Introduction

Blepharochalasis syndrome is a rare eyelid disorder characterized by recurrent, painless episodes of edema predominantly affecting the upper eyelids and, occasionally, the lower eyelids.[1] These episodes typically begin in childhood or early adolescence, displaying a pattern of exacerbations and remissions. Each edema episode usually lasts approximately 2 days. However, repeated occurrences cumulatively cause significant changes to the periorbital tissues.[2] Over time, the periorbital skin may demonstrate atrophy, wrinkling, thinning, and discoloration, often described as having a “tissue paper-like” appearance.[3] Beyond these distinctive skin changes, blepharochalasis can cause additional clinical manifestations, including ptosis, acquired blepharophimosis, lower eyelid retraction, pseudoepicanthal folds, proptosis, and prolapse of orbital fat and lacrimal gland tissue.[4]

Blepharochalasis has been recognized in clinical practice since its first description by Beer in 1807, and the term, derived from the Greek meaning “eyelid slackening,” was introduced by Fuchs in 1896. Despite this longstanding awareness, the precise cause and the biological processes driving the condition remain largely unknown. Histological investigations reveal that elastolytic processes, involving degradation of elastic fibers, and inflammatory mechanisms potentially mediated by immunoglobulin A contribute significantly to disease progression.

Treatment primarily involves surgical correction of the anatomical changes caused by blepharochalasis.[5] A comprehensive understanding of the natural history, clinical features, and differential diagnosis is essential for effective management, particularly in preventing complications such as overcorrection or recurrence following surgery. This activity aims to integrate current knowledge on clinical characteristics, proposed pathophysiology, diagnostic challenges, and therapeutic options for blepharochalasis syndrome.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Blepharochalasis syndrome is characterized by recurrent episodes of painless, nonpitting edema in the upper eyelids, leading to gradual atrophy and laxity of the periorbital tissues.[6] Although recognized for over 2 centuries, the precise etiology of this condition remains unclear, with several hypotheses proposed to explain its pathology. While most cases are confined to the eyelids, some reports describe blepharochalasis associated with systemic abnormalities.[7] Consequently, some authors suggest that blepharochalasis may represent part of a broader systemic disorder.[8][9] Proposed etiological theories include hormonal influences, allergies, localized cutis laxa, and idiopathic angioedema. However, recent histopathological studies indicate a potential role for immunoglobulin A (IgA) deposits in the etiopathogenesis of this disease.[10][11]

One theory supports an immunological mechanism underlying blepharochalasis syndrome. Research highlights the involvement of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), specifically MMP-3 and MMP-9, in the degradation of elastic fibers within the dermis.[12] Immunohistochemical analyses reveal elevated expression of these enzymes in affected tissues, supporting the hypothesis that postinflammatory MMP release drives elastolytic and collagenolytic activity observed in blepharochalasis patients. Additionally, some studies have identified IgA antibodies directed against elastic fibers, suggesting an autoimmune component in the disease mechanism.

Hormonal factors appear to influence the etiology of blepharochalasis syndrome, as its typical onset occurs during adolescence.[13] The postpubertal emergence of the disorder suggests that hormonal fluctuations may trigger or exacerbate the disease. However, specific hormonal pathways involved remain unidentified, warranting further investigation. Environmental and lifestyle factors have also been proposed as potential triggers for the acute edema episodes characteristic of blepharochalasis syndrome. Various precipitating factors have been reported anecdotally, including menstruation, upper respiratory infections, amyloidosis, bee stings, excessive crying, physical exercise, emotional stress, and minor eyelid trauma.[14][15][16] Despite these associations, definitive causal links remain unproven, and many cases lack identifiable triggers.

A genetic predisposition has been suggested in blepharochalasis syndrome.[17] Although most cases occur sporadically, familial clusters point to a possible hereditary component. Genetic determinants and inheritance patterns remain unclear, necessitating further research into genetics. Isolated cases also document associations between blepharochalasis and systemic abnormalities. In 1920, Ascher described a triad comprising blepharochalasis, cheilitis granulomatosa, and nontoxic thyroid enlargement, now recognized as Ascher syndrome.[18][19]

Epidemiology

Accurate epidemiological data on blepharochalasis syndrome are unavailable due to its rarity. Existing information derives primarily from case reports and small case series. Onset typically occurs in childhood or puberty. Episodes recur every 3 to 4 months over several years, decreasing in frequency with age. Inflammatory attacks eventually cease, and the disease progresses to a quiescent phase.

A retrospective cohort study conducted at Beijing Tongren Eye Center analyzed 93 patients diagnosed with blepharochalasis between January 2009 and December 2019. Results indicated that 72.04% of patients were female, demonstrating a higher incidence in female individuals despite involvement of both sexes. The mean age at onset was 10.09 years, with 83.87% of patients presenting symptoms during puberty, suggesting a predilection for adolescents. The average duration from initial acute attacks to the quiescent stage was approximately 7.33 years, highlighting the chronic course of the disease.

Koursh et al conducted a review summarizing 67 cases of blepharochalasis documented from 1977 to 2006. Among these cases, 45 were female and 22 were male, corroborating the observation of higher prevalence in female patients. However, the limited sample size and potential reporting biases warrant caution when interpreting these results. The average age of onset was 11 years, with a mean follow-up period of 11.4 years. The condition presented unilaterally in 27 cases and bilaterally in 40 cases.

Fuchs’ initial description notably emphasized bilateral involvement. Acute edema attacks typically lasted several hours to a few days, averaging 2 days. In early disease stages, episodes occurred 3 to 4 times a year, though weekly exacerbations have also been reported. The study indicated that episodes of eyelid swelling generally decreased in frequency with age, leading most cases to enter a largely quiescent phase.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of blepharochalasis syndrome is controversial, with the precise mechanisms underlying the disease yet to be elucidated. Recent histopathological studies in a limited number of cases offer new insights into the condition's pathogenesis. The defining feature involves recurrent episodic inflammation, which induces tissue edema and subsequent structural damage. Acute episodes produce nonpitting edema caused by increased vascular permeability and localized fluid accumulation within the loose connective tissue of the upper eyelid. Although the edema typically resolves spontaneously and remains asymptomatic, repeated episodes result in permanent changes to eyelid anatomy. These acute inflammatory events resemble localized angioedema, where an unidentified trigger leads to vascular dysfunction, causing fluid extravasation and swelling.

A primary mechanism driving tissue deterioration involves the activity of MMPs, specifically MMP-3 and MMP-9. These enzymes degrade extracellular matrix components, including collagen and elastin, which maintain the structural integrity of the eyelid. Immunohistochemical analyses demonstrate elevated MMP expression during active blepharochalasis stages, implicating increased enzyme activity in ongoing elastolysis and collagen degradation. The loss of elastin and collagen produces clinically apparent atrophic, thin, and redundant skin.

Repeated episodes of skin stretching contribute to fragmentation and eventual loss of elastic fibers, leading to tissue atrophy. The presence of IgA deposits within the dermis and perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrates, reported in multiple studies, suggests a possible immune-mediated process. Kaneoya et al performed reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction to assess elastin messenger ribonucleic acid expression in cultured fibroblasts from a patient with blepharochalasis. Results showed no difference compared to healthy controls, indicating that environmental factors or other matrix components may contribute to the loss of elastic fibers. Blood tests, including cell counts, circulating immunoglobulins, C-reactive protein, complements C3 and C4, and C1-esterase inhibitor, have been reported as normal in patients.[20]

Histopathology

Histopathological studies of skin biopsies have enhanced understanding of the pathogenesis of blepharochalasis. A consistent finding in these specimens is the loss of dermal elastic fibers, which appear attenuated, fractured, or absent when stained with elastic tissue-specific dyes. This elastic fiber deterioration correlates with the clinical presentation of skin laxity and redundancy in individuals affected by the condition. The initial event likely involves an IgA immune-mediated reaction targeting these fibers, as multiple recent studies have demonstrated IgA antibody deposits via immunofluorescence. Immunohistochemical staining has also revealed positivity for metalloproteinases MMP-3 and MMP-9, which are implicated in other elastolytic disorders, suggesting their involvement in the pathogenesis of this condition. Additional histological features include dermal atrophy affecting various structures, increased number and diameter of skin capillaries, perivascular inflammatory infiltrates, and pigmentation within the papillary and upper reticular dermis.

History and Physical

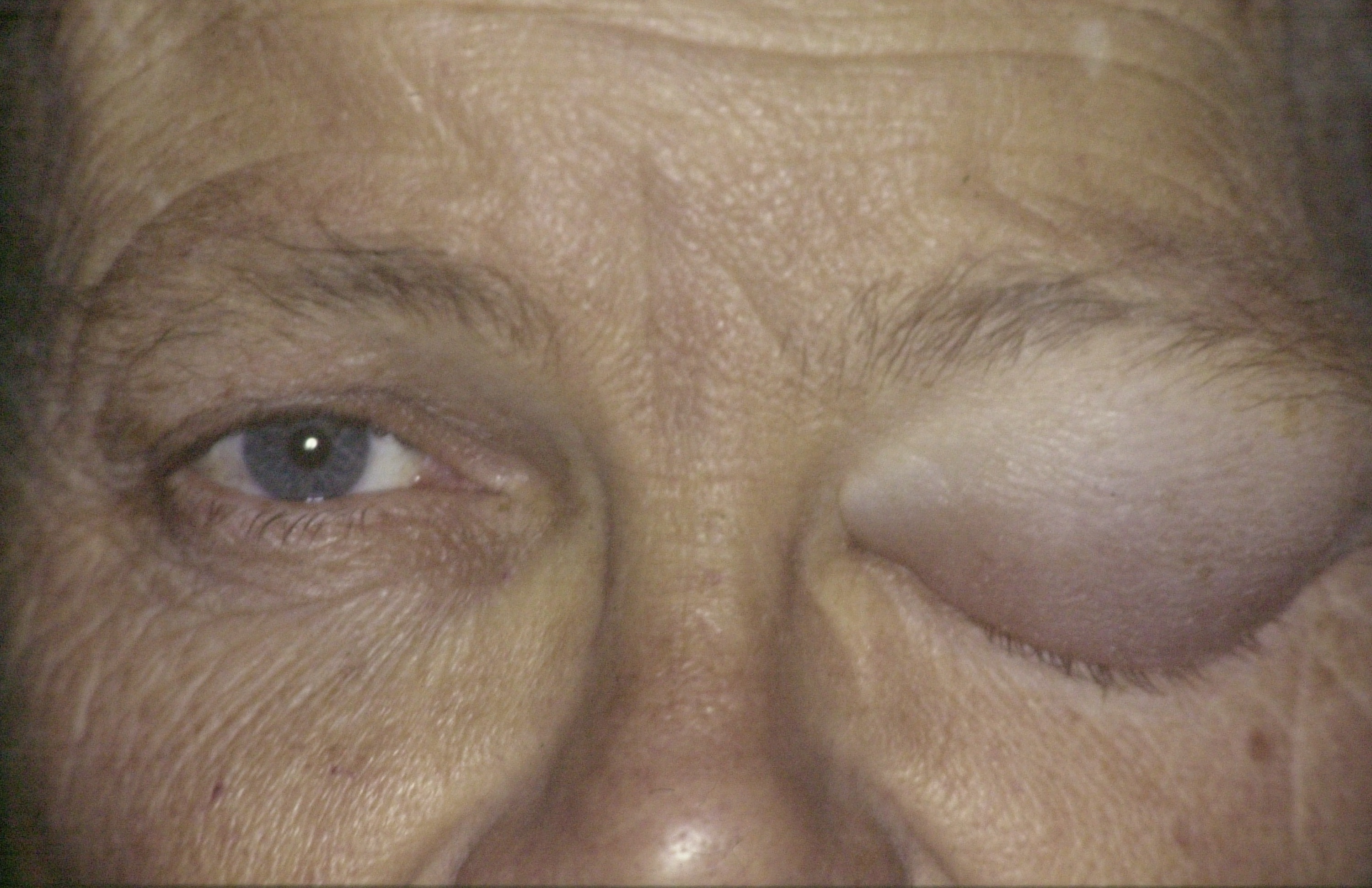

Blepharochalasis syndrome typically presents with a characteristic clinical history and physical examination findings that reflect its episodic and progressive nature.[21] Understanding these features is essential for prompt diagnosis and differentiation from other eyelid disorders. The average patient experiences recurrent episodes of painless edema primarily affecting the upper eyelids and, less commonly, the lower eyelids (see Image. Blepharochalasis, Acute Eyelid Edema Episode). The edema typically appears nonpitting and is resistant to treatments such as antihistamines and corticosteroids. Conjunctival hyperemia may develop in some cases.

Episodes often last several hours to days and frequently resolve spontaneously without intervention. Edema typically affects both eyelids but can occasionally present unilaterally.[22] Patients commonly report a sensation of weight or fullness during episodes, without accompanying pain or soreness. Potential triggers include minor trauma, illnesses, menstruation, or emotional stress. However, many patients report no identifiable precipitating factors.

Acute episodes of swelling typically persist for several hours to days, with an average duration of 2 days. Initial attacks may occur 3 to 4 times a year, although weekly exacerbations have been documented.[23] The frequency of episodes often declines with advancing age. Painless, nonpitting edema develops during these episodes, frequently accompanied by skin erythema (see Image. Blepharochalasis, Recurrent Unilateral Eyelid Swelling). Patients may also report red eyes and tearing.

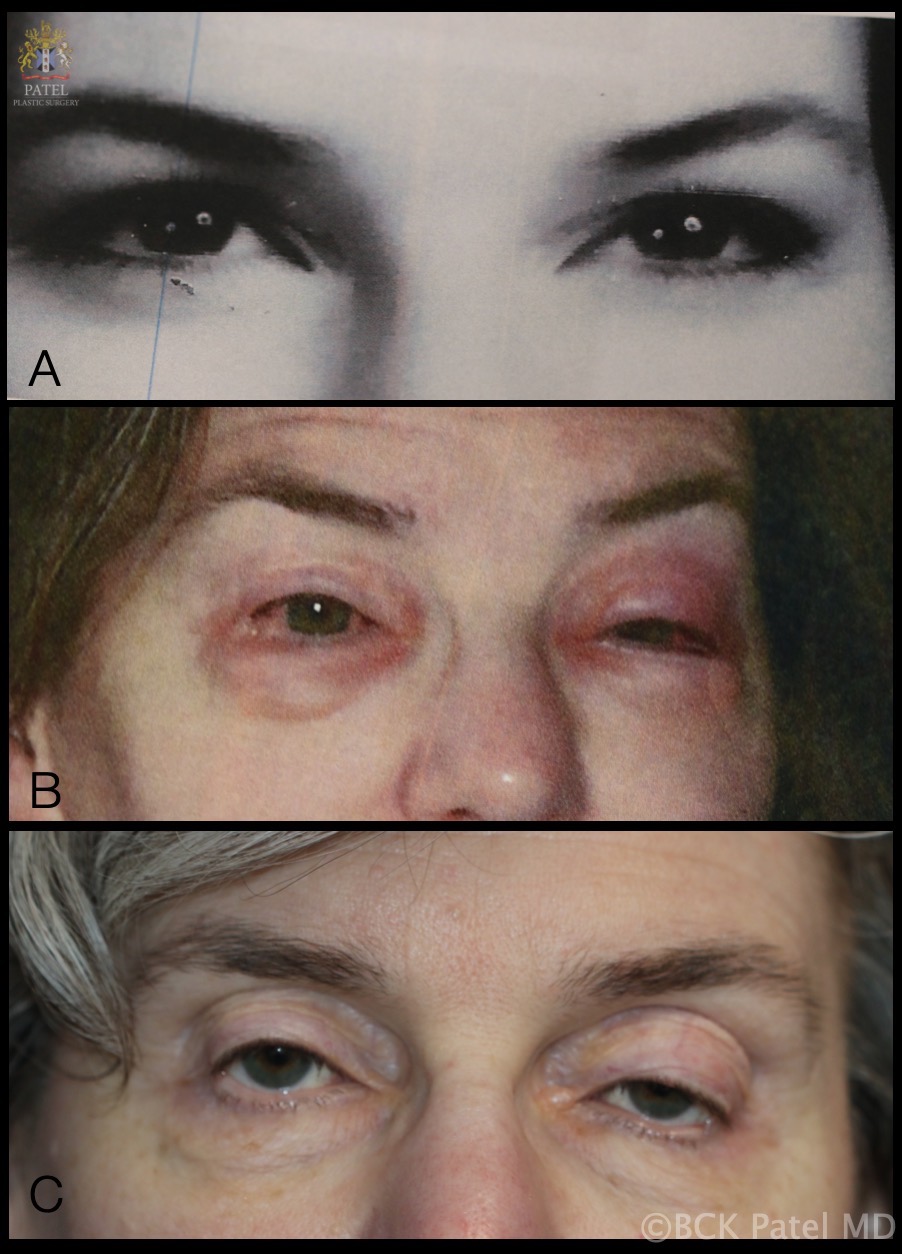

Repeated episodes of eyelid swelling produce a characteristic appearance of the eyelids and periocular area, including upper lid ptosis, wrinkled, discolored, and atrophic skin, and dilated visible subcutaneous vessels (see Image. Evolution of Blepharochalasis Syndrome). In advanced disease stages, disinsertion of the ligamentous structures of the lateral canthus causes a rounded lateral angle and shortening of the horizontal palpebral aperture, known as acquired blepharophimosis.[24] Progressive levator aponeurosis dehiscence accentuates upper lid ptosis, particularly medially. Orbital septum weakening facilitates prolapse of orbital fat and lacrimal gland in some patients. Nasal fat pad atrophy in the upper eyelid may create a pronounced nasal hollow and a pseudoepicanthal fold. Unilateral proptosis has also been reported, suggesting possible orbital involvement.

Collin proposed a classification scheme based on a series of 30 patients. The system distinguished between an active or early phase, characterized by swelling episodes, and a quiescent or late stage, defined by at least 2 years without attacks.[25] Blepharochalasis may also present as part of a systemic disease. In such cases, examination of additional anatomical regions is necessary. The most frequent associations include Ascher syndrome, characterized by blepharochalasis, double lip, and nontoxic thyroid enlargement, as well as acquired cutis laxa, which features redundant skin, skeletal anomalies, and multiple organ impairments.[26]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of blepharochalasis syndrome is based on its characteristic natural history and clinical findings during both acute and quiescent stages. A thorough differential diagnosis must be established to exclude other conditions. Although blood tests and imaging may be performed in some cases, their primary role is to rule out alternative diagnoses, as complementary test results in blepharochalasis syndrome are typically normal. Thyroid function panels, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and autoimmune markers may help exclude disorders such as thyroid eye disease or systemic lupus erythematosus.

Imaging investigations are seldom required but may be beneficial in atypical cases or when ocular fat prolapse or orbital masses are suspected. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scans can delineate soft tissue involvement and help exclude neoplastic or inflammatory diseases.[27][28] Ultrasound biomicroscopy may also aid in identifying changes within the eyelid soft tissues.

Histopathologic assessment through biopsy is rarely performed but can offer diagnostic insight in uncertain cases. The presence of elastin degradation, vascular changes, IgA deposits, and dermal atrophy can help differentiate blepharochalasis syndrome from other eyelid disorders.[29][30] Visual field testing, particularly automated perimetry, is important for evaluating functional visual impairment in patients with significant eyelid laxity or ptosis, informing management decisions, especially regarding surgical intervention.[31]

Treatment / Management

Managing blepharochalasis syndrome is complicated by its chronic and recurrent nature and the lack of standardized treatment guidelines. The primary objectives are to manage acute edema episodes, prevent long-term tissue damage, and address both functional and aesthetic eyelid deformities. Treatment should focus on reducing swelling during the acute phase and correcting structural changes during the quiescent stage.

Protocols have not been established for treating the inflammatory attacks. During acute episodes of swelling, conservative approaches, such as cold compresses, may be used to minimize inflammation and edema. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may provide symptomatic relief. However, evidence supporting medical treatment is limited. Several authors have reported favorable outcomes with systemic or topical corticosteroids, although these findings are based on small case series and indicate only partial improvement.[32] Given the risk of adverse effects, particularly with systemic steroid use, corticosteroids are not widely accepted as standard therapy for blepharochalasis syndrome, though they may be considered selectively.[33] Other immunosuppressive agents, including topical tacrolimus, have also been explored as therapeutic options.[34](B2)

Karakonji et al reported improvement in 2 patients with blepharochalasis syndrome during the acute stage using oral doxycycline, based on its properties as an MMP inhibitor.[35] Oral acetazolamide has been reported in 2 case series with good outcomes. The rationale for using this diuretic is based upon the suggestion that blepharochalasis syndrome represents a localized eyelid form of angioedema.[36](B3)

Apart from these varied attempts with limited success in managing the acute inflammatory attacks, the treatment of blepharochalasis syndrome is primarily surgical and aims to correct the resulting complications. Surgery is indicated for patients in the quiescent phase, provided the disease has remained inactive for 6 to 12 months. Performing surgery during active disease significantly increases the likelihood of treatment failure. The most frequent sequelae include dermatochalasis with either fat prolapse or fat atrophy, upper lid ptosis, lacrimal gland prolapse, and malposition of the lateral canthus or lower eyelid.

All these complications require tailored surgical correction using a broad range of techniques that must be combined based on individual presentation. Blepharoplasty, ptosis repair, and canthal procedures are technically more challenging in these patients due to the unique alterations affecting periocular tissues. Reconstructive efforts often involve tissue repositioning, fat grafting, and surgical modification of tendons, the levator aponeurosis, and the lacrimal gland.[37](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Blepharochalasis syndrome presents significant diagnostic challenges due to its rarity and the clinical overlap it shares with other eyelid disorders characterized by edema, laxity, or structural skin changes. Precise differentiation is essential to avoid inappropriate treatment and guide appropriate management. Diagnostic confusion is most likely during the acute phase, particularly at the onset of inflammatory episodes. A thorough differential diagnosis must be considered, encompassing all possible causes of acute or acute-on-chronic eyelid swelling, including the following:

- Allergic reactions [38]

- Local eyelid infection or inflammation (eg, stye, chalazion) [39]

- Orbital inflammation

- Ocular cellulitis [40]

- Contact dermatitis [41]

- Angioedema [42]

- Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome [43]

- Rosacea [44]

During the quiescent phase, the following entities may mimic blepharochalasis:

- Dermatochalasis [45]

- Floppy eyelid syndrome [46]

- Lax eyelid syndrome [47]

- Upper lid ptosis [48]

- Acquired cutis laxa [49]

- Prolapsed orbital adipose tissue [50]

- Eyelid or orbital masses and tumors [51]

- Lymphoma [52]

The differential diagnosis varies significantly between the acute and quiescent phases. Clinicians must tailor their assessment to the disease stage to avoid misdiagnosis.

Staging

Currently, a globally recognized staging system for blepharochalasis syndrome does not exist, primarily due to the rarity of the condition and its heterogeneity in clinical presentation. Nonetheless, proposed classifications aim to describe the severity of the disease based on clinical features and functional impairment, providing a framework to inform therapeutic strategies. Blepharochalasis syndrome may progress through distinct clinical phases. Recognizing the phase of progression is critical for appropriate diagnosis and intervention. In the active phase, patients experience recurrent episodes of painless, nonpitting edema affecting the upper eyelids. These episodes occur without lasting skin changes, and visual function typically remains intact. Ptosis is generally absent or only mildly present.

During the transitional phase, repeated episodes of edema result in intermittent eyelid laxity and moderate ptosis. Early signs of skin atrophy, wrinkling, and minor orbital fat protrusion may become apparent. The frequency of edema episodes often declines as structural tissue changes become more pronounced. The quiescent phase represents the chronic stage of the disease. At this point, persistent eyelid skin laxity, thinning, and redundancy are observed. Mechanical ptosis may develop, sometimes resulting in visual field restriction due to excessive skin. Orbital fat herniation is often present, and episodes of edema are infrequent or absent. This phase-based framework helps determine the appropriate timing for surgical intervention. Surgery is typically reserved for the quiescent phase, when the disease has stabilized, and functional or cosmetic concerns warrant correction.

Prognosis

The natural course of blepharochalasis syndrome typically involves a gradual reduction in the frequency of eyelid edema episodes with advancing age. Most cases eventually enter a predominantly dormant phase. The episodic swelling often resolves spontaneously over several years, frequently after puberty or in early adulthood, leading to a quiescent stage marked by infrequent episodes. The damage to the eyelid skin caused by repeated inflammatory events is generally irreversible, resulting in cosmetic deformity and functional impairment, particularly ptosis that affects the superior visual field. Early diagnosis and appropriate monitoring can help prevent unnecessary interventions during the active stage. The extent and severity of complications vary among patients.

Surgical correction performed during the quiescent phase generally yields favorable outcomes in restoring eyelid function and appearance. Multiple procedures may be required due to progressive tissue laxity. Recurrence of edema following surgery is uncommon when the operation is appropriately timed during disease inactivity. Long-term follow-up is advised to identify potential complications such as eyelid malposition or scarring. The influence of surgical intervention on future recurrence remains uncertain.

Complications

Blepharochalasis syndrome is a non-sight-threatening disease. Complications are rare and primarily affect periocular anatomy. However, recurrent episodes of eyelid swelling can lead to the following:

- Dermatochalasis, with periocular fat atrophy in some cases and fat prolapse in others

- Thin, wrinkled, atrophic, and discolored skin

- Upper eyelid ptosis with preserved levator function, suggesting aponeurotic dehiscence

- Lateral, and occasionally medial, canthal disinsertion, causing a rounded canthal angle and shortening of the horizontal palpebral fissure (acquired blepharophimosis)

- Pseudoepicanthal fold formation

- Lacrimal gland prolapse

- Lower eyelid laxity and malposition

- Secondary ocular surface irritation

Although complications are uncommon, their potential to cause functional and cosmetic impairment should be recognized. Early detection and intervention can help mitigate these effects and preserve eyelid function.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Blepharochalasis syndrome is a rare condition with an unknown etiology and no universally recognized curative treatment. The syndrome causes no severe consequences for the patient's vision. Familiarity with the disease prevents delays in diagnosis, which can provoke patient anxiety. Instructions on eyelid cleanliness, mild skin care, and avoidance of excessive friction or pressure on the eyelids can help reduce inflammation. During acute bouts, symptomatic alleviation strategies, including cold compresses and head elevation, should be recommended.

After diagnosis, patients must be informed about the condition, potential triggers, and local measures that may be attempted during swelling episodes, such as applying cold compresses. Patients should also be warned about other diseases that mimic blepharochalasis syndrome and advised to seek care during episodes of swelling to confirm the diagnosis. Prompt referral to an oculoplastic surgeon is necessary to assess functional impairment and plan surgery during the inactive phase.

Pearls and Other Issues

A crucial clinical insight in blepharochalasis syndrome lies in identifying its distinctive episodic, painless, nonpitting eyelid edema that begins during adolescence. Distinguishing this presentation from other eyelid conditions prevents misdiagnosis and inappropriate therapy. The timing of surgical intervention is critical. Surgery performed during the active phase may worsen edema and produce unfavorable outcomes. Surgical procedures should be reserved for the quiescent phase when inflammation has subsided. Careful surgical planning that considers the extent of skin laxity, ptosis severity, and orbital fat prolapse improves results and minimizes complications. Limited awareness of blepharochalasis syndrome among practitioners, due to its rarity, often causes delayed diagnosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Blepharochalasis syndrome frequently presents a diagnostic challenge due to its rarity and broad differential diagnosis. Ophthalmologists and oculoplastic surgeons play a central role in diagnosis, monitoring, and surgical management, relying on specialized knowledge of eyelid anatomy and function to achieve optimal outcomes. Primary care clinicians play a crucial role in the early detection, timely referral, and management of comorbid conditions. Although ophthalmologists serve as the primary specialists for diagnosis and treatment, management within an interprofessional team is essential.

Other specialties, such as primary care, rheumatology, and dermatology, help exclude systemic associations of the syndrome. Radiologists support diagnosis through neuroimaging when indicated, and pathologists provide critical input when a skin biopsy is performed. Nurses also play a significant role by educating patients and their families about the condition. Effective communication among all team members ensures prompt, patient-centered care. Collaborative decision-making with patients fosters realistic expectations and active involvement, thereby improving satisfaction and clinical outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Evolution of Blepharochalasis Syndrome. A sequence of photographs documenting disease progression. (A) Patient-supplied photo at age 18. (B) Bilateral periorbital swelling during a typical episode. (C) Current appearance at age 54, demonstrating periorbital tissue atrophy, levator aponeurosis dehiscence, loss of upper eyelid and brow fat, and skin thinning.

Contributed by Professor Bhupendra C. K. Patel MD, FRCS

References

Bergin DJ, McCord CD, Berger T, Friedberg H, Waterhouse W. Blepharochalasis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1988 Nov:72(11):863-7 [PubMed PMID: 3207663]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKoursh DM, Modjtahedi SP, Selva D, Leibovitch I. The blepharochalasis syndrome. Survey of ophthalmology. 2009 Mar-Apr:54(2):235-44. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.12.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19298902]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFila K. [Fuchs' blepharochalasis]. Ceskoslovenska oftalmologie. 1971 Sep:27(5):273-81 [PubMed PMID: 5110674]

Çakmak S, Göncü T. Lacrimal gland prolapse in two cases of blepharochalasis syndrome and its treatment. International ophthalmology. 2014 Apr:34(2):293-5. doi: 10.1007/s10792-013-9766-y. Epub 2013 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 23543253]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhou J, Ding J, Li D. Blepharochalasis: clinical and epidemiological characteristics, surgical strategy and prognosis-- a retrospective cohort study with 93 cases. BMC ophthalmology. 2021 Aug 28:21(1):313. doi: 10.1186/s12886-021-02049-4. Epub 2021 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 34454463]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHeld JL, Schneiderman P. A review of blepharochalasis and other causes of the lax, wrinkled eyelid. Cutis. 1990 Feb:45(2):91-4 [PubMed PMID: 2178883]

Ghose S, Kalra BR, Dayal Y. Blepharochalasis with multiple system involvement. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1984 Aug:68(8):529-32 [PubMed PMID: 6743619]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrowning RJ, Sanchez AT, Mullins S, Sheehan DJ, Davis LS. Blepharochalasis: something to cry about. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2017 Mar:44(3):279-282. doi: 10.1111/cup.12841. Epub 2016 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 27718529]

Zhao ZL, Wang SM, Shao CY, Fu Y. Ascher syndrome: a rare case of blepharochalasis combined with double lip and Hashimoto's thyroiditis. International journal of ophthalmology. 2019:12(6):1044-1046. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2019.06.26. Epub 2019 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 31236366]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMotegi S, Uchiyama A, Yamada K, Ogino S, Takeuchi Y, Ishikawa O. Blepharochalasis: possibly associated with matrix metalloproteinases. The Journal of dermatology. 2014 Jun:41(6):536-8. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12503. Epub 2014 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 24815765]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaul M, Geller L, Nowak-Węgrzyn A. Blepharochalasis: A rare cause of eye swelling. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2017 Nov:119(5):402-407. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.07.036. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29150067]

Laronha H, Caldeira J. Structure and Function of Human Matrix Metalloproteinases. Cells. 2020 Apr 26:9(5):. doi: 10.3390/cells9051076. Epub 2020 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 32357580]

Jordan DR. Blepharochalasis syndrome: a proposed pathophysiologic mechanism. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 1992 Feb:27(1):10-5 [PubMed PMID: 1555128]

Yahya F, Kesenheimer E, Decard BF, Sinnreich M, Wand D, Goldblum D. Gelsolin-Amyloidosis - An Exceptional Cause of Blepharochalasis. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2021 Apr:238(4):349-352. doi: 10.1055/a-1386-3051. Epub 2021 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 33930908]

Finney JL,Peterson HD, Blepharochalasis after a bee sting. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1984 May; [PubMed PMID: 6718584]

Koka K, Patel BC. Ptosis Correction. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969650]

Kaneoya K, Momota Y, Hatamochi A, Matsumoto F, Arima Y, Miyachi Y, Shinkai H, Utani A. Elastin gene expression in blepharochalasis. The Journal of dermatology. 2005 Jan:32(1):26-9 [PubMed PMID: 15841657]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSala Trull D, Redón Martínez A, Porcar Saura S. [Ascher syndrome: More than just a lip disorder]. Semergen. 2024 Jan-Feb:50(1):102102. doi: 10.1016/j.semerg.2023.102102. Epub 2023 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 37827048]

Rewri P, Garg S, Kumar R, Gupta G. A Century of Laffer-Ascher Syndrome. Indian journal of plastic surgery : official publication of the Association of Plastic Surgeons of India. 2023 Dec:56(6):540-543. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1776140. Epub 2023 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 38105880]

Grassegger A, Romani N, Fritsch P, Smolle J, Hintner H. Immunoglobulin A (IgA) deposits in lesional skin of a patient with blepharochalasis. The British journal of dermatology. 1996 Nov:135(5):791-5 [PubMed PMID: 8977684]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrar BK, Puri N. Blepharochalasis--a rare entity. Dermatology online journal. 2008 Jan 15:14(1):8 [PubMed PMID: 18319025]

Langley KE, Patrinely JR, Anderson RL, Thiese SM. Unilateral blepharochalasis. Ophthalmic surgery. 1987 Aug:18(8):594-8 [PubMed PMID: 3658315]

Ismail A, Khalid MO, Ismail MS, Fatima U, Ashraf MF. A rare sight: Childhood blepharochalasis presenting as recurrent eyelid swelling: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2024 Aug:121():110047. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2024.110047. Epub 2024 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 39029214]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNeuhouser AJ, Zeppieri M, Harrison AR. Blepharophimosis Syndrome. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 37276318]

Collin JR. Blepharochalasis. A review of 30 cases. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1991:7(3):153-7 [PubMed PMID: 1911519]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDantas SG, Trope BM, de Magalhães TC, Azulay DR, Quintella DC, Ramos-E-Silva M. Blepharochalasis: A rare presentation of cutis laxa. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2019 May:110(4):327-329. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2018.04.006. Epub 2019 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 30722931]

Atzeni M, Ceratola E, Zaccheddu E, Manca A, Saba L, Ribuffo D. Surgical correction and MR imaging of double lip in Ascher syndrome: record of a case and a review of the literature. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2009 Jul-Aug:13(4):309-11 [PubMed PMID: 19694346]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLin Z, Dean A, Rene C. Delayed migration of soft tissue fillers in the periocular area masquerading as eyelid and orbital pathology. BMJ case reports. 2021 Mar 18:14(3):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-241356. Epub 2021 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 33737282]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchaeppi H, Emberger M, Wieland U, Metze D, Bauer JW, Pohla-Gubo G, Thaller-Antlanger H, Hintner H. [Unilateral blepharochalasis with IgA-deposits]. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 2002 Sep:53(9):613-7 [PubMed PMID: 12207266]

Xin Y, Xu XL, Li Y, Ding JW, Li DM. [Clinical histopathologic characteristics of lacrimal glands in lacrimal gland prolapse with blepharochalasis]. [Zhonghua yan ke za zhi] Chinese journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Mar 11:56(3):205-210. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0412-4081.2020.03.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32187949]

Klingele J, Kaiser HJ, Hatt M. [Automated perimetry in ptosis and blepharochalasis]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 1995 May:206(5):401-4 [PubMed PMID: 7609399]

Drummond SR, Kemp EG. Successful medical treatment of blepharochalasis: a case series. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2009:28(5):313-6. doi: 10.3109/01676830903071190. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19874128]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDworak DP, Patel SA, Thompson LS. An Unusual Case of Blepharochalasis. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2017 Jul-Sep:12(3):342-344. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_104_15. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28791070]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRazmi T M, Takkar A, Chatterjee D, De D. Blepharochalasis: 'drooping eyelids that raised our eyebrows'. Postgraduate medical journal. 2018 Nov:94(1117):666-667. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2018-135706. Epub 2018 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 29936417]

Karaconji T, Skippen B, Di Girolamo N, Taylor SF, Francis IC, Coroneo MT. Doxycycline for treatment of blepharochalasis via inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2012 May-Jun:28(3):e76-8. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31822ddf6e. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21946773]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLazaridou MN, Sandinha T, Kemp EG. Oral acetazolamide: A treatment option for blepharochalasis? Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2007 Sep:1(3):331-3 [PubMed PMID: 19668490]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHundal KS, Mearza AA, Joshi N. Lacrimal gland prolapse in blepharochalasis. Eye (London, England). 2004 Apr:18(4):429-30 [PubMed PMID: 15069442]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGarcía-Ortega P, Mascaró F, Corominas M, Carreras M. Blepharochalasis misdiagnosed as allergic recurrent angioedema. Allergy. 2003 Nov:58(11):1197-8 [PubMed PMID: 14616136]

Loth C, Miller CV, Haritoglou C, Messmer ESBM. [Hordeolum and chalazion : (Differential) diagnosis and treatment]. Der Ophthalmologe : Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft. 2022 Jan:119(1):97-108. doi: 10.1007/s00347-021-01436-y. Epub 2021 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 34379160]

Zeppieri M, Bourget D. Periorbital Cellulitis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261970]

Hsu JI, Pflugfelder SC, Kim SJ. Ocular complications of atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2019 Sep:104(3):189-193 [PubMed PMID: 31675394]

Wang G, Li C, Gao T. Blepharochalasis: a rare condition misdiagnosed as recurrent angioedema. Archives of dermatology. 2009 Apr:145(4):498-9. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19380685]

BAZEX A, DUPRE A. [Chronic lymphedematous, sarcoid and adenomatous infiltrations of the face: Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, Stevens' fibroedema and Ascher's syndrome]. Toulouse medical. 1957 Feb:58(2):89-109 [PubMed PMID: 13422463]

Tavassoli S, Wong N, Chan E. Ocular manifestations of rosacea: A clinical review. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2021 Mar:49(2):104-117. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13900. Epub 2021 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 33403718]

Mooij JJ, van de Lande LS, Pool SMW, Stevens HPJD, van der Lei B, van Dongen JA. The rainbow scale for the assessment of dermatochalasis of the female upper eyelid: A validated scale. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2023 Jan:76():15-17. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2022.11.004. Epub 2022 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 36512997]

Thakur V, Shrestha D, Bishnoi A, Chatterjee D, Muthu V, Vinay K. Floppy Eyelid Syndrome. Indian journal of dermatology. 2022 Mar-Apr:67(2):179-181. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_751_21. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36092225]

Aiello F, Gallo Afflitto G, Alessandri Bonetti M, Ceccarelli F, Cesareo M, Nucci C. Lax eyelid condition (LEC) and floppy eyelid syndrome (FES) prevalence in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSA) patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2023 Jun:261(6):1505-1514. doi: 10.1007/s00417-022-05890-5. Epub 2022 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 36380123]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGalindo-Ferreiro A, Zornoff DCM, Correntes JE, Akaishi PM, Schellini SA. Current management of upper lid ptosis: a web-based international survey of oculoplastic surgeons. Arquivos brasileiros de oftalmologia. 2022 Jul 15:86(6):. pii: S0004-27492022005007202. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.2021-0105. Epub 2022 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 35857976]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhodeir J, Ohanian P, Feghali J. Acquired cutis laxa: a clinical review. International journal of dermatology. 2024 Oct:63(10):1334-1356. doi: 10.1111/ijd.17338. Epub 2024 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 38924070]

Skorin L Jr, Norberg S. Orbital Fat Prolapse. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2018 Aug 1:118(8):560. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2018.127. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30073340]

Gniesmer S, Sonntag SR, Schiemenz C, Ranjbar M, Heindl LM, Varde MA, Emmert S, Grisanti S, Kakkassery V. [Diagnosis and treatment of malignant eyelid tumors]. Die Ophthalmologie. 2023 Mar:120(3):262-270. doi: 10.1007/s00347-023-01820-w. Epub 2023 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 36757434]

Sharif MW, Mungara S, Bajaj K, Amador P, Khandelwal N. Orbital Lymphoma Masquerading as Euthyroid Orbitopathy. Cureus. 2023 Feb:15(2):e34885. doi: 10.7759/cureus.34885. Epub 2023 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 36925990]