Introduction

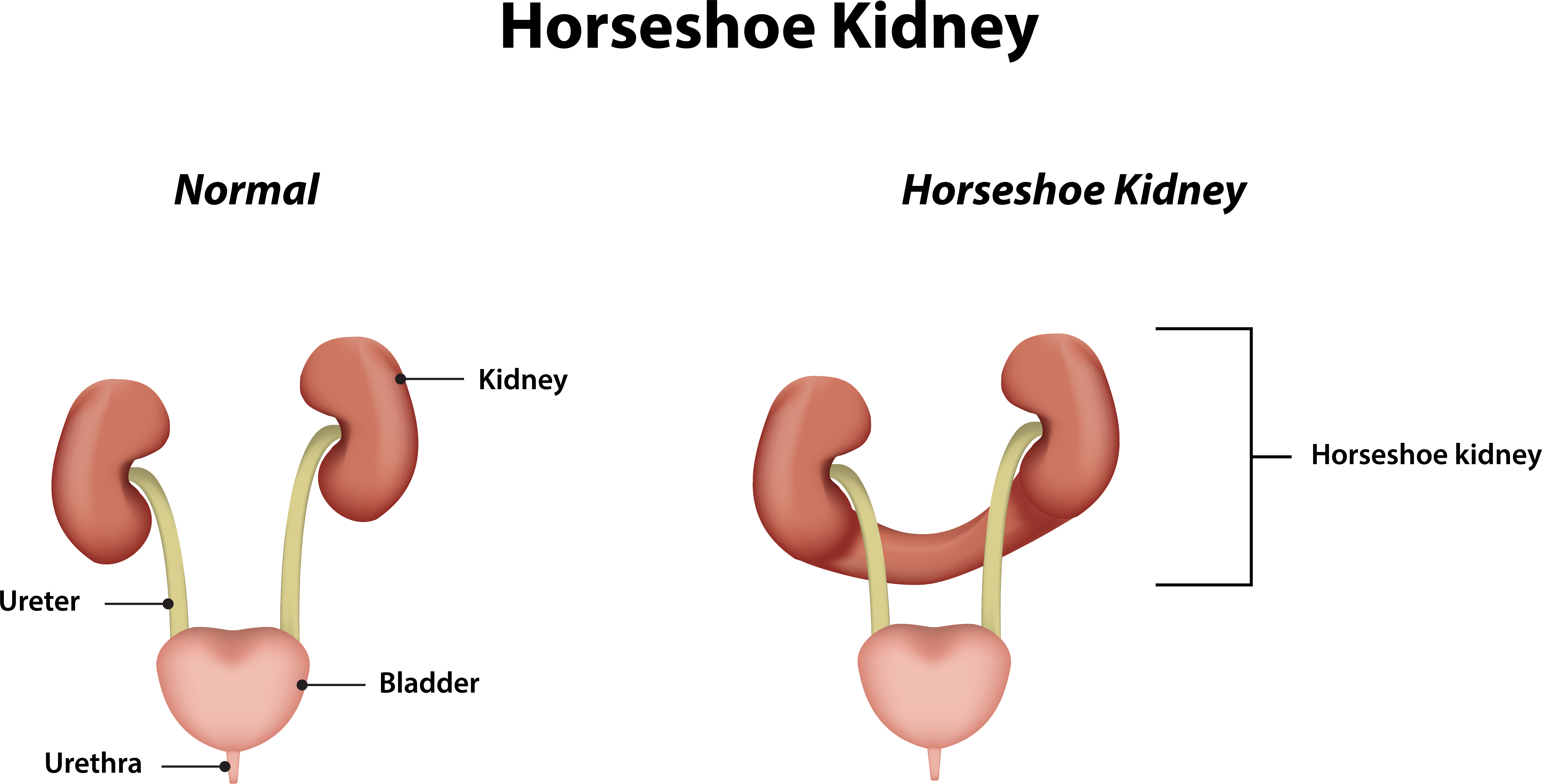

Horseshoe kidney is the most common congenital renal fusion anomaly, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 500 live births.[1] As first described in autopsy studies by da Carpi in 1522, a horseshoe kidney is characterized by the fusion of the lower poles of the kidneys across the midline. This anomaly is typically associated with vascular, rotational, and positional anatomical abnormalities, typically resulting in a U-shaped unitary renal unit configuration in the midabdomen, positioned lower in position than normal kidneys.[1][2] The isthmus, which connects the 2 renal masses, typically (80%) consists of functioning renal parenchyma with its own blood supply, but it may also be composed of fibrous tissue.[3][4]

The connecting isthmus is located between the lower poles in over 90% of cases, but it may occur elsewhere in a small minority.[3][5][6][7][8] The kidneys are malrotated, with their lower poles fused and their collecting systems facing anteriorly.[2] As they descend to the bladder, the ureters pass anterior to the isthmus, typically located immediately below the inferior mesenteric artery. Abnormal courses of the ureters predispose them to ureteral obstruction and stasis.[2]

Horseshoe kidneys demonstrate a significant variation in the origin and number of renal arteries and veins.[5][6][9] Vascularization is mainly dependent on where the renal ascent is terminated in development. In a study involving 90 horseshoe kidneys, 387 separate arteries were identified.[6] Nevertheless, the regular intrarenal segmental, non-collateral arterial vascular pattern remains, and ligation or division of any renal arteries results in ischemic segmental renal ischemia or necrosis.[10] The incidence of renal vein anomalies in horseshoe kidneys is also high at 23%.[6]

The natural history is generally benign; however, affected individuals are at increased risk for complications such as ureteropelvic junction obstruction, hydronephrosis, nephrolithiasis, urinary tract infections, vesicoureteral reflux, and renal malignancies, such as renal cell carcinoma, transitional cell cancer, and Wilms tumor in children.[3] The overall risk of a renal malignancy in a horseshoe kidney is about 3 to 4 times higher than in the general population.[11][12] There is also a higher risk of traumatic injury to the kidney due to its lower position, anterior location, and lack of protection from the rib cage, although such injuries are rarely reported.[1][13][14][15][16][17][18]

Chronic kidney disease and progression to end-stage renal disease are more common in this population, likely due to the high prevalence of associated genitourinary anomalies and complications.[3][14] The abnormal vasculature and collecting system anatomy can complicate the presentation and management of disease, particularly surgical procedures.[1][13] Extrarenal anomalies, including gastrointestinal and vertebral malformations, are also more frequent in affected individuals, especially in pediatric populations.[19]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of horseshoe kidneys is rooted in abnormal embryologic development, specifically the fusion of the metanephric blastemas at their lower poles before the completion of renal capsule formation.[1][20] This fusion typically occurs between the 4th and 6th weeks of gestation.[1][3][20] As the fused kidneys attempt to ascend from the pelvis to their normal lumbar position, their upward migration is arrested by the inferior mesenteric artery, resulting in the characteristic low anterior position and midline fusion (isthmus) observed in horseshoe kidneys.[3]

The kidneys are typically located in the retroperitoneum between the transverse processes of T12 and L3, with the left kidney slightly superior to the right.[21] The upper poles are positioned slightly medially and posteriorly relative to the lower poles.[21] Horseshoe kidneys are different in three main ways—location, orientation, and vasculature.[2][21]

During development, the kidneys align with their hilums anterior and parallel.[22] As development proceeds, the kidneys normally ascend and separate while rotating 90° medially, with the renal hilums now facing each other across the midline.[22][23][24] When this process is interrupted by the presence of an isthmus between the lower poles of the kidneys, further ascent, migration, and rotation cannot occur.

The ascent of a horseshoe kidney is often described as being held back by the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery at L3; however, horseshoe kidneys can also be found lower in the abdomen and pelvis. The upper poles and calyces now diverge and are more lateral than the lower poles. During 6 to 8 weeks of development, the renal ascent is coupled with a 90° medial rotation.[23][24] Due to the persistent isthmus, however, horseshoe kidneys experience malrotation. Consequently, the ureters should either pass over the isthmus or down the anterior surface of the kidneys, which can cause urinary drainage problems and stasis.[9][25]

Horseshoe kidneys also show a great variation in the origin and number of renal arteries and veins.[5][6][9] These variations are largely dependent on where the renal ascent terminates during development. In a study involving 90 horseshoe kidneys, 387 arteries were identified.[6] Despite this, the normal intrarenal vascular segmental pattern remains, and the ligation or division of any of these arteries results in ischemic segmental renal ischemia or necrosis due to their poor collateral arterial supply.[10] The incidence of renal vein anomalies in horseshoe kidneys is also high at 23%.[6]

A teratogenic component is believed to cause abnormal migration of posterior nephrogenic cells to the inferior medial aspect of the lower poles, which then fuse to form the isthmus across the midline where the 2 kidneys are closest.[1][26][27] Environmental factors contributing to the development of a horseshoe kidney include alterations in the intrauterine environment. Teratogenic drugs such as thalidomide, alcohol consumption, and poor glycemic control cause an increase in incidence. Structural factors include flexion or rotation of the caudal spine and narrowed arterial forks during migration.[1][6][28][29][30][31]

Genetic factors also contribute to the development of horseshoe kidneys, as it is classified among the congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Mutations in genes, such as PAX2, HNF1B, Shh, and WT1, as well as disruptions in cell signaling and migration, have been implicated.[1][32][33]

Epidemiology

The incidence of horseshoe kidneys is approximately 1 in 500 or 0.25% in the general population, with a male preponderance of 2:1.[6][13] Horseshoe kidneys are associated with chromosomal disorders, such as Edward syndrome (trisomy 18) at about 67%, Turner syndrome at 20%, and Down syndrome at 1%.[1][34][35][36][37][38][39]

However, chromosomal microarray analyses found that the frequency of abnormal results in fetuses with horseshoe kidneys was no different than that observed in the general population.[40] Horseshoe kidney variants are higher in children as a concomitant presentation in newborns with multiple congenital variants, some of which are not compatible with long-term survival.[1][6][34][35][36]

History and Physical

Horseshoe kidneys are often asymptomatic and are typically identified incidentally. However, when symptoms occur, they are generally nonspecific, with a study showing that the most common presenting complaints in children with a horseshoe kidney include abdominal pain and symptoms of a urinary tract infection (UTI).[16]

Flank pain, hematuria, nephrolithiasis, hydronephrosis, or abdominal discomfort may prompt evaluation in adults. There is also an increased risk of associated congenital anomalies, including genitourinary and extrarenal malformations, particularly in pediatric populations.[14] Horseshoe kidneys are more prone to injury from blunt abdominal trauma due to their anterior, unprotected position, with possible traumatic compression over the lumbar vertebrae, possibly aggravated during a motor vehicle accident due to pressure from the seat belt, dash, and steering wheel.[41][42]

Physical examination may reveal a palpable mass in the lower abdomen in children or thinner patients. Costovertebral angle tenderness may also be present. Horseshoe kidneys are most often identified on imaging performed for unrelated reasons. As many as 85% of patients with horseshoe kidneys have associated anomalies involving the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or skeletal systems, and up to two-thirds have associated genitourinary abnormalities, including the following:

- Approximately 4% of male patients have either hypospadias or a cryptorchid testis.[43]

- Approximately 7% of female patients have a bicornate uterus or a septated vagina.[44]

- Kidney cancers are 3 to 4 times more common overall.[11][12]

- Nephrolithiasis is present in about 36% of patients, due to low urinary volume, stasis, hypercalciuria, and hypocitraturia.[45][46][47]

- Ureteral duplications are found in 10% of cases.[43][48]

- Ureteropelvic junction obstructions may be found in up to 33% of patients.[43][49][50]

- Vesicoureteral reflux is present in about 50% of patients with horseshoe kidneys.[18][51]

Evaluation

Horseshoe kidneys can be identified using most abdominal imaging modalities. The diagnosis of a horseshoe kidney is most commonly made using either ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scans.[52] Magnetic resonance imaging and CT are the most effective modalities for clearly demonstrating the anatomy, detecting accessory vasculature, and visualizing surrounding structures, which may be affected.[6][52][53]

Optimally, a CT urogram—abdomen and pelvis CT imaging performed without and then with intravenous (IV) contrast—should be performed, allowing for the identification of urolithiasis, urinary blockages, and ureteropelvic junction obstructions. Magnetic resonance imaging examinations can be used where ionizing radiation should be avoided or in patients who cannot tolerate standard IV contrast media.

Horseshoe kidneys may occasionally be identified on plain radiography through visualization of the perinephric fat in association with an altered renal axis. The lower poles are more medial and closer together than normal, with the kidneys sitting lower in the abdomen and the upper poles wider apart.[52]

Nuclear medicine radionuclide renal scans can help differentiate actual blockages from passively dilated systems and assist in the diagnosis of ureteropelvic junction obstructions.[54][55] Voiding cystourethrograms can be used to identify vesicoureteral reflux, which is more common in patients with horseshoe kidneys than in the general population.[51] In rare cases of horseshoe kidney and associated polycystic kidney disease, genetic testing (PKD1 (16p13.3) and PKD2 (4q21)) becomes a key component of the evaluation.[56]

Treatment / Management

Most patients with horseshoe kidneys are asymptomatic and do not require intervention. However, regular monitoring is recommended, as these individuals are at an increased risk of complications such as UTIs, nephrolithiasis, hydronephrosis, and chronic kidney disease. Management should be individualized based on the presence and type of complications.[1][14][57][58] Medical management includes regular surveillance of blood pressure, urinalysis for proteinuria, and assessment of renal function, given the increased risk of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in this population.[58][59]

Nephrolithiasis

Nephrolithiasis is managed according to stone size and location. Shock wave lithotripsy or ureteroscopy is preferred for small stones, whereas percutaneous nephrolithotomy is indicated for larger calculi or those refractory to shock wave lithotripsy and ureteroscopy; open surgery is reserved for cases with significant anatomic abnormalities and cases refractory to minimally invasive treatment.[60][61][62][63][64][65](B3)

Shockwave lithotripsy is less effective in horseshoe kidneys due to difficulty localizing the energy for pelvic stones and poor stone fragment clearance due to impaired renal drainage.[66] Larger renal stones, those greater than 2.5 cm, or those that do not allow ureteroscopic approaches, can be removed through minimally invasive percutaneous or mini-percutaneous surgery.[67][68](B3)

Guidelines recommend that patients with horseshoe kidneys who develop stones undergo a 24-hour urine analysis for stone prevention and receive appropriate prophylactic treatment.[62][69][70][71][72][73][74] Successful prevention requires a high level of patient compliance on a long-term basis; however, all patients with horseshoe kidneys who develop stones should be offered nephrolithiasis preventive testing, as surgical stone treatment is often far more complex than in anatomically normal patients with urolithiasis.[58][59](B3)

Urinary Tract Infections

UTIs should be managed with standard culture-specific antibiotic therapy, and evaluation for underlying structural abnormalities is warranted, especially in cases of recurrent infections.[1][14][58][59]

Surgical and Interventional Management

Surgical and interventional management is reserved for symptomatic or complicated cases. Pre-procedural imaging, such as CT scans, is essential during the workup for any procedure due to the horseshoe kidney's highly variable vascular anatomy, including multiple renal arteries frequently arising from the aorta or iliac vessels, and common aberrant veins.[75] This complex vasculature increases the risk of intraoperative complications and should be carefully delineated before surgical intervention.

Additionally, pre-procedural imaging is essential to visualize adjacent colon segments to reduce the risk of incidental bowel injury.[75] Computerized 3-dimensional image modeling can help dramatically improve surgical decision-making, facilitate preoperative treatment planning, assist in tailoring the surgical approach, and help develop a surgical strategy in complex anatomical cases, such as horseshoe kidneys, that require surgical intervention.[76][77][78][79][80](B3)

Indications for Surgical Intervention

Indications for surgical intervention include symptomatic ureteropelvic junction obstruction, recurrent or complicated UTIs, ureterolithiasis or nephrolithiasis not amenable to conservative management, significant symptomatic vesicoureteral reflux with cortical thinning, or a nonfunctioning renal moiety.[51][58][81] Treatment options for ureteropelvic junction obstruction include percutaneous endopyelotomy, laparoscopic or robotic pyeloplasty, or open pyeloplasty, based on anatomical considerations and surgical expertise.[59]

Significant or symptomatic hydronephrosis may require surgical correction. Total or partial nephrectomy is considered for nonfunctioning, malignant, or severely diseased renal moieties.[82] Historically, surgical division of the isthmus was frequently performed, but this is no longer routinely recommended due to the increased risk of bleeding, fistula formation, infection, and leakages.[83][84] The kidneys ultimately return to their original location regardless.(B3)

The use of perpendicular, alternating, biplanar fluoroscopy has been described to assist in the percutaneous approach to stones in patients with a horseshoe kidney. The technique allows for better visualization of stone position and the complex renal anatomy during percutaneous surgery without requiring patient repositioning or standard fluoroscopy, reducing patient radiation exposure and shortening overall operating time.[83]

Managing renal cancers in patients with a horseshoe kidney is essentially the same as in normal individuals, except surgical procedures are far more complex due to the varied vascular anatomy, unusual renal location, and other factors. Traditionally, the surgical approach has been open surgery. Laparoscopic and robotic techniques can also be used, although these procedures are more complex than in anatomically normal kidneys.[84][85] Regardless of their number, all renal arteries in horseshoe kidneys are end-arteries, and damage to them results in renal ischemia.(B3)

Intraperitoneal laparoscopic and robotic techniques for heminephrectomy, pyelolithotomy, and pyeloplasty in patients with a horseshoe kidney have been successfully performed, demonstrating good outcomes and minimal complications in experienced centers.[86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The horseshoe kidney is 1 form of renal fusion abnormality. The other 2 main types are crossed-fusion renal ectopia and a fused pelvic kidney.

In crossed renal ectopia, both kidneys are positioned on the same side of the body, with 1 ureter crossing the midline to drain into the bladder. In contrast, in a fused pelvic kidney, there is a single renal mass that is drained by 2 ureters that do not cross the midline.[94] Failure of renal ascent results in a kidney located in the pelvis, which may be mistaken for a horseshoe kidney, especially if both kidneys are low-lying. However, there is no fusion between the kidneys, the renal axes are not divergent, and the vascular supply is often anomalous.[99][100]

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease presents as bilateral renal enlargement with multiple cysts that can mimic the mass effect and abnormal renal contour of a horseshoe kidney, but cystic changes and family history help distinguish the 2 entities.[56][101][102][101]

In children, a renal mass may represent Wilms tumor rather than a congenital anomaly.[103] The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends thorough imaging and laboratory evaluation to differentiate Wilms tumor from benign renal conditions and other masses.[104]

Prognosis

Approximately one-third of all patients with horseshoe kidneys remain completely asymptomatic, and the renal anomalies are often found incidentally during imaging. An isolated finding of an incidentally discovered, asymptomatic horseshoe kidney is generally considered benign and requires no treatment.[51] Symptomatic patients may require specific therapy based on their disorder, circumstances, and findings.

Patients with horseshoe kidneys have a higher incidence of ureteropelvic junction obstructions—the most common complication—followed by hydronephrosis, nephrolithiasis, UTIs, and vesicoureteral reflux than the general population.[3]

Complications

The intrinsic anatomical and genetic defects associated with horseshoe kidneys predispose individuals with this anomaly to several urological sequelae due to the associated ureteric obstruction, impaired urinary drainage, and other factors.[52][105]

Approximately two-thirds of patients develop associated complications, including hydronephrosis, nephrolithiasis, ureteropelvic junction obstructions, UTIs, and vesicoureteral reflux, which is higher than in the general population.[2][9][25][55][51][61][62] Ureteropelvic junction obstruction is the most common complication, affecting up to one-third of patients.[49][55]

Horseshoe kidneys also have an increased frequency of common kidney cancers, including transitional and renal cell malignancies (each is 3-4 times more common), Wilms tumor (twice as frequently), and a huge increase in the incidence of some sporadic cancerous neoplasms, such as carcinoid (62-82 times).[6][45][58][106][107][108][109][110] Renal cell cancer is the most common kidney malignancy found in patients with horseshoe kidneys and accounts for 50% of all renal neoplasms in these patients.[110][111][112]

Primary renal lymphoma in association with a horseshoe kidney has also been reported and should be included among the possible neoplasms that patients may develop.[113] A renal biopsy should be performed when imaging provides atypical findings, a renal mass, or when the outcome can impact treatment and clinical decision-making.[113]

The risk and difficulty of renal biopsies in patients with horseshoe kidneys are increased due to structural abnormalities and anatomical variances. Still, renal biopsies can be accomplished through precise positioning with abdominal ultrasonographic or CT image guidance.[114]

Over 50% of individuals with horseshoe kidneys who become symptomatic have either ureteropelvic junction obstruction or vesicoureteral reflux.[59]

Meta-analysis suggests that 36% of patients with a horseshoe kidney develop nephrolithiasis at some stage.[45]

Due to their ectopic position, horseshoe kidneys are also particularly susceptible to blunt abdominal trauma, as they can be fractured or compressed against the lumbar vertebrae.[1][13][14][15][16][17][18]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education regarding horseshoe kidney focuses on the monitoring and prevention of complications through lifestyle modifications and ongoing patient counseling. Patients should be educated about their increased risk for UTIs, nephrolithiasis, ureteropelvic junction obstruction, and, in rare cases, chronic kidney disease and malignancy.[1][14][19][57]

Key prevention strategies include maintaining adequate hydration, performing 24-hour urine testing to reduce stone formation risk, promptly recognizing and treating UTIs, and conducting regular follow-up with urinalysis and renal function monitoring to detect early signs of proteinuria, hypertension, or renal scarring.[1][14]

Patients should be counseled to avoid activities that increase the risk of abdominal trauma, given the abnormal position and aberrant vascular supply of the horseshoe kidney.[57] Lifestyle modifications such as a balanced diet low in salt and animal protein may help reduce stone risk, and blood pressure should be monitored regularly. Education should also address the importance of adherence to follow-up imaging and laboratory assessments, as early detection of complications is critical for preserving renal function.[1][14][19][57]

Children and adults should be evaluated for associated genitourinary and extrarenal anomalies, and families should be informed about the potential for syndromic associations, especially in pediatric cases.[1][19]

Pearls and Other Issues

Symphysiotomy, or division of the fused isthmus, was previously recommended during pyeloplasty in patients with a horseshoe kidney. However, this practice has changed due to the increased risk of infection, fistulas, leakages, and bleeding.[115] Notably, the kidneys return to their original location after surgery, so symphysiotomy is no longer routinely recommended.

Renal transplantation can be successfully performed using donors with horseshoe kidneys.[116][117][118][119][120][121] There is no consensus on separating the isthmus, but several techniques have been described and used successfully.[117]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with horseshoe kidneys are at an increased risk of ureteropelvic junction obstructions, nephrolithiasis, vesicoureteral reflux, UTIs, transitional cell cancers, and malignant renal tumors. Most cases are discovered serendipitously during imaging for unrelated problems, often with ultrasound. A CT urogram—abdomen and pelvis CT imaging performed without and then with IV contrast—is the basis for a definitive diagnosis and initial evaluation of the horseshoe kidney anatomy, as well as identification of any obstructions or calculi.

Judicious use of diuretic renal scans and voiding cystourethrograms helps identify ureteropelvic junction obstructions and vesicoureteral reflux that may not be clear from the CT scans alone. 24-hour urine testing and prophylactic therapy for patients with horseshoe kidneys who develop urinary calculi is recommended. Percutaneous, ureteroscopic, laparoscopic, and robotic surgery can now be safely performed on horseshoe kidneys, but may be technically challenging and require additional planning.

Horseshoe kidneys are the most common congenital renal fusion defect, but they affect only about 0.25% of the population. Many professionals are unaware of the condition, its evaluation, recommended monitoring, or treatment. Due to its rarity, optimal management of horseshoe kidneys requires a coordinated, multidisciplinary approach to improve team performance, safety, outcomes, and patient care.

Clinicians must provide an early, accurate diagnosis, risk stratification, and individualized surveillance plans, recognizing the increased risk of complications, such as obstruction, nephrolithiasis, infection, and chronic kidney disease. Advanced practitioners and nurses play a critical role in patient education, early identification of complications, and reinforcement of adherence to follow-up and lifestyle modifications, such as hydration and infection prevention.[1][14][57]

Pharmacists are essential for medication reconciliation, optimizing antibiotic stewardship in UTIs, and counseling on nephrotoxic drug avoidance. Given the unique vascular and anatomic considerations in horseshoe kidneys, radiologists and urologists must collaborate closely to interpret complex imaging and plan interventions.[1][122] Surgeons must be skilled in minimally invasive and open techniques, with preoperative planning that accounts for aberrant vasculature and renal anatomy to minimize intraoperative risk.[1][81]

Effective interprofessional communication is necessary for timely information sharing, especially regarding imaging findings, laboratory results, and perioperative planning. Regular multidisciplinary case reviews and care conferences can facilitate consensus on management strategies for complex cases.[122] Ethical considerations include respecting patient autonomy, providing clear information about risks and benefits of surveillance versus intervention, and ensuring equitable access to specialized care.

Care coordination is vital, particularly for pediatric patients or those with associated anomalies, to ensure seamless transitions between specialties and continuity of care.[57] The healthcare team must maintain up-to-date knowledge of evolving management strategies and foster a culture of safety, vigilance, and shared decision-making to optimize outcomes for patients with horseshoe kidneys.

Media

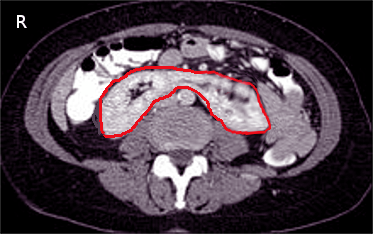

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Horseshoe Kidney on Computed Tomography. This axial computed tomography image shows a horseshoe kidney, a congenital anomaly where the lower poles of both kidneys are fused, forming a U-shaped structure. The red outline highlights the fused renal tissue crossing the midline anterior to the vertebral column.

Contributed by S Bhimji, MD

References

Humphries A, Speroni S, Eden K, Nolan M, Gilbert C, McNamara J. Horseshoe kidney: Morphologic features, embryologic and genetic etiologies, and surgical implications. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2023 Nov:36(8):1081-1088. doi: 10.1002/ca.24018. Epub 2023 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 36708162]

Natsis K, Piagkou M, Skotsimara A, Protogerou V, Tsitouridis I, Skandalakis P. Horseshoe kidney: a review of anatomy and pathology. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2014 Aug:36(6):517-26. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1229-7. Epub 2013 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 24178305]

Hohenfellner M, Schultz-Lampel D, Lampel A, Steinbach F, Cramer BM, Thüroff JW. Tumor in the horseshoe kidney: clinical implications and review of embryogenesis. The Journal of urology. 1992 Apr:147(4):1098-102 [PubMed PMID: 1552596]

Eisendrath DN, Phifer FM, Culver HB. HORSESHOE KIDNEY. Annals of surgery. 1925 Nov:82(5):735-64 [PubMed PMID: 17865363]

Crawford ES, Coselli JS, Safi HJ, Martin TD, Pool JL. The impact of renal fusion and ectopia on aortic surgery. Journal of vascular surgery. 1988 Oct:8(4):375-83 [PubMed PMID: 3172375]

Glodny B, Petersen J, Hofmann KJ, Schenk C, Herwig R, Trieb T, Koppelstaetter C, Steingruber I, Rehder P. Kidney fusion anomalies revisited: clinical and radiological analysis of 209 cases of crossed fused ectopia and horseshoe kidney. BJU international. 2009 Jan:103(2):224-35. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07912.x. Epub 2008 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 18710445]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStroosma OB, Scheltinga MR, Stubenitsky BM, Kootstra G. Horseshoe kidney transplantation: an overview. Clinical transplantation. 2000 Dec:14(6):515-9 [PubMed PMID: 11127302]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhougali HS, Alawad OAMA, Farkas N, Ahmed MMM, Abuagla AM. Bilateral pelvic kidneys with upper pole fusion and malrotation: a case report and review of the literature. Journal of medical case reports. 2021 Apr 5:15(1):181. doi: 10.1186/s13256-021-02761-1. Epub 2021 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 33814014]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGLENN JF. Analysis of 51 patients with horseshoe kidney. The New England journal of medicine. 1959 Oct 1:261():684-7 [PubMed PMID: 13828436]

O'Hara PJ, Hakaim AG, Hertzer NR, Krajewski LP, Cox GS, Beven EG. Surgical management of aortic aneurysm and coexistent horseshoe kidney: review of a 31-year experience. Journal of vascular surgery. 1993 May:17(5):940-7 [PubMed PMID: 8487363]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlamer A. Renal cell carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney: radiology and pathology correlation. Journal of clinical imaging science. 2013:3():12. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.109725. Epub 2013 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 23814684]

Ying-Long S, Yue-Min X, Hong X, Xiao-Lin X. Papillary renal cell carcinoma in the horseshoe kidney. Southern medical journal. 2010 Dec:103(12):1272-4. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181f9670a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21037511]

Schiappacasse G, Aguirre J, Soffia P, Silva CS, Zilleruelo N. CT findings of the main pathological conditions associated with horseshoe kidneys. The British journal of radiology. 2015 Jan:88(1045):20140456. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140456. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25375751]

Kang M, Kim YC, Lee H, Kim DK, Oh KH, Joo KW, Kim YS, Chin HJ, Han SS. Renal outcomes in adult patients with horseshoe kidney. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2021 Feb 20:36(3):498-503. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfz217. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31697372]

Chopra P, St-Vil D, Yazbeck S. Blunt renal trauma-blessing in disguise? Journal of pediatric surgery. 2002 May:37(5):779-82 [PubMed PMID: 11987100]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKrutsri C, Singhatas P, Sumpritpradit P, Chaijareenont C, Viseshsindh W, Thampongsa T, Choikrua P. Traumatic Blunt Force Renal Injury in a Diseased Horseshoe Kidney with Successful Embolization to Treat Active Bleeding: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case reports in urology. 2020:2020():8897208. doi: 10.1155/2020/8897208. Epub 2020 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 32774982]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMurphy JT, Borman KR, Dawidson I. Renal autotransplantation after horseshoe kidney injury: a case report and literature review. The Journal of trauma. 1996 May:40(5):840-4 [PubMed PMID: 8614094]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShah HU, Ojili V. Multimodality imaging spectrum of complications of horseshoe kidney. The Indian journal of radiology & imaging. 2017 Apr-Jun:27(2):133-140. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_298_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28744072]

Je BK, Kim HK, Horn PS. Incidence and Spectrum of Renal Complications and Extrarenal Diseases and Syndromes in 380 Children and Young Adults With Horseshoe Kidney. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2015 Dec:205(6):1306-14. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14625. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26587938]

Doménech-Mateu JM, Gonzalez-Compta X. Horseshoe kidney: a new theory on its embryogenesis based on the study of a 16-mm human embryo. The Anatomical record. 1988 Dec:222(4):408-17 [PubMed PMID: 3228209]

Soriano RM, Penfold D, Leslie SW. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Kidneys. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494007]

Muttarak M, Sriburi T. Congenital renal anomalies detected in adulthood. Biomedical imaging and intervention journal. 2012 Jan:8(1):e7. doi: 10.2349/biij.8.1.e7. Epub 2012 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 22970063]

Rehman S, Ahmed D. Embryology, Kidney, Bladder, and Ureter. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31613527]

Donovan MF, Cascella M. Embryology, Weeks 6-8. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33085328]

Lallas CD, Pak RW, Pagnani C, Hubosky SG, Yanke BV, Keeley FX, Bagley DH. The minimally invasive management of ureteropelvic junction obstruction in horseshoe kidneys. World journal of urology. 2011 Feb:29(1):91-5. doi: 10.1007/s00345-010-0523-9. Epub 2010 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 20204377]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTaghavi K, Kirkpatrick J, Mirjalili SA. The horseshoe kidney: Surgical anatomy and embryology. Journal of pediatric urology. 2016 Oct:12(5):275-280. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.04.033. Epub 2016 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 27324557]

Pascual Samaniego M, Bravo Fernández I, Ruiz Serrano M, Ramos Martín JA, Lázaro Méndez J, García González A. [Traumatic rupture of a horseshoe kidney]. Actas urologicas espanolas. 2006 Apr:30(4):424-8 [PubMed PMID: 16838618]

Solhaug MJ, Bolger PM, Jose PA. The developing kidney and environmental toxins. Pediatrics. 2004 Apr:113(4 Suppl):1084-91 [PubMed PMID: 15060203]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFriedland GW, de Vries P. Renal ectopia and fusion. Embryologic Basis. Urology. 1975 May:5(5):698-706 [PubMed PMID: 1129903]

Mandell GA, Maloney K, Sherman NH, Filmer B. The renal axes in spina bifida: issues of confusion and fusion. Abdominal imaging. 1996 Nov-Dec:21(6):541-5 [PubMed PMID: 8875880]

Majos M, Polguj M, Szemraj-Rogucka Z, Arazińska A, Stefańczyk L. The level of origin of renal arteries in horseshoe kidney vs. in separated kidneys: CT-based study. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2018 Oct:40(10):1185-1191. doi: 10.1007/s00276-018-2071-8. Epub 2018 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 30043151]

Tripathi P, Guo Q, Wang Y, Coussens M, Liapis H, Jain S, Kuehn MR, Capecchi MR, Chen F. Midline signaling regulates kidney positioning but not nephrogenesis through Shh. Developmental biology. 2010 Apr 15:340(2):518-27. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.02.007. Epub 2010 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 20152829]

Schumacher V, Thumfart J, Drechsler M, Essayie M, Royer-Pokora B, Querfeld U, Müller D. A novel WT1 missense mutation presenting with Denys-Drash syndrome and cortical atrophy. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2006 Feb:21(2):518-21 [PubMed PMID: 16303781]

Cereda A, Carey JC. The trisomy 18 syndrome. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2012 Oct 23:7():81. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-81. Epub 2012 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 23088440]

Ranke MB, Saenger P. Turner's syndrome. Lancet (London, England). 2001 Jul 28:358(9278):309-14 [PubMed PMID: 11498234]

Harris J, Robert E, Källén B. Epidemiologic characteristics of kidney malformations. European journal of epidemiology. 2000:16(11):985-92 [PubMed PMID: 11421481]

Benidir T, Coelho de Castilho TJ, Cherubini GR, de Almeida Luz M. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l'Association des urologues du Canada. 2014 Nov:8(11-12):E918-20. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.2289. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25553168]

Bhattarai B, Kulkarni AH, Rao ST, Mairpadi A. Anesthetic consideration in downs syndrome--a review. Nepal Medical College journal : NMCJ. 2008 Sep:10(3):199-203 [PubMed PMID: 19253867]

Araki K, Matsumoto K, Shiraishi T, Ogura H, Kurashige T, Kitamura I. Turner's syndrome with agenesis of the corpus callosum, Hashimoto's thyroiditis and horseshoe kidney. Acta paediatrica Japonica : Overseas edition. 1987 Aug:29(4):622-6 [PubMed PMID: 3144902]

Sagi-Dain L, Maya I, Falik-Zaccai T, Feingold-Zadok M, Lev D, Yonath H, Kaliner E, Frumkin A, Ben Shachar S, Singer A. Isolated fetal horseshoe kidney does not seem to increase the risk for abnormal chromosomal microarray results. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2018 Mar:222():80-83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.01.015. Epub 2018 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 29367169]

Marrak M, Chaker K, Ouanes Y, Azouz E, Mosbahi B, Nouira Y. Traumatic renal injury revealing a horseshoe kidney: A case report. Urology case reports. 2023 Mar:47():102357. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2023.102357. Epub 2023 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 36860417]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMolina Escudero R, Cancho Gil MJ, Husillos Alonso A, Lledó García E, Herranz Amo F, Ogaya Piniés G, Ramón Botella E, Simó G, Navas Martínez MC, Hernández Fernández C. Traumatic rupture of horseshoe kidney. Urologia internationalis. 2012:88(1):112-4. doi: 10.1159/000330800. Epub 2011 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 21934278]

Bhandarkar KP, Kittur DH, Patil SV, Jadhav SS. Horseshoe kidney and associated anomalies: Single institutional review of 20 cases. African journal of paediatric surgery : AJPS. 2018 Apr-Jun:15(2):104-107. doi: 10.4103/ajps.AJPS_55_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31290474]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHeinonen PK. Distribution of female genital tract anomalies in two classifications. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2016 Nov:206():141-146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.09.009. Epub 2016 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 27693935]

Pawar AS, Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Sakhuja A, Mao MA, Erickson SB. Incidence and characteristics of kidney stones in patients with horseshoe kidney: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Urology annals. 2018 Jan-Mar:10(1):87-93. doi: 10.4103/UA.UA_76_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29416282]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLeslie SW, Bashir K. Hypocitraturia and Renal Calculi. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33232062]

Leslie SW, Sajjad H. Hypercalciuria. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846247]

Agarwal S, Yadav RN, Kumar M, Sankhwar S. Horseshoe kidney with unilateral single ectopic ureter. BMJ case reports. 2018 Jun 11:2018():. pii: bcr-2017-223913. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-223913. Epub 2018 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 29895545]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceElmaadawy MIA, Kim SW, Kang SK, Han SW, Lee YS. A retrospective analysis of ureteropelvic junction obstructions in patients with horseshoe kidney. Translational andrology and urology. 2021 Nov:10(11):4173-4180. doi: 10.21037/tau-21-471. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34984183]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceShadpour P, Akhyari HH, Maghsoudi R, Etemadian M. Management of ureteropelvic junction obstruction in horseshoe kidneys by an assortment of laparoscopic options. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l'Association des urologues du Canada. 2015 Nov-Dec:9(11-12):E775-9. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3111. Epub 2015 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 26600883]

Lotfollahzadeh S, Leslie SW, Aeddula NR. Vesicoureteral Reflux. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33085409]

O'Brien J, Buckley O, Doody O, Ward E, Persaud T, Torreggiani W. Imaging of horseshoe kidneys and their complications. Journal of medical imaging and radiation oncology. 2008 Jun:52(3):216-26. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2008.01950.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18477115]

Lee CT, Hilton S, Russo P. Renal mass within a horseshoe kidney: preoperative evaluation with three-dimensional helical computed tomography. Urology. 2001 Jan:57(1):168 [PubMed PMID: 11164171]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBanker H, Sheffield EG, Cohen HL. Nuclear Renal Scan. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32965907]

Al Aaraj MS, Badreldin AM. Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809575]

Kim H, Lee SJ, Kim W. A Case of Horseshoe Kidney and Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease with PKD1 Gene Mutation. Journal of clinical medicine. 2025 Jun 5:14(11):. doi: 10.3390/jcm14114008. Epub 2025 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 40507770]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYavuz S, Kıyak A, Sander S. Renal outcome of children with horseshoe kidney: a single-center experience. Urology. 2015 Feb:85(2):463-6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.10.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25623720]

Pitts WR Jr, Muecke EC. Horseshoe kidneys: a 40-year experience. The Journal of urology. 1975 Jun:113(6):743-6 [PubMed PMID: 1152146]

Cascio S, Sweeney B, Granata C, Piaggio G, Jasonni V, Puri P. Vesicoureteral reflux and ureteropelvic junction obstruction in children with horseshoe kidney: treatment and outcome. The Journal of urology. 2002 Jun:167(6):2566-8 [PubMed PMID: 11992090]

Lampel A, Hohenfellner M, Schultz-Lampel D, Lazica M, Bohnen K, Thürof JW. Urolithiasis in horseshoe kidneys: therapeutic management. Urology. 1996 Feb:47(2):182-6 [PubMed PMID: 8607230]

Thakore P, Liang TH. Urolithiasis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644527]

Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Murphy PB. Renal Calculi, Nephrolithiasis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28723043]

Wason SE, Leslie SW. Ureteroscopy. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809391]

Manzoor H, Leslie SW, Saikali SW. Extracorporeal Shockwave Lithotripsy. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809722]

Cormio A, Mantovan M, Palantrani V, Beltrami M, Fuligni D, Passarella V, Cammarata V, Brocca C, Somani BK, Gauhar V, Carrieri G, Cormio L, Galosi AB, Castellani D. A narrative review on extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, ureterolithotripsy, and percutaneous nephrolithotripsy in patients with anomalous kidneys. Minerva urology and nephrology. 2025 Feb:77(1):43-51. doi: 10.23736/S2724-6051.25.06001-X. Epub [PubMed PMID: 40183182]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStein RJ, Desai MM. Management of urolithiasis in the congenitally abnormal kidney (horseshoe and ectopic). Current opinion in urology. 2007 Mar:17(2):125-31 [PubMed PMID: 17285023]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRais-Bahrami S, Friedlander JI, Duty BD, Okeke Z, Smith AD. Difficulties with access in percutaneous renal surgery. Therapeutic advances in urology. 2011 Apr:3(2):59-68. doi: 10.1177/1756287211400661. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21869906]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSadiq AS, Atallah W, Khusid J, Gupta M. The Surgical Technique of Mini Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy. Journal of endourology. 2021 Sep:35(S2):S68-S74. doi: 10.1089/end.2020.1080. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34499550]

Pearle MS, Goldfarb DS, Assimos DG, Curhan G, Denu-Ciocca CJ, Matlaga BR, Monga M, Penniston KL, Preminger GM, Turk TM, White JR, American Urological Assocation. Medical management of kidney stones: AUA guideline. The Journal of urology. 2014 Aug:192(2):316-24. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.05.006. Epub 2014 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 24857648]

Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Bashir K. 24-Hour Urine Testing for Nephrolithiasis: Interpretation and Treatment Guidelines. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494055]

Türk C, Petřík A, Sarica K, Seitz C, Skolarikos A, Straub M, Knoll T. EAU Guidelines on Diagnosis and Conservative Management of Urolithiasis. European urology. 2016 Mar:69(3):468-74. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.040. Epub 2015 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 26318710]

Dion M, Ankawi G, Chew B, Paterson R, Sultan N, Hoddinott P, Razvi H. CUA guideline on the evaluation and medical management of the kidney stone patient - 2016 update. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l'Association des urologues du Canada. 2016 Nov-Dec:10(11-12):E347-E358. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4218. Epub 2016 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 28096919]

Ennis JL, Asplin JR. The role of the 24-h urine collection in the management of nephrolithiasis. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2016 Dec:36(Pt D):633-637. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.11.020. Epub 2016 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 27840312]

Williams JC Jr, Gambaro G, Rodgers A, Asplin J, Bonny O, Costa-Bauzá A, Ferraro PM, Fogazzi G, Fuster DG, Goldfarb DS, Grases F, Heilberg IP, Kok D, Letavernier E, Lippi G, Marangella M, Nouvenne A, Petrarulo M, Siener R, Tiselius HG, Traxer O, Trinchieri A, Croppi E, Robertson WG. Urine and stone analysis for the investigation of the renal stone former: a consensus conference. Urolithiasis. 2021 Feb:49(1):1-16. doi: 10.1007/s00240-020-01217-3. Epub 2020 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 33048172]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRamkumar H, Ahmed SM, Syed E, Tuazon J. Horseshoe kidney in an 80 year old with chronic kidney disease. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2009 Dec 16:9():1346-7. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2009.165. Epub 2009 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 20024508]

Campi R, Sessa F, Rivetti A, Pecoraro A, Barzaghi P, Morselli S, Polverino P, Nicoletti R, Li Marzi V, Spatafora P, Sebastianelli A, Gacci M, Vignolini G, Serni S. Case Report: Optimizing Pre- and Intraoperative Planning With Hyperaccuracy Three-Dimensional Virtual Models for a Challenging Case of Robotic Partial Nephrectomy for Two Complex Renal Masses in a Horseshoe Kidney. Frontiers in surgery. 2021:8():665328. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.665328. Epub 2021 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 34136528]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSobrinho ULGP, Albero JRP, Becalli MLP, Sampaio FJB, Favorito LA. Three-dimensional printing models of horseshoe kidney and duplicated pelvicalyceal collecting system for flexible ureteroscopy training: a pilot study. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2021 Jul-Aug:47(4):887-889. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2021.99.10. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33848082]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu Y, Song H, Wang B, Xiao B, Hu W, Xu Y, Su B, Li X, Li J. Application of Mixed Reality Technology in the Planning of PCNL for Special Types of Complex Upper Urinary Stones: A Pilot Study. Urology. 2025 Feb:196():40-47. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2024.09.024. Epub 2024 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 39481810]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMercader C, Vilaseca A, Moreno JL, López A, Sebastià MC, Nicolau C, Ribal MJ, Peri L, Costa M, Alcaraz A. Role of the three-dimensional printing technology incomplex laparoscopic renal surgery: a renal tumor in a horseshoe kidney. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2019 Nov-Dec:45(6):1129-1135. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2019.0085. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31808400]

Garcia-Segui A, Ferrández-Jimenez M, García-Cárceles N, Soler-López C. Laparoscopic heminephroureterectomy of horseshoe kidney with suspected urothelial carcinoma using a hyper accuracy 3D virtual model. Actas urologicas espanolas. 2025 Mar 17:():501747. doi: 10.1016/j.acuroe.2025.501747. Epub 2025 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 40107611]

Yohannes P, Smith AD. The endourological management of complications associated with horseshoe kidney. The Journal of urology. 2002 Jul:168(1):5-8 [PubMed PMID: 12050480]

Yang QT, Hong YX, Hou GM, Zheng JH, Sui XX. Retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy for a horseshoe kidney with hydronephrosis and inflammation: A case report. Medicine. 2019 May:98(22):e15697. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015697. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31145283]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl Muzrakchi A, Aker LJA, Barah A, Alsherbini A, Omar A. Alternating Biplanar Fluoroscopy in Percutaneous Nephrostomy to Approach Stones in Patients With Horseshoe Kidney: An Institutional Experience. Cureus. 2021 Jul:13(7):e16542. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16542. Epub 2021 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 34430150]

Quintana Álvarez R, Herranz Amo F, Bueno Chomón G, Subirá Ríos D, Bataller Monfort V, Hernández Cavieres J, Hernández Fernández C. Surgical management of horseshoe kidney tumors. Literature review and analysis of two cases. Actas urologicas espanolas. 2021 Sep:45(7):493-497. doi: 10.1016/j.acuroe.2021.06.005. Epub 2021 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 34326031]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceXiong M, Chen Z, Wang X, Jiang H, Luo Z, Liang G, Hou T. Intraperitoneal laparoscopic technique in trendelenburg position: an effective surgical method for pyelolithotomy, pyeloplasty, and heminephrectomy in patients with horseshoe kidneys. BMC urology. 2024 Oct 28:24(1):236. doi: 10.1186/s12894-024-01631-4. Epub 2024 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 39468533]

Esposito C, Masieri L, Blanc T, Manzoni G, Silay S, Escolino M. Robot-assisted laparoscopic pyeloplasty (RALP) in children with horseshoe kidneys: results of a multicentric study. World journal of urology. 2019 Oct:37(10):2257-2263. doi: 10.1007/s00345-019-02632-x. Epub 2019 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 30643972]

Li Z, Li X, Fan S, Yang K, Meng C, Xiong S, Chen S, Li Z, Li X. Robot-assisted modified bilateral dismembered V-shaped flap pyeloplasty for ureteropelvic junction obstruction in horseshoe kidney using KangDuo-Surgical-Robot-01 system. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2023 May-Jun:49(3):388-390. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2022.0525. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36515621]

Chammas M Jr, Feuillu B, Coissard A, Hubert J. Laparoscopic robotic-assisted management of pelvi-ureteric junction obstruction in patients with horseshoe kidneys: technique and 1-year follow-up. BJU international. 2006 Mar:97(3):579-83 [PubMed PMID: 16469030]

Myint M, Luke S, Louie-Johnsun M. Laparoscopic pyelolithotomy and pyeloplasty in a horseshoe kidney. ANZ journal of surgery. 2015 Jun:85(6):492-3. doi: 10.1111/ans.12458. Epub 2013 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 24251980]

An LY, Zhang H, Xiong M, Luo CG, Xu B, Li K, Wang C, Xu YZ, Tian Y, Luo GH, Ban Y. [Application of robot-assisted laparoscopic isthmectomy for the treatment of symptomatic horseshoe kidney]. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 2024 Dec 24:104(48):4427-4430. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20240924-02174. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39690540]

Shiomi E, Goto Y, Ito A, Ikarashi D, Maekawa S, Kato R, Kanehira M, Sugimura J, Obara W. A Case of Right Renal Cell Carcinoma in a Horseshoe Kidney Resected Using Robot-Assisted Radical Nephrectomy. Asian journal of endoscopic surgery. 2025 Jan-Dec:18(1):e70111. doi: 10.1111/ases.70111. Epub [PubMed PMID: 40592576]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShiode R, Watanabe R, Kakuda T, Suzuki D, Nobumori S, Sugihara N, Yamakawa M, Saiki K, Kono R, Noda T, Nishimura K, Fukumoto T, Miura N, Miyauchi Y, Kikugawa T, Saika T. Robot-Assisted Radical Nephroureterectomy in a Patient With Horseshoe Kidney: A Case Report. Asian journal of endoscopic surgery. 2025 Jan-Dec:18(1):e70054. doi: 10.1111/ases.70054. Epub [PubMed PMID: 40210236]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKobari Y, Yoshida K, Endo T, Minoda R, Fukuda H, Mizoguchi S, Iizuka J, Ishida H, Takagi T. Robot-assisted Partial Nephrectomy With Selective Artery Clamping for Renal Cell Carcinoma in Horseshoe Kidney. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2024 Jul-Aug:38(4):2085-2089. doi: 10.21873/invivo.13668. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38936940]

Shoji R, Teraishi F, Matsumi Y, Kashima H, Fujiwara T. Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer in a patient with a horseshoe kidney: A case report. Asian journal of endoscopic surgery. 2024 Apr:17(2):e13296. doi: 10.1111/ases.13296. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38414217]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLatif ER, Ahmed I, Thomas M, Eddy B. Robotic nephroureterectomy in a horseshoe kidney for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. BMJ case reports. 2021 Jun 9:14(6):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-234901. Epub 2021 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 34108151]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRaman A, Kuusk T, Hyde ER, Berger LU, Bex A, Mumtaz F. Robotic-assisted Laparoscopic Partial Nephrectomy in a Horseshoe Kidney. A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Urology. 2018 Apr:114():e3-e5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.12.003. Epub 2017 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 29288785]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAgrawal S, Kalathia J, Chipde SS, Mishra U, Tyagi A, Parashar S. Laparoscopic heminephrectomy in horseshoe kidneys: A single center experience. Urology annals. 2017 Oct-Dec:9(4):357-361. doi: 10.4103/UA.UA_114_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29118539]

Kubihal V, Razik A, Sharma S, Das CJ. Unveiling the confusion in renal fusion anomalies: role of imaging. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2021 Sep:46(9):4254-4265. doi: 10.1007/s00261-021-03072-1. Epub 2021 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 33811515]

Aquilina J, Neves JB, Berger L, Mumtaz F, Banga N, Tran MG. Complex Open Pyeloplasty in a Pelvic Kidney. Urology. 2020 Jul:141():e47-e48. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.03.048. Epub 2020 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 32305554]

Mahboob M, Rout P, Leslie SW, Bokhari SRA. Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422529]

Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Harris PC, Torres VE. Polycystic Kidney Disease, Autosomal Dominant. GeneReviews(®). 1993:(): [PubMed PMID: 20301424]

Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Murphy PB. Wilms Tumor. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28723033]

Balis F, Green DM, Anderson C, Cook S, Dhillon J, Gow K, Hiniker S, Jasty-Rao R, Lin C, Lovvorn H, MacEwan I, Martinez-Agosto J, Mullen E, Murphy ES, Ranalli M, Rhee D, Rokitka D, Tracy EL, Vern-Gross T, Walsh MF, Walz A, Wickiser J, Zapala M, Berardi RA, Hughes M. Wilms Tumor (Nephroblastoma), Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2021 Aug 1:19(8):945-977. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0037. Epub 2021 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 34416707]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCook WA, Stephens FD. Fused kidneys: morphologic study and theory of embryogenesis. Birth defects original article series. 1977:13(5):327-40 [PubMed PMID: 588702]

Neville H, Ritchey ML, Shamberger RC, Haase G, Perlman S, Yoshioka T. The occurrence of Wilms tumor in horseshoe kidneys: a report from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group (NWTSG). Journal of pediatric surgery. 2002 Aug:37(8):1134-7 [PubMed PMID: 12149688]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRubio Briones J, Regalado Pareja R, Sánchez Martín F, Chéchile Toniolo G, Huguet Pérez J, Villavicencio Mavrich H. Incidence of tumoural pathology in horseshoe kidneys. European urology. 1998:33(2):175-9 [PubMed PMID: 9519360]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHuang EY, Mascarenhas L, Mahour GH. Wilms' tumor and horseshoe kidneys: a case report and review of the literature. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2004 Feb:39(2):207-12 [PubMed PMID: 14966742]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKölln CP, Boatman DL, Schmidt JD, Flocks RH. Horseshoe kidney: a review of 105 patients. The Journal of urology. 1972 Feb:107(2):203-4 [PubMed PMID: 5061443]

Luu DT, Duc NM, Tra My TT, Bang LV, Lien Bang MT, Van ND. Wilms' Tumor in Horseshoe Kidney. Case reports in nephrology and dialysis. 2021 May-Aug:11(2):124-128. doi: 10.1159/000514774. Epub 2021 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 34250029]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTkocz M, Kupajski M. Tumour in horseshoe kidney - different surgical treatment shown in five example cases. Contemporary oncology (Poznan, Poland). 2012:16(3):254-7. doi: 10.5114/wo.2012.29295. Epub 2012 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 23788890]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMano R, Hakimi AA, Sankin AI, Sternberg IA, Chevinsky MS, Russo P. Surgical Treatment of Tumors Involving Kidneys With Fusion Anomalies: A Contemporary Series. Urology. 2016 Dec:98():97-102. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.07.034. Epub 2016 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 27498249]

Iovino F, Mongardini FM, Balestrucci G, Regginelli A, Ronchi A, Ferrara MG, Parisi S, Gambardella C, Lucido FS, Tolone S, Ruggiero R, Docimo L. Large renal lymphoma in a patient with horseshoe kidney: A case report. Oncology letters. 2024 Feb:27(2):46. doi: 10.3892/ol.2023.14180. Epub 2023 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 38115986]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShi SS, Yang XZ, Zhang XY, Guo HD, Wang WF, Zhang L, Wu P, Zhang W, Wen WB, Huo XL, Zhang YQ. Horseshoe kidney with PLA2R-positive membranous nephropathy. BMC nephrology. 2021 Aug 10:22(1):277. doi: 10.1186/s12882-021-02488-7. Epub 2021 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 34376183]

Boatman DL, Kölln CP, Flocks RH. Congenital anomalies associated with horseshoe kidney. The Journal of urology. 1972 Feb:107(2):205-7 [PubMed PMID: 5061444]

Kumata H, Takayama T, Asami K, Haga I. Living-Donor Kidney Transplantation With Laparoscopic Nephrectomy From a Donor With Horseshoe Kidney: A Case Report. Transplantation proceedings. 2021 May:53(4):1257-1261. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2021.03.015. Epub 2021 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 33892929]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDe Pablos-Rodríguez P, Suárez JF, Riera Canals L, Sanz-Serra P, Vigués F. Horseshoe kidney splitting technique for transplantation. Urology case reports. 2021 Jul:37():101604. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2021.101604. Epub 2021 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 33665125]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaryła M, Dymkowski M, Pliszczynski J. Vascular Challenges in Horseshoe Kidney Transplantation: A Case Report. Annals of transplantation. 2025 Jul 15:30():e949896. doi: 10.12659/AOT.949896. Epub 2025 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 40660664]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePerin L, Romano M, Bona ED, Finotti M, Iacomino A, Mangino M, Sergi F, Maffei R, Nordio M, Zanatta P, Zanus G. Horseshoe Kidney Transplantation from a Deceased Cardiac Death Donor: A Case Report. Transplantation proceedings. 2025 Sep:57(7):1233-1237. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2025.05.010. Epub 2025 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 40541506]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVijay A, Ghasemian SR. Case Report: Horseshoe Kidney Transplantation Using Split Technique. Transplantation proceedings. 2022 Oct:54(8):2179-2181. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2022.08.023. Epub 2022 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 36175175]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSengupta B, Khan I, Saiaghi A, Gaw EA, Tawfeeq M, AlQahtani MS, Obeid M. En Bloc Transplantation of Horseshoe Kidney from Deceased Donor: An Unusual Transplantation Utilizing Kidneys with Congenital Fusion Abnormality. Case reports in transplantation. 2021:2021():2286831. doi: 10.1155/2021/2286831. Epub 2021 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 34422430]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYasuda Y, Zhang JJ, Attawettayanon W, Rathi N, Roversi G, Zhang A, Palacios DA, Kaouk J, Haber GP, Krishnamurthi V, Eltemamy M, Abouassaly R, Martin CE, Weight C, Campbell SC. Pathologic Findings and Management of Renal Mass in Horseshoe Kidneys. Urology. 2022 Aug:166():170-176. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2022.03.020. Epub 2022 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 35405205]