Introduction

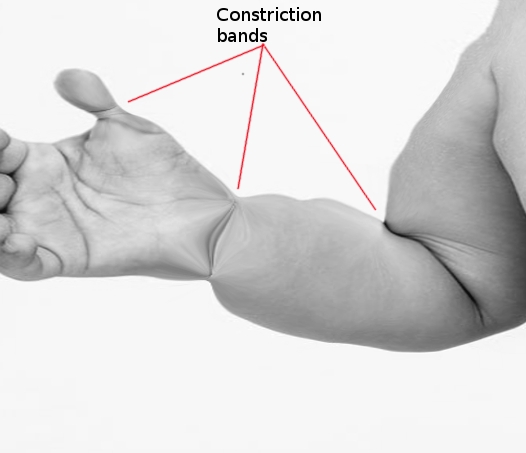

Amniotic band syndrome is a rare diagnosis with variable presentations. Although the underlying etiology of amniotic band syndrome remains unknown, the clinical consequences result from fetal parts becoming entangled in the amnion.[1] This entanglement leads to congenital anomalies by disruption, deformation, and malformation of organs that otherwise would have likely developed normally (see Image. Amniotic Band Syndrome). The severity ranges widely from mild isolated constriction rings to large abdominal wall defects.[2]

Amniotic band syndrome may be a misnomer and is better characterized as a sequence than a syndrome, as anomalies are related to an insult that can result from multiple etiologies. In contrast, a syndrome refers to patterns of congenital anomalies known to result from a single etiology (eg, Turner syndrome is due to XO chromosomal anomaly). Amniotic band syndrome has several synonyms: ADAM-sequence (amniotic deformity/adhesion/mutilation), amniotic disruption complex, congenital constricting bands, and Streeter dysplasia.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Several proposed amniotic band syndrome etiologies exist, including intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms. The most accepted mechanism is extrinsic, and it is theorized that early amnion rupture traps fetal parts between the amnion and chorion.[2] The cause of rupture is unknown, but it may be related to abnormal embryologic development or trauma.[3] Not all cases are associated with membrane disruption, and bands are often not visualized on prenatal ultrasound.[3]

Other proposals do not encompass the full spectrum of amniotic band syndrome but include etiologies such as local tissue developmental errors or vascular injury leading to band formation between the inflamed, hypoperfused tissue and the amnion.[4] Genetic etiologies have been explored, as rare familial and twin cases have been reported.[4] However, complete details on individual presentations are lacking, and when karyotyping was available, chromosomal studies were normal.[5][6]

Indeed, the underlying cause may be heterogeneous; however, amniotic band syndrome is not considered a hereditary or genetic condition. There is an association between invasive fetal procedures and amniotic band syndrome, referred to as post-procedural amniotic band disruption sequence. Single case reports describe amniotic band formation following routine amniocentesis and thoracoamniotic shunt placement; however, the phenomenon is more frequently documented after fetoscopic laser surgery in monozygotic twin pregnancies.[7][8][9] In case studies of twin pregnancies requiring treatment with fetoscopic laser surgery, there is an approximately 1% to 3% rate of post-procedural amniotic band disruption sequence. This risk appears to be increased when procedures are performed at earlier gestational ages, when the rates of chorion-amnion separation are higher, as the membrane layers may not be completely fused, wherein a lax amnion layer forms adhesive bands.[7]

Epidemiology

Given the broad range of clinical presentations related to amniotic band syndrome, the incidence is challenging to specify. Estimates range from 1 in 1200 to 15,000 live births.[10] Data from the European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies registry, which includes all births, reported a prevalence of 0.53 per 10,000 births from 1980 to 2019.[4] There are no apparent sex differences. The incidence is significantly higher among stillbirths (110 in 1000), which is related to the catastrophic effects amniotic bands can have on umbilical cord constriction.[4][8][11] In a case series of nearly 30 cases, the majority of defects resulting from amniotic band syndrome involved extremities (71%), followed by umbilical cord (25%) and complex abdominal wall defects (17.9%).[3]

Pathophysiology

The effects and severity of amniotic band syndrome likely depend on where the amniotic bands exist relative to the fetus. The adverse events likely result from constricting bands or rings that disrupt normal development, crowd or tether fetal parts, and disrupt normally developed structures.[12] This results in heterogeneous phenotypes with varying severity. Smaller peripheral bands are more likely to cause extremity defects, whereas broad bands spanning the uterine cavity may lead to major consequences, including complex abdominal wall defects.[3]

History and Physical

Amniotic band syndrome may be suspected after incidental prenatal ultrasound findings or anomalies identified postnatally. Amniotic band syndrome-related defects can be seen as early as the first trimester. This diagnosis should be considered in the setting of stillbirth, as well as unusual abdominal wall or cranial defects presenting along with limb constriction or amputation.

Prenatally, as with any congenital disability, the parental history should be reviewed for any personal or family history of congenital disabilities and teratogenic exposures. Due to the postulated mechanism of amniotic membrane disruption, the pregnant patient should also be asked about any clinical signs of membrane rupture and history of intrauterine procedures. Postnatally, in addition to the genetic and exposure histories, the neonate should undergo a complete physical examination with particular attention to the umbilical cord, digits and extremities, face, and head. Careful tracking of all defects and evaluation for gross evidence of fibrous strands is paramount.

Evaluation

Prenatally, patients should be referred to a maternal-fetal medicine consultation for a detailed anatomy ultrasound. This evaluation includes a thorough inspection of the fetal anatomy, with a specific assessment for amniotic bands. Moving the maternal patient during the ultrasound examination may unveil a fixed fetal position, which may suggest tethering or entrapment from amniotic bands. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging can be a useful complementary diagnostic tool in complex cases or for those considering intervention for amniotic band release, as ultrasound has a higher detection rate.[13]

Clinical presentation of amniotic band syndrome can be classified into 4 major categories:

- Constriction bands

- Limb defects

- Neural tube defects

- Craniofacial defects [3]

Constriction rings and limb or digital amputation are the most common findings. The amniotic bands may or may not be visible. Sonographically, amniotic bands appear as hyperechoic, thin, and linear structures. Color Doppler can be applied to demonstrate a lack of vascular flow within the suspected amniotic band. If constriction results in amputation in utero, a small remnant is produced, appropriately termed the "vestige sign."[14] Limb defects can include constriction rings, edema, absence of distal portions of 1 or more fingers and toes, clubbed feet and hands, pseudosyndactyly, contractures, and fractures. Upper extremities are affected more often.[5] If more than 1 limb is affected, the presentation is typically asymmetric. Color Doppler should be applied to all extremities of concern to evaluate perfusion proximal, at, and distal to the constriction. A grading system is used to classify the degree of limb involvement, guiding intervention.[15]

- Class 1: No signs of constriction

- Class 2a: No or mild lymphedema

- Class 2b: Severe lymphedema

- Class 3a: Abnormal distal Doppler studies

- Class 3b: No vascular flow to the extremity

- Class 4: Bowing or fracture of long bones

- Class 5: Intrauterine amputation

While less common, craniofacial abnormalities may be present, such as encephalocele, anencephaly, facial clefts, cleft lip/cleft palate, orbital involvement, and meningocele. These are often asymmetric and not along suture lines. Chest and abdominal wall defects have also been described, which include ectopia cordis, rib clefts, bowel extrusion, omphalocele, and bladder exstrophy. Spinal defects and scoliosis have been known to occur with amniotic band syndrome.[5]

Postnatally, amniotic band syndrome should be suspected in newborns with visible constrictions, amputations, and non-midline and unusually located craniofacial or body wall defects. There is frequent ocular involvement, such as microphthalmos, hypertelorism, ptosis, corneal opacities, eyelid colobomas, and lacrimal outflow obstruction.[16] Investigating the fresh fetal membranes and placenta can reveal amniotic bands, which should be examined in newborns with these findings.[8]

Treatment / Management

There are no established guidelines for managing amniotic band syndrome, and surveillance is individualized. All patients should receive counseling about identified anomalies and the possibility of additional undiagnosed abnormalities due to ultrasound's limitations in detecting all possible congenital disabilities and genetic syndromes. Pregnant individuals should continue receiving prenatal care with increased fetal surveillance, which often includes serial ultrasound evaluation of fetal growth and monitoring of affected areas.

The in-utero intervention of fetoscopic amniotic band lysis with laser or cold scissors can potentially slow the progression of constriction effects and restore normal blood flow to the downstream structures, which may salvage an at-risk limb or prevent stillbirth in the setting of a compromised umbilical cord.[15] There is a hypothesis that fetal limb recovery may be more likely after fetal intervention than after postnatal recovery due to the plasticity of tissue healing during fetal life.(B3)

However, the efficacy of this intervention is unknown, as there are no established criteria for candidate selection and a lack of clinical studies.[17] The primary risk associated with fetoscopic band release is preterm premature rupture of membranes, which affects 51% of cases in a recent systematic review. This results in a compounded risk of preterm delivery of over 70%. More than 75% of neonates in this study had preserved function of the affected limb; however, in 21.2% of cases, the limb required amputation postnatally to allow for prostheses.[18] Additional risks include fetal injury, intrauterine bleeding, and infection. (A1)

Postnatal management includes a thorough physical examination, multidisciplinary consultation with appropriate surgical teams, and, if needed, imaging studies to determine the extent of amniotic band syndrome. Relief of constriction rings postnatally, with excision of all scarred tissue, may help salvage some limb function. Vascular comprise diagnosed postnatally may require urgent surgical intervention.

Differential Diagnosis

Due to the heterogeneous consequences of amniotic band syndrome, there is a broad differential diagnosis for this condition, which includes the following:

- Body stalk anomaly: This is often accompanied by significant scoliosis, short umbilical cord, and adherence of the abdominal wall to the placenta.[19]

- Open defects: Major organ anomalies in the setting of amniotic band syndrome are often oblique and asymmetric and in the presence of additional limb abnormalities.

- Anencephaly: Proptotic orbits

- Cephalocele

- Acrania/acalvaria

- Cleft lip

- Gastroschisis

- Omphaloceles

- Amniotic sheets: Normal fetal anatomy; these sheets do not entrap fetal parts

- Chorioamniotic separation: Never entraps fetal parts

- Transverse limb deficiency: Distal limb defects due to vascular insults, no visible bands present

- Skeletal dysplasia: Characteristic skeletal findings are typically seen in conjunction with abnormal fetal growth measures

- Congenital varicella syndrome: Associated with maternal infection and limb defects present in a dermatomal distribution, which is often symmetric

- Caudal regression sequence: Symmetrically affects the lower extremities

- Teratogenic effects: Eg, thalidomide requires maternal exposure and often spares the head and face

- Trisomy 18: Associated with craniofacial abnormalities and limb defects; evaluate maternal age and history of prior aneuploidy screening

Prognosis

The prognosis of a newborn affected by amniotic band syndrome depends entirely on the extent of defects, from minor cosmetic defects to lethal involvement of vital organs. Patient counseling must be tailored to the fetal and neonatal clinical presentation resulting from amniotic band syndrome, which may require discussion of the termination of pregnancy and neonatal palliative care. A multidisciplinary approach involving fetal and neonatal teams is crucial for providing insight into potential interventions, functioning, and quality of life.

Isolated constriction alone is associated with good prognoses and normal life expectancies. There is a report of a resolved case of amniotic band syndrome affecting the fetal elbow, where extremity edema was resolved, and blood flow was preserved.[1] On the contrary, umbilical cord involvement is a significant risk factor for stillbirth. In a case series, 4 out of 5 stillbirths had amniotic band syndrome involving the umbilical cord.[3] Overall, there is an increased risk of premature preterm rupture of membranes and preterm birth, which is potentiated in the presence of abdominal wall defects. If present, the mean gestational age at delivery is 33.6 weeks, and there is an increased risk of low birth weight.[3][15]

Complications

As previously mentioned, the complications related to amniotic band syndrome depend on the extent of the fetal anomalies. Obstetric complications include stillbirth, preterm premature rupture of membranes, preterm birth, and low birth weight.

Consultations

A multidisciplinary team approach is essential for caring for patients with congenital anomalies. Consultation should be individualized based on the specific presentation of amniotic band syndrome. For example, family planning and palliative care should be considered in cases with life-limiting anomalies. Consultations may include the following:

- Obstetrician

- Maternal-fetal medicine

- Neonatology

- Pediatric radiology

- Pediatric surgery

- Social work

Deterrence and Patient Education

Healthcare professionals must tailor patient counseling for each case of amniotic band syndrome, as no 2 cases are the same. Patient education should focus on the anticipated functional and health effects of anomalies related to amniotic bands. Drawing and medical illustration can be useful educational tools to maximize patient understanding. Anticipatory guidance for surveillance and options for the postnatal care plan should be outlined.

In particular, severe, life-limiting anomalies should be clearly disclosed with a nonjudgmental discussion of available options for pregnancy continuation or discontinuation. Collaborating with social workers is critical to coordinating the financial and emotional support systems available at the patient's care institution. Given the current understanding that amniotic band syndrome is a sporadic and non-heritable condition, a medical genetics consultation may be of limited utility until more evidence is available.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing amniotic band syndrome requires a collaborative, patient-centered approach that involves physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, social workers, and other healthcare professionals. Physicians and advanced practitioners provide diagnostic accuracy through prenatal imaging and guide care plans, while nurses offer monitoring, education, and emotional support. The social worker is a critical member of the interprofessional approach to provide social, financial, and emotional support due to increased healthcare utilization and stress with a fetal diagnosis.

Suspicion of amniotic band syndrome warrants referral to maternal-fetal medicine to evaluate resultant anomalies comprehensively, counsel on anticipated neonatal outcomes, review pregnancy management options, design a surveillance and delivery plan, and coordinate pediatric subspecialty care. Because severe cases of amniotic band syndrome can lead to life-limiting anomalies, patients should be referred to institutions with the infrastructure to discuss and offer termination of pregnancy. Determining delivery location is a key aspect of care planning. Pregnancies complicated by amniotic band syndrome should be delivered at a hospital with access to radiology, neonatology, and pediatric surgical specialties if immediate surgical intervention is indicated.

Ethical care emphasizes informed decision-making, parental support, and fetal advocacy. Effective interprofessional communication, utilizing tools such as the Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation (SBAR) technique, and coordinated care among obstetric, pediatric, and surgical teams enhance outcomes, safety, and team performance by ensuring timely interventions and compassionate support throughout diagnosis, delivery, and postnatal care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Pedersen TK, Thomsen SG. Spontaneous resolution of amniotic bands. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001 Dec:18(6):673-4 [PubMed PMID: 11844214]

Quintero RA, Morales WJ, Phillips J, Kalter CS, Angel JL. In utero lysis of amniotic bands. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997 Nov:10(5):316-20 [PubMed PMID: 9444044]

Iqbal CW, Derderian SC, Cheng Y, Lee H, Hirose S. Amniotic band syndrome: a single-institutional experience. Fetal diagnosis and therapy. 2015:37(1):1-5. doi: 10.1159/000358301. Epub 2014 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 25531236]

Bergman JEH, Barišić I, Addor MC, Braz P, Cavero-Carbonell C, Draper ES, Echevarría-González-de-Garibay LJ, Gatt M, Haeusler M, Khoshnood B, Klungsøyr K, Kurinczuk JJ, Latos-Bielenska A, Luyt K, Martin D, Mullaney C, Nelen V, Neville AJ, O'Mahony MT, Perthus I, Pierini A, Randrianaivo H, Rankin J, Rissmann A, Rouget F, Sayers G, Schaub B, Stevens S, Tucker D, Verellen-Dumoulin C, Wiesel A, Gerkes EH, Perraud A, Loane MA, Wellesley D, de Walle HEK. Amniotic band syndrome and limb body wall complex in Europe 1980-2019. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2023 Apr:191(4):995-1006. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.63107. Epub 2022 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 36584346]

Lowry RB, Bedard T, Sibbald B. The prevalence of amnion rupture sequence, limb body wall defects and body wall defects in Alberta 1980-2012 with a review of risk factors and familial cases. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2017 Feb:173(2):299-308. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38016. Epub 2016 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 27739257]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGică N, Apostol LM, Gică C, Huluță I, Vayna AM, Panaitescu AM, Gana N. Amniotic Band Syndrome-Prenatal Diagnosis. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2023 Dec 23:14(1):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14010034. Epub 2023 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 38201342]

Knijnenburg PJC, Slaghekke F, Tollenaar LSA, Gijtenbeek M, Haak MC, Middeldorp JM, Klumper FJCM, van Klink JMM, Oepkes D, Lopriore E. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcome of postprocedural amniotic band disruption sequence after fetoscopic laser surgery in twin-twin transfusion syndrome: a large single-center case series. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2020 Oct:223(4):576.e1-576.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.016. Epub 2020 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 32335054]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStrauss A, Hasbargen U, Paek B, Bauerfeind I, Hepp H. Intra-uterine fetal demise caused by amniotic band syndrome after standard amniocentesis. Fetal diagnosis and therapy. 2000 Jan-Feb:15(1):4-7 [PubMed PMID: 10705208]

Han M, Afshar Y, Chon AH, Scibetta E, Rao R, Meyerson C, Chmait RH. Pseudoamniotic Band Syndrome Post Fetal Thoracoamniotic Shunting for Bilateral Hydrothorax. Fetal and pediatric pathology. 2017 Aug:36(4):311-318. doi: 10.1080/15513815.2017.1313915. Epub 2017 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 28453379]

Walter JH Jr, Goss LR, Lazzara AT. Amniotic band syndrome. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 1998 Jul-Aug:37(4):325-33 [PubMed PMID: 9710786]

Heinke D, Nestoridi E, Hernandez-Diaz S, Williams PL, Rich-Edwards JW, Lin AE, Van Bennekom CM, Mitchell AA, Nembhard WN, Fretts RC, Roberts DJ, Duke CW, Carmichael SL, Yazdy MM, National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Risk of Stillbirth for Fetuses With Specific Birth Defects. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020 Jan:135(1):133-140. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003614. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31809437]

Higginbottom MC, Jones KL, Hall BD, Smith DW. The amniotic band disruption complex: timing of amniotic rupture and variable spectra of consequent defects. The Journal of pediatrics. 1979 Oct:95(4):544-9 [PubMed PMID: 480028]

Neuman J, Calvo-Garcia MA, Kline-Fath BM, Bitters C, Merrow AC, Guimaraes CV, Lim FY. Prenatal imaging of amniotic band sequence: utility and role of fetal MRI as an adjunct to prenatal US. Pediatric radiology. 2012 May:42(5):544-51. doi: 10.1007/s00247-011-2296-8. Epub 2011 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 22134536]

Barzilay E, Harel Y, Haas J, Berkenstadt M, Katorza E, Achiron R, Gilboa Y. Prenatal diagnosis of amniotic band syndrome - risk factors and ultrasonic signs. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2015 Feb:28(3):281-3. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.915935. Epub 2014 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 24735486]

Hüsler MR, Wilson RD, Horii SC, Bebbington MW, Adzick NS, Johnson MP. When is fetoscopic release of amniotic bands indicated? Review of outcome of cases treated in utero and selection criteria for fetal surgery. Prenatal diagnosis. 2009 May:29(5):457-63. doi: 10.1002/pd.2222. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19235736]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMadan S, Chaudhuri Z. Amniotic Band Syndrome: A Review of 2 Cases. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2018 Jul/Aug:34(4):e110-e113. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001107. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29634607]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJavadian P, Shamshirsaz AA, Haeri S, Ruano R, Ramin SM, Cass D, Olutoye OO, Belfort MA. Perinatal outcome after fetoscopic release of amniotic bands: a single-center experience and review of the literature. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013 Oct:42(4):449-55. doi: 10.1002/uog.12510. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23671033]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFerrer-Marquez F, Peiro JL, Tonni G, Ruano R. Fetoscopic Release of Amniotic Bands Based on the Evidence-A Systematic Review. Prenatal diagnosis. 2024 Sep:44(10):1231-1241. doi: 10.1002/pd.6636. Epub 2024 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 39080813]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGică N, Apostol LM, Huluță I, Panaitescu AM, Vayna AM, Peltecu G, Gana N. Body Stalk Anomaly. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2024 Feb 29:14(5):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14050518. Epub 2024 Feb 29 [PubMed PMID: 38472990]