Familial Atypical Multiple Mole and Melanoma Syndrome

Familial Atypical Multiple Mole and Melanoma Syndrome

Introduction

Familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome is a rare hereditary disorder characterized by the presence of numerous clinically atypical nevi, often more than 50, and a significantly increased lifetime risk of melanoma. First described in 1820 by William Norris as a “fungoid disease,” FAMMM, also known as dysplastic nevus syndrome, presents substantial challenges in diagnosis and management due to its phenotypic variability and unpredictable clinical course.[1]

FAMMM syndrome results from inherited mutations in tumor suppressor genes associated with melanoma susceptibility, most notably CDKN2A, CDK4, and ARF.[2][3] This genetic predisposition confers a markedly elevated risk of melanoma development compared to the general population. About 5-10% of cutaneous melanomas occur due to hereditary predisposition; of these patients, approximately 20% to 40% have CDKN2A mutations.[1]

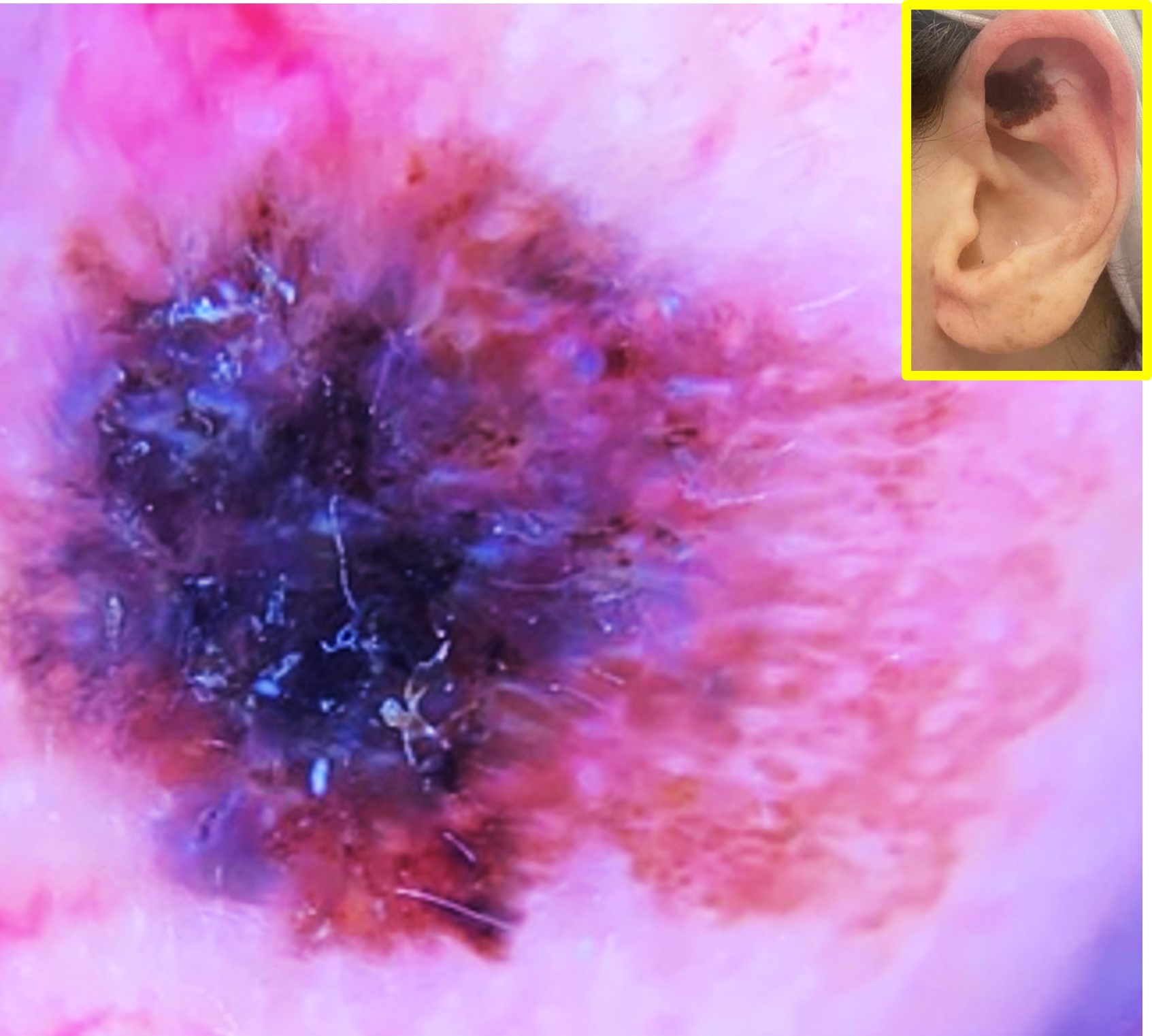

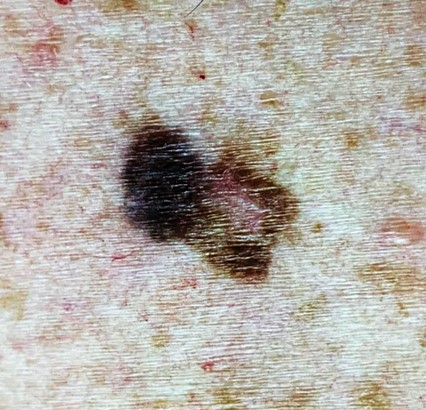

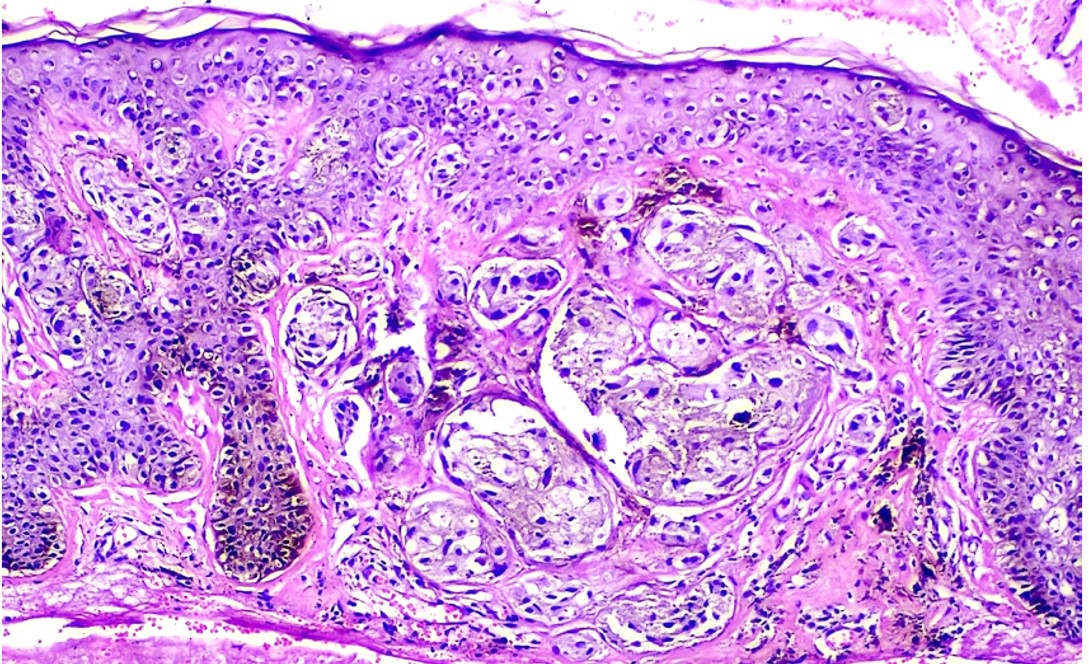

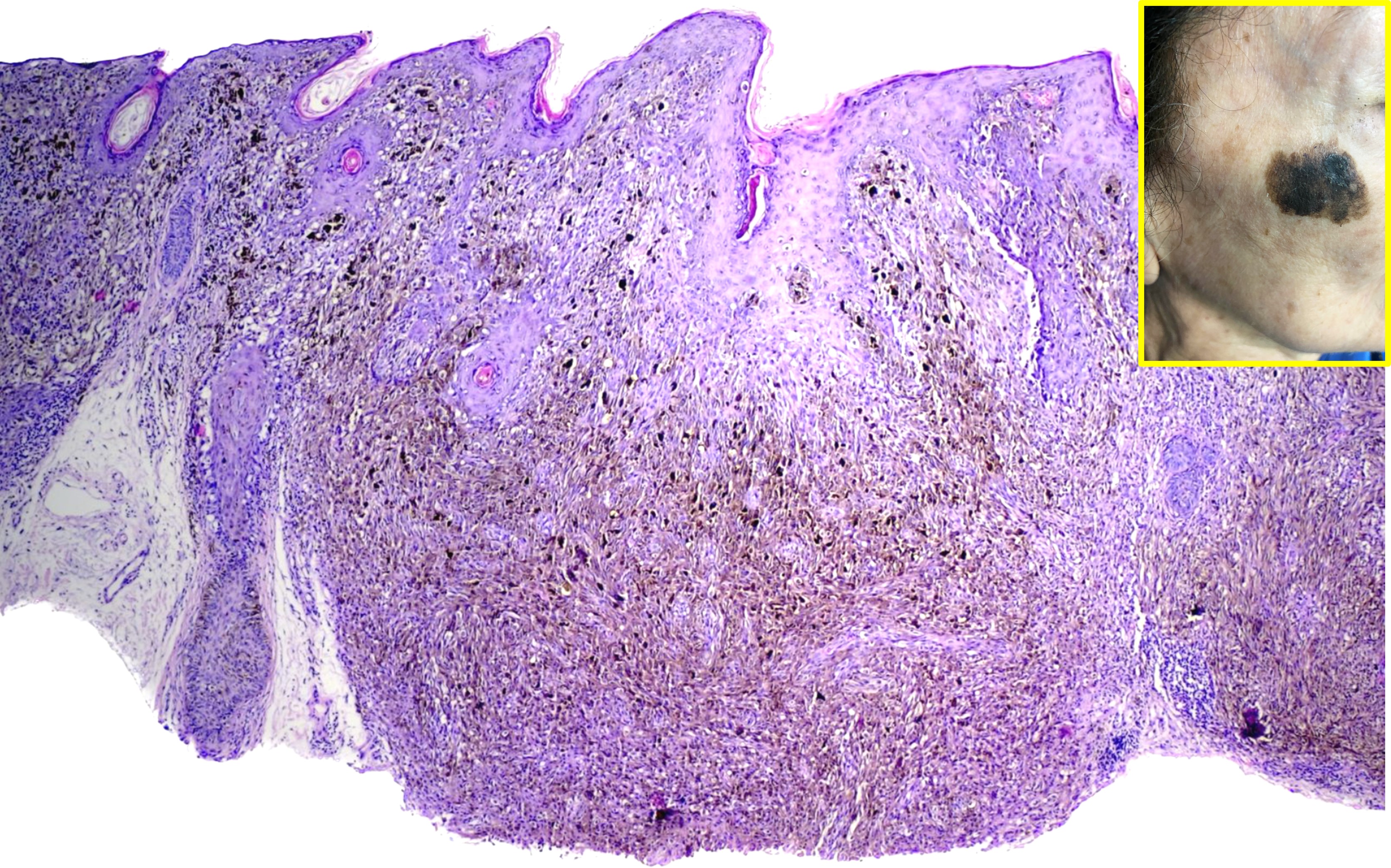

Atypical nevi associated with FAMMM typically exhibit irregular borders, variations in color, and larger size compared to common nevi. These nevi may appear anywhere on the body, but they often manifest on sun-exposed areas such as the back, chest, and limbs. Histologically, these nevi display dysplastic features, including architectural disarray and cytological abnormalities, underscoring their potential for malignant transformation.

A lifelong propensity for the development of melanoma characterizes the natural history of FAMMM syndrome. Individuals affected by this syndrome often experience the emergence of numerous atypical nevi during childhood or adolescence, with the risk of melanoma diagnosis increasing with age. The development of up to 50 primary melanomas has been reported in patients with FAMMM syndrome.[4] Despite heightened surveillance and preventive measures, melanomas arising in the context of FAMMM may exhibit aggressive behavior, contributing to increased morbidity and mortality rates. In addition to melanoma, these patients have an increased risk of developing pancreatic carcinomas as well as other internal malignancies.[5][6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of FAMMM is multifactorial, involving a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental influences. One of the primary causes of FAMMM syndrome is the inheritance of germline mutations in genes associated with melanoma susceptibility. The most commonly implicated genes include CDKN2A and CDK4, although mutations in other genes, such as MITF and TERT, have also been linked to familial melanoma syndromes.[2] The CDKN2A gene is located on locus 9p21 and encodes for p16INK4a and p14ARF proteins.[7] These mutations disrupt the normal regulation of cell growth and proliferation via the cell cycle, leading to an increased risk of melanocyte transformation and the development of melanoma.[8] INK4a mutations can also be associated with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.[9] The inheritance pattern of FAMMM syndrome is typically autosomal dominant, with affected individuals inheriting a mutated copy of the relevant gene from one parent.[4]

While genetic factors play a significant role in predisposing individuals to FAMMM syndrome, environmental exposures also contribute to disease development. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight is a well-established environmental risk factor for melanoma, and individuals with FAMMM syndrome may exhibit increased susceptibility to the carcinogenic effects of UV radiation.[10] Prolonged sun exposure, particularly during childhood and adolescence, can exacerbate the risk of melanoma development in individuals with FAMMM syndrome. Other environmental factors, such as exposure to ionizing radiation and certain chemicals, may also influence disease risk, although their contribution to FAMMM pathogenesis requires further investigation.[11][12][13]

The interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures is thought to play a crucial role in the development of FAMMM syndrome.[14][15] Individuals with germline mutations in melanoma susceptibility genes may exhibit heightened sensitivity to environmental carcinogens, increasing their susceptibility to melanoma development. Conversely, environmental factors, such as UV radiation exposure, may influence the penetrance and expressivity of disease-associated mutations, modulating the clinical phenotype of FAMMM syndrome. Elucidating the complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors is essential for comprehensively understanding FAMMM pathogenesis and developing targeted preventive strategies.

Epidemiology

While precise epidemiological data on FAMMM syndrome are limited, insights gleaned from population-based studies and familial aggregation analyses provide valuable information about the frequency and distribution of this condition.

FAMMM syndrome demonstrates a relatively equal sex distribution, with no significant predilection for either males or females. Both men and women can inherit and manifest the genetic mutations associated with FAMMM syndrome, leading to the development of atypical nevi and an increased risk of melanoma. The comparable prevalence of FAMMM syndrome across sexes underscores the importance of comprehensive surveillance and preventive measures for all individuals with a family history of melanoma or atypical nevi.[16]

FAMMM syndrome can manifest at any age, although the onset of clinical symptoms typically occurs during childhood or adolescence. Affected individuals may present with multiple atypical nevi at a young age, often before the age of 30. The risk of melanoma diagnosis increases with advancing age, with affected individuals exhibiting a lifelong predisposition to melanoma development. Regular dermatologic surveillance is essential for early detection and management of melanoma in individuals with FAMMM syndrome, given the potential for malignant transformation of atypical nevi over time.

FAMMM syndrome has been reported in populations worldwide, although its prevalence may vary across different geographic regions. Population-based studies from countries with predominantly fair-skinned populations, such as the United States, Australia, and European countries, have provided valuable insights into the epidemiology of FAMMM syndrome. However, limited data are available from regions with diverse ethnic populations, highlighting the need for further research to elucidate the global distribution of FAMMM syndrome and its impact on different racial and ethnic groups.[5]

Pathophysiology

FAMMM syndrome is characterized by dysregulated cell growth and proliferation within melanocytes, leading to the development of multiple atypical nevi and increased susceptibility to melanoma. Germline mutations in genes such as CDKN2A and CDK4 disrupt key regulatory pathways involved in cell cycle control and tumor suppression, predisposing affected individuals to malignant transformation.[17][18] Common findings include the presence of numerous dysplastic nevi exhibiting architectural disarray and cytological abnormalities, which serve as precursor lesions for the development of melanoma.[17] Dysfunctional melanocyte signaling pathways, coupled with environmental factors such as UV radiation exposure, contribute to the progressive accumulation of genetic alterations and the eventual onset of melanoma in individuals with FAMMM syndrome.[11]

History and Physical

Patients with FAMMM syndrome may present with a pertinent medical history of multiple atypical nevi, a family history of melanoma, and a personal history of skin cancer. During the physical examination, clinicians typically observe the presence of numerous atypical nevi characterized by irregular borders, variable pigmentation, and larger size compared to common nevi. These nevi may be distributed across sun-exposed areas such as the back, chest, and limbs. Additionally, patients may exhibit features suggestive of prior melanoma, including scarred or excised lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, or signs of metastatic disease. It is important to note that while many patients with CDKN2A mutation have multiple atypical nevi, a significant number do not. CDKN2A mutation carriers may have a variable phenotype; some may present with few nevi but a significant history of cutaneous melanoma.[19] FAMMM has also presented initially with multiple neurofibromas.[20] Due to this variable phenotype, all family members of FAMMM syndrome patients should be considered as potential CDKN2A mutation carriers, regardless of the number of atypical nevi.

Careful examination of the skin, mucous membranes, and lymph nodes is essential for identifying suspicious lesions and assessing disease burden in individuals with FAMMM syndrome. Given the elevated risk of melanoma associated with this condition, regular dermatologic surveillance and comprehensive skin examinations are recommended for early detection and management of cutaneous malignancies.

Evaluation

A thorough dermatologic evaluation is essential for identifying suspicious lesions and assessing disease burden in individuals with FAMMM syndrome. Initial evaluation should also include a thorough personal/family history, including screening for melanoma and pancreatic cancer among first, second, and third-degree relatives.[3] Dermoscopy may aid in the identification of suspicious features associated with melanoma. Atypical nevi should be evaluated via the ABCDE "Asymmetry, Border, Color, Diameter, Evolution) characteristics. Total body photography and sequential digital dermoscopy imaging may also be utilized for longitudinal monitoring of nevi and early detection of changes suggestive of malignant transformation.

Genetic testing for mutations in melanoma susceptibility genes, such as CDKN2A and CDK4, may be indicated in individuals with a strong family history of melanoma or multiple atypical nevi. Identification of pathogenic mutations can facilitate risk stratification, genetic counseling, and targeted surveillance strategies for affected individuals and their family members. In recent years, two statistical models have emerged to help identify CDKN2A-mutation-bearing individuals; these include MELPREDICT and MelaPRO.[17] These models estimate the likelihood of mutation carriage for any given individual or family member based on cancer patterns observed within the family. Despite these available tools, the use of genetic testing for screening remains controversial.[6]

Histopathologic examination of suspicious lesions through biopsy is essential for confirming the diagnosis of melanoma and assessing the degree of dysplasia in atypical nevi. The histologic characteristics of melanoma in FAMMM patients do not differ significantly from those in sporadic melanoma cases.[6]

Imaging studies such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or positron emission tomography (PET) may be utilized for staging and surveillance of melanoma, particularly in cases of suspected metastatic disease.[21] Lymph node mapping with sentinel lymph node biopsy may also be performed to evaluate regional lymph node involvement in individuals with clinically localized melanoma.[22]

Regular follow-up and surveillance are crucial components of the evaluation process for individuals with FAMMM syndrome. Surveillance protocols typically include periodic skin examinations every 6 to 12 months, dermatologic photography, and imaging studies tailored to individual risk factors and disease stage. While established diagnostic guidelines for FAMMM syndrome are lacking, recommendations for surveillance and management are outlined by expert consensus guidelines from organizations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD).[21] These guidelines emphasize the importance of early detection, risk stratification, and multidisciplinary management of individuals at increased risk of melanoma due to FAMMM syndrome.

Treatment / Management

FAMMM syndrome necessitates a multifaceted management approach aimed at mitigating the risk of melanoma development, detecting cutaneous malignancies early, and optimizing patient outcomes. Treatment strategies encompass a combination of surgical, medical, and preventive interventions, guided by established clinical guidelines and expert consensus recommendations.[17][23](B3)

Surgical management plays a central role in the treatment of FAMMM, with excision remaining the cornerstone for both melanoma and atypical nevi. Suspicious lesions undergo surgical excision with appropriate margins to ensure complete removal and minimize the risk of recurrence. Additionally, sentinel lymph node biopsy may be indicated for individuals with clinically localized melanoma to assess regional lymph node involvement and guide further management decisions. In cases of confirmed lymph node metastases, lymphadenectomy may be performed, while wide local excision addresses recurrent or advanced melanoma lesions.[21][22](A1)

Medical management encompasses adjuvant therapy options tailored to individuals with high-risk melanoma features. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, as well as targeted therapies directed against specific molecular aberrations like BRAF inhibitors, have demonstrated efficacy in improving outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma. Systemic surveillance with regular imaging studies may also be recommended for individuals at high risk of melanoma recurrence or metastasis, particularly those with a history of advanced-stage disease or genetic predisposition to melanoma.[23][24][25](B3)

Preventive measures are paramount in FAMMM management, focusing on sun protection, regular surveillance, and genetic counseling. Sun protection measures, including sunscreen use, protective clothing, and sun avoidance during peak hours, are essential for reducing the risk of melanoma development. Regular skin self-examinations and dermatologic surveillance facilitate the early detection of new or changing lesions, enabling prompt evaluation and intervention. Genetic counseling plays a crucial role in educating affected individuals and their families about familial risk factors, inheritance patterns, and the importance of informed decision-making.[17][21]

Established guidelines for melanoma management, such as those from the NCCN and the AAD, provide evidence-based recommendations for treatment and surveillance strategies in individuals with FAMMM syndrome. Multidisciplinary collaboration among dermatologists, oncologists, genetic counselors, and other healthcare providers is essential for delivering comprehensive care and optimizing outcomes in patients with FAMMM syndrome. This integrated approach addresses the complex needs of individuals with FAMMM, emphasizing prevention, early detection, and personalized treatment strategies to mitigate the impact of this hereditary disorder.

Differential Diagnosis

When evaluating patients presenting with suspected familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome (FAMMM), clinicians must consider a range of differential diagnoses to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate management. Among the conditions that may mimic FAMMM are dysplastic nevus syndrome (DNS), other hereditary melanoma syndromes, xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), and other cutaneous malignancies.

DNS shares many clinical characteristics with FAMMM, including the presence of multiple atypical nevi with irregular borders, variable pigmentation, and an increased risk of melanoma. However, DNS typically lacks a strong familial predisposition, and genetic testing may not reveal mutations in melanoma susceptibility genes.

Additionally, other hereditary melanoma syndromes, such as the melanoma-astrocytoma syndrome (MAS) and the BAP1-tumor predisposition syndrome, may present with features overlapping those of FAMMM.[17] These syndromes are characterized by an increased risk of melanoma and other malignancies, often in association with specific genetic mutations. Genetic testing and comprehensive evaluation are essential for distinguishing between different hereditary melanoma syndromes and guiding appropriate management.

Furthermore, xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by impaired DNA repair mechanisms, leading to extreme sensitivity to ultraviolet (UV) radiation and a predisposition to cutaneous malignancies, including melanoma. Patients with XP may present with multiple skin lesions resembling atypical nevi, underscoring the importance of considering this diagnosis in the differential evaluation of FAMMM.

Surgical Oncology

In patients with familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome, the role of surgical oncology primarily centers on the management of cutaneous melanoma, which is the most significant malignancy associated with this condition. Early-stage melanoma remains a surgically curable disease, making timely and accurate surgical intervention essential. For suspicious lesions or confirmed melanomas, wide local excision (WLE) with histologically clear margins is the standard of care. Margin recommendations vary by tumor thickness per NCCN guidelines (eg, 1 cm for melanomas ≤1 mm thick; 2 cm for melanomas >2 mm thick).

The MelMarT-II (Melanoma Margins Trial II) is an ongoing international, multicenter, phase III randomized controlled trial evaluating whether a 1 cm surgical excision margin is as effective as a 2 cm margin in patients with stage II primary cutaneous melanoma. This study aims to determine if narrower margins can provide equivalent disease-free survival while potentially reducing surgical morbidity and improving quality of life. The trial's outcomes may influence future surgical guidelines, particularly benefiting patients with hereditary melanoma syndromes like FAMMM, who often require multiple resections.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is indicated in patients with intermediate-thickness melanomas (>1 mm) or those with high-risk features (eg, ulceration, elevated mitotic rate). SLNB helps stratify prognosis and guide adjuvant therapy decisions. Completion lymph node dissection is no longer routinely performed unless clinically indicated, per findings from MSLT-II (Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial II).

Surgical planning in FAMMM patients can be challenging due to the high number of atypical nevi. Recurrent biopsies and excisions may result in scarring, cosmetic disfigurement, and psychological burden, especially in younger patients. Collaboration with dermatologic surgeons or plastic surgeons may be warranted for lesions in cosmetically sensitive or anatomically complex areas (eg, face, digits).

Emerging data support the integration of systemic therapies such as immunotherapy or BRAF-targeted agents in cases of advanced or unresectable melanoma, often in coordination with surgical teams for potential neoadjuvant or adjuvant use. Ongoing clinical trials are exploring the role of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in resectable stage IIIB–C melanoma, including patients with hereditary melanoma syndromes.

Postoperative complications from melanoma surgery are uncommon but may include seroma, infection, lymphatic leakage, and in rare cases, lymphedema, particularly following SLNB in the groin or axilla. Preventing and managing these adverse effects requires a coordinated effort between surgeons, wound care specialists, nurses, and physical therapists.

Surgical oncologists are integral members of the interprofessional team in FAMMM management, not only in treating melanoma but also in ongoing surveillance and risk-reduction strategies, especially in patients with a personal or family history of multiple or recurrent melanomas.

Prognosis

The prognosis of FAMMM syndrome is variable and depends on several factors, including the extent of disease involvement, the aggressiveness of melanomas, and the effectiveness of treatment and surveillance strategies. Individuals with FAMMM are at a significantly increased risk of developing melanoma compared to the general population, often at a younger age and with multiple primary lesions. Patients with FAMMM syndrome and a CDKN2A mutation have an estimated 50% to 85% risk of developing melanoma during their lifetime.[4]

Early detection and management of melanomas and atypical nevi are critical for improving outcomes in patients with FAMMM. While the majority of melanomas associated with FAMMM are diagnosed at an early stage, some may present with aggressive features, including deep invasion, lymph node involvement, or distant metastasis, leading to a poorer prognosis.

The implementation of comprehensive surveillance protocols, including regular skin examinations, dermatologic photography, and imaging studies, can aid in the early detection of melanomas and facilitate timely intervention. Genetic testing and counseling may also play a crucial role in risk stratification and guiding personalized management approaches for individuals with FAMMM and their family members.

Penetrance for pancreatic cancer in CDKN2A mutation carriers is estimated to be 17% by the age of 75.[6] Cigarette smoking appears to be the primary modifier influencing the risk of pancreatic cancer.[6]

Overall, the prognosis of FAMMM syndrome has improved with advances in early detection, surgical techniques, and adjuvant therapies. However, long-term outcomes remain influenced by factors such as disease stage, tumor biology, and response to treatment. Continued research efforts aimed at elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying FAMMM and identifying novel therapeutic targets are essential for further improving prognosis and outcomes in affected individuals.

Complications

FAMMM syndrome presents various complications primarily arising from the heightened risk of melanoma development and the potential for aggressive disease behavior. Chief among these complications is the increased likelihood of melanoma, significantly elevating the lifetime risk compared to the general population. Melanomas associated with FAMMM may exhibit aggressive features, including rapid growth, deep invasion, lymphatic and hematogenous spread, and resistance to treatment. In FAMMM patients, melanocytic nevi harboring cells with CDKN2A loss of heterozygosity may be at increased risk of developing melanoma.[2]

Moreover, melanomas in individuals with FAMMM syndrome have an augmented propensity for metastasis to regional lymph nodes and distant organs, leading to advanced-stage disease and poorer prognosis. Metastatic melanoma is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, often necessitating aggressive treatment modalities such as systemic therapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy.

Despite appropriate treatment, melanomas in individuals with FAMMM syndrome may recur locally or metastasize to distant sites following initial management, posing challenges in terms of treatment options and prognosis. Recurrent melanoma requires close surveillance and multidisciplinary management strategies.

Beyond the physical manifestations, the diagnosis of FAMMM syndrome and the heightened risk of melanoma can have a profound psychological impact on affected individuals and their families. Fear of disease recurrence, anxiety about surveillance procedures, and concerns about familial inheritance may contribute to psychological distress and reduced quality of life.

While melanoma is the primary concern in FAMMM syndrome, affected individuals may also be at an increased risk of developing other malignancies, including non-melanoma skin cancers and internal malignancies.[26] Mutations in one CDKN2A variant, known as the p16-Leiden variant, may lead to an increased risk of developing pancreatic and esophageal cancer.[7][27][28] The association between FAMMM and pancreatic cancer was first described in 1991 by Lynch and Fusaro.[29] Regular surveillance for secondary malignancies is essential for early detection and timely intervention.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education are vital components in the long-term management of familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome, to empower individuals to actively participate in melanoma prevention and early detection.

Sun protection is the cornerstone of melanoma risk reduction. Patients should be educated on the importance of daily use of broad-spectrum sunscreen with a high SPF, wearing UV-protective clothing, wide-brimmed hats, and sunglasses, and seeking shade during peak ultraviolet exposure hours. Understanding the cumulative effects of UV radiation and its role in melanoma pathogenesis is essential to promote consistent protective behaviors.

Patients should also be instructed on how to perform regular skin self-examinations, focusing on changes in the size, shape, color, or texture of existing nevi and the appearance of new lesions. Clinicians should provide guidance on the "ABCDE" criteria (Asymmetry, Border, Color, Diameter, Evolution) and encourage prompt medical evaluation of any suspicious findings.

Routine dermatologic surveillance is critical for the early detection of melanoma. Patients should be followed by dermatologists experienced in managing FAMMM syndrome. Adjunctive tools such as dermoscopy, total body photography, and serial digital dermoscopy imaging may enhance the accuracy of monitoring atypical nevi.

Genetic counseling should be offered to patients and at-risk family members. Counseling includes education on the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, familial cancer risks, and the role of genetic testing in risk assessment and long-term management.

Promoting healthy lifestyle behaviors—including smoking cessation, balanced nutrition, regular physical activity, and reduced alcohol consumption—can support overall health and potentially reduce cancer risk.

Finally, the psychological impact of living with FAMMM syndrome should not be overlooked. Patients may experience anxiety, fear, or distress related to cancer risk. Access to counseling, mental health services, and peer support groups should be offered as part of comprehensive care.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the presence of numerous clinically atypical nevi and a significantly increased risk of cutaneous melanoma. Individuals with FAMMM typically present with multiple irregularly shaped, variably pigmented moles that require lifelong dermatologic surveillance to facilitate early detection of malignant transformation. Germline mutations in tumor suppressor genes such as CDKN2A and CDK4 are frequently implicated. In addition to melanoma, affected individuals may face an elevated risk of pancreatic and other internal malignancies. Diagnosis involves comprehensive clinical evaluation, detailed family history assessment, genetic testing, and regular full-body skin examinations. Management emphasizes early detection through routine dermatologic monitoring, patient education on sun protection, and genetic counseling for patients and at-risk family members. Treatment of melanoma, if diagnosed, may include surgical excision and, when appropriate, systemic therapies such as immunotherapy or targeted agents.

Optimal care for patients with FAMMM syndrome requires a coordinated interprofessional approach. Physicians lead diagnostic workups and develop surveillance and treatment plans. Advanced practice providers conduct assessments, provide education, and assist with follow-up care. Nurses play a vital role in patient education, direct care, and post-treatment monitoring. Pharmacists contribute expertise in pharmacotherapy, especially in the setting of systemic melanoma treatment. Genetic counselors assess hereditary risk, guide genetic testing, and counsel patients and families. Pathologists and dermatopathologists interpret biopsies, radiologists assist with staging and internal cancer screening, and mental health professionals provide psychosocial support when needed. Social workers may help address barriers to care and access to resources.

Effective interprofessional communication—facilitated through case conferences, tumor boards, and shared electronic records—ensures alignment on surveillance strategies, risk reduction, and long-term follow-up. Ethical considerations, including patient autonomy, confidentiality, and informed decision-making, are central to care delivery. By recognizing the unique contributions of each team member and fostering collaborative care, the healthcare team can improve early detection, support patient-centered management, and reduce morbidity and mortality associated with FAMMM syndrome.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Lynch HT, Shaw TG. Familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome: history, genetics, and heterogeneity. Familial cancer. 2016 Jul:15(3):487-91. doi: 10.1007/s10689-016-9888-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26892865]

Christodoulou E, Nell RJ, Verdijk RM, Gruis NA, van der Velden PA, van Doorn R. Loss of Wild-Type CDKN2A Is an Early Event in the Development of Melanoma in FAMMM Syndrome. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2020 Nov:140(11):2298-2301.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.03.938. Epub 2020 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 32234459]

Onesti MG, Fallico N, Ciotti M, Pacitti F, Lieto P, Clerico R. Management and follow-up of a patient with Familial Atypical Multiple Mole-Melanoma (FAMMM) Syndrome. Il Giornale di chirurgia. 2012 Apr:33(4):132-5 [PubMed PMID: 22668533]

Gu K, Velde RV, Pitz M, Silver S. Recurrent melanoma development in a Caucasian female with CDKN2A+ mutation and FAMMM syndrome: A case report. SAGE open medical case reports. 2020:8():2050313X20936034. doi: 10.1177/2050313X20936034. Epub 2020 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 32953120]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRaj RC, Patil R. Familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome in an adult Indian male-case report and literature review. Indian journal of dermatology. 2015 Mar-Apr:60(2):217. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.152585. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25814760]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRiegert-Johnson DL, Boardman LA, Hefferon T, Roberts M, Eckerle Mize D, Bishop M, Resse E, Sluzevich J. Familial Atypical Multiple Mole Melanoma Syndrome. Cancer Syndromes. 2009:(): [PubMed PMID: 21249757]

van der Wilk BJ, Noordman BJ, Atmodimedjo PN, Dinjens WNM, Laheij RJF, Wagner A, Wijnhoven BPL, van Lanschot JJB. Development of esophageal squamous cell cancer in patients with FAMMM syndrome: Two clinical reports. European journal of medical genetics. 2020 Mar:63(3):103840. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2020.103840. Epub 2020 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 31923587]

Czajkowski R, Placek W, Drewa G, Czajkowska A, Uchańska G. FAMMM syndrome: pathogenesis and management. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2004 Feb:30(2 Pt 2):291-6 [PubMed PMID: 14871223]

Vinarsky V, Fine RL, Assaad A, Qian Y, Chabot JA, Su GH, Frucht H. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in FAMMM syndrome. Head & neck. 2009 Nov:31(11):1524-7. doi: 10.1002/hed.21050. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19360740]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCust AE , Mishra K , Berwick M . Melanoma - role of the environment and genetics. Photochemical & photobiological sciences : Official journal of the European Photochemistry Association and the European Society for Photobiology. 2018 Dec 5:17(12):1853-1860. doi: 10.1039/c7pp00411g. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30113042]

Yoneta A, Yamashita T, Jin HY, Kondo S, Jimbow K. Ectopic expression of tyrosinase increases melanin synthesis and cell death following UVB irradiation in fibroblasts from familial atypical multiple mole and melanoma (FAMMM) patients. Melanoma research. 2004 Oct:14(5):387-94 [PubMed PMID: 15457095]

Chaudru V, Chompret A, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Spatz A, Avril MF, Demenais F. Influence of genes, nevi, and sun sensitivity on melanoma risk in a family sample unselected by family history and in melanoma-prone families. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004 May 19:96(10):785-95 [PubMed PMID: 15150307]

Cust AE, Schmid H, Maskiell JA, Jetann J, Ferguson M, Holland EA, Agha-Hamilton C, Jenkins MA, Kelly J, Kefford RF, Giles GG, Armstrong BK, Aitken JF, Hopper JL, Mann GJ. Population-based, case-control-family design to investigate genetic and environmental influences on melanoma risk: Australian Melanoma Family Study. American journal of epidemiology. 2009 Dec 15:170(12):1541-54. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp307. Epub 2009 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 19887461]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVicente ALSA, Novoloaca A, Cahais V, Awada Z, Cuenin C, Spitz N, Carvalho AL, Evangelista AF, Crovador CS, Reis RM, Herceg Z, de Lima Vazquez V, Ghantous A. Cutaneous and acral melanoma cross-OMICs reveals prognostic cancer drivers associated with pathobiology and ultraviolet exposure. Nature communications. 2022 Jul 15:13(1):4115. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31488-w. Epub 2022 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 35840550]

Yu Y, Hu H, Chen JS, Hu F, Fowler J, Scheet P, Zhao H, Huff CD. Integrated case-control and somatic-germline interaction analyses of melanoma susceptibility genes. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular basis of disease. 2018 Jun:1864(6 Pt B):2247-2254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.01.007. Epub 2018 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 29317335]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFusaro RM, Lynch HT. The FAMMM syndrome: epidemiology and surveillance strategies. Cancer investigation. 2000:18(7):670-80 [PubMed PMID: 11036474]

Soura E, Eliades PJ, Shannon K, Stratigos AJ, Tsao H. Hereditary melanoma: Update on syndromes and management: Genetics of familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2016 Mar:74(3):395-407; quiz 408-10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.038. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26892650]

Hampel H, Bennett RL, Buchanan A, Pearlman R, Wiesner GL, Guideline Development Group, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee and National Society of Genetic Counselors Practice Guidelines Committee. A practice guideline from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors: referral indications for cancer predisposition assessment. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2015 Jan:17(1):70-87. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.147. Epub 2014 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 25394175]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceIpenburg NA, Gruis NA, Bergman W, van Kester MS. The absence of multiple atypical nevi in germline CDKN2A mutations: Comment on "Hereditary melanoma: Update on syndromes and management: Genetics of familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2016 Oct:75(4):e157. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.069. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27646763]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVanneste R, Smith E, Graham G. Multiple neurofibromas as the presenting feature of familial atypical multiple malignant melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2013 Jun:161A(6):1425-31. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35884. Epub 2013 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 23613284]

Swetter SM, Tsao H, Bichakjian CK, Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Elder DE, Gershenwald JE, Guild V, Grant-Kels JM, Halpern AC, Johnson TM, Sober AJ, Thompson JA, Wisco OJ, Wyatt S, Hu S, Lamina T. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019 Jan:80(1):208-250. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.055. Epub 2018 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 30392755]

Wong SL, Faries MB, Kennedy EB, Agarwala SS, Akhurst TJ, Ariyan C, Balch CM, Berman BS, Cochran A, Delman KA, Gorman M, Kirkwood JM, Moncrieff MD, Zager JS, Lyman GH. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy and Management of Regional Lymph Nodes in Melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018 Feb 1:36(4):399-413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.7724. Epub 2017 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 29232171]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCurti BD, Faries MB. Recent Advances in the Treatment of Melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2021 Jun 10:384(23):2229-2240. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2034861. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34107182]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKeung EZ, Gershenwald JE. Clinicopathological Features, Staging, and Current Approaches to Treatment in High-Risk Resectable Melanoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2020 Sep 1:112(9):875-885. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32061122]

Swetter SM, Thompson JA, Albertini MR, Barker CA, Baumgartner J, Boland G, Chmielowski B, DiMaio D, Durham A, Fields RC, Fleming MD, Galan A, Gastman B, Grossmann K, Guild S, Holder A, Johnson D, Joseph RW, Karakousis G, Kendra K, Lange JR, Lanning R, Margolin K, Olszanski AJ, Ott PA, Ross MI, Salama AK, Sharma R, Skitzki J, Sosman J, Wuthrick E, McMillian NR, Engh AM. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Melanoma: Cutaneous, Version 2.2021. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2021 Apr 1:19(4):364-376. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0018. Epub 2021 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 33845460]

Middlebrooks CD, Stacey ML, Li Q, Snyder C, Shaw TG, Richardson-Nelson T, Rendell M, Ferguson C, Silberstein P, Casey MJ, Bailey-Wilson JE, Lynch HT. Analysis of the CDKN2A Gene in FAMMM Syndrome Families Reveals Early Age of Onset for Additional Syndromic Cancers. Cancer research. 2019 Jun 1:79(11):2992-3000. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1580. Epub 2019 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 30967399]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNoë M, Hackeng WM, de Leng WWJ, Vergeer M, Vleggaar FP, Morsink FHM, Wood LD, Hruban RH, Offerhaus GJA, Brosens LAA. Well-differentiated Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor in a Patient With Familial Atypical Multiple Mole Melanoma Syndrome (FAMMM). The American journal of surgical pathology. 2019 Sep:43(9):1297-1302. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001314. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31261289]

Vasen HF, Gruis NA, Frants RR, van Der Velden PA, Hille ET, Bergman W. Risk of developing pancreatic cancer in families with familial atypical multiple mole melanoma associated with a specific 19 deletion of p16 (p16-Leiden). International journal of cancer. 2000 Sep 15:87(6):809-11 [PubMed PMID: 10956390]

Lynch HT, Fusaro RM. Pancreatic cancer and the familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome. Pancreas. 1991 Mar:6(2):127-31 [PubMed PMID: 1886881]