Introduction

In 2021, the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) Müllerian Anomalies Classification created 9 classifications:

- Cervical agenesis

- Müllerian agenesis

- Unicornuate uterus

- Bicornuate uterus

- Septate uterus

- Uterus didelphys

- Longitucinal vaginal septum

- Transverse vaginal septum

- Complex anomalies [1]

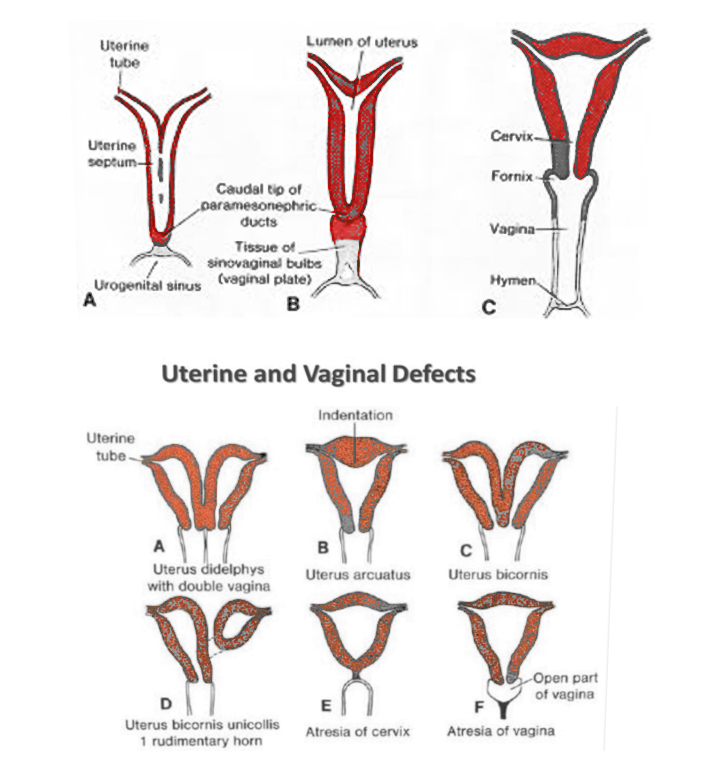

The most common subtype of Müllerian anomalies is the unification defect known as a bicornuate uterus (55.1%-73.5%).[2] A bicornuate uterus arises from incomplete fusion of the paired Müllerian ducts during embryogenesis, typically between the sixth and tenth weeks of gestation. This anomaly results in a uterus with 2 distinct endometrial cavities and a single cervix, although variations exist (see Image. Uterus Embryology).

Clinically, a bicornuate uterus is associated with an increased risk of infertility, recurrent pregnancy loss, preterm labor, malpresentation, and adverse obstetric outcomes. Accurate diagnosis, often requiring advanced imaging modalities such as 3D transvaginal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is essential to differentiate it from other uterine anomalies like a septate uterus, which has markedly different management implications. The risk of severe maternal morbidity for a bicornuate uterus is 3.0%.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

A bicornuate uterus is a uterus with 2 distinct cavities, giving it a heart-shaped appearance rather than the typical pear-shaped appearance.[4] This condition is further classified based on the configuration of the cervix as follows:

- Bicornuate unicollis is characterized by a single cervix. This form results from partial nonfusion of the upper uterine segments while the lower segments, including the cervix, fuse normally.[5]

- Bicornuate bicollis is formed when both the upper and lower uterine segments fail to fuse, leading to a uterus with 2 separate cavities and 2 cervices.[5]

Research has shown that specific genes are involved in the development of the Müllerian ducts. These include Pax, Lim1, Emx2, Wnt4, and Wnt9b, which play a role during the early formation of these structures.[6] Other genes, such as those in the homeobox family and Wnt7a, help guide the development of the Müllerian ducts into specific reproductive organs. For example, Wnt7a helps activate the Hoxa10 and Hoxa11 genes. The Hoxa genes (Hoxa9, 10, 11, and 13) are expressed in specific regions along the ducts, and this pattern is crucial for the formation of the fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, and vagina.[7] Mutations in HOXA13 have been linked to hand-foot-genital syndrome, a condition that causes abnormalities in the limbs and the reproductive tract, including issues with Müllerian duct fusion.

Environmental factors can also contribute to Müllerian duct anomalies. For instance, the development of a T-shaped uterus is attributed to the exposure of diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy, particularly during pregnancies in the 1940s to the 1970s. The incidence of this condition is decreasing as this drug is no longer in use.[8]

Epidemiology

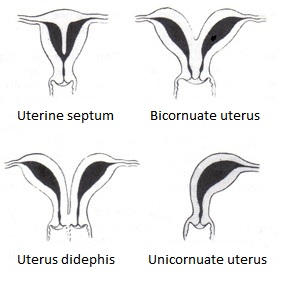

Müllerian anomalies are found in approximately 0.16% to 10% of biological females, with bicornuate uteri accounting for about 37% of these cases (see Image. Types of Bicornuate Uterus Malformation). A review of 94 observational studies examined how common these congenital anomalies are in the general population compared to individuals with a history of infertility or miscarriage. The prevalence of uterine anomalies was 8.0% among those with infertility, 13.3% among those with a history of miscarriage, and 24.5% in individuals with both infertility and miscarriage. In the general population, the most common anomaly is the arcuate uterus. Among those with infertility or miscarriage, the septate uterus is the most frequently identified. The bicornuate uterus occurs in 0.4% of the general population, 1.1% of individuals with infertility, 2.1% of those with miscarriage, and 4.7% of those with both infertility and miscarriage.[9]

Pathophysiology

Two genital ducts lead to the formation of the female genital tract between the sixth and twentieth weeks of gestation. One is the mesonephric duct, also known as the Wolffian duct, and the other is the paramesonephric duct, also referred to as the Müllerian duct. The entire process is divided into three phases.

Phase 1. Morphogenesis: The mesonephric duct begins to form around the sixth week of gestation. In the seventh week, the paramesonephric duct develops as an inward fold (invagination) of the coelomic lining in the upper side of the intermediate cell mass.[10]

Phase 2. Differentiation: The Müllerian ducts on both sides grow downward (caudally) alongside the mesonephric (Wolffian) ducts. They eventually cross over the Wolffian ducts and fuse in the midline at their lower (caudal) ends. The fused central portion becomes the uterus, while the lower fused part forms the upper third of the vagina. The upper (cranial) parts of the Müllerian ducts remain separate and develop into the fallopian tubes.[11]

Phase 3. Resorption of the Septum: By around 12 weeks of gestation, the uterus takes on its basic shape, but the central wall (septum) between the fused Müllerian ducts remains. During this third stage, the septum is gradually resorbed, resulting in a single, unified uterine cavity.[12]

The lower fifth of the vagina has its origin from the endoderm of the urogenital sinus, not the Müllerian ducts. The caudal tip of fused Müllerian tubes is called the Müllerian tubercle. This tubercle interacts with the urogenital sinus and prompts the proliferation of endodermal cells of the urogenital sinus. These are called sinovaginal bulbs, which, along with the uterovaginal canal, form a vaginal plate. This plate canalizes to frame the vaginal canal.[8]

Interference during the second stage of fusion of the Müllerian ducts results in partial fusion of the ducts, leading to the formation of a bicornuate uterus. The outcome of this partial fusion can vary. If the outcome is a solitary vagina yet separate cervices with separate uterine cavities, it is called bicornuate bicollis. However, it is termed bicornuate unicollis uterus when the uterine cavities are discrete, but the cervix and vagina are single.

The origins of the ovaries are from the genital ridge and are independent of the Müllerian ducts. Thus, the ovaries are generally not involved in Müllerian duct anomalies.[13]

Histopathology

It is postulated that the ratio of connective tissue to muscle fibers is abnormal in a uterus with an anomaly. With the growth of the fetus, there may be inadequate uterine volume that leads to increased intrauterine pressure. This increased pressure puts stress on the lower uterus and may lead to cervical incompetence.[14]

History and Physical

A bicornuate uterus can exist as an isolated anomaly or in association with complex uterine and genital malformations. A meta-analysis study of 25 comparative studies reported a significantly increased risk of the following:

- First- and second-trimester pregnancy loss

- Preterm delivery

- Low birth weight babies

- Malpresentation at delivery [15]

Most patients with a bicornuate uterus do not have any symptoms in their adolescence. Still, some may present to the clinic with menorrhagia or dysmenorrhea owing to the presence of 2 uterine cavities. A few are also diagnosed when they present for a routine evaluation during pregnancy. A significant number are diagnosed when they present with obstetric complications. The physical examination of a patient with an isolated uterine anomaly is usually normal.

A longitudinal vaginal septum exists in 25% of cases associated with a bicornuate uterus, which may lead to obstructive symptoms or dyspareunia. The patient may present with leakage of menstrual blood with a tampon in place.[16] The physical exam reveals a vaginal septum, which may be associated with a double cervix and uterus.

Renal anomalies are frequently found in association with Müllerian anomalies due to the interlinked development of the mesonephric and Müllerian ducts with the urogenital sinus. The most common defect is renal agenesis associated with a didelphys uterus. However, renal anomalies can also present along with the bicornuate uterus. An ectopic ureter may also be found.[17]

A patient with a bicornuate uterus with non-communicating uterine cavities, associated with renal agenesis and blind hemivagina, may present with acute urinary retention, pelvic pain, and dysmenorrhea. On physical examination, a bulge can be found in the vagina, making it challenging to explore the cervix.[18]

In another variant, a communicating bicornuate uterus can exist with renal agenesis and a hemivagina. In such cases, patients present with a Gartner duct pseudocyst. On physical examiantion, a cyst is present in the anterolateral wall of the vagina, which indeed is a blind hemivagina. A bicornuate uterus can also exist with a non-communicating uterine horn. Such patients can present with infertility from endometriosis due to retrograde menstruation.[19]

Evaluation

Imaging plays an essential role in the diagnosis and management of a bicornuate uterus. There are multiple modalities available for this purpose, which are as follows:

Hysterosalpingography (HSG) is the most commonly used method to evaluate infertility. During the procedure, contrast is injected through a catheter into the uterine cavity and imaged under fluoroscopy. This procedure allows assessment of the endometrial cavity, fallopian tube patency, and certain Müllerian anomalies. If 2 uterine horns are seen, the intercornual angle is measured; an angle greater than 105 degrees suggests a bicornuate uterus.[20] However, HSG cannot evaluate the external uterine contour, making it unreliable for distinguishing between a septate and bicornuate uterus. Its accuracy is also limited when vaginal or obstructive anomalies are present, as contrast may not reach both cavities, leading to misclassification.[12]

Ultrasound is the primary imaging modality used due to its noninvasive nature and lack of radiation exposure. Two-dimensional (2D) ultrasonography is widely available, while 3-dimensional (3D) ultrasonography offers greater accuracy. Three-dimensional ultrasound has a sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 100% in distinguishing between a bicornuate uterus and a septate uterus. Three-dimensional images are generated from a series of 2D scans, with coronal views being the most valuable. These views allow simultaneous evaluation of the endometrial cavity and external uterine contour, which is essential for differentiating between a bicornuate and septate uterus. The “Z technique” is commonly used to obtain optimal mid-coronal images.[21] Ultrasound should be performed during the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle, when the endometrium is thick and echogenic, enhancing visualization of the uterine contour.[20] To assess for a bicornuate uterus, a line is drawn between the interstitial portions of the fallopian tubes, and a perpendicular line is extended to the point of maximum fundal indentation. If this indentation is greater than 10 mm, it supports the diagnosis of a bicornuate uterus, as proposed by Troiano and McCarthy.[22] An indentation less than 10 mm typically suggests an arcuate or subseptate uterus.[21] Uterine abnormalities visualized by 2D ultrasonography have an accuracy rate of 60% to 82%, whereas 3D ultrasonography has been found to have 88% to 100% accuracy when using a 3D coronal plane that includes external uterine contours and internal uterine contours. A rudimentary horn may be easily missed if it is hidden by the surrounding intestines.[23]

Sonohysterography utilizes a saline infusion in conjunction with ultrasound to visualize the shape and inner lining of the uterine cavity, as well as the uterine surface.[24]

Magnetic resonance imaging is the gold standard for diagnosing a bicornuate uterus because it is noninvasive, does not use radiation, and provides detailed images in multiple planes. It allows evaluation of the entire pelvis, including the uterine fundus, cervix, vagina, and surrounding structures. MRI can accurately distinguish between different types of Müllerian anomalies by assessing the shape and contour of the uterus. A fundal indentation greater than 10 mm suggests a fusion defect, such as a bicornuate or didelphys uterus, while an indentation less than 10 mm indicates a resorption defect, like a septate or arcuate uterus. To differentiate a bicornuate uterus from a didelphys uterus, MRI evaluates the presence of tissue between the 2 horns—myometrial tissue suggests a bicornuate uterus, whereas its absence indicates a didelphys uterus. In cases of a bicornuate bicollis uterus, MRI may reveal a characteristic “owl eyes” appearance due to the presence of two cervices.[25] Although MRI is highly accurate, diagnostic errors are more likely to result from misinterpretation rather than limitations of the imaging itself.[23]

Laparoscopy and hysteroscopy in combination with a simultaneous view of the internal and external uterus remain the gold standard for diagnosing uterine malformations.[24]

Treatment / Management

Management of a bicornuate uterus depends on the patient’s presentation and symptoms. Some patients are diagnosed incidentally during routine prenatal care. In these cases, close prenatal monitoring is recommended due to the increased risk of obstetric complications.[16] Others may present with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss or preterm labor (rate of 18%) [26], which may warrant surgical correction via Strassman metroplasty.[16] First described in 1907, this procedure involves a transverse incision over the uterine fundus, avoiding the uterotubal junctions. The uterine cavity is then opened, the septum is excised, and the 2 horns are unified into a single cavity. The uterus is closed vertically to reduce the risk of intrauterine adhesions.[27](B3)

The laparoscopic approach has recently become the preferred method over traditional abdominal metroplasty due to several advantages, including reduced blood loss, a lower risk of infection, and fewer postoperative adhesions, largely attributed to minimal tissue handling and reduced tissue drying.[28](B2)

A recent multicenter cohort study evaluated a trial of labor after cesarean in patients with a bicornuate uterus and 1 prior low transverse cesarean. While the overall VBAC success rate was high (77.4%), it was lower than in patients with a normal uterus. Rates of uterine rupture were similar, but complications such as placental abruption, retained placenta, NICU admission, and neonatal sepsis were more common in those with a bicornuate uterus.[29](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

When evaluating a suspected bicornuate uterus, establishing an accurate diagnosis is critical, as management and reproductive implications vary significantly among different congenital uterine anomalies. Several conditions can mimic the appearance of a bicornuate uterus on imaging, necessitating a thorough understanding of the differential diagnoses. Accurate differentiation relies on correlating clinical history with advanced imaging techniques, particularly 3D ultrasound and MRI.

- A bicornuate uterus has a longitudinal vaginal septum in some cases, which makes it difficult to differentiate from uterus didelphys. In such cases, the presence of soft tissue between the 2 uterine cavities establishes the diagnosis of a bicornuate uterus.[25]

- It is challenging to distinguish a bicornuate uterus from a septate uterus on hysterosalpingography. The differentiation between bicornuate and septate uteri is critical due to the contrast in their management approaches. A septate uterus is managed via hysteroscopic resection as opposed to a bicornuate uterus, which requires a unification of the uterus. In such a case, MRI helps differentiate fusion anomalies from resorption anomalies.[19]

Prognosis

A bicornuate uterus is associated with adverse reproductive outcomes like preterm labor, recurrent abortions, fetal malpresentation, placental abruption, and cesarean section.[30][31] In a prospective study conducted over 7 years, open Strassman metroplasty was reported to improve fetal viability from 0% to 80%.[32] A case series performed on patients post-laparoscopic metroplasty reported an 85% pregnancy achievement rate. Seven patients with a bicornuate uterus carried the pregnancy from 12 weeks to term. Laparoscopic metroplasty is also associated with a decrease in uterine adhesions and increased uterus compliance, thus decreasing the chances of rupture.[28]

Complications

Patients with a bicornuate uterus can present with several unfortunate complications, including first-trimester miscarriage, preterm birth, and fetal malpresentation.[33] The most prominent complications of pregnancy include small for gestational age infants and stillbirths, which are increased by almost 300% and 250%, respectively. The risks of placental abruption and cesarean delivery are increased by 300% and 500%, respectively.[33]

PPROM, placenta previa, cervical insufficiency, pregnancy-induced HTN, and preeclampsia are also more common with bicornuate uteri. Postpartum hemorrhage, wound complications, hysterectomy, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and blood transfusion are all more common with bicorunate uteri.[33] Latest studies report no decrease in infertility associated with a bicornuate uterus.[33]

In individuals with Müllerian anomalies, an abnormality in uterine artery blood flow velocity has been noted, which may inhibit normal placental formation and development and may be a cause for gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, SGA, and stillbirths. Less functional or a lower quantity of muscle tissue or less efficient contractility could result in uterine atony and explain the increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage.[33]

The most common complication associated with the bicornuate uterus is preterm labor. A cervical length of less than 25 mm on transvaginal ultrasound has a 13 times higher risk of preterm delivery.[34] Cervical cerclage is an effective method to prevent a nonviable preterm delivery in patients with a significantly shortened cervix.[35]

A pregnancy in a bicornuate uterus can also be followed by postpartum hemorrhage. However, surgical approaches, such as Burch or Burch lynch suturing, and conduit ligation can harm the neighboring structures. Moreover, ligation may not be effective with the collateral blood supply of the uterus in pregnancy.[36]

A bicornuate uterus is also a risk factor for rupture of the uterus, even in a primigravida. The explanation could be abnormal development of the lower segment of the uterus or the presence of a fibrous band between the corpora of the uterus. This band restrains the uterus, preventing it from expanding, and thus, the uterus can be more prone to rupture.[37]

Due to the association of uterine anomalies with renal anomalies, a patient is at high risk for gestational hypertension. Therefore, it is crucial to monitor blood pressure during pregnancy in patients with a bicornuate uterus.

Although a bicornuate uterus is not an independent risk factor for endometrial cancer, this cancer can go undetected. If taken from the healthy uterine cavity, an endometrial biopsy can give false-negative results, leading to a delay in diagnosis, which worsens the prognosis for the patient. MRI can play an essential role in diagnosing the disease if a patient with a bicornuate uterus presents with uterine bleeding.[38]

Deterrence and Patient Education

A bicornuate uterus is a rare congenital anomaly, often diagnosed during pregnancy. Patient education is essential to help manage expectations and reduce anxiety. Individuals should be counseled on potential reproductive challenges, including an increased risk of preterm labor, malpresentation, and the possible need for cesarean delivery. Close prenatal monitoring is recommended, and patients should be taught to recognize early signs of preterm labor. While the risk of uterine rupture is low, it should be discussed, especially in those with a prior cesarean. Providing clear, supportive information helps patients make informed decisions and prepares them for a safe pregnancy and delivery.

Pearls and Other Issues

Understanding the nuances of diagnosing and managing a bicornuate uterus requires awareness of key clinical pearls, common pitfalls, preventive strategies, and other important considerations. Misclassification of uterine anomalies can lead to inappropriate management, particularly in reproductive planning and surgical decision-making.

Pearls

- A bicornuate uterus results from incomplete fusion of the Müllerian ducts and is classified as a Class IV Müllerian anomaly.

- It is often discovered incidentally during pregnancy, infertility workup, or imaging for pelvic pain.

- Two endometrial cavities and a single cervix (bicornuate unicollis) or 2 cervices (bicornuate bicollis) may be visualized.

- MRI or 3D transvaginal ultrasound are the imaging modalities of choice for diagnosis.

- It is associated with higher rates of miscarriage, preterm birth, malpresentation, and cesarean delivery.

Disposition

- Most patients with a bicornuate uterus can carry pregnancies, but may require high-risk obstetric care.

- Referral to maternal-fetal medicine may be appropriate during pregnancy.

- If diagnosed outside of pregnancy, counseling about potential reproductive risks and referral to a reproductive endocrinologist may be appropriate.

- Surgical correction (eg, Strassman metroplasty) is rare and reserved for patients with recurrent pregnancy loss linked to the anomaly.

Pitfalls

- Confusing a bicornuate uterus with a septate uterus is a common error. This distinction is important because a septate uterus is surgically correctable, while a bicornuate uterus usually is not.

- Failure to identify the anomaly during imaging or misinterpreting it as a fibroid or uterine mass may delay diagnosis.

- In pregnancy, underestimating the risk of malpresentation or preterm labor can lead to poor outcomes.

Prevention

- There is no known way to prevent a bicornuate uterus, as it is a congenital anomaly.

- Accurate diagnosis and patient education are key to preventing obstetric complications.

- Routine cervical length monitoring may be considered during pregnancy due to the increased risk of preterm birth.

Additional Considerations

- Some people with a bicornuate uterus remain asymptomatic and have expected reproductive outcomes.

- Associated renal anomalies (eg, unilateral renal agenesis) occur in up to 30% of cases, so renal imaging may be warranted.

- Consider psychological support, as patients diagnosed during pregnancy may experience anxiety over potential complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing a bicornuate uterus requires coordinated, interprofessional care to ensure accurate diagnosis, patient-centered counseling, and optimal outcomes. Primary care providers should consider uterine anomalies in adolescents with menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea, prompting early referral.

Differentiation from a septate or didelphic uterus depends on expert imaging by radiologists familiar with embryology. Gynecologists must provide clear education on reproductive risks, supported by nurses and advanced practitioners through ongoing care coordination. Mental health support is essential for patients facing recurrent pregnancy loss. Psychiatrists and behavioral health professionals help address anxiety or depression, while pharmacists ensure safe medication use. Strong team communication enhances patient safety, emotional well-being, and reproductive outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Types of Bicornuate Uterus Malformation. A uterine malformation is a type of female genital malformation resulting from abnormal Müllerian duct(s) development during embryogenesis. The prevalence of uterine malformation is estimated to be 6%-7% in the human female population. They may cause premature birth. Didelphis and bicornuate uterus are the normal anatomy in some mammals, just not in humans.

EternamenteAprendiz, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

References

Pfeifer SM, Attaran M, Goldstein J, Lindheim SR, Petrozza JC, Rackow BW, Siegelman E, Troiano R, Winter T, Zuckerman A, Ramaiah SD. ASRM müllerian anomalies classification 2021. Fertility and sterility. 2021 Nov:116(5):1238-1252. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.09.025. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34756327]

Naeh A, Sigal E, Barda S, Hallak M, Gabbay-Benziv R. The association between congenital uterine anomalies and perinatal outcomes - does type of defect matters? The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2022 Dec:35(25):7406-7411. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2021.1949446. Epub 2021 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 34238096]

Mandelbaum RS, Anderson ZS, Masjedi AD, Violette CJ, McGough AM, Doody KA, Guner JZ, Quinn MM, Paulson RJ, Ouzounian JG, Matsuo K. Obstetric outcomes of women with congenital uterine anomalies in the United States. American journal of obstetrics & gynecology MFM. 2024 Aug:6(8):101396. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2024.101396. Epub 2024 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 38866133]

Alhubaishi L, Alsalihi A, Sharaf A, Khalifa J, Sharaf A. Bicornuate Uterus With a Rudimentary Horn: Management and Considerations. Cureus. 2024 Nov:16(11):e74642. doi: 10.7759/cureus.74642. Epub 2024 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 39735105]

Al Najar MS, Al Ryalat NT, Sadaqah JS, Husami RY, Alzoubi KH. MRI Evaluation of Mullerian Duct Anomalies: Practical Classification by the New ASRM System. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2022:15():2579-2589. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S386936. Epub 2022 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 36388626]

Wilson D, Bordoni B. Embryology, Mullerian Ducts (Paramesonephric Ducts). StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491659]

Roly ZY, Backhouse B, Cutting A, Tan TY, Sinclair AH, Ayers KL, Major AT, Smith CA. The cell biology and molecular genetics of Müllerian duct development. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Developmental biology. 2018 May:7(3):e310. doi: 10.1002/wdev.310. Epub 2018 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 29350886]

Passos IMPE, Britto RL. Diagnosis and treatment of müllerian malformations. Taiwanese journal of obstetrics & gynecology. 2020 Mar:59(2):183-188. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2020.01.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32127135]

Chan YY, Jayaprakasan K, Zamora J, Thornton JG, Raine-Fenning N, Coomarasamy A. The prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies in unselected and high-risk populations: a systematic review. Human reproduction update. 2011 Nov-Dec:17(6):761-71. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr028. Epub 2011 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 21705770]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMoncada-Madrazo M, Rodríguez Valero C. Embryology, Uterus. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31613528]

Rackow BW, Arici A. Reproductive performance of women with müllerian anomalies. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2007 Jun:19(3):229-37 [PubMed PMID: 17495638]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRobbins JB, Broadwell C, Chow LC, Parry JP, Sadowski EA. Müllerian duct anomalies: embryological development, classification, and MRI assessment. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2015 Jan:41(1):1-12. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24771. Epub 2014 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 25288098]

Pizzo A, Laganà AS, Sturlese E, Retto G, Retto A, De Dominici R, Puzzolo D. Mayer-rokitansky-kuster-hauser syndrome: embryology, genetics and clinical and surgical treatment. ISRN obstetrics and gynecology. 2013:2013():628717. doi: 10.1155/2013/628717. Epub 2013 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 23431465]

Latif NFBA, Guan Z, Asare S, Guan X. Robotic-assisted single-site abdominal cerclage in the bicornuate uterus patient with cervical insufficiency. Fertility and sterility. 2024 May:121(5):887-889. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2024.01.036. Epub 2024 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 38316208]

Venetis CA, Papadopoulos SP, Campo R, Gordts S, Tarlatzis BC, Grimbizis GF. Clinical implications of congenital uterine anomalies: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Reproductive biomedicine online. 2014 Dec:29(6):665-83. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.09.006. Epub 2014 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 25444500]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLetterie GS. Management of congenital uterine abnormalities. Reproductive biomedicine online. 2011 Jul:23(1):40-52. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.02.008. Epub 2011 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 21652266]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHall-Craggs MA, Kirkham A, Creighton SM. Renal and urological abnormalities occurring with Mullerian anomalies. Journal of pediatric urology. 2013 Feb:9(1):27-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.11.003. Epub 2011 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 22129802]

Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Obstructive reproductive tract anomalies. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2014 Dec:27(6):396-402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.09.001. Epub 2014 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 25438708]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAcién P, Acién M. Diagnostic imaging and cataloguing of female genital malformations. Insights into imaging. 2016 Oct:7(5):713-26. doi: 10.1007/s13244-016-0515-4. Epub 2016 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 27507534]

Behr SC, Courtier JL, Qayyum A. Imaging of müllerian duct anomalies. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2012 Oct:32(6):E233-50. doi: 10.1148/rg.326125515. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23065173]

Deutch TD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of müllerian duct anomalies: a review of the literature. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2008 Mar:27(3):413-23 [PubMed PMID: 18314520]

Negm SM, Kamel RA, El-Zayat HA, Elbigawy AF, El-Toukhy MM, Amin AH, Nicolaides KH. The value of three-dimensional ultrasound in identifying Mullerian anomalies at risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2022 Aug:35(16):3201-3208. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1815189. Epub 2020 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 32873098]

Qin C, Lee P, Luo L. Comparison between 3D-Enhanced Conventional Pelvic Ultrasound and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Evaluation of Obstructive Müllerian Anomalies and Its Concordance with Surgical Diagnosis. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2025 Apr:38(2):174-179. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2024.07.004. Epub 2024 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 39098548]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCarbonnel M, Pirtea P, de Ziegler D, Ayoubi JM. Uterine factors in recurrent pregnancy losses. Fertility and sterility. 2021 Mar:115(3):538-545. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.12.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33712099]

Yoo RE, Cho JY, Kim SY, Kim SH. A systematic approach to the magnetic resonance imaging-based differential diagnosis of congenital Müllerian duct anomalies and their mimics. Abdominal imaging. 2015 Jan:40(1):192-206. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0195-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25070770]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHughes KM, Kane SC, Haines TP, Sheehan PM. Cervical length surveillance for predicting spontaneous preterm birth in women with uterine anomalies: A cohort study. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2020 Nov:99(11):1519-1526. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13923. Epub 2020 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 32438506]

Strassmann EO. Fertility and unification of double uterus. Fertility and sterility. 1966 Mar-Apr:17(2):165-76 [PubMed PMID: 5907041]

Alborzi S, Asefjah H, Amini M, Vafaei H, Madadi G, Chubak N, Tavana Z. Laparoscopic metroplasty in bicornuate and didelphic uteri: feasibility and outcome. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2015 May:291(5):1167-71. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3520-1. Epub 2014 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 25373708]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRotem R, Hirsch A, Ehrlich Z, Sela HY, Grisaru-Granovsky S, Rottenstreich M. Trial of labor following cesarean in patients with bicornuate uterus: a multicenter retrospective study. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2024 Jul:310(1):253-259. doi: 10.1007/s00404-023-07220-4. Epub 2023 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 37777621]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSutan S, Sabir SA, Liaqat N, Qazi Q. Obstetrical outcome in pregnant women presenting with congenital uterine anomalies. Pakistan journal of medical sciences. 2025 Apr:41(4):1078-1081. doi: 10.12669/pjms.41.4.10793. Epub [PubMed PMID: 40290219]

Kadour Peero E, Badeghiesh A, Baghlaf H, Dahan MH. What type of uterine anomalies had an additional effect on pregnancy outcomes, compared to other uterine anomalies? An evaluation of a large population database. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2022 Dec:35(26):10494-10501. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2022.2130240. Epub 2022 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 36216352]

Rechberger T, Monist M, Bartuzi A. Clinical effectiveness of Strassman operation in the treatment of bicornuate uterus. Ginekologia polska. 2009 Feb:80(2):88-92 [PubMed PMID: 19338203]

Kadour Peero E, Badeghiesh A, Baghlaf H, Dahan MH. How do bicornuate uteri alter pregnancy, intra-partum and neonatal risks? A population based study of more than three million deliveries and more than 6000 bicornuate uteri. Journal of perinatal medicine. 2023 Mar 28:51(3):305-310. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2022-0075. Epub 2022 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 35946504]

Airoldi J, Berghella V, Sehdev H, Ludmir J. Transvaginal ultrasonography of the cervix to predict preterm birth in women with uterine anomalies. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2005 Sep:106(3):553-6 [PubMed PMID: 16135586]

Yassaee F, Mostafaee L. The role of cervical cerclage in pregnancy outcome in women with uterine anomaly. Journal of reproduction & infertility. 2011 Oct:12(4):277-9 [PubMed PMID: 23926514]

Abraham C. Bakri balloon placement in the successful management of postpartum hemorrhage in a bicornuate uterus: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2017:31():218-220. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.01.055. Epub 2017 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 28189983]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNitzsche B, Dwiggins M, Catt S. Uterine rupture in a primigravid patient with an unscarred bicornuate uterus at term. Case reports in women's health. 2017 Jul:15():1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.crwh.2017.03.004. Epub 2017 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 29593991]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGao J, Zhang J, Tian W, Teng F, Zhang H, Zhang X, Wang Y, Xue F. Endometrial cancer with congenital uterine anomalies: 3 case reports and a literature review. Cancer biology & therapy. 2017 Mar 4:18(3):123-131. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2017.1281495. Epub 2017 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 28118070]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence