Introduction

The fusiform incision is a fundamental technique in surgical practice, particularly in the excision of cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions. This incision is frequently employed in dermatologic surgery, plastic and reconstructive procedures, and oncologic excisions due to its ability to convert round, oval, or irregular defects into linear closures, resulting in favorable cosmetic and functional outcomes. By removing tissue in a spindle-shaped or elliptical configuration with tapered ends, the fusiform incision facilitates direct primary closure while minimizing the risk of puckering, standing cones, or "dog ears" at the wound margins.

This geometric approach is critical for complete lesion excision and promoting healing along lines of minimal tension. Proper planning of the incision concerning relaxed skin tension lines, as well as accurate execution of width-to-length ratios and apex angulation, is essential to achieving optimal wound eversion, tension distribution, and scar aesthetics. This review discusses the principles of fusiform incision design, including key anatomic and biomechanical considerations, common pitfalls, and strategies for preventing contour deformities. Emphasis is placed on integrating sound surgical technique with aesthetic planning to ensure oncologic efficacy and patient satisfaction.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

This incisional technique can be used on the skin in virtually any anatomic location; however, the size and depth of the defects are limited by proximity to vital neurovascular structures and cosmetic subunit boundaries. For example, large fusiform excisions are not generally practical near the eye. Without specific modifications, they should not cross the eyelid's free margin or the lip's vermilion border.

In addition, the closure of these defects inherently creates tension. The orientation of the excision should be planned to align the closure with relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) or lines of maximum extensibility, minimizing tension that may distort free margins or vital structures and lead to cosmetic or functional abnormalities. Preoperative identification of RSTLs by observing natural skin folds or having the patient animate underlying facial muscles is a critical step.

Indications

Fusiform incision may be used to excise an entire lesion, or it can be used to remove just a portion of the involved tissue. The tapered ends of the resulting defect allow primary closure of the wound while minimizing "standing cone deformities" or "dog ears" at the ends of the incision. Modified fusiform techniques, such as S-plasty or Z-plasty, may be implemented to lengthen scars, alter their vector of tension, or avoid crossing cosmetic boundaries.[1]

Contraindications

While fusiform incisions are a mainstay in surgical practice for achieving linear closure and minimizing contour deformities, several contraindications and limitations must be considered. Absolute contraindications are rare, but relative contraindications are more common and often dependent on the patient's anatomy, clinical condition, and lesion characteristics. A primary consideration is insufficient tissue laxity in the area of planned excision. In regions with limited skin mobility—such as the lower extremities, scalp, or over bony prominences—attempting a fusiform closure may result in undue tension, wound dehiscence, or ischemia of the wound edges.

Similarly, lesions near cosmetically or functionally sensitive structures, such as the eyelids, lips, nostrils, or genitalia, may require alternative closure strategies to avoid distortion or functional impairment. Fusiform incisions may also be suboptimal when lesion orientation prevents alignment with RSTLs, increasing the risk of poor cosmetic outcomes or hypertrophic scarring. In malignancies with poorly defined borders, such as melanoma in situ or high-risk non-melanoma skin cancers, an elliptical excision may not provide adequate margins, necessitating a wider excision or staged techniques, like Mohs micrographic surgery.

Additionally, caution should be exercised in patients on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy, those with inherited or acquired bleeding disorders, or those with active skin infections at the surgical site. The risk-benefit ratio must be carefully weighed in cases of significant systemic coagulopathy or critical illness. Consultation with the appropriate specialist, such as a cardiologist or hematologist, is essential in cases of uncertainty. Clinicians should also assess patients for allergies to local anesthetics, topical preparations, or dressing materials, as these can impact intraoperative and postoperative management. While fusiform incisions are broadly applicable and highly effective, careful patient selection and attention to anatomic, functional, and systemic factors are essential to ensure safe and optimal outcomes.

Equipment

Essential equipment is minimal and includes the following:

Preoperatively

- Local anesthetic (typically lidocaine 0.5% with epinephrine 1:200,000 and buffered with sodium bicarbonate)

- 3- or 5-mL syringe(s)

- 27- or 30-gauge needle(s)

- Antiseptic scrub (eg, chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine)

- Surgical skin marker

Intraoperatively

- Sterile drape

- Scalpel with #15 blade

- Toothed forceps (eg, Adson)

- Suture scissors

- Needle holders

- Normal saline

- Sterile gauze

- Absorbable suture (for subcutaneous/deep stitches)

- Cutaneous suture (nonabsorbable or absorbable)

- Electrosurgical or electrocautery device (should be available for hemostasis)

Postoperatively

- Nonstick dressing

- Medical-grade sterile ointment (the author prefers sterile petrolatum to antibiotic ointment, as significant numbers of patients develop allergies to bacitracin and neomycin, while their ability to decrease infection is minimal). Recent studies' results support the notion that sterile petrolatum is as effective as antibiotic ointments in preventing postoperative infections for clean surgical wounds, and it avoids the risk of allergic contact dermatitis.[2]

- Gauze or other material to use in a bulky pressure dressing

- Adhesive dressing, preferably hypoallergenic and stretchy

Personnel

While a fusiform incisional surgery can be performed as a solo procedure, the presence of a skilled surgical assistant significantly enhances both efficiency and safety. An assistant can facilitate the operation by retracting tissue for optimal visualization, managing hemostasis through suction or cautery, cutting sutures, and applying dressings promptly and effectively. These contributions streamline the surgical process and reduce operative time and surgeon fatigue. In complex or cosmetically sensitive cases, a well-trained assistant can help maintain field sterility, anticipate instrument needs, and support precise wound closure, ultimately contributing to improved surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Preparation

Most minor, routine skin surgeries do not require prophylactic antibiotics. Due to the risk of adverse events associated with perioperative empiric antibiotic therapy, referring to the current American Academy of Dermatology guidelines for each patient is recommended, using antibiotics only when indicated.[3] Antithrombotic medications may generally be continued for most cutaneous surgeries to prevent thromboembolic events. However, the decision to hold a patient's anticoagulant or antiplatelet should be made on a case-by-case basis and incorporate the individual's risk factors.[4]

Once ready, the surgical site should be examined with the patient in a neutral or natural position, usually sitting erect. The long axis of the incision is generally chosen to run parallel to the relaxed skin tension lines. The skin is scrubbed with alcohol, and the planned incision is drawn with a surgical marker. The patient is then placed in a comfortable position that allows the surgeon optimal access and lighting.

Technique or Treatment

The fusiform, or elliptical, excision is a foundational surgical technique for removing cutaneous lesions and achieving a linear, tension-minimized closure. The process begins with proper planning: the lesion is first outlined with the required clinical margins, and the long axis of the planned defect is aligned parallel to RSTLs for optimal cosmetic results. The incision should be designed with straight lines that run tangential to the lesion margins, rather than rounded edges, as this helps produce sharper apical angles and reduces the risk of standing cones or "dog ears".

After sterile preparation, the tissue is infiltrated with a local anesthetic. The surgeon then stretches the skin perpendicular to the incision line, using the scalpel hand as one point of traction and 2 fingers of the opposite hand as the other 2 points to stabilize the field. The incision begins at 1 apex, using the tip of the blade to puncture the skin, and proceeds with the rounded belly of the blade in a single, smooth motion to the desired depth, typically to the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat.[5] Throughout the cut, the scalpel should be held perpendicular (at a 90-degree angle) to the skin surface to create vertical wound edges, which help maintain wound eversion and minimize the risk of an inverted or depressed scar. Once the elliptical incision is completed, the lesion is excised by sharply dissecting the specimen from its undersurface using a scalpel or scissors, maintaining a uniform depth and plane.[5] If the wound base is uneven following excision, additional tissue may be trimmed to create a flat plane suitable for closure.

Hemostasis is typically achieved through electrocoagulation. The wound is closed in a layered fashion, beginning with absorbable sutures in the subcutaneous tissue and dermis. These deep sutures provide structural strength, reduce dead space, and help prevent dehiscence. Undermining, if needed, should be limited to the minimum necessary to allow suture placement and modest tissue mobility. Excessive undermining increases the risk of hematoma or seroma formation and has not been shown to improve outcomes in most cases.[6]

Depending on location and wound tension, superficial closure is performed with either absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures. In low-tension areas or small incisions, tissue adhesive may suffice.[7][8] Sometimes, superficial closure alone may be appropriate, but deep sutures are preferred when tension or tissue movement is present. When using absorbable sutures for superficial closure, it's critical to select a material with sufficient tensile strength and duration to support the wound through its early healing phase.[9]

Skin hooks, rather than toothed forceps, are recommended for tissue handling, especially in cosmetically sensitive areas, as they reduce crush injury to the wound edges. Once the closure is complete, a sterile pressure dressing is applied for 24 to 48 hours to minimize bleeding and promote wound healing. The incision is coated with sterile petrolatum, which is preferred over antibiotic ointments like bacitracin or neomycin due to the risk of allergic contact dermatitis and lack of proven benefit in preventing infection.[10] A nonadhesive dressing is placed directly over the wound, followed by fluffed gauze or cotton to apply pressure, and secured with elastic tape strips oriented perpendicular to the incision line to offload tension and support edge approximation during the healing process.

Suture removal timing depends on the location and the tension of the wound. Typically, sutures can be removed after 5 to 7 days on the face, while on the trunk or extremities, 10 to 14 days is generally considered safer, depending on physical activity levels and tissue quality. These guidelines help minimize scarring and support favorable healing outcomes. By carefully following these principles—precise incision design, atraumatic tissue handling, layered closure, limited undermining, and strategic dressing application—clinicians can maximize the' clinical and cosmetic success of fusiform incisions.

Complications

As with other forms of incisional surgery, the main risks include bleeding, hematoma/seroma formation, scar formation (including hypertrophic or keloid scars), and infection. Other risks include damage to underlying structures such as nerves or major vessels, aesthetic disfigurement, and functional impairment. Wound dehiscence and tissue necrosis are less common but can occur, particularly in high-tension closures or in patients with compromised healing. Careful preparation and meticulous surgical technique minimize these risks.

Clinical Significance

The fusiform incision is a cornerstone technique in dermatologic and surgical practice, widely used for the excision of round or oval lesions, facilitating linear, tension-minimized closure. Clinically, its primary significance lies in its ability to convert irregular or circular defects into a spindle-shaped wound with tapered ends, thereby enabling direct primary closure with reduced risk of puckering, dog-ear formation, or wound tension. This makes it especially valuable in cosmetically and functionally sensitive areas, where the aesthetics of the final scar and preservation of nearby anatomical structures are critical. The technique is prevalent in removing benign and malignant skin lesions, soft tissue neoplasms, scars, and inflammatory dermatoses, where histologic margin control and tissue architecture are key to diagnosis and treatment planning.

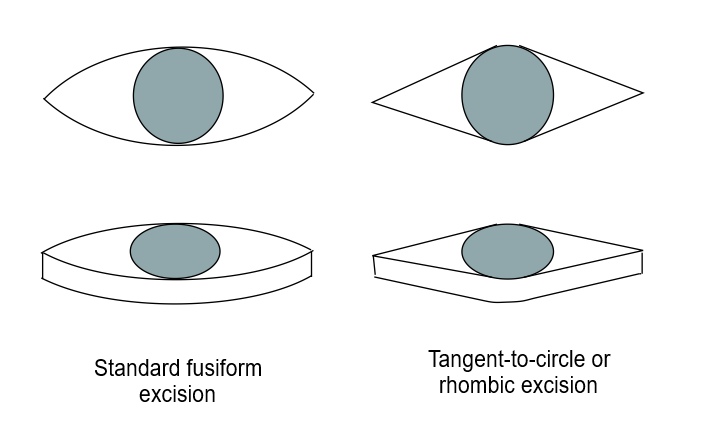

Fusiform incisions are typically designed by first outlining the lesion with appropriate clinical margins, usually forming a circle or oval. The incision includes tissue within the marked boundaries and adds extensions at either end to create the tapered, elliptical shape necessary for optimal closure. Two common variations exist; the most frequently taught version includes 2 smoothly curved sides, forming a classic elliptical shape. However, a more efficient method employs straight lines converging on the rounded central portion, producing a rhomboid appearance with only one curved margin, typically aligned with the lesion (see Image. Fusiform Incision and Excision).[11][12] This approach allows for more acute apical angles, minimizing redundant tissue at the ends of the incision and reducing the likelihood of “dog ears” or standing cones. However, these narrower angles require a longer incision to preserve an appropriate length-to-width ratio. A 3:1 ratio generally achieves an apical angle of approximately 30 degrees, which balances aesthetic closure and tissue conservation; however, anatomical location and skin laxity may warrant adjustments.[13]

Beyond lesion removal, fusiform incisions have important diagnostic applications. They can be used to obtain a cross-sectional view of a broader tissue area, especially in lesions with histologic transition zones, such as a keratoacanthoma at its periphery, to help differentiate it from more aggressive neoplasms like squamous cell carcinoma. This approach allows for preserving the specimen’s architectural integrity, providing pathologists with essential diagnostic information while maintaining the ability to achieve linear closure with minimal tension.[14] Similarly, elongated fusiform specimens can be used to evaluate large pigmented lesions, providing a generous tissue sample for histologic assessment without creating disproportionately large defects. In sum, the fusiform incision is a surgical tool for effective excision and closure and a versatile technique with both therapeutic and diagnostic applications. When properly executed, considering skin tension lines, defect geometry, and surrounding anatomy, it enables superior cosmetic results, low complication rates, and optimal histologic yield, making this incision indispensable in surgical and dermatologic practice.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective performance of a fusiform incision requires surgical precision and interprofessional collaboration to ensure patient-centered care, optimal outcomes, and procedural safety. Physicians and advanced clinicians must possess strong skills in clinical decision-making, lesion assessment, and geometric planning to design incisions that align with relaxed skin tension lines and anatomical landmarks. Proper tissue handling, incision technique, and layered closure during the procedure are essential to minimize scarring and complications. Nurses play a crucial role in preoperative preparation, intraoperative assistance, and postoperative wound care, encompassing patient education and the early identification of infections or dehiscences. Pharmacists contribute by reviewing medication histories, optimizing perioperative pain control, and preventing adverse reactions, especially in patients with allergies to topical antibiotics or local anesthetics.

Interprofessional communication and coordinated workflows are critical throughout the care continuum. Preoperative discussions between clinicians help assess surgical risk and clarify procedural goals. Intraoperatively, real-time coordination between the surgical provider and assisting staff—such as medical assistants or scrub nurses—ensures sterile technique, efficient instrument handling, and accurate specimen labeling. Postoperatively, coordinated discharge instructions and follow-up planning assure continuity of care and reinforce wound management practices. When histologic analysis is needed, collaboration with pathologists supports accurate diagnosis and margin assessment. This team-based approach improves safety, enhances patient satisfaction, and promotes shared accountability across disciplines.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The healthcare team collaborates to ensure patient safety and procedural success. Key interventions include:

- Preoperative

- Verifying the correct patient, procedure, and site

- Reviewing allergies and medications

- Preparing the sterile field and equipment

- Intraoperative

- Assists with tissue retraction and hemostasis, passing instruments, and cutting sutures

- Ensures the correct handling, labeling, and submission of the surgical specimen

- Postoperative

- Applies the final dressing

- Provides clear verbal and written wound care instructions and schedules the follow-up appointment

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Vigilant monitoring by the entire team is crucial for identifying complications early. Key monitoring tasks include:

- Intra- and postoperative

- Observe for excessive bleeding, patient discomfort, or vasovagal symptoms.

- Check the final dressing for any immediate bleed-through before discharge.

- Postdischarge and follow-up

- Triage patient calls to screen for early signs of infection (eg, purulent drainage, fever) or hematoma (eg, severe pain, swelling).

- During follow-up, the team assesses the wound for proper healing and reports any concerns, such as dehiscence or infection, to the physician.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Zito PM, Jawad BA, Hohman MH, Mazzoni T. Z-Plasty. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939552]

Lin WL, Wu LM, Nguyen TH, Lin YH, Chen CJ, Huang WT, Guo HR, Chen YH, Chuang CH, Chang PC, Hung HK, Chen SH. Topical Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Preventing Surgical Site Infections of Clean Wounds: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Surgical infections. 2024 Feb:25(1):32-38. doi: 10.1089/sur.2023.182. Epub 2023 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 38112687]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLauck KC, Cho SW, Rickstrew J, Tolkachjov SN. Adverse events after empiric antibiotic administration in dermatologic surgery: A global, propensity-matched, retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2024 May:90(5):1065-1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.01.020. Epub 2024 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 38266681]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTrager MH, Gordon ER, Humphreys TR, Samie FH. Part 1: Management of antithrombotic medications in dermatologic surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2025 Mar:92(3):389-404. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.01.096. Epub 2024 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 38735483]

Vujevich JJ, Kimyai-Asadi A, Goldberg LH. The four angles of cutting. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2008 Aug:34(8):1082-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34212.x. Epub 2008 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 18462418]

Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: Part I. Cutting tissue: incising, excising, and undermining. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2015 Mar:72(3):377-87. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.048. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25687309]

Byrne M, Aly A. The Surgical Suture. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2019 Mar 14:39(Suppl_2):S67-S72. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz036. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30869751]

Ge L, Chen S. Recent Advances in Tissue Adhesives for Clinical Medicine. Polymers. 2020 Apr 18:12(4):. doi: 10.3390/polym12040939. Epub 2020 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 32325657]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMiller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: Part II. Repairing tissue: suturing. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2015 Mar:72(3):389-402. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25687310]

Choi C, Vafaei-Nodeh S, Phillips J, de Gannes G. Approach to allergic contact dermatitis caused by topical medicaments. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2021 Jun:67(6):414-419. doi: 10.46747/cfp.6706414. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34127463]

Raveh Tilleman T, Tilleman MM, Krekels GA, Neumann MH. Skin waste, vertex angle, and scar length in excisional biopsies: comparing five excision patterns--fusiform ellipse, fusiform circle, rhomboid, mosque, and S-shaped. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2004 Mar:113(3):857-61 [PubMed PMID: 15108876]

Goldberg LH, Alam M. Elliptical excisions: variations and the eccentric parallelogram. Archives of dermatology. 2004 Feb:140(2):176-80 [PubMed PMID: 14967789]

Moody BR, McCarthy JE, Sengelmann RD. The apical angle: a mathematical analysis of the ellipse. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2001 Jan:27(1):61-3 [PubMed PMID: 11231247]

Pardasani AG, Leshin B, Hallman JR, White WL. Fusiform incisional biopsy for pigmented skin lesions. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2000 Jul:26(7):622-4 [PubMed PMID: 10886267]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence