Introduction

An anal fissure is a longitudinal tear of the anoderm distal to the dentate line and is a frequent cause of emergency department visits. Most fissures result from local trauma to the anoderm, commonly due to passage of hard or bulky stools, persistent irritation, anorectal surgery, or anoreceptive intercourse. Anal fissures occur in both adults and children, with increased frequency in individuals with chronic constipation. The lesions are classified as acute when symptoms last less than 6 weeks and chronic when they persist longer, often with hypertrophied anal papillae or sentinel tags.

Primary fissures occur predominantly at the posterior midline, with a smaller proportion at the anterior midline (see Image. Chronic Anal Fissure). Off-midline or multiple fissures are considered secondary and may indicate systemic conditions, such as Crohn disease, tuberculosis, malignancy, or trauma, requiring further evaluation. Diagnosis is primarily clinical, and management ranges from dietary modification and pharmacologic sphincter relaxation to surgical intervention for refractory disease. Treatment of secondary fissures focuses on addressing the underlying systemic or local condition to promote healing and prevent recurrence.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Anal fissures arise from various local and systemic factors. Common causes include constipation, chronic diarrhea, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), tuberculosis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), HIV, anal cancer, obstetric trauma, prior anorectal surgery, and anoreceptive intercourse. Most acute fissures result from the passage of hard stools, infectious proctitis, or direct trauma from anal penetration. Chronic fissures frequently stem from recurrences of acute episodes and develop when repeated mechanical trauma acts against elevated internal anal sphincter (IAS) tone, resulting in symptoms persisting beyond 6 weeks.

Physiologic studies consistently demonstrate (IAS) hypertonicity and hypertrophy in affected patients, leading to greater resting anal pressures and impaired anodermal perfusion. The resulting local ischemia contributes to poor healing and progression to chronicity. Atypical fissures, particularly those that are off-midline, multiple, or nonhealing, are often associated with normal or reduced IAS tone and may indicate systemic disease, including IBD, tuberculosis, HIV, malignancy, or consequences of prior anorectal surgery.[5] Approximately 40% of acute fissures progress to a chronic state.[6][7]

Epidemiology

Anal fissures can occur at any age but are most frequently diagnosed in younger and middle-aged individuals. Recurrent fissures in children should prompt evaluation for possible sexual abuse. Incidence is similar between sexes. In the U.S., an estimated 240,000 to 342,000 new cases are diagnosed annually, corresponding to an approximate 7.8% lifetime risk.[8]

Pathophysiology

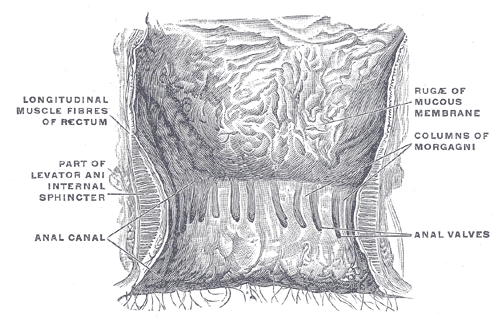

The anoderm, the epithelial lining of the anal canal, lies immediately distal to the dentate line (see Image. Anal Canal). This delicate tissue is highly susceptible to microtrauma and tearing from repetitive mechanical stress or elevated intraluminal pressure. Increased pressure impairs local perfusion, delaying healing. In some cases, tears may extend sufficiently to expose the internal or external sphincter muscle. These lesions, combined with sphincter spasms, produce severe pain during defecation and occasional rectal bleeding.

Anal fissures predominantly occur at the posterior midline, where blood flow is less than half that of other regions of the anal canal. Perfusion within the anal canal inversely correlates with sphincter pressure. Fissures occurring in lateral or other atypical locations often suggest underlying pathology, such as HIV, tuberculosis, or IBD, although the precise mechanisms remain unclear. Anterior fissures are rare and frequently associated with external sphincter injury or dysfunction.

Histopathology

Acute anal fissures exhibit sharply demarcated mucosal edges, occasional granulation tissue at the base, and minimal fibrosis, reflecting recent trauma. Chronic fissures show indurated margins, absence of granulation tissue, exposed horizontal fibers of the IAS, and fibrosis, often accompanied by sentinel skin tags or hypertrophied papillae.[9][10] Primary fissures typically demonstrate nonspecific ulceration, acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrates, granulation tissue, and reactive epithelial changes. Secondary fissures display histologic features related to underlying pathology, including epithelioid granulomas in Crohn disease, tuberculosis, or fungal infections, and plasma cell-rich infiltrates in syphilis or lymphogranuloma venereum, aiding differentiation from idiopathic lesions. (Source: Rishi and Cornish, Last Updated 2025)

Routine histopathologic evaluation is not required for most fissures. However, this diagnostic modality becomes important when ruling out malignancy or systemic pathology.

History and Physical

Acute anal fissures present with severe anal pain, typically exacerbated during defecation, and minor bleeding that appears as streaks rather than overt hemorrhage. Pain often persists for hours following bowel movements. Misdiagnosis as hemorrhoids is common, underscoring the importance of careful clinical examination. Chronic fissures cause prolonged, recurrent painful defecation with intermittent rectal bleeding, often in the setting of constipation or passage of hard stools. Granulomatous conditions, such as Crohn disease, may produce intermittent, recurrent anal pain associated with defecation over extended periods.

Examination should be performed with the patient in a position that minimizes discomfort. The prone jackknife position, with hips flexed, optimizes exposure and is preferred in procedure rooms. In outpatient or acute care settings, bending over an examination table or assuming the lateral decubitus position provides adequate visualization. Manipulation should be minimized, and digital rectal examination or instrumentation, including anoscopy, is generally avoided to reduce pain.

An acute anal fissure appears as a superficial, longitudinal laceration extending proximally from the anal verge. Bleeding may be absent or minimal, and both the fissure and the sphincter are typically exquisitely tender to palpation. Visualization is generally straightforward in lean individuals. In patients with obesity, gentle pressure over the anterior or posterior sphincter that reproduces pain can assist in localization. Chronic fissures present as larger, deeper defects, sometimes with exposed IAS fibers. Repeated injury and healing result in indurated margins and thickened distal tissue, forming a sentinel pile. Granulation tissue may be variably present, depending on the chronicity and reparative stage.

Evaluation

Examination under anesthesia is often indicated for chronic, recurrent anal fissures to facilitate accurate diagnosis and, in some cases, provide definitive treatment. The initial evaluation should determine whether the lesion is primary or secondary. Primary (typical) fissures occur at the posterior or anterior midline. In contrast, secondary fissures are located in atypical, nonmidline positions and warrant investigation for underlying conditions such as Crohn disease, infection, or malignancy. Importantly, individuals with systemic disorders such as Crohn disease may still develop fissures in typical locations. Chronic fissures frequently demonstrate the classic triad of sentinel tag, fissure, and hypertrophied anal papillae.[11]

Treatment / Management

Nonoperative Management

Initial management of anal fissures typically involves a 6-week trial of conservative measures. Recommended strategies include frequent sitz baths, analgesics, stool softeners, and a high-fiber diet to facilitate healing and reduce recurrence. Adequate hydration is also advised to minimize the risk of recurrent fissures. Maintenance fiber supplementation (eg, psyllium) after healing reduces recurrence. No single fiber type is superior.[12](A1)

Pharmacologic options are considered if conservative measures, including dietary modification and laxatives, fail. Topical treatments include lidocaine jelly (2%), topical nifedipine (0.2%-0.5%), topical nitroglycerin (0.2%-0.4%), or compounded combinations.[13][14] Lidocaine jelly is primarily for pain control and not a standalone fissure therapy. Topical nifedipine reduces IAS tone, increases local blood flow, and promotes healing. Nitroglycerin acts as a vasodilator to enhance perfusion and fissure recovery.(A1)

Topical nifedipine is generally preferred due to higher healing rates and fewer adverse effects. Nitroglycerin may induce headaches and hypotension. Patients are advised to apply nitroglycerin while seated and avoid rapid standing. Concurrent use with phosphodiesterase inhibitors, including sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil, is contraindicated.[15][16][17](A1)

Chronic anal fissures (CAFs) are often more challenging to manage due to their tendency to recur. When conservative measures fail, botulinum toxin injections provide an alternative by producing a reversible chemical sphincterotomy lasting up to 3 months. Healing rates with botulinum toxin are comparable to topical therapies but are lower than those achieved with surgical intervention. However, treatment with this neurotoxin offers the advantage of a reduced risk of fecal incontinence. Dosing and injection protocols vary widely, with some evidence suggesting lower doses may yield fewer adverse events without compromising efficacy. Botulinum toxin is a reasonable 1st-line alternative to topical agents or a 2nd-line after failure of topical therapy. Recurrent CAFs frequently require surgical management when nonoperative treatments prove insufficient.

Surgery

The gold standard surgical approach is lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS), which relieves fissures by reducing IAS hypertonia. Studies report that approximately 96% of patients achieve complete resolution within 3 weeks following LIS. The procedure may be performed via open or closed techniques under local or general anesthesia, though local anesthesia is associated with higher recurrence rates. In the open technique, an incision is made along the intersphincteric groove, the IAS is dissected from the mucosa, and the muscle is divided with scissors. The closed technique involves a small incision at the intersphincteric groove, insertion of a scalpel parallel to the sphincter, and rotation to divide the IAS. Healing rates are similar for both methods.

LIS is highly effective but carries potential complications. Fecal incontinence, including uncontrolled flatus, mild soiling, and gross stool leakage, is the most significant, affecting approximately 45% of patients immediately postoperatively, with a higher incidence in female patients (50% versus 30% in male patients). Incontinence is generally transient, with rates declining to less than 10% at 5 years post-LIS and gross stool incontinence occurring in under 1% of cases. The recurrence rate of CAFs after LIS is approximately 5%, compared with a 25% failure rate for conservative therapy.

Other acute complications include excessive bleeding, more common with the open technique and occasionally requiring suture ligation, and perianal abscess formation in about 1% of closed LIS cases, typically due to dead space created by mucosal separation. Rare long-term complications include keyhole deformity, predominantly following posterior fissure repair. In a cohort of over 600 patients, only 15 developed keyhole deformities, which were asymptomatic and did not result in incontinence, although surgical repair was performed.

For patients at higher risk of fecal incontinence, sphincter-preserving options such as anocutaneous advancement flap surgery (eg, dermal V-Y or house flaps) are recommended. These procedures have high healing rates (81%-100%), low rates of minor fecal incontinence (0%-6%), and, in comparative studies, lower risk of fecal incontinence than LIS (2% vs. 17%) while maintaining similar healing outcomes. When combined with botulinum toxin or LIS, flaps may reduce postoperative pain, accelerate healing, and further minimize fecal incontinence, with recurrence rates of 2% to 7%.

Management of Secondary Anal Fissures

General management of secondary anal fissures focuses on identifying and treating the underlying systemic, infectious, traumatic, or neoplastic causes. An interprofessional approach involving gastroenterologists, surgeons, infectious disease specialists, and other relevant clinicians is recommended. Initial management often includes conservative measures while addressing disease-specific therapy (eg, immunomodulators for Crohn disease or antibiotics for infections). Surgical intervention is reserved for refractory cases with controlled underlying disease to minimize complications, particularly preserving sphincter integrity to reduce incontinence risk. Monitoring and treating coexisting conditions is essential to improve healing and prevent recurrence.

Differential Diagnosis

Anal fissure is primarily a clinical diagnosis made on physical examination, which also aids in excluding other causes of rectal pain. Hemorrhoids are the most common alternative finding. However, pain is typically limited to external hemorrhoids, particularly when thrombosed. Perianal abscesses are another source of pain, often exacerbated during defecation, and may be accompanied by bleeding. These abscesses can progress to anal fistulas, which may present with bleeding or purulent discharge. Additional considerations include perianal ulcerations associated with STIs, IBD, and tuberculosis. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, a rare disorder of uncertain etiology, may also mimic fissure-related symptoms and is generally identified several centimeters proximal to the anal verge on sigmoidoscopy.

Prognosis

Acute anal fissures in otherwise low-risk patients generally respond to conservative therapy, with resolution occurring within several days to weeks. However, a subset of patients experience progression to CAF, necessitating pharmacologic intervention or surgical management. Surgical treatment achieves durable healing in more than 90% of cases, with complete resolution typically observed within 3 to 4 weeks postoperatively.[18]

Complications

Complications of anal fissures include bleeding, pain, secondary infection, and varying degrees of fecal incontinence. Fistula formation is the most serious complication, often necessitating surgical intervention.

Complications from anal fissure treatment may include transient fecal incontinence, most commonly flatus incontinence, following LIS. Other risks include bleeding, perianal abscess formation, and, rarely, keyhole deformity. Topical nitroglycerin may cause headaches or hypotension, while botulinum toxin injection carries a small risk of transient sphincter weakness.

Consultations

Primary anal fissures are most often managed in primary care, where conservative measures, such as increasing fiber intake, taking stool softeners, and using sitz baths, are recommended as 1st-line therapy. Referral to a colorectal surgeon is appropriate when fissures are refractory to medical therapy, become chronic, or are associated with complications requiring procedural intervention.

Secondary fissures, particularly lesions that are multiple, nonmidline, or slow to heal, warrant evaluation for an underlying condition. A gastroenterology consultation is indicated when gastrointestinal pathology, such as IBD, is suspected. Infectious disease specialists should be involved for conditions like STIs and tuberculosis. Rheumatology input may be appropriate when fissures are associated with systemic inflammatory or autoimmune disease, such as vasculitis or Behçet disease. Oncology referral is warranted when malignancy is suspected or confirmed. Coordinated management with dietitians, pain specialists, and nurse educators supports symptom control and helps minimize future episodes.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Anal fissure prevention starts with measures to maintain regular, soft stools and reduce anorectal trauma. High-fiber diets, including supplements such as psyllium, promote stool bulk and consistency, easing defecation and minimizing mucosal injury.[19] Adequate hydration and avoidance of straining further protect the anoderm.[20]

For individuals with fissures or risk factors for the development of these lesions, addressing bowel irregularities promptly through lifestyle and dietary changes reduces progression. In cases where fissures are related to underlying disease or recurrent trauma, targeted medical or surgical treatment mitigates complications and recurrence.[21][22]

Pearls and Other Issues

Accurate diagnosis of anal fissures relies on careful history-taking and physical examination, with attention to distinguishing these lesions from other anorectal conditions, such as hemorrhoids. Management begins with nonoperative strategies, particularly for acute fissures. Conservative treatment includes a high-fiber diet, stool softeners, and sitz baths to reduce sphincter spasm, soften stool, and promote mucosal healing.

Chronic primary anal fissures require escalation to topical pharmacologic therapy, typically nitrates or calcium channel blockers, which lower sphincter tone and enhance blood flow. Patients with refractory symptoms despite medical therapy may benefit from botulinum toxin injection or LIS, both of which are effective in promoting definitive healing. Long-term success depends on maintaining regular bowel habits and minimizing straining to reduce the risk of further mucosal injury.

In cases of secondary fissures, treatment emphasizes management of the underlying disorder, as sphincterotomy is generally contraindicated. Collaborative management with specialists, such as gastroenterologists, rheumatologists, oncologists, and infectious disease clinicians, may be required to ensure optimal outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team approach is optimal for the management of anal fissures, which are frequently encountered in primary care, urgent care, and emergency settings. Although generally benign, anal fissures can cause significant pain and adversely affect quality of life. Given their high prevalence, current guidelines recommend that most acute cases be managed in primary care through lifestyle modification, dietary adjustments, and laxatives, thereby reducing the need for surgical consultation.

Primary care providers and pharmacists play a central role in educating patients on preventing constipation, a key factor in reducing both the frequency and economic burden of anal fissures. Referral to a dietitian or nurse educator may assist patients in selecting foods that promote regular bowel habits. Nurses and pharmacists also provide essential support by counseling on analgesic use, sitz baths, and monitoring for complications or symptom progression that may warrant further intervention.

If conservative management proves unsuccessful, referral to a colorectal surgeon is recommended, as these specialists possess the expertise required to manage complex or refractory cases. In cases of secondary anal fissures, coordinated care with relevant specialists is critical for accurate diagnosis and comprehensive treatment. This collaborative, team-based strategy ensures that patients receive comprehensive care and facilitates a smooth transition to surgical management when indicated.

Outcomes

The overall prognosis is favorable for most patients who adhere to dietary and lifestyle modifications. For persistent or treatment-resistant fissures, surgical intervention may be necessary. Despite its high success rate, recurrence occurs in approximately 4% to 6% of patients, even after surgery.[23][24][25]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Anal Canal. This illustration shows a coronal view of the terminal rectum and anal canal. Prominent longitudinal muscle fibers of the rectum are visible. Other structures shown include the levator ani muscle, the internal sphincter, the anal canal, and the anal valves. The columns of Morgagni and the rugæ of the mucous membrane are also clearly depicted.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Chronic Anal Fissure. This clinical image shows a longitudinal tear in the posterior midline of the anal verge, characteristic of a chronic anal fissure. The fissure edges are hypertrophied, and a sentinel skin tag is visible distally. Surrounding mucosa exhibits erythema and mild edema. These features, along with the exposed internal anal sphincter muscle at the fissure base, indicate chronicity. The typical posterior midline location occurs due to localized ischemia from internal sphincter hypertonia, which impairs healing and promotes fissure persistence. This presentation is consistent with a chronic anal fissure, a common cause of severe anal pain and bleeding.

Jonathan Lund, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Salem AE, Mohamed EA, Elghadban HM, Abdelghani GM. Potential combination topical therapy of anal fissure: development, evaluation, and clinical study†. Drug delivery. 2018 Nov:25(1):1672-1682. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2018.1507059. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30430875]

Siddiqui J, Fowler GE, Zahid A, Brown K, Young CJ. Treatment of anal fissure: a survey of surgical practice in Australia and New Zealand. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2019 Feb:21(2):226-233. doi: 10.1111/codi.14466. Epub 2018 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 30411476]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCarter D, Dickman R. The Role of Botox in Colorectal Disorders. Current treatment options in gastroenterology. 2018 Dec:16(4):541-547. doi: 10.1007/s11938-018-0205-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30397849]

Salati SA. Anal Fissure - an extensive update. Polski przeglad chirurgiczny. 2021 Mar 12:93(4):46-56. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0014.7879. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34515649]

Lyle V, Young CJ. Anal fissures: An update on treatment options. Australian journal of general practice. 2024 Jan-Feb:53(1-2):33-35. doi: 10.31128/AJGP/05-23-6843. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38316476]

Choi YS, Kim DS, Lee DH, Lee JB, Lee EJ, Lee SD, Song KH, Jung HJ. Clinical Characteristics and Incidence of Perianal Diseases in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Annals of coloproctology. 2018 Jun:34(3):138-143. doi: 10.3393/ac.2017.06.08. Epub 2018 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 29991202]

Jamshidi R. Anorectal Complaints: Hemorrhoids, Fissures, Abscesses, Fistulae. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2018 Mar:31(2):117-120. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1609026. Epub 2018 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 29487494]

Ebinger SM, Hardt J, Warschkow R, Schmied BM, Herold A, Post S, Marti L. Operative and medical treatment of chronic anal fissures-a review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of gastroenterology. 2017 Jun:52(6):663-676. doi: 10.1007/s00535-017-1335-0. Epub 2017 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 28396998]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJonas M, Scholefield JH. Anal Fissure. Gastroenterology clinics of North America. 2001 Mar:30(1):167-81 [PubMed PMID: 11394029]

Brown AC, Sumfest JM, Rozwadowski JV. Histopathology of the internal anal sphincter in chronic anal fissure. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 1989 Aug:32(8):680-3 [PubMed PMID: 2752854]

Akinmoladun O, Oh W. Management of Hemorrhoids and Anal Fissures. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2024 Jun:104(3):473-490. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2023.11.001. Epub 2023 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 38677814]

Davids JS, Hawkins AT, Bhama AR, Feinberg AE, Grieco MJ, Lightner AL, Feingold DL, Paquette IM, Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Anal Fissures. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2023 Feb 1:66(2):190-199. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002664. Epub 2022 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 36321851]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAdanu KK, Iroko D, Amegan-Aho K, Adedia D, Ndudiri OV, Ali MA, Oyortey MA, Kpodonu J. Comparing the effectiveness and lubricity of a novel Shea lubricant to 2% lidocaine gel for digital rectal examination: a randomized non-inferiority trial. Scientific reports. 2023 Mar 22:13(1):4666. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-31555-2. Epub 2023 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 36949085]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNewman M, Collie M. Anal fissure: diagnosis, management, and referral in primary care. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2019 Aug:69(685):409-410. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X704957. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31345824]

Mahmoud NN, Halwani Y, Montbrun S, Shah PM, Hedrick TL, Rashid F, Schwartz DA, Dalal RL, Kamiński JP, Zaghiyan K, Fleshner PR, Weissler JM, Fischer JP. Current management of perianal Crohn's disease. Current problems in surgery. 2017 May:54(5):262-298. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2017.02.003. Epub 2017 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 28583256]

Stewart DB Sr, Gaertner W, Glasgow S, Migaly J, Feingold D, Steele SR. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anal Fissures. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2017 Jan:60(1):7-14 [PubMed PMID: 27926552]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVogel JD, Johnson EK, Morris AM, Paquette IM, Saclarides TJ, Feingold DL, Steele SR. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-in-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2016 Dec:59(12):1117-1133 [PubMed PMID: 27824697]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrady JT, Althans AR, Neupane R, Dosokey EMG, Jabir MA, Reynolds HL, Steele SR, Stein SL. Treatment for anal fissure: Is there a safe option? American journal of surgery. 2017 Oct:214(4):623-628. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.004. Epub 2017 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 28701263]

Hosseini SV. Lifestyle Modifications and Dietary Factors versus Surgery in Benign Anorectal Conditions; Hemorrhoids, Fissures, and Fistulas. Iranian journal of medical sciences. 2023 Jul:48(4):355-357. doi: 10.30476/ijms.2023.49356. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37456202]

Wang DC, Peng XF, Chen WX, Yu M. The Association of moisture intake and constipation among us adults: evidence from NHANES 2005-2010. BMC public health. 2025 Jan 31:25(1):399. doi: 10.1186/s12889-025-21346-x. Epub 2025 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 39891106]

Singh JP, Aleissa M, Drelichman ER, Mittal VK, Bhullar JS. Navigating the complexities of perianal Crohn's disease: Diagnostic strategies, treatment approaches, and future perspectives. World journal of gastroenterology. 2024 Nov 28:30(44):4745-4753. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i44.4745. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39610776]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRuymbeke H, Geldof J, De Looze D, Denis MA, De Schepper H, Dewint P, Gijsen I, Surmont M, Wyndaele J, Roelandt P. Secondary anal fissures: a pain in the a*. Acta gastro-enterologica Belgica. 2023 Jan-Mar:86(1):58-67. doi: 10.51821/86.1.11310. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36842176]

Sahebally SM, Meshkat B, Walsh SR, Beddy D. Botulinum toxin injection vs topical nitrates for chronic anal fissure: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2018 Jan:20(1):6-15. doi: 10.1111/codi.13969. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29166553]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSalih AM. Chronic anal fissures: Open lateral internal sphincterotomy result; a case series study. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2017 Mar:15():56-58. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2017.02.005. Epub 2017 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 28239456]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiang J, Church JM. Lateral internal sphincterotomy for surgically recurrent chronic anal fissure. American journal of surgery. 2015 Oct:210(4):715-9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.05.005. Epub 2015 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 26231724]