Introduction

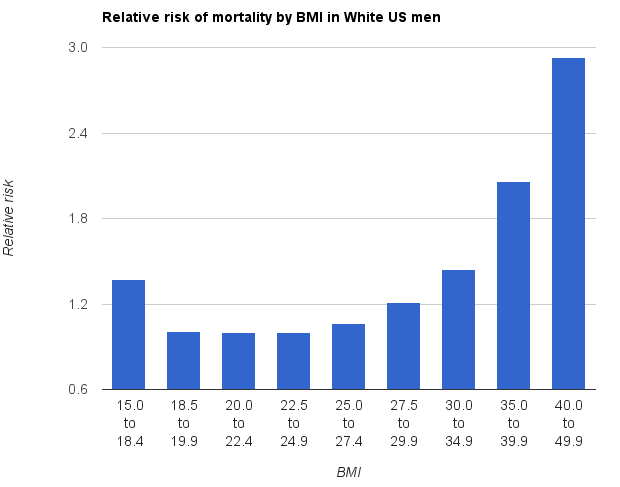

Obesity constitutes a major public health concern around the globe, with serious medical, economic, and social consequences. The condition is associated with elevated risks of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, osteoarthritis, and all-cause mortality (see Image. Relative Mortality Risk by Body Mass Index).[1][2] The World Health Organization identifies obesity as having a body mass index of or more than 30 kg/m², with recent data showing increasing prevalence. In the U.S., adult obesity increased from 30.5% during the years 1999 to 2000 to 42.4% in 2017 to 2018.

The global burden of obesity has escalated markedly. A pooled analysis of 1,698 population-based studies encompassing 19.2 million adults found that worldwide obesity prevalence more than doubled between 1975 and 2014.[3] High-income countries experienced particularly steep increases, although low- and middle-income countries are also increasingly affected.

While obesity is multifactorial, a primary driver is an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure. Weight management involves more than calories in versus calories out. Dietary quality also plays a critical role. Plant-based diets, in particular, may support weight loss by enhancing satiety and regulating hormones.[4] Additional contributors include physical inactivity, consumption of ultra-processed foods, sleep deprivation, psychological stress, and socioeconomic factors. Genetics, microbiome composition, and neuroendocrine feedback loops further modulate individual susceptibility to weight gain. Therefore, strategies for obesity prevention and treatment must be multifaceted and personalized, with emphasis on long-term behavioral and environmental interventions.

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

Physiology of Weight Loss and Weight Loss Maintenance

Sustained weight loss is a biologically complex process, driven by coordinated physiological adaptations that promote energy conservation and increase appetite, making long-term maintenance particularly challenging. These changes include metabolic adjustment and energy balance, hormonal regulation of appetite, hypothalamic–neuroendocrine responses, dynamics of energy expenditure, and behavioral and psychological factors.

Metabolic adaptation and energy balance

Weight loss triggers physiological adaptations that resist further loss and promote regain. Resting metabolic rate (RMR) decreases more than expected for the new body composition—a phenomenon known as metabolic adaptation. This effect persists during weight maintenance and results from reduced thyroid hormone levels, changes in mitochondrial efficiency, and decreased energy expenditure during physical activity. Notably, in the "The Biggest Loser" cohort, metabolic adaptation persisted at -499 kcal/day even 6 years after weight loss.[5]

Hormonal regulation of appetite

After weight loss, circulating levels of leptin, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), peptide YY, and cholecystokinin decrease, while ghrelin levels increase, leading to heightened hunger and reduced satiety. These hormonal shifts produce an approximate increase in appetite of 100 kcal/day for each kilogram lost, outweighing the concurrent decrease in energy expenditure.[6]

Hypothalamic and neuroendocrine responses

Neuroendocrine mechanisms shift after weight loss. Activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis elevates cortisol levels, promoting fat storage and increased appetite. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and triiodothyronine levels decline, lowering RMR. Additionally, reduced sympathetic nervous system activity diminishes thermogenesis.[7][8]

Energy expenditure dynamics

The body further adjusts by reducing nonexercise activity thermogenesis and enhancing mitochondrial efficiency, lowering the energy cost per movement. In humans undergoing calorie restriction, resting energy expenditure decreases by approximately 100 kcal/day, with mitochondrial effects confirmed in skeletal muscle.[9]

Behavioral and Psychological Factors

Behavioral and psychological factors strongly influence weight loss and maintenance. Appetite dysregulation represents a key challenge. Diets that promote greater satiety have been associated with approximately 3.6 kg more weight loss, highlighting hunger control as an essential strategy.[10] Emotional eating also contributes to weight management difficulties. A meta-analysis of 11 studies (n = 7,207) found that individuals with obesity scored significantly higher on measures of emotional eating compared to healthy-weight peers.[11]

Self-monitoring presents additional challenges. The effectiveness of frequent self-weighing remains somewhat controversial. A systematic review of 20 studies reported that frequent self-weighing can negatively affect mood, self-esteem, and body image in women and younger adults. Conversely, a meta-analysis found that weight loss programs incorporating participant accountability through self-weighing achieved greater success than control groups.[12] Integrating psychological support alongside monitoring further improved outcomes.[13]

Table 1 summarizes the key physiological adaptations that counteract weight loss and promote weight regain. The table also outlines the mechanisms and effects of these adaptations on long-term weight maintenance.

Table 1. Summary of Physiological Adaptations That Promote Weight Regain Following Weight Loss

|

Adaptation Type |

Mechanism |

Effect on Weight Maintenance |

|

Metabolic responses |

RMR decreases beyond what is expected for the new body size |

Promotes weight regain despite calorie control [14] |

|

Hormonal changes |

Leptin, GLP-1, and peptide YY decrease, while ghrelin increases |

Increases hunger and reduces satiety |

|

Neuroendocrine shifts |

Triiodothyronine and sympathetic nervous system activity decrease, while cortisol increases |

Encourages fat storage and energy conservation |

|

Energy efficiency |

Mitochondrial efficiency increases, and nonexercise activity thermogenesis decreases |

Lowers total daily energy expenditure [15] |

Issues of Concern

Energy expenditure associated with physical activity decreases as people lose weight and improve cardiovascular fitness. Consequently, both caloric intake and activity levels must be continually adjusted to prevent weight regain.[16]

However, many individuals struggle to adhere to intensive diet and physical activity programs, particularly when expectations are unrealistic or routines are unsustainable. This difficulty frequently leads to frustration and eventual discontinuation of efforts. Managing patient expectations and emphasizing realistic, motivational, and personalized goals is essential to support long-term adherence. For patients with comorbidities or physical limitations, incorporating alternative forms of physical activity, such as nonweight-bearing aerobic exercises or resistance training, is critical, underscoring the importance of considering patient preferences and capabilities in counseling.[17]

Additionally, psychological factors play a critical role in weight loss maintenance, as mood and eating disorders can significantly impair the ability to sustain weight reduction. Referring patients to behavioral health specialists is essential for long-term success. Although self-monitoring of weight, diet, and physical activity can be beneficial, recent studies indicate that frequent self-weighing may have negative psychological effects for some individuals. These findings underscore the importance of balancing the benefits and drawbacks of self-monitoring and involving behavioral health professionals when necessary.[18][19]

Clinical Significance

Successful long-term weight loss maintenance requires sustained changes in physical activity, diet, behavior, and psychological resilience. Strategies must specifically target biological adaptations that otherwise promote weight regain.

High-Volume Physical Activity

Engaging in high volumes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is a strong predictor of long-term success. Observational studies and clinical trials consistently demonstrate that individuals maintaining at least 250 minutes of physical activity per week are significantly more likely to sustain weight loss. This level of activity counteracts the persistent decline in RMR and helps preserve lean body mass. Resistance training may also support weight maintenance. However, a systematic review found that aerobic training produced greater weight loss than resistance training in programs lasting at least 10 weeks, highlighting the particular value of aerobic exercise as an adjunct to diet and other measures.[20]

Nutrition Strategies for Weight Maintenance

Diets high in protein and low in energy density enhance satiety, increase thermogenesis, and support lean mass retention. Protein typically promotes greater satiety than carbohydrates or fat, increases diet-induced thermogenesis, and helps preserve lean muscle mass during weight loss.[21]

Increasing the intake of vegetables, whole grains, and legumes helps reduce caloric intake without increasing hunger. Strategically incorporating low-energy-density foods promotes satiety and supports long-term weight control, as demonstrated in both randomized and observational studies.[22]

Appetite Hormone Regulation and Pharmacotherapy

Persistent hormonal adaptations following weight loss include decreased leptin and increased ghrelin levels, which heighten hunger and reduce satiety.[23] These hormonal changes can undermine efforts to maintain a reduced weight. GLP-1 receptor agonists have shown promise in mitigating these effects. A 2024 randomized trial demonstrated that combining GLP-1 receptor agonists with structured exercise resulted in approximately 6 kg greater weight loss, which was maintained after medication cessation, compared with GLP-1 therapy alone.

Behavioral Self-Regulation

Ongoing self-monitoring, including regular weighing, food logging, and tracking physical activity, is strongly associated with improved weight maintenance outcomes. Data from the National Weight Control Registry and a 2011 systematic review indicate that consistent self-monitoring enhances awareness and facilitates early detection of potential weight regain.[24][25]

Structured Support and Coaching

Professional and peer support enhance motivation and problem-solving skills. A 12-month randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated that individuals with suboptimal early weight loss who received extended telephone coaching achieved significantly greater weight loss at 12 months compared with controls.[26] Programs incorporating behavioral goal-setting, ongoing feedback, and regular contact generally produce more sustainable outcomes.

Addressing Psychological Barriers

Emotional eating, stress, and psychological comorbidities often impede long-term weight loss maintenance. Emotional eating is notably more prevalent among individuals with overweight or obesity and is associated with poorer dietary quality. Identifying and addressing these barriers through counseling, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or mindfulness-based interventions represents a critical component of comprehensive weight maintenance strategies.

Table 2 summarizes evidence-based interventions that support long-term weight loss maintenance. The table highlights the mechanism of each strategy, relevant citations, and the quality of evidence, providing clinicians with guidance on effective approaches to sustain weight reduction and promote patient adherence. The grade or strength of evidence is indicated, considering study design and consistency of results.

Table 2. Summary of Weight Loss Maintenance Strategies

|

Number |

Intervention |

Mechanism |

Citation |

Grade of Evidence |

|

1 |

High-volume physical activity |

At least 150 min/wk of aerobic exercise supports weight maintenance. Greater duration and intensity produce dose-dependent reductions in weight and fat. |

Jayedi A et al [27] |

High: Robust meta-analysis of 109 RCTs demonstrating clear dose–response effects |

|

2 |

Dietary quality and pattern |

Whole-food, plant-based, low-energy-density diets increase satiety and support long-term adherence. |

Tran et al [28] |

High: Systematic review of RCTs and cohort studies |

|

3 |

Behavioral self-regulation |

Self-monitoring, goal-setting, and habit reinforcement promote sustained behavior change and prevent relapse. |

Burke LE et al |

Moderate: Systematic review of RCTs and prospective cohorts |

|

4 |

Structured support and coaching |

Provides accountability, motivation, and individualized problem-solving to enhance weight maintenance. |

Leahey TM et al [29] |

Moderate: RCT demonstrating meaningful maintenance effect |

|

5 |

Addressing psychological barriers |

Managing emotional eating, stress, and psychological comorbidities supports sustained lifestyle changes. |

Varkevisser RDM et al |

High: Comprehensive systematic review with meta-analysis |

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A coordinated, interprofessional approach is essential for supporting long-term weight loss maintenance in patients with obesity, particularly those with comorbidities. Collaboration among physicians, registered dietitians, behavioral specialists, and exercise professionals enhances adherence and improves outcomes.

For instance, a real-world, team-based obesity treatment program, including a physician, dietitian, nurse, and exercise physiologist, achieved significantly greater weight loss maintenance over 24 months compared with usual care.[30] Expert involvement from behavioral health professionals is particularly valuable for addressing emotional eating, binge eating, and body-image concerns. A systematic review and meta-analysis of motivational interviewing in adults with overweight or obesity reported a standardized mean weight loss of -0.51 kg/m², corresponding to approximately 1.5 kg reduction compared with control groups.[31]

Referral to a bariatric surgery team may be appropriate when lifestyle interventions fail to achieve meaningful weight loss, rather than for weight loss maintenance alone. The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society's 2022 guidelines for bariatric surgery recommend comprehensive, evidence-based preoperative and postoperative protocols to optimize surgical outcomes.[32]

Exercise professionals, including lifestyle coaches, trainers, and physical therapists, develop individualized activity plans that accommodate mobility limitations and minimize injury risk, enhancing adherence in patients with functional impairments. The American College of Sports Medicine recommends 250 to 300 min/wk of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise to support long-term weight loss maintenance.[33]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Physical activity effectively promotes weight loss maintenance in patients with obesity or overweight.[20] Maintaining patient adherence and commitment to physical activity programs alongside calorie-restriction interventions benefits from consistent guidance from an interprofessional healthcare team. Such support helps prevent unrealistic patient expectations and the resulting frustration and discontinuation of efforts. A coordinated, interprofessional approach provides patients with sustained support to maintain weight loss.[34]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Nurses and allied health professionals, including dietitians, physical therapists, and psychologists, provide personalized care, education, and ongoing patient support. The involvement of these professionals in comprehensive assessment, regular monitoring, and behavioral counseling has been shown to improve adherence and outcomes in weight management programs significantly. Interprofessional collaboration, where nurses, allied health professionals, and medical providers work together, enhances the effectiveness of interventions by combining expertise across disciplines. This approach fosters more individualized and sustainable treatment plans. Clinical evidence demonstrates that team-based care improves both weight loss and maintenance while addressing the psychological and behavioral complexities of obesity.[35]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Relative Mortality Risk by Body Mass Index. The graph shows the relative risk of mortality in White men in the United States who never smoked; it demonstrates increased risk at higher body mass index categories.

James Heilman, MD, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC public health. 2009 Mar 25:9():88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-88. Epub 2009 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 19320986]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBerrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, Flint AJ, Hannan L, MacInnis RJ, Moore SC, Tobias GS, Anton-Culver H, Freeman LB, Beeson WL, Clipp SL, English DR, Folsom AR, Freedman DM, Giles G, Hakansson N, Henderson KD, Hoffman-Bolton J, Hoppin JA, Koenig KL, Lee IM, Linet MS, Park Y, Pocobelli G, Schatzkin A, Sesso HD, Weiderpass E, Willcox BJ, Wolk A, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Willett WC, Thun MJ. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Dec 2:363(23):2211-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000367. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21121834]

Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS data brief. 2020 Feb:(360):1-8 [PubMed PMID: 32487284]

Klementova M, Thieme L, Haluzik M, Pavlovicova R, Hill M, Pelikanova T, Kahleova H. A Plant-Based Meal Increases Gastrointestinal Hormones and Satiety More Than an Energy- and Macronutrient-Matched Processed-Meat Meal in T2D, Obese, and Healthy Men: A Three-Group Randomized Crossover Study. Nutrients. 2019 Jan 12:11(1):. doi: 10.3390/nu11010157. Epub 2019 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 30642053]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFothergill E, Guo J, Howard L, Kerns JC, Knuth ND, Brychta R, Chen KY, Skarulis MC, Walter M, Walter PJ, Hall KD. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after "The Biggest Loser" competition. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.). 2016 Aug:24(8):1612-9. doi: 10.1002/oby.21538. Epub 2016 May 2 [PubMed PMID: 27136388]

Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, Purcell K, Shulkes A, Kriketos A, Proietto J. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Oct 27:365(17):1597-604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105816. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22029981]

Valassi E, Scacchi M, Cavagnini F. Neuroendocrine control of food intake. Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases : NMCD. 2008 Feb:18(2):158-68 [PubMed PMID: 18061414]

Kalra SP, Kalra PS. Neuroendocrine control of energy homeostasis: update on new insights. Progress in brain research. 2010:181():17-33. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)81002-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20478430]

Rosenbaum M, Vandenborne K, Goldsmith R, Simoneau JA, Heymsfield S, Joanisse DR, Hirsch J, Murphy E, Matthews D, Segal KR, Leibel RL. Effects of experimental weight perturbation on skeletal muscle work efficiency in human subjects. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2003 Jul:285(1):R183-92 [PubMed PMID: 12609816]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHansen TT, Andersen SV, Astrup A, Blundell J, Sjödin A. Is reducing appetite beneficial for body weight management in the context of overweight and obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis from clinical trials assessing body weight management after exposure to satiety enhancing and/or hunger reducing products. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2019 Jul:20(7):983-997. doi: 10.1111/obr.12854. Epub 2019 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 30945414]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVasileiou V, Abbott S. Emotional eating among adults with healthy weight, overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics : the official journal of the British Dietetic Association. 2023 Oct:36(5):1922-1930. doi: 10.1111/jhn.13176. Epub 2023 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 37012653]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMadigan CD, Daley AJ, Lewis AL, Aveyard P, Jolly K. Is self-weighing an effective tool for weight loss: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2015 Aug 21:12():104. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0267-4. Epub 2015 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 26293454]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePacanowski CR, Linde JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Self-Weighing: Helpful or Harmful for Psychological Well-Being? A Review of the Literature. Current obesity reports. 2015 Mar:4(1):65-72. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0142-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26627092]

Hall KD, Kahan S. Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. The Medical clinics of North America. 2018 Jan:102(1):183-197. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29156185]

Jensen SBK, Blond MB, Sandsdal RM, Olsen LM, Juhl CR, Lundgren JR, Janus C, Stallknecht BM, Holst JJ, Madsbad S, Torekov SS. Healthy weight loss maintenance with exercise, GLP-1 receptor agonist, or both combined followed by one year without treatment: a post-treatment analysis of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2024 Mar:69():102475. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102475. Epub 2024 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 38544798]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFalkenhain K, Martin CK, Ravussin E, Redman LM. Energy expenditure, metabolic adaptation, physical activity and energy intake following weight loss: comparison between bariatric surgery and low-calorie diet. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2024 Oct 30:():. doi: 10.1038/s41430-024-01523-8. Epub 2024 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 39478234]

Khomkham P, Kaewmanee P. Patient motivation: A concept analysis. Belitung nursing journal. 2024:10(5):490-497. doi: 10.33546/bnj.3529. Epub 2024 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 39416359]

Caldwell AE, More KR, Chui TK, Sayer RD. Psychometric validation of four-item exercise identity and healthy-eater identity scales and applications in weight loss maintenance. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2024 Feb 23:21(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s12966-024-01573-y. Epub 2024 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 38395833]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVarkevisser RDM, van Stralen MM, Kroeze W, Ket JCF, Steenhuis IHM. Determinants of weight loss maintenance: a systematic review. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2019 Feb:20(2):171-211. doi: 10.1111/obr.12772. Epub 2018 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 30324651]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLafontant K, Rukstela A, Hanson A, Chan J, Alsayed Y, Ayers-Creech WA, Bale C, Ohigashi Y, Solis J, Shelton G, Alur I, Resler C, Heath A, Ericksen S, Forbes SC, Campbell BI. Comparison of concurrent, resistance, or aerobic training on body fat loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 2025 Dec:22(1):2507949. doi: 10.1080/15502783.2025.2507949. Epub 2025 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 40405489]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePaddon-Jones D, Westman E, Mattes RD, Wolfe RR, Astrup A, Westerterp-Plantenga M. Protein, weight management, and satiety. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2008 May:87(5):1558S-1561S [PubMed PMID: 18469287]

Rolls BJ. Dietary energy density: Applying behavioural science to weight management. Nutrition bulletin. 2017 Sep:42(3):246-253. doi: 10.1111/nbu.12280. Epub 2017 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 29151813]

Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Nieuwenhuizen A, Tomé D, Soenen S, Westerterp KR. Dietary protein, weight loss, and weight maintenance. Annual review of nutrition. 2009:29():21-41. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-080508-141056. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19400750]

Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2005 Jul:82(1 Suppl):222S-225S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. Epub [PubMed PMID: 16002825]

Burke LE, Wang J, Sevick MA. Self-monitoring in weight loss: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2011 Jan:111(1):92-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21185970]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceUnick JL, Pellegrini CA, Dunsiger SI, Demos KE, Thomas JG, Bond DS, Lee RH, Webster J, Wing RR. An Adaptive Telephone Coaching Intervention for Patients in an Online Weight Loss Program: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA network open. 2024 Jun 3:7(6):e2414587. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.14587. Epub 2024 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 38848067]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJayedi A, Soltani S, Emadi A, Zargar MS, Najafi A. Aerobic Exercise and Weight Loss in Adults: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. JAMA network open. 2024 Dec 2:7(12):e2452185. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.52185. Epub 2024 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 39724371]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTran E, Dale HF, Jensen C, Lied GA. Effects of Plant-Based Diets on Weight Status: A Systematic Review. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity : targets and therapy. 2020:13():3433-3448. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S272802. Epub 2020 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 33061504]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLeahey TM, Gorin AA, Huedo-Medina TB, Denmat Z, Field C, Gilder C, Wyckoff EP, O'Connor K, Hahn K, Jenkins K, Unick JL, Hand G, McManus-Shipp K, Calcaterra J, Falk G. Patient-Delivered Continuous Care for Weight Loss Maintenance: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA internal medicine. 2025 Jul 1:185(7):767-776. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2025.1345. Epub [PubMed PMID: 40423949]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTapsell LC, Lonergan M, Batterham MJ, Neale EP, Martin A, Thorne R, Deane F, Peoples G. Effect of interdisciplinary care on weight loss: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ open. 2017 Jul 13:7(7):e014533. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014533. Epub 2017 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 28710205]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceArmstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, Sigal RJ, Campbell TS, Hemmelgarn BR. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2011 Sep:12(9):709-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00892.x. Epub 2011 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 21692966]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStenberg E, Dos Reis Falcão LF, O'Kane M, Liem R, Pournaras DJ, Salminen P, Urman RD, Wadhwa A, Gustafsson UO, Thorell A. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Bariatric Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations: A 2021 Update. World journal of surgery. 2022 Apr:46(4):729-751. doi: 10.1007/s00268-021-06394-9. Epub 2022 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 34984504]

Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK, American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2009 Feb:41(2):459-71. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19127177]

Herbozo S, Brown KL, Burke NL, LaRose JG. A Call to Reconceptualize Obesity Treatment in Service of Health Equity: Review of Evidence and Future Directions. Current obesity reports. 2023 Mar:12(1):24-35. doi: 10.1007/s13679-023-00493-5. Epub 2023 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 36729299]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGriffiths A, Brooks R, Haythorne R, Kelly G, Matu J, Brown T, Ahmed K, Hindle L, Ells L. The impact of Allied Health Professionals on the primary and secondary prevention of obesity in young children: A scoping review. Clinical obesity. 2023 Jun:13(3):e12571. doi: 10.1111/cob.12571. Epub 2022 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 36451267]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence