Introduction

Acute cholecystitis involves inflammation of the gallbladder, most commonly caused by obstruction of the cystic duct by a gallstone. In fewer cases, impaired gallbladder emptying due to cholestasis and acute illness contributes to the condition.[1] Surgical intervention remains the preferred treatment, though selected patients may benefit from conservative management with antibiotics and supportive care based on clinical context.

Cholecystitis can occur with or without gallstones and is classified as either acute or chronic. Both men and women experience this condition, although women tend to have a higher susceptibility. The acute form typically presents with well-recognized signs and symptoms; however, clinical overlap with disorders, eg, peptic ulcer disease, irritable bowel syndrome, cardiac conditions, and pancreatitis, can complicate diagnosis.[2][3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Cystic duct obstruction represents the primary etiology of acute cholecystitis, often leading to bile stasis and subsequent inflammation. Under normal conditions, bile produced in the liver flows through the hepatic duct, entering the gallbladder via the cystic duct and continuing down the common bile duct into the gastrointestinal tract through the ampulla of Vater. After the ingestion of food—particularly meals high in fat—cholecystokinin (CCK) stimulates gallbladder contraction. In response, the gallbladder releases bile through the cystic duct and into the duodenum, where bile facilitates fat emulsification for efficient absorption.[5]

In addition to storing bile, the gallbladder also concentrates it. Disruption in bile homeostasis increases the risk of precipitation and stone formation. Factors contributing to this disruption include bile stasis, hepatic oversaturation of cholesterol and lipids, abnormal concentration processes, and cholesterol crystal nucleation.

When a gallstone obstructs the cystic duct, biliary colic may result, often presenting as pain or discomfort in the right upper quadrant or epigastrium. Acute calculous cholecystitis develops with persistent obstruction, leading to gallbladder distention and inflammation, typically confirmed when pain lasts longer than 6 hours. Acute acalculous cholecystitis, which occurs without gallstones, more commonly affects critically ill patients or those dependent on total parenteral nutrition (TPN) over extended periods.[6][7]

Regardless of the underlying cause, elevated intraluminal pressure within the gallbladder can increase transmural pressure, impair perfusion, and provoke inflammation. Without prompt relief, ischemia may progress to gangrene. A gangrenous gallbladder becomes vulnerable to infection by gas-forming organisms, potentially leading to emphysematous cholecystitis. These complications may culminate in gallbladder perforation, significantly raising morbidity and mortality.

Approximately 95% of individuals diagnosed with acute cholecystitis have gallstones.[8] However, incidental detection of gallstones in asymptomatic patients does not necessitate intervention. Estimates suggest that only 20% of such individuals will develop symptoms over a 20-year period, making routine prophylactic cholecystectomy unnecessary in the absence of symptoms.[9]

Epidemiology

Women, individuals with obesity, pregnant patients, and those in their 40s face a higher risk of developing gallbladder disease. Drastic weight loss or the presence of acute illnesses may further elevate this risk. A familial predisposition contributes to the formation of gallstones, indicating a genetic component in disease susceptibility.

Additionally, conditions that promote the breakdown of red blood cells, eg, sickle cell disease, contribute to an increased incidence of pigmented gallstones. These patients also show a higher likelihood of developing acute calculous cholecystitis due to the accumulation of pigment within the biliary system.

Pathophysiology

Acute cholecystitis may develop due to occlusion of the cystic duct or impaired gallbladder emptying. Inadequate bile drainage from the gallbladder leads to increased intraluminal pressure and distension, contributing to ischemia and inflammation of the gallbladder wall. Stagnant bile creates a favorable environment for bacterial colonization, further intensifying the inflammatory response.[10]

Without timely treatment, acute cholecystitis can progress to gallbladder perforation, sepsis, and potentially death. Gallstones—formed from substances such as bilirubinate or cholesterol—frequently contribute to the development of cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. In conditions, eg, sickle cell disease, the increased breakdown of red blood cells elevates serum bilirubin levels, promoting the formation of pigmented stones.[11] Patients with hyperparathyroidism and other conditions that cause elevated serum calcium levels may develop calcium-based gallstones.

Pregnant individuals face an elevated risk of gallstone formation due to delayed gallbladder emptying influenced by increased progesterone levels. Cholesterol stones represent the most commonly encountered type and tend to form in the presence of excessive cholesterol. Obstruction of the common bile duct caused by neoplasms or strictures may also disrupt bile flow and lead to stone formation due to persistent stasis.[12][13]

Histopathology

During the early phase, the gallbladder typically reveals extensive venous congestion and edema. With time, fibrosis and the presence of chronic inflammatory cells may appear. More advanced cases may present with gangrene or perforation.

History and Physical

Cholecystitis Clinical Features

Chronic cholecystitis often presents with gradually worsening right upper quadrant abdominal pain accompanied by bloating, nausea, vomiting, and intolerance to certain foods, particularly those that are greasy or spicy. Discomfort may radiate to the midback or right shoulder, and intermittent pain can persist for years before a definitive diagnosis is made.

Acute cholecystitis shares many of the same symptoms but with greater severity. The clinical presentation can resemble cardiac conditions, leading to potential diagnostic confusion. A hallmark finding of acute cholecystitis is inspiratory arrest during palpation of the right upper quadrant, commonly referred to as Murphy's sign. Episodes frequently follow a specific dietary trigger, most commonly the consumption of high-fat foods.

Evaluation

Accurate diagnosis of cholecystitis relies heavily on a thorough clinical assessment. However, laboratory studies, including a complete blood count (CBC) and a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), provide valuable diagnostic support. In chronic cholecystitis, these lab results may remain within normal limits. In contrast, acute or more severe cases often show elevated white blood cell counts (WBC) and increased liver enzymes. The presence of hyperbilirubinemia raises suspicion for a common bile duct obstruction. However, even in advanced gallbladder disease, laboratory values may occasionally remain normal.[14][15]

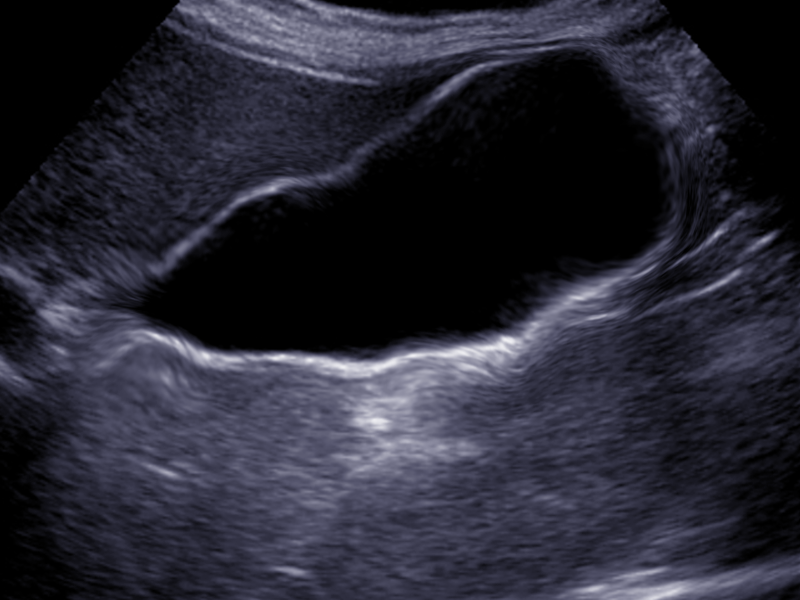

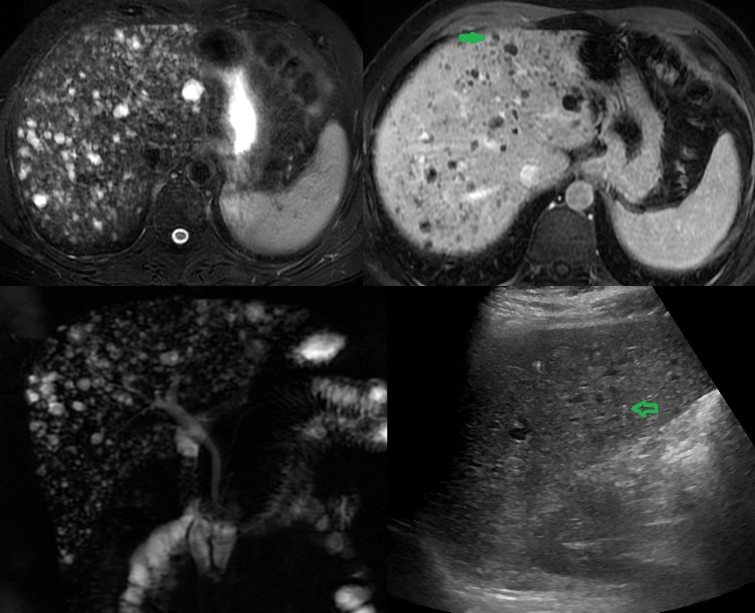

Evaluation should also include assessment of amylase and lipase levels to rule out pancreatitis. In the emergency department, a computed tomography (CT) scan frequently serves as the initial imaging study (see Images. Axial CT Abdomen Acute Cholecystitis and Abdomen CT, Acute Cholecystitis). This modality may reveal signs, including gallbladder distention, wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid, radio-opaque stones, and surrounding inflammation. When gallbladder pathology is suspected, abdominal ultrasound remains the preferred imaging method (see Images. Multiple Biliary Hamartoma and Ultrasound and Acalculous Cholecystitis). Findings suggestive of acute calculous cholecystitis include a thickened gallbladder wall >3 mm, edema, pericholecystic fluid, and the presence of gallstones (see Image. Cholecystitis).

In cases where ultrasound or CT findings do not clearly confirm acute cholecystitis, a hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan may provide diagnostic clarity. Failure of the gallbladder to fill with radiotracer indicates cystic duct obstruction and supports a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. When gallstones are absent, the use of cholecystokinin (CCK) during the HIDA scan may identify acalculous cholecystitis. An ejection fraction below 35% suggests a hypokinetic gallbladder, also referred to as biliary dyskinesia.[14][15]

Treatment / Management

Surgical Management Approaches

Initial management of acute cholecystitis typically involves intravenous fluid resuscitation and prompt initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics effective against gram-negative rods and anaerobes. For patients deemed appropriate surgical candidates, early laparoscopic cholecystectomy during the initial hospitalization remains the preferred approach. Evidence consistently demonstrates that early surgical management reduces postoperative morbidity and mortality compared to delayed intervention in hospitalized patients.[16][17] In situations where laparoscopic cholecystectomy is not suitable, an open cholecystectomy provides an alternative surgical route.(B2)

Robotic-assisted cholecystectomy may be an option depending on the surgeon's expertise. While earlier robotic systems were associated with higher rates of bile duct injury, newer-generation platforms demonstrate improved safety profiles, with fewer serious complications and a lower likelihood of conversion to an open procedure compared to traditional laparoscopy.[18][19][20](B2)

Nonsurgical Management Approaches

Patients with milder chronic cholecystitis who are not candidates for surgery may benefit from dietary modifications, particularly a low-fat diet, although outcomes vary. Medical management with ursodiol has shown occasional success in dissolving gallstones, although its effectiveness remains limited.[21][22][4]

Severely ill or high-risk patients who cannot tolerate surgery may undergo percutaneous gallbladder drainage performed by interventional radiology. This intervention may serve as definitive therapy for elderly or comorbid patients or as a bridge to elective cholecystectomy within 4 to 8 weeks of drain placement.[23] In patients who decline surgery, interventional radiology can conduct outpatient tube studies to confirm cystic duct patency before drain removal. However, recurrence rates of acute cholecystitis after drain removal may reach up to 47%.[24]

Endoscopic alternatives, eg, cystic duct stent placement or transduodenal gallbladder drainage, offer additional options for patients unfit for surgery.[25][26] These procedures remain less widely available than percutaneous cholecystostomy, and long-term outcomes require further investigation.(B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Understanding the differential diagnosis of acute cholecystitis can prevent unwanted morbidity and mortality associated with this condition. A timely and accurate diagnosis of acute cholecystitis enables early treatment and reduces the risk of complications. The differential diagnoses of acute cholecystitis include:

- Biliary colic

- Choledocholithiasis

- Cholangitis

- Pancreatitis

- Hepatitis

- Gastritis

- Hiatal hernia

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Appenditis

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Small bowel obstruction

Prognosis

Untreated acute cholecystitis carries a significant risk of morbidity and mortality, especially among older adults. Free perforation of the gallbladder, a potential complication of unmanaged cholecystitis, corresponds with a mortality rate of 30%.[27]

Timely surgical intervention markedly improves outcomes. When managed with early cholecystectomy—performed within 72 hours of symptom onset—patients experience a 30-day morbidity rate of only 6.6% and a 30-day mortality rate of 1.1%. Early treatment plays a critical role in reducing complications and improving overall survival.[17]

Complications

The complications of acute cholecystitis and associated treatments include:

- Intraabdominal abscess

- Gallbladder perforation

- Cholecystoenteric fistulas

- Biloma

- Bile duct injury

- Hepatic injury

- Bowel injury

- Infection

- Retained stones in the bile duct

- Bleeding

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Following gallbladder removal, most patients can be discharged either on the same day or the next, depending on their overall condition and recovery progress. Postoperative antibiotics may be necessary when the gallbladder shows signs of gangrene or perforation at the time of surgery.

Pain following the procedure tends to be minimal and typically responds well to over-the-counter analgesics. Some patients may report significant shoulder pain caused by retained carbon dioxide used during laparoscopic insufflation. This discomfort results from diaphragmatic irritation and generally resolves as the patient becomes more active and the gas is gradually absorbed over the course of up to 3 days.

Before leaving the hospital, patients should receive counseling about the potential for temporary intolerance to greasy foods, which may lead to bloating or diarrhea. In most cases, these symptoms diminish over time as bile production increases and the gastrointestinal system adapts. Patients who experience persistent diarrhea may benefit from bile acid sequestrants (eg, cholestyramine) to manage their symptoms effectively.

Pearls and Other Issues

Cholecystitis may develop at any age, although the highest incidence occurs during the fourth decade of life. The classic clinical profile—often summarized as “fat, forty, fertile, and flatulent”—frequently applies to those at most significant risk. Food intolerances often trigger early symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, and bloating. As the disease progresses, these symptoms may become persistent, even in the absence of food intake.

Removal of the gallbladder remains the preferred treatment. Historically performed through an open laparotomy, the procedure now typically involves laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with robotic-assisted techniques gaining popularity. This surgical approach offers low mortality and morbidity rates, a faster recovery time, and favorable long-term outcomes.

In some cases, patients present to primary care clinicians with mild or nonspecific symptoms of acute cholecystitis, posing a diagnostic challenge due to overlap with other conditions. Initial management often involves conservative measures, including dietary modification with a low-fat diet and, when appropriate, weight loss. However, many patients ultimately present to the emergency department with more severe symptoms, requiring urgent surgical intervention. Emergency procedures carry higher operative morbidity, prompting general surgeons to advocate for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy earlier in the disease course.

Additional complications may arise when gallstones migrate into the bile duct, leading to biliary obstruction or acute pancreatitis—conditions that warrant prompt recognition and treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Acute cholecystitis, or inflammation of the gallbladder, can result in infection, gangrene, or perforation if not treated promptly. Diagnosis involves physical exam, laboratory tests, and imaging such as ultrasound, CT scan, or HIDA scan. Management ranges from supportive care with fluids and antibiotics to removing the gallbladder (cholecystectomy), which is the definitive treatment in most cases. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the preferred method due to reduced recovery time and morbidity. Prompt treatment improves overall patient outcomes and reduces complications and morbidity.

Effective management of acute cholecystitis relies heavily on a coordinated interprofessional approach. Emergency department clinicians and primary care clinicians are critical in the early recognition and diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. Radiologists provide essential imaging interpretation to confirm the presence of gallstones or gallbladder inflammation. Surgeons evaluate surgical candidacy and perform cholecystectomies. Interventional radiologists may perform percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement in critically ill patients. Gastroenterologists may perform endoscopic interventions in poor surgical candidates. Cardiologists and internists assess and optimize high-risk patients preoperatively, especially those with cardiac comorbidities.

Nurses are integral in preoperative and postoperative care, monitoring vitals, managing pain, and educating patients about postoperative care. Pharmacists review medications to prevent interactions and adjust antibiotics based on culture results or allergies. In intensive care settings, where both calculous and acalculous cholecystitis may occur, critical care specialists manage hemodynamic stability and coordinate temporizing interventions like percutaneous drainage when surgery is contraindicated. Effective communication between team members, facilitated through daily rounds and shared electronic health records, ensures timely interventions and comprehensive patient care. This collaborative model not only enhances patient safety but also streamlines care, reduces complications, and shortens hospital stays.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Multiple Biliary Hamartoma, Ultrasound. This is an ultrasound (US) of a 37-year-old woman diagnosed with gallstones and acute cholecystitis. The incidental findings: (A) US image shows multiple hypoechoic lesions, some of which have comet-tail artifacts, raising the possibility of numerous biliary hamartomas. (B) A T2-weighted magnetic resonance image (MRI) shows numerous cystic lesions with a signal similar to that of cerebrospinal fluid. (C) Post-contrast T2-weighted MRI shows some of these lesions with an enhancing mural nodule, which is highly specific for biliary hamartoma. (D) Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography 3D projection image has more lesions and demonstrates no communication with a normal caliber biliary duct.

Contributed by A Borhani, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Fu Y, Pang L, Dai W, Wu S, Kong J. Advances in the Study of Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis: A Comprehensive Review. Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2022:40(4):468-478. doi: 10.1159/000520025. Epub 2021 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 34657038]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBurmeister G, Hinz S, Schafmayer C. [Acute Cholecystitis]. Zentralblatt fur Chirurgie. 2018 Aug:143(4):392-399. doi: 10.1055/a-0631-9463. Epub 2018 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 30134498]

Walsh K, Goutos I, Dheansa B. Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis in Burns: A Review. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2018 Aug 17:39(5):724-728. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irx055. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29931066]

Kohga A, Suzuki K, Okumura T, Yamashita K, Isogaki J, Kawabe A, Kimura T. Is postponed laparoscopic cholecystectomy justified for acute cholecystitis appearing early after onset? Asian journal of endoscopic surgery. 2019 Jan:12(1):69-73. doi: 10.1111/ases.12482. Epub 2018 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 29577610]

Ahmed M. Functional, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspects of Bile. Clinical and experimental gastroenterology. 2022:15():105-120. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S360563. Epub 2022 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 35898963]

Yun SP, Seo HI. Clinical aspects of bile culture in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Medicine. 2018 Jun:97(26):e11234. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011234. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29952986]

Wilkins T, Agabin E, Varghese J, Talukder A. Gallbladder Dysfunction: Cholecystitis, Choledocholithiasis, Cholangitis, and Biliary Dyskinesia. Primary care. 2017 Dec:44(4):575-597. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2017.07.002. Epub 2017 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 29132521]

Halpin V. Acute cholecystitis. BMJ clinical evidence. 2014 Aug 20:2014():. pii: 0411. Epub 2014 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 25144428]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBehari A, Kapoor VK. Asymptomatic Gallstones (AsGS) - To Treat or Not to? The Indian journal of surgery. 2012 Feb:74(1):4-12. doi: 10.1007/s12262-011-0376-5. Epub 2011 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 23372301]

Wang AJ, Wang TE, Lin CC, Lin SC, Shih SC. Clinical predictors of severe gallbladder complications in acute acalculous cholecystitis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2003 Dec:9(12):2821-3 [PubMed PMID: 14669342]

Tierney S, Nakeeb A, Wong O, Lipsett PA, Sostre S, Pitt HA, Lillemoe KD. Progesterone alters biliary flow dynamics. Annals of surgery. 1999 Feb:229(2):205-9 [PubMed PMID: 10024101]

Apolo Romero EX, Gálvez Salazar PF, Estrada Chandi JA, González Andrade F, Molina Proaño GA, Mesías Andrade FC, Cadena Baquero JC. Gallbladder duplication and cholecystitis. Journal of surgical case reports. 2018 Jul:2018(7):rjy158. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjy158. Epub 2018 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 29992010]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSureka B, Rastogi A, Mukund A, Thapar S, Bhadoria AS, Chattopadhyay TK. Gangrenous cholecystitis: Analysis of imaging findings in histopathologically confirmed cases. The Indian journal of radiology & imaging. 2018 Jan-Mar:28(1):49-54. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_421_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29692527]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTootian Tourghabe J, Arabikhan HR, Alamdaran A, Zamani Moghadam H. Emergency Medicine Resident versus Radiologist in Detecting the Ultrasonographic Signs of Acute Cholecystitis; a Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Emergency (Tehran, Iran). 2018:6(1):e19 [PubMed PMID: 30009221]

Joshi G, Crawford KA, Hanna TN, Herr KD, Dahiya N, Menias CO. US of Right Upper Quadrant Pain in the Emergency Department: Diagnosing beyond Gallbladder and Biliary Disease. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2018 May-Jun:38(3):766-793. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170149. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29757718]

Brooks KR, Scarborough JE, Vaslef SN, Shapiro ML. No need to wait: an analysis of the timing of cholecystectomy during admission for acute cholecystitis using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2013 Jan:74(1):167-73; 173-4. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182788b71. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23271092]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFugazzola P, Cobianchi L, Di Martino M, Tomasoni M, Dal Mas F, Abu-Zidan FM, Agnoletti V, Ceresoli M, Coccolini F, Di Saverio S, Dominioni T, Farè CN, Frassini S, Gambini G, Leppäniemi A, Maestri M, Martín-Pérez E, Moore EE, Musella V, Peitzman AB, de la Hoz Rodríguez Á, Sargenti B, Sartelli M, Viganò J, Anderloni A, Biffl W, Catena F, Ansaloni L, S.P.Ri.M.A.C.C. Collaborative Group. Prediction of morbidity and mortality after early cholecystectomy for acute calculous cholecystitis: results of the S.P.Ri.M.A.C.C. study. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2023 Mar 18:18(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13017-023-00488-6. Epub 2023 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 36934276]

Lunardi N, Abou-Zamzam A, Florecki KL, Chidambaram S, Shih IF, Kent AJ, Joseph B, Byrne JP, Sakran JV. Robotic Technology in Emergency General Surgery Cases in the Era of Minimally Invasive Surgery. JAMA surgery. 2024 May 1:159(5):493-499. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2024.0016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38446451]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKalata S, Thumma JR, Norton EC, Dimick JB, Sheetz KH. Comparative Safety of Robotic-Assisted vs Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. JAMA surgery. 2023 Dec 1:158(12):1303-1310. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2023.4389. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37728932]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMaegawa FB, Stetler J, Patel D, Patel S, Serrot FJ, Lin E, Patel AD. Robotic compared with laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A National Surgical Quality Improvement Program comparative analysis. Surgery. 2025 Feb:178():108772. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2024.08.006. Epub 2024 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 39277483]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceThangavelu A, Rosenbaum S, Thangavelu D. Timing of Cholecystectomy in Acute Cholecystitis. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2018 Jun:54(6):892-897. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.02.045. Epub 2018 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 29752150]

Ke CW, Wu SD. Comparison of Emergency Cholecystectomy with Delayed Cholecystectomy After Percutaneous Transhepatic Gallbladder Drainage in Patients with Moderate Acute Cholecystitis. Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques. Part A. 2018 Jun:28(6):705-712. doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0502. Epub 2018 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 29658839]

Woodward SG, Rios-Diaz AJ, Zheng R, McPartland C, Tholey R, Tatarian T, Palazzo F. Finding the Most Favorable Timing for Cholecystectomy after Percutaneous Cholecystostomy Tube Placement: An Analysis of Institutional and National Data. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2021 Jan:232(1):55-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.10.010. Epub 2020 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 33098966]

Sperry C, Malik A, Reiland A, Thornburg B, Keswani R, Ebrahim Patel MS, Aadam A, Yang A, Teitelbaum E, Salem R, Riaz A. Percutaneous Cystic Duct Interventions and Drain Internalization for Calculous Cholecystitis in Patients Ineligible for Surgery. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2023 Apr:34(4):669-676. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2022.12.468. Epub 2022 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 36581195]

Storm AC, Vargas EJ, Chin JY, Chandrasekhara V, Abu Dayyeh BK, Levy MJ, Martin JA, Topazian MD, Andrews JC, Schiller HJ, Kamath PS, Petersen BT. Transpapillary gallbladder stent placement for long-term therapy of acute cholecystitis. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2021 Oct:94(4):742-748.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.03.025. Epub 2021 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 33798540]

Troncone E, Amendola R, Moscardelli A, De Cristofaro E, De Vico P, Paoluzi OA, Monteleone G, Perez-Miranda M, Del Vecchio Blanco G. Endoscopic Gallbladder Drainage: A Comprehensive Review on Indications, Techniques, and Future Perspectives. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2024 Apr 14:60(4):. doi: 10.3390/medicina60040633. Epub 2024 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 38674279]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIndar AA, Beckingham IJ. Acute cholecystitis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2002 Sep 21:325(7365):639-43 [PubMed PMID: 12242178]