Introduction

Over 15% of the population reports experiencing a severe, debilitating headache. Headaches are ranked the 10th most common health problem and the first most common nervous system disorder. Approximately 1.4% to 2.2% of the global population experiences headaches at least 15 days per month.[1] This painful disorder can reduce the quality of life and is associated with a large socioeconomic burden.[2][3] For this reason, managing headache pain is becoming an increasingly popular topic among specialists.

The greater occipital nerve (GON) block is gaining interest among healthcare professionals as a treatment option for headaches. The GON traverses the upper neck and posterior occiput. Dysfunction of the nerve is associated with several commonly encountered headaches, including classic migraine, occipital neuralgia, cervicogenic, and cluster headache. The GON block can achieve significant analgesia as a primary treatment for headaches and can also be used as a second-line treatment when other methods have been unsuccessful. Symptom improvement frequently varies from patient to patient and can be difficult to predict.[4]

When a GON block is successful, pain typically improves after 20 to 30 minutes and lasts for several hours to several months. For patients experiencing severe or frequent headaches, this treatment can significantly improve their quality of life. If more than 3 nerve blocks are required within 6 months, a provider should explore additional, alternative treatment options.[5]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Peripheral nerve blocks such as the GON block can be a safe and effective pain treatment modality when performed by a clinician with adequate knowledge of head and neck anatomy.[6] Three occipital nerves arise from C2 and C3 spinal nerves and innervate the posterior scalp. The 3 occipital nerves include the GON, the lesser occipital nerve, and the third occipital nerve.[7]

The GON is the largest of the 3 occipital nerves, innervating the posterior scalp. The GON sensory fibers arise from the dorsal primary ramus of the C2 spinal nerve and then ascend through the fascial plane between the obliquus capitis inferior and semispinalis capitis. The fibers pierce the semispinalis capitis and travel deep to the trapezius muscle until exiting the aponeurosis inferior to the superior nuchal line. At this location, the occipital nerve lies subcutaneously and just medial to the occipital artery. This torturous path can potentially lead to nerve irritation and compression.[8]

The frequent cooccurrence of neck pain and headache can also be attributed to the GON and its direct role in the trigeminocervical complex.[9] The C2 sensory neurons of the GON share common sensory innervation with the trigeminal nucleus caudalis, creating a common nociceptive pathway between the head and neck. This continuum between the trigeminal and cervical fibers allows the greater occipital nerve block to represent a reasonable option for acute treatment and prevention of primary and secondary headaches.[5]

Indications

Nerve blocks targeting the GON can be used as a primary treatment for headaches, but are more often used to treat intractable headaches when other methods have failed.[10] The GON block can be an effective and safe treatment option for several headache disorders, including occipital neuralgia, migraine, postdural puncture headache, cervicogenic headache, and cluster headache.[5] The nerve block can also reduce associated symptoms of nerve irritation, including tinnitus and otalgia.[11] Patients who report allodynia of the scalp and those who have reproducible pain with palpation of the GON are most likely to achieve the desired analgesic response after treatment. The GON block is also a viable treatment option for headaches in the elderly and pregnant population who have comorbidities that prevent them from receiving other first-line treatment regimens.[12]

Contraindications

The GON block is generally a well-tolerated, low-risk procedure. Absolute contraindications include patient refusal, anesthetic allergy, open skull defect, and infection at the procedure site. Performing this nerve block at a surgical site is also contraindicated due to the risk of intracranial infiltration.[7]

Other relative contraindications that should be considered before performing the procedure include:

- Coagulopathy

- History of Arnold Chiari malformation [13]

- Inability to lie still in a prone or sitting position

Equipment

The GON block can be performed relatively quickly, easily, and inexpensively. Only minimal equipment is required. The clinician has the option to inject an anesthetic alone or may also choose to inject a combination of an anesthetic and a steroid. Study results suggest no difference in short and long-term migraine pain control when the anesthetic is injected alone or in combination with a steroid. In contrast, the addition of steroids is very effective for treating cluster, cervicogenic, and postdural puncture headaches.[14]

Required equipment for a single GON block includes:

- 5-cc syringe

- 25-gauge needle

- Povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine

- Anesthetic

- Lidocaine 2% (2 mL)

- Bupivacaine 0.5% (2 mL)

- Anti-inflammatory

- Methylprednisolone 40 mg/mL (2 mL)

- Dexamethasone 2 mg/mL (2 mL)

The total injection volume should not exceed 4 mL. If lidocaine and bupivacaine are combined, the ratio should be 1:1 to 1:3.[5][7]

Personnel

A GON block should be performed by a medical professional who has knowledge of head and neck anatomy and has been trained in local anesthesia. A nurse or nursing assistant can assist with patient positioning. Nurses can also help monitor vital signs and watch for signs and symptoms associated with adverse reactions.

Preparation

The clinician should obtain written informed consent from the patient or their decision-making proxy before performing the GON block. Once the risks and benefits have been explained, the patient should be placed in an examination room on a monitor. All necessary equipment and medications should be available at the bedside.

Technique or Treatment

The GON block can be performed unilaterally or bilaterally. However, no method has been identified as superior to the other.[15]

The following steps will discuss how to perform the GON block:

- Optimally position the patient by placing them in a seated or prone position with the neck slightly flexed.

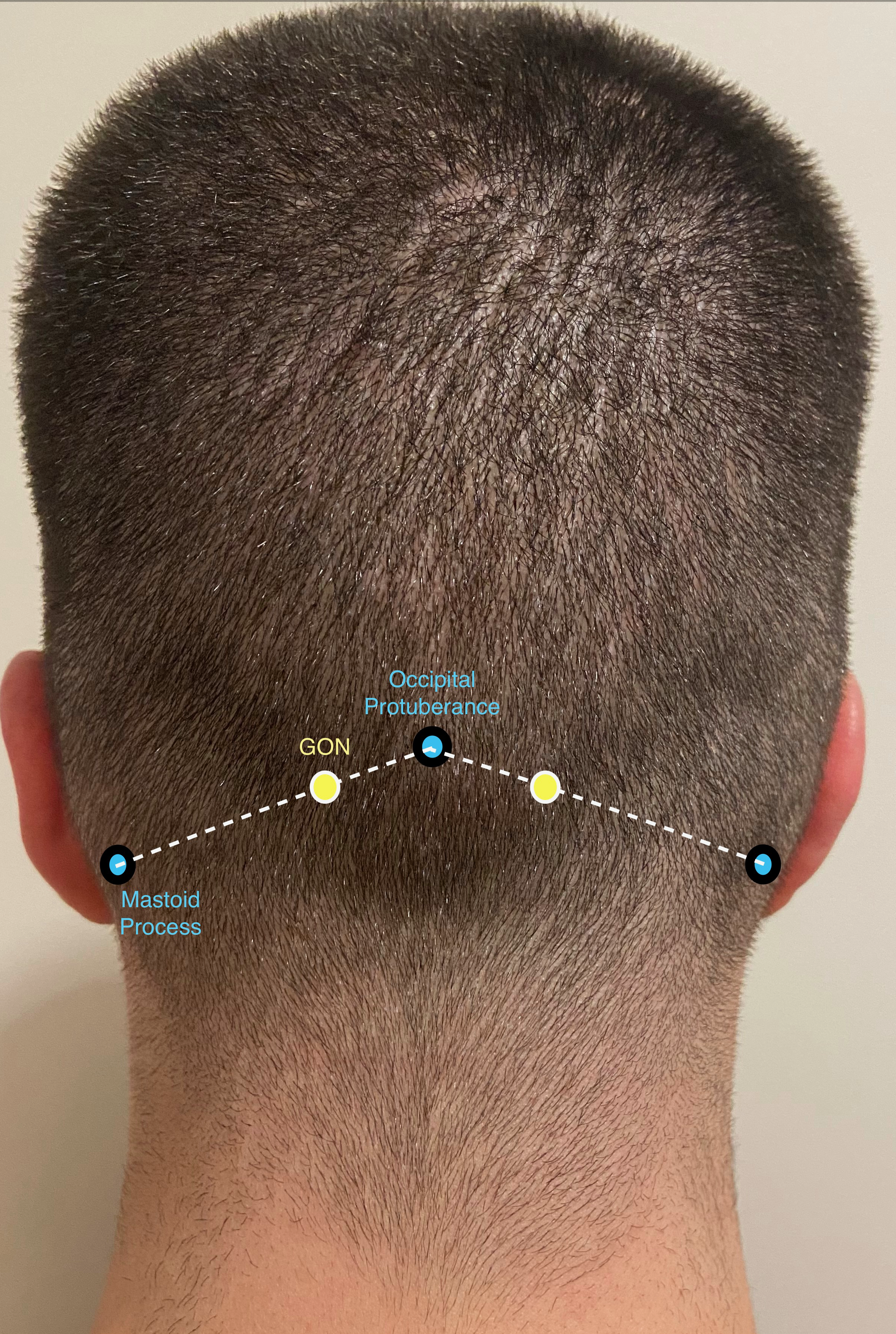

- Palpate the back of the skull to identify the occipital protuberance and the mastoid process on the side of the head where the patient is experiencing the majority of their pain.

- Locate the location of the GON. The location of the GON is approximately one-third of the distance from the occipital protuberance to the mastoid process (see Image. Greater Occipital Nerve Block Anatomy). This location should be approximately 2 cm inferior and 2 cm lateral from the protuberance.

- Cleanse this area using povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine.

- Obtain a syringe filled with the anesthetic. Use an inferior-lateral approach to insert the needle toward the GON. Gently advance the needle tip until resistance is appreciated, indicating contact with the periosteum.

- Withdraw the needle approximately 1 mm and aspirate to ensure the needle is not in contact with the occipital artery.

- Inject an anesthetic in a fan-like distribution. The clinician may also elect to inject an anesthetic directly without fanning distribution.

- Withdraw the needle and apply pressure for 5 to 10 minutes.[5]

Notably, the response to the GON block commonly varies from patient to patient, and the outcome can be challenging to predict. When a GON block is successful, pain typically improves after 20 to 30 minutes and can last for several hours to several months.

Complications

The GON block is an overall safe procedure. Most adverse effects are mild and transient. The most commonly encountered adverse effects include pain, redness, and swelling at the injection site. Other common symptoms that may occur after injection include dizziness, vertigo, numbness, and lightheadedness. Patients may also experience vasovagal syncope, presyncope, facial edema, worsening headache, transient dysphagia, nerve trauma, arterial injury, infection, hematoma, and worsening headache. If a steroid is used, patients may also experience alopecia at the injection site.[5]

Only a small amount of anesthetic is used for the GON block. However, prevention and early identification of lidocaine toxicity must always be addressed. Additional adverse reactions related to lidocaine or bupivacaine toxicity include methemoglobinemia, hypotension, seizures, and cardiac dysrhythmias. The risk of complications can be reduced by aspirating before injecting an anesthetic and communicating with the patient after the nerve block is completed to identify and address new symptoms.[16]

Clinical Significance

Headache is a common and often debilitating presenting complaint across all age groups and medical specialties, significantly impacting patients' quality of life and contributing to a substantial socioeconomic burden through increased healthcare utilization, lost productivity, and disability. Given the prevalence and severity of headache-related disorders, effective and accessible treatment strategies are critical. The GON block is a clinically significant intervention that offers both diagnostic and therapeutic benefits in the management of various headache syndromes, including occipital neuralgia, cervicogenic headaches, and certain types of migraines. By targeting the sensory fibers of the C2 distribution, the block interrupts pain transmission, often resulting in rapid and sustained relief.

The GON block is a low-risk, minimally invasive procedure that requires minimal equipment and can be safely performed in outpatient settings, even in patients with multiple comorbidities. This treatment is an especially valuable option for reducing dependence on systemic medications, such as opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories. This procedure can be used as a standalone therapy or in combination with oral or intravenous pain regimens to enhance clinical outcomes. In chronic headache sufferers, it may break the cycle of pain and facilitate better responses to other therapies. This procedure's simplicity, safety profile, and effectiveness make the GON block essential in modern, multidisciplinary headache management.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective implementation of a GON block requires a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to ensure patient-centered care and optimal outcomes. Clinicians must possess strong anatomical knowledge, procedural skills, and clinical judgment to identify candidates for the block accurately, perform the procedure safely, and assess its therapeutic impact. Nurses play a crucial role in pre- and postprocedural care, encompassing patient education, monitoring for adverse reactions, and facilitating recovery. Pharmacists contribute by ensuring the correct medication selection, accurate dosage, and awareness of potential drug interactions, particularly with corticosteroids or local anesthetics used during the block.

Interprofessional communication and care coordination are essential throughout the patient journey. Clinicians must collaborate to align on treatment goals, document procedural outcomes, and coordinate follow-up care, particularly in patients with complex headache syndromes. Incorporating input from physical therapists, neurologists, and pain specialists may enhance comprehensive management and address underlying biomechanical or neurologic contributors to pain. This team-based strategy improves safety and efficiency, fosters continuity of care, increases patient satisfaction, and advances the overall quality of headache management.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mungoven TJ, Henderson LA, Meylakh N. Chronic Migraine Pathophysiology and Treatment: A Review of Current Perspectives. Frontiers in pain research (Lausanne, Switzerland). 2021:2():705276. doi: 10.3389/fpain.2021.705276. Epub 2021 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 35295486]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHasırcı Bayır BR, Gürsoy G, Sayman C, Yüksel GA, Çetinkaya Y. Greater occipital nerve block is an effective treatment method for primary headaches? Agri : Agri (Algoloji) Dernegi'nin Yayin organidir = The journal of the Turkish Society of Algology. 2022 Jan:34(1):47-53. doi: 10.14744/agri.2021.32848. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34988960]

VanderPluym JH, Charleston L 4th, Stitzer ME, Flippen CC 2nd, Armand CE, Kiarashi J. A Review of Underserved and Vulnerable Populations in Headache Medicine in the United States: Challenges and Opportunities. Current pain and headache reports. 2022 Jun:26(6):415-422. doi: 10.1007/s11916-022-01042-w. Epub 2022 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 35347652]

Afridi SK, Shields KG, Bhola R, Goadsby PJ. Greater occipital nerve injection in primary headache syndromes--prolonged effects from a single injection. Pain. 2006 May:122(1-2):126-9 [PubMed PMID: 16527404]

Chowdhury D, Datta D, Mundra A. Role of Greater Occipital Nerve Block in Headache Disorders: A Narrative Review. Neurology India. 2021 Mar-Apr:69(Supplement):S228-S256. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.315993. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34003170]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHarbell MW, Bolton PB, Koyyalamudi V, Seamans DP, Langley NR. Evaluating the Anatomic Spread of Selective Nerve Scalp Blocks Using Methylene Blue: A Cadaveric Analysis. Journal of neurosurgical anesthesiology. 2023 Apr 1:35(2):248-252. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000826. Epub 2021 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 34882105]

Fernandes L, Randall M MD FRCP, Idrovo L DMed FRCP. Peripheral nerve blocks for headache disorders. Practical neurology. 2020 Oct 23:():. pii: practneurol-2020-002612. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2020-002612. Epub 2020 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 33097609]

Li J, Szabova A. Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blocks in the Head and Neck for Chronic Pain Management: The Anatomy, Sonoanatomy, and Procedure. Pain physician. 2021 Dec:24(8):533-548 [PubMed PMID: 34793642]

Terrier LM, Fontaine D. Intracranial nociception. Revue neurologique. 2021 Sep:177(7):765-772. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2021.07.012. Epub 2021 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 34384629]

Tepper SJ, Stillman MJ. Cluster headache: potential options for medically refractory patients (when all else fails). Headache. 2013 Jul-Aug:53(7):1183-90. doi: 10.1111/head.12148. Epub 2013 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 23808603]

Skinner C, Kumar S. Ultrasound-Guided Occipital Nerve Blocks to Reduce Tinnitus-Associated Otalgia: A Case Series. A&A practice. 2022 Jan 5:16(1):e01552. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000001552. Epub 2022 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 34989354]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceXavier J, Pinho S, Silva J, Nunes CS, Cabido H, Fortuna R, Araújo R, Lemos P, Machado H. Postdural puncture headache in the obstetric population: a new approach? Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2020 May:45(5):373-376. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2019-101053. Epub 2020 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 32094239]

Pincherle A, Bolyn S. Cerebellar syndrome after occipital nerve block: A case report. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache. 2020 Sep:40(10):1123-1126. doi: 10.1177/0333102420929015. Epub 2020 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 32447975]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrandt RB, Doesborg PGG, Meilof R, de Coo IF, Bartels E, Ferrari MD, Fronczek R. Repeated greater occipital nerve injections with corticosteroids in medically intractable chronic cluster headache: a retrospective study. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2022 Feb:43(2):1267-1272. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05399-5. Epub 2021 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 34159486]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKaraoğlan M, Durmuş İE, Küçükçay B, Takmaz SA, İnan LE. Comparison of the clinical efficacy of bilateral and unilateral GON blockade at the C2 level in chronic migraine. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2022 May:43(5):3297-3303. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05739-5. Epub 2021 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 34791570]

McMahon K, Paster J, Baker KA. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity in the pediatric patient. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2022 Apr:54():325.e3-325.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.10.021. Epub 2021 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 34742600]