Introduction

Airway management holds paramount importance in operating room and critical care settings. Patients experiencing respiratory distress or requiring general anesthesia frequently need an advanced airway, such as an endotracheal tube or laryngeal mask airway, to facilitate ventilatory support. Failure to secure the airway during intubation may result in catastrophic, potentially fatal outcomes. Several assessment tools assist proceduralists in anticipating challenges during airway management.[1] This activity focuses on the Mallampati score, a simple and rapid tool enabling proceduralists to evaluate airway anatomy and predict potential difficulties during airway manipulation.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The human airway functions to permit airflow during spontaneous and mechanical ventilation. The airway is divided into 2 main portions: the upper and lower airways. The upper airway includes the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx. The lower airway is comprised of the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli. The larynx separates the upper and lower airways and plays a key role in sound production, containing 2 fundamental structures, the epiglottis and vocal cords.[2]

During endotracheal intubation, the proceduralist guides the endotracheal tube through the upper airway and vocal cords into the trachea. In orotracheal intubation, the tube passes through oropharyngeal structures, including the base of the tongue, palatine tonsils, tonsillar pillars, and uvula. Enlarged oropharyngeal structures may complicate laryngoscopy and intubation.

The Mallampati score assesses the relative size of the tongue base in relation to the oropharyngeal opening to predict potential airway difficulty. This classification helps clinicians anticipate challenges during intubation and plan appropriate airway management strategies.

Indications

The Mallampati score is used when a patient requires anesthesia or intubation. This assessment assists the proceduralist in anticipating airway anatomy challenges before securing the airway.

Contraindications

This assessment tool has no absolute contraindications. However, the score’s usefulness diminishes if the patient cannot fully cooperate during the examination. Certain pathologies, such as head and neck infections, cancers, inflammatory or infectious laryngeal conditions (eg, epiglottitis), Ludwig angina, goiter, and facial trauma, may contribute to a difficult airway that the Mallampati score cannot accurately predict.

Personnel

The Mallampati score may be performed by a single trained clinician, such as a physician or advanced practice provider, responsible for airway management. Proper training ensures these clinicians perform the assessment accurately, enhancing airway management outcomes.

Preparation

Induction of anesthesia marks a critical period during which sedation medications reduce respiratory drive. Following induction, the proceduralist must maintain oxygenation and ventilation by either mask ventilation or placement of an advanced airway, such as an endotracheal tube or laryngeal mask airway. While most patients allow straightforward mask ventilation and intubation, approximately 1% to 5% of patients present difficulty with mask ventilation and around 5% with intubation.[3][4][5][6]

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Practice Guidelines define difficult mask ventilation as the inability to ventilate, confirmed by end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring. Difficult intubation involves multiple intubation attempts or failure to secure the airway after repeated efforts.[7]

A closed claim analysis revealed that 67% of difficult airway-related claims occurred during anesthesia induction. Anticipating and preparing for patients with potential difficulties in mask ventilation or intubation can help prevent these adverse outcomes.[8]

Technique or Treatment

Over time, numerous risk factors have been proposed to assist proceduralists in predicting and preparing for potential challenges during anesthesia induction. Among these clinical tools, the Mallampati score remains a widely utilized assessment tool. In 1983, Dr. Seshagiri Mallampati, an anesthesiologist, postulated that the size of the tongue base relative to the oropharyngeal cavity could serve as a predictor of difficult intubation.[9]

A relatively large tongue obscures the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches and the uvula, whereas a smaller tongue permits visualization of these structures. To evaluate this hypothesis, Dr. Mallampati conducted a study involving 210 healthy adults undergoing direct laryngoscopy, performing preoperative assessments of the relative tongue size in relation to the oropharyngeal space.

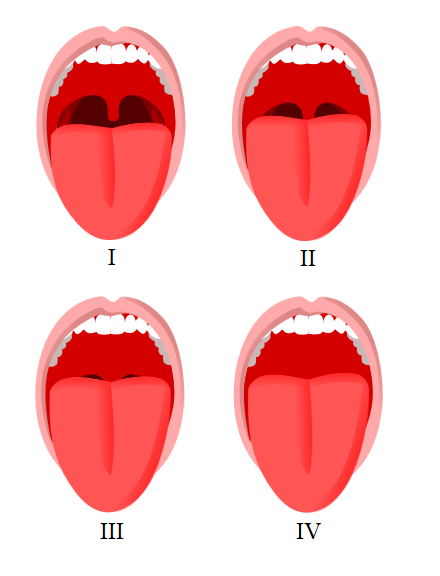

Participants were seated and instructed to open their mouths fully and protrude the tongue maximally without phonation. Based on the structures visible during this examination, patients were classified into 3 distinct classes as follows:

- Class I: Complete visualization of the faucial pillars, soft palate, and uvula

- Class II: Visualization of the faucial pillars and soft palate, with the uvula obscured by the tongue base

- Class III: Visualization limited to the soft palate alone

Dr. Mallampati defined difficult intubation as inadequate exposure of the glottis during direct laryngoscopy. His findings demonstrated a significant correlation between this clinical assessment, currently known as the Mallampati score, and the incidence of intubation difficulty.[10]

Just 2 years after the original publication, Samson and Young introduced a 4th classification, now known as Mallampati Class IV, in which the faucial pillars, uvula, and soft palate are all obscured from view (see Image. Mallampati Score Classification). In the researchers' study of obstetric patients, all 7 cases of difficult intubation corresponded to Mallampati Class III or IV.[11]

In 1998, Class 0 was added to describe the rare occurrence of epiglottic visibility during pharyngoscopic examination. This classification correlated with consistently easy endotracheal intubation.[12][13] These findings contributed to the broader clinical acceptance of the Mallampati scoring system as a rapid, practical method for anticipating and preparing for potential difficult intubation.

The modified Mallampati score routinely used today is as follows:

- Class 0: Epiglottis partially or fully visible

- Class I: Full view of soft palate, uvula, and tonsillar pillars

- Class II: Soft palate and uvula visible, pillars obscured

- Class III: Soft palate and uvula base visible

- Class IV: Visualization restricted to the hard palate

To properly perform the modified Mallampati score, the patient should be seated upright, open the mouth fully, and maximally protrude the tongue. Traditionally, this examination is performed without phonation.

The extended Mallampati score is assessed with the patient seated, the craniocervical junction extended, and the mouth held open while the tongue is protruded without phonation. A study demonstrated that the extended Mallampati score offers greater sensitivity and specificity than the modified Mallampati score in predicting difficult intubation during direct laryngoscopy.[14]

Clinical Significance

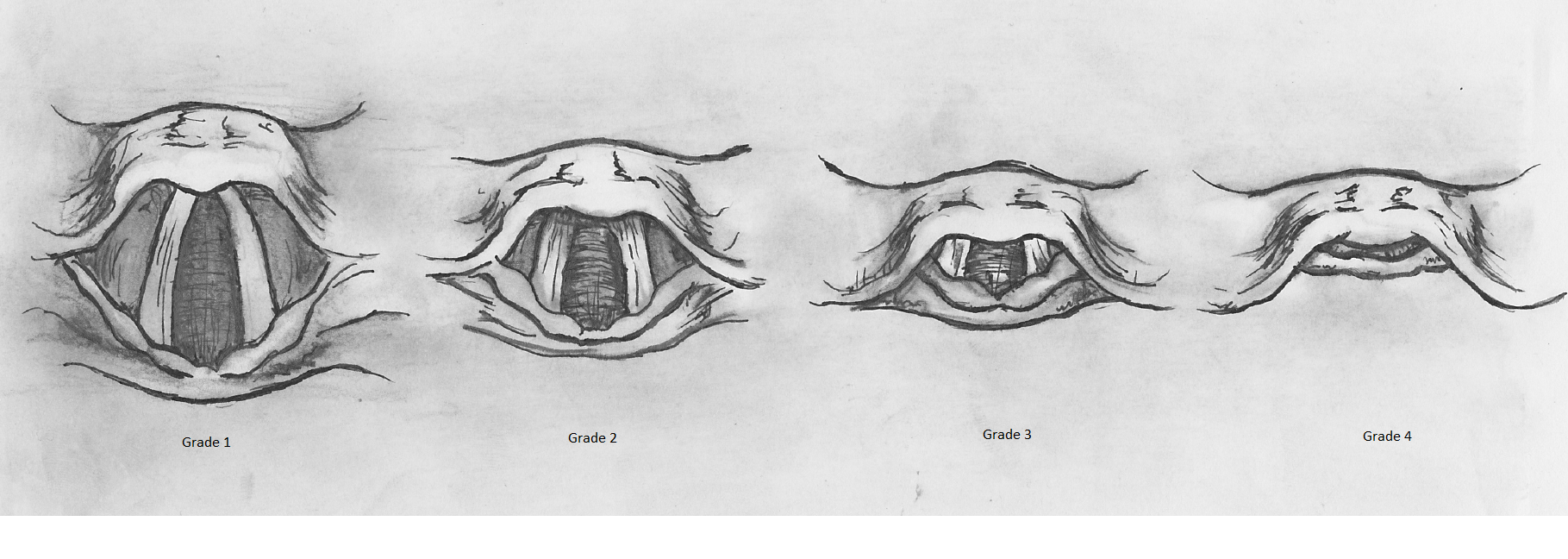

Since its introduction in the 1980s, the Mallampati scoring system has rapidly become a standard component of the preoperative physical examination to predict difficult airway management. Early studies suggested that Classes III and IV correlated with difficult intubation based on laryngeal views described in the original study. However, these laryngeal views differed from the Cormack-Lehane grading system, introduced a year later and now widely adopted for airway assessment (see Image. Cormack-Lehane Grading System).[15]

Some researchers have argued that many views classified as "difficult" by Mallampati correspond to favorable views under the Cormack-Lehane system. In this context, the positive predictive value of the Mallampati score was reported to be as low as 33.3%, indicating limited reliability in predicting difficult intubation.[16] Another study reported a positive predictive value of 22% for Mallampati Class III.[17] A recent meta-analysis further confirmed that, when used in isolation, the Mallampati score exhibits limited accuracy for predicting difficult airway management.[18]

A 2016 Cochrane meta-analysis reported that the modified Mallampati test demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.51 and a specificity of 0.87 for predicting difficult tracheal intubation. These findings indicate that the Mallampati score is a poor standalone screening tool, as it fails to identify nearly half of all difficult airways, though it offers moderate specificity for ruling out difficult intubation.[19]

Additional risk factors associated with difficult endotracheal intubation include a thick neck (>40 cm), limited neck mobility, restricted mouth opening (<3 finger breadths), a short thyromental distance (<6 cm), limited mandibular protrusion, and a documented history of difficult airway management. Proceduralists should evaluate these factors during preoperative assessment and incorporate them into airway planning. Standard preoperative evaluation protocols routinely include documentation of such features to aid in stratifying patients according to airway difficulty risk.

Effective mask ventilation is a critical component of airway management. Inability to ventilate can result in severe complications, and the success or failure of mask ventilation determines subsequent steps in the difficult airway algorithm. As such, anticipating difficulties in mask ventilation is essential for appropriate preparation and clinical decision-making.

Numerous risk factors have been investigated for their utility in predicting difficult mask ventilation. These risk factors include advanced age (>55 years), obesity (body mass index >30 kg/m²), presence of a beard, edentulism, history of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) or snoring, male sex, limited mandibular protrusion, short thyromental distance (<6 cm), and Mallampati class III or IV. A large meta-analysis reported that the Mallampati score has very low sensitivity (0.17) for predicting difficult mask ventilation. Accordingly, as with predicting a difficult intubation, the Mallampati score is an unreliable screening tool when used in isolation.

Notably, the Mallampati score has been shown to vary during pregnancy. In a study involving 242 pregnant individuals, the proportion classified as Mallampati grade IV increased by 34% at 38 weeks of gestation compared to the same cohort at 12 weeks. This rise is commonly attributed to pregnancy-related fluid retention and soft tissue edema.[20] Although overall intubation difficulty is not significantly higher in the pregnant population, the Mallampati score can increase significantly as gestation progresses.[21]

A correlation has also been established between the Mallampati score and OSA, the most prevalent sleep-related breathing disorder. OSA results from upper airway collapse during sleep due to decreased muscle tone. The Mallampati score has been identified as an independent predictor of both the presence and severity of OSA. The odds of having OSA double for every 1-point increase in the Mallampati class, and the apnea-hypopnea index rises by more than 5 events per hour on average.[22] As such, Mallampati assessment may be useful in outpatient clinical settings to help identify patients at risk for OSA prior to polysomnographic evaluation.

Multiple methods, including the Mallampati scoring system, have been proposed to aid in predicting difficult intubation and mask ventilation. However, evidence from this review demonstrates that the Mallampati score alone lacks sufficient sensitivity for identifying patients with challenging airways. As such, reliance on this tool in isolation is not advised. Instead, the Mallampati score should be interpreted in conjunction with other clinical indicators to inform airway management planning. Predicting a difficult airway remains a significant clinical challenge. A recent study reported that 93% of difficult intubations and 94% of difficult mask ventilation cases were unanticipated.[23] Given this uncertainty, proceduralists must maintain vigilance and remain prepared for unforeseen airway complications in all clinical contexts.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Knowledge of the risk factors for difficult mask ventilation and intubation enables physicians and advanced practitioners who routinely perform endotracheal intubation to prepare effectively and secure challenging airways. Involving additional healthcare team members, such as physicians, nurse anesthetists, anesthesia assistants, nursing staff, and respiratory therapists, can support the proceduralist during mask ventilation and intubation.

When intubating a patient known to have a difficult airway, the most experienced provider should perform the initial attempt, since multiple attempts can contribute to airway edema and reduce the likelihood of success. Maintaining adequate oxygenation and ventilation is essential to prevent adverse and potentially fatal outcomes.

Although the Mallampati score serves as a risk factor for difficult mask ventilation and intubation, this score alone cannot reliably predict airway difficulty. Combining the Mallampati score with other established risk factors optimizes airway management strategies.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Mallampati Score Classification. This image shows the visual differences in oropharyngeal anatomy used to assign Mallampati classes during airway assessment.

Jmarchn, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mouri M, Krishnan S, Hendrix JM, Maani CV. Airway Assessment. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262092]

Ball M, Hossain M, Padalia D. Anatomy, Airway. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083624]

Langeron O, Masso E, Huraux C, Guggiari M, Bianchi A, Coriat P, Riou B. Prediction of difficult mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2000 May:92(5):1229-36 [PubMed PMID: 10781266]

Kheterpal S, Han R, Tremper KK, Shanks A, Tait AR, O'Reilly M, Ludwig TA. Incidence and predictors of difficult and impossible mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2006 Nov:105(5):885-91 [PubMed PMID: 17065880]

Shiga T, Wajima Z, Inoue T, Sakamoto A. Predicting difficult intubation in apparently normal patients: a meta-analysis of bedside screening test performance. Anesthesiology. 2005 Aug:103(2):429-37 [PubMed PMID: 16052126]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLundstrøm LH, Møller AM, Rosenstock C, Astrup G, Wetterslev J. High body mass index is a weak predictor for difficult and failed tracheal intubation: a cohort study of 91,332 consecutive patients scheduled for direct laryngoscopy registered in the Danish Anesthesia Database. Anesthesiology. 2009 Feb:110(2):266-74. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318194cac8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19194154]

Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Connis RT, Abdelmalak BB, Agarkar M, Dutton RP, Fiadjoe JE, Greif R, Klock PA, Mercier D, Myatra SN, O'Sullivan EP, Rosenblatt WH, Sorbello M, Tung A. 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2022 Jan 1:136(1):31-81. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34762729]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePeterson GN, Domino KB, Caplan RA, Posner KL, Lee LA, Cheney FW. Management of the difficult airway: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2005 Jul:103(1):33-9 [PubMed PMID: 15983454]

Mallampati SR. Clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation (hypothesis). Canadian Anaesthetists' Society journal. 1983 May:30(3 Pt 1):316-7 [PubMed PMID: 6336553]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD, Desai SP, Waraksa B, Freiberger D, Liu PL. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Canadian Anaesthetists' Society journal. 1985 Jul:32(4):429-34 [PubMed PMID: 4027773]

Samsoon GL, Young JR. Difficult tracheal intubation: a retrospective study. Anaesthesia. 1987 May:42(5):487-90 [PubMed PMID: 3592174]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEzri T, Cohen I, Geva D, Szmuk P. Pharyngoscopic views. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1998 Sep:87(3):748 [PubMed PMID: 9728878]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEzri T, Warters RD, Szmuk P, Saad-Eddin H, Geva D, Katz J, Hagberg C. The incidence of class "zero" airway and the impact of Mallampati score, age, sex, and body mass index on prediction of laryngoscopy grade. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2001 Oct:93(4):1073-5, table of contents [PubMed PMID: 11574386]

Safavi M, Honarmand A, Amoushahi M. Prediction of difficult laryngoscopy: Extended mallampati score versus the MMT, ULBT and RHTMD. Advanced biomedical research. 2014:3():133. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.133270. Epub 2014 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 24949304]

Cormack RS, Lehane J. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 1984 Nov:39(11):1105-11 [PubMed PMID: 6507827]

O'Leary AM, Sandison MR, Roberts KW. History of anesthesia; Mallampati revisited: 20 years on. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 2008 Apr:55(4):250-1. doi: 10.1007/BF03021512. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18378973]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTse JC, Rimm EB, Hussain A. Predicting difficult endotracheal intubation in surgical patients scheduled for general anesthesia: a prospective blind study. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1995 Aug:81(2):254-8 [PubMed PMID: 7618711]

Lee A, Fan LT, Gin T, Karmakar MK, Ngan Kee WD. A systematic review (meta-analysis) of the accuracy of the Mallampati tests to predict the difficult airway. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2006 Jun:102(6):1867-78 [PubMed PMID: 16717341]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRoth D, Pace NL, Lee A, Hovhannisyan K, Warenits AM, Arrich J, Herkner H. Airway physical examination tests for detection of difficult airway management in apparently normal adult patients. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 May 15:5(5):CD008874. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008874.pub2. Epub 2018 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 29761867]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePilkington S, Carli F, Dakin MJ, Romney M, De Witt KA, Doré CJ, Cormack RS. Increase in Mallampati score during pregnancy. British journal of anaesthesia. 1995 Jun:74(6):638-42 [PubMed PMID: 7640115]

McDonnell NJ, Paech MJ, Clavisi OM, Scott KL, ANZCA Trials Group. Difficult and failed intubation in obstetric anaesthesia: an observational study of airway management and complications associated with general anaesthesia for caesarean section. International journal of obstetric anesthesia. 2008 Oct:17(4):292-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2008.01.017. Epub 2008 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 18617389]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNuckton TJ, Glidden DV, Browner WS, Claman DM. Physical examination: Mallampati score as an independent predictor of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2006 Jul:29(7):903-8 [PubMed PMID: 16895257]

Nørskov AK, Rosenstock CV, Wetterslev J, Astrup G, Afshari A, Lundstrøm LH. Diagnostic accuracy of anaesthesiologists' prediction of difficult airway management in daily clinical practice: a cohort study of 188 064 patients registered in the Danish Anaesthesia Database. Anaesthesia. 2015 Mar:70(3):272-81. doi: 10.1111/anae.12955. Epub 2014 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 25511370]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence