Introduction

Tobacco use is rapidly increasing globally, with cigarette smoking being the leading cause of death and preventable disease in the United States (US).[1] Smokeless tobacco, as well as electronic cigarettes, have been promoted as an alternative to cigarette smoking.[2] However, smokeless tobacco contains various chemical carcinogens, including tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines such as N′-nitrosonornicotine, which are associated with cancers of the oral cavity, esophagus, and stomach.[3] Smokeless tobacco refers to all tobacco products that are used without burning. This includes products that are chewed or held in the mouth (dipped against the cheek or placed behind the lip) and fine powders inhaled nasally.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's 2019 National Health Interview Survey, 2.4% of US adults—equivalent to approximately 5.9 million people—reported using smokeless tobacco (eg, chewing tobacco, snuff, dip, snus, or dissolvables). Smokeless tobacco was used more commonly by men and was included among the noncombustible tobacco products used by US adults. As smokeless tobacco is placed intraorally, these compounds can lead to dysplastic changes in the oral mucosa, resulting in various white and red lesions. Smokeless tobacco use has been linked to the development of keratosis, leukoplakia, erythroplakia, verrucous carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. This acrivity reviews the oral mucosal lesions associated with smokeless tobacco use, focusing on their clinical presentation and potential for malignant transformation.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

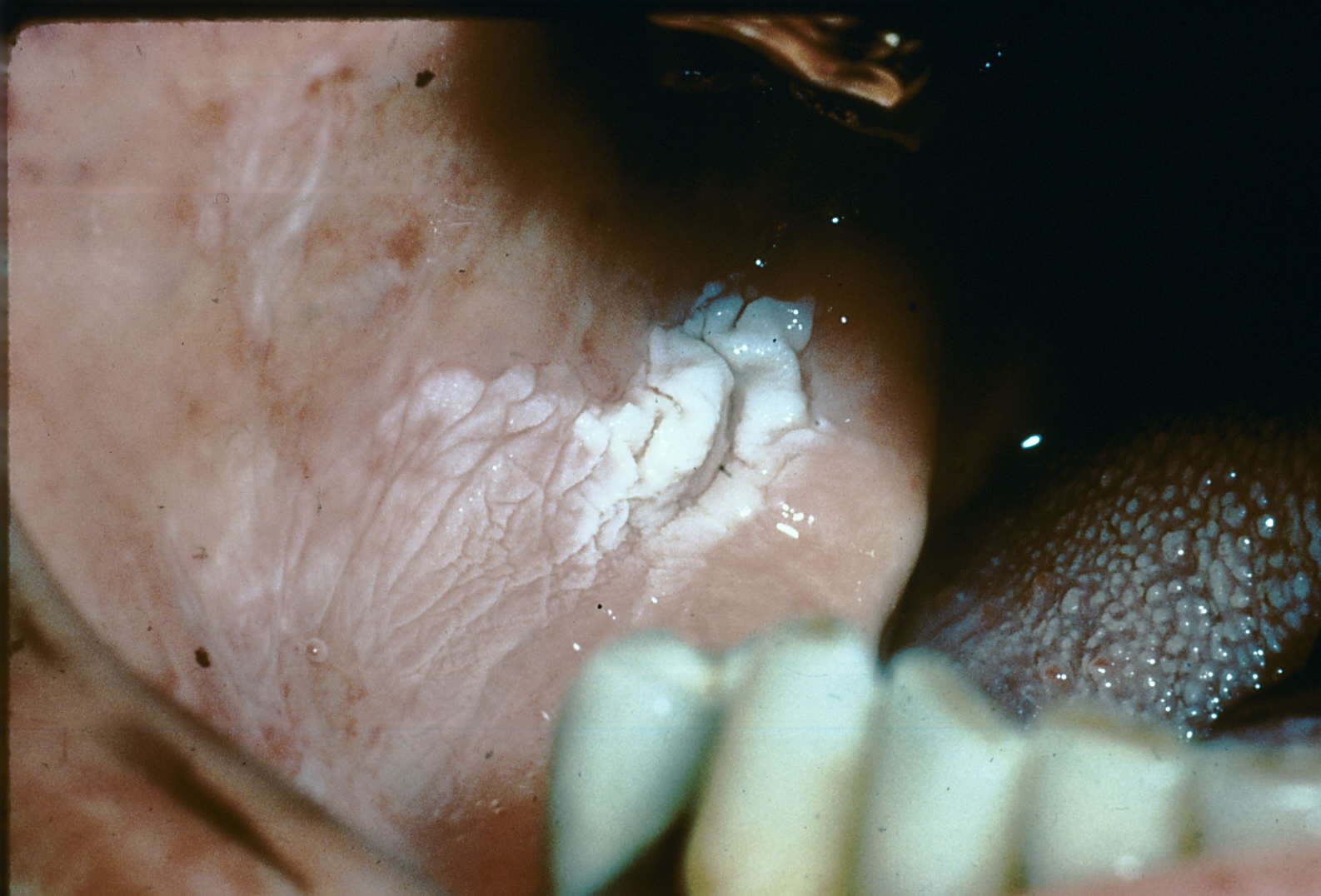

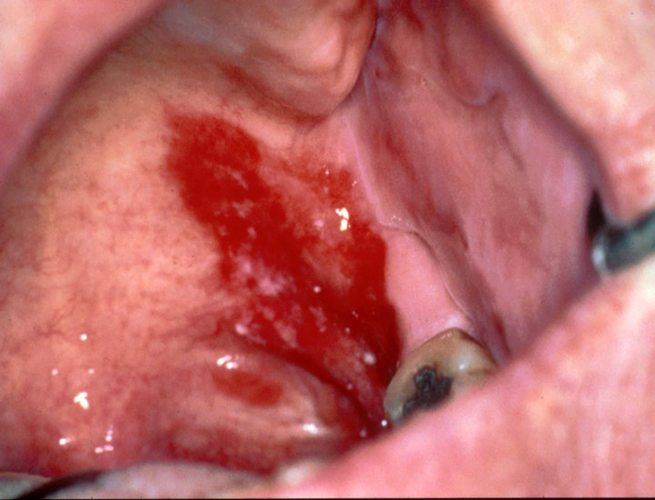

Smokeless tobacco keratosis is caused by constant frictional irritation of smokeless tobacco against the oral mucosa (see Image. Buccal Vestibule with Hyperkeratosis).[4] The formation rate depends on the frequency of habit, dose, and even the brand used. Leukoplakia has multiple etiologic agents, including tobacco, alcohol, betel nut/sanguinaria, ultraviolet radiation, microorganisms, and/or trauma (see Image. Leukoplakia on the Mouth Floor).[5] Erythroplakia is strongly associated with tobacco and alcohol consumption, with some correlations associated with betel quid chewing (see Image. Erythrolakia, Posterior Aspect of the Mouth).[6][7]

Verrucous carcinoma is a low-grade variant of squamous cell carcinoma (see Image. Buccal Vestibule With Hyperkeratosis and Verrucous Carcinoma). While its etiology is not clearly defined, human papillomavirus, smoking, poor oral hygiene, lichenoid lesions, or chewing tobacco have been attributed to its causation.[8] Squamous cell carcinoma has a variety of etiologies, with smoking and alcohol consumption regarded as significant risk factors. This is due to their synergistic effect in the development of malignancy and their associated usage in 90% of all reported cases.[9][10]

Epidemiology

Smokeless tobacco keratosis presents in 15% of chewing tobacco users and 60% of snuff users. Results from an epidemiological study by Rimal et al showed that smokeless tobacco keratosis was the most prevalent premalignant disorder found in 50.4% of their analyzed population.[11] Leukoplakia typically presents in patients older than 40, with an average age of presentation at 60. Leukoplakia is an uncommon disease process in young patients.[12] Approximately 70% of these lesions are found on the vermilion border, buccal mucosa, or the gingiva.

Erythroplakia presents in roughly 0.02% to 0.83% of patients and is commonly seen in middle-aged and older adults.[6] Verrucous carcinoma presents an incidence of approximately 6% of all oral carcinomas.[13] These lesions have a predilection in men and typically present at a median age of 62 years.[14] Oral cancer is 2 to 3 times more prevalent in men compared to women in most ethnic groups.[10] Cancers of the head and neck represent nearly 700,000 of all diagnosed malignancies per year.[15] Of the annually diagnosed oral carcinomas, squamous cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 90% of rendered diagnoses.

Pathophysiology

Smokeless tobacco keratosis results from chronic irritation from the placement of smokeless tobacco, usually in the buccal vestibule. This irritation results in the deposition of excess fibrin-like material throughout the submucosa and an increase in keratin production, which results in the characteristic white corrugated appearance of the epithelium (eg, the mucosa) (see Image. Tongue, Lateral Border With Ulcerated Lesions). Leukoplakia and erythroplakia are clinically diagnostic terms. These lesions can result from multiple pathophysiological processes that result in their appearance.[16]

Verrucous carcinoma, a low-grade presentation of squamous cell carcinoma, has an increased keratin production, giving it a verrucous, wart-like appearance. In addition, the epithelium thickens (hyperplasia); however, very little dysplasia is seen within the epithelium. Squamous cell carcinoma develops due to dysplastic changes throughout the epithelium, disrupting the basement membrane and invasion into the connective tissue; these changes cause abnormal growth or atrophy of epithelial tissue.

Histopathology

Smokeless tobacco keratosis may present with a nonspecific appearance, with hyperkeratotic and/or acanthotic squamous epithelium. Intracellular edema and increased subepithelial vascularity may also be noted. Parakeratin chevrons above or within the superficial epithelial layers can generally be visualized. Therefore, histologic examination of these lesions should evaluate for epithelial dysplasia.

Leukoplakia presents with hyperkeratosis, a thickened keratin layer, possible acanthosis, and a thickened spinous layer. Notably, diagnosing leukoplakia is a clinical term only, and a biopsy is required to determine a definitive diagnosis. The biopsy should be collected from the most severe site. Over 90% of erythroplakia lesions present histopathologically with epithelial dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Keratin is typically not produced, and epithelium atrophy is generally noted.

Verrucous carcinomas have a deceptively benign histopathologic presentation. These lesions exhibit wide, elongated rete pegs that push into underlying connective tissue and have abundant parakeratin clefts between surface projections. The epithelial cells are not generally dysplastic; however, an intense inflammatory infiltrate will likely be noted in the submucosa.[17] Squamous cell carcinoma arises from the dysplastic epithelium. Histologically, it presents as cords or islands of malignant epithelial cells penetrating/invading through the basement membrane into the submucosa below. In addition, severe inflammatory cell infiltrates within the submucosa are often noted in response to the invasion.

History and Physical

Smokeless tobacco keratosis presents as a characteristic white corrugated plaque on the oral mucosa where the tobacco is placed. Early lesions present as a white film that, over time, becomes more keratotic with distinct pouching.[4] Leukoplakia is a white patch or plaque that cannot be characterized clinically or pathologically as any other disease. These lesions get their color from the thickened keratin or spinous layer.

Erythroplakia is a red patch or plaque that cannot be clinically diagnosed as any other condition. Commonly, these lesions are well-demarcated, erythematous, asymptomatic patches with a velvety texture. At times, lesions may display a combination of erythroplakia and leukoplakia, which are then termed erytholeukoplakia. While less common than leukoplakia, erythroplakia and erytholeukoplakia have a higher malignant potential, with most biopsied cases exhibiting dysplasia or carcinoma in situ.[18][19] Common sites are the floor of the mouth, tongue, and soft palate.

Verrucous carcinoma presents as a diffuse, well-demarcated, painless plaque with papillary or verruciform projections. These lesions are typically white but can appear pink depending on the amount of keratin production and the increase in the underlying vasculature. Verrucous carcinomas typically present on the mandibular vestibule, buccal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, and hard palate. When associated with smokeless tobacco use, it typically corresponds to the location of chronic tobacco placement. Squamous cell carcinoma can have a variety of presentations. Generally, the hallmark presentation is deep ulceration with rolled borders in a high-risk area, such as the tongue's posterior-lateral aspect or the mouth's floor.

Evaluation

Smokeless tobacco keratosis can be diagnosed through clinical examination and patient interviews. If a corrugated buccal mucosa is noted, the patient should be questioned regarding the use of smokeless tobacco. In addition, the clinician should determine if the location where the patient places the tobacco correlates with the lesion identified. Leukoplakia should be evaluated closely, as more than 33% of oral carcinomas exhibit leukoplakia before becoming a true malignancy. As a clinical diagnostic term, an effort to identify any clinical source or cause of the lesion should be explored.[20]

Erythroplakia may present similarly to other lesions, ranging from benign to malignant. The red color is due to atrophy of the epithelium, which exposes the microvasculature of the underlying tissue. These lesions should be biopsied after ruling out all clinically possible causes to determine whether epithelial dysplasia or malignancy is present.

Verrucous carcinoma should be evaluated closely, as it is a low-grade variant of squamous cell carcinoma and may be easily overlooked and/or misdiagnosed.[21] With varied clinical presentations, squamous cell carcinoma should be evaluated closely. In addition, patients must be interviewed in-depth about their habits to determine if they are at high risk for developing oral cancer.[22]

Treatment / Management

Smokeless tobacco keratosis will typically self-resolve with cessation of the habit. Patients may be counseled initially on switching the location of tobacco placement and then followed up for evaluation of the area 2 weeks later. In this time frame, early to moderately developed lesions should self-resolve, with more advanced lesions either requiring more time to resolve or should be considered potentially malignant. The clinician should counsel the patient on smoking cessation, as switching sides could introduce a risk of dysplastic changes in other sites within the mouth.

Leukoplakia should be treated as a precancerous or premalignant lesion, as the frequency of transformation into a malignancy is greater than that of normal, unaltered mucosa. Treatment of erythroplakia is guided by histopathological diagnosis. If any evidence of dysplasia is noted, complete surgical excision and close clinical follow-up are warranted, as recurrence and multifocal involvement are common.[7] One in 5 verrucous carcinomas will develop into squamous cell carcinoma, so early treatment is paramount.(B2)

The treatment of choice for these lesions is surgical excision with clear margins (normal tissue) to reduce the chance of recurrence. Squamous cell carcinoma should be excised entirely to achieve clear margins and reduce the potential for recurrence. In addition, patients should be counseled on their high-risk behaviors to aid in reducing their risk of recurrence or the development of a new primary lesion.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes the following:

Smokeless Tobacco Keratosis

- Frictional keratosis

- Leukoplakia

- Squamous cell carcinoma

Leukoplakia

- Leukoedema

- Linea alba

- Morsicatio buccarum/linguarum

- Squamous cell carcinoma

Erythroplakia

- Mucositis

- Candidiasis

- Psoriasis

- Vascular lesions

- Squamous cell carcinoma

Verrucous Carcinoma

- Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia

- Verruca vulgaris

- Squamous papilloma

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- Erythroleukoplakia

- Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia

- Oral manifestation of deep fungal infection

Prognosis

Smokeless tobacco keratosis has a guarded but good prognosis; however, the resolution is highly patient-dependent. More advanced lesions may require biopsy and further monitoring for potential malignant changes. Leukoplakia has a guarded prognosis, as the term is a strictly clinical diagnosis. Since premalignancy has potential, these lesions should be considered precancerous until an otherwise benign diagnosis is rendered.[23] Erythroplakic lesions have a guarded prognosis, as most present with some form of epithelial dysplasia.[24]

Verrucous carcinoma, like a low-grade variant of squamous cell carcinoma, has a guarded prognosis. Surgical excision typically eliminates the lesion itself; however, there is a high potential for recurrence without cessation of high-risk behaviors. Squamous cell carcinoma has a poor prognosis despite therapeutic advances in treatment.[10] The key to increasing this condition's survivability is identifying and eliminating risk factors, early diagnosis, and treatment. Oral cancers have a 5-year survival rate of approximately 50%.[23]

Complications

Smokeless tobacco keratosis is the direct result of a habit. Consequently, if a patient is not willing to cease or even reduce their use of smokeless tobacco, the lesion will not resolve. Therefore, patients should be appropriately counseled. Leukoplakia and erythroplakia are clinical diagnoses and require biopsy for a definitive diagnosis. Verrucous and squamous cell carcinoma are malignant processes that should be treated promptly to improve the patient’s quality of life. Depending on the staging, patients may undergo extensive surgical interventions followed by chemotherapy and/or radiation, which will significantly impact their quality of life.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Smokeless tobacco use places patients at high risk for the development of all the lesions discussed and can be prevented by discontinuing use. Patients should be informed on the risks of the continuation of their habit, as well as directed to tobacco cessation programs to improve both oral and systemic health.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Smokeless tobacco use can result in a variety of different pathological processes. Therefore, each clinician who sees patients who use tobacco products should counsel them on the risks of their habit and encourage cessation. If lesions that appear suspicious in the oral cavity are noted, an appropriate referral for evaluation and diagnosis should be made to an oral healthcare clinician.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Buccal Vestibule With Hyperkeratosis and Verrucous Carcinoma. Verrucous carcinoma is a low-grade variant of squamous cell carcinoma. While its etiology is not clearly defined, human papillomavirus, smoking, poor oral hygiene, lichenoid lesions, or chewing tobacco have been attributed to its causation.

Contributed by H Olmo, DDS, MS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Cornelius ME, Wang TW, Jamal A, Loretan CG, Neff LJ. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2019. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2020 Nov 20:69(46):1736-1742. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6946a4. Epub 2020 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 33211681]

Zakiyah N, Purwadi FV, Insani WN, Abdulah R, Puspitasari IM, Barliana MI, Lesmana R, Amaliya A, Suwantika AA. Effectiveness and Safety Profile of Alternative Tobacco and Nicotine Products for Smoking Reduction and Cessation: A Systematic Review. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2021:14():1955-1975. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S319727. Epub 2021 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 34326646]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHecht SS, Hatsukami DK. Smokeless tobacco and cigarette smoking: chemical mechanisms and cancer prevention. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2022 Mar:22(3):143-155. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00423-4. Epub 2022 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 34980891]

Müller S. Frictional Keratosis, Contact Keratosis and Smokeless Tobacco Keratosis: Features of Reactive White Lesions of the Oral Mucosa. Head and neck pathology. 2019 Mar:13(1):16-24. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0986-3. Epub 2019 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 30671762]

Sciubba JJ. Oral leukoplakia. Critical reviews in oral biology and medicine : an official publication of the American Association of Oral Biologists. 1995:6(2):147-60 [PubMed PMID: 7548621]

Reichart PA, Philipsen HP. Oral erythroplakia--a review. Oral oncology. 2005 Jul:41(6):551-61 [PubMed PMID: 15975518]

Duan SM, Liu TN, Zeng X. [Research progress of oral erythroplakia]. Zhonghua kou qiang yi xue za zhi = Zhonghua kouqiang yixue zazhi = Chinese journal of stomatology. 2020 Jun 9:55(6):421-424. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112144-20190923-00360. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32486574]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDuncan S, Finegersh A, Orosco RK, Wu N, Brumund KT, Califano JA, Coffey CS, Moss WJ. Clinicopathologic Features of Oral Verrucous Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2025 Mar:134(3):187-194. doi: 10.1177/00034894241298378. Epub 2024 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 39529216]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKoontongkaew S. The tumor microenvironment contribution to development, growth, invasion and metastasis of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Journal of Cancer. 2013:4(1):66-83. doi: 10.7150/jca.5112. Epub 2013 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 23386906]

Rivera C. Essentials of oral cancer. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2015:8(9):11884-94 [PubMed PMID: 26617944]

Rimal J, Shrestha A, Maharjan IK, Shrestha S, Shah P. Risk Assessment of Smokeless Tobacco among Oral Precancer and Cancer Patients in Eastern Developmental Region of Nepal. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP. 2019 Feb 26:20(2):411-415 [PubMed PMID: 30803200]

Soares AC, Gomes APN, Calderipe CB, Salum FG, Cherubini K, Martins MD, Schuch LF, Kirschnick LB, Abreu LG, Santos-Silva AR, Vasconcelos ACU. Oral leukoplakia and erythroplakia in young patients: a southern Brazilian multicenter study. Brazilian oral research. 2024:38():e069. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2024.vol38.0069. Epub 2024 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 39109766]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIlie IO, Mărgăritescu OC, Stepan AE, Ciurea RN, Florescu MM, Munteanu C, Şerbănescu MS, Mărgăritescu C. Epidemiological and Histopathological Features of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma-A Retrospective Study. Current health sciences journal. 2024 Jul-Sep:50(3):411-420. doi: 10.12865/CHSJ.50.03.08. Epub 2024 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 39574818]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWang N, Huang M, Lv H. Head and neck verrucous carcinoma: A population-based analysis of incidence, treatment, and prognosis. Medicine. 2020 Jan:99(2):e18660. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018660. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31914052]

Cohen EEW, Bell RB, Bifulco CB, Burtness B, Gillison ML, Harrington KJ, Le QT, Lee NY, Leidner R, Lewis RL, Licitra L, Mehanna H, Mell LK, Raben A, Sikora AG, Uppaluri R, Whitworth F, Zandberg DP, Ferris RL. The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer consensus statement on immunotherapy for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (HNSCC). Journal for immunotherapy of cancer. 2019 Jul 15:7(1):184. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0662-5. Epub 2019 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 31307547]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMahapatra M, Tripathi KP, Bhadouria TS, Rai S, Malik A, Murali S, Tiwari HD. Incidence Progression and Epidemiological Study of Oral Precancerous Lesions: An Original Research. Journal of pharmacy & bioallied sciences. 2025 May:17(Suppl 1):S451-S453. doi: 10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_1419_24. Epub 2025 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 40510950]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSonalika WG, Anand T. Oral verrucous carcinoma: A retrospective analysis for clinicopathologic features. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics. 2016 Jan-Mar:12(1):142-5. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.172709. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27072227]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYang SW, Lee YS, Chang LC, Hsieh TY, Chen TA. Outcome of excision of oral erythroplakia. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2015 Feb:53(2):142-7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2014.10.016. Epub 2014 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 25467247]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCarlson ER, Kademani D, Ward BB, Oreadi D. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon's Position Paper on Oral Mucosal Dysplasia. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2023 Aug:81(8):1042-1054. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2023.04.017. Epub 2023 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 37244288]

Alabdulaaly L, Almazyad A, Woo SB. Gingival Leukoplakia: Hyperkeratosis with Epithelial Atrophy Is A Frequent Histopathologic Finding. Head and neck pathology. 2021 Dec:15(4):1235-1245. doi: 10.1007/s12105-021-01333-5. Epub 2021 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 34057694]

Ghosh S, Rao RS, Upadhyay MK, Kumari K, Sanketh DS, Raj AT, Parveen S, Alhazmi YA, Jethlia A, Mushtaq S, Sarode S, Reda R, Patil S, Testarelli L. Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia Revisited: A Retrospective Clinicopathological Study. Clinics and practice. 2021 Jun 1:11(2):337-346. doi: 10.3390/clinpract11020048. Epub 2021 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 34205902]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePanta P, Dhopathi SR, Gilligan G, Seshadri M. Invasive oral squamous cell carcinoma induced by concurrent smokeless tobacco and creamy snuff use: A case report. Oral oncology. 2021 Jul:118():105354. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2021.105354. Epub 2021 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 34023217]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu W, Shi LJ, Wu L, Feng JQ, Yang X, Li J, Zhou ZT, Zhang CP. Oral cancer development in patients with leukoplakia--clinicopathological factors affecting outcome. PloS one. 2012:7(4):e34773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034773. Epub 2012 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 22514665]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNeville BW, Day TA. Oral cancer and precancerous lesions. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2002 Jul-Aug:52(4):195-215 [PubMed PMID: 12139232]