Introduction

Unstable angina falls under the umbrella term "acute coronary syndrome" (ACS). ACS affects a large portion of the population and remains the leading cause of death worldwide.[1] Distinguishing unstable angina from other causes of chest pain, including stable angina, guides treatment decisions and patient disposition. Clinicians must recognize the signs and symptoms of ACS, as patients depend on healthcare professionals to differentiate this condition from noncardiac chest pain.[2] Although patients frequently present to the emergency department, ACS can also manifest in the outpatient setting. Extensive research has identified effective treatment modalities and diagnostic tools essential for managing unstable angina and other ACS variants.[3][4][5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

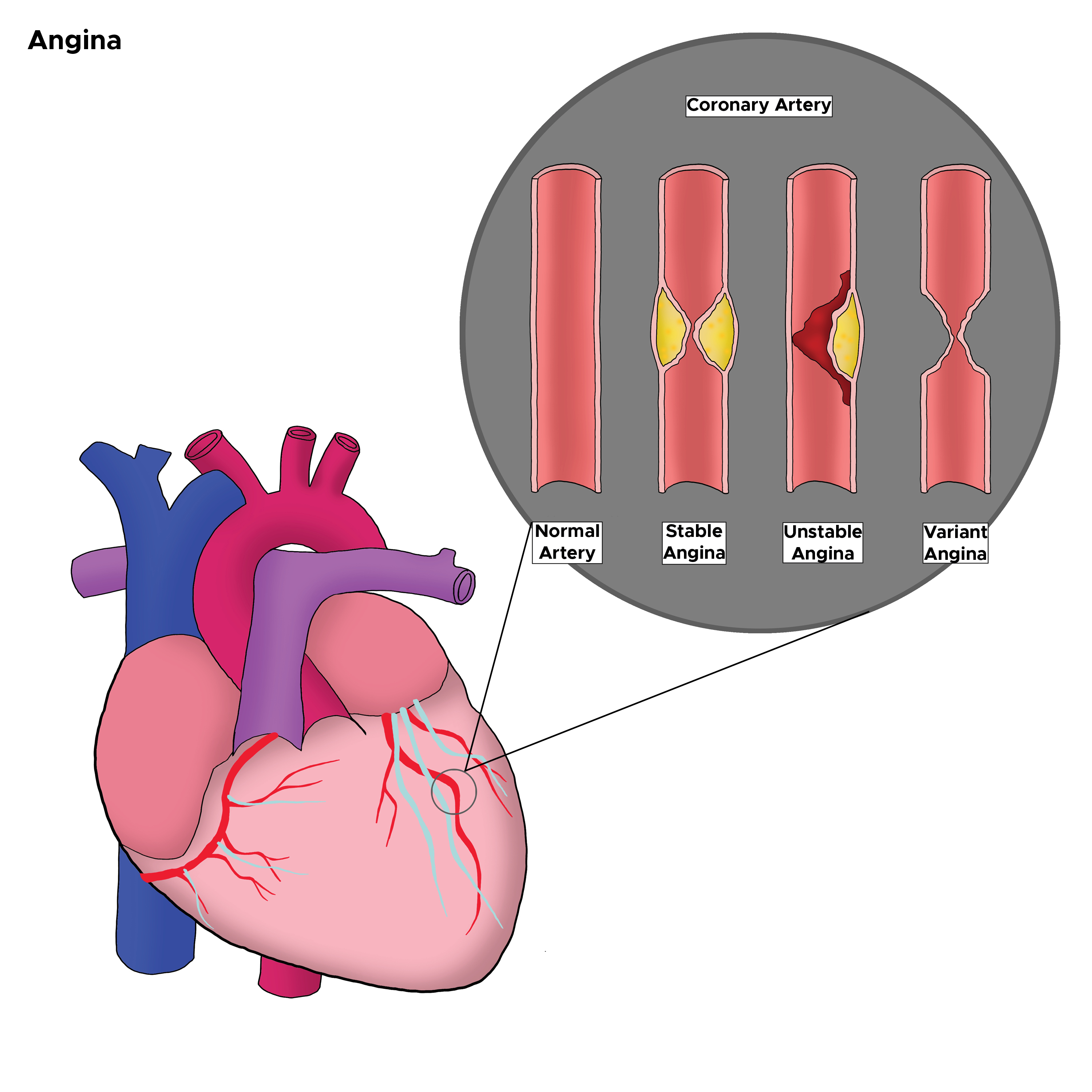

Coronary atherosclerotic disease underlies unstable angina in nearly all patients with acute myocardial ischemia. The primary cause of unstable angina involves coronary artery narrowing due to a nonocclusive thrombus forming on a disrupted atherosclerotic plaque.[6] A less common cause is coronary artery vasospasm, as seen in variant Prinzmetal angina. Endothelial or vascular smooth muscle dysfunction triggers this vasospasm (see Image. Coronary Artery Changes and Corresponding Types of Angina).[7]

Epidemiology

Despite significant advancements in diagnosing and treating ACS, cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide, with ischemic heart disease accounting for 50% of these fatalities.[8] Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases contribute to 12% of the global annual loss in disability-adjusted life years.[9] Notable global variations exist in rates of revascularization and long-term mortality following ACS.[10][11]

Coronary artery disease (CAD) represents the most common form of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and caused approximately 371,506 deaths in 2022; adults younger than 65 accounted for 20% of cardiovascular disease deaths in the same year. Among adults aged 20 and older, 1 in 20 has CAD. Every 40 seconds, 1 person in the United States (US) experiences a heart attack. (Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024) CAD causes over a third of the deaths in individuals aged 35 and older, representing the leading cause of mortality in this age group.

Furthermore, approximately 18 million individuals in the US live with CAD. The incidence is higher in men but converges between men and women after the age of 75. Additional risk factors include the following:

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- High cholesterol

- Tobacco use (smoking history)

- Cocaine or amphetamine abuse

- Family history of cardiovascular disease

- Chronic kidney disease

- Human immunodeficiency virus infection

- Autoimmune disorders

- Anemia [12]

The mean age at presentation is 62 years, with women presenting at older ages than men, while Black individuals tend to present at a younger age. Heart disease accounted for 17.4% of all deaths in 2021. Among racial and ethnic groups, Black non-Hispanic individuals had the highest proportion at 22.6%, while Hispanic individuals had the lowest at 11.9%. Advancements in ACS management over the past 20 years have contributed to significant reductions in age-standardized mortality rates in higher-income regions such as North America, Europe, and Oceania, compared to persistently higher rates in lower-income areas, including Latin America, Asia, and the Caribbean.[13]

Pathophysiology

Unstable angina occurs when blood flow to the myocardium is obstructed, leading to inadequate perfusion.[14] Blood supply to the heart begins in the aorta and flows into the coronary arteries, which branch into smaller vessels to nourish specific areas of the myocardium. The left coronary artery divides into the circumflex and left anterior descending arteries, while the right coronary artery splits into smaller branches. Symptoms of angina develop when increased oxygen demand coincides with reduced coronary flow reserve, primarily caused by vessel lumen obstruction due to atherosclerotic coronary plaque or decreased oxygen supply. Some patients without significant coronary lesions on angiography may have anomalies in coronary circulation, coronary microvascular dysfunction, or vasospasm.[15]

Unstable angina typically results from the disruption of intraluminal plaque, leading to the formation of a nonocclusive thrombus. Factors that increase myocardial oxygen demand include the following:

- Arrhythmias

- Fever

- Hypertension

- Cocaine use

- Aortic stenosis

- Arteriovenous shunts

- Anemia

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Pheochromocytoma

- Congestive heart failure

Proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6, interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, C-reactive protein, and interleukin-17, are substantially elevated in the blood serum of patients with unstable angina. This finding suggests that the inflammatory process is activated in unstable angina.[16]

History and Physical

Patients often present with chest pain and shortness of breath. Chest pain typically presents as pressure-like but may also be described as tight, burning, or sharp. Patients frequently report discomfort rather than pain, which often radiates to the jaw or arms, affecting both the left and right sides. Constitutional symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, dizziness, and palpitations may accompany these complaints. Exertion can worsen the pain, while rest, nitroglycerin, and aspirin may provide relief. Any pain, pressure, tightness, or discomfort in the chest, neck, arms, shoulders, upper abdomen, or back, along with fatigue and shortness of breath, should be considered anginal equivalents.[17]

A key distinguishing feature of unstable angina is incomplete resolution of pain with typical relieving factors. Many patients have preexisting CAD, either previously diagnosed or with stable anginal symptoms. These patients often report increased frequency, duration, or severity of chest pain episodes; such changes suggest unstable angina rather than stable or other causes of chest pain. Recognizing these symptoms is critical, as unstable angina may indicate impending myocardial infarction or ST-elevation myocardial infarction, necessitating urgent evaluation due to higher morbidity and mortality risks compared to stable angina.[18]

Physical examination findings typically lack specificity for diagnosing unstable angina. However, thorough patient evaluation remains essential for immediate risk assessment, detection of potential hemodynamic effects, and identification of mechanical complications.[19] Findings suggestive of high-risk status include the following:

- Dyskinetic apex

- Elevated jugular venous pressure

- Presence of third or fourth heart sounds (S3 or S4)

- New apical systolic murmur

- Rales and crackles

- Hypotension

Current guidelines recommend using risk-stratification tools to assess prognosis and guide management.[20] Commonly employed risk scores include the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction risk score for non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction and the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events risk score.[21][22]

Evaluation

Patients require rapid evaluation with an electrocardiogram (ECG) to assess for ischemic signs or a possible ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), alongside close monitoring of vital signs and oxygenation. ECG findings in unstable angina may include hyperacute T-waves, flattened or inverted T-waves, and ST depression. ST elevations indicate STEMI, necessitating treatment with percutaneous coronary intervention or thrombolytics while awaiting catheterization laboratory availability.

Arrhythmias associated with ACS include junctional rhythms, sinus tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and left bundle branch block. However, most patients, especially with unstable angina, remain in sinus rhythm, unlike those with infarcted tissue. No specific ECG changes definitively diagnose unstable angina. Many patients exhibit normal or nonspecific ST-T changes. Therefore, a normal or nonspecific ECG does not exclude unstable angina.

Laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count to assess for anemia, a platelet count, and a basic metabolic profile to detect electrolyte abnormalities. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin testing is the standard for identifying myocardial infarction. Pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels may also be measured, as elevated values are associated with increased mortality risk. Coagulation studies are recommended when anticoagulation is planned or anticipated. A chest radiograph is often helpful in evaluating heart size and the mediastinum, aiding in the detection of other potentially serious causes of chest pain, such as aortic dissection.

The clinical history should be reviewed to rule out other emergent etiologies of chest pain or shortness of breath, including pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, esophageal rupture, pneumonia, and pneumothorax. Continuous cardiac monitoring is essential for detecting rhythm disturbances. Further evaluation may involve cardiac stress tests, such as treadmill stress testing, stress echocardiography, myocardial perfusion imaging, or cardiac computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Cardiac catheterization remains the gold standard.

These tests are typically ordered and performed by inpatient and primary care clinicians. However, with the expansion of observation medicine, emergency clinicians may also initiate them.[23][24] Urgent diagnostic testing is not recommended for patients with stable chest pain who are considered low risk. Still, those at intermediate or high risk should undergo cardiac imaging and further evaluation.

ACS risk assessment should include the following:

- Prior myocardial infarction or known history of coronary artery disease

- Transient ECG or hemodynamic changes during chest pain

- Chest, neck, or left arm consistent with angina

- ST depression or elevation of more than 1 mm

- Marked symmetrical T-wave inversion

These features raise the likelihood of ACS and should prompt expedited diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making. Recognizing these signs early is essential to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Treatment / Management

Management primarily aims to increase blood flow in the coronary arteries through diverse modalities. Treatment strategies should be tailored to the patient’s risk profile, symptom severity, and overall clinical presentation.

Antiplatelet Agents

Effective management of ACS requires prompt initiation of antiplatelet therapy to inhibit platelet activation and reduce clot progression. Aspirin combined with oral P2Y12 inhibitors remains the standard regimen to lower major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).

Aspirin

Aspirin is commonly administered for its antiplatelet effects, typically at a dose of 162 to 325 mg orally or 300 mg rectally if swallowing is not possible. Administration should occur within 30 minutes of presentation.

Ticagrelor

For patients with confirmed ACS, ticagrelor is administered as a 180-mg loading dose as early as possible, along with aspirin, followed by a maintenance dose of 90 mg orally twice daily for 12 months. After 12 months, the dose may be reduced to 60 mg twice daily, except in patients at high ischemic risk, who should continue 90 mg twice daily.

Prasugrel

Prasugrel is administered as a 60-mg oral loading dose before percutaneous coronary intervention in combination with aspirin, then maintained at 10 mg daily. For patients weighing less than 60 kg, the maintenance dose should be reduced to 5 mg daily. Prasugrel is contraindicated in patients with a history of transient ischemic attack or stroke due to poorer outcomes.

Clopidogrel

Clopidogrel is preferred for patients who have a high bleeding risk or are receiving concomitant anticoagulation therapy. The usual dose is 75 mg orally once daily, with an optional 300 mg loading dose administered before PCI in ACS.

Choice of antiplatelet agent

In all patients with ACS, an oral P2Y12 inhibitor should be used in conjunction with aspirin to reduce MACE. For patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS) undergoing PCI, either ticagrelor or prasugrel is recommended. Ticagrelor is preferred for patients with NSTE-ACS who are managed without planned invasive intervention to reduce MACE. Among patients with ACS undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, prasugrel may be favored over ticagrelor. When ticagrelor or prasugrel are unavailable, contraindicated, or not tolerated, clopidogrel serves as the recommended alternative.

Duration of therapy

Combination therapy with aspirin and an oral P2Y12 inhibitor is recommended for at least 12 months in patients without significant bleeding risk. Regular reassessment is necessary to balance bleeding and ischemic risks.

Special considerations

Patients at high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding should receive oral proton pump inhibitors. For patients requiring long-term anticoagulation for other conditions, aspirin may be discontinued 1 to 4 weeks after percutaneous coronary intervention, while continuing P2Y12 inhibitor therapy, preferably with clopidogrel. Ticagrelor monotherapy for 1 month or longer after PCI is advised for patients who have tolerated dual antiplatelet therapy with ticagrelor.

Nitroglycerin Administration

Nitroglycerin is available in multiple formulations—intravenous, sublingual, transdermal, and oral—and acts by dilating coronary arteries to enhance blood flow and lower blood pressure. This vasodilation reduces myocardial workload and oxygen demand, helping to relieve ischemic symptoms.

Supplemental Oxygen Therapy

Supplemental oxygen should be administered via nasal cannula to maintain adequate oxygen saturation. These 3 interventions—nitroglycerin, oxygen, and initial assessment—are critical for the rapid evaluation and management of unstable angina. Patients with persistent pain or delayed recovery require close monitoring, as they face a higher risk of progression to myocardial infarction.

Other Modalities

Other therapeutic modalities for unstable angina extend beyond the initial management strategies and include several pharmacologic and procedural options. Anticoagulation with either low- or high-molecular-weight heparin is commonly employed to prevent thrombus formation. β-blockers play a crucial role in reducing myocardial energy demand by lowering both heart rate and blood pressure.[25][26] Ranolazine has been studied in patients with unstable angina, showing a significant reduction in recurrent ischemia, making it a valuable adjunctive treatment.[27](A1)

Lipid-lowering therapy is a cornerstone in the management of ACS, with high-intensity statins recommended for all patients. Suppose low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) goals—typically equal to or less than 70 mg/dL—are not achieved with statins alone. In that case, additional agents such as ezetimibe or proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors should be introduced. Ezetimibe, when added to statin therapy, has demonstrated reductions in LDL-C and a decreased risk of major cardiovascular events, including nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, and unstable angina requiring rehospitalization or revascularization. PCSK9 inhibitors, such as alirocumab, evolocumab, and inclisiran, are reserved for patients who do not reach LDL-C targets despite receiving maximal statin and ezetimibe therapy.

Cardiac angiography plays a crucial role in the management of unstable angina, especially for patients with elevated risk scores or clinical indicators such as cardiogenic shock, depressed ejection fraction, angina refractory to medical therapy, new mitral regurgitation, or unstable arrhythmias. Early percutaneous coronary intervention in NSTEMI, typically within 6 hours, has been associated with lower mortality compared to delayed intervention. Additionally, patients with unstable angina undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention report significant improvements in quality of life by 3 months postprocedure compared to 1 month.[28](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for unstable angina is broad and includes both cardiac and noncardiac conditions. Careful assessment is essential to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure appropriate management. Clinical entities that can mimic unstable angina include the following:

- Aortic dissection

- Pericarditis

- Pneumothorax

- Pulmonary embolism

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Pneumonia

- Myocarditis

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Costochondritis

- Muscle spasm

- Panic attack

Accurate differentiation among these conditions is vital to guide urgent management and reduce the risk of adverse outcomes. Prompt identification ensures that life-threatening conditions such as aortic dissection or pulmonary embolism are not overlooked.

Prognosis

The critical complications of unstable angina include the following:

- Myocardial infarction

- Heart failure

- Ventricular arrhythmia

- Cardiac arrest

Study results indicate that patients with new-onset ST-segment elevation greater than 1 mm have a 12-month myocardial infarction or mortality rate of approximately 11%, compared to 7% among those with isolated T-wave inversion. Adverse prognostic factors include the following:

- Low ejection fraction

- Ongoing congestive heart failure

- New or worsening mitral regurgitation

- Hemodynamic instability

- Sustained ventricular tachycardia

- Recurrent episodes of angina despite maximal therapy

The atherogenic index of plasma, calculated as the logarithm (base 10) of the ratio of triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, serves as a novel biomarker for assessing the risk of coronary heart disease and atherosclerosis.[29] In patients with prediabetes, the atherogenic index of plasma demonstrates a significant correlation with the prognosis of unstable angina.[30] Additionally, exposure to specific air pollutants, particularly carbon monoxide and particulate matter with a diameter of 10 µm or less, has been associated with an increased risk of heart failure readmissions among patients with unstable angina.[31]

Complications

Although unstable angina is associated with lower mortality and relative incidence than NSTEMI, the risk of subsequent nonfatal myocardial infarction remains comparable.[32] Patients with unstable angina demonstrate a lower 1-year risk of death and MACE than those with NSTEMI. However, when compared to patients with stable angina undergoing coronary angiography without a prior history of coronary artery disease, unstable angina is associated with a nonsignificant difference in MACE risk but a higher risk of death.[33]

Consultations

A cardiologist should be consulted once a patient has been diagnosed with unstable angina. The cardiologist will stratify the patient’s risk and guide management decisions. Timely cardiology consultation ensures that patients receive comprehensive care aligned with current guidelines.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The primary goals of prevention are to help the patient resume all daily activities, preserve myocardial function, and reduce the risk of future cardiac events. Many cardiac centers now have specialized teams, such as cardiac rehabilitation programs, that provide intensive and effective counseling to support these goals. Smoking cessation is mandatory to prevent recurrent cardiac events and should be encouraged for all household members. Lipid-lowering therapy aims to achieve a target LDL-C level of 70 mg/dL or lower, a high-density lipoprotein level of at least 35 mg/dL, and triglycerides below 200 mg/dL. Patients should also adopt regular exercise routines and follow a low-fat diet.

Blood pressure targets are set below 140/90 mm Hg, along with reducing sodium and alcohol intake. Blood glucose levels can be managed through a combination of diet, exercise, and medication as needed. Patients are encouraged to lose weight to reach a body mass index of 25 kg/m². Additionally, individuals at risk for unstable angina should avoid intense physical exertion, especially in cold weather.

Pearls and Other Issues

Legally, unstable angina and other forms of ACS represent a significant proportion of cases brought against clinicians. This challenge has led to aggressive evaluation of chest pain in general, resulting in high rates of hospital admissions, extensive testing, and a notable number of false positives that often prompt unnecessary procedures. Over the years, several clinical decision rules have been developed to reduce inappropriate admissions and testing. However, the sensitivity and specificity of these guidelines vary widely. Despite ongoing litigation, clinicians tend to err on the side of caution, maintaining a relatively aggressive approach to the management and treatment of chest pain suggestive of ACS.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Unstable angina is a pervasive and serious condition frequently encountered in the emergency room. Management of this critical cardiac disorder is best handled by an interprofessional team, comprising primary healthcare professionals, nurses, pharmacists, cardiologists, and emergency clinicians who work collaboratively. Additionally, consultation with a cardiac surgeon is highly recommended. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have established evidence-based guidelines to support effective management of unstable angina.[34]

Once the patient is stabilized, prevention becomes paramount. Clinicians should strongly encourage smoking cessation, adoption of a heart-healthy diet, regular exercise, maintenance of a healthy body weight, and strict adherence to prescribed medications. Close follow-up is essential to ensure patients achieve their cardiac rehabilitation goals. Lipid-lowering therapy plays a crucial role in reducing the risk of recurrent unstable angina.

Pharmacists contribute by verifying dosing and monitoring for potential drug interactions, while clinicians and pharmacists jointly emphasize the importance of blood pressure control and diabetes management. Nurses are responsible for ongoing patient monitoring, assessing the effectiveness of treatment, and promptly alerting clinicians to any concerns. This coordinated interprofessional approach yields the best outcomes. Most hospitals now have specialized healthcare teams dedicated to managing unstable angina, ensuring familiarity with the latest guidelines and patient education on risk factor reduction and medication adherence.

Outcomes

Evidence shows that quality improvement programs are associated with the lowest morbidity rates and the best patient outcomes.[35] Implementing such programs leads to more consistent care and a reduction in complications for patients with ACS.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bergmark BA, Mathenge N, Merlini PA, Lawrence-Wright MB, Giugliano RP. Acute coronary syndromes. Lancet (London, England). 2022 Apr 2:399(10332):1347-1358. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02391-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35367005]

Chang AM, Fischman DL, Hollander JE. Evaluation of Chest Pain and Acute Coronary Syndromes. Cardiology clinics. 2018 Feb:36(1):1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2017.08.001. Epub 2017 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 29173670]

Tocci G, Figliuzzi I, Presta V, Miceli F, Citoni B, Coluccia R, Musumeci MB, Ferrucci A, Volpe M. Therapeutic Approach to Hypertension Urgencies and Emergencies During Acute Coronary Syndrome. High blood pressure & cardiovascular prevention : the official journal of the Italian Society of Hypertension. 2018 Sep:25(3):253-259. doi: 10.1007/s40292-018-0275-y. Epub 2018 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 30066227]

Smith R, Frazer K, Hyde A, O'Connor L, Davidson P. "Heart disease never entered my head": Women's understanding of coronary heart disease risk factors. Journal of clinical nursing. 2018 Nov:27(21-22):3953-3967. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14589. Epub 2018 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 29969829]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShah AP, Nathan S. Challenges in Implementation of Institutional Protocols for Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome. The American journal of cardiology. 2018 Jul 15:122(2):356-363. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.03.354. Epub 2018 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 29778236]

Libby P, Pasterkamp G, Crea F, Jang IK. Reassessing the Mechanisms of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Circulation research. 2019 Jan 4:124(1):150-160. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311098. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30605419]

Helwani MA, Amin A, Lavigne P, Rao S, Oesterreich S, Samaha E, Brown JC, Nagele P. Etiology of Acute Coronary Syndrome after Noncardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology. 2018 Jun:128(6):1084-1091. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002107. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29481375]

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (London, England). 2020 Oct 17:396(10258):1204-1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33069326]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, Boehme AK, Buxton AE, Carson AP, Commodore-Mensah Y, Elkind MSV, Evenson KR, Eze-Nliam C, Ferguson JF, Generoso G, Ho JE, Kalani R, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Levine DA, Lewis TT, Liu J, Loop MS, Ma J, Mussolino ME, Navaneethan SD, Perak AM, Poudel R, Rezk-Hanna M, Roth GA, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Thacker EL, VanWagner LB, Virani SS, Voecks JH, Wang NY, Yaffe K, Martin SS. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022 Feb 22:145(8):e153-e639. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052. Epub 2022 Jan 26 [PubMed PMID: 35078371]

Dagenais GR, Leong DP, Rangarajan S, Lanas F, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Gupta R, Diaz R, Avezum A, Oliveira GBF, Wielgosz A, Parambath SR, Mony P, Alhabib KF, Temizhan A, Ismail N, Chifamba J, Yeates K, Khatib R, Rahman O, Zatonska K, Kazmi K, Wei L, Zhu J, Rosengren A, Vijayakumar K, Kaur M, Mohan V, Yusufali A, Kelishadi R, Teo KK, Joseph P, Yusuf S. Variations in common diseases, hospital admissions, and deaths in middle-aged adults in 21 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet (London, England). 2020 Mar 7:395(10226):785-794. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32007-0. Epub 2019 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 31492501]

Chandrashekhar Y, Alexander T, Mullasari A, Kumbhani DJ, Alam S, Alexanderson E, Bachani D, Wilhelmus Badenhorst JC, Baliga R, Bax JJ, Bhatt DL, Bossone E, Botelho R, Chakraborthy RN, Chazal RA, Dhaliwal RS, Gamra H, Harikrishnan SP, Jeilan M, Kettles DI, Mehta S, Mohanan PP, Kurt Naber C, Naik N, Ntsekhe M, Otieno HA, Pais P, Piñeiro DJ, Prabhakaran D, Reddy KS, Redha M, Roy A, Sharma M, Shor R, Adriaan Snyders F, Weii Chieh Tan J, Valentine CM, Wilson BH, Yusuf S, Narula J. Resource and Infrastructure-Appropriate Management of ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Circulation. 2020 Jun 16:141(24):2004-2025. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041297. Epub 2020 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 32539609]

George J, Mathur R, Shah AD, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Denaxas S, Smeeth L, Timmis A, Hemingway H. Ethnicity and the first diagnosis of a wide range of cardiovascular diseases: Associations in a linked electronic health record cohort of 1 million patients. PloS one. 2017:12(6):e0178945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178945. Epub 2017 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 28598987]

Timmis A, Kazakiewicz D, Townsend N, Huculeci R, Aboyans V, Vardas P. Global epidemiology of acute coronary syndromes. Nature reviews. Cardiology. 2023 Nov:20(11):778-788. doi: 10.1038/s41569-023-00884-0. Epub 2023 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 37231077]

Heusch G. Myocardial Ischemia: Lack of Coronary Blood Flow or Myocardial Oxygen Supply/Demand Imbalance? Circulation research. 2016 Jul 8:119(2):194-6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308925. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27390331]

Manfredi R, Verdoia M, Compagnucci P, Barbarossa A, Stronati G, Casella M, Dello Russo A, Guerra F, Ciliberti G. Angina in 2022: Current Perspectives. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022 Nov 22:11(23):. doi: 10.3390/jcm11236891. Epub 2022 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 36498466]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZaremba YH, Smaliukh OV, Zaremba-Fedchyshyn OV, Zaremba OV, Kost AS, Lapovets LY, Tomkiv ZV, Holyk OM. Indicators of inflammation in the pathogenesis of unstable angina. Wiadomosci lekarskie (Warsaw, Poland : 1960). 2020:73(3):569-573 [PubMed PMID: 32285836]

Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, Amsterdam E, Bhatt DL, Birtcher KK, Blankstein R, Boyd J, Bullock-Palmer RP, Conejo T, Diercks DB, Gentile F, Greenwood JP, Hess EP, Hollenberg SM, Jaber WA, Jneid H, Joglar JA, Morrow DA, O'Connor RE, Ross MA, Shaw LJ. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30:144(22):e368-e454. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029. Epub 2021 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 34709879]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceByrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, Barbato E, Berry C, Chieffo A, Claeys MJ, Dan GA, Dweck MR, Galbraith M, Gilard M, Hinterbuchner L, Jankowska EA, Jüni P, Kimura T, Kunadian V, Leosdottir M, Lorusso R, Pedretti RFE, Rigopoulos AG, Rubini Gimenez M, Thiele H, Vranckx P, Wassmann S, Wenger NK, Ibanez B, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. European heart journal. 2023 Oct 12:44(38):3720-3826. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37622654]

Zeymer U, Bueno H, Granger CB, Hochman J, Huber K, Lettino M, Price S, Schiele F, Tubaro M, Vranckx P, Zahger D, Thiele H. Acute Cardiovascular Care Association position statement for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: A document of the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association of the European Society of Cardiology. European heart journal. Acute cardiovascular care. 2020 Mar:9(2):183-197. doi: 10.1177/2048872619894254. Epub 2020 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 32114774]

Rao SV, O'Donoghue ML, Ruel M, Rab T, Tamis-Holland JE, Alexander JH, Baber U, Baker H, Cohen MG, Cruz-Ruiz M, Davis LL, de Lemos JA, DeWald TA, Elgendy IY, Feldman DN, Goyal A, Isiadinso I, Menon V, Morrow DA, Mukherjee D, Platz E, Promes SB, Sandner S, Sandoval Y, Schunder R, Shah B, Stopyra JP, Talbot AW, Taub PR, Williams MS. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2025 Apr:151(13):e771-e862. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001309. Epub 2025 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 40014670]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAntman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, McCabe CH, Horacek T, Papuchis G, Mautner B, Corbalan R, Radley D, Braunwald E. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000 Aug 16:284(7):835-42 [PubMed PMID: 10938172]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFox KA, Fitzgerald G, Puymirat E, Huang W, Carruthers K, Simon T, Coste P, Monsegu J, Gabriel Steg P, Danchin N, Anderson F. Should patients with acute coronary disease be stratified for management according to their risk? Derivation, external validation and outcomes using the updated GRACE risk score. BMJ open. 2014 Feb 21:4(2):e004425. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004425. Epub 2014 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 24561498]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLu MT, Ferencik M, Roberts RS, Lee KL, Ivanov A, Adami E, Mark DB, Jaffer FA, Leipsic JA, Douglas PS, Hoffmann U. Noninvasive FFR Derived From Coronary CT Angiography: Management and Outcomes in the PROMISE Trial. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2017 Nov:10(11):1350-1358. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.11.024. Epub 2017 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 28412436]

Lippi G, Favaloro EJ. Myocardial Infarction, Unstable Angina, and White Thrombi: Time to Move Forward? Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 2019 Feb:45(1):115-116. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1657781. Epub 2018 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 29864773]

Taguchi I, Iimuro S, Iwata H, Takashima H, Abe M, Amiya E, Ogawa T, Ozaki Y, Sakuma I, Nakagawa Y, Hibi K, Hiro T, Fukumoto Y, Hokimoto S, Miyauchi K, Yamazaki T, Ito H, Otsuji Y, Kimura K, Takahashi J, Hirayama A, Yokoi H, Kitagawa K, Urabe T, Okada Y, Terayama Y, Toyoda K, Nagao T, Matsumoto M, Ohashi Y, Kaneko T, Fujita R, Ohtsu H, Ogawa H, Daida H, Shimokawa H, Saito Y, Kimura T, Inoue T, Matsuzaki M, Nagai R. High-Dose Versus Low-Dose Pitavastatin in Japanese Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease (REAL-CAD): A Randomized Superiority Trial. Circulation. 2018 May 8:137(19):1997-2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032615. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29735587]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCastini D, Centola M, Ferrante G, Cazzaniga S, Persampieri S, Lucreziotti S, Salerno-Uriarte D, Sponzilli C, Carugo S. Comparison of CRUSADE and ACUITY-HORIZONS Bleeding Risk Scores in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes. Heart, lung & circulation. 2019 Apr:28(4):567-574. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2018.02.012. Epub 2018 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 29526417]

Gutierrez JA, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Murphy SA, Belardinelli L, Farzaneh-Far R, Walker G, Morrow DA, Scirica BM. Effects of Ranolazine in Patients With Chronic Angina in Patients With and Without Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Acute Coronary Syndrome: Observations From the MERLIN-TIMI 36 Trial. Clinical cardiology. 2015 Aug:38(8):469-75. doi: 10.1002/clc.22425. Epub 2015 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 26059896]

Van Nguyen H, Khuong LQ, Nguyen AT, Nguyen ALT, Nguyen CT, Nguyen HTT, Tran TTH, Dao ATM, Gilmour S, Van Hoang M. Changes in, and predictors of, quality of life among patients with unstable angina after percutaneous coronary intervention. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2021 Apr:27(2):325-332. doi: 10.1111/jep.13416. Epub 2020 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 32542918]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNiroumand S, Khajedaluee M, Khadem-Rezaiyan M, Abrishami M, Juya M, Khodaee G, Dadgarmoghaddam M. Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP): A marker of cardiovascular disease. Medical journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2015:29():240 [PubMed PMID: 26793631]

Liu Y, Feng X, Yang J, Zhai G, Zhang B, Guo Q, Zhou Y. The relation between atherogenic index of plasma and cardiovascular outcomes in prediabetic individuals with unstable angina pectoris. BMC endocrine disorders. 2023 Aug 31:23(1):187. doi: 10.1186/s12902-023-01443-x. Epub 2023 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 37653411]

Zhang L, Liu Z, Zhou X, Zeng J, Wu M, Jiang M. Long-term impact of air pollution on heart failure readmission in unstable angina patients. Scientific reports. 2024 Sep 27:14(1):22132. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-73495-5. Epub 2024 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 39333793]

Puelacher C, Gugala M, Adamson PD, Shah A, Chapman AR, Anand A, Sabti Z, Boeddinghaus J, Nestelberger T, Twerenbold R, Wildi K, Badertscher P, Rubini Gimenez M, Shrestha S, Sazgary L, Mueller D, Schumacher L, Kozhuharov N, Flores D, du Fay de Lavallaz J, Miro O, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Morawiec B, Fahrni G, Osswald S, Reichlin T, Mills NL, Mueller C. Incidence and outcomes of unstable angina compared with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2019 Sep:105(18):1423-1431. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314305. Epub 2019 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 31018955]

Fladseth K, Wilsgaard T, Lindekleiv H, Kristensen A, Mannsverk J, Løchen ML, Njølstad I, Mathiesen EB, Trovik T, Rotevatn S, Forsdahl S, Schirmer H. Outcomes after coronary angiography for unstable angina compared to stable angina, myocardial infarction and an asymptomatic general population. International journal of cardiology. Heart & vasculature. 2022 Oct:42():101099. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2022.101099. Epub 2022 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 35937948]

Clark MG, Beavers C, Osborne J. Managing the acute coronary syndrome patient: Evidence based recommendations for anti-platelet therapy. Heart & lung : the journal of critical care. 2015 Mar-Apr:44(2):141-9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.11.005. Epub 2015 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 25592204]

Stamou SC, Camp SL, Stiegel RM, Reames MK, Skipper E, Watts LT, Nussbaum M, Robicsek F, Lobdell KW. Quality improvement program decreases mortality after cardiac surgery. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2008 Aug:136(2):494-499.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.08.081. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18692663]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence