Introduction

Throughout history, numerous investigators have reported a high prevalence of benign palatal mucosal cysts in newborns (see Image. Palatal Cysts of the Newborn). In 1880, Prague pediatrician Alois Epstein first described the presence of small nodules in the oral cavities of newborns, which were later termed "Epstein pearls."[1][2][3][4] However, it was not until 1967 that Alfred Fromm conducted the largest study on oral inclusion cysts, examining 1367 newborns. Fromm classified the cysts by location and composition into Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and dental lamina cysts, concluding that these lesions are common in infants.[5]

Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and gingival cysts of the newborn (also known as dental lamina cysts) are remarkably similar lesions that have often been confused or used interchangeably over time. They share more similarities than differences, including clinical appearance, histology, and natural history of evolution; however, they differ in their embryological origins.[6] Currently, the term "palatal cysts" refers to Epstein pearls and Bohn nodules, whereas "gingival cysts" refers to dental lamina cysts.[7][8][9][10]

Differentiating among these 3 entities clinically is not always possible or necessary, as diagnosis relies primarily on their clinical appearance, and the treatment approach is the same for all. However, healthcare professionals caring for newborns should be well-informed about these benign, self-resolving lesions to distinguish them from other conditions that require invasive management, such as congenital epulis of the newborn and natal or neonatal teeth.[6][11]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn are developmental lesions that arise from the entrapment of epithelial remnants during embryogenesis.[12] These inclusion cysts—commonly classified as Epstein pearls (palatal cysts), Bohn nodules (gingival cysts located on the buccal and lingual aspects of the alveolar ridges), and dental lamina cysts (gingival cysts on the alveolar ridge crest)—result from residual epithelial tissue or dental lamina remnants that become trapped during palatal shelf fusion or alveolar ridge formation.[3][13]

Epstein Pearls

These are benign, keratin-filled cysts that develop from epithelial remnants trapped along the midline of the hard palate during the embryologic fusion of the palatal shelves. Epstein pearls are typically located on the median palatal raphe, and they commonly appear in newborns as small, white or yellowish papules.[6]

Bohn Nodules

These are benign, self-limiting cystic lesions that are commonly found in the oral cavity of newborns. They originate from remnants of minor salivary gland epithelium and are typically located along the buccal and lingual aspects of the alveolar ridges, away from the midline.[13][14]

Dental Lamina Cysts

In newborns, dental lamina cysts appear as benign, keratin-filled lesions that arise from remnants of the dental lamina—an epithelial structure involved in early tooth development. They are typically located on the crest of the alveolar ridges, either maxillary or mandibular, and often appear as multiple small, white or yellowish papules.[13]

Epidemiology

Palatal cysts are observed in approximately 30% to 50% of newborns,[6] and they are often considered a normal anatomic finding due to their high frequency. Gingival cysts are slightly less prevalent, with reported rates ranging from 13% to 50% in newborns.[11] A study found that palatal and alveolar cysts are more frequent in full-term infants (30%) compared to premature infants (9%). The risk of developing palatal and maxillary alveolar cysts increases with higher birth weight, gestational age, and postnatal age. No significant differences were observed in this study related to gender or race.[15][16][17]

Pathophysiology

Palatal development begins near the end of the eighth week of gestation. Each maxillary process forms a lateral palatine process within the oral cavity. These shelf-like structures grow horizontally from the lateral aspects of the mouth toward the midline and downward. Between the tenth and eleventh weeks of gestation (in utero), the lateral palatine processes fuse with each other, the smaller premaxillary process, and the nasal septum. Palatal fusions are usually complete by the end of the fourth month of gestation.

At this stage, a theory suggests that the epithelium trapped between the palatal shelves and the nasal process forms cysts known as "Epstein pearls." Another theory suggests these cysts may originate from epithelial remnants of the minor salivary glands in the palate. Additionally, remnants of the dental lamina are believed to persist within the alveolar ridge mucosa after tooth development, where they can proliferate to form keratinized cysts.[13][18]

Histopathology

Palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn are histologically characterized by keratin-filled cystic spaces lined with thin, stratified squamous epithelium. The epithelial lining is typically 2 to 3 cell layers thick, nonkeratinized or parakeratinized, and lacks rete ridges. The cyst lumen contains desquamated keratin, and the surrounding connective tissue appears unremarkable, with no signs of inflammation.[13] Although these cysts share similar microscopic features, such as thin epithelial linings and keratin content, they differ in anatomic location and embryologic origin.[13]

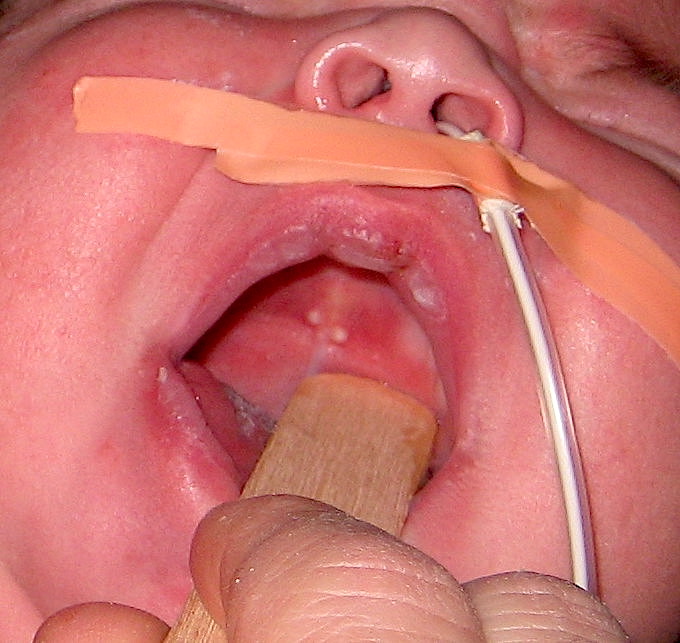

History and Physical

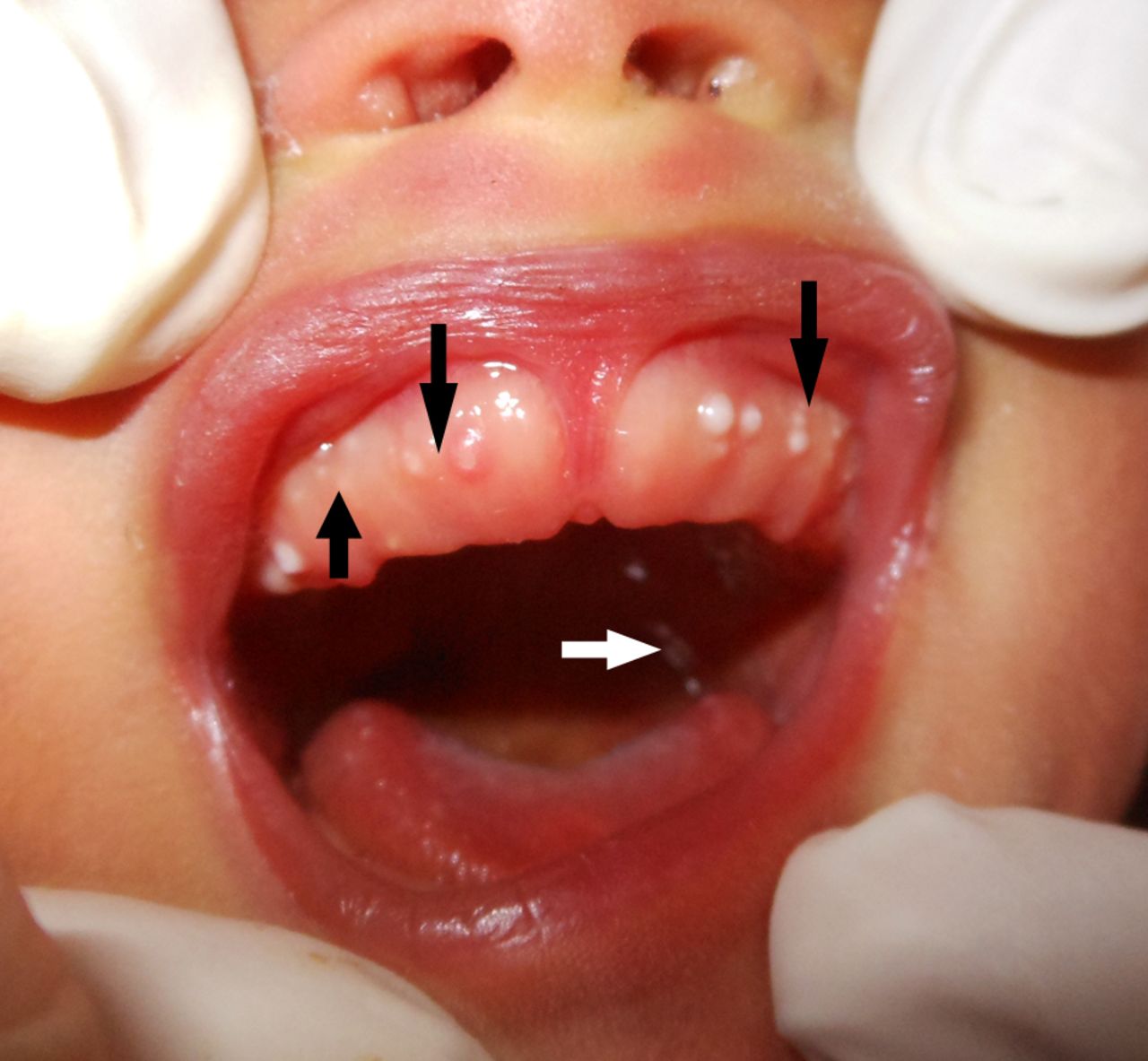

Palatal cysts, including Epstein pearls and Bohn nodules, are small, painless, white to yellow, firm, non-fluctuant papules typically measuring 1 to 3 millimeters in diameter. They often appear in clusters of 2 to 6 lesions but may also present as solitary cysts.[6] Although the distinction is not clinically significant, these cysts are named based on their location. Epstein pearls are found along the mid-palatine raphe and near the junction of the hard and soft palate (see Image. Epstein Pearls). In contrast, Bohn nodules are located on the buccal and lingual surfaces of the alveolar ridges (see Image. Multiple Bohn Nodules on the Maxillary Alveolar Ridge).[6]

Gingival cysts present as small, whitish papules measuring 2 to 3 millimeters in newborns. They can be either isolated or multiple and are typically located on the crest of the alveolar ridge.[3] They are more commonly found in the maxilla than the mandible and share the same histological features as palatal cysts. In individuals with cleft palate, palatal cysts appear with a similar distribution to those without cleft palate, except they are located at the margins of the palatal shelves rather than along the midline.[19] Epstein pearls resemble the equivalent of milia, which are white papules caused by retention of sebum and keratin in the hair follicles, and are frequently seen on neonates' faces.

Evaluation

Palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn are typically diagnosed based solely on clinical features.[3] Laboratory tests and imaging are not required, as these cysts do not affect the underlying bone.

Treatment / Management

Treatment or surgical intervention is unnecessary, as these lesions typically regress spontaneously within a few weeks to months.[6] They are rarely observed beyond 3 months of age. Parental concerns should be addressed through reassurance and, if needed, routine follow-up.

Differential Diagnosis

Palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn should be differentiated from natal and neonatal teeth, as well as congenital epulis. Natal and neonatal teeth are rare and typically appear in the lower central incisor region.[20] Natal and neonatal teeth are often mobile due to absent or underdeveloped roots and may require extraction to avoid accidental ingestion.[3]

Natal and neonatal teeth may be associated with developmental anomalies and recognized syndromes, such as Rubinstein-Taybi, Hallerman-Streiff, Ellis-van Creveld, Pierre-Robin sequence, pachyonychia congenita, short-rib polydactyly syndrome type II, steatocystoma multiplex, cyclopia, and Pallister-Hall syndrome. Genetic evaluation is warranted if the patient presents with additional dysmorphic features.

Congenital epulis is a benign pedunculated soft-tissue mass ranging from 1 millimeter to several centimeters in diameter. The swelling is typically located in the anterior maxillary ridge and present at birth. Occasionally, it is diagnosed in utero.[11] These lesions can grow large enough to interfere with breathing and feeding, and are usually surgically excised within the first weeks of life.[11] They do not spontaneously regress or recur after surgical removal.[21]

Prognosis

Palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn typically involute or spontaneously rupture, releasing their keratin contents into the oral cavity within the first few weeks to months of postnatal life. These lesions are rarely observed beyond 3 months of age. However, some cystic epithelium may remain dormant in the adult gingiva. Palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn are believed to resolve spontaneously as their cystic walls fuse with the oral epithelium, allowing the contents to be discharged.[3]

Complications

Palatal and gingival cysts are self-resolving lesions that are usually discovered incidentally and are not typically associated with further complications. However, in some cases, large or numerous cysts may occasionally interfere with feeding, potentially causing poor weight gain or feeding difficulties. These cysts can occasionally be mistaken for more severe oral pathologies, which may lead to unnecessary interventions or parental anxiety. In rare instances, if cysts become infected or persist beyond infancy, further evaluation or minor surgical intervention may be necessary. Although complications are uncommon, accurate diagnosis and monitoring are crucial to ensure appropriate management and provide reassurance to parents.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Clinicians should explain that palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn are transient, benign, and asymptomatic lesions that do not interfere with feeding or tooth eruption. Caregivers should be advised against attempting to rupture or manipulate the cysts at home, as this can cause infection or injury. Routine pediatric follow-ups are generally sufficient for monitoring the cysts and maintaining proper oral health.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn include:

- These oral inclusion cysts are typically benign and self-limiting, but they are sometimes overlooked, misidentified, or misdiagnosed by healthcare professionals.

- Gingival cysts can be mistaken for pseudomembranous candidiasis, which may lead to unnecessary use of antifungal medication.[11]

- Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and gingival cysts observed in newborns are all managed primarily by reassuring parents of their benign and self-limiting nature.

- Although the above 3 cysts share the same clinical aspects, histopathology, evolution, and treatment, they are believed to have different etiologies and locations in the oral cavity.

- Oral inclusion cysts are identified as Epstein pearls when located along the midpalatine raphe or at the junction between the hard and soft palate; as Bohn nodules when found on the vestibular or lingual aspects of the alveolar ridge; and as gingival cysts when present on the crest of the alveolar ridges.

- Differential diagnoses include natal and neonatal teeth, as well as congenital epulis of the newborn.[22]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn requires a collaborative, patient-centered approach involving dentists, physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals. Key competencies include accurate assessment and clear communication, as well as providing reassurance to caregivers. A unified strategy should emphasize noninvasive observation, ethical education to discourage unnecessary treatment, and prompt referral if atypical features are identified.

Responsibilities are distributed through coordinated care—dentists and physicians are responsible for diagnosis, nurses monitor the infant and provide caregiver support, and pharmacists promote safe practices. All healthcare team members contribute to transparent communication. Interprofessional collaboration ensures consistent messaging, enhances patient safety, reduces parental anxiety, and improves outcomes by aligning care with best practices and developmental milestones.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Epstein Pearls. Epstein pearls are visible on the palatal mucosa in a 5-week-old infant.

Sghael, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Zeman J, Zeman L. Short view on origins of paediatric health care in Prague. Casopis lekaru ceskych. 2018 Summer:157(3):113-116 [PubMed PMID: 30441945]

Haveri FT, Inamadar AC. A cross-sectional prospective study of cutaneous lesions in newborn. ISRN dermatology. 2014:2014():360590. doi: 10.1155/2014/360590. Epub 2014 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 24575304]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSingh RK, Kumar R, Pandey RK, Singh K. Dental lamina cysts in a newborn infant. BMJ case reports. 2012 Oct 9:2012():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007061. Epub 2012 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 23048002]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGupta P, Faridi MM, Batra M. Physiological skin manifestations in twins: association with maternal and neonatal factors. Pediatric dermatology. 2011 Jul-Aug:28(4):387-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01434.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21793881]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFromm A. Epstein's pearls, Bohn's nodules and inclusion-cysts of the oral cavity. Journal of dentistry for children. 1967 Jul:34(4):275-87 [PubMed PMID: 5342399]

Lewis DM. Bohn's nodules, Epstein's pearls, and gingival cysts of the newborn: a new etiology and classification. Journal - Oklahoma Dental Association. 2010 Mar-Apr:101(3):32-3 [PubMed PMID: 20397339]

de Carvalho JF, Pereira RM, Shoenfeld Y. Pearls in autoimmunity. Auto- immunity highlights. 2011 May:2(1):1-4. doi: 10.1007/s13317-011-0016-x. Epub 2011 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 26000114]

Gokdemir G, Erdogan HK, Köşlü A, Baksu B. Cutaneous lesions in Turkish neonates born in a teaching hospital. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2009 Nov-Dec:75(6):638. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.57742. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19915262]

Sachdeva M, Kaur S, Nagpal M, Dewan SP. Cutaneous lesions in new born. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2002 Nov-Dec:68(6):334-7 [PubMed PMID: 17656992]

Moosavi Z, Hosseini T. One-year survey of cutaneous lesions in 1000 consecutive Iranian newborns. Pediatric dermatology. 2006 Jan-Feb:23(1):61-3 [PubMed PMID: 16445415]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBilodeau EA, Hunter KD. Odontogenic and Developmental Oral Lesions in Pediatric Patients. Head and neck pathology. 2021 Mar:15(1):71-84. doi: 10.1007/s12105-020-01284-3. Epub 2021 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 33723756]

Rezende KM, de Barros Gallo C, Nogueira GP, Corraza AC, Haddad AE, Gallottini M, Bönecker M. Retrospective study of oral lesions biopsied in babies and toddlers. Oral diseases. 2024 Apr:30(3):1242-1244. doi: 10.1111/odi.14552. Epub 2023 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 36825395]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSummersgill KF. Pediatric Oral Pathology: Odontogenic Cysts. Pediatric and developmental pathology : the official journal of the Society for Pediatric Pathology and the Paediatric Pathology Society. 2023 Nov-Dec:26(6):609-620. doi: 10.1177/10935266231176245. Epub 2023 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 37212213]

Cizmeci MN, Kanburoglu MK, Kara S, Tatli MM. Bohn's nodules: peculiar neonatal intraoral lesions mistaken for natal teeth. European journal of pediatrics. 2014 Mar:173(3):403. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2173-6. Epub 2013 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 24132386]

Donley CL, Nelson LP. Comparison of palatal and alveolar cysts of the newborn in premature and full-term infants. Pediatric dentistry. 2000 Jul-Aug:22(4):321-4 [PubMed PMID: 10969441]

Valdelice Cruz P, Bendo CB, Perez Occhi-Alexandre IG, Martins Paiva S, Pordeus IA, Castro Martins C. Prevalence of Oral Inclusion Cysts in a Brazilian Neonatal Population. Journal of dentistry for children (Chicago, Ill.). 2020 May 15:87(2):90-97 [PubMed PMID: 32788002]

Zen I, Soares M, Sakuma R, Inagaki LT, Pinto LMCP, Dezan-Garbelini CC. Identification of oral cavity abnormalities in pre-term and full-term newborns: a cross-sectional and comparative study. European archives of paediatric dentistry : official journal of the European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry. 2020 Oct:21(5):581-586. doi: 10.1007/s40368-019-00499-5. Epub 2019 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 31811584]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMarini R, Chipaila N, Monaco A, Vitolo D, Sfasciotti GL. Unusual symptomatic inclusion cysts in a newborn: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2014 Sep 21:8():314. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-314. Epub 2014 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 25241967]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRichard BM, Qiu CX, Ferguson MW. Neonatal palatal cysts and their morphology in cleft lip and palate. British journal of plastic surgery. 2000 Oct:53(7):555-8 [PubMed PMID: 11000069]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKumar A, Grewal H, Verma M. Dental lamina cyst of newborn: a case report. Journal of the Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry. 2008 Dec:26(4):175-6 [PubMed PMID: 19008628]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTucker MC, Rusnock EJ, Azumi N, Hoy GR, Lack EE. Gingival granular cell tumors of the newborn. An ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 1990 Aug:114(8):895-8 [PubMed PMID: 2375666]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBinti Shuhairi NN, Bt Abdul Jalil A, Lau SH, Bt Mohd Ghazali S, Kee CC. A retrospective analysis of oral and maxillofacial biopsied specimens in Malaysian newborns and infants. International journal of paediatric dentistry. 2021 Jul:31(4):496-503. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12719. Epub 2020 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 32815206]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence