Introduction

In the United States, colorectal cancer represents the third most frequently diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality.[1] Colonoscopy is recognized as the gold standard modality for colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis, and it also serves as a therapeutic intervention through polypectomy of lesions with malignant potential. This procedure facilitates the diagnosis of numerous nonmalignant colorectal conditions, including ulcerative colitis, diverticular disease, and lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage.[2] Colonoscopy uses a flexible, hand-held endoscope equipped with a high-definition camera positioned at the instrument tip, accompanied by accessory channels enabling insufflation, irrigation, suction, and insertion of additional equipment.

Visual data transmitted from the camera to the display monitor facilitates detection of colorectal mucosal abnormalities and enables appropriate interventions, including tissue biopsy, polypectomy, stricture dilatation, and hemostasis of bleeding lesions. Colonoscopy demonstrates superior diagnostic sensitivity and specificity compared to alternative modalities such as barium enema, fecal occult blood testing, and computed tomography colonography. Therefore, despite the substantial learning curve required for technical proficiency, colonoscopy remains widely accepted as the gold standard for screening and diagnosing various colorectal pathologies, particularly malignancies.[3]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

A comprehensive understanding of endoscopic anatomy, including recommendations, performance, complication monitoring, and result interpretation, is essential for healthcare professionals in colonoscopy procedures. Colonoscopic examination commences with perianal skin and anal verge inspection to exclude contraindications such as acute anal fissures, intersphincteric and perianal abscesses, or thrombosed external hemorrhoids that may preclude the procedure.

The anal canal measures 3 to 4 cm in length, extending to the squamocolumnar junction, also termed the dentate line. Most anal pathologies require proctoscopic evaluation rather than colonoscopic assessment for accurate diagnosis. The rectum extends 15 cm from the squamocolumnar junction to the sigmoid colon. Colonoscopically, the rectum demonstrates a capacious ampulla containing 3 or more semilunar folds termed the valves of Houston. These semilunar structures may create visualization blind spots during examination; therefore, thorough inspection utilizing scope retroflexion when feasible is recommended. The rectosigmoid junction represents the narrowest portion of the large intestine, characterized by an acute angulation requiring technical expertise for navigation.[4]

The sigmoid colon measures 40 to 70 cm in length, with variation dependent upon the insufflation volume utilized. Consequently, anatomic localization of sigmoid pathology based solely on colonoscopic findings may lack precision. Sigmoid navigation may present technical challenges in patients with prior abdominal surgical procedures, causing adhesions, previous pelvic inflammatory conditions, including abscesses, or redundant sigmoid anatomy, resulting in excessive looping and procedural discomfort.[4]

The descending colon maintains retroperitoneal fixation and typically permits straightforward scope advancement until the splenic flexure, where acute angulation occurs. Transverse colon entry is identified by triangular mucosal folds attributed to the relatively thin circular muscularis propria layer compared to the longitudinal taeniae muscles. The hepatic flexure demonstrates a gray-blue hepatic impression, followed by anterior angulation toward the ascending colon. Like the descending colon, the ascending colon maintains a retroperitoneal position with a straight configuration leading to the cecum.

Upon cecal intubation, the 3 taeniae coli converge around the appendiceal orifice, creating the tri-radiate fold known as the "Mercedes-Benz sign." The appendiceal orifice and ileocecal valve serve as reliable landmarks for the cecum. The ileocecal valve contains superior and inferior lips leading to the terminal ileum.[5] The terminal ileum exhibits bile-tinged mucosa that appears granular under air insufflation, with visible floating villi under water immersion.[6]

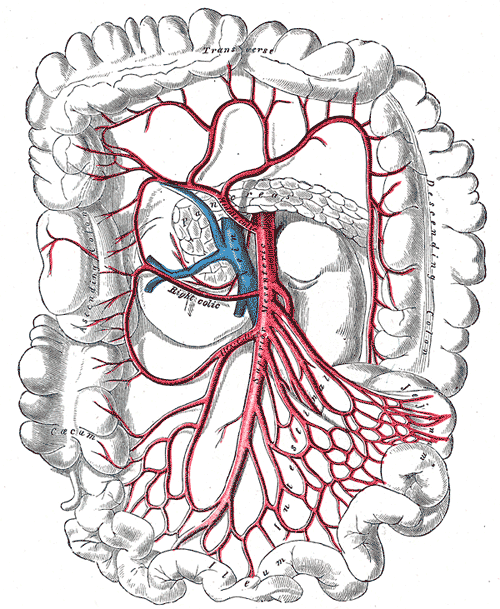

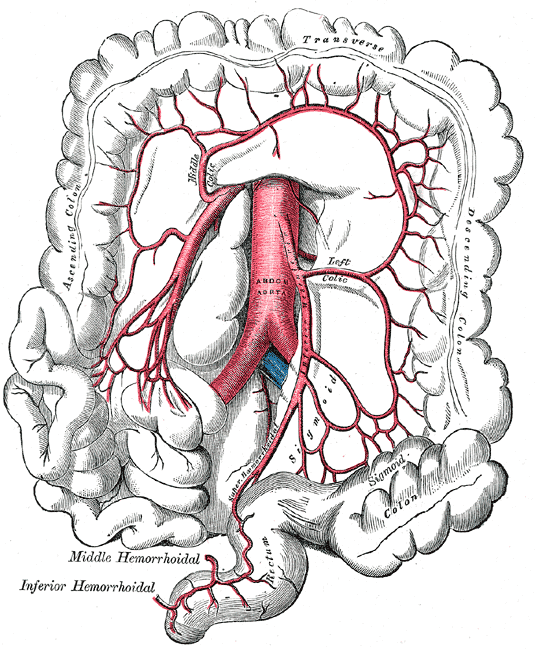

Colonic vascular supply derives from 2 primary vessels: the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) (see Images. Superior Mesenteric Artery Anatomy; and Superior and Inferior Mesenteric Arteries). The SMA supplies the small intestine, cecum, ascending colon, and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon. The IMA supplies the distal transverse colon, the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, and the proximal rectum. Vascular anatomic knowledge remains crucial for colorectal resection procedures.[7]

Indications

Colonoscopy indications are classified into diagnostic and therapeutic categories. Diagnostic indications encompass colorectal cancer screening and elective evaluation of patients presenting with lower gastrointestinal symptoms. Screening colonoscopy is performed to assess for colorectal malignancies and premalignant conditions, including polyps, based on individual risk stratification. The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends colonoscopy every 10 years for patients aged between 50 and 75 years at average risk for colorectal cancer (grade A recommendation). Moderate benefit exists for screening individuals aged 45 to 49, with a small net benefit for those aged 76 to 85. Patients aged older than 85 with a life expectancy of less than 10 years and the absence of alarming symptoms do not warrant a screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer detection.[8][9]

Patients at elevated risk for colorectal cancer development require colonoscopy at a younger age than 50, with surveillance intervals of 1, 2, or 5 years based on primary risk factors and procedural findings. High-risk populations include:

• Familial adenomatous polyposis• Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (Lynch syndrome)• Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome• Ulcerative colitis• Significant family history of colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, gastric, biliary, and urothelial malignancies

Patients with a history of prior colorectal resections for malignant conditions require surveillance colonoscopies at 1, 3, and 5-year intervals, followed by routine screening colonoscopies. Individuals with first-degree relatives diagnosed with colon cancer should undergo colonoscopy at age 40 years or 10 years before the relative's age at diagnosis, whichever occurs first.[10][11] Elective colonoscopy is indicated for patients presenting with unexplained weight loss, rectal bleeding, altered bowel habits, abdominal pain associated with constipation or diarrhea, positive fecal occult blood testing, iron deficiency anemia, and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, obstructive or dyssynergic defecation syndrome.

Patients with suspected inflammatory or infectious colitis, diverticular disease, genitourinary-large bowel fistulae, irritable bowel syndrome, and colorectal pathologies identified on imaging studies require colonoscopic evaluation. Patients scheduled for rectal prolapse repair, anal sphincter reconstruction, and complex fistula-in-ano procedures should undergo colonoscopy to exclude concurrent colorectal pathology.[12] Therapeutic colonoscopy indications include hemostasis, lesion excision and ablation, stricture or stenosis dilation and stenting, colonic volvulus or megacolon decompression, and palliation of bleeding in recurrent or inoperable colorectal malignancies. Therapeutic colonoscopy has substantially replaced or reduced the necessity for conventional surgical interventions.[13]

Contraindications

While colonoscopy is a critical diagnostic and therapeutic modality for various colorectal pathologies, specific contraindications require careful consideration. A quality colonoscopic examination requires adequate bowel preparation. Patients who are medically unsuitable or unable to tolerate bowel preparation represent relative contraindications. These circumstances include recent myocardial infarction, acute renal failure, decompensated hepatic disease, coagulopathies and bleeding disorders, hemodynamic instability, peritonitis, and recent surgical procedures involving colorectal anastomoses. Absolute contraindications encompass complete large bowel obstruction secondary to malignant neoplasms or strictures, fulminant colitis, acute diverticulitis, diverticular perforation with abscess formation, and active inflammatory bowel disease with elevated risk of mucosal injury and perforation during colonoscopic examination.[14]

Clinicians must recognize scenarios where colonoscopy is not indicated. These conditions include surveillance of inflammatory or hyperplastic polyps, routine follow-up of inflammatory bowel disease in patients maintaining clinical remission, metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin without lower gastrointestinal symptoms, patients with diarrhea of less than four weeks' duration, uncomplicated constipation without high-risk features, and uncomplicated abdominal pain. Although colonoscopic evaluation in these circumstances remains at the clinician's discretion, there are no absolute indications. Therefore, procedural benefits must be carefully weighed against potential complications before proceeding.[15]

Equipment

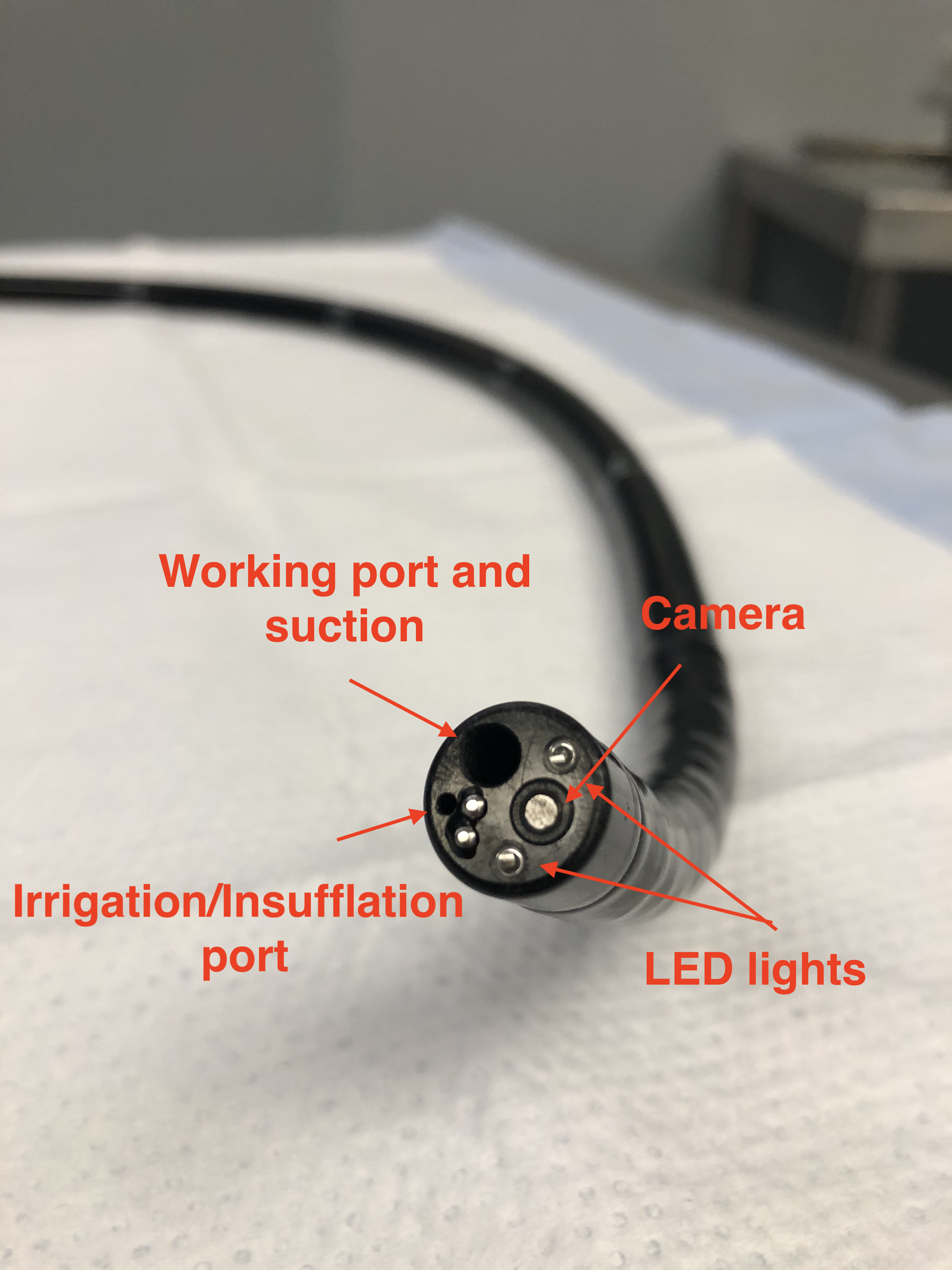

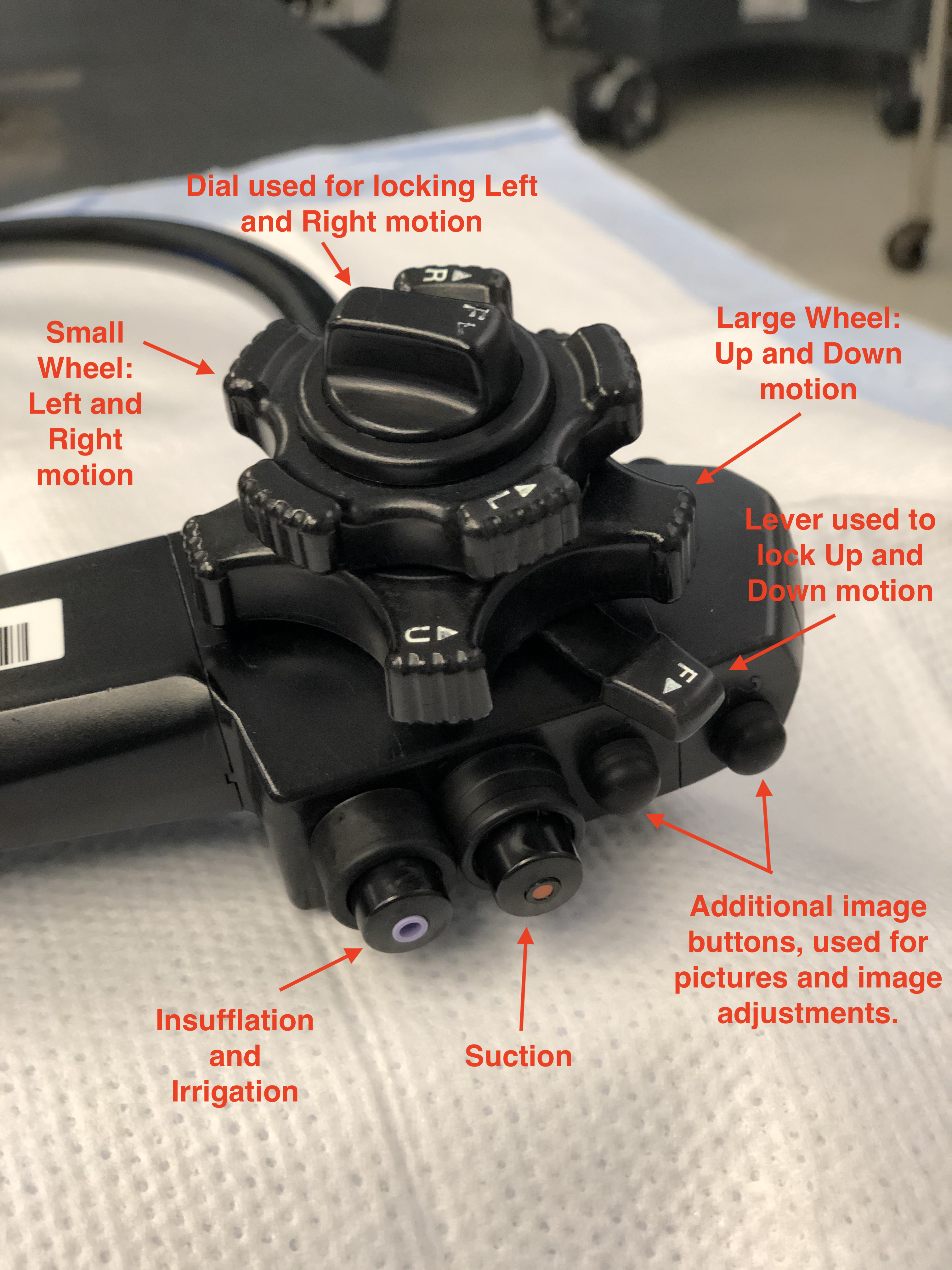

Colonoscopy equipment comprises 2 primary components: the central processing unit and the colonoscope (see Images. Standard Colonoscope; Colonoscope, Parts and Definitions; and Colonoscope, Components Description). The colonoscope is a flexible, cylindrical tube designed for single-operator manipulation. Both pediatric and adult-sized endoscopes are available. Depending on the manufacturer's specifications and scope dimensions, the scope measures approximately 160 to 180 cm long, with a 1.0 to 1.2 cm diameter. The colonoscope tip contains several essential working components, including a high-definition camera for transmitting images to the monitor, 2 light-emitting diodes that provide adequate colonic mucosal illumination, and channels that facilitate insufflation, irrigation, suction, and instrument passage.[4]

The colonoscope features a handle designed for left-hand operation, while the right hand manipulates and advances or withdraws the scope at the anal insertion point. Dials at the handle base permit scope rigidity adjustment, enabling navigation through challenging anatomical corners and applying variable tension during colonoscope advancement and withdrawal. The handle incorporates multiple manipulating devices, buttons for insufflation, suction, irrigation functions, and ports for instrument passage, including biopsy forceps, snares, clip appliers, and polypectomy devices. Additional working instruments attached to the handle facilitate image quality adjustment and videography control options during colonoscopic examination, including recording, freeze frame, image capture, and magnification functions.

Two notable controls on the scope handle are the adjustment wheels located to the right of the handle. The larger wheel enables upward and downward scope movement, while the smaller wheel facilitates left and right directional adjustments. These controls, combined with the colonoscope's rotational capability, provide a wide range of motion and movement for optimal colonic visualization.[4] A colonoscopy suite requires additional equipment, including a high-definition monitor, an insufflation device generating positive pressure within the intestinal lumen, a suction apparatus, various grasping instruments, and irrigation equipment.[4]

Personnel

For a safe colonoscopy, it is essential to have appropriate personnel, which consists of the endoscopist, a nurse to administer medications, assist in position change, and provide abdominal counter pressure when required, and a technician who can assist with the equipment setup, patient positioning, and troubleshooting. The 2-person method allows an extra pair of hands to guide the scope. Still, it has a higher chance of perforation since the colonoscopist only manipulates the control section, and an assistant maneuvers the scope. In the 1-person technique, the most common method, the colonoscopist can be standing or seated, depending on one’s preference.[4]

Having an experienced assistant has improved patient satisfaction and increased the chances of detecting pathologies.[16] Colonoscopy can be performed without an anesthesiologist or certified registered nurse anesthesiologist (CRNA). However, this requires the colonoscopist to be familiar with sedation medications and contraindications, and their attention to be divided between the procedure and the patient's comfort and sedation status. To better assist with the patients' satisfaction, an anesthesiologist or CRNA can be of assistance to help provide deep sedation, especially in patients who are obese, have tortuous colons or anatomic variations, previous abdominal operations, and pathologies such as diverticulosis and inflammatory bowel disease.[17]

Preparation

An effective and complete colonoscopy requires appropriate bowel preparation. Suboptimal bowel preparation may result in missed flat and serrated lesions and early colorectal malignancies.[18] Inadequate bowel preparation increases the risk of perforation and false-negative results. Multiple studies' results demonstrate significantly improved patient outcomes and enhanced early detection of colorectal cancer with optimal bowel preparation.[19][20] This factor, combined with cecal intubation time, ileocecal intubation rate, and withdrawal time, is a colonoscopy quality indicator.[17]

Ideal bowel preparation includes removing residual stool from the colon without inducing mucosal abnormalities or electrolyte imbalances, while maintaining palatability, tolerability, and safety. Available bowel preparation agents vary in their mechanism of action and volume requirements. Generally, patient compliance improves with reduced preparation volumes; therefore, split-dosing regimens are recommended, with at least 1 dose administered on the colonoscopy day. [20][21]

Various bowel preparation regimens exist, including polyethylene glycol agents that are isotonic and function by retaining fluid within the colonic and small intestinal lumens. In contrast, hypertonic agents, such as sodium phosphate, induce fluid shifts toward the colonic and small bowel lumens. Common adverse effects of bowel preparation agents include nausea, abdominal fullness, pain, bloating, vomiting, dizziness, dehydration, and fatigue. These effects must be explained to patients before administration, with particular caution in patients with cardiac failure, hepatic disease, and renal disease.[20]

Antibiotic prophylaxis for colonoscopy remains a topic of considerable debate. Most guidelines do not recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing diagnostic or therapeutic colonoscopy procedures. High-risk individuals, including those receiving peritoneal dialysis, immunocompromised individuals, patients with active colitis, fulminant colitis, and obstructing malignant lesions requiring stenting, may warrant consideration for antibiotic prophylaxis.[22]

Technique or Treatment

Colonoscopy requires technical proficiency, necessitating simulator practice and proctored procedures to develop clinician competency. Operators must demonstrate familiarity with colonoscope components and functionality. Patient positioning is left lateral decubitus, though some clinicians prefer supine positioning with flexed knees. Positional adjustments may be necessary when manipulating the scope, which becomes challenging. Before scope insertion, the endoscopist must perform a digital rectal examination with water-soluble lubricant to exclude anal and perianal pathology that may preclude or complicate colonoscopic examination.[4] Scope tip movements include vertical and lateral deflections, techniques for endoscopic procedures controlled via handle dials.

Additional techniques encompass:

- Push-forward and pull-back maneuvers: Forward advancement progresses the scope, while pull-back techniques reduce colonic looping and maintain scope straightening and shortening.

- Torque: This is achieved by rotating the scope body in clockwise and counterclockwise directions to negotiate colonic curvatures.

- Air insufflation and suction: These techniques facilitate colonic distension and clearance of secretions for improved visualization. Excessive insufflation may increase colonic tortuosity, complicating the procedure.

- Hooking technique: This involves hooking the scope tip over colonic mucosal folds, followed by pullback maneuvers to straighten tortuous colonic segments.

- Slide-by technique: This entails advancing the scope along the colonic wall when luminal visualization is obscured by angulation or mucosal folds. This technique requires caution due to the risk of iatrogenic perforation from mucosal pressure.

- Jiggling and shaking: This includes moving the scope in 5 to 10 cm increments while maintaining luminal visualization, facilitating colonic shortening, straightening, and advancement.[4]

Important colonoscopic landmarks include:

- Rectal mucosal folds, also known as the valves of Houston, represent the first landmark.

- The rectosigmoid junction presents a challenging intubation area characterized by left-sided angulation that requires torque application with scope advancement.

- The sigmoid colon contains mucosal folds that obscure luminal visualization.

- Sigmoid negotiation, without loop formation and entry into the descending colon, often represents the most demanding step.

- Patient repositioning, abdominal pressure, right-sided torque, minimal insufflation, and jiggling techniques prove beneficial.[23]

The descending colon appears as a straight tube with haustra and fluid levels. The splenic flexure demonstrates a splenic impression, though this is less prominent than the appearance of the hepatic flexure. This represents the highest colonic section located beneath the diaphragm. Flexure negotiation may require supine positioning, with inspiratory breath-holding potentially widening the flexure angle. The transverse colon exhibits triangular mucosal folds with mobility, necessitating minimal insufflation and suctioning for the scope to advance. Umbilical abdominal pressure prevents scope looping in this segment. The hepatic flexure exhibits a gray-blue hepatic impression with luminal redirection toward the ascending colon, necessitating torque and air suction navigation.

The ascending colon presents a triangular luminal configuration, characterized by thicker mucosal folds. Retroperitoneal fixation restricts mobility and facilitates the advancement of the scope. Cecal identification characteristics include the appendiceal orifice, ileocecal valve, and taeniae coli convergence forming the "Mercedes-Benz sign" at cecal termination. The ileocecal valve typically remains closed and requires air suction with the scope tip positioned near the opening for entry. Ileal mucosa demonstrates villi and a bile-tinged appearance.

The United States Multisociety Task Force on Colorectal Cancer establishes 90% cecal intubation targets for routine colonoscopy and 95% for cancer screening procedures.[24] Clinical practice demonstrates success rates of 80-97%. Beyond endoscopist skills and experience, multiple factors contribute to procedural difficulty, including colonic loops or angulation as patient-related variables. The sigmoid colon is the most common site for loop formation, followed by the transverse colon, which can result in endoscope control loss due to increased resistance and patient discomfort. Previously described maneuvers prevent or minimize the formation of loops.[25]

Endoscopists must recognize tension or advancement difficulty. Scope progression should never occur without clear visualization and luminal identification, as this increases the risk of perforation. Loop removal requires the application of suction and scope withdrawal with clockwise shaft rotation, enabling loop elimination and subsequent advancement. Occasionally, scope withdrawal facilitates forward progression.[26]

Inflammatory bowel disease and diverticular disease increase procedural difficulty due to colonic spasticity and inflammation, complicating luminal identification. Poor bowel preparation contributes to procedural challenges and increased rates of missed pathology. Extreme patient body mass indices create procedural difficulties. Previous abdominal surgical procedures may cause interloop adhesions, complicating angle negotiation.[25] Studies demonstrate increased colonoscopic difficulty in female patients due to longer colonic length and increased angulations.[27]

Withdrawal time represents the interval from cecal or terminal ileal intubation until scope removal from the anal canal, excluding additional procedures such as biopsies or polypectomy. This constitutes an important colonoscopic quality indicator, with 9-minute minimum requirements established to improve adenoma detection rates and ensure thorough examination.[28] During colonic withdrawal, air suctioning is required for optimal patient recovery, reducing flatulence, distension, and discomfort. Colonoscopic conclusion includes rectal retroflexion performed by 360-degree scope bending to identify anorectal pathologies, including adenomas, malignancies, and hemorrhoids. Although beneficial, forceful rectal retroflexion may cause perforation; therefore, this maneuver requires careful execution with full rectal inflation to minimize the risk.[29]

Complications

Although colonoscopy is invasive, it is performed under conscious sedation or in awake patients since this procedure is well tolerated without significant risk of adverse outcomes. Complication rates range from 2.8 to 5 per 1000 colonoscopies in screening populations and are higher after therapeutic procedures, such as polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR).[30] To deliver safe and quality outcomes, endoscopists and healthcare professionals must understand potential procedural complications.

General Complications

Cardiopulmonary events represent the most common colonoscopic complications, accounting for over 60%. These range from transient hypotension, hypoxia, and vasovagal syncope to more serious conditions like acute respiratory distress, cardiac arrhythmias, and acute coronary events.[31] Complications secondary to sedative agents include drowsiness, paradoxical restlessness or agitation, hypotension, respiratory depression, and aspiration. Preprocedural patient assessment is crucial for anticipating and preventing these complications. Patients with advancing age and American Society of Anesthesiologists grade 3 or above are more prone to these complications.[32]

Perforation

Iatrogenic perforation represents the most serious colonoscopic complication, leading to severe morbidity. Colonic perforation can result from shearing stress from mechanical endoscope force, barotrauma due to overinsufflation, or direct injury during polypectomy or EMR. The reported incidence ranges from 0.03% to 0.8% for screening and diagnostic colonoscopies, with a twofold increased risk during polypectomies.[33][34] The most common perforation sites are the sigmoid colon and rectosigmoid junction, followed by the cecum. Patients with increased perforation risk include those with diverticular disease, adhesions, and inflammatory bowel disease.[35]

Recognizing colonic perforation is crucial, but it depends on the degree of injury and the patient's condition. Early symptoms include abdominal pain and distention. Late symptoms include hemodynamic instability, dyspnea, abdominal guarding and rigidity, and features of systemic inflammatory response syndrome. While intraperitoneal perforations typically present early with symptoms of peritonitis and sepsis, extraperitoneal perforations can exhibit atypical presentations, such as subcutaneous emphysema, chest pain, and dyspnea.[36]

Early recognition is crucial in determining patient outcomes, as early endoscopic or surgical interventions minimize peritoneal contamination.[37] Patients who do not demonstrate definite peritonitis signs but have suspected perforation should undergo contrast computed tomography, preferably with water-soluble oral contrast agents. Perforation management involves endoscopic closure of defects up to 20 mm, which has a clinical success rate up to 93%. Laparotomy indications include large perforations, failed endoscopic treatment, patients with fecal peritonitis, and tension pneumoperitoneum.[38]

Postpolypectomy Syndrome

Postpolypectomy or postpolypectomy electrocoagulation syndrome results from thermal injury to the colonic wall during polypectomy using electrocoagulation devices and has an incidence of 3 to 4/10,000 colonoscopies. Patients can present with fever, localized abdominal pain, and leukocytosis. Management is often conservative, using broad-spectrum antibiotics, bowel rest, supportive therapy, and close monitoring.[39]

Bleeding

The bleeding risk associated with diagnostic colonoscopies, including mucosal biopsies, is 2.4 to 2.6/1000, with higher rates observed following polypectomy (9.8/1000). Risk factors include patients with cardiovascular and renal diseases, polyps larger than 10 mm, pedunculated polyps, polyps with thick stalks, the depth of submucosal resection, and the use of antiplatelet agents.[40] Intraprocedural bleeding can be managed by endoscopic coagulation, whereas post-procedural and delayed bleeding are often managed conservatively and sometimes require endoscopic therapy.[41]

Splenic Injury

This represents a rare but potentially fatal colonoscopic complication, either due to direct splenic trauma or capsule rupture due to traction, with mortality up to 4.5%.[42] Risk factors include previous abdominal surgeries, splenomegaly, anticoagulant use, endometriosis, and inflammatory colonic conditions. Patients develop left upper quadrant abdominal pain, referred to the left shoulder, and can produce hypotension and shock. Management depends on the patient's condition and can range from expectant treatment with intravenous fluids and blood transfusions, splenic artery embolization, and laparotomy with splenectomy.[43]

Clinical Significance

In the United States (US), colorectal cancer represents the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths, with constant incidence increases and proportionate rises in young individuals and advanced stages.[1] Colonoscopy serves as the gold standard test for colorectal cancer screening and early diagnosis. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for all asymptomatic adults beginning at 45.[8] Colonoscopy can significantly reduce colorectal cancer burden through prevention, early detection, and treatment.[44]

Beyond colonoscopy applications for screening and cancer detection, clinicians should be familiar with other uses, including diagnosis and surveillance of inflammatory bowel and diverticular diseases, and evaluating patients with altered bowel habits, hematochezia, weight loss, abdominal pain, and anemia. Therapeutically, colonoscopy has wide applications including polypectomy, stricture and malignant lesion dilatation and stenting, lower gastrointestinal bleeding electrocoagulation, and sigmoid volvulus reduction.[45]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

With increased colorectal cancer incidence, there has been a steady increase in colonoscopies for screening and surveillance. Quality colonoscopies reduce adenoma miss rates and interval colorectal cancers while enhancing patient satisfaction.[46] Commonly used quality colonoscopy indicators, such as cecal intubation rate, adenoma detection rate, withdrawal time, and complication rate, do not correlate with colonoscopy care quality.[47] Nurses play a significant role as primary caregivers during colonoscopy. Experienced nurse involvement during colonoscopy has been shown to improve polyp and adenoma detection.[48]

All interprofessional healthcare team members should be familiar with the indications, preparation, procedural aspects, and potential complications of colonoscopies. This enhances compliance with colorectal cancer screening recommendations. Primary care clinicians must routinely follow up with patients with symptoms requiring a colonoscopy beyond routine surveillance. Pharmacists must correctly explain bowel preparation regimens, typical side effects, and alarming symptoms.[49]

Interprofessional communication and information sharing are crucial and have been shown to improve colonoscopy outcomes.[50] Nurses and technicians play a significant role in infection control strategies by employing appropriate scope cleaning and disinfection, providing pre-examination patient care and education, monitoring postexamination patients, and educating them regarding expected outcomes, potential adverse effects, and potential complications.[51]

Care coordination is crucial to ensuring efficient and satisfactory patient outcomes. Clinicians, nurses, colonoscopy technicians, and endoscopists must work together to streamline the patient journey through the recommendation, procedure, and follow-up stages. These efforts minimize complications and ensure patient safety, ultimately leading to patient-centered care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Superior Mesenteric Artery Anatomy. This image shows the transverse and descending colon, and the caecum and ileum.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Superior and Inferior Mesenteric Arteries. This image shows the anatomic relationships between the abdominal aorta; ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colonic segments; rectum, right, left, and middle colic arteries; superior and inferior mesenteric arteries; and superior, middle, and inferior hemorrhoidal arteries.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2023 May-Jun:73(3):233-254. doi: 10.3322/caac.21772. Epub 2023 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 36856579]

Berkowitz I, Kaplan M. Indications for colonoscopy. An analysis based on indications and diagnostic yield. South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 1993 Apr:83(4):245-8 [PubMed PMID: 8316919]

Jayasinghe M, Prathiraja O, Caldera D, Jena R, Coffie-Pierre JA, Silva MS, Siddiqui OS. Colon Cancer Screening Methods: 2023 Update. Cureus. 2023 Apr:15(4):e37509. doi: 10.7759/cureus.37509. Epub 2023 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 37193451]

Lee SH, Park YK, Lee DJ, Kim KM. Colonoscopy procedural skills and training for new beginners. World journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Dec 7:20(45):16984-95. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.16984. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25493011]

Finlayson A, Chandra R, Hastie IA, Jones IT, Shedda S, Hong MK, Yen A, Hayes IP. Triradiate caecal fold: Is it a useful landmark for caecal intubation in colonoscopy? World journal of gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2015 Sep 25:7(13):1103-6. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i13.1103. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26421107]

Omole AE, Mandiga P, Kahai P, Lobo S. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Large Intestine. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261962]

Sakorafas GH, Zouros E, Peros G. Applied vascular anatomy of the colon and rectum: clinical implications for the surgical oncologist. Surgical oncology. 2006 Dec:15(4):243-55 [PubMed PMID: 17531744]

US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM, Donahue KE, Doubeni CA, Krist AH, Kubik M, Li L, Ogedegbe G, Owens DK, Pbert L, Silverstein M, Stevermer J, Tseng CW, Wong JB. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021 May 18:325(19):1965-1977. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.6238. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34003218]

Li D. Recent advances in colorectal cancer screening. Chronic diseases and translational medicine. 2018 Sep:4(3):139-147. doi: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2018.08.004. Epub 2018 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 30276360]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLewandowska A, Rudzki G, Lewandowski T, Stryjkowska-Góra A, Rudzki S. Risk Factors for the Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer control : journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2022 Jan-Dec:29():10732748211056692. doi: 10.1177/10732748211056692. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35000418]

Tanadi C, Tandarto K, Stella MM, Sutanto KW, Steffanus M, Tenggara R, Bestari MB. Colorectal cancer screening guidelines for average-risk and high-risk individuals: A systematic review. Romanian journal of internal medicine = Revue roumaine de medecine interne. 2024 Jun 1:62(2):101-123. doi: 10.2478/rjim-2023-0038. Epub 2023 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 38153878]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCai J, Yuan Z, Zhang S. Abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation--which symptom is more indispensable to have a colonoscopy? International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2015:8(1):938-42 [PubMed PMID: 25755799]

Forde KA. Therapeutic colonoscopy. World journal of surgery. 1992 Nov-Dec:16(6):1048-53 [PubMed PMID: 1455873]

Jechart G, Messmann H. Indications and techniques for lower intestinal endoscopy. Best practice & research. Clinical gastroenterology. 2008:22(5):777-88. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2008.06.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18790432]

Telford JJ. Inappropriate uses of colonoscopy. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2012 May:8(5):342-4 [PubMed PMID: 22933868]

Fu L, Dai M, Liu J, Shi H, Pan J, Lan Y, Shen M, Shao X, Ye B. Study on the influence of assistant experience on the quality of colonoscopy: A pilot single-center study. Medicine. 2019 Nov:98(45):e17747. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017747. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31702625]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTinmouth J, Kennedy EB, Baron D, Burke M, Feinberg S, Gould M, Baxter N, Lewis N. Colonoscopy quality assurance in Ontario: Systematic review and clinical practice guideline. Canadian journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2014 May:28(5):251-74 [PubMed PMID: 24839621]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDoubeni CA, Corley DA, Quinn VP, Jensen CD, Zauber AG, Goodman M, Johnson JR, Mehta SJ, Becerra TA, Zhao WK, Schottinger J, Doria-Rose VP, Levin TR, Weiss NS, Fletcher RH. Effectiveness of screening colonoscopy in reducing the risk of death from right and left colon cancer: a large community-based study. Gut. 2018 Feb:67(2):291-298. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312712. Epub 2016 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 27733426]

Zessner-Spitzenberg J, Waldmann E, Rockenbauer LM, Klinger A, Klenske E, Penz D, Demschik A, Majcher B, Trauner M, Ferlitsch M. Impact of Bowel Preparation Quality on Colonoscopy Findings and Colorectal Cancer Deaths in a Nation-Wide Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2024 Oct 1:119(10):2036-2044. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002880. Epub 2024 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 39007693]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSharma P, Burke CA, Johnson DA, Cash BD. The importance of colonoscopy bowel preparation for the detection of colorectal lesions and colorectal cancer prevention. Endoscopy international open. 2020 May:8(5):E673-E683. doi: 10.1055/a-1127-3144. Epub 2020 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 32355887]

Martens P, Bisschops R. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: efficacy, tolerability and safety. Acta gastro-enterologica Belgica. 2014 Jun:77(2):249-55 [PubMed PMID: 25090824]

Karsenti D, Gincul R, Belle A, Vienne A, Weiss E, Vanbiervliet G, Gronier O. Antibiotic prophylaxis in digestive endoscopy: Guidelines from the French Society of Digestive Endoscopy. Endoscopy international open. 2024 Oct:12(10):E1171-E1182. doi: 10.1055/a-2415-9414. Epub 2024 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 39411364]

Ahmad A, Saunders BP. Photodocumentation in colonoscopy: the need to do better? Frontline gastroenterology. 2022:13(4):337-341. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2021-101903. Epub 2021 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 35722601]

Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, Levin TR, Burt RW, Johnson DA, Kirk LM, Litlin S, Lieberman DA, Waye JD, Church J, Marshall JB, Riddell RH, U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2002 Jun:97(6):1296-308 [PubMed PMID: 12094842]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWitte TN, Enns R. The difficult colonoscopy. Canadian journal of gastroenterology = Journal canadien de gastroenterologie. 2007 Aug:21(8):487-90 [PubMed PMID: 17703247]

Jung Y, Lee SH. How do I overcome difficulties in insertion? Clinical endoscopy. 2012 Sep:45(3):278-81. doi: 10.5946/ce.2012.45.3.278. Epub 2012 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 22977817]

Rowland RS, Bell GD, Dogramadzi S, Allen C. Colonoscopy aided by magnetic 3D imaging: is the technique sufficiently sensitive to detect differences between men and women? Medical & biological engineering & computing. 1999 Nov:37(6):673-9 [PubMed PMID: 10723871]

Haghbin H, Zakirkhodjaev N, Aziz M. Withdrawal time in colonoscopy, past, present, and future, a narrative review. Translational gastroenterology and hepatology. 2023:8():19. doi: 10.21037/tgh-23-8. Epub 2023 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 37197256]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKwon KA, Hahm KB. Rectal Retroflexion during Colonoscopy: A Bridge over Troubled Water. Clinical endoscopy. 2014 Jan:47(1):3-4. doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.1.3. Epub 2014 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 24570876]

Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, Beil TL, Fu R. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of internal medicine. 2008 Nov 4:149(9):638-58 [PubMed PMID: 18838718]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans J, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fisher L, Fukami N, Hwang JH, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Jue TL, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Malpas PM, Maple JT, Sharaf RN, Dominitz JA, Cash BD. Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2012 Oct:76(4):707-18. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.252. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22985638]

Sharma VK, Nguyen CC, Crowell MD, Lieberman DA, de Garmo P, Fleischer DE. A national study of cardiopulmonary unplanned events after GI endoscopy. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2007 Jul:66(1):27-34 [PubMed PMID: 17591470]

Derbyshire E, Hungin P, Nickerson C, Rutter MD. Colonoscopic perforations in the English National Health Service Bowel Cancer Screening Programme. Endoscopy. 2018 Sep:50(9):861-870. doi: 10.1055/a-0584-7138. Epub 2018 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 29590669]

Reumkens A, Rondagh EJ, Bakker CM, Winkens B, Masclee AA, Sanduleanu S. Post-Colonoscopy Complications: A Systematic Review, Time Trends, and Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Studies. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2016 Aug:111(8):1092-101. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.234. Epub 2016 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 27296945]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMukewar S, Costedio M, Wu X, Bajaj N, Lopez R, Brzezinski A, Shen B. Severe adverse outcomes of endoscopic perforations in patients with and without IBD. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2014 Nov:20(11):2056-66. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000154. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25265263]

Tiwari A, Sharma H, Qamar K, Sodeman T, Nawras A. Recognition of Extraperitoneal Colonic Perforation following Colonoscopy: A Review of the Literature. Case reports in gastroenterology. 2017 Jan-Apr:11(1):256-264. doi: 10.1159/000475750. Epub 2017 May 2 [PubMed PMID: 28559786]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaspatis GA, Vardas E, Theodoropoulou A, Manolaraki MM, Charoniti I, Papanikolaou N, Chroniaris N, Chlouverakis G. Complications of colonoscopy in a large public county hospital in Greece. A 10-year study. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2008 Dec:40(12):951-7. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.02.041. Epub 2008 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 18417433]

Hawkins AT, Sharp KW, Ford MM, Muldoon RL, Hopkins MB, Geiger TM. Management of colonoscopic perforations: A systematic review. American journal of surgery. 2018 Apr:215(4):712-718. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.08.012. Epub 2017 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 28865668]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKedia P, Waye JD. Colon polypectomy: a review of routine and advanced techniques. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2013 Sep:47(8):657-65. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31829ebda7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23948754]

Kim HS, Kim TI, Kim WH, Kim YH, Kim HJ, Yang SK, Myung SJ, Byeon JS, Lee MS, Chung IK, Jung SA, Jeen YT, Choi JH, Choi KY, Choi H, Han DS, Song JS. Risk factors for immediate postpolypectomy bleeding of the colon: a multicenter study. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2006 Jun:101(6):1333-41 [PubMed PMID: 16771958]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceParaskeva KD, Paspatis GA. Management of bleeding and perforation after colonoscopy. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2014 Nov:8(8):963-72. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2014.925797. Epub 2014 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 24882203]

Ha JF, Minchin D. Splenic injury in colonoscopy: a review. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2009 Oct:7(5):424-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.07.010. Epub 2009 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 19638324]

Lukies M, Clements W. Splenic injury during colonoscopy: modern treatment approach and splenic salvage. Acta gastro-enterologica Belgica. 2022 Oct-Dec:85(4):635-636. doi: 10.51821/85.3.11004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36566374]

Zhang J, Chen G, Li Z, Zhang P, Li X, Gan D, Cao X, Du H, Zhang J, Zhang L, Ye Y. Colonoscopic screening is associated with reduced Colorectal Cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Cancer. 2020:11(20):5953-5970. doi: 10.7150/jca.46661. Epub 2020 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 32922537]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAziz M, Chandrasekar VT. The ever-growing scope of diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy. Translational gastroenterology and hepatology. 2024:9():32. doi: 10.21037/tgh-24-4. Epub 2024 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 39091652]

Brenner H, Stock C, Hoffmeister M. Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2014 Apr 9:348():g2467. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2467. Epub 2014 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 24922745]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShine R, Bui A, Burgess A. Quality indicators in colonoscopy: an evolving paradigm. ANZ journal of surgery. 2020 Mar:90(3):215-221. doi: 10.1111/ans.15775. Epub 2020 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 32086869]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiu A, Wang H, Lin Y, Fu L, Liu Y, Yan S, Chen H. Gastrointestinal endoscopy nurse assistance during colonoscopy and polyp detection: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Medicine. 2020 Aug 21:99(34):e21278. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021278. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32846754]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKamradt M, Baudendistel I, Längst G, Kiel M, Eckrich F, Winkler E, Szecsenyi J, Ose D. Collaboration and communication in colorectal cancer care: a qualitative study of the challenges experienced by patients and health care professionals. Family practice. 2015 Dec:32(6):686-93. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmv069. Epub 2015 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 26311705]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRestall G, Walker JR, Waldman C, Zawaly K, Michaud V, Moffat D, Singh H. Perspectives of primary care providers and endoscopists about current practices, facilitators and barriers for preparation and follow-up of colonoscopy procedures: a qualitative study. BMC health services research. 2018 Oct 17:18(1):782. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3567-y. Epub 2018 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 30333033]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCai W, Zhang X, Luo Y, Ye M, Guo Y, Ruan W. Quality indicators of colonoscopy care: a qualitative study from the perspectives of colonoscopy participants and nurses. BMC health services research. 2022 Aug 19:22(1):1064. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08466-5. Epub 2022 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 35986267]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence