratloff B, Hodges GF, Davidson H. Treatment of malignant Leydig cell tumor. Cancer. 1991 Nov 15:68(10):2324-9 [PubMed PMID: 1913469]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLai N, Zeng X, Li M, Shu J. Leydig cell tumor with lung metastasis diagnosed by lung biopsy. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2015:8(10):12972-6 [PubMed PMID: 26722493]

Lam JS, Borczuk AC, Franklin JR. Metastatic Leydig cell tumor of the testicle in a young African American male. The Canadian journal of urology. 2003 Dec:10(6):2074-6 [PubMed PMID: 14704114]

Al-Zubi M, Araydah M, Al Sharie S, Qudsieh SA, Abuorouq S, Qasim TS. Bilateral testicular Leydig cell hyperplasia presented incidentally: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2022 Jan:90():106733. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.106733. Epub 2021 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 34968979]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCrook D, Cary C. Bilateral Leydig Cell Tumors in Klinefelter Patient: A Case Report. Urology. 2020 Aug:142():e29-e31. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.03.051. Epub 2020 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 32305546]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCheville JC, Sebo TJ, Lager DJ, Bostwick DG, Farrow GM. Leydig cell tumor of the testis: a clinicopathologic, DNA content, and MIB-1 comparison of nonmetastasizing and metastasizing tumors. The American journal of surgical pathology. 1998 Nov:22(11):1361-7 [PubMed PMID: 9808128]

Planinić A, Marić T, Bojanac AK, Ježek D. Reinke crystals: Hallmarks of adult Leydig cells in humans. Andrology. 2022 Sep:10(6):1107-1120. doi: 10.1111/andr.13201. Epub 2022 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 35661438]

Genov PP, Georgieva DP, Koleva GV, Kolev NH, Dunev VR, Stoykov BA. Management of Leydig cell tumors of the testis-a case report. Urology case reports. 2020 Jan:28():101064. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2019.101064. Epub 2019 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 31754603]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVukina J, Chism DD, Sharpless JL, Raynor MC, Milowsky MI, Funkhouser WK. Metachronous Bilateral Testicular Leydig-Like Tumors Leading to the Diagnosis of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (Adrenogenital Syndrome). Case reports in pathology. 2015:2015():459318. doi: 10.1155/2015/459318. Epub 2015 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 26351608]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDieckmann KP, Simonsen-Richter H, Kulejewski M, Anheuser P, Zecha H, Isbarn H, Pichlmeier U. Serum Tumour Markers in Testicular Germ Cell Tumours: Frequencies of Elevated Levels and Extents of Marker Elevation Are Significantly Associated with Clinical Parameters and with Response to Treatment. BioMed research international. 2019:2019():5030349. doi: 10.1155/2019/5030349. Epub 2019 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 31275973]

Gheorghisan-Galateanu AA. Leydig cell tumors of the testis: a case report. BMC research notes. 2014 Sep 18:7():656. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-656. Epub 2014 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 25230718]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSun X, Kaufman PD. Ki-67: more than a proliferation marker. Chromosoma. 2018 Jun:127(2):175-186. doi: 10.1007/s00412-018-0659-8. Epub 2018 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 29322240]

Andrés-Sánchez N, Fisher D, Krasinska L. Physiological functions and roles in cancer of the proliferation marker Ki-67. Journal of cell science. 2022 Jun 1:135(11):. pii: jcs258932. doi: 10.1242/jcs.258932. Epub 2022 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 35674256]

Menon SS, Guruvayoorappan C, Sakthivel KM, Rasmi RR. Ki-67 protein as a tumour proliferation marker. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2019 Apr:491():39-45. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.01.011. Epub 2019 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 30653951]

Spyratos F, Ferrero-Poüs M, Trassard M, Hacène K, Phillips E, Tubiana-Hulin M, Le Doussal V. Correlation between MIB-1 and other proliferation markers: clinical implications of the MIB-1 cutoff value. Cancer. 2002 Apr 15:94(8):2151-9 [PubMed PMID: 12001111]

Ali AE, Morgen EK, Geddie WR, Boerner SL, Massey C, Bailey DJ, da Cunha Santos G. Classifying B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma by using MIB-1 proliferative index in fine-needle aspirates. Cancer cytopathology. 2010 Jun 25:118(3):166-72. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20075. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20544708]

Yamamoto E, Tomita N, Sakata S, Tsuyama N, Takeuchi K, Nakajima Y, Miyashita K, Tachibana T, Takasaki H, Tanaka M, Hashimoto C, Koharazawa H, Fujimaki K, Taguchi J, Harano H, Motomura S, Ishigatsubo Y. MIB-1 labeling index as a prognostic factor for patients with follicular lymphoma treated with rituximab plus CHOP therapy. Cancer science. 2013 Dec:104(12):1670-4. doi: 10.1111/cas.12288. Epub 2013 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 24112697]

Kudo T, Kamiie J, Aihara N, Doi M, Sumi A, Omachi T, Shirota K. Malignant Leydig cell tumor in dogs: two cases and a review of the literature. Journal of veterinary diagnostic investigation : official publication of the American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians, Inc. 2019 Jul:31(4):557-561. doi: 10.1177/1040638719854791. Epub 2019 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 31248354]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHekimgil M, Altay B, Yakut BD, Soydan S, Ozyurt C, Killi R. Leydig cell tumor of the testis: comparison of histopathological and immunohistochemical features of three azoospermic cases and one malignant case. Pathology international. 2001 Oct:51(10):792-6 [PubMed PMID: 11881732]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhu J, Luan Y, Li H. Management of testicular Leydig cell tumor: A case report. Medicine. 2018 Jun:97(25):e11158. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011158. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29924022]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAcosta AM, Colecchia M, Comperat E, Cornejo KM, Gill AJ, Gupta S, Cheville JC, Idrees MT, Kao CS, Maclean F, Matoso A, Raspollini MR, Michalova K, Mugica MR, Tickoo SK, Tsuzuki T, Ulbright TM, Williamson SR, Siegmund S, Sholl LM, Gonzalez-Peramato P, Berney DM. Assessment and classification of sex cord-stromal tumours of the testis: recommendations from the testicular sex cord-stromal tumour (TESST) group, an Expert Panel of the Genitourinary Pathology Society (GUPS) and International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP). Histopathology. 2025 Jun 18:():. doi: 10.1111/his.15482. Epub 2025 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 40528632]

Sengupta S, Chatterjee U, Sarkar K, Chatterjee S, Kundu A. Leydig cell tumor: a report of two cases with unusual presentation. Indian journal of pathology & microbiology. 2010 Oct-Dec:53(4):796-8. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.72096. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21045421]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAbramovich CM, Prayson RA. MIB-1 labeling indices in benign, aggressive, and malignant meningiomas: a study of 90 tumors. Human pathology. 1998 Dec:29(12):1420-7 [PubMed PMID: 9865827]

Shimura T, Kofunato Y, Okada R, Yashima R, Okada K, Araki K, Hosouchi Y, Kuwano H, Takenoshita S. MIB-1 labeling index, Ki-67, is an indicator of invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Molecular and clinical oncology. 2016 Aug:5(2):317-322 [PubMed PMID: 27446570]

Cameron RI, Maxwell P, Jenkins D, McCluggage WG. Immunohistochemical staining with MIB1, bcl2 and p16 assists in the distinction of cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia from tubo-endometrial metaplasia, endometriosis and microglandular hyperplasia. Histopathology. 2002 Oct:41(4):313-21 [PubMed PMID: 12383213]

Ciaputa R, Nowak M, Madej JA, Poradowski D, Janus I, Dziegiel P, Gorzynska E, Kandefer-Gola M. Inhibin-α, E-cadherin, calretinin and Ki-67 antigen in the immunohistochemical evaluation of canine and human testicular neoplasms. Folia histochemica et cytobiologica. 2014:52(4):326-34. doi: 10.5603/FHC.a2014.0036. Epub 2014 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 25511291]

McCluggage WG, Shanks JH, Arthur K, Banerjee SS. Cellular proliferation and nuclear ploidy assessments augment established prognostic factors in predicting malignancy in testicular Leydig cell tumours. Histopathology. 1998 Oct:33(4):361-8 [PubMed PMID: 9822927]

Colecchia M, Bertolotti A, Paolini B, Giunchi F, Necchi A, Paganoni AM, Ricci C, Fiorentino M, Dagrada GP. The Leydig cell tumour Scaled Score (LeSS): a method to distinguish benign from malignant cases, with additional correlation with MDM2 and CDK4 amplification. Histopathology. 2021 Jan:78(2):290-299. doi: 10.1111/his.14225. Epub 2020 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 32757426]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNecchi A, Bratslavsky G, Shapiro O, Elvin JA, Vergilio JA, Killian JK, Ngo N, Ramkissoon S, Severson E, Hemmerich AC, Ali SM, Chung JH, Reddy P, Miller VA, Schrock AB, Gay LM, Ross JS, Jacob JM. Genomic Features of Metastatic Testicular Sex Cord Stromal Tumors. European urology focus. 2019 Sep:5(5):748-755. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2019.05.012. Epub 2019 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 31147264]

Carucci LR, Tirkes AT, Pretorius ES, Genega EM, Weinstein SP. Testicular Leydig's cell hyperplasia: MR imaging and sonographic findings. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2003 Feb:180(2):501-3 [PubMed PMID: 12540460]

Sterbis J, E-Nunu T. Leydig cell hyperplasia in the setting of Klinefelter syndrome. BMJ case reports. 2015 Jul 24:2015():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-209805. Epub 2015 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 26209412]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEmerson RE, Ulbright TM. The use of immunohistochemistry in the differential diagnosis of tumors of the testis and paratestis. Seminars in diagnostic pathology. 2005 Feb:22(1):33-50 [PubMed PMID: 16512598]

Tateishi U, Hasegawa T, Beppu Y, Kawai A, Moriyama N. Prognostic significance of grading (MIB-1 system) in patients with myxoid liposarcoma. Journal of clinical pathology. 2003 Aug:56(8):579-82 [PubMed PMID: 12890805]

Jensen V, Sørensen FB, Bentzen SM, Ladekarl M, Nielsen OS, Keller J, Jensen OM. Proliferative activity (MIB-1 index) is an independent prognostic parameter in patients with high-grade soft tissue sarcomas of subtypes other than malignant fibrous histiocytomas: a retrospective immunohistological study including 216 soft tissue sarcomas. Histopathology. 1998 Jun:32(6):536-46 [PubMed PMID: 9675593]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSofiadis A, Tani E, Foukakis T, Kjellman P, Skoog L, Höög A, Wallin G, Zedenius J, Larsson C. Diagnostic and prognostic potential of MIB-1 proliferation index in thyroid fine needle aspiration biopsy. International journal of oncology. 2009 Aug:35(2):369-74 [PubMed PMID: 19578751]

La Rosa S. Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Predictive Role of Ki67 Proliferative Index in Neuroendocrine and Endocrine Neoplasms: Past, Present, and Future. Endocrine pathology. 2023 Mar:34(1):79-97. doi: 10.1007/s12022-023-09755-3. Epub 2023 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 36797453]

Hellgren LS, Stenman A, Paulsson JO, Höög A, Larsson C, Zedenius J, Juhlin CC. Prognostic Utility of the Ki-67 Labeling Index in Follicular Thyroid Tumors: a 20-Year Experience from a Tertiary Thyroid Center. Endocrine pathology. 2022 Jun:33(2):231-242. doi: 10.1007/s12022-022-09714-4. Epub 2022 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 35305239]

Torp SH, Lindboe CF, Grønberg BH, Lydersen S, Sundstrøm S. Prognostic significance of Ki-67/MIB-1 proliferation index in meningiomas. Clinical neuropathology. 2005 Jul-Aug:24(4):170-4 [PubMed PMID: 16033133]

Grogg J, Schneider K, Bode PK, Kranzbühler B, Eberli D, Sulser T, Lorch A, Beyer J, Hermanns T, Fankhauser CD. Sertoli Cell Tumors of the Testes: Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of Outcomes in 435 Patients. The oncologist. 2020 Jul:25(7):585-590. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0692. Epub 2020 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 32043680]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZhang C, Ulbright TM. Nuclear Localization of β-Catenin in Sertoli Cell Tumors and Other Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors of the Testis: An Immunohistochemical Study of 87 Cases. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2015 Oct:39(10):1390-4. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000455. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26034868]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChang H, Guillou F, Taketo MM, Behringer RR. Overactive beta-catenin signaling causes testicular sertoli cell tumor development in the mouse. Biology of reproduction. 2009 Nov:81(5):842-9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.077446. Epub 2009 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 19553598]

Nielsen K, Jacobsen GK. Malignant Sertoli cell tumour of the testis. An immunohistochemical study and a review of the literature. APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 1988 Aug:96(8):755-60 [PubMed PMID: 2458122]

Herman D, Mantle P. Immunohistochemical Review of Leydig Cell Lesions in Ochratoxin A-Treated Fischer Rats and Controls. Toxins. 2019 Aug 20:11(8):. doi: 10.3390/toxins11080480. Epub 2019 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 31434192]

Zhao C, Barner R, Vinh TN, McManus K, Dabbs D, Vang R. SF-1 is a diagnostically useful immunohistochemical marker and comparable to other sex cord-stromal tumor markers for the differential diagnosis of ovarian sertoli cell tumor. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists. 2008 Oct:27(4):507-14. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31817c1b0a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18753972]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStoop H, Kirkels W, Dohle GR, Gillis AJ, den Bakker MA, Biermann K, Oosterhuis W, Looijenga LH. Diagnosis of testicular carcinoma in situ '(intratubular and microinvasive)' seminoma and embryonal carcinoma using direct enzymatic alkaline phosphatase reactivity on frozen histological sections. Histopathology. 2011 Feb:58(3):440-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03767.x. Epub 2011 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 21323965]

Rove KO, Maroni PD, Cost CR, Fairclough DL, Giannarini G, Harris AK, Schultz KA, Cost NG. Pathologic Risk Factors for Metastatic Disease in Postpubertal Patients With Clinical Stage I Testicular Stromal Tumors. Urology. 2016 Nov:97():138-144. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.06.066. Epub 2016 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 27538802]

Nicolai N, Necchi A, Raggi D, Biasoni D, Catanzaro M, Piva L, Stagni S, Maffezzini M, Torelli T, Faré E, Giannatempo P, Pizzocaro G, Colecchia M, Salvioni R. Clinical outcome in testicular sex cord stromal tumors: testis sparing vs. radical orchiectomy and management of advanced disease. Urology. 2015 Feb:85(2):402-6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.10.021. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25623702]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchwarzman MI, Russo P, Bosl GJ, Whitmore WF Jr. Hormone-secreting metastatic interstitial cell tumor of the testis. The Journal of urology. 1989 Mar:141(3):620-2 [PubMed PMID: 2918605]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBiemer J, Pambuccian SE, Barkan GA. Fine needle aspiration diagnosis of metastatic Leydig cell tumor. Report of a case and review of the literature. Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology. 2019 Jul-Aug:8(4):220-229. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2019.02.001. Epub 2019 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 31272604]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHanda U, Sood T, Punia RS. Testicular Leydig cell tumor diagnosed on fine needle aspiration. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2010 Sep:38(9):682-4. doi: 10.1002/dc.21306. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20737589]

Markou A, Vale J, Vadgama B, Walker M, Franks S. Testicular leydig cell tumor presenting as primary infertility. Hormones (Athens, Greece). 2002 Oct-Dec:1(4):251-4 [PubMed PMID: 17018455]

Zeuschner P, Veith C, Linxweiler J, Stöckle M, Heinzelbecker J. Two Years of Gynecomastia Caused by Leydig Cell Tumor. Case reports in urology. 2018:2018():7202560. doi: 10.1155/2018/7202560. Epub 2018 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 30112247]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePetkovic V, Salemi S, Vassella E, Karamitopoulou-Diamantis E, Meinhardt UJ, Flück CE, Mullis PE. Leydig-cell tumour in children: variable clinical presentation, diagnostic features, follow-up and genetic analysis of four cases. Hormone research. 2007:67(2):89-95 [PubMed PMID: 17047343]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCorcioni B, Brandi N, Marasco G, Gaudiano C, De Cinque A, Ciccarese F, Ercolino A, Schiavina R, Brunocilla E, Renzulli M, Golfieri R. Multiparametric ultrasound for the diagnosis of Leydig cell tumours in non-palpable testicular lesions. Andrology. 2022 Oct:10(7):1387-1397. doi: 10.1111/andr.13233. Epub 2022 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 35842907]

Isidori AM, Pozza C, Gianfrilli D, Giannetta E, Lemma A, Pofi R, Barbagallo F, Manganaro L, Martino G, Lombardo F, Cantisani V, Franco G, Lenzi A. Differential diagnosis of nonpalpable testicular lesions: qualitative and quantitative contrast-enhanced US of benign and malignant testicular tumors. Radiology. 2014 Nov:273(2):606-18. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14132718. Epub 2014 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 24968192]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLagabrielle S, Durand X, Droupy S, Izard V, Marcelli F, Huyghe E, Ferriere JM, Ferretti L. Testicular tumours discovered during infertility workup are predominantly benign and could initially be managed by sparing surgery. Journal of surgical oncology. 2018 Sep:118(4):630-635. doi: 10.1002/jso.25203. Epub 2018 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 30196556]

Huzaifa M, Moreno MA. Hydrocele. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644551]

Ben Kridis W, Lajnef M, Khmiri S, Boudawara O, Slimen MH, Boudawara T, Khanfir A. Testicular leydig cell tumor revealed by hydrocele. Urology case reports. 2021 Mar:35():101520. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2020.101520. Epub 2020 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 33318945]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLuckie TM, Danzig M, Zhou S, Wu H, Cost NG, Karaviti L, Venkatramani R. A Multicenter Retrospective Review of Pediatric Leydig Cell Tumor of the Testis. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 2019 Jan:41(1):74-76. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000001124. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29554024]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePapadimitris C, Alevizaki M, Pantazopoulos D, Nakopoulou L, Athanassiades P, Dimopoulos MA. Cushing syndrome as the presenting feature of metastatic Leydig cell tumor of the testis. Urology. 2000 Jul 1:56(1):153 [PubMed PMID: 10869651]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKnyrim K, Higi M, Hossfeld DK, Seeber S, Schmidt CG. Autonomous cortisol secretion by a metastatic Leydig cell carcinoma associated with Klinefelter's syndrome. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 1981:100(1):85-93 [PubMed PMID: 7016888]

Ojewola RW, Aranmolate RA. Leydig Cell Testicular Tumor Presenting as Bilateral Breast Masses: A Case Report. Journal of the West African College of Surgeons. 2023 Oct-Dec:13(4):119-122. doi: 10.4103/jwas.jwas_54_23. Epub 2023 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 38449551]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLos E, Leslie SW, Ford GA. Klinefelter Syndrome. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29493939]

Leslie SW, Soon-Sutton TL, Khan MAB. Male Infertility. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32965929]

Benn M, Southgate SJ, Leslie SW. Ultrasound of the Urinary Tract. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571002]

Kühn AL, Scortegagna E, Nowitzki KM, Kim YH. Ultrasonography of the scrotum in adults. Ultrasonography (Seoul, Korea). 2016 Jul:35(3):180-97. doi: 10.14366/usg.15075. Epub 2016 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 26983766]

Maxwell F, Izard V, Ferlicot S, Rachas A, Correas JM, Benoit G, Bellin MF, Rocher L. Colour Doppler and ultrasound characteristics of testicular Leydig cell tumours. The British journal of radiology. 2016 Jun:89(1062):20160089. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20160089. Epub 2016 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 27072392]

Grand T, Hermann AL, Gérard M, Arama E, Ouerd L, Garrouche N, Rocher L. Precocious puberty related to Leydig cell testicular tumor: the diagnostic imaging keys. European journal of medical research. 2022 May 12:27(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s40001-022-00692-1. Epub 2022 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 35550623]

Rocher L, Ramchandani P, Belfield J, Bertolotto M, Derchi LE, Correas JM, Oyen R, Tsili AC, Turgut AT, Dogra V, Fizazi K, Freeman S, Richenberg J. Incidentally detected non-palpable testicular tumours in adults at scrotal ultrasound: impact of radiological findings on management Radiologic review and recommendations of the ESUR scrotal imaging subcommittee. European radiology. 2016 Jul:26(7):2268-78. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4059-7. Epub 2015 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 26497666]

Gaddam SJ, Bicer F, Chesnut GT. Testicular Cancer. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33085306]

Stephenson A, Eggener SE, Bass EB, Chelnick DM, Daneshmand S, Feldman D, Gilligan T, Karam JA, Leibovich B, Liauw SL, Masterson TA, Meeks JJ, Pierorazio PM, Sharma R, Sheinfeld J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Early Stage Testicular Cancer: AUA Guideline. The Journal of urology. 2019 Aug:202(2):272-281. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000318. Epub 2019 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 31059667]

Stephenson A, Bass EB, Bixler BR, Daneshmand S, Kirkby E, Marianes A, Pierorazio PM, Sharma R, Spiess PE. Diagnosis and Treatment of Early-Stage Testicular Cancer: AUA Guideline Amendment 2023. The Journal of urology. 2024 Jan:211(1):20-25. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000003694. Epub 2023 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 37707243]

Patrikidou A, Cazzaniga W, Berney D, Boormans J, de Angst I, Di Nardo D, Fankhauser C, Fischer S, Gravina C, Gremmels H, Heidenreich A, Janisch F, Leão R, Nicolai N, Oing C, Oldenburg J, Shepherd R, Tandstad T, Nicol D. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Testicular Cancer: 2023 Update. European urology. 2023 Sep:84(3):289-301. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2023.04.010. Epub 2023 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 37183161]

Manganaro L, Vinci V, Pozza C, Saldari M, Gianfrilli D, Pofi R, Bernardo S, Cantisani V, Lenzi A, Scialpi M, Catalano C, Isidori AM. A prospective study on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of testicular lesions: distinctive features of Leydig cell tumours. European radiology. 2015 Dec:25(12):3586-95. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3766-4. Epub 2015 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 25981218]

Fernández GC, Tardáguila F, Rivas C, Trinidad C, Pesqueira D, Zungri E, San Miguel P. Case report: MRI in the diagnosis of testicular Leydig cell tumour. The British journal of radiology. 2004 Jun:77(918):521-4 [PubMed PMID: 15151977]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAngulo Hervías E, Riazuelo Fantova G, Escartín Martínez I, Cañón Merayo R. [MRI for the diagnosis of Leydig cell testicular tumors]. Archivos espanoles de urologia. 2007 Jan-Feb:60(1):75-7 [PubMed PMID: 17408178]