Introduction

Amebiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica, transmitted via the fecal-oral route through the ingestion of cysts.[1] Sir William Osler first diagnosed the disease in 1890.[2] The infection can be asymptomatic or present with diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, or extraintestinal complications, most commonly liver abscess.

Men aged 18 to 50 are most commonly affected. Endemic regions include India, Africa, Mexico, and Central and South America.[1] Symptoms typically develop within 2 to 4 weeks, with fever and right upper quadrant pain; 10% to 35% also report gastrointestinal symptoms.[3][4] Diagnosis relies on clinical presentation, epidemiological context, imaging, and serologic testing. Optimal treatment includes metronidazole followed by a luminal agent such as paromomycin. Therapeutic aspiration or surgical intervention is rarely required.[5][6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

E histolytica is a parasitic protozoan responsible for approximately 40 million infections and up to 100,000 deaths annually.[7] In contrast, Entamoeba despar and Entamoeba moshkovskii, which also infect humans via the fecal-oral route, are nonpathogenic; individuals may remain asymptomatic carriers.[7] Among the Entamoeba species infecting humans, only E histolytica causes clinical amebiasis. Humans and non-human primates are the only known natural hosts.[8]

Epidemiology

Amebic liver abscesses are uncommon in children and occur 10 times more frequently in men than in women, most commonly affecting individuals between the ages of 18 and 50. The reason for this disparity remains unclear but may relate to hormonal influences and alcohol consumption. Most cases in the United States occur in immigrants from endemic regions and individuals living along the US-Mexico border. E histolytica is widely distributed globally, with the highest infection rates in India, Africa, Mexico, and Central and South America.

Risk is most significant in areas with poor sanitation and unsafe municipal water supplies.[7] Transmission typically occurs through ingestion of contaminated food or water. Other routes include oral and anal sexual contact, particularly among men who have sexual intercourse with men.[9] Approximately 2% to 5% of patients with intestinal amebiasis progress to liver abscess formation.[2]

Pathophysiology

Clifford Dobell first described the life cycle of E histolytica in 1928. The organism has 2 stages: the infective cystic stage and the invasive trophozoite stage.[2] Infection begins with the ingestion of quadrinucleate cysts through contaminated food or water. Excystation occurs in the small intestine, releasing motile trophozoites. In most cases, these remain in the intestinal mucosa and form new cysts. Sometimes, trophozoites adhere to and lyse the colonic epithelium, leading to tissue invasion.

This invasion triggers a neutrophilic response, causing further cellular damage at the invasion site. Trophozoites can then disseminate via the portal circulation to extraintestinal sites, most commonly the liver, where they can cause inflammation and necrosis, leading to abscess formation.[10][11] Hepatocyte death, through apoptosis or necrosis, contributes to abscess development.[12]

Toxicokinetics

E histolytica adheres to colonic epithelial cells via a galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine-specific lectin. The organism exhibits cytolytic activity and can induce apoptosis in mammalian cells. Upon reaching the liver, trophozoites form abscesses characterized by well-circumscribed areas of liquified cellular debris and necrotic hepatocytes. These lesions are surrounded by a rim of connective tissue containing inflammatory cells and amebic trophozoites. The relatively low number of organisms within large abscesses suggests that E histolytica can mediate hepatocyte destruction without direct cell contact.

History and Physical

Patients can present with an amebic liver abscess months to years after travel to an endemic region, making a detailed travel history and awareness of epidemiologic risk factors imperative. In the United States, typical cases occur in Hispanic immigrant men aged 20 to 40. About 80% of patients develop symptoms within 2 to 4 weeks of exposure, including fever, dull right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, and cough. Subacute presentations may involve weight loss with less frequent fever or abdominal pain. Gastrointestinal symptoms occur in 10% to 35% of cases, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, constipation, or distention.

Risk factors include:

- Recent travel to tropical regions

- Malnutrition

- Immunosuppression

- Alcohol abuse

On physical examination, hepatomegaly with point tenderness in the right upper quadrant or right intercostal spaces is typical of a liver abscess. A minority of patients may present with severe distress or shock, including septic or anaphylactic shock in rare cases, such as hydatid cyst rupture.

Evaluation

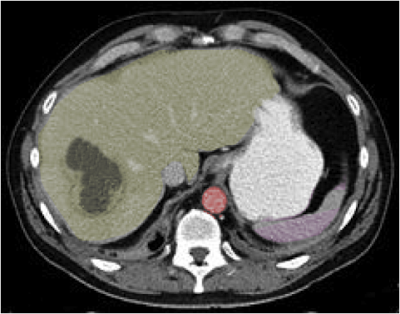

On laboratory evaluation, patients with amebic liver abscesses typically exhibit leukocytosis, elevated serum transaminases, and increased alkaline phosphatase levels. Most abscesses are located in the right hepatic lobe and measure 2 to 6 cm in diameter. Radiographic findings are sensitive but not specific for amebic liver abscess. Common imaging modalities include ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with typical findings as follows:

- Ultrasound:

- Round or oval, internally homogeneous, hypoechoic masses

- CT:

- Low-density lesion with a peripheral enhancing rim (see Image. Hepatic Abscess, Computed Tomography [CT])

- May show septations or fluid-solid levels

- MRI:

- Low signal intensity on T1-weighted image

- High signal intensity on the T2-weighted image

A history of travel to an endemic area, combined with typical clinical features and characteristic imaging findings, should raise suspicion for amebic liver abscess. Serologic testing via indirect hemagglutination has over 95% sensitivity, though sensitivity is 70% to 80% in acute disease and exceeds 90% in the convalescent phase. False-negative results may occur during the first week of illness. Stool microscopy is limited, with a sensitivity of only 10% to 40%.[13] Aspiration is generally not indicated, but if performed, the abscess yields a thick, odorless, chocolate-brown fluid classically described as "anchovy paste".[12][14]

Treatment / Management

Treatment involves a nitroimidazole, preferably metronidazole 500 to 750 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 to 10 days. Alternatively, tinidazole 2 g can be administered once daily for 3 days. Because intestinal colonization persists in 40% to 60% of cases, nitroimidazole therapy must always be followed by a luminal agent, such as paromomycin 500 mg 3 times daily for 7 days or iodoquinol 650 mg 3 times daily for 20 days [11]. Metronidazole and paromomycin should not be administered simultaneously, as paromomycin-induced diarrhea may complicate assessment of treatment response. Clinical improvement typically occurs within 72 to 96 hours.[15]

Approximately 15% of patients do not respond to medical treatment and may require abscess aspiration or surgical intervention. Therapeutic percutaneous aspiration can be performed via needle aspiration or catheter drainage. These procedures are indicated in patients who fail to improve within 5 to 7 days of antibiotic therapy, have a high risk of rupture (eg, abscess >5 cm or left lobe involvement), or present with bacterial coinfection of the amebic liver abscess.[16]

Among the 2 techniques, percutaneous catheter drainage has shown superior outcomes, with higher success rates and faster symptom resolution than needle aspiration.[17] Surgical intervention is reserved for the following indications: (A1)

- Multiple loculated abscesses or those in inaccessible locations for percutaneous drainage

- Failure of percutaneous drainage to eradicate the abscess(es)

- Bacterial superinfection of the abscess(es)

- Rupture of the abscess into the peritoneum or pericardium poses a significant risk for amebic peritonitis, cardiac complications, and death; these are considered a surgical emergency.[18] (B3)

When feasible, laparoscopic drainage is preferred over open surgery as it offers reduced postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery while maintaining effective abscess resolution.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of amebic liver abscess requires careful distinction from other causes of hepatic lesions. A broad differential is essential to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure appropriate management. The differential includes:

- Pyogenic liver abscesses

- These often arise from cholangitis, intra-abdominal infection, or hematogenous spread. Common pathogens include Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and intestinal gram-negative organisms, such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp.

- Cholangitis, a frequent source of hepatic infection

- Echinococcal liver abscesses

- Melioidosis, caused by disseminated Burkholderia pseudomallei bacterial infection

- Hydatid cysts due to Echinococcus granulosus

- These may rupture or become secondarily infected.

- Fungal abscesses, especially Candida spp

- These typically occur in immunocompromised individuals.

- Hepatic trauma

- Secondary spread from intra-abdominal infections, such as diverticulitis, appendicitis, or bowel perforation

- Hepatocellular carcinoma or other malignancies involving the liver

Prognosis

For uncomplicated amebic liver abscesses, the prognosis is excellent with appropriate medical therapy. Most patients respond well to treatment without requiring invasive intervention. However, when an abscess ruptures into the peritoneum, the mortality rate after surgical management ranges from 20% to 50%. In such cases, percutaneous catheter drainage is the preferred approach.[19] Cardiac involvement, though rare, carries a high mortality rate, often due to cardiac tamponade.[20] Prompt recognition and emergency intervention are critical in these cases.

Complications

An amebic liver abscess may rupture into the lungs, pleural cavity, pericardium, or abdomen. Abdominal rupture can lead to peritonitis, increasing the risk of shock and death. Cardiac involvement, usually due to rupture into the pericardium, may result in acute pericarditis, pericardial abscess, tamponade, constrictive pericarditis, myocarditis, or congestive heart failure.[20] Rare complications include thrombosis of the inferior vena cava or hepatic vein and hematogenous spread to distant organs, such as the brain.

Consultations

Management of amebic liver abscess often requires a multidisciplinary approach. Consultation with appropriate specialists ensures comprehensive care and optimal outcomes. Key consultations may include:

- Gastroenterology

- General surgery

- Interventional radiology

- Infectious disease specialist

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventive measures focus on reducing fecal contamination of food and water and emphasizing safe sexual practices, particularly among men who have sexual intercourse with men. The development of an effective vaccine could significantly improve health outcomes in developing countries, particularly among children. Once considered a fatal disease, amebic liver abscess is now largely curable with appropriate treatment.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about amebic liver abscess include the following:

- Amebic liver abscess is caused by E histolytica and is transmitted via the fecal-oral route.

- This disease is most common in men aged 20 to 50 and individuals who have traveled to or lived in endemic regions such as India, Africa, Mexico, and Central or South America.

- Symptoms include fever, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, cough, weight loss, diarrhea, nausea, and other gastrointestinal complaints.

- Diagnosis is made using serologic testing with a sensitivity of over 95%. Stool microscopy has a low sensitivity, ranging from 10% to 40%. Imaging such as ultrasound, CT, or MRI shows a hypoechoic or low-density lesion. Aspiration yields a thick, odorless, brown fluid known as “anchovy paste.”

- Treatment involves metronidazole 500 to 750 mg 3 times daily for 7 to 10 days, followed by a luminal agent such as paromomycin. Metronidazole and paromomycin should not be administered simultaneously.

- Aspiration or surgery is needed if the abscess is larger than 5 cm, in the left lobe, does not respond to antibiotics within 5 to 7 days, has a bacterial superinfection, or ruptures into the peritoneum or pericardium.

- Complications include peritonitis, cardiac tamponade, pleural effusion, hepatic vein or inferior vena cava thrombosis, and (rare) spread to the brain or lungs.

- Prognosis is excellent with prompt treatment, but worsens with delayed care or rupture.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of amebic liver abscess depends on its complexity and requires a coordinated interprofessional team to reduce morbidity and mortality.[21] Serum antigen detection and stool microscopy are often initial diagnostic tests, highlighting the role of laboratory technologists in accurate diagnosis. For complex cases, interventional radiology may be needed for percutaneous drainage, while multilocular or inaccessible abscesses may require a general surgeon's laparoscopic or open surgical intervention.

Because many of the drugs used to treat amebic liver abscesses have adverse effects, a pharmacist may collaborate with clinicians to optimize medication choices and be attentive to possible adverse drug reactions. For example, emetine is used as a second-line drug in the treatment of amebiasis, including liver abscesses. Still, it is essential to monitor the patient as the drug has significant neurologic adverse effects and may cause cardiac arrhythmias.

The nurse may need to monitor the patient in an outpatient clinic to ensure that symptoms are being treated effectively and the condition resolves. The nurse plays a vital role in public education regarding sanitary measures, personal hygiene, and food preparation and handling. Patients considering travel to areas where amebiasis is endemic may wish to schedule an infectious disease consultation to discuss precautions, such as boiling drinking water, washing food regularly, and modifying sexual practices to avoid fecal-oral contamination.

When an interprofessional team approach is undertaken, the prognosis for most patients with an amebic liver abscess is excellent.[22] When complications such as rupture into the lung, pleural cavity, pericardium, or abdomen occur, patients with amebic liver abscesses need prompt consultation with one or more specialists in infectious diseases, cardiology, or pulmonology for treatment. Current evidence suggests that the drainage of complex abscesses can improve outcomes compared to medical management.[23] Effective communication and care coordination across disciplines are essential to ensure timely diagnosis, prevent complications, and improve patient safety and outcomes. A team-based, patient-centered approach enhances clinical performance and reduces morbidity in patients with amebic liver abscess.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Nasrallah J, Akhoundi M, Haouchine D, Marteau A, Mantelet S, Wind P, Benamouzig R, Bouchaud O, Dhote R, Izri A. Updates on the worldwide burden of amoebiasis: A case series and literature review. Journal of infection and public health. 2022 Oct:15(10):1134-1141. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.08.013. Epub 2022 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 36155852]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceArellano-Aguilar G, Marín-Santillán E, Castilla-Barajas JA, Bribiesca-Juárez MC, Domínguez-Carrillo LG. A brief history of amoebic liver abscess with an illustrative case. Revista de gastroenterologia de Mexico. 2017 Oct-Dec:82(4):344-348. doi: 10.1016/j.rgmx.2016.05.007. Epub 2017 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 28438363]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSalles JM, Salles MJ, Moraes LA, Silva MC. Invasive amebiasis: an update on diagnosis and management. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2007 Oct:5(5):893-901 [PubMed PMID: 17914922]

Hoffner RJ, Kilaghbian T, Esekogwu VI, Henderson SO. Common presentations of amebic liver abscess. Annals of emergency medicine. 1999 Sep:34(3):351-5 [PubMed PMID: 10459092]

Lardière-Deguelte S, Ragot E, Amroun K, Piardi T, Dokmak S, Bruno O, Appere F, Sibert A, Hoeffel C, Sommacale D, Kianmanesh R. Hepatic abscess: Diagnosis and management. Journal of visceral surgery. 2015 Sep:152(4):231-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2015.01.013. Epub 2015 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 25770745]

Wijewantha HS. Liver Disease in Sri Lanka. Euroasian journal of hepato-gastroenterology. 2017 Jan-Jun:7(1):78-81. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1217. Epub 2017 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 29201778]

Kannathasan S, Murugananthan A, Kumanan T, de Silva NR, Rajeshkannan N, Haque R, Iddawela D. Epidemiology and factors associated with amoebic liver abscess in northern Sri Lanka. BMC public health. 2018 Jan 10:18(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5036-2. Epub 2018 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 29316900]

Stanley SL Jr. Amoebiasis. Lancet (London, England). 2003 Mar 22:361(9362):1025-34 [PubMed PMID: 12660071]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKannathasan S, Murugananthan A, Kumanan T, Iddawala D, de Silva NR, Rajeshkannan N, Haque R. Amoebic liver abscess in northern Sri Lanka: first report of immunological and molecular confirmation of aetiology. Parasites & vectors. 2017 Jan 7:10(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1950-2. Epub 2017 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 28061872]

Albenmousa A, Sanai FM, Singhal A, Babatin MA, AlZanbagi AA, Al-Otaibi MM, Khan AH, Bzeizi KI. Liver abscess presentation and management in Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom. Annals of Saudi medicine. 2011 Sep-Oct:31(5):528-32. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.84635. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21911993]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWuerz T, Kane JB, Boggild AK, Krajden S, Keystone JS, Fuksa M, Kain KC, Warren R, Kempston J, Anderson J. A review of amoebic liver abscess for clinicians in a nonendemic setting. Canadian journal of gastroenterology = Journal canadien de gastroenterologie. 2012 Oct:26(10):729-33 [PubMed PMID: 23061067]

Khim G, Em S, Mo S, Townell N. Liver abscess: diagnostic and management issues found in the low resource setting. British medical bulletin. 2019 Dec 11:132(1):45-52. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldz032. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31836890]

Wong WK, Foo PC, Olivos-Garcia A, Noordin R, Mohamed Z, Othman N, Few LL, Lim BH. Parallel ELISAs using crude soluble antigen and excretory-secretory antigen for improved serodiagnosis of amoebic liver abscess. Acta tropica. 2017 Aug:172():208-212. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.05.017. Epub 2017 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 28506795]

Chang CY, Radhakrishnan AP. Amoebic liver abscess. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2022:55():e0665. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0665-2021. Epub 2022 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 35239920]

Priyadarshi RN, Kumar R, Anand U. Amebic liver abscess: Clinico-radiological findings and interventional management. World journal of radiology. 2022 Aug 28:14(8):272-285. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v14.i8.272. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36160830]

Waghmare M, Shah H, Tiwari C, Khedkar K, Gandhi S. Management of Liver Abscess in Children: Our Experience. Euroasian journal of hepato-gastroenterology. 2017 Jan-Jun:7(1):23-26. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1206. Epub 2017 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 29201767]

Cai YL, Xiong XZ, Lu J, Cheng Y, Yang C, Lin YX, Zhang J, Cheng NS. Percutaneous needle aspiration versus catheter drainage in the management of liver abscess: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB : the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2015 Mar:17(3):195-201. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12332. Epub 2014 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 25209740]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePriyadarshi RN, Prakash V, Anand U, Kumar P, Jha AK, Kumar R. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous catheter drainage of various types of ruptured amebic liver abscess: a report of 117 cases from a highly endemic zone of India. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2019 Mar:44(3):877-885. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1810-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30361869]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKumar R, Anand U, Priyadarshi RN, Mohan S, Parasar K. Management of amoebic peritonitis due to ruptured amoebic liver abscess: It's time for a paradigm shift. JGH open : an open access journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2019 Jun:3(3):268-269. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12144. Epub 2019 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 31276048]

Nunes MC, Guimarães Júnior MH, Diamantino AC, Gelape CL, Ferrari TC. Cardiac manifestations of parasitic diseases. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2017 May:103(9):651-658. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309870. Epub 2017 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 28285268]

Kouamé N, N'goan-Domoua AM, Akaffou E, Konan AN. [Multidisciplinary management of amebic liver abscesses at the University Hospital of Yopougon, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire]. The Pan African medical journal. 2010:7():25 [PubMed PMID: 21918712]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKale S, Nanavati AJ, Borle N, Nagral S. Outcomes of a conservative approach to management in amoebic liver abscess. Journal of postgraduate medicine. 2017 Jan-Mar:63(1):16-20. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.191004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27652983]

Lübbert C, Wiegand J, Karlas T. Therapy of Liver Abscesses. Viszeralmedizin. 2014 Oct:30(5):334-41. doi: 10.1159/000366579. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26287275]