Introduction

Glomangiomas, or glomuvenous malformations (GVM), are rare cutaneous venous malformations that show glomus cells (undifferentiated smooth muscle cells, which are thermoregulatory units), along with the venous system in histology.[1] Glomus cells are specialized smooth muscle cells that regulate the temperature in the body.[2] Masson first described glomangiomas, and Papoff further extensively studied them.[3] There are 3 types of glomus tumors, classified based on their dominant component:

- Solid: mainly glomus cells

- Glomangioma: mainly blood vessels.

- Glomangiomyoma: mainly smooth muscle cells [4]

- Glomangiomas are further divided into regional, disseminated, and congenital plaque-like.[5]

Glomangiomas usually present in multiples, often at birth or during childhood, and they do not involve the subungual region. A majority of glomangiomas are benign, although malignant cases have also been reported.[6][7] Rarely seen, the disseminated type distributes throughout the body.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Glomus tumors, particularly glomangiomas, can arise through inherited or sporadic pathways. Understanding the underlying genetic mechanisms is essential for accurate diagnosis, counseling, and management.

Inherited or Familial Glomangiomas (38%–68%) The familial form of glomangiomas typically follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance and variable expression. The responsible gene, glomulin, is located on chromosome 1p21-22, within a 4 cm to 6 cm region mapped using YAC and PAC libraries. To date, 14 distinct loss-of-function mutations in the glomulin gene have been identified in affected individuals, which lead to elevated levels of cyclin E and c-Myc, contributing to cellular dysregulation.[8][7][9][10] Approximately 60% of familial cases involve at least 1 additional affected family member. Clinical onset may occur at birth or emerge during adolescence. Another identified mutation, 157_161del, has been documented as contributing to GVMs.[11] A notable subtype, segmental type 2 glomangiomas, begins with a solitary primary lesion, followed by the development of multiple distal lesions. This pattern is considered a manifestation of mosaicism within the inherited form.

Sporadic or De Novo Mutations Sporadic glomangiomas, which are not associated with a family history, can also present at birth and arise from spontaneous genetic mutations.[12]

Epidemiology

Glomangiomas are responsible for 1.6% to 2.0% of soft skin tumors and 20% of all glomus tumors. Plaque-like glomangiomas are very rare, with only 4 cases reported so far. It is more predominant in the male gender. About one-third of the patients present before the age of 20.[8][13][14] 10% of cases are of the disseminated type.[10] The most common reason for referral among vascular anomalies is venous malformations.[15]

Histopathology

These lesions are distinguishable by glomus cells surrounded by enlarged, dilated vein-like tubes. Glomus cells are poorly differentiated smooth muscle cells. They stain positive for vimentin, calponin, and SMC alpha-actin. They are negative for S-100, von Willebrand factor, and desmin.[1][7]

History and Physical

Glomus cancers, particularly glomangiomas, typically present at birth as bluish-purple skin lesions arranged in a cobblestone-like pattern. These lesions are often papular or nodular, hyperkeratotic, and range from 2 mm to 10 mm in diameter, though their size and number can vary significantly. Tenderness on palpation is common, with pain frequently triggered by pressure or exposure to cold stimuli.[1][12] Lesions predominantly occur in areas rich in glomus bodies, especially the distal extremities such as the palms, wrists, forearms, feet, and subungual regions. Approximately 75% of cases involve the hands.[8]

Visceral involvement is extremely rare but has been reported in sites including the nasal cavity, mediastinum, gastrointestinal tract, respiratory and urogenital tracts, and hepatobiliary system. Additionally, some patients with GVMs have presented with congenital cardiac anomalies such as ventricular septal defects and transposition of the great vessels.[6][16][17] Though glomus bodies are absent in normal nerve tissue, there is a case report describing nerve involvement by glomangioma.[18] Tracheal lesions, though rare, may cause dyspnea, hemoptysis, and retrosternal chest pain.[19]

Compared to solitary glomus tumors, glomangiomas tend to be larger, less well-circumscribed, and demonstrate slower blood flow. These lesions generally grow gradually over time. While the classic clinical triad—hypersensitivity, intermittent pain, and pinpoint pain—is considered characteristic of glomus tumors, it is rarely observed in glomangiomas.[20] A rare variant, the plaque-like type, presents as indurated, nodular, or discolored lesions that are typically non-tender but may bleed easily with minor trauma. These lesions are usually larger than other glomangioma types and represent the rarest clinical presentation.[14]

Evaluation

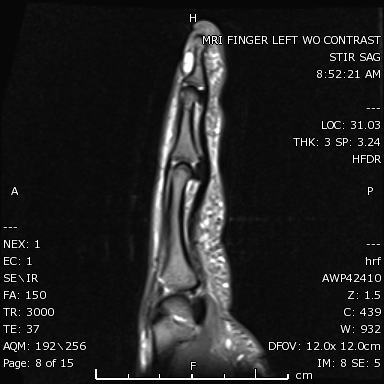

The confirmation of the diagnosis is through histopathology.[8] If a tumor has atypical histology, immunohistochemistry assists in diagnosis. The role of smoothelin should be considered, as it is an indicator of the smooth muscle cell.[20] Electron microscopy shows glomus cells with dense bodies and smooth muscle myofibrils [1]. An X-ray may show osseous defects. Magnetic resonance imaging and color Doppler ultrasonography help define shape, size, and accurate location (see Image).[21][13] Dynamic time-resolved contrast-enhanced MR angiography can define vascularity.[22]

Treatment / Management

The goal of treatment is to decrease the symptoms. For asymptomatic lesions, monitoring and observation are recommended. Surgery, electron-beam radiation, sclerotherapy with hypertonic saline or sodium tetradecyl sulfate, argon, flash lamp tunable dye laser (for multiple lesions), and CO2 lasers are different treatment modalities.[8][7] Excision therapy is the preferred treatment for painful lesions. Sclerotherapy was shown to be more effective in venous malformation than GVMs. In cases of nasal involvement, endoscopic excision or surgery is recommended.[9][23][24] In cases of large glomangiomas that are difficult to excise, the 1064-nm Nd: YAG laser is effective.[25] Also, positive results with the Nd: YAG laser have been reported in symptomatic familial cases.[26][27] External compression by elastic compressive garments worsens the pain.[12](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis for glomus cancers includes:

- Venous malformations: Glomangiomas are limited to the skin and mucosa. In contrast, other types of venous malformations can extend to deeper layers like muscles.[12]

- Schwannoma [28]

- Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: Characterized by multiple compressible venous malformations involving the skin and visceral organs, particularly the gastrointestinal tract. Lesions are typically sporadic and may resemble glomangiomas in appearance. Gastrointestinal bleeding is a common complication and the primary cause of mortality.[7]

- Neuroma

- Hemangiopericytoma

- Angioleiomyoma

- Hamartoma

- Hemangioma [13]

- Subdermal mass

- Carcinoid tumors

- Hemangiopericytoma [19]

- Paraganglioma

- Maffucci syndrome: multiple subcutaneous vascular nodules on the toes and fingers

- Glomus tumor: seen in the adult population, painful, more commonly involves nail beds, and genetic/histology is cellular dominant with glomus cell infiltration.

- Spiradenoma

- Leiomyoma

- Venous malformation: compressible, painful

Prognosis

The prognosis for glomus cancers, particularly glomangiomas, is generally favorable when the lesion is completely excised, with low rates of recurrence and excellent symptom resolution.[3] However, the presence of metastasis, although extremely rare, is associated with a poor prognosis and may indicate malignant transformation or aggressive disease behavior.[10] Long-term outcomes depend on early diagnosis, complete surgical removal, and close follow-up to monitor for recurrence or complications.

Complications

Glomus tumors and GVMs may be associated with several clinical complications, though many are rare. Recurrence following surgical excision occurs in approximately 10% to 33% of cases, often due to incomplete removal or multifocality of the lesions.[9][13] While malignant transformation is exceedingly rare, certain features are associated with a higher risk. These include lesions measuring greater than 2 cm, deep anatomical location, invasion of muscle or bone, and elevated mitotic activity.[14] Although metastasis has been reported in isolated cases, it remains extremely uncommon.[10] Nerve compression is a possible complication, particularly when lesions grow in proximity to major nerve pathways, leading to pain, numbness, or functional impairment.[29] In rare scenarios, these lesions may become life-threatening due to progressive growth, bleeding, or obstruction of vital organs such as the airway or gastrointestinal tract.[12] An unusual case documented the development of Spitz nevi overlying a congenital glomuvenous malformation. One hypothesis suggests that hyperemia within the glomangioma may stimulate surrounding structures such as hair follicles. Additionally, mutations in the glomulin gene may play a contributing role in this process.[30]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be advised to monitor for any signs of lesion recurrence, increased size, bleeding, or new symptoms. Prompt follow-up with a healthcare provider is essential if such changes occur, as they may indicate progression or complications requiring further evaluation and possible intervention.

Pearls and Other Issues

Diagnosing GVMs can be challenging due to their clinical overlap with other vascular anomalies and soft tissue tumors, such as venous malformations, hemangiomas, blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, and other cutaneous lesions. Misdiagnosis may delay appropriate treatment and lead to unnecessary interventions. A thorough patient history, including family history, and a detailed physical examination are critical. Imaging studies and, when appropriate, histopathological analysis help confirm the diagnosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Glomangiomas often resemble other dermatologic lesions, such as papules or nodules, making accurate diagnosis a multidisciplinary effort. Optimal management requires collaboration among dermatologists, surgeons, and radiologists, especially when imaging or excision is indicated. Specialty care nurses play a vital role in coordinating follow-up, monitoring post-procedural outcomes, and delivering patient education regarding symptom monitoring and recurrence.

Radiologists contribute to diagnosis by identifying lesion depth, vascular involvement, or atypical features through imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging. Genetic counselors may also be involved in cases with a suspected familial pattern. An interprofessional team approach—facilitating timely referrals, shared decision-making, and integrated care planning—significantly improves diagnostic accuracy, treatment outcomes, and patient satisfaction.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Brouillard P, Boon LM, Mulliken JB, Enjolras O, Ghassibé M, Warman ML, Tan OT, Olsen BR, Vikkula M. Mutations in a novel factor, glomulin, are responsible for glomuvenous malformations ("glomangiomas"). American journal of human genetics. 2002 Apr:70(4):866-74 [PubMed PMID: 11845407]

Abbas A, Braswell M, Bernieh A, Brodell RT. Glomuvenous malformations in a young man. Dermatology online journal. 2018 Oct 15:24(10):. pii: 13030/qt2w54142d. Epub 2018 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 30677819]

Arens C, Dreyer T, Eistert B, Glanz H. Glomangioma of the nasal cavity. Case report and literature review. ORL; journal for oto-rhino-laryngology and its related specialties. 1997 May-Jun:59(3):179-81 [PubMed PMID: 9186975]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChatterjee JS, Youssef AH, Brown RM, Nishikawa H. Congenital nodular multiple glomangioma: a case report. Journal of clinical pathology. 2005 Jan:58(1):102-3 [PubMed PMID: 15623496]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMunoz C, Bobadilla F, Fuenzalida H, Goldner R, Sina B. Congenital glomangioma of the breast: type 2 segmental manifestation. International journal of dermatology. 2011 Mar:50(3):346-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04565.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21342169]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTewattanarat N, Srinakarin J, Wongwiwatchai J, Areemit S, Komvilaisak P, Ungarreevittaya P, Intarawichian P. Imaging of a glomus tumor of the liver in a child. Radiology case reports. 2020 Apr:15(4):311-315. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2019.12.014. Epub 2020 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 31988680]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeger M, Patel U, Mandal R, Walters R, Cook K, Haimovic A, Franks AG Jr. Glomangioma. Dermatology online journal. 2010 Nov 15:16(11):11 [PubMed PMID: 21163162]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSouza NGA, Nai GA, Wedy GF, Abreu MAMM. Congenital plaque-like glomangioma: report of two cases. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2017:92(5 Suppl 1):43-46. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175766. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29267443]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCabral CR, Oliveira Filho Jd, Matsumoto JL, Cignachi S, Tebet AC, Nasser Kda R. Type 2 segmental glomangioma--Case report. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2015 May-Jun:90(3 Suppl 1):97-100. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20152483. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26312686]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJha A, Khunger N, Malarvizhi K, Ramesh V, Singh A. Familial Disseminated Cutaneous Glomuvenous Malformation: Treatment with Polidocanol Sclerotherapy. Journal of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery. 2016 Oct-Dec:9(4):266-269. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.197083. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28163461]

Suárez-Magdalena O, Monteagudo B, Figueroa O, Gómez-Pérez MI. Glomulin gene c.157_161del mutation in a family with multiple glomuvenous malformations. International journal of dermatology. 2019 Feb:58(2):e43-e45. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14312. Epub 2018 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 30460983]

Boon LM, Mulliken JB, Enjolras O, Vikkula M. Glomuvenous malformation (glomangioma) and venous malformation: distinct clinicopathologic and genetic entities. Archives of dermatology. 2004 Aug:140(8):971-6 [PubMed PMID: 15313813]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGonçalves R, Lopes A, Júlio C, Durão C, de Mello RA. Knee glomangioma: a rare location for a glomus tumor. Rare tumors. 2014 Oct 27:6(4):5588. doi: 10.4081/rt.2014.5588. Epub 2014 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 25568752]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTony G, Hauxwell S, Nair N, Harrison DA, Richards PJ. Large plaque-like glomangioma in a patient with multiple glomus tumours: review of imaging and histology. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2013 Oct:38(7):693-700. doi: 10.1111/ced.12122. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24073652]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoon LM, Brouillard P, Irrthum A, Karttunen L, Warman ML, Rudolph R, Mulliken JB, Olsen BR, Vikkula M. A gene for inherited cutaneous venous anomalies ("glomangiomas") localizes to chromosome 1p21-22. American journal of human genetics. 1999 Jul:65(1):125-33 [PubMed PMID: 10364524]

Cullen RD, Hanna EY. Intranasal glomangioma. American journal of otolaryngology. 2000 Nov-Dec:21(6):402-4 [PubMed PMID: 11115526]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoujon E, Cordoro KM, Barat M, Rousseau T, Brouillard P, Vikkula M, Frieden IJ, Vabres P. Congenital plaque-type glomuvenous malformations associated with fetal pleural effusion and ascites. Pediatric dermatology. 2011 Sep-Oct:28(5):528-31. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01216.x. Epub 2010 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 21133993]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceScheithauer BW, Rodriguez FJ, Spinner RJ, Dyck PJ, Salem A, Edelman FL, Amrami KK, Fu YS. Glomus tumor and glomangioma of the nerve. Report of two cases. Journal of neurosurgery. 2008 Feb:108(2):348-56. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/2/0348. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18240933]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParker KL, Zervos MD, Donington JS, Shukla PS, Bizekis CS. Tracheal glomangioma in a patient with asthma and chest pain. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Jan 10:28(2):e9-e10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7942. Epub 2009 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 19858390]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAneiros-Fernandez J, Retamero JA, Husein-ElAhmed H, Carriel V, Ruiz Villaverde R, O'Valle F, Aneiros-Cachaza J. Smoothelin and WT-1 expression in glomus tumors and glomuvenous malformations. Histology and histopathology. 2017 Feb:32(2):153-160. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-782. Epub 2016 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 27184662]

Larsen DK, Madsen PV. [Glomus tumour of the distal phalanx]. Ugeskrift for laeger. 2018 Jul 23:180(30):. pii: V10170807. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30037386]

Flors L, Norton PT, Hagspiel KD. Glomuvenous malformation: magnetic resonance imaging findings. Pediatric radiology. 2015 Feb:45(2):286-90. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-3086-x. Epub 2014 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 24996811]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChirila M, Rogojan L. Glomangioma of the nasal septum: a case report and review. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2013 Apr-May:92(4-5):E7-9 [PubMed PMID: 23599117]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSharma JK, Miller R. Treatment of multiple glomangioma with tuneable dye laser. Journal of cutaneous medicine and surgery. 1999 Jan:3(3):167-8 [PubMed PMID: 10082598]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRivers JK, Rivers CA, Li MK, Martinka M. Laser Therapy for an Acquired Glomuvenous Malformation (Glomus Tumour): A Nonsurgical Approach. Journal of cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2016 Jan:20(1):80-3. doi: 10.1177/1203475415596121. Epub 2015 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 26177926]

Phillips CB, Guerrero C, Theos A. Nd:YAG laser offers promising treatment option for familial glomuvenous malformation. Dermatology online journal. 2015 Apr 16:21(4):. pii: 13030/qt4nv6k7bv. Epub 2015 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 25933083]

Jha A, Ramesh V, Singh A. Disseminated cutaneous glomuvenous malformation. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2014 Nov-Dec:80(6):556-8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.144200. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25382523]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBabeau F, Knafo S, Rigau V, Lonjon N. Paravertebral glomangioma mimicking a schwannoma. Neuro-Chirurgie. 2013 Aug-Oct:59(4-5):187-90 [PubMed PMID: 24367799]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJiga LP, Rata A, Ignatiadis I, Geishauser M, Ionac M. Atypical venous glomangioma causing chronic compression of the radial sensory nerve in the forearm. A case report and review of the literature. Microsurgery. 2012 Mar:32(3):231-4. doi: 10.1002/micr.20983. Epub 2012 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 22407591]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArica DA, Arica IE, Yayli S, Cobanoglu U, Akay BN, Anadolu R, Bahadir S. Spitz nevus arising upon a congenital glomuvenous malformation. Pediatric dermatology. 2013 May-Jun:30(3):e25-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01713.x. Epub 2012 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 22304367]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence