Introduction

Croup is a common respiratory illness in children younger than 6, with peak incidence between 6 months and 3 years. This infection is most common in the fall and early winter but can occur year-round. Although typically mild and self-limiting, croup occasionally causes significant upper airway obstruction and respiratory distress.[1]

Croup includes the spectrum of laryngotracheitis, laryngotracheobronchitis, and laryngotracheal bronchopneumonitis. The infection affects the larynx, trachea, and bronchi, leading to a characteristic barking cough and inspiratory stridor. Parainfluenza virus (PIV) is the most common cause, though bacterial infections can also be responsible. Diagnosis is primarily clinical, but clinicians must first exclude life-threatening conditions such as epiglottitis or airway foreign bodies. Most patients should be treated with corticosteroids, whereas epinephrine is reserved for moderate-to-severe cases.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Croup is most commonly caused by viral infections, though bacterial cases can occur. The typical incubation period ranges from 2 to 6 days.

Viral Etiology

Parainfluenza virus, primarily types 1 and 2, is the most common cause of croup. Sporadic cases of croup caused by parainfluenza type 3 are less common but more severe than those caused by types 1 and 2.[CDC. Clinical Overview of Human Parainfluenza Viruses (HPIVs) June 5, 2024].

In a study evaluating the etiological agent causing croup in 144 children who presented to the emergency department with stridor and hoarseness, 80% of patients with croup and 71% of controls tested positive for a viral infection. Children with croup symptoms had more positive results for PIV 1 and 2 and fewer positive results for respiratory syncytial virus. Positive tests for influenza A, rhinoviruses, and enteroviruses were present equally in croup and control patients. The study concluded that PIV1 and PIV2 were the most common etiological agents associated with croup.[2]

Other viral causes include influenza A and B, adenovirus, rhinovirus, SARS-CoV-2, respiratory syncytial virus, and measles. Less frequently, enteroviruses such as coxsackie, echovirus, and herpes simplex can cause sporadic cases of mild croup. SARS-CoV-2 has become a common cause of croup, especially the Omicron variant. Croup caused by SARS-CoV-2 may present with severe symptoms requiring intense treatment and hospitalization compared to croup caused by other viral etiologies.[3]

Bacterial Etiology

Bacterial croup can lead to several conditions, including bacterial tracheitis, laryngotracheobronchitis, laryngotracheobronchopneumonitis, and diphtheria, which is caused by Corynebacterium diphtheria. Secondary bacterial infections, particularly bacterial tracheitis, can occur due to Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Mycoplasma pneumoniae can also cause a mild croup-like illness.[4]

Epidemiology

The majority of patients with croup, more than 85%, exhibit mild symptoms, and severe croup is rare, fewer than 1%. In the United States, croup accounts annually for approximately 7% of pediatric hospitalizations, with fewer than 3% of admitted cases requiring intubation, and contributes to up to 15% of emergency department visits among children younger than 5.[5]

Croup typically affects children between the ages of 6 months and 3 years, but can occur as early as 3 months and up to 15 years. The annual incidence is approximately 532 cases per 100,000 individuals, affecting 3% of children younger than 5 globally. Croup rarely occurs in adults. PIV is responsible for more than two-thirds of croup infections. Croup is more common in boys than in girls, with a 1.5:1 ratio, and shows no preference for any race. Croup is more prevalent in resource-limited countries, likely due to a higher proportion of children younger than 6 and suboptimal nutritional status.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology underlying airway inflammation is responsible for the symptoms of croup. Clinically, croup is classified into viral, spasmodic, and recurrent atypical forms. Viral or classic croup is typically a self-limited illness and resolves within 3 days.[6]

Spasmodic croup mostly occurs at night, with an abrupt onset and a short duration. Episodes may recur within the same night and persist for the next 2 to 3 nights. Spasmodic croup is sometimes called allergic croup, as it may be associated with a positive family history of allergies and atopy. The episodic symptoms of spasmodic croup in an otherwise healthy child differentiate it from viral croup. Symptoms are continuous, not intermittent, in viral croup. The typically benign yet dramatic presentation of spasmodic croup typically resolves with supportive care, including comfort measures and humidified air.[7]

Recurrent or atypical croup is characterized by frequent episodes of croup-like symptoms, occurring more than twice per year, with severe or prolonged symptoms that may occur outside the typical age range.[8] This pattern raises the suspicion of another underlying condition, such as congenital airway abnormalities, gastroesophageal reflux, eosinophilic esophagitis, and atopy, and requires further evaluation by an otolaryngologist.[9][10]

Stridor due to laryngeal obstruction or compression, most commonly caused by epiglottitis, can be misdiagnosed as croup. In a published case, clinicians incorrectly attributed stridor to croup in a 9-month-old infant with a laryngeal mass caused by disseminated Coccidioidomycosis.[11]

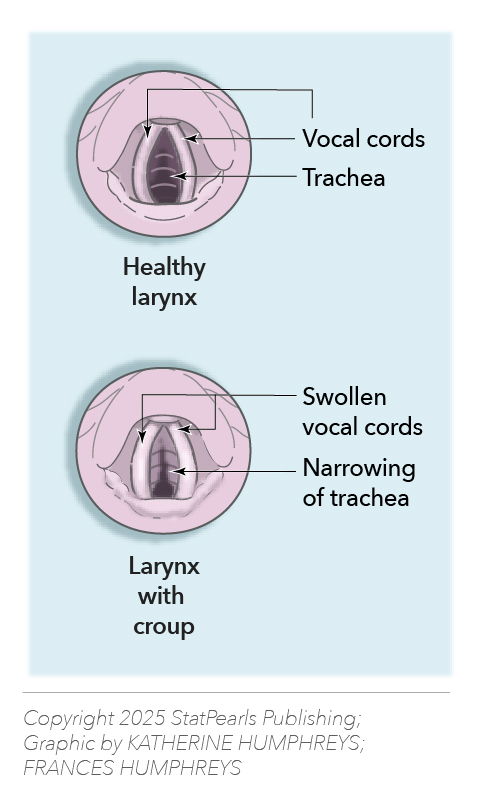

Croup infection starts a cascade of pathophysiological reactions, including the infiltration of white blood cells, edema of the upper airway, partial airway obstruction, increased work of breathing, and turbulent, noisy airflow known as stridor (see Image. Croup: Narrowing of the Upper Airway).

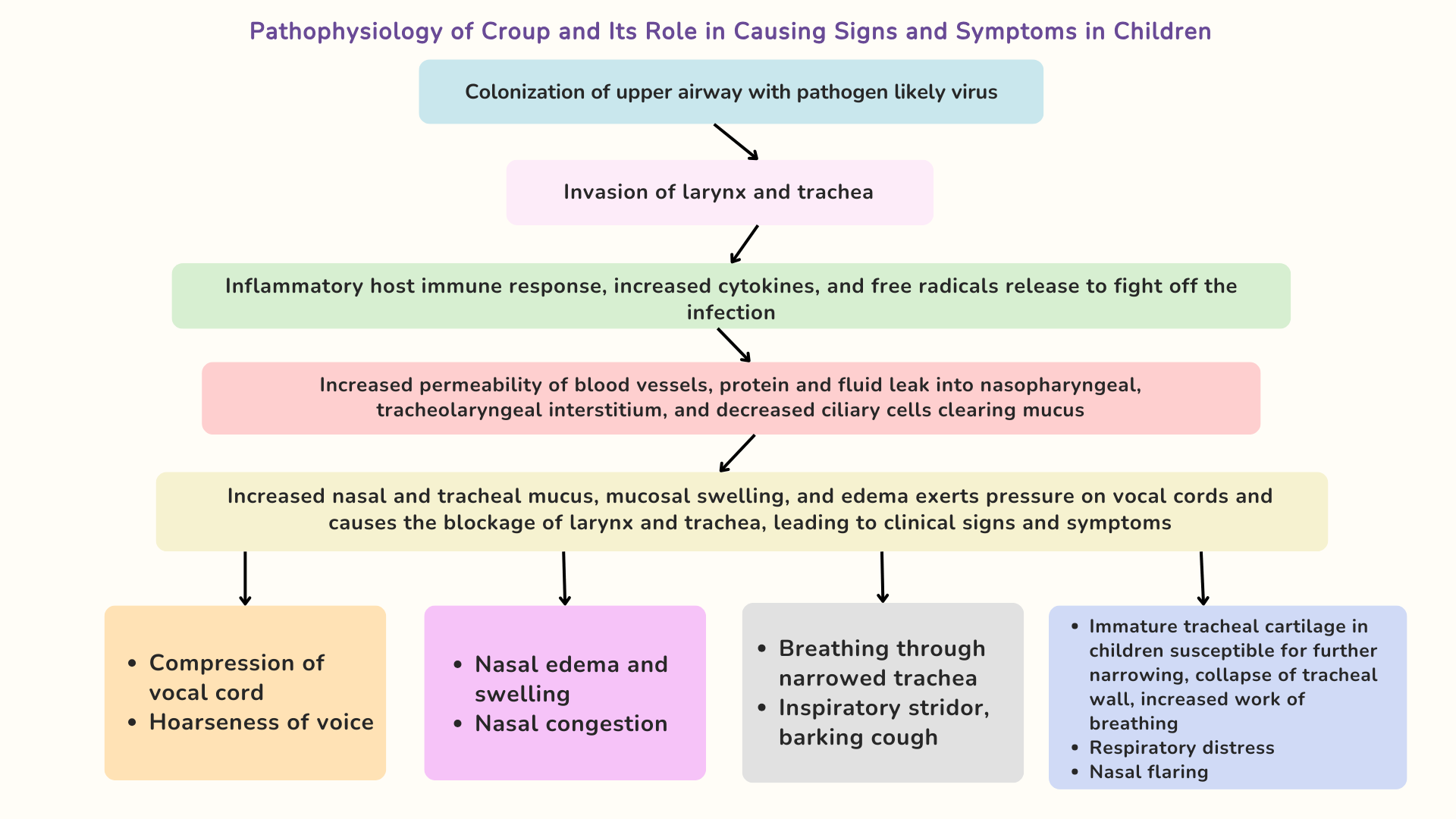

A series of pathophysiological events follows, culminating in the clinical presentation of croup (see Image. Pathophysiology of Croup and Its Role in Causing Signs and Symptoms in Children).[The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease]

History and Physical

The typical presentation of croup is characterized by 1 to 2 days of runny nose, cold symptoms, and low-grade fever, which precede a barking cough, without drooling or dysphagia. The illness lasts typically 3 to 7 days, with the most severe symptoms occurring on days 3 or 4. Croup is characterized by a seal-like barking cough, stridor, hoarseness, and difficulty breathing, which typically worsens at night. Agitation increases the stridor, which can occur at rest. Fever may be absent. Patients may also present with tachypnea and tachycardia. Visual signs such as nasal flaring, retractions, and, in rare cases, cyanosis, increase the suspicion of severe croup. Croup, an upper respiratory condition with stridor, must be differentiated from wheezing associated with lower respiratory conditions such as asthma, pneumonia, or bronchiolitis, rather than croup. Differentiating between stridor and wheezing is crucial, as it directly influences the treatment plan.[12]

Evaluation

The Westley score is the most commonly used system for classifying the severity of croup, ranging from 0 to 17 points, based on 5 factors. The score assesses the severity of croup (see Table. Westley Score for the Classification of Croup).[13]

Table 1. Westley Score for the Classification of Croup

| Signs | Score | |||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Air Entry | Normal | Decreased | Markedly decreased | |||

| Inspiratory Stridor | None | Present during agitation | Present at rest | |||

| Retractions | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Cyanosis | None |

Present when crying |

Present at rest |

|||

| Level of Consciousness | Alert | Disoriented |

Table 2. Westley Score Defining the Severity of Croup

| Westley Score | Severity of Croup |

| ≤2 | Mild |

| 3-5 | Moderate |

| 6-11 | Severe |

| >12 | Impending respiratory failure |

A study involving 192 children with croup was conducted to identify factors that influence the Westley score and its impact on outcomes in the pediatric emergency department. Based on the study results, cyanosis and altered consciousness were not clinically significant, even in patients with severe croup, whereas retraction and air entry were the significant factors predicting clinical outcomes. Patients with an initial Westley score of 1 to 2 were safely discharged home, whereas those with a Westley score greater than 5 required hospitalization for further treatment.[13]

Although croup is primarily a clinical diagnosis, laboratory studies and imaging can guide management in selected cases. Nasopharyngeal swabs for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and parainfluenza serologies may confirm alternative diagnoses and change management. Clinicians must differentiate other obstructive conditions, such as epiglottitis, bacterial tracheitis, inhaled foreign bodies, subglottic stenosis, retropharyngeal abscess, and angioedema. A frontal x-ray of the neck is not routinely performed, but it may demonstrate a steeple sign characteristic of croup due to narrowing of the trachea, which resembles a church steeple. Blood tests and viral cultures are not routinely recommended, as they may cause increased agitation, potentially leading to further airway edema and obstruction. Viral cultures, obtained through nasopharyngeal aspiration, can confirm the etiology but are typically limited to research settings. Bacterial infection is considered a primary or secondary factor if the patient does not respond to standard treatments.[Clarke M, Allaire J. An evidence-based approach to the evaluation and treatment of croup in children. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract 2012; 9:1] Patients with recurrent croup need evaluation by a multidisciplinary team, including an otolaryngologist. A study by Quraishi et al in 2022 recommended some key points for evaluating recurrent croup. They concluded that children younger than 1 or 3 with a history of intubation presenting with recurrent croup should undergo triple endoscopy to identify structural airway abnormalities. If no airway abnormalities exist, patients should be screened for asthma and gastroesophageal reflux disease and treated empirically. The study concluded that the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease and asthma improves the symptoms of recurrent croup.[8]

Treatment / Management

Based on the Westley croup score, treatment depends on the severity of signs and symptoms. Children with mild croup receive a single dose of dexamethasone, symptomatic treatment, and supportive care. Children with moderate-to-severe croup are given nebulized epinephrine and dexamethasone.[14](A1)

All patients with diminished oxygen saturation should receive supplemental oxygen. Moderate-to-severe cases require observation and admission if the symptoms do not improve.[15]

Steroids

- Dexamethasone, a glucocorticosteroid, helps accelerate recovery, lowers the need for additional medical care, and shortens the length of hospital stay.

- Dexamethasone is superior to budesonide for improving symptom scores, but does not appear to reduce readmission rates.

- Dexamethasone doses of 0.15, 0.3, or 0.6 mg/kg appear equally effective; 0.6 mg/kg is the most commonly used dose.[16]

- Oral dexamethasone is the preferred treatment for children with croup because it is effective, widely available, safe, and easily administered. A single dose is sufficient for most children. If symptoms persist for 3 to 4 days after the first dose of dexamethasone, a second dose can be administered.

- The oral route is less invasive than an injection, making it more comfortable for children already experiencing respiratory distress. However, in cases where the child is unable to swallow, is vomiting, or has severe respiratory distress, intramuscular or intravenous dexamethasone may be necessary. Oral medication is also less costly and may be prescribed for home use in cases of mild croup.

- If an intravenous line is already in place, the parenteral route is preferred over intramuscular injections because they cause additional discomfort and distress.[17] (A1)

Epinephrine

- Nebulized racemic epinephrine has been shown to improve symptom scores within 30 minutes, but its effects may diminish after 2 hours in patients with moderate-to-severe croup, who, therefore, require a prolonged period of observation after receiving racemic epinephrine. If symptoms improve, they can be discharged home after 4 hours of observation, with instructions for close follow-up.

- Administering approximately 0.5 mL/kg of L-epinephrine 1:1000 using a nebulizer appears more effective than racemic epinephrine at 2 hours due to its longer duration of action.[18] (A1)

Oxygen: Administration of medications using less invasive techniques is recommended in patients with croup, as any agitation can worsen the symptoms. Therefore, oxygen delivery by blow-by administration may be more effective than using a mask or nasal cannula.[15]

Intubation

- Approximately 0.2% of children require endotracheal intubation for respiratory support. Two retrospective studies found that fewer than 3% of children hospitalized for croup needed intubation.[15]

- Clinicians should use an endotracheal tube 0.5 size smaller than typical for the patient's age and size to account for airway narrowing due to swelling and inflammation.

Hot Steam: Studies have not shown significant improvement with the administration of inhaled hot steam or humidified air. Exposure to cold outdoor night air is more effective in lessening croup symptoms.[19](A1)

Cough Medicine: Guidelines discourage the use of cough medicines, which typically contain dextromethorphan or guaifenesin. These medications can cause drowsiness in a child, requiring increased effort to breathe, which may exacerbate the symptoms of croup.[U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Use Caution When Giving Cough and Cold Products to Kids]

Heliox: Heliox is a mixture of helium and oxygen; however, there is limited evidence to support its routine use. This mixture can decrease the increased work of breathing by reducing turbulent airflow in patients with severe croup. Heliox is an option if respiratory distress persists despite other therapies, and it can serve as a temporary measure to prevent intubation while waiting for steroids to take effect in reducing airway edema.[20](A1)

Antibiotics

- Croup is primarily a viral illness. Antibiotics are considered when a primary or secondary bacterial infection is suspected.

- Secondary bacterial infection should be treated based on the possible causative bacterial agent. Vancomycin and cefotaxime are preferred antibiotics.

- Severe symptoms of croup caused by influenza A or B may respond to antiviral neuraminidase inhibitors.[7] (A1)

Approximately 5% of children treated for croup in the outpatient setting have repeat visits for recurrent symptoms within 7 days. Children with recurrent croup episodes should be referred to an otolaryngologist to evaluate for underlying airway abnormalities, such as laryngomalacia, subglottic stenosis, gastroesophageal reflux disease pathology, or hemangiomas. Airway abnormalities are identified in approximately 10% of children with recurrent croup referred to otolaryngologists and 45% of those who undergo airway endoscopy.[21][22][23](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of croup includes other causes of stridor and respiratory distress, such as bacterial tracheitis, epiglottitis, foreign body aspiration, hemangioma, peritonsillar abscess, neoplasm, retropharyngeal abscess, and smoke inhalation. Rarely, neurological causes can cause stridor that mimics croup. In a report, 3 children presented with stridor and were treated for croup but were eventually found to have a neurological cause of stridor.[24]

Acute Epiglottitis

Acute epiglottitis is rare due to vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae type B. The patient does not have a barking cough but has anxiety out of proportion to the degree of respiratory distress. Symptom onset is generally rapid; the child appears febrile and ill-appearing. Affected children prefer to sit upright in a tripod position, and cough is rare. The thumb sign due to a swollen epiglottis may be noted on a radiograph. A cough is highly sensitive and specific for croup, whereas drooling may indicate bacterial epiglottitis. Other symptoms include acute onset of dysphagia, odynophagia, high fever, and a muffled voice.[12]

Distinguishing croup from epiglottitis is essential because patients with the latter may deteriorate rapidly. If acute epiglottitis is suspected, it is imperative to keep the child calm and avoid asking them to open their mouth wide, as this could precipitate fatal airway obstruction. An emergent ear, nose, and throat (ENT) consultation for airway evaluation in the operating room is essential for suspected epiglottitis. The Haemophilus influenzae vaccine, licensed in 1985, decreased cases of epiglottitis, but with the current rates of vaccine refusals, acute epiglottitis cases are likely to occur. All patients with epiglottitis should be admitted to the intensive care unit for close monitoring.[25]

Bacterial Tracheitis

Bacterial tracheitis is also called bacterial croup. An exudative bacterial infection invades tracheal soft tissue and occurs as a primary infection or secondary to viral croup. In secondary bacterial infection, mild viral croup symptoms worsen, and patients exhibit high fevers, a toxic appearance, and severe respiratory distress. Radiographs may show nonspecific edema and irregularities of the tracheal wall.[26]

Deep Neck Space Abscesses

Patients with peritonsillar, parapharyngeal, or retropharyngeal abscesses typically lack symptoms of croup, such as barking cough and stridor. Children may present with drooling, fever, difficulty swallowing, neck stiffness, enlargement of cervical lymph nodes, and a toxic appearance. With deep neck space abscesses, cellulitis of the cervical prevertebral tissues may occur. Children with a retropharyngeal abscess typically have fever, drooling, dysphagia, and odynophagia but also complain of neck pain with a bulging posterior pharyngeal wall on neck radiography. Children with a peritonsillar abscess often complain of a sore throat, fever, and a classic hot potato voice.[27]

Foreign Body

A previously healthy child presents with a sudden onset of choking and upper airway obstruction symptoms. A foreign body lodged in the larynx causes hoarseness and stridor. A large foreign body in the upper esophagus can pressurize the extra-thoracic trachea, resulting in a barking cough and inspiratory stridor. Late onset of stridor can occur due to the ingestion of a nonobstructive erosive foreign body, such as a button battery.[28]

Allergic Reaction or Acute Angioneurotic Edema

Patients present with a sudden onset of symptoms such as swollen lips and tongue without preceding respiratory symptoms or fever. The associated symptoms include urticarial rash, difficulty swallowing, and inspiratory stridor. Patients may have a history of allergies and a history of similar episodes in the past.[4]

Congenital and Acquired Anomalies

Congenital and acquired anomalies and upper airway injury can cause stridor. Anatomic abnormalities include laryngeal webs, papillomas, laryngomalacia, subglottic stenosis, hemangiomas, bronchogenic cysts, and vocal cord paralysis. Most patients present with stridor as a chronic symptom without other upper respiratory symptoms or fever.[Clarke M, Allaire J. An evidence-based approach to the evaluation and treatment of croup in children. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract 2012; 9:1]

Prognosis

Patients with mild croup have an excellent prognosis. Hospital admission and mortality rates are low and vary significantly between communities. Fewer than 0.5% of intubated children died in a 10-year study of hospitalized children with croup.[7]

Complications

Symptoms of mild croup subside in the majority of children within 2 days. However, a few patients have symptoms that persist for up to 1 week. Moderate-to-severe croup symptoms need treatment with epinephrine in addition to glucocorticoids. Complications such as pneumonia, pulmonary edema, and secondary bacterial infection may occur, leading to tracheitis, requiring antibiotics.[7]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Croup primarily affects children younger than 6, so patient education is mainly directed toward parents or caregivers. Education focuses on recognizing the signs and symptoms of croup, understanding management options, emphasizing the importance of supportive care, and identifying red flags that require medical attention. Parents should be instructed to keep their child calm and comfortable, as agitation or crying can worsen breathing difficulties. Supportive measures at home include using a humidifier to ease airway irritation, encouraging fluid intake and rest, administering fever-reducing medications if needed, and exposing the child to cool, moist air. Parents should also look for warning signs such as difficulty breathing, use of accessory chest or neck muscles to breathe, a high-pitched sound (stridor) at rest, bluish or gray discoloration of the lips or fingertips, trouble swallowing, or symptoms lasting more than 3 to 5 days. The presence of any of these worrisome signs or symptoms warrants immediate medical evaluation at the nearest emergency facility.

Pearls and Other Issues

Croup is generally a mild and self-limited upper respiratory illness, resolving within a few days. Severe illness and complications may occur, which include secondary bacterial infection leading to bacterial tracheitis, pneumonia, pulmonary edema, and, rarely, respiratory failure and death. Annual immunization against the influenza virus and age-appropriate scheduled diphtheria vaccination may reduce the incidence of croup.[7]

Patients with mild croup can be treated at home with supportive care, including antipyretics for fever, adequate fluid intake, and exposure to mist, a humidifier, or cold outdoor air. Caregivers should be instructed on how to provide these measures and monitor warning signs and symptoms such as stridor at rest, increased work of breathing, retractions, difficulty breathing, pallor, cyanosis, and fatigue so that patients can receive timely medical attention. Patients with mild croup who present to the emergency department or outpatient facilities can receive a single dose of oral dexamethasone. Treatment with nebulized epinephrine is not necessary for the management of mild croup.[7]

Patients with moderate croup should be evaluated and monitored. These patients often require the administration of racemic epinephrine in addition to dexamethasone and supportive care. Patients can be discharged if the following criteria are met:

- They are improved 3 hours after the last nebulized racemic epinephrine treatment

- Pulse oximetry reading is normal

- They tolerate oral fluids

- They have a non-toxic appearance, normal color, and no stridor at rest

- They have reliable caretakers who understand symptoms requiring a return visit

- They can return for close follow-up if needed

According to the Westley score, patients with severe croup or those showing persistent symptoms after 2 or more doses of racemic epinephrine should be considered for extended observation or hospital admission.[7]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with croup are often assessed by primary care clinicians or in emergency departments. Educating healthcare providers is essential to ensure they understand that croup is generally a self-limiting condition, with most patients achieving full recovery through supportive care alone and having an excellent prognosis. Many may benefit from pharmacological therapy in the form of a single dose of dexamethasone. A community-based study of children with croup found no difference in symptom scores between 3 daily doses of prednisolone (2 mg/kg) and 1 dose of dexamethasone (0.6 mg/kg).[29]

In another study on pediatric patients with croup, steroids effectively reduced croup symptoms, shortened hospital admission stays, and reduced the need for follow-up visits.[30]

Patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms should receive prompt care, including racemic epinephrine, steroids, oxygen as needed, and supportive management. Recurrent and atypical croup merits special attention to determine the underlying cause and appropriate treatment. Emergency nurses are often the first to evaluate patients and must recognize those who require urgent interventions. A collaborative team of healthcare providers, nurses, and pharmacists must be engaged in ordering, verifying the dosage of medications, checking for drug-drug interactions, administering medications, educating families, and reporting changes for effective closed-loop communication. In severe cases of croup, involvement of other skilled professionals such as ENT specialists, anesthesiologists, intensivists, and operating room staff is critical for securing the patient's airway and providing ongoing care.[30]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bjornson CL, Johnson DW. Croup in children. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2013 Oct 15:185(15):1317-23. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121645. Epub 2013 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 23939212]

Rihkanen H, Rönkkö E, Nieminen T, Komsi KL, Räty R, Saxen H, Ziegler T, Roivainen M, Söderlund-Venermo M, Beng AL, Hovi T, Pitkäranta A. Respiratory viruses in laryngeal croup of young children. The Journal of pediatrics. 2008 May:152(5):661-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.10.043. Epub 2008 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 18410770]

Lee JK, Song SH, Ahn B, Yun KW, Choi EH. Etiology and Epidemiology of Croup before and throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic, 2018-2022, South Korea. Children (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 Oct 9:9(10):. doi: 10.3390/children9101542. Epub 2022 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 36291478]

Cherry JD. Clinical practice. Croup. The New England journal of medicine. 2008 Jan 24:358(4):384-91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp072022. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18216359]

Weinberg GA, Hall CB, Iwane MK, Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Griffin MR, Staat MA, Curns AT, Erdman DD, Szilagyi PG, New Vaccine Surveillance Network. Parainfluenza virus infection of young children: estimates of the population-based burden of hospitalization. The Journal of pediatrics. 2009 May:154(5):694-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.11.034. Epub 2009 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 19159905]

Zoorob R, Sidani M, Murray J. Croup: an overview. American family physician. 2011 May 1:83(9):1067-73 [PubMed PMID: 21534520]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohnson DW. Croup. BMJ clinical evidence. 2014 Sep 29:2014():. pii: 0321. Epub 2014 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 25263284]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceQuraishi H, Lee DJ. Recurrent Croup. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2022 Apr:69(2):319-328. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2021.12.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35337542]

Hanna R, Lee F, Drummond D, Yunker WK. Defining atypical croup: A case report and review of the literature. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2019 Dec:127():109686. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.109686. Epub 2019 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 31542653]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCoughran A, Balakrishnan K, Ma Y, Vaezeafshar R, Capdarest-Arest N, Hamdi O, Sidell DR. The Relationship between Croup and Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Laryngoscope. 2021 Jan:131(1):209-217. doi: 10.1002/lary.28544. Epub 2020 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 32040207]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSah A, Civelli VF, Donath C, Mandviwala L, Heidari A. A 9-Month-Old Boy With "3 Months of Croup" a Devil Inside. Journal of investigative medicine high impact case reports. 2022 Jan-Dec:10():23247096211066392. doi: 10.1177/23247096211066392. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35543558]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTibballs J, Watson T. Symptoms and signs differentiating croup and epiglottitis. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2011 Mar:47(3):77-82. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01892.x. Epub 2010 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 21091577]

Yang WC, Lee J, Chen CY, Chang YJ, Wu HP. Westley score and clinical factors in predicting the outcome of croup in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatric pulmonology. 2017 Oct:52(10):1329-1334. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23738. Epub 2017 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 28556543]

Bjornson CL, Klassen TP, Williamson J, Brant R, Mitton C, Plint A, Bulloch B, Evered L, Johnson DW, Pediatric Emergency Research Canada Network. A randomized trial of a single dose of oral dexamethasone for mild croup. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 Sep 23:351(13):1306-13 [PubMed PMID: 15385657]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSmith DK, McDermott AJ, Sullivan JF. Croup: Diagnosis and Management. American family physician. 2018 May 1:97(9):575-580 [PubMed PMID: 29763253]

Aregbesola A, Tam CM, Kothari A, Le ML, Ragheb M, Klassen TP. Glucocorticoids for croup in children. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2023 Jan 10:1(1):CD001955. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001955.pub5. Epub 2023 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 36626194]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDonaldson D, Poleski D, Knipple E, Filips K, Reetz L, Pascual RG, Jackson RE. Intramuscular versus oral dexamethasone for the treatment of moderate-to-severe croup: a randomized, double-blind trial. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003 Jan:10(1):16-21 [PubMed PMID: 12511310]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEghbali A, Sabbagh A, Bagheri B, Taherahmadi H, Kahbazi M. Efficacy of nebulized L-epinephrine for treatment of croup: a randomized, double-blind study. Fundamental & clinical pharmacology. 2016 Feb:30(1):70-5. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12158. Epub 2015 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 26463007]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSiebert JN, Salomon C, Taddeo I, Gervaix A, Combescure C, Lacroix L. Outdoor Cold Air Versus Room Temperature Exposure for Croup Symptoms: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics. 2023 Sep 1:152(3):. pii: e2023061365. doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-061365. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37525974]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMoraa I, Sturman N, McGuire TM, van Driel ML. Heliox for croup in children. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2021 Aug 16:8(8):CD006822. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006822.pub6. Epub 2021 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 34397099]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCooper T, Kuruvilla G, Persad R, El-Hakim H. Atypical croup: association with airway lesions, atopy, and esophagitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2012 Aug:147(2):209-14. doi: 10.1177/0194599812447758. Epub 2012 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 22588730]

Hodnett BL, Simons JP, Riera KM, Mehta DK, Maguire RC. Objective endoscopic findings in patients with recurrent croup: 10-year retrospective analysis. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2015 Dec:79(12):2343-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.10.039. Epub 2015 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 26574171]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRankin I, Wang SM, Waters A, Clement WA, Kubba H. The management of recurrent croup in children. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2013 May:127(5):494-500. doi: 10.1017/S0022215113000418. Epub 2013 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 23544702]

Gerard R, Nolent P, Lerouge-Bailhache M, Sagardoy T, Dienst T. When Stridor is Not Croup: A Case Report. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2022 Nov:63(5):673-677. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2022.09.010. Epub 2022 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 36369121]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDowdy RAE, Cornelius BW. Medical Management of Epiglottitis. Anesthesia progress. 2020 Jun 1:67(2):90-97. doi: 10.2344/anpr-66-04-08. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32633776]

Burton LV, Lofgren DH, Silberman M. Bacterial Tracheitis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262085]

Esposito S, De Guido C, Pappalardo M, Laudisio S, Meccariello G, Capoferri G, Rahman S, Vicini C, Principi N. Retropharyngeal, Parapharyngeal and Peritonsillar Abscesses. Children (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 Apr 26:9(5):. doi: 10.3390/children9050618. Epub 2022 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 35626793]

Passali D, Gregori D, Lorenzoni G, Cocca S, Loglisci M, Passali FM, Bellussi L. Foreign body injuries in children: a review. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2015 Oct:35(4):265-71 [PubMed PMID: 26824213]

Garbutt JM, Conlon B, Sterkel R, Baty J, Schechtman KB, Mandrell K, Leege E, Gentry S, Stunk RC. The comparative effectiveness of prednisolone and dexamethasone for children with croup: a community-based randomized trial. Clinical pediatrics. 2013 Nov:52(11):1014-21. doi: 10.1177/0009922813504823. Epub 2013 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 24092872]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGates A, Gates M, Vandermeer B, Johnson C, Hartling L, Johnson DW, Klassen TP. Glucocorticoids for croup in children. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Aug 22:8(8):CD001955. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001955.pub4. Epub 2018 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 30133690]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence