Introduction

Arytenoid subluxation is a rare but clinically significant complication of airway manipulation, capable of causing persistent voice changes and functional impairment. The condition involves partial displacement of the arytenoid cartilage within the cricoarytenoid joint. This entity is distinct from complete arytenoid dislocation, which entails total separation of the cartilaginous surfaces.[1] Although the terms "subluxation" and "dislocation" are often used interchangeably in clinical practice, precise differentiation is essential for diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning.[2]

Contemporary evidence suggests that arytenoid subluxation may be more common than previously recognized. Recent data indicate a pooled incidence of 0.093% (confidence interval: 0.045-0.14%) among patients undergoing endotracheal intubation. This update reflects both improved diagnostic techniques and heightened clinical awareness. The discrepancy between historical and contemporary incidence rates likely results from underdiagnosis due to confusion with vocal fold immobility from other causes, such as recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) paralysis.[3][4]

Recent advances in diagnostic imaging, particularly dynamic computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography, have enhanced the ability to diagnose and characterize arytenoid subluxation accurately.[5][6] Treatment strategies have evolved, with evidence supporting early intervention and specific techniques that optimize patient outcomes.[7]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Arytenoid subluxation is multifactorial, with endotracheal intubation representing the most common precipitating factor in contemporary practice.[8][9] Risk factors may be categorized as procedure- or patient-related. Procedure-associated factors include improper endotracheal tube insertion, difficult intubation requiring multiple attempts, prolonged intubation, use of specific airway devices such as bougies, blind intubation techniques, insertion of large-bore double-lumen tubes, head and neck movement during intubation, and the experience level of the intubating physician.[10][11] Patient-specific factors include younger age, female sex, taller stature, and higher body mass index (BMI).[12] The use of a stylet during intubation is protective, associated with a reduced risk of arytenoid dislocation.[13]

Abdominal surgery accounts for a disproportionate number of cases, with a study reporting that 88.1% of arytenoid dislocation cases followed major abdominal procedures. Cardiovascular surgery has also emerged as a significant risk factor, with a large retrospective study demonstrating an odds ratio of 9.9 for arytenoid dislocation.[14] Head and neck positioning during surgery is a particularly important and modifiable risk factor, with an incidence rate ratio of 3.10 for arytenoid subluxation. The experience level of the intubating physician is a significant determinant, with 1st-year anesthesia residents demonstrating an incidence rate ratio of 2.30 compared to more experienced practitioners.[15]

External laryngeal trauma constitutes the 2nd most common etiology of arytenoid subluxation, although it accounts for a substantially smaller proportion of cases than iatrogenic injury.[16] Less frequent causes include severe coughing, the use of laryngeal mask airways, and rare instances of spontaneous subluxation.[17][18][17] Although laryngeal mask airways are traditionally considered safer than endotracheal intubation, their use has been associated with occasional cases of arytenoid dislocation, indicating that even supraglottic airway devices can produce laryngeal injury under specific circumstances.[19]

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of arytenoid subluxation has been clarified through recent systematic reviews and large-scale studies.[20] Contemporary meta-analysis data indicate a pooled incidence of 0.093% (confidence interval: 0.045%-0.14%) among patients undergoing endotracheal intubation, representing a substantial update from earlier estimates suggesting rates as low as 0.009%. This discrepancy likely reflects improved diagnostic awareness and more sophisticated detection methods rather than an actual increase in incidence.

Demographic patterns demonstrate consistent trends across multiple studies. Female sex is a significant risk factor, with incidence rate ratios of 3.05. Younger age is associated with increased risk in some analyses. BMI has emerged as an independent epidemiological factor, with higher BMI correlating with elevated risk. A dedicated case-control study confirmed BMI as an independent risk factor with statistical significance (P = 0.025).

Geographic and institutional variations indicate that factors beyond patient demographics influence occurrence. Institutions performing high volumes of complex procedures, particularly cardiovascular and major abdominal operations, report higher rates of arytenoid subluxation. Temporal patterns suggest a higher incidence when less experienced residents perform intubations. International differences likely reflect variations in diagnostic practices, reporting systems, and clinical awareness rather than true population differences.

Pathophysiology

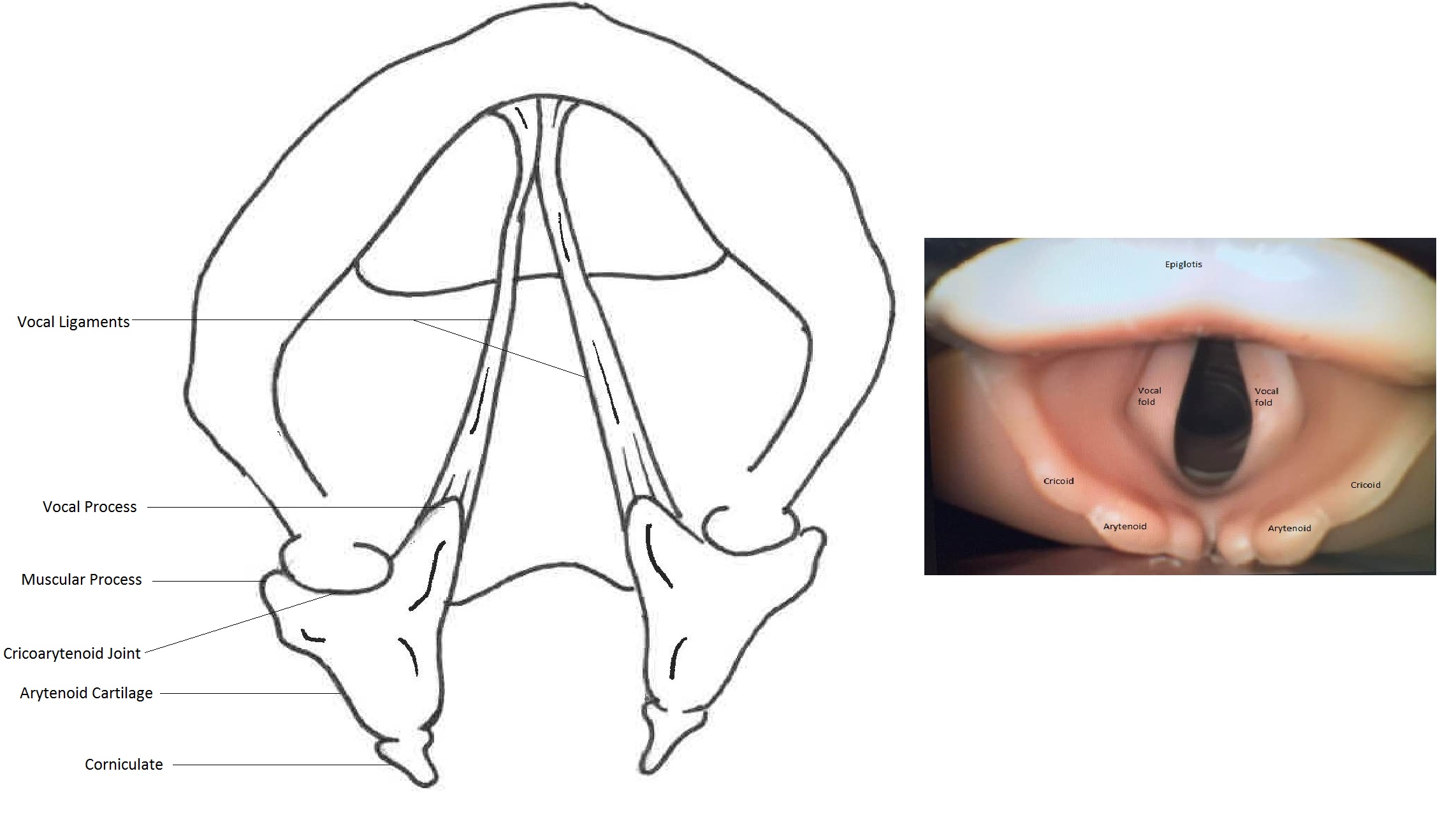

The pathophysiology of arytenoid subluxation involves disruption of normal anatomical relationships within the cricoarytenoid joint, resulting in altered laryngeal function and impaired voice production (see Image. Anatomy of the Laryngeal Cartilages and Vocal Folds).[21] The cricoarytenoid joint is a synovial articulation between the base of the arytenoid cartilage and the superior surface of the cricoid cartilage lamina, permitting complex 3-dimensional movements essential for vocal fold positioning during respiration, phonation, and airway protection.[22] The joint capsule is reinforced by ligaments, including the posterior cricoarytenoid and vocal ligaments, which provide stability while allowing physiological mobility.[23]

Arytenoid subluxation typically occurs when external forces exceed the joint’s normal range of motion or stability limits. During endotracheal intubation, factors contributing to excessive force include direct instrument contact with the arytenoid cartilage, forceful manipulation during difficult intubation, and suboptimal head and neck positioning.[24] Traumatic extubation with a partially inflated cuff can produce posterolateral arytenoid displacement, as the inflated cuff may engage laryngeal structures during removal.

A cascade of secondary pathophysiological changes may occur following the initial injury. Hemarthrosis with subsequent fibrosis and RLN paresis can develop after the primary insult.[25] Joint inflammation may progress to cricoarytenoid joint ankylosis, resulting in permanent arytenoid fixation and irreversible functional impairment if not addressed promptly.

Dynamic CT studies demonstrate significant differences in bilateral vocal cord height and laryngeal chamber area between patients with arytenoid dislocation and healthy controls, with structural characteristics evolving as the condition progresses. Understanding these pathophysiological mechanisms has important implications for prevention and treatment, highlighting the importance of early closed reduction techniques to restore normal joint anatomy before fibrotic changes become established.

History and Physical

Arytenoid subluxation typically presents within hours of the precipitating event, most commonly endotracheal intubation or laryngeal trauma. Voice changes vary according to the severity and type of displacement, ranging from mild hoarseness to complete aphonia. The most frequently reported symptoms include persistent hoarseness, breathy voice quality, vocal fatigue, and markedly reduced vocal projection. A systematic review reported dysphonia in 27% of cases with laryngeal injury.

The temporal relationship between the inciting event and symptom onset is critical for diagnosis, as voice changes typically persist beyond the expected duration of routine postintubation hoarseness. Dysphagia and odynophagia are common, with difficulty swallowing liquids more pronounced than solids and sensations of food sticking in the throat. Pain occurs in 38% of patients and may localize to the throat or radiate to the ears, often exacerbated by swallowing or phonation. Coughing affects 32% of patients and may result from aspiration, laryngeal irritation, or altered sensory feedback mechanisms.

Physical examination should include a comprehensive head and neck assessment, with focused evaluation of laryngeal tenderness, asymmetry, or crepitus. Direct laryngoscopy or flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy reveals the hallmark finding of arytenoid malposition, typically presenting as anterior and medial displacement in anterior subluxation. In anteromedial dislocation, the affected vocal fold appears shortened and bowed, whereas posterolateral dislocation produces a straightened and lengthened vocal fold. The absence of the "jostle sign," defined as displacement of an immobile arytenoid by the mobile contralateral arytenoid during phonation, distinguishes arytenoid subluxation from vocal fold paralysis.

Videostroboscopy provides additional diagnostic information. Asymmetric vocal fold vibration, altered mucosal wave patterns, and differences in vocal fold tension are commonly observed using this technique.[26]

Evaluation

Accurate diagnosis of arytenoid subluxation requires a multimodal approach integrating clinical assessment with imaging studies and specialized testing. Diagnostic evaluation must differentiate arytenoid subluxation from other causes of vocal fold immobility, particularly RLN paralysis, which can present with similar findings. Flexible laryngoscopy serves as the initial diagnostic tool, allowing direct visualization of laryngeal structures and assessment of vocal fold mobility. However, laryngoscopy alone is insufficient to distinguish mechanical dislocation from nerve injury.

Key laryngoscopic findings suggestive of arytenoid subluxation include asymmetric arytenoid positioning, altered vocal fold length and tension, and absence of the "jostle sign" during phonation. High-resolution CT provides detailed anatomical information regarding arytenoid cartilage position and cricoarytenoid joint integrity. Dynamic CT allows quantitative evaluation of laryngeal structural changes throughout respiratory and phonatory cycles. Bedside ultrasound offers a noninvasive method to assess cricoarytenoid joint position and motion in real time.

Laryngeal electromyography differentiates mechanical dislocation from RLN paralysis, with normal muscle activity observed in dislocation and characteristic denervation changes in nerve injury. Quantitative movement analysis using vector-based measurement reveals greater arytenoid mobility in dislocation compared to paralysis.[27] Voice assessment should combine subjective and objective methods, including acoustic analysis and patient-reported outcome measures, to characterize functional impact.

Treatment / Management

The primary treatment for arytenoid subluxation is closed reduction, which entails manual repositioning of the displaced arytenoid cartilage under direct laryngoscopic visualization. Recent meta-analysis data report success rates of 77% (confidence interval: 62%-87%) under general anesthesia and 89% (confidence interval: 70%-97%) under local anesthesia. These findings suggest that regional anesthesia may improve outcomes, potentially by enhancing patient cooperation, minimizing tissue trauma, and allowing intraoperative assessment of voice quality.

The timing of intervention is a critical determinant of treatment success. Evidence indicates that closed reduction performed within 21 days of the presumed dislocation consistently produces superior outcomes. Recent innovations include modified laryngeal forceps, which reduce treatment duration compared to traditional instruments, with a median time to return of normal voice of 17.92 days (standard deviation: 3.83 days) versus 31.08 days (standard deviation: 10.56 days) using conventional forceps.

Voice therapy can serve as an adjunct to closed reduction or, in selected cases, as primary treatment.[28] A recent study demonstrated that combining voice therapy with closed reduction under local anesthesia produced superior outcomes compared to closed reduction alone, with significant improvements in acoustic parameters and patient-reported outcomes. Conservative management with voice therapy alone has been reported successfully in select patients, particularly older adults or people with significant comorbidities.

Botulinum toxin injection may be employed as an adjunct, especially in anteromedial dislocation, where adductor muscle forces contribute to persistent arytenoid displacement.[29] Management of failed primary reduction requires evaluation of the interval since the initial injury, the extent of fibrosis, and patient-specific factors influencing the likelihood of success with repeat intervention.

Differential Diagnosis

The primary differential diagnosis for arytenoid subluxation is unilateral vocal fold paralysis due to RLN injury, as both conditions present with similar voice changes and apparent vocal fold immobility on laryngoscopy. Accurate differentiation is essential because treatment strategies differ. Arytenoid subluxation requires mechanical reduction, whereas vocal fold paralysis may necessitate voice therapy, injection laryngoplasty, or medialization procedures.

Several features aid distinction between the 2 conditions. In arytenoid subluxation, the vocal fold typically retains restricted and asymmetric movement, whereas complete nerve paralysis produces an immobile vocal fold. Direct visualization reveals malposition of the arytenoid cartilage, with anterior and medial displacement in anteromedial dislocation or posterior and lateral displacement in posterolateral cases. The "jostle sign" is typically present in vocal fold paralysis but absent in arytenoid subluxation.

Laryngeal electromyography provides definitive differentiation between mechanical and neurological causes of vocal fold immobility. Pure arytenoid subluxation demonstrates normal muscle activity and innervation, whereas RLN injury produces characteristic denervation changes, including fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves, and reduced recruitment. Quantitative movement analysis using vector-based assessment of arytenoid motion during respiration has emerged as a novel diagnostic tool, demonstrating significantly greater cuneiform movement in dislocation compared to paralysis. Other differential diagnoses include vocal fold scarring, posterior glottic stenosis, cricoarytenoid joint arthritis, laryngeal edema, vocal fold hemorrhage, laryngeal fractures, functional voice disorders, and laryngeal neoplasms.

Prognosis

Prognosis for arytenoid subluxation depends primarily on the timing of diagnosis and intervention, with early recognition and prompt treatment associated with excellent outcomes and complete restoration of voice function. Meta-analysis evidence indicates that timing significantly influences results, with intervention within the first few weeks after injury producing complete or near-complete recovery of voice and restoration of arytenoid mobility. Contemporary case series report favorable outcomes when treatment is provided promptly. In a prospective study of 22 consecutive patients, 86% demonstrated recovery of arytenoid motion accompanied by concomitant voice improvement following closed reduction.

Treatment outcomes may be categorized using multidimensional evaluation criteria. A study of 57 patients classified results as "recovered" (42%), "improved" (26%), and "ineffective" (32%). The use of modified laryngeal forceps is associated with faster recovery and superior outcomes compared to traditional instruments. Long-term prognosis remains excellent for patients receiving successful reduction within the optimal time window, with sustained improvement in voice and arytenoid mobility. Delayed intervention beyond several weeks is associated with reduced recovery due to fibrosis and joint stiffening.

Complications

The most significant complication of untreated arytenoid subluxation is permanent voice impairment resulting from chronic arytenoid malposition and subsequent fibrosis of the cricoarytenoid joint. Cricoarytenoid joint ankylosis represents the most serious long-term consequence, characterized by permanent fixation of the arytenoid cartilage due to intra-articular fibrosis and scarring. Aspiration risk constitutes an important complication, particularly in the acute phase when glottal closure is compromised by arytenoid malposition.

Secondary pathophysiological changes may include hemarthrosis, fibrosis, and RLN paresis. Failed reduction attempts increase scarring and reduce the likelihood of success with subsequent interventions. Additional complications include psychological effects related to voice dysfunction, recurrence following successful reduction, bilateral arytenoid subluxation with potential airway compromise, chronic pain syndromes, and development of compensatory voice behaviors that may persist despite successful treatment.[30]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Following successful closed reduction of arytenoid subluxation, patients require careful monitoring for recurrence of displacement and systematic assessment of voice recovery. The immediate postoperative period typically involves voice rest for 24 to 48 hours to minimize stress on the repositioned joint. Prolonged voice rest beyond this period is generally not recommended, as it may contribute to muscle weakness and delayed functional recovery.

Voice therapy evaluation and intervention are beneficial for optimizing vocal function and addressing residual voice changes. Studies demonstrate that combining voice therapy with closed reduction produces superior outcomes compared to reduction alone. Follow-up laryngoscopy is typically performed within 1 to 2 weeks postreduction to assess arytenoid position and vocal fold mobility, with additional examinations scheduled according to symptoms and recovery progress.

Patient education is essential in postoperative care. Instructions should include voice use guidelines, warning signs warranting immediate evaluation, and realistic expectations for recovery. Although activity restrictions are generally minimal, patients should avoid activities that markedly increase intrathoracic pressure during the first few weeks.

Consultations

Otolaryngology consultation is essential for the diagnosis, confirmation, and treatment of arytenoid subluxation, as management requires specialized expertise in laryngeal anatomy and surgical techniques. Speech-language pathologists provide expertise in voice assessment and therapy, particularly for patients who have persistent voice changes following treatment or are suitable for conservative management.

Anesthesiology input may be beneficial for perioperative management, especially in patients with a history of difficult airway management or arytenoid subluxation during challenging intubation. Additional consultations may include pulmonology for respiratory complications like aspiration pneumonia, gastroenterology for significant swallowing dysfunction, pain management for chronic pain syndromes, and physical therapy for secondary muscle tension patterns.

Psychology or psychiatry may be involved for substantial psychological impacts, and occupational medicine may address workplace-related factors. Interprofessional team meetings are recommended for complex cases to optimize patient outcomes.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education should emphasize the importance of early recognition of voice changes following intubation or laryngeal trauma, as prompt diagnosis and treatment are critical for optimal outcomes. Patients should seek immediate medical attention if persistent hoarseness, voice changes, or swallowing difficulties occur after procedures involving airway manipulation. Education should highlight that symptoms persisting beyond 48 to 72 hours warrant further evaluation.

Healthcare provider education constitutes a key component of prevention and early recognition strategies. Clinicians involved in airway management, including anesthesiologists, emergency physicians, and intensivists, require training on risk factors and the importance of gentle technique during intubation and extubation. Prevention strategies should target modifiable factors, including stylet use during intubation, careful head and neck positioning, and ensuring adequate anesthesia depth and muscle relaxation prior to intubation attempts.

Institutional quality improvement initiatives should address system-level factors, including standardized intubation protocols, supervision requirements for trainees, availability of difficult airway equipment, and systematic postintubation complication surveillance. Professional voice users require specialized education regarding voice care and injury prevention.[31]

Pearls and Other Issues

Early recognition is essential for optimal outcomes in arytenoid subluxation. Healthcare providers must maintain a high index of suspicion in patients exhibiting voice changes following intubation. Persistence of voice symptoms beyond 48 to 72 hours after airway manipulation should prompt evaluation for arytenoid subluxation, particularly in patients with identified risk factors. Delayed diagnosis and intervention substantially compromise outcomes due to the development of fibrosis and joint stiffening.

Stylet use during intubation is protective against arytenoid dislocation and should be incorporated into routine practice. Modified laryngeal forceps offer advantages over traditional instruments for closed reduction, with studies demonstrating faster recovery times. Local anesthesia appears superior to general anesthesia for closed reduction, with meta-analysis data reporting success rates of 89% versus 77%, respectively. Combining voice therapy with closed reduction may produce superior outcomes compared to reduction alone.

Quantitative movement analysis using vector assessment represents an emerging diagnostic tool that can enhance differentiation between arytenoid subluxation and vocal fold paralysis. Dynamic CT imaging provides advanced diagnostic capabilities, particularly in complex cases. Cardiovascular surgery is a notable risk factor, with odds ratios approaching 10 in large studies. Pediatric cases may present with more subtle symptoms than adults, necessitating heightened vigilance for accurate diagnosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Optimal management of arytenoid subluxation requires coordinated care among multiple healthcare disciplines, with anesthesiologists, otolaryngologists, and speech-language pathologists fulfilling key roles in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Early recognition by anesthesia providers, prompt consultation with otolaryngology, and appropriate timing of intervention are critical determinants of successful outcomes. Standardized protocols and clear communication pathways between specialties have substantially improved patient care.

Anesthesiologists play a pivotal role in prevention and early recognition by employing appropriate intubation techniques, maintaining careful head and neck positioning, and considering protective measures such as stylet use during intubation. Otolaryngologists provide essential expertise in diagnosis, confirmation, and treatment, requiring familiarity with diagnostic criteria, imaging requirements, and intervention options. Speech-language pathologists contribute specialized knowledge in voice assessment and therapy, enhancing both diagnostic accuracy and functional outcomes.

Quality improvement initiatives should adopt systematic approaches to prevention, early recognition, and treatment optimization, including regular case review, analysis of contributing factors, and implementation of evidence-based strategies. Education and training programs should address discipline-specific knowledge and skills, with simulation-based training particularly valuable for developing technical proficiency and improving interprofessional communication in managing this rare but clinically significant complication.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Anatomy of the Laryngeal Cartilages and Vocal Folds. This figure shows a diagram (left) and an endoscopic image (right) illustrating the cricoarytenoid joint, arytenoid cartilage, vocal folds, and surrounding laryngeal structures from a superior view. Both images depict normal anatomy without pathological findings.

Illustration contributed by Mayank Mehrotra, MD and Picture of laryngeal anatomy of bronchoscopy model contributed by Rafael Lombardi, MD

References

Alalyani NS, Alhedaithy AA, Alshammari HK, AlHajress RI, Alelyani RH, Alshammari MF, Alhalafi AH, Alharbi A, Aldabal N. Incidence and Risk Factors of Arytenoid Dislocation Following Endotracheal Intubation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2024 Aug:16(8):e67917. doi: 10.7759/cureus.67917. Epub 2024 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 39328702]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFrosolini A, Caragli V, Badin G, Franz L, Bartolotta P, Lovato A, Vedovelli L, Genovese E, de Filippis C, Marioni G. Optimal Timing and Treatment Modalities of Arytenoid Dislocation and Subluxation: A Meta-Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2025 Jan 8:61(1):. doi: 10.3390/medicina61010092. Epub 2025 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 39859074]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChen M, Yu T, Cui X, Wang X. Risk factors for the occurrence of arytenoid dislocation after major abdominal surgery: A retrospective study. Medicine. 2024 Nov 22:103(47):e40593. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000040593. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39809151]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNorris BK, Schweinfurth JM. Arytenoid dislocation: An analysis of the contemporary literature. The Laryngoscope. 2011 Jan:121(1):142-6. doi: 10.1002/lary.21276. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21181984]

Jin J, Xing L, Wang Y, Zhuang P. Using Dynamic CT to Explore the Effect of Disease Course on Arytenoid Dislocation. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2024 Nov 14:():. pii: S0892-1997(24)00176-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2024.06.004. Epub 2024 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 39547827]

Kunieda C, Mori T, Konomi U, Matsushima K, Komazawa D, Kanazawa T. Ultrasonography of the cricoarytenoid joint and its movements. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2024 Dec:51(6):1068-1072. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2024.10.001. Epub 2024 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 39509941]

Lou Z, Li X, Jiang JJ, Lin Z. Modified Laryngeal Forceps for Arytenoid Cartilage Dislocation Caused by Endotracheal Intubation: A Retrospective Case-Control Pilot Study. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2023 Oct 16:():1455613231205529. doi: 10.1177/01455613231205529. Epub 2023 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 37840263]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLee SW, Park KN, Welham NV. Clinical features and surgical outcomes following closed reduction of arytenoid dislocation. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2014 Nov:140(11):1045-50. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.2060. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25257336]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLee DH, Yoon TM, Lee JK, Lim SC. Clinical Characteristics of Arytenoid Dislocation After Endotracheal Intubation. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2015 Jun:26(4):1358-60. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001749. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26080195]

Davis L, Cook-Sather SD, Schreiner MS. Lighted stylet tracheal intubation: a review. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2000 Mar:90(3):745-56 [PubMed PMID: 10702469]

Mikuni I, Suzuki A, Takahata O, Fujita S, Otomo S, Iwasaki H. Arytenoid cartilage dislocation caused by a double-lumen endobronchial tube. British journal of anaesthesia. 2006 Jan:96(1):136-8 [PubMed PMID: 16311281]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLou Z, Yu X, Li Y, Duan H, Zhang P, Lin Z. BMI May Be the Risk Factor for Arytenoid Dislocation Caused by Endotracheal Intubation: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2018 Mar:32(2):221-225. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.05.010. Epub 2017 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 28601417]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWu L, Shen L, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Huang Y. Association between the use of a stylet in endotracheal intubation and postoperative arytenoid dislocation: a case-control study. BMC anesthesiology. 2018 May 31:18(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0521-9. Epub 2018 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 29855263]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTsuru S, Wakimoto M, Iritakenishi T, Ogawa M, Hayashi Y. Cardiovascular operation: A significant risk factor of arytenoid cartilage dislocation/subluxation after anesthesia. Annals of cardiac anaesthesia. 2017 Jul-Sep:20(3):309-312. doi: 10.4103/aca.ACA_71_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28701595]

Jang EA, Yoo KY, Lee S, Song SW, Jung E, Kim J, Bae HB. Head-neck movement may predispose to the development of arytenoid dislocation in the intubated patient: a 5-year retrospective single-center study. BMC anesthesiology. 2021 Jul 31:21(1):198. doi: 10.1186/s12871-021-01419-1. Epub 2021 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 34330223]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFriedlander E, Pascual PM, Da Costa Belisario J, Serafini DP. Subluxation of the Cricoarytenoid Joint After External Laryngeal Trauma: A Rare Case and Review of the Literature. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2017 Mar:69(1):130-132. doi: 10.1007/s12070-016-1028-7. Epub 2016 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 28239594]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCho R, Zamora F, Dincer HE. Anteromedial Arytenoid Subluxation Due to Severe Cough. Journal of bronchology & interventional pulmonology. 2018 Jan:25(1):57-59. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000403. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28926355]

Okazaki Y, Ichiba T, Higashi Y. Unusual cause of hoarseness: Arytenoid cartilage dislocation without a traumatic event. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2018 Jan:36(1):172.e1-172.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.10.041. Epub 2017 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 29066184]

Xing L, Ding Y, Zhou Y, Yu L, Gao R, Gu L. A case of arytenoid dislocation after ProSeal laryngeal mask airway insertion: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2024 Nov:124():110372. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2024.110372. Epub 2024 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 39353315]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrodsky MB, Akst LM, Jedlanek E, Pandian V, Blackford B, Price C, Cole G, Mendez-Tellez PA, Hillel AT, Best SR, Levy MJ. Laryngeal Injury and Upper Airway Symptoms After Endotracheal Intubation During Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2021 Apr 1:132(4):1023-1032. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005276. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33196479]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRubin AD, Hawkshaw MJ, Moyer CA, Dean CM, Sataloff RT. Arytenoid cartilage dislocation: a 20-year experience. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2005 Dec:19(4):687-701 [PubMed PMID: 16301111]

Allen E, Minutello K, Jozsa F, Murcek BW. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Larynx Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261997]

Andaloro C, Sharma P, La Mantia I. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Larynx Arytenoid Cartilage. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020624]

Tolley NS, Cheesman TD, Morgan D, Brookes GB. Dislocated arytenoid: an intubation-induced injury. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1990 Nov:72(6):353-6 [PubMed PMID: 2241051]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTan V, Seevanayagam S. Arytenoid subluxation after a difficult intubation treated successfully with voice therapy. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 2009 Sep:37(5):843-6 [PubMed PMID: 19775054]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWu X, Mao W, Zhang J, Wei C. Treatment Outcomes of Arytenoid Dislocation by Closed Reduction: A Multidimensional Evaluation. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2021 May:35(3):463-467. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2019.10.010. Epub 2019 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 31734016]

Zhuang P, Nemcek S, Surender K, Hoffman MR, Zhang F, Chapin WJ, Jiang JJ. Differentiating arytenoid dislocation and recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis by arytenoid movement in laryngoscopic video. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2013 Sep:149(3):451-6. doi: 10.1177/0194599813491222. Epub 2013 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 23719396]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWang S, Du J, Gao X, Huang Y, Zhang L, Fu D. The Application and Efficacy of Voice Therapy and Closed Reduction Under Local Anesthesia Combination for Arytenoid Dislocation. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2024 Oct 25:():. pii: S0892-1997(24)00346-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2024.10.002. Epub 2024 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 39490339]

Rontal E, Rontal M. Botulinum toxin as an adjunct for the treatment of acute anteromedial arytenoid dislocation. The Laryngoscope. 1999 Jan:109(1):164-6 [PubMed PMID: 9917060]

Yan W, Dong W, Chen Z. Prolonged Tracheal Intubation in the ICU as a Possible Risk Factor for Arytenoid Dislocation After Liver Transplant Surgery: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Annals of transplantation. 2023 Oct 10:28():e940727. doi: 10.12659/AOT.940727. Epub 2023 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 37814440]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMallon AS, Portnoy JE, Landrum T, Sataloff RT. Pediatric arytenoid dislocation: diagnosis and treatment. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2014 Jan:28(1):115-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2013.08.016. Epub 2013 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 24119642]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence