Introduction

Acute acalculous cholecystitis is a form of cholecystitis in the absence of gallstones caused by abnormal gallbladder emptying, cholestasis, and hypoperfusion in the setting of acute illness. The most commonly encountered condition of cholecystitis is caused by a mechanical blockage of the gallbladder outlet at the cystic duct, typically due to the presence of a gallstone. Duncan first described the condition of acute acalculous cholecystitis in 1844.

Although acalculous cholecystitis usually presents in the acute setting, chronic acalculous cholecystitis typically presents more insidiously. The condition is more common in critically ill patients in the intensive care unit. Acute acalculous cholecystitis can be a life-threatening disorder that has a high risk of perforation and necrosis compared to the more typical calculous disease.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Gallbladder dysfunction in the absence of gallstones has a multifactorial etiology. Long periods of fasting, total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and drastic weight loss can all increase the incidence of acute acalculous cholecystitis. Often, other more serious conditions are present. Patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) recovering from major surgeries or other life-threatening ailments, eg, a stroke, heart attack, sepsis, severe burns, and extensive trauma, are all at a higher risk of developing acute acalculous cholecystitis.

Gallbladder stasis can develop due to a lack of gallbladder stimulation by cholecystokinin (CCK), leading to the concentration of bile salts and increased pressure within the gallbladder. The elevated pressure leads to hypoperfusion and ischemia of the gallbladder wall that eventually causes pressure necrosis and perforation if prompt intervention is not initiated. This static condition also increases the seeding and growth of common enteric pathogens, eg, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Bacteroides, Proteus, Pseudomonas, and Enterococcus faecalis.[4]

Individuals with chronic acalculous cholecystitis may have decreased gallbladder emptying or hypokinetic biliary dyskinesia due to a variety of factors, including hormone imbalance, vasculitis, and decreased nerve innervation secondary to conditions such as diabetes. Often, the exact etiology of chronic acalculous cholecystitis is unknown.[5][6]

Epidemiology

Acute acalculous cholecystitis accounts for 10% of all cases of acute cholecystitis and 5% to 10% of all cases of cholecystitis. Males are more commonly afflicted than females, with a mean age of 50.[7] Despite the close relationship between acute acalculous cholecystitis and critical illness, studies have shown that individuals with underlying vascular disease can develop acute acalculous cholecystitis in the outpatient setting.[8] Rates are increased in HIV and other immunosuppressed patients. These individuals are more susceptible to opportunistic infections, including microsporidia, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Cryptosporidium, and Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), which can seed and flourish in bile within the gallbladder. Carriers of Giardia lamblia, Helicobacter pylori, and Salmonella typhi are also associated with increased risks of developing cholecystitis.[9][10]

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of acute acalculous cholecystitis is complex, with the interplay of several mechanisms. Prolonged fasting and long-term TPN seen in critically ill patients can lead to biliary stasis within the gallbladder due to the lack of CCK stimulation.[11] Stasis of the gallbladder results in the build-up of intraluminal pressure against the gallbladder wall and distention. The gallbladder wall develops an inflammatory reaction, characterized by significant thickening and inflammation of the gallbladder wall. Prolonged biliary stasis can lead to bacterial colonization, contributing to the inflammatory response. If the pressure is not relieved promptly, the gallbladder wall loses its primary source of blood supply from the cystic artery, which is prone to ischemia.[12] Progressive gallbladder wall ischemia will result in necrotic or gangrenous changes. A necrotic gallbladder wall will eventually perforate and stimulate a systemic inflammatory response, followed by sepsis and shock.

Chronic acalculous cholecystitis usually presents more insidiously. Symptoms are more prolonged and may be less severe. Symptoms may also be more intermittent and vague, although patients can present with signs of acute biliary colic.[9][13] Although acute acalculous cholecystitis is often associated with critical illness, several mechanisms have been reported in patients without critical illness, including gallbladder vasculitis, biliary tree obstruction, and bile acid sequestration.[11]

Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis Types

Acute acalculous cholecystitis can be divided into the following 4 types:

- Uncomplicated cholecystitis (gallbladder inflammation without necrosis or perforation)

- Acute suppurative cholecystitis (an inflamed gallbladder with associated purulence)

- Gangrenous cholecystitis (gallbladder wall necrosis)

- Perforated cholecystitis (gallbladder wall rupture) [14]

Histopathology

Acute acalculous cholecystitis may present with varying degrees of inflammation, and the findings are similar to those of calculus cholecystitis but without gallstones. The gallbladder wall will be thickened to variable degrees, and there may be adhesions to the serosal surface. Smooth muscle hypertrophy, especially in chronic conditions, is often present. At times, sludge or viscous bile can be seen. These findings can be precursors to gallstone formation due to increased bile salts or stasis.

Various species of bacteria can be present in 11% to 30% of cases. Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses, also known as adenomyomatosis, are often present in specimens of chronic cholecystitis. These are herniations of intraluminal sinuses from increased intraluminal pressure, possibly associated with ducts of Luschka, which are small aberrant bile ducts found along the gallbladder fossa. The gallbladder mucosa will exhibit varying degrees of inflammation, from mild to moderate ulcerations with gangrenous changes. Extreme situations may show total gangrenous changes of the gallbladder with perforation.[15]

Toxicokinetics

Mild cases of acute acalculous cholecystitis are usually only treated for symptoms of biliary colic, but more severe cases can lead to sepsis and shock. The pressurized, static intraluminal bile can be susceptible to bacterial seeding. Antibiotics are usually ineffective because they do not treat the increased intraluminal pressure and subsequent ischemia. Eventual gallbladder perforation will lead to bile peritonitis and contribute to the body's systemic inflammatory response and sepsis.

History and Physical

Acute acalculous cholecystitis may present similarly to calculous cholecystitis. Patients typically present with right upper quadrant abdominal pain that worsens with fatty foods, physical exam findings of right upper quadrant tenderness, and a positive Murphy's sign (ie, inspiratory arrest from pain during palpation of the right upper quadrant). Fever, chills, body aches, nausea, vomiting, and food intolerance may also be present. These patients are often already admitted to the ICU for another severe illness or are recovering from extensive surgery. Critically ill patients unable to participate in the physical exam may have fevers of unknown origin or grimacing during abdominal palpation, which should prompt additional testing.

Evaluation

Laboratory Studies

Preliminary laboratory studies typically include a complete blood count, a basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and lipase levels. Findings of leukocytosis and elevated liver enzymes, including alkaline phosphatase and direct bilirubin, are common.

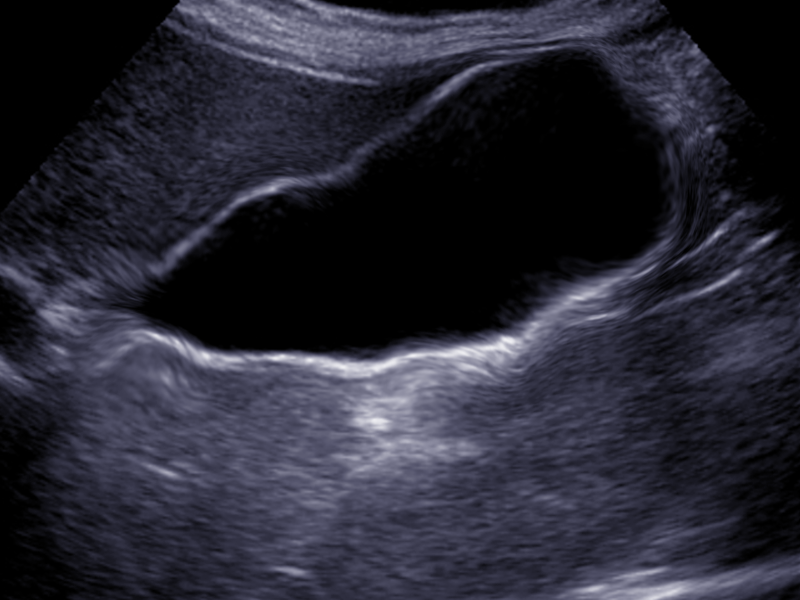

Ultrasound Imaging

Ultrasound is usually the initial image obtained, as this can be completed at the bedside in a timely fashion and is cost-effective. Gallbladder wall thickening >3 mm, gallbladder wall edema, and pericholecystic fluid are indicative of cholecystitis (see Image. Acalculous Cholecystitis).

Additional Diagnostic Studies

The test of choice for diagnosing acute acalculous cholecystitis in the setting of a normal ultrasound is a hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan, which may be done in conjunction with administration of CCK.[16] A HIDA scan evaluates the function or ejection fraction of the gallbladder. After the radionuclide is administered, CCK is given to stimulate gallbladder emptying.

A calculated ejection fraction of ≤35% may be indicative of hypokinetic functioning of the gallbladder.[17] HIDA scan may also demonstrate no filling of the gallbladder with radiotracer material, indicative of cystic duct obstruction and acute cholecystitis.[6][18] Computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen with intravenous contrast may also reveal gallbladder wall thickening, edema, and pericholecystic fluid in the absence of gallstones and sludge.

Treatment / Management

Stabalization and Antibiotic Therapy

Patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis should receive appropriate fluid resuscitation and broad-spectrum antibiotics that provide coverage for gram-negative rods and anaerobes, ideally after blood cultures have been obtained. Antibiotics alone are usually ineffective as they inadequately penetrate the pressurized gallbladder.[5][19][20] Individuals requiring ICU-level care should be properly stabilized before undergoing operative intervention.(A1)

Percutaneous Cholecystostomy Tube and Stent Placement

In those patients who are too unstable to undergo surgery, clinicians should consider interventional radiology consultation for percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement.[21] Percutaneous drainage is often the definitive treatment because acute acalculous cholecystitis has a lower recurrence rate when compared to acute calculous cholecystitis. The cholecystostomy tube can be removed after 3 weeks.[22] After percutaneous drainage and recovery, outpatient tube studies by interventional radiology can confirm patency of the cystic duct before removal. Alternatively, the patient can undergo cholecystectomy between 4 and 8 weeks after tube placement.[23]

Another treatment option is cystic duct stent placement via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to decompress the gallbladder and prevent cystic duct obstruction.[24] However, this approach is not as widely available as percutaneous cholecystostomy, and outcomes have not been studied as extensively.

Surgical Management

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the preferred definitive approach. However, an open cholecystectomy can also be performed if a contraindication to a minimally invasive approach is identified. Acute acalculous cholecystitis must be addressed fairly urgently because rapid progression and deterioration may result if left untreated. Chronic acalculous cholecystitis is treated similarly to chronic calculous cholecystitis with laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

A robotic approach should be considered depending on the surgeon's experience. Studies suggest that a robotic approach may be associated with a shorter hospital stay and a lower conversion rate to an open approach when compared with a laparoscopic approach.[25](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses that should also be considered when evaluating acalculous cholecystitis include:

- Biliary colic

- Calculous cholecystitis

- Choledocholithiasis

- Cholangitis

- Pancreatitis

- Hepatitis

- Gastritis

- Peptic Ulcer Disease

- Appenditis

- Mesenteric ischemia

Prognosis

Acute acalculous cholecystitis is a serious illness that has high morbidity and mortality, which is in part due to the critically ill patient population. The reported mortality rate of acute acalculous cholecystitis varies from 30% to 75%.[26][27] Patients who recover also have a long recovery.

Complications

The following complications are associated with acalculous cholecystitis:

- Perforation of the gallbladder

- Gangrene of the gallbladder

- Sepsis

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Most patients can be discharged home the same day or the day after cholecystectomy. Depending on whether the gallbladder was gangrenous or perforated, antibiotics may be warranted postoperatively.

Over-the-counter analgesics usually provide adequate pain control, but a short course of narcotics can be considered. Complaints of shoulder pain following laparoscopic surgery, which is caused by referred pain from the diaphragm and retained CO2 gas, are common. However, this pain typically resolves over the next few days as the patient increases mobility and the CO2 is slowly reabsorbed. Postoperative follow-up with the surgeon typically occurs 2 to 4 weeks after the procedure.

Before being discharged home, the patient should be advised about the potential for fatty food intolerance, which can cause abdominal bloating or diarrhea. This intolerance is usually temporary but may persist for a prolonged period due to the decreased speed of fat emulsification resulting from the loss of stored bile in the gallbladder. Most patients will experience an increase in bile production by the liver and will see an improvement in symptoms over time.

Consultations

Clinicians frequently involved with the management of acalculous cholecystitis include:

- General surgeon

- Gastroenterologist

- Radiologist

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence of acalculous cholecystitis focuses on identifying and mitigating risk factors, particularly in critically ill patients. Educating healthcare team members and caregivers about the importance of early mobilization, minimizing prolonged fasting, and closely monitoring patients receiving total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or experiencing rapid weight loss is essential. While direct patient education may be limited due to the typical ICU setting in which this condition arises, informing patients and families about potential complications of critical illness, including gallbladder issues, can aid in shared decision-making. Early recognition and proactive management remain key in preventing severe outcomes like gallbladder perforation or necrosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of acute acalculous cholecystitis requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach due to the high acuity and complexity of the condition. Physicians, including intensivists and surgeons, must rapidly assess and stabilize critically ill patients, initiate timely diagnostic imaging, and determine the need for surgical intervention or percutaneous drainage. Advanced practitioners support this by performing thorough assessments, monitoring clinical progress, and facilitating communication among team members. Nurses play a critical role at the bedside, maintaining vigilant observation for subtle signs of deterioration, managing fluid balance, monitoring respiratory status, and ensuring adherence to preventive measures such as deep vein thrombosis and ulcer prophylaxis. Close collaboration with radiologists and gastroenterologists ensures timely procedural interventions, such as percutaneous cholecystostomy or ERCP-guided gallbladder decompression, when surgery is not immediately feasible.

Pharmacists contribute by tailoring antimicrobial therapy to cover likely pathogens, adjusting dosages for organ dysfunction, and preventing medication-related complications. Dietitians assess nutritional needs, particularly for NPO patients who may require IV nutrition. Physical therapists provide bedside rehabilitation to prevent deconditioning and promote recovery in frail patients. Effective communication among all team members ensures consistent updates, accurate documentation, and shared decision-making centered around patient goals and safety. The complex nature of acalculous cholecystitis, combined with its high morbidity and mortality rate, underscores the need for seamless interprofessional collaboration, clear role delineation, and a unified focus on improving patient-centered outcomes and maximizing functional recovery despite the guarded prognosis.[18][28]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rezkallah KN, Barakat K, Farrah A, Rao S, Sharma M, Chalise S, Zdunek T. Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis due to primary acute Epstein-Barr virus infection treated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy; a case report. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2018 Nov:35():189-191. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.10.010. Epub 2018 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 30364603]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKwatra NS, Nurko S, Stamoulis C, Falone AE, Grant FD, Treves ST. Chronic Acalculous Cholecystitis in Children With Biliary Symptoms: Usefulness of Hepatocholescintigraphy. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2019 Jan:68(1):68-73. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002151. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30256266]

Iqbal S, Khajinoori M, Mooney B. A case report of acalculous cholecystitis due to Salmonella paratyphi B. Radiology case reports. 2018 Dec:13(6):1116-1118. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2018.07.013. Epub 2018 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 30233740]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang AJ, Wang TE, Lin CC, Lin SC, Shih SC. Clinical predictors of severe gallbladder complications in acute acalculous cholecystitis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2003 Dec:9(12):2821-3 [PubMed PMID: 14669342]

Walsh K, Goutos I, Dheansa B. Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis in Burns: A Review. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2018 Aug 17:39(5):724-728. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irx055. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29931066]

Thampy R, Khan A, Zaki IH, Wei W, Korivi BR, Staerkel G, Bathala TK. Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis in Hospitalized Patients With Hematologic Malignancies and Prognostic Importance of Gallbladder Ultrasound Findings. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2019 Jan:38(1):51-61. doi: 10.1002/jum.14660. Epub 2018 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 29708270]

Ganpathi IS, Diddapur RK, Eugene H, Karim M. Acute acalculous cholecystitis: challenging the myths. HPB : the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2007:9(2):131-4. doi: 10.1080/13651820701315307. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18333128]

Savoca PE, Longo WE, Zucker KA, McMillen MM, Modlin IM. The increasing prevalence of acalculous cholecystitis in outpatients. Results of a 7-year study. Annals of surgery. 1990 Apr:211(4):433-7 [PubMed PMID: 2322038]

Yi DY, Chang EJ, Kim JY, Lee EH, Yang HR. Age, Predisposing Diseases, and Ultrasonographic Findings in Determining Clinical Outcome of Acute Acalculous Inflammatory Gallbladder Diseases in Children. Journal of Korean medical science. 2016 Oct:31(10):1617-23. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.10.1617. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27550491]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIsmaili-Jaha V, Toro H, Spahiu L, Azemi M, Hoxha-Kamberi T, Avdiu M, Spahiu-Konjusha S, Jaha L. Gallbladder ascariasis in Kosovo - focus on ultrasound and conservative therapy: a case series. Journal of medical case reports. 2018 Jan 13:12(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s13256-017-1536-4. Epub 2018 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 29329599]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMarkaki I, Konsoula A, Markaki L, Spernovasilis N, Papadakis M. Acute acalculous cholecystitis due to infectious causes. World journal of clinical cases. 2021 Aug 16:9(23):6674-6685. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6674. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34447814]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThomaidou E, Karlafti E, Didagelos M, Megari K, Argiriadou E, Akinosoglou K, Paramythiotis D, Savopoulos C. Acalculous Cholecystitis in COVID-19 Patients: A Narrative Review. Viruses. 2024 Mar 15:16(3):. doi: 10.3390/v16030455. Epub 2024 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 38543820]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLe Bail B. [Pathology of gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. Case 1. Alcalculous gangrenous cholecystitis]. Annales de pathologie. 2014 Aug:34(4):271-8. doi: 10.1016/j.annpat.2014.06.006. Epub 2014 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 25132438]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFu Y, Pang L, Dai W, Wu S, Kong J. Advances in the Study of Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis: A Comprehensive Review. Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2022:40(4):468-478. doi: 10.1159/000520025. Epub 2021 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 34657038]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCroteau DI. Functional gallbladder disorder: an increasingly common diagnosis. American family physician. 2014 May 15:89(10):779-84 [PubMed PMID: 24866212]

Gallaher JR, Charles A. Acute Cholecystitis: A Review. JAMA. 2022 Mar 8:327(10):965-975. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.2350. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35258527]

Vassiliou MC, Laycock WS. Biliary dyskinesia. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2008 Dec:88(6):1253-72, viii-ix. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2008.07.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18992594]

Noh SY, Gwon DI, Ko GY, Yoon HK, Sung KB. Role of percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute acalculous cholecystitis: clinical outcomes of 271 patients. European radiology. 2018 Apr:28(4):1449-1455. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5112-5. Epub 2017 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 29116391]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSoria Aledo V, Galindo Iñíguez L, Flores Funes D, Carrasco Prats M, Aguayo Albasini JL. Is cholecystectomy the treatment of choice for acute acalculous cholecystitis? A systematic review of the literature. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas. 2017 Oct:109(10):708-718. doi: 10.17235/reed.2017.4902/2017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28776380]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLiu W, Chen W, He X, Qu Q, Hong T, Li B. Successful treatment using corticosteroid combined antibiotic for acute acalculous cholecystitis patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Medicine. 2017 Jul:96(27):e7478. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007478. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28682919]

Nve E, Badia JM, Amillo-Zaragüeta M, Juvany M, Mourelo-Fariña M, Jorba R. Early Management of Severe Biliary Infection in the Era of the Tokyo Guidelines. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023 Jul 16:12(14):. doi: 10.3390/jcm12144711. Epub 2023 Jul 16 [PubMed PMID: 37510826]

Huffman JL, Schenker S. Acute acalculous cholecystitis: a review. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2010 Jan:8(1):15-22. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.034. Epub 2009 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 19747982]

Woodward SG, Rios-Diaz AJ, Zheng R, McPartland C, Tholey R, Tatarian T, Palazzo F. Finding the Most Favorable Timing for Cholecystectomy after Percutaneous Cholecystostomy Tube Placement: An Analysis of Institutional and National Data. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2021 Jan:232(1):55-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.10.010. Epub 2020 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 33098966]

Storm AC, Vargas EJ, Chin JY, Chandrasekhara V, Abu Dayyeh BK, Levy MJ, Martin JA, Topazian MD, Andrews JC, Schiller HJ, Kamath PS, Petersen BT. Transpapillary gallbladder stent placement for long-term therapy of acute cholecystitis. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2021 Oct:94(4):742-748.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.03.025. Epub 2021 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 33798540]

Lunardi N, Abou-Zamzam A, Florecki KL, Chidambaram S, Shih IF, Kent AJ, Joseph B, Byrne JP, Sakran JV. Robotic Technology in Emergency General Surgery Cases in the Era of Minimally Invasive Surgery. JAMA surgery. 2024 May 1:159(5):493-499. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2024.0016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38446451]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBarie PS, Fischer E. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 1995 Feb:180(2):232-44 [PubMed PMID: 7850064]

Cornwell EE 3rd, Rodriguez A, Mirvis SE, Shorr RM. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in critically injured patients. Preoperative diagnostic imaging. Annals of surgery. 1989 Jul:210(1):52-5 [PubMed PMID: 2662924]

Treinen C, Lomelin D, Krause C, Goede M, Oleynikov D. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in the critically ill: risk factors and surgical strategies. Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2015 May:400(4):421-7. doi: 10.1007/s00423-014-1267-6. Epub 2014 Dec 25 [PubMed PMID: 25539703]