Introduction

Branchial cleft cysts are congenital anomalies arising from the first through fourth pharyngeal clefts.[1] The most common type of branchial cleft cyst arises from the second cleft, with anomalies derived from the first, third, and fourth clefts being rarer. As this is a congenital anomaly, brachial cleft cysts are present at birth, although they may not be obvious or symptomatic until later.[2] The majority of lesions present in childhood as a visible punctum on the skin of the anterior neck with or without periodic drainage; however, they may present as a neck mass or as recurrent abscesses due to infections within the tract.

Branchial cleft anomalies occur in 1 of 3 forms: cysts, sinuses, or fistulae.[3] Cysts are epithelial-lined structures that do not have external openings that connect to the skin or pharynx, and as such, may be asymptomatic and only noticed incidentally. Such cysts may not present until adulthood. Sinus tracts connect either the skin or the pharynx to a blind pouch. Sinus tracts may communicate externally with skin as a visible punctum or internally with the pharynx or larynx, where the punctum opening will only be visible on endoscopy. Branchial cleft fistulae are true communications connecting the pharynx or larynx with the external skin.[3][4][5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Branchial cleft anomalies form due to the incomplete involution of branchial cleft structures during embryonic development, and therefore follow predictable pathways. Around the fourth week of gestation, neural crest cells migrate into the future head and neck region, where the 6 pairs of branchial (pharyngeal) arches begin to develop.[3] The mesoderm of the arches is covered externally by ectoderm and internally lined by endoderm.

Normally, 5 branchial arches are present, with the arches separated by depressions known as clefts on the external, ectodermal surface and corresponding pouches on the internal, endodermal side. As a result, there are 4 pharyngeal clefts. The second arch develops caudally and then covers the third and fourth arches. These buried clefts become ectoderm-lined cavities that normally involute completely by 7 weeks of gestation.[6] If the clefts do not involute or incompletely involute, these pathological remnants will form cysts, sinuses, or fistulae in predictable locations according to their branchial cleft of origin.[7][8][9]

First Branchial Cleft Anomalies

First cleft anomalies comprise 5% to 25% of all branchial cleft anomalies and are further categorized using the Work classification system. Work type I lesions contain ectoderm only and, on physical examination, present as preauricular masses or sinuses that track anterior and medial to the external auditory canal, localized within the preauricular region. These typically present lateral to the facial nerve and end within the external auditory canal or connect to the umbo of the middle ear, essentially a duplication of the membranous external auditory canal without skin adnexa.

Work type II lesions are more common and contain both ectodermal and mesodermal elements within the auditory canal duplication, which results in the development of cartilage and skin adnexa in addition to the squamous epithelium. These classically present with a punctum at the angle of the mandible or within the submandibular region, although if the lesion is a sinus tract without an opening on the face, there may be a parotid mass or drainage from the external auditory canal.[10] Their relationship to the facial nerve is variable, passing superficial to (57%), deep to (30%), or between (13%) branches of the facial nerve.[11]

Second Branchial Cleft Anomalies

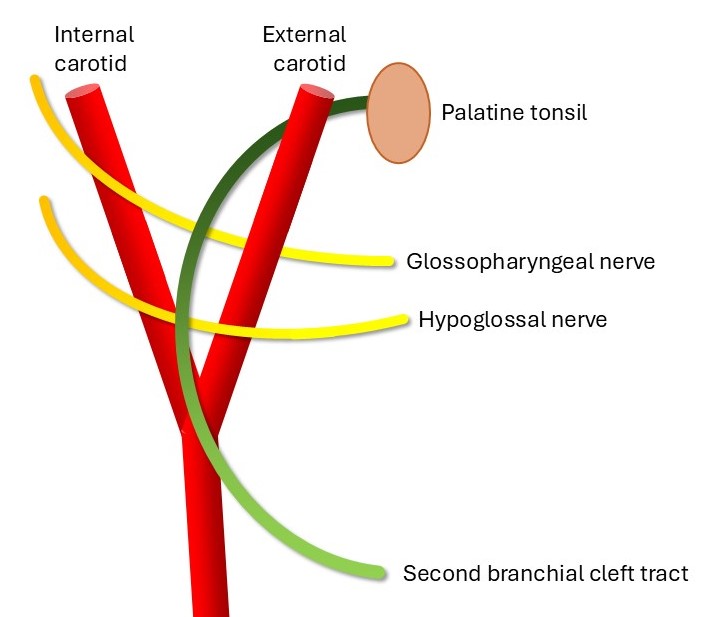

This is the most common branchial cleft anomaly, representing approximately 40% to 95% of cases (see Image. Schematic of the Second Branchial Cleft Tract). The external punctum is found anterior and medial to the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) on the neck skin. Bilateral second-branchial cleft cysts can be associated with branchio-oto-renal syndrome.

The course of a second branchial cleft sinus is as follows: the external opening is located on the anterior neck, with the fistula traveling deep to the platysma and then passing in between the internal and external carotid arteries, coursing superficial to the glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves before ending in the tonsillar fossa. Cysts or sinuses of the second branchial cleft can occur anywhere along this course.[12][13]

Third Branchial Cleft Anomalies

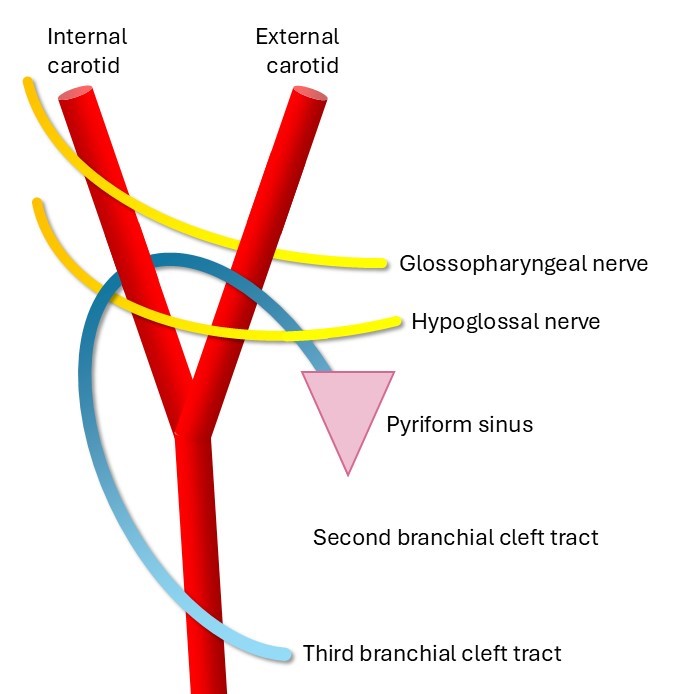

Third branchial cleft anomalies are estimated to represent 2% to 8% of all branchial cleft anomalies (see Image. Schematic of the Third Branchial Cleft Tract). When present, the external skin opening is seen over the middle to lower third of the anterior SCM. The third branchial cleft tract courses as follows: from the skin opening in the low anterior neck, the tract runs deep to the platysma and then posterior to the internal carotid artery. The tract passes between the glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves and may be intimately associated with the superior laryngeal nerve, classically coursing superior to it. The tract then connects to the pyriform sinus in the hypopharynx.[14]

Fourth Branchial Cleft Anomalies

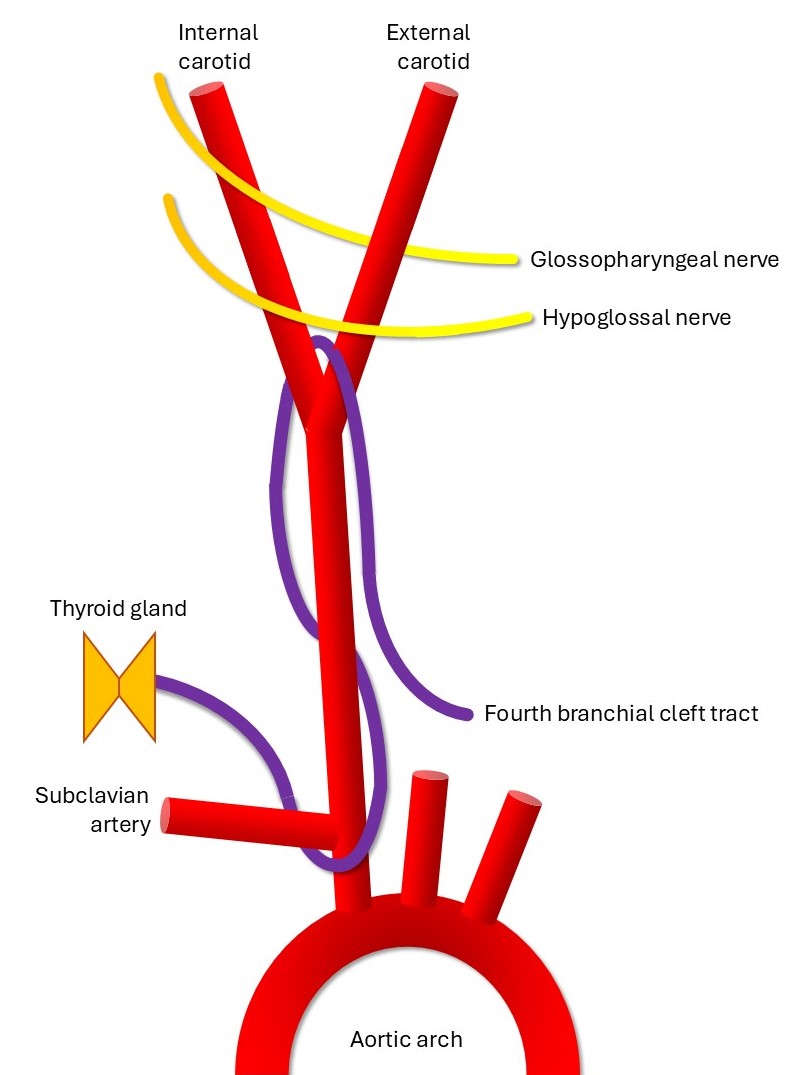

Fourth cleft anomalies are extremely rare, representing approximately 1% of all branchial cleft anomalies (see Image. Schematic of the Fourth Branchial Cleft Tract). They are reported more commonly on the left, with the skin opening near the medial lower border of the SCM. The exact course of the fourth branchial cleft remnant is not well characterized owing to its rarity. However, the fourth branchial cleft tract is usually described as passing deep to the common carotid artery and looping around either the aortic arch (in a left-sided anomaly) or the subclavian artery (in a right-sided anomaly). These run superficial to the recurrent laryngeal nerve and hypoglossal nerve, terminating in the upper lobe of the thyroid gland.[6][14]

Epidemiology

The true incidence of branchial cleft anomalies is unknown despite their relatively high frequency as the most common congenital anomaly of the neck. This is likely due to the variety of both the anomalies and their presentations, which complicates accurate reporting, particularly when the clinicians to whom these patients present are unaware of the condition.

Branchial cleft anomalies have no ethnic predilection, although first branchial cleft anomalies are more common in females, and fourth branchial cleft anomalies are more common on the left side.[10] Most branchial cleft anomalies arise from the second pouch, while the first, third, and fourth pouches are rarer, and 10% of branchial cleft anomalies are bilateral. These typically present in the first decade of life, but the presentation may be delayed into adulthood if no external communication is present.[5]

Pathophysiology

Branchial cleft cysts are embryologic anomalies that arise from errors during the complex development of the pharyngeal apparatus. They may present as fistulae, cysts, or sinus tracts and are clinically encountered laterally in the anterior neck, just medial to the SCM. Lesions below the clavicles are more likely to be epidermoid or dermoid cysts rather than branchial remnants, and midline neck anomalies are more likely to be thyroglossal duct cysts.

Branchio-oto-renal (BOR) and branchio-oculofacial (BOF) syndromes should be suspected when a patient presents with preauricular pits or multiple branchial cleft anomalies, including bilateral anomalies. These syndromes are autosomal dominant conditions associated with hearing loss, ear malformations, and, in the BOR syndrome, renal anomalies as well. BOF includes eye anomalies (eg, microphthalmia and obstructed lacrimal ducts) and facial anomalies (eg, cleft lip and palate).[5]

Histopathology

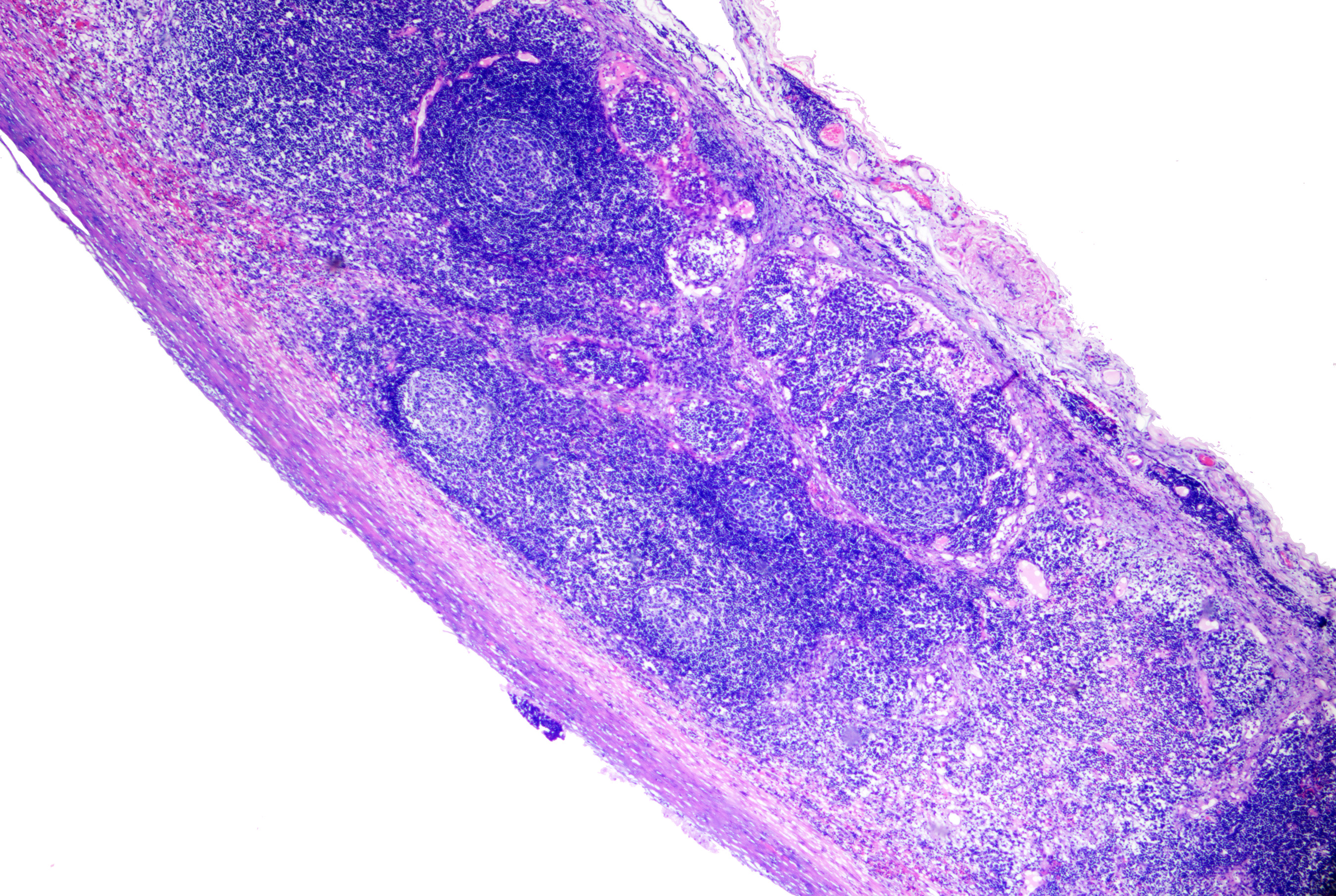

Branchial cleft cysts are lined with stratified squamous epithelium and may contain keratinous debris inside the cyst. In some cases, the cyst wall is lined by ciliated columnar epithelium, resulting in more mucoid contents. Lymphoid tissue is typically present surrounding the epithelial lining. If the cyst is infected or ruptured, inflammatory cells can be identified in the cavity or stroma (see Image. Branchial Cyst on Histopathology).[5]

History and Physical

Clinical History

Branchial cleft cysts are often asymptomatic but can become tender, enlarged, or inflamed with superinfection or abscess formation during episodes of upper respiratory tract infections. In such situations, the patient can present with purulent drainage from the sinus to the skin or pharynx. The most concerning symptoms include dysphagia, dyspnea, and stridor due to compression of the upper airway.[15]

Cystic lesions are more common than fistulae, but they usually present later, in the second decade of life. Cysts most often present as nontender soft-tissue masses beneath the sternocleidomastoid muscle. However, they may present with acute infection. Change in size during upper respiratory infections is noted in up to 25% of branchial cleft anomalies.

Physical Examination

The physical examination will differ depending on the location of the branchial cleft cyst.

First branchial cleft anomalies

A first branchial cleft anomaly is typically a smooth, nontender, fluctuant mass found between the external auditory canal and the submandibular area. Frequently, it will have a cutaneous punctum from which fluid may be expressed. A first branchial cleft anomaly is variably involved with the parotid gland and facial nerve, and there may be a connection to the middle or external ear, making an otologic examination crucial in these patients.[16]

Work type I anomalies track anterior and medial to the external auditory canal, lateral to the facial nerve, and end within the external auditory canal or connect to the umbo of the middle ear, causing a mass in the preauricular region. Work type II tracts are classically present at the angle of the mandible or within the submandibular region and are located deep or medial to the facial nerve.[12]

Second branchial cleft anomalies

A second branchial cleft anomaly is typically identified by a pit or punctum of the skin at the lower anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid. It may connect to the tonsillar fossa of the pharynx. The lesions are tender if secondarily infected and may lead to airway compromise in severe cases. If a second branchial cleft anomaly is associated with a sinus tract, mucoid or purulent discharge may be present on the skin or into the pharynx.[17][18]

Third and fourth-branchial cleft anomalies

Third and fourth-branchial cleft anomalies are rare. They are more commonly found on the left side of the neck or the suprasternal notch/supraclavicular area. Typically, they present as a firm mass or infected cyst draining to the piriform sinus or external neck skin. These fistulae are more likely to present when infected, and they may have undergone repeated incision and drainage procedures owing to incorrect diagnosis and subsequent recurrence.[19] Fourth-branchial cleft cysts may present as recurrent thyroid abscesses.

Evaluation

Imaging Studies

- If a sinus tract is present, a sinogram can be obtained by injecting radiopaque dye to delineate the course and determine the size of the cyst.

- Ultrasonography can be used to determine the characteristics of the cyst.[1][20]

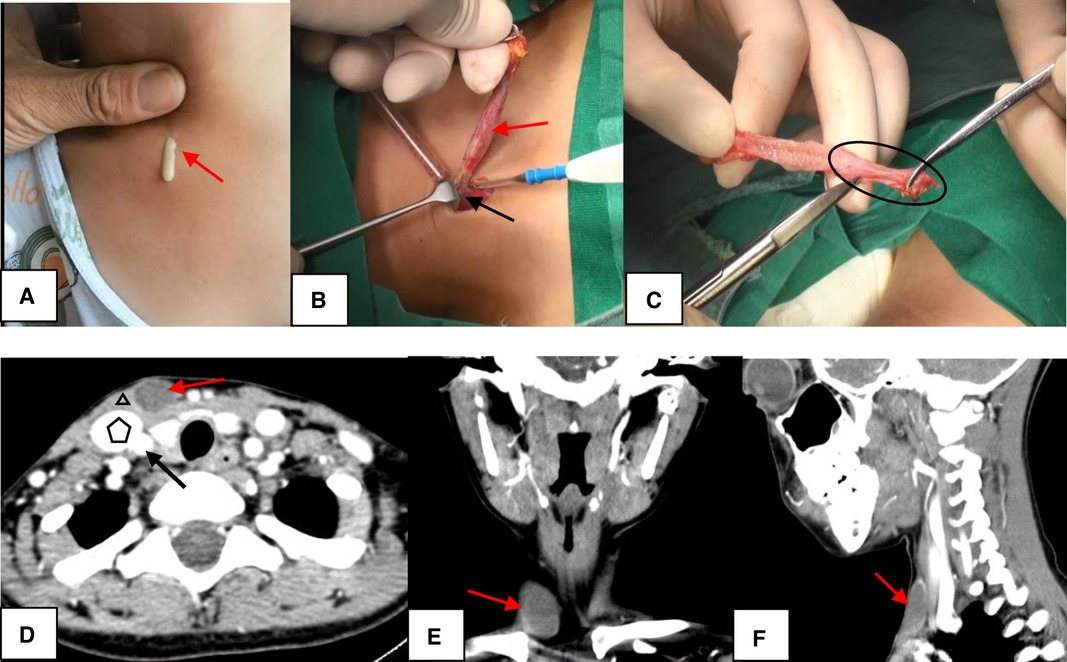

- Contrast-enhanced computed tomography will identify a cystic mass in the neck. However, it may not offer sufficient resolution to follow the course of the tract (see Image. Second Branchial Left Anomaly.).[21]

- Magnetic resonance imaging can be considered when finer resolution is needed or used in pediatric patients to avoid radiation from computed tomography.[22]

Fine-needle aspiration is helpful in distinguishing a branchial cleft cyst from a malignant neoplasm, such as a squamous cell carcinoma, which may also present as a unilateral, cystic neck lesion.[17]

Treatment / Management

The primary treatment approach for a branchial cleft cyst is elective excision to reduce the risk of infection, further enlargement, or, very rarely, development of a malignancy, eg, squamous cell carcinoma. As long as no airway compromise or frank abscess develops, the operation typically has no urgency; surgeons can defer excision beyond 3 to 6 months of age or allow resolution of an acute infection.[5] However, emergent surgery may be required in the event of airway compromise or a large abscess.[23][24] In the acutely infected setting, systemic antibiotics and aspiration are generally preferable to incision and drainage, which may produce distortion and scarring of anatomical planes, thus potentially complicating a future surgical excision.[25](B2)

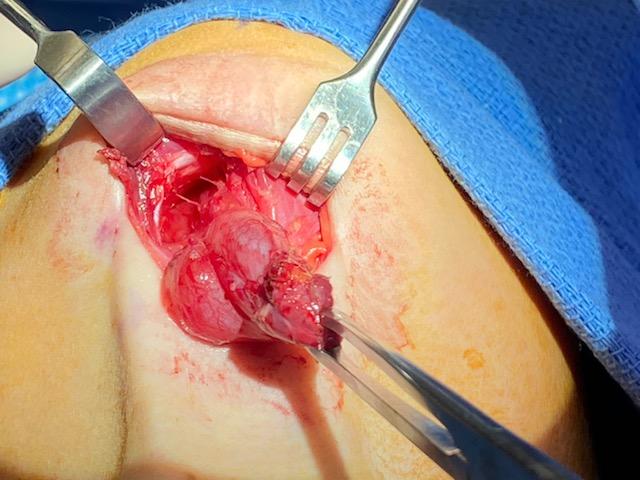

The incision is planned to optimize cosmesis, placing the incision within a natural skin crease whenever possible, but taking care to excise any external opening completely. If a fistula or sinus is present, identifying the tract by gently inserting a lacrimal probe or catheter will facilitate complete excision and decrease the chance of recurrence (see Image. Excision of a Right Second Branchial Cleft Cyst With Tract). Methylene blue can be employed by dipping a lacrimal probe in the solution and inserting it into the tract to make it easier to visualize intraoperatively. Dissection should be performed carefully over the surface of the lesion as the tract can be thin-walled (see Image. Right Second Branchial Cleft Cyst). If the tract is long, exposure should be obtained by using a second "stepladder" incision placed within a skin crease cephalad to the primary incision.

In the case of first branchial cleft cysts, initial exposure of the main trunk of the facial nerve and branches should be performed with a superficial parotidectomy approach to reduce the risk of facial nerve injury, as the anomaly may be intimately associated with the nerve. Preoperative fistulograms may also be useful.[9][26] Third and fourth branchial cleft cysts are treated with a standard transverse cervical incision to identify and protect the recurrent laryngeal nerve, occasionally requiring thyroid lobectomy to completely excise the tract to the piriform sinus. Before the transcervical portion of the surgery is begun, direct laryngoscopy is performed to confirm the diagnosis and to allow endoscopic cannulation of the opening into the piriform sinus to facilitate dissection during excision.[5][27] Tracts opening into the upper aerodigestive tract may be challenging to access surgically, and Bugbee monopolar electrocautery may be used through an endoscope to ablate the mucosa and seal the lumen.

Ablation Therapy

In the event that a patient cannot undergo surgery or refuses a neck incision, ethanol ablation has been used as an alternative. However, this approach is not usually recommended as a primary treatment.[9][28] Other sclerotherapy agents that have been used, with or without ultrasound guidance, include OK-432 (picibanil), doxycycline, tetracycline, and bleomycin.[29][30][31] An endoscopic, minimally invasive retroauricular approach has also been described as an alternative to transcervical resection, with similarly low rates of complications and recurrence, but a slightly longer operative time.[32][33][34](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Other neck masses that may present similarly to branchial cleft anomalies include:

- Lymphadenopathy (reactive, infectious, inflammatory, and malignant)

- Dermoid/epidermoid cyst

- Hemangioma

- Plunging ranula

- Carotid body tumor

- Lymphatic malformation (cystic hygroma)

- Ectopic thyroid/salivary tissue

- Vascular neoplasm/malformation

- Thyroglossal duct cyst

- Foregut duplication cyst

- Cat scratch disease

- Atypical mycobacterial infections

- Cystic squamous cell carcinoma

- Thyroid goiter

- Thyroid neoplasm

- Thyroid abscess [1][5]

Staging

First branchial cleft anomalies are classified using the following Work system, developed in 1972:

- Type 1: Less common and includes ectoderm only. They are localized to the preauricular area, typically superficial to the facial nerve, and consist of a skin-only reduplication of the external auditory canal, usually connected to the external auditory canal itself.

- Type 2: This type includes ectoderm and mesodermal elements which track more inferiorly, ending with a punctum by the angle of the mandible or in the submandibular region. If no punctum is present, a parotid mass may be present. Reduplication of the external auditory canal also occurs, but with cartilage and skin adnexa; the relationship to the facial nerve is variable and may be deep to it, superficial to it, or running between branches.[11]

Second branchial cleft anomalies are classified using the following Bailey system, developed in 1929:

- Type 1: The cyst or sinus is located deep to the platysma, along the anterior portion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, but does not extend deeply enough to contact the carotid sheath in type 1 anomalies.

- Type 2: This is the most common type, in which the cyst or sinus is located deep to the anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, posterior to the submandibular gland, and is laterally adjacent to the carotid sheath.

- Type 3: This type is the least common, in which the tract courses from the anterior neck, between the external and internal carotid arteries, and opens into the lateral pharyngeal wall.

- Type 4: The cyst or sinus is located deep to the carotid sheath and opens into the lateral pharyngeal wall in type 4 anomalies.[17]

In essence, the Bailey system represents a progression in which type 1 represents only the most superficial aspect of the classically described second branchial cleft tract. Type 2 includes a deeper portion of the tract that extends down to, but not deep to, the carotid arteries, while type 3 is the entire tract described above (see Image. Schematic of the Second Branchial Cleft Tract). Type 4 is only the deepest component of the tract.

Prognosis

Patients and families should be educated that branchial cleft cysts are typically benign, and with appropriate surgical management, patients generally recover without complications or recurrence.

Complications

Once branchial cleft cysts are excised, recurrence is relatively uncommon, with an estimated risk of 3%. However, if previous surgery or recurrent infection has occurred, recurrence rates can be as high as 20% because of the increased difficulty of complete surgical resection.[5]

Consultations

Depending on the patient's age, an otolaryngologist, pediatric otolaryngologist, or head and neck surgical oncologist should be consulted to determine the need for surgical resection.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Branchial cleft anomalies are congenital malformations, and currently, there are no preventative measures to reduce the likelihood of presentation. Patients and physicians should be educated on the symptomatology and physical examination findings that may lead to earlier diagnosis of these lesions, more appropriate imaging evaluation, and consequent reduction of complications. This will also reduce the cost of care for the patient, which would otherwise consist of repeated physician visits, multiple courses of antibiotics, and diagnostic imaging.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Due to the complexity of the condition and its comparative rarity, recognition, evaluation, and management of branchial cleft anomalies are optimally performed by an interprofessional team. This collaborative effort involves otolaryngologists, primary care clinicians, emergency care, pathologists, radiologists, anesthesia clinicians, nurses, pharmacists, and hospital staff. An otolaryngologist or pediatric surgeon usually performs surgical excision of these lesions. Although complete removal is the preferred treatment, medical management may be necessary in cases of infection or abscess formation.

The 2 most common complications of branchial cleft anomalies are recurrence and infection. In rare cases, iatrogenic injury to the facial nerve or other cranial nerves may also occur, requiring further treatment. In general, outcomes after branchial cleft anomaly removal are excellent, with only a 3% to 7% recurrence rate.[25][26]

Surgeons undertaking excision of branchial cleft anomalies must have a comprehensive understanding of head and neck embryology, pathophysiology, and anatomy to anticipate the tract's potential course and accomplish a complete resection without injury to surrounding structures. Preoperative and postoperative care should include educating patients and caregivers about branchial cleft cysts, tracts, and fistulae, as well as the importance of complete excision to prevent recurrence. Specialty-trained nurses in otolaryngology and pediatric surgery are involved in this counseling as well as postoperative care and monitoring for complications.

Clear and effective communication among healthcare team members is essential for achieving good outcomes and minimizing complications. Surgical specialists must promptly identify signs of infected branchial cleft anomalies and advise against incision and drainage or partial removal, as these interventions can lead to scarring, recurrence, and complications, eg, nerve or vascular injury. Open communication supports timely diagnosis and treatment decisions, reducing errors and enhancing patient safety. Ongoing education and training ensure that healthcare practitioners remain current on best practices for managing branchial cleft anomalies.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Second Branchial Cleft Anomaly. In Image A, the sinus appears as a skin pit on the lateral neck with discharge from the skin opening (red arrow). In Image B, the sinus (red arrow) terminates at the surface of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle (black arrow). In Image C, the end of the sinus closes, forming a muscle bundle (circle) that ends at the surface of the SCM. In Images D to F, computed tomography scans show the lesion (red arrow) lying along the anterior surface of the SCM (triangle), just deep to the platysma and not in contact with the carotid sheath (pentagon: internal jugular vein; black arrow: common carotid artery). Image D represents the axial view, Image E the coronal view, and Image F the sagittal view.

Chen W, Zhou YU, Xu M, et al. Congenital second branchial cleft anomalies in children: a report of 52 surgical cases, with emphasis on characteristic CT findings. Front Pediatr. 2023;11:1088234.

doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1088234.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Schematic of the Fourth Branchial Cleft Tract. The tract runs from the thyroid gland or larynx to the anterior supraclavicular neck, coursing posterior to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, looping under the subclavian artery (under the aortic arch on the left side), ascending deep to the common carotid artery, and passing between the internal and external carotid arteries.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

References

Patel S, Bhatt AA. Thyroglossal duct pathology and mimics. Insights into imaging. 2019 Feb 6:10(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0694-x. Epub 2019 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 30725193]

Bahakim A, Francois M, Van Den Abbeele T. Congenital Midline Cervical Cleft and W-Plasty: Our Experience. International journal of otolaryngology. 2018:2018():5081540. doi: 10.1155/2018/5081540. Epub 2018 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 30627168]

Banakis Hartl RM, Said S, Mann SE. Bilateral Ear Canal Cholesteatoma with Underlying Type I First Branchial Cleft Anomalies. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2019 Apr:128(4):360-364. doi: 10.1177/0003489418821700. Epub 2019 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 30607978]

Meng F, Zhu Z, Ord RA, Zhang T. A unique location of branchial cleft cyst: case report and review of the literature. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2019 Jun:48(6):712-715. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2018.11.014. Epub 2018 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 30579743]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceProsser JD, Myer CM 3rd. Branchial cleft anomalies and thymic cysts. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2015 Feb:48(1):1-14 [PubMed PMID: 25442127]

Oh JH, Chang YW, Lee EJ. Sonographic diagnosis of coexisting ectopic thyroid and fourth branchial cleft cyst. Journal of clinical ultrasound : JCU. 2018 Nov:46(9):582-584. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22630. Epub 2018 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 30288756]

Tazegul G, Bozoğlan H, Doğan Ö, Sari R, Altunbaş HA, Balci MK. Cystic lateral neck mass: Thyroid carcinoma metastasis to branchial cleft cyst. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics. 2018 Oct-Dec:14(6):1437-1438. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.188440. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30488872]

Williams DS. Neck Mass in a Five-year-old Afghan Child. Journal of insurance medicine (New York, N.Y.). 2018 Jan:47(3):191-193. doi: 10.17849/insm-47-03-191-193.1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30192721]

Koch EM, Fazel A, Hoffmann M. Cystic masses of the lateral neck - Proposition of an algorithm for increased treatment efficiency. Journal of cranio-maxillo-facial surgery : official publication of the European Association for Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery. 2018 Sep:46(9):1664-1668. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.06.004. Epub 2018 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 29983308]

Adams A, Mankad K, Offiah C, Childs L. Branchial cleft anomalies: a pictorial review of embryological development and spectrum of imaging findings. Insights into imaging. 2016 Feb:7(1):69-76. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0454-5. Epub 2015 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 26661849]

Work WP. Newer concepts of first branchial cleft defects. The Laryngoscope. 1972 Sep:82(9):1581-93 [PubMed PMID: 5079586]

Bajaj Y, Ifeacho S, Tweedie D, Jephson CG, Albert DM, Cochrane LA, Wyatt ME, Jonas N, Hartley BE. Branchial anomalies in children. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2011 Aug:75(8):1020-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.05.008. Epub 2011 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 21680029]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMuller S, Aiken A, Magliocca K, Chen AY. Second Branchial Cleft Cyst. Head and neck pathology. 2015 Sep:9(3):379-83. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0592-y. Epub 2014 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 25421295]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNicoucar K, Giger R, Pope HG Jr, Jaecklin T, Dulguerov P. Management of congenital fourth branchial arch anomalies: a review and analysis of published cases. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2009 Jul:44(7):1432-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.12.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19573674]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePossel L, François M, Van den Abbeele T, Narcy P. [Mode of presentation of fistula of the first branchial cleft]. Archives de pediatrie : organe officiel de la Societe francaise de pediatrie. 1997 Nov:4(11):1087-92 [PubMed PMID: 9488742]

Xiao H, Kong W, Gong S, Wang J, Liu S, Shi H. [Surgical treatment of first branchial cleft anomaly]. Lin chuang er bi yan hou ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology. 2005 Oct:19(19):873-4 [PubMed PMID: 16419954]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShen LF, Zhou SH, Chen QQ, Yu Q. Second branchial cleft anomalies in children: a literature review. Pediatric surgery international. 2018 Dec:34(12):1251-1256. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4348-8. Epub 2018 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 30251021]

Lee DH, Yoon TM, Lee JK, Lim SC. Clinical Study of Second Branchial Cleft Anomalies. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2018 Sep:29(6):e557-e560. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004540. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29608472]

Quintanilla-Dieck L, Penn EB Jr. Congenital Neck Masses. Clinics in perinatology. 2018 Dec:45(4):769-785. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2018.07.012. Epub 2018 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 30396417]

Bansal AG, Oudsema R, Masseaux JA, Rosenberg HK. US of Pediatric Superficial Masses of the Head and Neck. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2018 Jul-Aug:38(4):1239-1263. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170165. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29995618]

Friedman E, Patiño MO, Udayasankar UK. Imaging of Pediatric Salivary Glands. Neuroimaging clinics of North America. 2018 May:28(2):209-226. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2018.01.005. Epub 2018 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 29622115]

Brown RE, Harave S. Diagnostic imaging of benign and malignant neck masses in children-a pictorial review. Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery. 2016 Oct:6(5):591-604 [PubMed PMID: 27942480]

Prada LR, Koripalli VS, Merino CL, Fulger I. A Case of a Rapidly Enlarging Neck Mass with Airway Compromise. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2017 May:11(5):OD14-OD16. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25685.9874. Epub 2017 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 28658834]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchmidt K, Leal A, McGill T, Jacob R. Rapidly enlarging neck mass in a neonate causing airway compromise. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2016 Apr:29(2):183-4 [PubMed PMID: 27034563]

Mattioni J, Azari S, Hoover T, Weaver D, Chennupati SK. A cross-sectional evaluation of outcomes of pediatric branchial cleft cyst excision. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2019 Apr:119():171-176. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.01.030. Epub 2019 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 30735909]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAhn D, Lee GJ, Sohn JH. Comparison of the Retroauricular Approach and Transcervical Approach for Excision of a Second Brachial Cleft Cyst. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2017 Jun:75(6):1209-1215. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.12.008. Epub 2016 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 28061361]

Teng SE, Paul BC, Brumm JD, Fritz M, Fang Y, Myssiorek D. Endoscope-assisted approach to excision of branchial cleft cysts. The Laryngoscope. 2016 Jun:126(6):1339-42. doi: 10.1002/lary.25711. Epub 2015 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 26466762]

Ha EJ, Baek SM, Baek JH, Shin SY, Han M, Kim CH. Efficacy and Safety of Ethanol Ablation for Branchial Cleft Cysts. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2017 Dec:38(12):2351-2356. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5373. Epub 2017 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 28970243]

Kim MG, Kim SG, Lee JH, Eun YG, Yeo SG. The therapeutic effect of OK-432 (picibanil) sclerotherapy for benign neck cysts. The Laryngoscope. 2008 Dec:118(12):2177-81. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3181864acf. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19029851]

Kim JH. Ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy for benign non-thyroid cystic mass in the neck. Ultrasonography (Seoul, Korea). 2014 Apr:33(2):83-90. doi: 10.14366/usg.13026. Epub 2014 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 24936500]

Talmor G, Nguyen B, Mir G, Badash I, Kaye R, Caloway C. Sclerotherapy for Benign Cystic Lesions of the Head and Neck: Systematic Review of 474 Cases. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2021 Dec:165(6):775-783. doi: 10.1177/01945998211000448. Epub 2021 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 33755513]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChen LS, Sun W, Wu PN, Zhang SY, Xu MM, Luo XN, Zhan JD, Huang X. Endoscope-assisted versus conventional second branchial cleft cyst resection. Surgical endoscopy. 2012 May:26(5):1397-402. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2046-x. Epub 2011 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 22179440]

Chen L, Huang X, Lou X, Xhang S, Song X, Lu Z, Xu M. [A comparison between endoscopic-assisted second branchial cleft cyst resection via retroauricular hairline approach and conventional second branchial cleft cyst resection]. Lin chuang er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology head and neck surgery. 2013 Nov:27(22):1258-62 [PubMed PMID: 24616985]

Meijers S, Meijers R, van der Veen E, van den Aardweg M, Bruijnzeel H. A Systematic Literature Review to Compare Clinical Outcomes of Different Surgical Techniques for Second Branchial Cyst Removal. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2022 Apr:131(4):435-444. doi: 10.1177/00034894211024049. Epub 2021 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 34137276]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence